Medicare Advantage (MA) is a program of competing private health plans. For the vast majority of senior citizens, it is the only viable alternative to enrollment in traditional Medicare. For Members of Congress, its record also provides valuable lessons for comprehensive Medicare reform.

MA is an increasingly attractive option for millions of senior and disabled Americans because it offers comprehensive coverage, and, typically, a more generous benefits package than traditional Medicare. By law, MA plans must provide at least the same benefits as traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare Parts A and B. But unlike traditional Medicare, MA plans must also put a cap on beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs. It also provides patients with a variety of plans (ranging from managed care and private fee-for-service plans to “special needs plans”); a broad array of doctors, hospitals, and other medical professionals; and additional benefits and services on a competitive basis. MA plans have also made pioneering changes in care delivery, such as care coordination and case management. Today, the program has 15.7 million enrollees, almost 30 percent of the entire Medicare population.[1]

Despite the program’s increasing popularity among a growing share of Medicare enrollees, it is often criticized for costing more per enrollee than the traditional Medicare program. Though this criticism is technically accurate, critics tend to disregard the simple fact that the program’s payment design intentionally produces this undesirable result. This is a statutory flaw, not a market failure. Moreover, the higher MA payments have allowed its plans to not only offer true insurance with catastrophic coverage—a cap on out-of-pocket expenses—but also to offer additional benefits. Since the program’s inception, this arrangement has resulted in higher enrollee satisfaction and significant savings for seniors, particularly on out-of-pocket medical costs.[2]

Payment Reductions. MA payment reductions, widely supported by liberals in Congress well before the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010, would invariably translate into Medicare benefit cuts. Because “excessive” MA payments often provide patients extra benefits or lower cost sharing, reductions in these payments amount to cuts in these extra benefits. In 2009, Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Director Douglas W. Elmendorf told the Senate Finance Committee that the MA payment cuts required in the Senate version of the bill that was to become the PPACA would indeed result in benefit cuts.[3] Nonetheless, while insisting that their proposed MA payment reductions would affect only plans and providers, not Medicare patients, in 2010 President Barack Obama and Congress enacted substantial MA payment reductions.

The Administration’s goal was to more closely align MA plan payments with traditional Medicare fee-for-service spending. The CBO projects that if these MA payment reductions are to be executed as the law provides, they will amount to $156 billion from 2013 to 2022. When the PPACA was enacted in 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Actuary projected that the law’s payment cuts and other program changes would decrease enrollment in the program by 50 percent after they were fully phased in, significantly jeopardizing the program’s viability.[4]

Today, there is a noteworthy disparity in the changing estimates of government analysts at the CBO and the Medicare Board of Trustees over the impact of the health law’s payment changes on the growth of MA enrollment.[5]

Reform Potential. Congress and the Administration are overlooking the potential of the Medicare Advantage program as a starting point for broader Medicare reform. Instead of creating counter-productive “savings” by implementing policies that are likely to damage the MA program or negatively impact seniors, as the PPACA does, policymakers should learn from the lessons provided by MA experience and apply them to a structural Medicare reform, based on the principle of defined-contribution financing that characterizes the MA program. Comprehensive Medicare reform should incorporate the best features of Medicare Advantage without replicating the obvious flaws—namely, its existing payment system that, in point of fact, has contributed to higher and unnecessary taxpayer costs.

If Congress were to adopt a comprehensive Medicare reform based on a defined-contribution (“premium support”) financing system, as proposed by several Members of Congress and The Heritage Foundation,[6] lawmakers could automatically deem Medicare Advantage plans competitors in the robust new market. However, plans would have to make a number of systemic changes with such a reform to improve patient choice, market competition, and program efficiency.

The most important of these changes would be a new financing arrangement, based on market-based bidding among health plans that would reflect the real-market conditions of supply and demand. This should be entirely separate from the current administrative pricing that governs traditional Medicare and affects Medicare Advantage. Other changes would include a broadening of benefit offerings, including the provision of willing employer-based coverage for retirees and an improvement in the Medicare risk-adjustment system.

