The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) 66-page report on its 2014 consultation with the U.S., pursuant to Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, repeats a number of long-standing, orthodox, and desirable policy recommendations that urge the U.S. to confront its many long-term fiscal and monetary challenges. This year’s report also contains an unprecedented number of audacious, highly politicized, and controversial proposals that appear to be an effort by the IMF to support the bulk of the Obama Administration’s statist economic policy agenda.

Overall, the latest IMF report is decidedly hostile to free enterprise. It promotes a heavy-handed, top-down approach to financial regulations, explicit taxpayer backing of financial sectors, and other expansions of the welfare state and big government—from recommending an increase in the U.S. minimum wage and adoption of “more proactive labor market policies” to a broad endorsement of Obamacare, a call for carbon taxes, and a recommended increase in the maximum taxable earnings for Social Security purposes.

A reasonable person studying the heretofore measured and circumspect reports conducted by the IMF about the U.S. economy during the past several decades (and, indeed, numerous contemporary IMF reports about other countries that exhibit similar restraint and sensitivity so as not to appear biased) could come to only one conclusion: The 2014 IMF analysis of the U.S. economy is the most starkly partisan in the long history of Article IV consultations.

Instead of meeting its statutory obligation to deliver difficult but necessary policy advice to a member country in deep financial straits by demanding immediate action by U.S. lawmakers to adopt structural entitlement reforms to control U.S. spending and debt growth, the IMF seems to be willingly following the Obama Administration’s federal budget playbook by urging immediate spending and tax increases—identifying for future action only a few very meek and ineffective suggestions for moderate entitlement tweaks.

Harvard economics professor Greg Mankiw has called the IMF’s faith that some forms of “expansionary” government spending (such as on infrastructure) will spur growth the “free-lunch view.” It might be “theoretically possible,” says Mankiw, but he is skeptical “about how often it will occur in practice.”[1]

In short, adoption of the IMF’s policy recommendations would not solve the problems confronting the U.S. They would, instead, inflict damaging tax increases, create a less stable financial system, introduce a whole host of new policy dilemmas, and put U.S. taxpayers at risk.

In this Backgrounder Heritage Foundation scholars analyze in detail the many areas where IMF economists get it wrong, and make recommendations to help them get back to fulfilling the original mandate of the IMF: to “facilitate the growth of international trade, thus promoting job creation, economic growth, and poverty reduction.”[2] Lacking that, Congress and the Obama Administration should assiduously avoid the IMF’s advice.

IMF Channels Obamanomics on U.S. Minimum Wage

The IMF report urges an increase in the U.S. minimum wage rate, claiming that an increase would raise incomes for millions of the so-called working poor.[3]

Ironically, a minimum-wage hike would have the opposite effect. As Heritage’s James Sherk testified last year, minimum wage laws often “hold back many of the workers its proponents want to help.”[4] Even worse, an Express Employments Professionals survey showed that “a whopping 38 percent of employers said that they would lay off employees if the proposed [minimum wage] hike went into effect.”[5]

Those layoffs would be toughest for young workers. Sherk reports that “the vast majority of minimum-wage workers are second (or third or fourth) earners in their family,” that many of them are between the ages of 16 and 24, and that most of them work part time. These entry-level positions are where they gain experience so they can quickly move up to higher-paying jobs.[6]

The IMF claim that the U.S. minimum wage is low “compared both to U.S. history and international standards”[7] is also wrong. In fact, as Heritage has reported, “Correctly adjusted for inflation, the minimum wage currently stands above its historical average since 1950.”[8]

Perhaps IMF analysts were not aware that more than 500 economists—including three Nobel laureates—have told Congress that President Obama’s proposal to raise the minimum wage would be a job killer.[9] In any case, by embracing major tenets of redistributive Obamanomics, the IMF has left no doubt that it has departed from the orthodox policy advice of fiscal discipline and market-oriented reforms it has heretofore given to countless developing countries.[10]

Congress and the Administration should ignore IMF calls for a higher minimum wage. Instead, they should take immediate steps to increase the productivity of America’s middle-class workers. Under President Obama, tax increases on individuals and businesses have held down wages because they have hindered worker productivity. After taxes, businesses have less money to invest in plants, equipment, and technology—which means that workers cannot be more productive. In addition, the President’s war on fossil fuels—oil, natural gas, and coal—is killing the creation of high-paid energy jobs.

Recommendation: In order to increase the wages of the average U.S. worker, Congress and the Administration should be cutting taxes and dramatically expanding U.S. drilling and mining capacity for hydrocarbons.

