Competitive health plans provide high-quality care for some of America’s poorest and most challenging patients. Real Medicare reform based on expanded choice and competition can translate that achievement into better care for 9 million patients known as dual-eligible beneficiaries.[1] “Dual eligibles,” low-income patients covered under both Medicare and Medicaid, are an expensive and complex patient population. Nonetheless, these patients already greatly benefit from competing private health plans in Medicare Part D, the competitive prescription drug program, and Medicare Advantage, Medicare’s competitive private health insurance program. Federal policymakers can build on these successes by including these patients in a flexible Medicare defined-contribution (“premium support”) financing system where dual-eligible patients, with assistance from their families or counselors, can benefit from care coordination provided by competing health plans.

The Continuing Challenge of Dual Eligibles

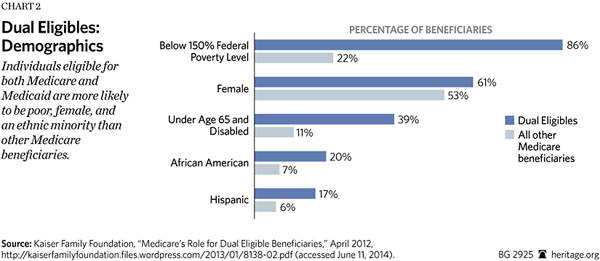

Dual eligibles are covered by both Medicare and Medicaid. They qualify for Medicare through old age or disability. Of the 7 million “full duals” who qualify for full Medicare and full Medicaid benefits, slightly more than half qualify for Medicare based on disability, not age.[2] Dual eligibles use Medicare as their primary insurance[3] to cover acute care, such as hospitalization, and post-acute care, which includes care at skilled nursing facilities for patients transitioning out of the hospital.[4] Compared to other Medicare beneficiaries, dual eligibles are disproportionately of low income, female, under the age of 65, and a racial minority.[5] More than 42 percent of dual-eligible patients represent ethnic minorities, while ethnic minorities comprise just 16 percent of the general Medicare population.[6]

Dual eligibles qualify for Medicaid on the basis of low income.[7] According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s analysis of data from 2008, 86 percent of dual eligibles had incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line[8] compared to 22 percent of all other Medicare beneficiaries.[9] A 2012 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Inspector General report found that 55 percent of dual eligibles have annual incomes lower than $10,000, compared to 6 percent of all other Medicare beneficiaries.[10] Dual eligibles use Medicaid as secondary insurance[11] to cover Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements and to cover services not offered by Medicare.[12] Medicaid benefits include long-term care, such as nursing home stays, as well as social services and dental and vision insurance.[13]

Covered under both Medicare and Medicaid, these patients are buried deep within government bureaucracy, often tangled in confusing and frustrating red tape.[14] This bureaucratic maze often leads to highly fragmented or uncoordinated care,[15] and this fragmentation directly contributes to dual eligibles’ high cost.[16]

The Cost and Complexity of the Status Quo

The status quo hurts both patients and taxpayers. The broken financing system surrounding dual eligibles increases the cost of care, highlights administrative and managerial complexities between Medicare and Medicaid, shifts costs between the two programs, and promotes inefficiencies in care delivery that harm already vulnerable patients.

High Costs. Dual-eligible patients are a heavy burden on taxpayers both at the federal level through Medicare and at the state level through Medicaid. Based on an analysis of available program data, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that in 2009 federal and state governments spent more than $250 billion on dual-eligible patients.[17] Using 2008 data, researchers for the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that dual eligibles consisted of 20 percent of the Medicare population, yet they accounted for 31 percent of all Medicare spending.[18] At a 2008 per capita cost of $14,169,[19] they were 1.8 times more expensive than other Medicare patients,[20] and they totaled $132 billion in Medicare expenditures.[21] The 2008 statistics for Medicaid are equally unbalanced. Dual eligibles made up 15 percent of the Medicaid population but amassed 39 percent of Medicaid spending.[22] Dual eligibles cost Medicaid $14,300 per capita for a cumulative expense of $128.7 billion.[23] Continuing the status quo, then, is incredibly expensive for American taxpayers.

Complex Coverage. Because Medicare is a federally administered program and Medicaid is a state-run program, the federal government and state governments both pay for dual eligibles. This fragmentation of coverage increases costs and negatively affects access and care for dual eligibles.[24]

Because Medicaid pays for Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements for dual eligibles, states often lower their Medicaid reimbursement levels for providers, which means that dual-eligible patients cannot afford their copayments and thus have fewer physician visits.[25] Where Medicare and Medicaid cover similar services, such as home health care, state Medicaid policies make Medicare the primary payer of home health services wherever possible, a strategy known as “Medicare maximization.”[26] “Medicare maximization” also causes states to limit their home-based and community-based benefits to keep more people off Medicaid and push them toward services that Medicare covers.[27] Whether, in any given instance, Medicare or Medicaid coverage is best for a patient is debatable, but the shunting from one program to another incurs administrative costs. While state governments can save money, this intergovernmental cost shifting obviously does nothing to reduce the overall burdens on taxpayers.