How Medicare Advantage Payment Works

While MA’s payment system directly benefits senior citizens, primarily in the form of richer benefits or lower costs, it has nonetheless been a continuing source of controversy since its inception because it generates higher health care spending than if these Medicare patients were to be enrolled in traditional Medicare.

In traditional Medicare, the government reimburses doctors, hospitals, and other medical professionals on an FFS basis, paying a set fee determined administratively on the basis of the relevant formulas for delivering care for a set of defined benefits. This complex FFS payment system, reinforced by price caps or controls, is at the heart of traditional Medicare.

When Congress enacted the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, it significantly changed government reimbursement of private health plans in Medicare Advantage. Henceforth, plans were to be paid on a per capita basis, adjusted for risk scores, using a process of competitive bidding for the provision of Medicare benefits and services. Each year, the government sets a Medicare benchmark payment for the cost of providing traditional Medicare in designated geographic areas or regions around the nation. In each geographic area, the health plan providers submit bids to provide the traditional Medicare benefits, Part A (inpatient care) and Part B (outpatient care). If the private health plan bid exceeds the established Medicare benchmark payment for that geographic area, the enrollees in that plan pay the difference above the Medicare benchmark in the form of a higher premium. If the health plan bid falls below the Medicare benchmark, the plan is legally prohibited from offering the enrollees a cash rebate. Instead, the plan is required to rebate 75 percent of the difference between the Medicare benchmark and the plan bid back to enrollees in the form of lower premiums or additional health benefits. The remaining 25 percent of the savings from a bid below the benchmark is to be earmarked as savings for the Medicare program.

As a practical matter, the average MA plan bids below the Medicare benchmark payment. Under the bidding process in 2014, for example, the average bid is 98 percent of the projected FFS spending for similar beneficiaries. Some plan providers bid well below the benchmark, and some bid much higher. According to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC), the agency that advises Congress on Medicare provider payment, “About 48 percent of non-employer plans bid to provide Part A and Part B benefits for less than what the FFS Medicare program would spend to provide these benefits.”[7] (Emphasis added.) This means, of course, that these competing private plans are economically more efficient than traditional Medicare in delivering the traditional Medicare benefits in that given area.

PPACA-Mandated Changes. With the enactment of the PPACA of 2010, Congress and the Administration made further changes in the MA formula, phasing in these adjustments over five years (2012 to 2017). Henceforth, government payments to health plans are to be based on new government benchmarks that range from 95 percent to 115 percent of the local costs of traditional Medicare. These new benchmarks are designed to align MA payment more closely with traditional Medicare.

Under the national health law, the 75 percent share of the rebate to MA plans is replaced with new rebate levels based on plans’ compliance with the government’s “five star” performance standards for the delivery of quality care. For the highest scoring plans (between 4.5 stars and 5 stars), the rebate share is 70 percent; for those with scores between 4.5 stars and 3.5 stars, the share is 65 percent; for those below 3.5 stars, the share is 50 percent.[8] The change, effective in 2012, is to be phased in over three years.

While seniors will be on the receiving end of lower rebates by as much as 25 percent, MA plans will also incur higher costs because of the new federal health insurance fee—a special health insurance tax effective in 2014 to finance the PPACA—that applies to private health insurance generally. Moreover, in addition to other PPACA Medicare payment reductions, under the sequestration provisions authorized by the Budget Control Act of 2011, MA plan payments will further be reduced by 2 percent between 2013 and 2024.[9]

In short, as the Medicare trustees report, MA plans will experience lower payment benchmarks in “most areas” of the country, and will also be negatively affected by federal budget law, the PPACA insurance tax, and the broader ACA payment reductions in traditional Medicare itself. They write that “the productivity offsets to Medicare fee updates and other savings provisions of the Affordable Care Act will dampen the projected increase in the per capita fee for service base of the benchmark.”[10]

The Medicare trustees report that these changes will impact MA enrollment. While MA enrollment is projected to increase by 9 percent in 2014, enrollment growth is projected to slow in the near future. The trustees state:

Now that the majority of the Affordable Care Act benchmark phase-in is complete, it can be seen that the decrease in the blended benchmark did not have as large an impact on enrollment as previously assumed. In years 2015 through 2018, when the benchmark changes have fully phased in, the enrollment growth rate is expected to slow substantially, ranging between 1 to 4 percent annually.[11]

Total MA enrollment is projected, according to the trustees, to stabilize at 32 percent of total Medicare beneficiaries in 2025.[12]

The CBO, as noted, has made different projections on the impact of the PPACA payment changes on the growth of MA enrollment. So, the best that can be safely said, based on conflicting data from government actuaries, as well as the political volatility surrounding the enforcement of the law’s payment reductions, is that the future MA enrollment is uncertain. It is too soon to know how MA plans will react to the scheduled payment reductions or how beneficiaries will respond.

Fixing the Flaw. The MA payment system has been the program’s major flaw—linking private-plan payment to spending in Medicare’s FFS system causes unnecessarily higher costs for taxpayers. A much better policy would be to implement straight competitive bidding among private health plans with the government benchmark payment to MA plans based solely on those competing market bids, entirely separate from traditional Medicare spending. In fact, both the Clinton Administration in 1999[13] and the Obama Administration in 2009 proposed such a superior bidding process for the Medicare Advantage program.[14] Unfortunately, the Obama Administration abandoned its initial MA payment proposal in favor of the scheduled Medicare payment reductions enacted as part of the PPACA.

The MA payment system, tied inextricably to Medicare’s administrative payment system, has undercut the potential for serious cost savings. For example, plans could not pay rebates in cash to seniors, or simply offer a leaner and lower-cost set of health benefits. If, in any given region of the country, the Medicare benchmarks were too high, that was due to a structural deficiency of traditional Medicare’s administrative pricing, which overpriced medical services in some areas of the country and underpriced them in others. Nonetheless, current law still ties Medicare Advantage payments to this flawed system of traditional Medicare’s administrative pricing.

There are several better options for setting the annual payment to competing health plans. For instance, the government payment could be set at the bid of the second-lowest-cost plan or the average bid of all competing plans in a geographic region. In addition, any savings generated by picking a plan that bids below the benchmark, should be allowed to go straight to the senior citizen who made that cost-conscientious decision.

Why Seniors Like Medicare Advantage

The MA program has rapidly expanded over the past decade, and overall, seniors are happy with the program. Indeed, enrollees are more satisfied with their Medicare Advantage plan than enrollees in traditional Medicare. According to a 2014 survey, 94 percent of MA enrollees are very or somewhat satisfied with their Medicare Advantage plans, in comparison to 85 percent of seniors enrolled in traditional Medicare.[15]

The MA program offers several clear advantages over traditional Medicare. The main advantages for senior and disabled citizens are reduced out-of-pocket costs, the security of catastrophic coverage protection, additional benefits, such as drug or vision coverage, and a wider range of plans and health benefit options.

Lower Premiums. MA’s premium performance has been an especially attractive feature for Medicare patients. From 2010 to 2011, the average monthly premium declined from $44 to $39. In 2012, it declined again to $35 where it has remained for the third year in a row.[16] In fact, in 2014, 84 percent of MA beneficiaries have access to a zero-premium plan that includes drug coverage, meaning they have no premium payments other than the regular Part B premiums.[17] However, the requirement that MA channel savings into richer benefits or reduced premiums, rather than allowing cash rebates, undercuts the MA program’s potential for cost control.

Better Coverage. MA plans include catastrophic coverage, clearly the most important benefit in any health insurance plan,[18] protecting seniors from the financial devastation of serious illness. In other words, Medicare Advantage provides real insurance, and is an enormous improvement over the traditional Medicare program. MA plans are required to cap out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries at $6,700 (with a recommended cap of $3,400). In contrast, traditional Medicare does not protect beneficiaries from endless out-of-pocket expenses, encouraging about 90 percent of traditional Medicare enrollees to purchase supplemental insurance separately, adding another premium to their out-of-pocket medical costs.