IMF Misses the Mark on U.S. Labor-Market Reforms

The IMF report emphasizes “raising productivity growth and labor force participation” as the first of five goals necessary to strengthen America’s economic recovery and improve its long-term outlook. Despite this correct diagnosis, the IMF then proceeds to offer the wrong solutions.

It is true that low labor-force participation is dragging down economic growth. The labor-force participation rate in the U.S. is lower today than it was in 1978, when significantly fewer women participated in the labor force.[11] Fewer people working means not only reduced economic output, but additional stress on the federal budget through reduced tax revenues, and wasted resources through government transfers.

The IMF’s prescription for this problem is to advocate “proactive labor market policies that lower long-term unemployment and raise participation.” While the IMF does not outline specific policies, “proactive” is usually code for more government intervention in the market, which would only translate to higher costs for employers and thus fewer jobs. High costs imposed by government are already impeding job creation.

According to the April 2014 survey by the National Federation of Independent Business, only 8 percent of small and independent businesses say it is a good time to expand facilities. They cite taxes and government red tape as their two biggest concerns.

Unlike the federal government, which effectively has access to an unlimited credit card, private businesses operate under budget constraints. If a business, for example, is required to pay workers 15 percent more, provide mandated benefits, or insure itself against costly litigation, it will have to cut some jobs. By contrast, Washington has become accustomed to passing on higher costs to future generations through a massive accumulation of debt.

Recommendation: There are many ways the U.S. government can help stimulate employment and workplace empowerment without burdening employers with higher costs or adding to the size and scope of the federal government. Some of these solutions are to:

- Reduce unnecessary and costly regulations;

- Reward work through lower taxes while minimizing disincentives to work through government transfers;

- Allow private businesses to make their own employment decisions;

- Learn from the successes of new, innovative businesses that are flourishing under minimal government regulations as ways to reduce costs for other businesses; and

- Restore or add work requirements to means-tested federal programs.

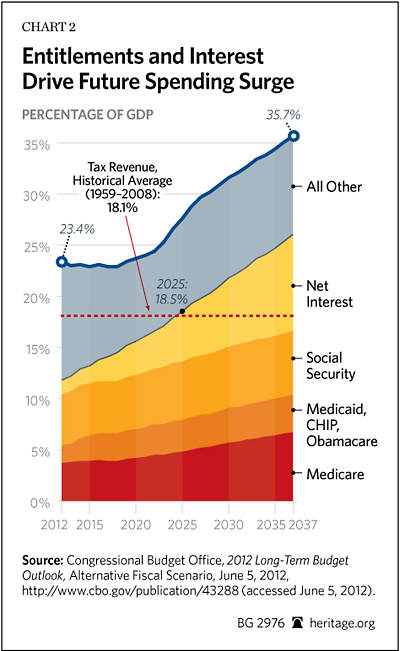

Following the Obama Administration’s Playbook on the Federal Budget

If policymakers follow IMF guidance, they run the risk of encouraging inaction by U.S. lawmakers, who must adopt structural entitlement reforms to control U.S. spending and debt growth. That is because the IMF emphasizes relatively minor institutional budget reforms to “lessen fiscal policy uncertainty,” citing “recent experience of debt ceiling brinkmanship and the government shut down,”[12] but withholds mention of any bold and fresh approaches to tackle America’s looming entitlement spending crisis that would truly serve the nation’s long-term interests.

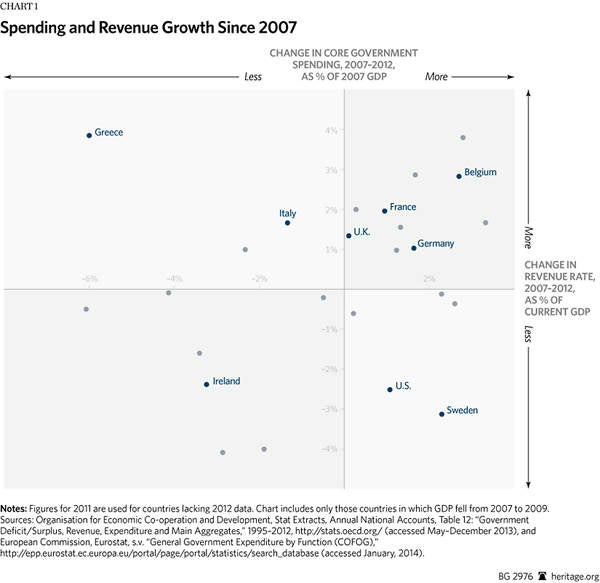

In so doing, the IMF’s meek suggestions seem to follow the Obama Administration’s federal budget playbook by focusing on immediate spending and tax increases—leaving even very modest entitlement tweaks for a future Administration.[13] Despite a doubling of the U.S. public debt in the years since President Obama came into office,[14] the IMF rashly calls for “expand[ing] the near-term budget envelope”—that is, actually increasing spending. To add insult to injury, the IMF report also recommends adding a national value-added sales tax (VAT) and job-killing new carbon taxes on top of the current U.S. tax burden, all of which would end up fueling even higher federal spending.