Cost Shifting. This fragmentation also distorts the incentives of those caring for the one in seven dual eligibles living in long-term facilities.[28] In nursing homes, for example, financial incentives encourage re-hospitalization. After a three-day hospital stay, Medicare’s skilled-nursing benefit restarts, and it reimburses at a higher level than Medicaid.[29] Nursing homes thus can increase their revenues by readmitting residents to the hospital. While the nursing home resident is hospitalized, some nursing homes take advantage of Medicaid’s bed-hold policy where the state Medicaid program pays the nursing home to reserve the bed of a resident receiving acute care.[30] If a state’s Medicaid bed-hold reimbursement is higher than its long-term care payment, nursing homes are incentivized to hospitalize their residents and collect the bed-hold reimbursement. In states with bed-hold policies, the odds of hospitalization were 36 percent higher than in states without the policy.[31] Therefore, fragmented coverage between Medicare and Medicaid incentivizes some nursing homes to send patients back to the hospital, collect Medicaid’s bed-hold reimbursement, and readmit the patient to their facility to receive Medicare’s skilled-nursing benefit.

Taxpayers pay a high price for these distorted economic incentives because hospital treatment normally costs more than nursing home treatment. In fact, roughly one in four nursing home residents is hospitalized annually despite research showing that they could be treated in the nursing home for less money.[32] Research showed that hospital treatment for nursing home residents in Missouri for lower respiratory infections, such as pneumonia and bronchitis, cost $419.75, while the mean daily cost was $138.24 for the nursing home treatment.[33]

Cost shifting occurs among younger dual eligibles, too. Dartmouth researchers examining Medicare and Medicaid spending on dual eligibles under the age of 65 confirmed that states with higher levels of Medicaid spending had lower levels of Medicare spending; on the other hand, states with higher levels of Medicare spending had lower levels of Medicaid expenditures.[34] In other words, Medicare and Medicaid simply pass the buck to one another, leaving the patient and the taxpayer to absorb the consequences.

Lack of Care Coordination. These distorted incentives undercut care coordination. That would be expected, of course, since two different government programs operating with separate budgets are covering the same patients. Urban Institute researchers Lisa Clemans-Cope and Timothy Waidmann observe in The New England Journal of Medicine that the disjointed Medicare and Medicaid structure that serves dual eligibles provides little incentive to coordinate primary care and long-term care and supports that could reduce hospitalization.[35] Under the current system, the savings for the federal government under Medicare normally mean higher costs for state governments through Medicaid.[36] Thus, despite the high cost and the negative health consequences, neither program actively coordinates the care that patients receive under both programs.

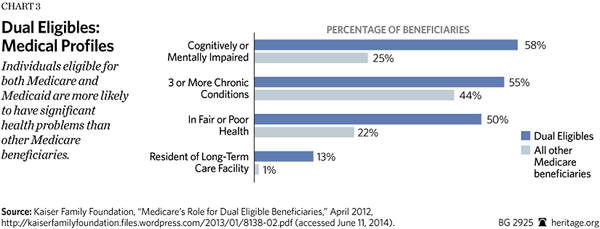

Diversity of Medical Conditions. The fragmentation of coverage and lack of care coordination are even more problematic in light of dual eligibles’ health status. Half of dual eligibles rate their health as fair or poor, as opposed to 22 percent of all other Medicare beneficiaries.[37] Available data confirms dual eligibles’ self-assessment. Researchers with the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that 55 percent of dual eligibles in 2008 had three or more chronic medical conditions;[38] these chronic conditions often overlap and include diabetes, pulmonary disease, and strokes.[39] Mental challenges were also common. Fifty-eight percent of dual eligibles had a cognitive or mental impairment.[40] When compared to non-dual-eligible Medicare recipients, dual eligibles were also more likely to be frail.[41]

The confluence of these conditions creates a “perfect health care storm” for dual eligibles. Cumulatively, dual eligibles are less healthy than the remainder of the Medicare population; they are twice as likely to die over the course of the year as other Medicare recipients.[42] Dual eligibles’ poor health likely augments the difficulties they experience through fragmented care in long-term care facilities like nursing homes. In 2008, for example, dual eligibles living in long-term care facilities had a 20 percent higher mortality rate than dual eligibles living in the community.[43]