MA plans also participate in Medicare Part D, the Medicare prescription drug program, which offers a wide variety of pharmaceuticals at competitive prices. Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug (MA–PD) plans enrolled 12.8 million beneficiaries in 2013.[19] As previously noted, 84 percent of enrollees in 2014 have access to an MA plan that includes drug coverage and has no premium beyond the Part B premium.

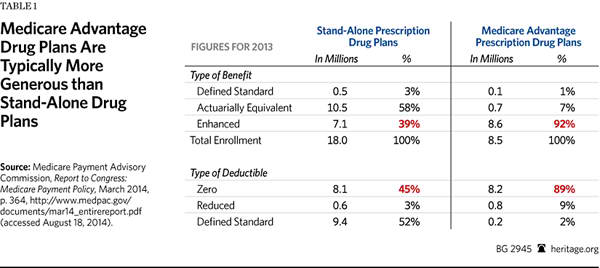

In addition, enrollees in MA–PD plans are more likely than those enrolled in stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) to be enrolled in an enhanced plan. Enhanced-benefit plans have a greater actuarial value than basic plans, meaning that they provide more generous coverage. For instance, they provide insurance for drugs filled during the gap in coverage (beyond what is now mandated by the PPACA), or reduced or eliminated deductibles. Indeed, 92 percent of MA–PD enrollees were in an enhanced plan, compared to only 39 percent of PDP enrollees.[20]

Higher Quality Care. Medicare Advantage delivers higher-quality care to patients enrolled in the program than patients receive who are enrolled in traditional Medicare in certain areas. For example, in 2006 and 2007, the performance for MA patients, based on 11 measures of quality from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set,[23] scored higher than traditional Medicare patients on eight of the 11 criteria; they scored slightly better on only one of these criteria, and scored worse than traditional Medicare enrollees on only two.[24]

By focusing on better care coordination, health plan officials hope to improve patient outcomes, reduce avoidable hospitalizations, and increase savings. Well before the enactment of the PPACA, MA plans had made significant progress in achieving this widely shared objective. Based on 2005 and 2006 data, researchers from the Center for Policy and Research at America’s Health Insurance Plans found that MA heart and diabetes patients had equal or lower average rates of hospital admissions, re-admissions, and emergency room visits compared to traditional Medicare patients. MA patients with diabetes had lower rates of potentially avoidable admissions in seven out of eight plans. MA heart patients had similar outcomes in six of eight health plans.[25]

For dual-eligible patients, low-income seniors covered by both Medicare and Medicaid, the quality metrics are also impressive. This is particularly important since this is a complex and challenging class of Medicare patients. For example, Avalere Health’s 2012 study of Mercy Care Plan in Arizona found that enrollees had a 31 percent lower discharge rate, 43 percent lower rate of days spent in the hospital, 19 percent lower average length of stay, 9 percent lower rate of emergency visits, and a 21 percent lower readmission rate than dual-eligible beneficiaries nationwide who are enrolled in traditional Medicare.[26]

Medicare Advantage’s Mixed Record on Cost Control

On a per capita basis, the government indeed spends more on Medicare Advantage enrollees than it spends on traditional Medicare. That discrepancy has been at the center of debate in Congress and elsewhere on the relative merits of Medicare Advantage compared to traditional FFS Medicare. In 2014, MA spending per enrollee averaged 106 percent of spending per traditional Medicare enrollee.[27]

In recent years, simple cost comparisons between Medicare and Medicare Advantage have been superficial. While the higher per capita spending in Medicare Advantage has tracked the administratively determined benchmark, Medicare beneficiaries were saving substantially on out-of-pocket costs, while receiving more benefits—albeit at an added expense to taxpayers.[28]

Less Demand for Medigap Coverage. There are also ways, however, in which Medicare Advantage is actually reducing federal spending and thus saving taxpayers’ money.

Because traditional Medicare does not protect beneficiaries from catastrophic costs, about nine out of 10 traditional Medicare enrollees purchase Medigap or depend on other supplemental coverage. Medigap plans provide crucial “wrap-around” coverage for patients enrolled in traditional Medicare, and that extra coverage invariably includes protection from the devastation of catastrophic illness. As of December 2012, 10.2 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medigap plan, about one-fourth of the total Medicare population at that time.[29] Beyond the necessary catastrophic protection, many of these supplemental plans pay traditional Medicare’s deductible and cost-sharing obligations, thus providing first-dollar coverage for services. In short, the Medicare enrollees in these plans pay nothing at the point of service. This drives excessive utilization of services and thus higher costs.