To its credit, the IMF does include a call for “[f]orging agreement on a credible, medium-term consolidation plan [that] should be a high priority and include steps to lower the growth of health care costs, reform social security, and increase revenues.”[15] In conjunction with the IMF’s suggestion to implement some of President Obama’s immediate spending initiatives, however, such an agreement at this point could be harmful: It would increase spending and taxes today and leave the U.S. on its dangerous fiscal trajectory. Adopting a budget agreement is important, but it cannot be just any budget agreement.

An IMF recommendation for carefully designed mechanisms to trigger revenue or spending adjustments if targets are breached—automatic triggers that kick in when Congress fails—are a key feature of successful fiscal consolidation plans. Such triggers should reduce spending to reduce the deficit and debt.

Unfortunately, in the current policy environment in Washington, automatically triggered tax increases would merely enable greater spending, which is the opposite of spending control. As Heritage economist Salim Furth points out, tax increases to reduce the deficit are much worse than spending cuts for the economy.[16] A spending trigger could operate like sequestration (which the IMF criticized),[17] or it could trigger actual policy reforms, such as increasing the retirement age, adopting a more accurate inflation index to curb entitlement benefit growth, or reducing benefits for upper-income earners.

The IMF also recommends an automatic process that would raise the debt ceiling once agreement is reached on the broad budget parameters. This recommendation appears to be designed to provide political cover for lawmakers who want to authorize additional borrowing.[18] Retaining the requirement that Congress vote to increase the debt ceiling has high public visibility and is an opportunity to hold Congress and the President accountable for failing to control spending and waste, and for authorizing money for pork projects.[19]

In keeping with the American tradition of checks and balances, Congress and the Administration must be publicly required to put the budget on a path toward balance with structural entitlement reforms.[20] They should stand accountable to the American people for any projected future debt increases. As Heritage analyst Romina Boccia wrote earlier this year:

A vote to increase the debt ceiling is a highly public affair and an opportunity to hold Congress and the President accountable for failing to control spending and waste and for authorizing money for pork projects. An actual debt limit forces Congress and the President to confront the debt limit more frequently. The fact that Congress has not increased the debt limit by an amount so large that it would not reach it for years is testament [to the fact] that constituents pay attention to debt limit votes and seek to hold their officials accountable for excessive borrowing.[21]

Another IMF recommendation would shift the budget cycle from an annual review to a two-year period (with the possibility of supplemental budget resolutions during that two-year window under clearly specified conditions). Proponents of the two-year budget cycle argue that it would provide more certainty to agencies about their funding.

Yet Congress already uses multiyear authorizations as a tool, and a two-year cycle is not necessarily the best time frame for multiyear projects. Proponents of the two-year cycle also argue that it would free Congress to conduct important oversight work. This assertion makes the very large and unrealistic assumption that Congress is falling behind in its oversight responsibilities for lack of time. Senator Tom Coburn (R–OK) says, “Ignoring their responsibility to conduct oversight and determine if a given federal program is effective, members of Congress are often beholden to special interest groups and would rather continue funding an old program instead of eliminating it.”[22]

As for the possibility of supplemental resolutions, a two-year cycle makes these very likely due to the estimating challenges for the $4 trillion enterprise known as the federal budget. As former House Budget Committee staffer Patrick Louis Knudsen has warned, more supplemental spending “would risk depleting the budget resolution as a vehicle for defining either public policy or fiscal discipline and would risk institutionalizing the spend-as-you-go practices of recent years.”[23] Finally, given the general breakdown of budgeting in Congress, a two-year cycle is no less likely to suffer from stop-gap measures, and could indeed exacerbate problems in the current process.[24]

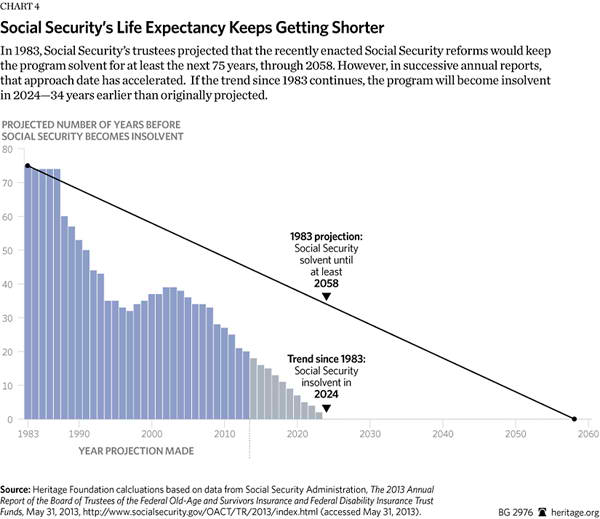

As recently as 2011, the IMF warned that the U.S. lacked a “credible strategy” to stabilize its mounting public debt.[25] Little has changed in the U.S. debt outlook since then: The U.S. still lacks a credible action plan to prevent public debt from growing far beyond the size of the U.S economy, or gross domestic product (GDP), before today’s preschoolers go off to college or work.[26] Such a strategy must begin with putting entitlement spending on a more sustainable long-term path, particularly by reforming health care and retirement programs for the elderly.

Recommendation: Instead of parroting Obama Administration policies, the IMF should return to the drawing board to identify budget reforms that will actually curb U.S. spending and reduce its debt.

Increasing the Payroll Tax Cap Will Not Fix U.S. Social Security

Due to the United States’ massive debt and unsustainable long-run deficits, the IMF necessarily recommends some policy reforms aimed at reducing future deficits, including Social Security’s deficits. Some of these recommendations are worthy of immediate implementation, but one would prove detrimental to economic growth.

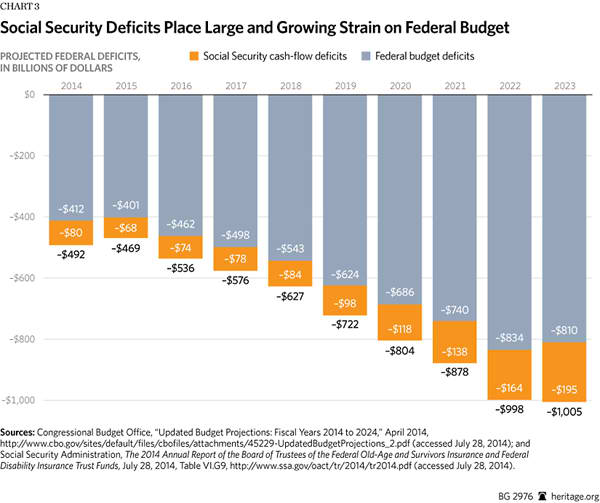

According to the most recent report by the Social Security Trustees,[27] the Social Security and Disability Insurance programs have a 75-year unfunded liability of $13.4 trillion.[28] This means that when the two trust funds run out of money in 2033 (under current projections), all Social Security benefits would be cut to about 77 percent of their previous or promised levels.[29]

The IMF report provides four recommendations to help shore up the Social Security program:[30]

- A further gradual increase in the retirement age (potentially with steps that link the future retirement age to average life expectancy or other actuarial indicators of the solvency of the system);

- An indexation of benefit programs and tax provisions to the chained consumer price index (C-CPI) (rather than the standard CPI);

- A modified benefit structure to increase progressivity; and

- An increase in the maximum taxable earnings for Social Security purposes.

Before evaluating these recommendations, it is important to consider the ultimate goals of reforming Social Security. The first goal is to return Social Security to its original intent of providing real insurance to prevent outliving one’s savings, as well as to supplement the income of elderly individuals who are no longer able to work. The second goal is to create a financing structure that ensures Social Security’s long-run financial security. Moving toward these two goals will increase the likelihood that the program remains viable for future generations of Americans.

Based on these goals of reform, the IMF’s first two recommendations should be implemented immediately, as they are both logical and straightforward to implement. The third recommendation deserves additional consideration, but the fourth should be dismissed outright because of the distortions it would create in the U.S. labor market and the drag it would create on economic growth.

The first recommendation in the IMF report makes sense given the fact that life expectancy in the U.S. has increased by 20 years since the first Social Security check was written in 1940.[31] Furthermore, the American economy has been transformed from an industrial to an information-based economy that has reduced the physical demands of most U.S. jobs. Consequently, Social Security has shifted from a program aimed at relatively short-term support for elderly individuals who are generally unable to work, to a program that provides potentially decades-long income support and that encourages individuals to stop working earlier than they otherwise might. Indexing the retirement age to life expectancy would better meet the program’s intended goal of supporting elderly individuals who are no longer able to work and who may have outlived their savings. Moreover, indexing the retirement age to reflect more realistic life expectancy would move the program toward long-run solvency and limit the need for future reforms.