The current arrangement between traditional Medicare and Medigap and other supplemental insurance is a major cost driver in the Medicare program. In 2011, MEDPAC concluded, “By effectively eliminating any of FFS Medicare’s price signals at the point of service, supplemental coverage generally masks the financial consequences of beneficiaries’ choices about whether to seek care and which types of providers and therapies to use.”[30]

This arrangement, then, contributes to excessive spending in traditional Medicare. There is a broad academic consensus that the existing relationship between traditional Medicare and supplemental coverage drives up spending for taxpayers and beneficiaries. Indeed, a major study, commissioned by MEDPAC, concludes that, “All of the available evidence suggests that secondary insurance raises Medicare spending substantially.”[31] This increased spending, according to MEDPAC, is almost solely due to beneficiaries with supplemental coverage who pay less than 5 percent of Part B costs out of pocket. Likewise, MEDPAC reports that total Medicare spending was 17 percent higher for beneficiaries enrolled in employer-sponsored coverage, and was 33 percent higher for beneficiaries with Medigap, than those with no supplemental coverage.

Thus, supplemental coverage, particularly Medigap, results in a hidden cost shift to seniors. Part B premiums are fixed at 25 percent of the total program cost for beneficiaries. So, if this excess use is contributing to higher federal spending on Part B, it is simultaneously contributing to higher beneficiary premiums. Medicare beneficiaries’ premiums are thus inflated. In an attempt to quantify the added beneficiary costs, the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Data Analysis (CDA), building on MEDPAC research, estimated that the total additional 10-year increase in beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket Part B spending would amount to $70.1 billion by 2023.[32] The CDA also estimated that cumulative beneficiary premium costs of Medigap coverage alone (that is, excluding employer supplemental coverage) would amount to $334 billion by 2023.[33]

Medicare Advantage beneficiaries still pay the Part B premium, and thus are affected by the additional costs that result from Medigap policies. However, they are saving the taxpayers money by not contributing to this problem because the purchase of supplemental coverage is unnecessary in the MA program.

In addition, MA beneficiaries save a considerable amount of money for themselves because they do not have to purchase supplemental coverage. Average premiums in Medigap can be quite substantial. According to a 2011 report from the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the Department of Health and Human Services, “The more comprehensive and more popular plans, C and F, cost an average of $178 and $171 per month, respectively, while the plans with higher out-of-pocket spending, K and L, cost an average of $82 and $121 per month, respectively.”[34]

It would be well for the CBO or the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to undertake a comprehensive econometric analysis that clearly delineates the interaction of Medicare Advantage with Medigap or other supplemental coverage, and determine the extent to which the current law relationship contributes a net savings or loss to the taxpayers. It would also be worthwhile for the CBO or the GAO to study the interaction of Medicare Advantage and Medicaid and determine the extent to which the enrollment of lower-income dual-eligible persons in MA reduces taxpayers’ obligations. Past independent research has clearly indicated that MA enrollment was indeed an offset to rising Medicaid costs.[35]

On the issue of cost savings, the record has been mixed. Medicare Advantage has been clearly generous to beneficiaries who enroll in the program, and it unquestionably incurred a higher per capita cost than traditional Medicare. But the higher costs also matched a higher level of benefits. To the extent that integrated MA coverage has also been an excellent substitute for expensive Medigap and other supplemental coverage, Medicare Advantage has been a cost saver, not a cost driver.

Lessons from Medicare Advantage for Premium Support

The MA program has been successful in terms of beneficiary satisfaction; and, based on the plan bids submitted, it is clear that private plans, offering comprehensive coverage, are able to provide the Medicare benefit for less than the cost of traditional Medicare. It is for these reasons that Medicare Advantage should be used as a model for the comprehensive Medicare reform premium support, a system of defined-contribution financing. Policymakers should:

- Not underestimate the role of personal choice. There is a wide body of research surrounding various aspects of the MA program and, although premium support would not be an identical program, MA’s history provides good lessons for lawmakers on the transition to a choice program based on premium support.