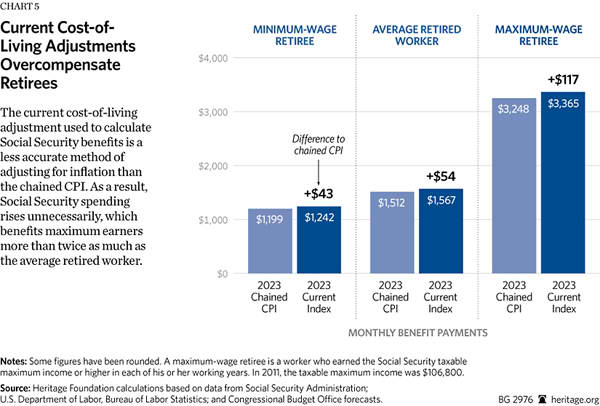

The second IMF recommendation, to replace the current inflation adjustment with the more accurate chained consumer price index (C-CPI), is another commonsense and achievable reform. The C-CPI is a more accurate measure of inflation than the standard CPI. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the C-CPI “provides a more accurate estimate of changes in the cost of living from one month to the next.”[32] Social Security’s current inflation-adjustment measure reflects prices paid by less than one-third of the population and it does not take into account the fact that people’s purchasing patterns respond to changes in prices.[33]

Implementing the chained CPI would maintain individuals’ purchasing power and would eliminate the existing policy of providing excess benefit increases. Moreover, high-income Social Security recipients benefit the most from the current inflation measure.[34] Over a 10-year period, for example, a high-income retiree receives $7,623 in excess benefit increases compared to only $3,549 for a median-wage earner and $2,813 for a minimum-wage earner.[35] Indexing tax provisions using chained CPI is separate from Social Security’s cost-of-living index, and should only be considered as part of broader tax reforms.

The IMF’s third recommendation to reform Social Security, which calls for a more progressive benefit structure, deserves consideration. As an income insurance program originally set up to help reduce poverty among the elderly, it makes little sense that Social Security provides the largest benefits to individuals with the greatest earnings while failing to provide even poverty-level benefits to the lowest earners.[36]

Rather than tinker with the benefit structure in a way that would still result in the highest earners receiving the highest benefits, Social Security could better achieve its goal of insurance against poverty in old age through a flat benefit at least equal to the poverty level. A flat benefit for all eligible Americans would have the added advantage of reducing overall revenue requirements, which would help confront the program’s unfunded liabilities and eventually allow a reduction in payroll taxes.

The IMF’s final recommendation calling for an increase in the payroll tax cap should be dismissed outright. Raising the payroll tax cap would result in exorbitant marginal income tax rates: The top combined federal and state income tax rate in California, for example, would amount to an astronomical 70 percent. Also, while raising the payroll tax cap would increase payroll tax revenues, it would reduce other federal, state, and local income tax revenues. Employers would respond to higher payroll taxes by reducing wages; as a result, other federal, state, and local income tax revenues would decline.[37] Additionally, both employers and employees would respond to higher taxes by shifting incomes to non-taxable benefits, reducing hours of work, and making other behavioral changes that would significantly reduce economic growth as well as total federal, state, and local tax revenues. Depending on the magnitude of these economic responses, raising the payroll tax cap would generate no more than 80 percent of statically projected revenue gains, and could in fact generate no net revenue increase at all.[38]

Although the IMF report does not provide specific recommendations related to the Disability Insurance (DI) component of Social Security, it does cite the DI Trust Fund’s impending insolvency in 2016. The DI program provides a vital safety net to millions of truly disabled Americans. To protect benefits for those who truly need them while also protecting the hard-earned tax dollars of working Americans, policymakers should carefully examine the DI program’s eligibility criteria and pathways to recovery. This could include fostering accommodations to keep workers with less severe disabilities employed, encouraging beneficiaries to return to work as they are able, and implementing reforms to the judicial process and continuing disability reviews to preserve the integrity of the DI program.[39]

Social Security is a significant contributor to the United States’ abysmal and unsustainable long-term fiscal outlook. The IMF report offers some commonsense reforms that could make a sizeable reduction in Social Security’s projected deficits, but additional reforms to the structure of the program, such as shifting to a flat-benefit payment, would improve the program’s finances for long-run sustainability, and target benefits more appropriately.

Recommendation: U.S. policymakers should ignore the IMF’s counterproductive recommendation to raise the payroll tax cap. An increase in the payroll tax cap would hamper economic growth in the U.S. and create a further drag on the sluggish U.S. labor-market recovery.

Other IMF-Recommended Tax Increases: Much Damage to U.S. Economy

The IMF report contains several other suggestions purported to provide ways for the U.S. to strengthen its economic recovery and improve the U.S. economy’s long-term outlook. In fact, in many cases, these recommendations would have the opposite effect. U.S. policymakers would do well to ignore almost all of them, too.

One of the IMF’s themes in the 2014 report is “keeping public debt on a sustained downward path.” There is certainly broad agreement that the U.S. must reduce the size of future deficits soon. The disagreement lies in how to achieve it.

The IMF would have the U.S. reduce its deficits by massively increasing the burden it inflicts on American taxpayers. It wants Congress to raise taxes by:

- Instituting a VAT;[40]

- Repealing or scaling back the mortgage-interest deduction;[41]

- Significantly raising the gas tax; and

- Raising income taxes through greater real bracket creep with the chained CPI.

IMF-proposed tax increases could take additional trillions from Americans each year. All that extra revenue flowing to Washington would greatly increase the size of the government and shrink the private sector. It would stifle economic growth, which would contradict the IMF’s stated goal of helping those in need. The IMF proposes that Congress reduce taxes by a comparatively trifling amount by increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit and offering an ineffective hiring tax credit.

A VAT alone could increase Americans’ tax burden by trillions each year. Most developed countries have VATs. The U.S. is the rare exception. The lack of a VAT is one of the ways the U.S. has been able to keep its tax burden relatively low. Businesses remit the VAT to the government at each stage of the production process, and customers ultimately bear the entire burden of the tax. To consumers it might seem like a retail sales tax. It can raise huge amounts of revenue from taxpayers inconspicuously, however, because unlike the sales taxes most U.S. states levy, the VAT does not have to be printed on receipts. It can be imbedded in the price of products. That is why lawmakers in countries with expensive and big governments favor it. Adding a VAT on top of all the other taxes Americans already pay would allow Washington to expand greatly—and quietly. This is a major reason it should be avoided.

Repealing, or scaling back, the mortgage-interest deduction is another bad IMF proposal. Under an income tax such as the U.S. has, if interest income is taxable to lenders, it should be deductible to borrowers. A deduction is not necessary if interest income is untaxed. Either method prevents taxes from artificially influencing investment decisions. If the U.S. followed the IMF’s suggestion, it would allow the tax code to be a negative influence on investment in housing. Contrary to popular opinion, because mortgage lenders pay tax on their interest income, the mortgage-interest deduction keeps taxes from negatively influencing the decisions of families to buy homes. Properly understood, it is not a subsidy. The only way Congress should lessen the mortgage-interest deduction, or any interest deduction, is if it simultaneously eliminates tax on interest income, although this type of reform is not what the IMF has in mind. The IMF desires a tax increase, the negative consequence of which it apparently does not consider.

A higher gasoline tax would be similarly detrimental. The gas tax is intended as a user fee to fund roads, bridges, and other surface transportation infrastructure. However, at least a quarter of gas tax revenue funds other projects, such as bike paths, mass transit, and interpretative (explanatory) signage in places such as national parks. A significant portion of a higher gasoline tax receipts, therefore, would go to these projects instead of those that Congress intended to fund through the legislation. Congress should refuse to consider changing the gas tax until the federal government reverts to a system that fully appropriates those revenues only for the purposes for which they were originally intended.

The chained CPI presents a more accurate measure of inflation. Nevertheless, indexing current marginal tax rate brackets to the chained CPI would be another significant and inappropriate tax increase. Tax brackets that determine the marginal tax rates that Americans pay are adjusted upward each year so taxpayers only pay taxes when they have real, post-inflation income increases. Switching to the chained CPI for income tax purposes would raise taxes because brackets would rise less each year, thus subjecting more income to higher rates. While it would make sense to switch to chained CPI in tax reform where such a change could be offset by other policy changes so it does not raise tax revenue overall, doing it outside of such a process would be nothing more than another revenue grab.

The IMF makes two worthwhile suggestions that Congress should heed: (1) It wants Congress to make the research and development (R&D) credit permanent, and (2) reform the badly outdated corporate income tax system.