Research shows that despite Medicare Advantage clearly being a better choice for many beneficiaries, offering enhanced benefits and reduced costs, the vast majority of beneficiaries remain in traditional fee-for-service plans. According to researchers at the Harvard Medical School and the Harvard School of Public Health, this is not because of “choice overload,” but largely due to status quo “bias.” New Medicare enrollees are enrolling in Medicare Advantage at a much faster rate, and those that make their initial choice to enroll in a fee-for-service plan are less likely to switch into an MA plan. The Harvard researchers found that:

Over 2007–2010, the rate of MA enrollment was significantly higher among new Medicare beneficiaries than among incumbents, suggesting that enrollees who chose [traditional Medicare] before this period were unlikely to revisit their choice.… Among new entrants into Medicare, the overall rates of HMO/PPO and PFFS [private fee-for-service] enrollment are 9.9 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively. In contrast, rate[s] of enrollment into MA from [traditional Medicare] among beneficiaries age 66+ are much lower: 1.8 percent and 2.1 percent for HMO and PFFS enrollment respectively.[36]

This recent research suggests that status quo bias plays an important role in determining why Medicare patients behave the way they do. In addition, many critics of Medicare premium support and of private competing health plans in general argue that too much choice is a bad thing, leading to confusion among seniors. However, as the Harvard researchers note, “We did not find much evidence in support of choice overload in the MA market; MA enrollment did not decline with an increase in the number of plans, although among incumbent beneficiaries it failed to increase.” In 2014, MA beneficiaries had access to an average of 10 plans from which to pick.[37] - Not delay a move toward Medicare premium support. The lesson is that the sooner Congress can act, the better. In their 2014 report, the Medicare trustees, without endorsing any particular course of action, stress that Medicare’s financial problems will require serious reform, and that legislative action should not be delayed.[38]

With particular relevance to premium support, the research, cited above, shows that having the option to enroll in a private plan versus traditional Medicare is most valuable when an enrollee makes the initial coverage decision upon entering eligibility at age 65. The premium support program would be able to enroll a greater share of beneficiaries at a faster rate the sooner it is implemented. This is critically important as the baby-boomer generation has been becoming Medicare eligible since 2011 and will continue to do so through 2030. The Medicare program needs to realize savings from premium support as soon as possible, and an earlier start date would likely lead to greater enrollment.

The CBO has projected significant savings from the implementation of premium support,[39] with greater savings the more enrollees choose a private plan over traditional Medicare. Thus, if a greater share of new enrollees are choosing private plans and revisiting their choice once enrolled in traditional Medicare is rare, starting the program as soon as possible will help secure greater savings due to greater enrollment in private plans. - Set payment on market-based bidding, not government price controls. The premium support contribution should be different from MA payment in a critical way: It should not be statutorily linked to administrative pricing and payment in traditional Medicare. Premium support would provide a defined amount of money to seniors to offset the cost of a plan they pick. The per capita government payment would be based on a regional bid to provide Medicare’s existing benefits (Parts A and B, as well as catastrophic coverage and the standard drug benefit). Where the benchmark is set matters greatly to the program’s overall ability to achieve savings.

There are varying proposals on how the benchmark payment in premium support should be determined. In the Heritage proposal, the government payment would be based on an average of the three lowest-cost plans in the region.[40] In Senator Ron Wyden’s (D–OR) and Representative Paul Ryan’s (R–WI) proposal, the benchmark payment is set at the second-lowest-cost private plan in an area, or at Medicare fee-for-service cost, whichever costs less.[41] The proposal by former Senator Pete Domenici (R–NM) and former CBO director Alice Rivlin, also referred to as the Bipartisan Policy Center proposal, would also set the benchmark payment at the second-lowest-cost plan.[42]