Updating the corporate tax system for the 21st century is vital for restoring economic growth. At 35 percent, the U.S. has the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world as defined by members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and is one of only a few in that group that taxes the foreign income of its businesses. The antiquated system is the reason for the recent wave of corporate “inversions”—the practice of U.S. businesses merging with a foreign entity and moving the new business headquarters outside the U.S. Other developed nations have lowered their rates and stopped taxing foreign profits by moving to territorial systems in recent years. The U.S. fell significantly behind by standing still.

To update the system, Congress needs to lower the corporate tax rate to no more than the 25 percent that is the OECD average (and preferably lower, because individual U.S. state corporate income taxes increase the overall rate). Also, the U.S. should switch to a territorial system that would no longer tax the income that U.S. businesses earn abroad.[42]

If the U.S. implemented the IMF’s recommendations, the American economy would come to resemble (even more than it already does) the economies of many European nations. These countries have substantially higher taxes, much larger governments, commensurately smaller economies, and fewer economic opportunities in general. Perhaps this is not surprising since many of the economists at the IMF are, in fact, proponents of the European welfare state model.

Recommendation: U.S. policymakers should consider the source of this policy advice, and ignore most of it. (The two exceptions are the recommendations to update the corporate tax system and to make the R&D credit permanent.)

Obama, Wall Street, and the IMF: All Wrong on Carbon Taxes

Another IMF recommendation is that the United States “should introduce a broad-based carbon tax.”[43] In so doing, the IMF thus echoes the Obama Administration, which has been calling for carbon-cutting policies ever since taking office.[44] Establishing such a tax on carbon emissions would increase unemployment and fail to raise additional revenue for the government.[45]

The IMF report is similar to another study—by former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg titled “The Economic Risks of Climate Change in the United States.” Paulson and Bloomberg also advocate the imposition of U.S. carbon taxes.[46]

The IMF position also echoes previous policies promoted by IMF managing director Christine Lagarde—a long-time advocate of carbon taxes—as well as IMF staff in previous consultations. As French finance minister, Lagarde was on a 21-member United Nations panel that produced a 2010 report calling for the mobilization of “$100 billion a year by 2020 to help poor countries adapt to climate change and reduce emissions of carbon dioxide trapping the sun’s heat.”[47] In 2004, the IMF staff advocated higher energy taxes in the U.S. and pushed specifically for carbon taxes after the Obama Administration took office in 2009.[48]

The IMF case for carbon taxes is misguided. As The Heritage Foundation’s Nick Loris explains, a “carbon tax would be an enormously high, regressive energy tax that would needlessly destroy jobs and economic growth.”[49] To make matters worse, the tax would not make a dent in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions and therefore would have no noticeable impact on global temperatures.[50] In addition, carbon taxes are regressive and fall most heavily on the poor.[51]

Recommendation: The U.S. should reject the carbon tax. Instead of listening to the IMF, U.S. policymakers should follow the lead of Australia which, led by a new conservative government, repealed Australia’s distortionary and job-killing carbon taxes this year and lifted price controls on electricity to encourage market-based production of power.[52]

IMF Solution to Safer Financial System: More Risk for U.S. Taxpayers

In sections of the Article IV consultation report dedicated to areas such as housing finance and banking regulation, the IMF’s proposals have a common theme—more government intervention and greater risks for the American taxpayer, instead of an emphasis on market-based solutions.

IMF Report Gets Housing Finance Wrong. The IMF report highlights the importance of achieving a safer financial system. Its policy recommendations would, however, achieve just the opposite, while putting U.S. taxpayers at risk.[53] For example, the report recommends that the U.S. create a housing finance system that includes the following:[54]

- A substantial first-loss risk borne by private capital (rather than taxpayers);

- An explicit public backstop that is limited to catastrophic credit losses with risk-based guarantee fees; and

- A role for regulatory agencies in setting underwriting standards.

These supposed reforms appear to be taken directly from the housing finance bills that recently stalled in the U.S. Senate. The main problem with these ideas is that they would leave the U.S. housing market in nearly the same state it was in before the 2008 financial crisis.[55]

One of the only real differences from these proposals and the pre-crisis U.S. housing finance market is that these plans would convert implied government backing into explicit government backing—hardly a win for U.S. taxpayers.

Under these proposals, new companies would replace the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which were bailed out by U.S. taxpayers in 2008. These new companies, just like Fannie and Freddie, would be bailed out in the event of a catastrophic failure. The difference is that this bailout would be made explicit ahead of time instead of simply implied, as it was prior to 2008.

Supporters of the proposed Senate bills claimed that the legislation would require more private capital (from the new firms) than the GSEs had. This argument ignores the fact that the GSEs started out with strong capital requirements. Congress has never been able to maintain adequate private capital requirements at these institutions, so there is simply no reason to expect a different result this time.

The IMF’s recommendation is even stranger given its preoccupation with financial stability. The U.S. housing system, with a more extensive system of government guarantees in the housing market than nearly all other developed nations, suffered a more severe downturn than most countries. For instance, U.S. volatility of home prices and home construction from 1998 to 2009 was among the highest in the industrialized world.[56] Furthermore, mortgage default rates in Western Europe and Canada were much lower than in the U.S., even amid rapidly falling home prices during the 2008 crisis.[57]

Recommendation: Notwithstanding all of the predictable negative outcomes outlined above, the IMF has decided to promote policies that would propagate the less-stable U.S. system. They should not be followed.

IMF Report Gets Financial Stability Wrong. The IMF report promotes the idea of regulatory harmonization and urges U.S. leadership in this regard. The report states that the “U.S. should also continue to play a lead role in advancing the global regulatory reform agenda, ensuring common practices across countries, and limiting the opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.”[58]

While the idea of regulatory harmonization across countries sounds plausible on the surface, in fact it would encourage or require all banks and financial firms to act in lockstep, taking the same risks, opting for the same investments, and catering to the same investors. This, of course, is the classic recipe for bubbles, which in turn are the classic cause of financial crashes.

Thus, promoting a single regulatory framework for all of the world’s financial firms could actually result in more instability—the opposite of what the IMF purports to want. For instance, the Basel requirements (first implemented in the 1980s) encouraged firms to hold the same types of assets. A main cause of the recent crisis was that so many firms purchased mortgage-backed securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to lower their capital costs specifically because the Basel system assigned these assets low-risk weights.[59] As a result, the entire financial system was susceptible to any problems with just that one class of assets. Adopting one common framework going forward, then, would lead to more fragile financial markets.

Recommendation: U.S. policymakers should give agencies such as the Federal Reserve less regulatory authority, not more, and give no credence to the IMF’s suggestions of standardizing the risks that all financial firms can take.

IMF Report Gets Capitalism Wrong. Even more broadly, the IMF ideas in these sections of the report reinforce the impression that the IMF favors a heavily regulated, European-style economy instead of a vibrant private capital market. The IMF report echoes and repeats several anti-market myths—as well as the so-called solutions to these supposed problems—currently being propagated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) that the Dodd–Frank financial-regulation law created in 2010. The FSOC is the committee of regulators responsible for identifying so-called systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs).[60] The IMF report states:

In particular, a tail risk where there was a precipitous attempt by investors to exit certain markets—perhaps exacerbated by outflows from ETFs [exchange-traded funds] and mutual funds as well as near-term market illiquidity—could trigger an abrupt and self-reinforcing re-pricing of a range of financial assets.[61]

This passage amounts to an endorsement of the FSOC’s report on asset-management firms that suggests asset managers should be highly regulated because they allegedly cause systemic risk.[62] Asset managers make purchases only on behalf of their customers, so they collectively owe them nothing in the event of a market crash. Customers accept the risk, and asset managers merely transfer funds—their activity does not add to systemic risk.

Nevertheless, the FSOC is currently setting the stage to pre-identify large asset managers as SIFIs. This process would itself create systemic risk because it would announce to the market that the government will not let these firms fail. Since the FSOC’s authority is so broad and the SIFI designation process is so ill defined, all financial firms will face constant uncertainty over which sort of regulations will be handed down next. The proposed SIFI process biases the financial system in favor of riskier behavior because it minimizes the chances that creditors will lose money.

Recommendation: Overall, the FSOC leads a massive top-down regulatory approach that can ultimately dictate to companies which financial activities are acceptable. This approach is wholly incompatible with a private market, and the U.S. should reject it.

Conclusion

Every year, the long-term economic survival of the United States is more imperiled by the continuing failure of U.S. policymakers to deal with the crisis of growing entitlement spending (such as on Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security). Right now that spending is locked on autopilot to an unsustainable future. IMF analysts understand these risks well enough but they, also, have failed to deal with them. Instead of fulfilling the IMF’s mandate to put forward politically difficult but sensible budgetary proposals and other fiscal and monetary solutions that would reduce the role of the government in the economy, IMF analysts have joined the chorus of what Ronald Reagan used to call the Washington “tax-and-spend” crowd. In so doing, Professor Mankiw’s “free-lunch thinkers” at the IMF have become part of the problem.