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania recently studied the geographic variance in benchmarks to see what was happening in the MA plans with a greater payment from Medicare. They found greater Medicare Advantage enrollment and insurer participation in areas with higher payments. They found that the increased payment was not fully passed onto the beneficiary in the form of richer benefits but that it increased insurer participation and advertising. They concluded that “the results indicate that incidence of the subsidy falls on the supply side of the market.” In addition, “Given that MA penetration rates increase alongside reimbursements, a revealed preference argument would imply that MA is more valuable to consumers when the benchmark is higher.”[43]

What this could mean for premium support is that a more market-based benchmark could encourage greater insurer participation and thus greater market competition, leading to even higher enrollment and the potential for the more intense competition to generate even greater savings over the long term. - Build on the steady progress in risk adjustment. Risk adjustment is a tool used to address selection bias in Medicare Advantage and other private insurance programs. The goal is to mitigate an insurer’s ability to tailor plans to attract a disproportionate share of the most profitable enrollees—healthier enrollees that consume less medical services.

Every major Medicare reform proposal, based on premium support, would provide risk adjustment or significantly improve the risk-adjustment formulas or mechanisms that currently exist in the MA or Medicare Part D program. Risk adjustment could either be prospective or retrospective. Prospective risk adjustment already characterizes Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D, where government per capita payments are adjusted by demographic factors, such as age, sex, institutional or Medicaid status, and medical conditions. Retrospective risk adjustment—back-end adjustments—would be based on new pooling arrangements, such as a risk-transfer pool. In that arrangement, health plans that attracted higher-risk or more costly patients would be cross-subsidized by plans that attracted fewer high-risk or less costly patients. The value of these types of arrangements is that they would be based on hard data and not on educated guesswork or projections. The Wyden–Ryan plan, for example, includes such an approach. The Heritage proposal would include both prospective and retrospective risk adjustment.

Applying the lessons from MA’s risk-adjustment experience could mitigate the risks that only the unhealthy would be stuck in Medicare fee-for-service plans, leaving the plans’ costs to escalate and grow further away from the premium support benchmark, and thus more expensive for enrollees.

Over the past decade, as Alice Rivlin and others have noted, the risk-adjustment mechanism used in Medicare Advantage has significantly improved and succeeded in reducing favorable selection in the program. In the future, with the adoption of defined-contribution financing for the entire Medicare program, one can expect further refinements and innovative approaches to adjusting government per capita payments. One particularly interesting approach has been developed by Zhou Yang, professor of economics at Emory University. Professor Yang’s proposal, to be implemented within an environment of competitive health plans, would tie Medicare payments to positive behavioral changes: Enrollees would be rewarded for enrollment in wellness or preventive-care programs that promote a healthier (and thus less costly) lifestyle.[44]

Transitioning to Premium Support

Medicare Advantage is, in effect, a defined-contribution (premium support) program. But its flawed payment arrangement has been incompatible with efficient, and market-based, comprehensive Medicare reform. The payment changes imposed under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act are still tied to Medicare’s outdated system of administrative pricing, and they are likely to dampen the growth of enrollment, or prove to be disruptive to seniors enrolled in MA plans, as the plans adapt to the payment changes.

Medicare Advantage, as it stands today, is an imperfect program, and it must yet survive the challenges imposed upon it by the Administration and Congress who want to funnel savings from the PPACA’s payment reductions into entitlement expansions outside Medicare. Nonetheless, the program has made significant progress in delivering a wide range of integrated benefits among a variety of competing plans, including specialized health plans focused on patients with serious illnesses and disabilities. Not surprisingly, Medicare Advantage has achieved high levels of patient satisfaction, higher even than that recorded in traditional Medicare.

If structured correctly, change in the Medicare program can secure serious cost control for seniors and taxpayers alike, and ensure Medicare patients’ access to high quality care, increased provider productivity, and medical innovation. Choice and competition work in health care.[45] In the next stage of reform, Members of Congress should absorb these lessons of Medicare Advantage and build upon that progress to secure a brighter future for America’s seniors.

—Robert E. Moffit, PhD, is Senior Fellow, and Alyene Senger is a Research Associate, in the Center for Health Policy Studies, of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.