Despite their generally high level of medical needs, dual eligibles differ significantly from one another. Based on 2008 data, 39 percent of duals were under 65 and disabled.[44] The high prevalence of both elderly patients and those who are young and disabled is one of the central challenges that dual-eligible patients present to policymakers: how to design and implement a policy that allows enough flexibility in financing and care delivery to meet such diverse patient needs. Because so many dual eligibles differ from one another significantly, the CBO doubts that a one-size-fits-all approach can be effective.[45]

Dual Eligibles and Private Health Plans

Despite the social and medical challenges these patients present, two competitive Medicare programs serve dual eligibles well. Medicare Part D, the prescription drug program, covers dual eligibles’ prescription drug benefit and allows Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in private plans that deliver a wide variety of drug therapies. Medicare Advantage (MA), also known as Medicare Part C, lets Medicare beneficiaries enroll in private health insurance plans instead of traditional Medicare, and the federal government makes a defined contribution to the plan of the enrollees’ choice. Through MA, dual-eligible patients also have private plans designed specifically for them called Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs). D-SNPs’ care coordination models appear to offer the most promising approaches to improving care and reducing costs for dual eligibles.

Medicare Part D. Under the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, Congress shifted the source of drug coverage for dual eligibles from Medicaid to Medicare Part D.[46] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services randomly assigns dual eligibles to private prescription drug plans unless they have elected a specific Part D plan or have opted out of Part D prescription drug coverage.[47] Dual-eligible beneficiaries are also automatically eligible for the low-income subsidy program that helps with Part D premiums and cost sharing.[48]

The Part D program protects low-income enrollees from high out-of-pocket costs, while ensuring access to critical drugs. The Health and Human Services Inspector General issued a 2012 report that found that Part D plan formularies, the preferred drug lists of private health plans, on average included 96 percent of the 191 drugs most commonly used by dual-eligible patients.[49] This finding reinforced a 2008 Inspector General finding: 93 percent of nursing home administrators reported that their dual-eligible residents were receiving all necessary Part D drugs.[50]

Because of its success in limiting dual eligibles’ out-of-pocket drug costs while providing broad access to the vast majority of their prescription drugs, Medicare Part D is highly popular among these patients. A 2013 KRC Research survey found a 96 percent satisfaction rate among dual eligibles with the Medicare Part D drug program.[51]

Concern remains over adding a universal drug benefit to an insolvent Medicare program, but the design of Medicare Part D is an example of successful market-based defined-contribution program. In Medicare Part D, private plans compete directly for beneficiaries’ dollars in the competitive marketplace. The intensity of competition has contributed to lower than expected costs. By 2013, Medicare Part D had beaten original cost projections by $194 billion, meaning actual costs were more than 35 percent lower than they were projected to be at the inception of the program.[52] Because lower drug costs and affordable premiums resulted from intense competition—not from the price controls that characterize the bulk of the Medicare program—the program has not deterred drug companies from continuing to invest money in research and development initiatives.[53]

Medicare Advantage/Special Need Plans. In addition to providing dual eligibles’ drug coverage through Medicare Part D, the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 created the Medicare Advantage program, a system of competing private health plans through which beneficiaries choose private health coverage in lieu of traditional Medicare. MA enrollment has climbed steadily and reached 30 percent of all Medicare enrollees in 2014.[54] Among the offerings in the MA menu are special needs plans (SNPs). SNPs are private health plans offered through MA that limit membership to people with specific diseases or characteristics and tailor their benefits, provider choices, and drug formularies to best meet those patients’ needs.[55] SNPs cover all medically necessary and preventive services offered through Medicare Part A and Medicare Part B as well as prescription drug coverage under Part D.[56] All Medicare Advantage plans, including SNPs, limit enrollees’ out-of-pocket expenses.[57]

As of 2012, 20 percent of all dual eligibles were enrolled in D-SNPs, while 80 percent were still enrolled in traditional Medicare.[58] In 2014, over 1.5 million dual eligibles are enrolled in D-SNPs, more than triple the number of dual eligibles enrolled in D-SNPs in 2006.[59] Geographically, access to these special plans is also improving; 82 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in 2013 lived in an area where D-SNPs serve dual-eligible patients, an increase from 78 percent in 2012.[60]

D-SNPs’ Successes. Some SNPs use a care coordinator to monitor patients’ health, help patients access community resources, and coordinate Medicare and Medicaid services.[61] Integrated and coordinated-care D-SNPs that allow private health insurance companies to integrate Medicare and Medicaid benefits into one plan offer examples of ways to overcome cost shifting and improve care for dual eligibles. Avalere Health’s 2012 study of Mercy Care Plan in Arizona found that 3 percent more dual eligibles enrolled in this coordinated care plan used preventive and out-patient services; enrollees also had a 31 percent lower discharge rate, 43 percent lower rate of days spent in the hospital, 19 percent lower average length of stay, 9 percent lower rate of emergency visits, and a 21 percent lower readmission rate than dual eligibles nationwide who are enrolled in traditional Medicare.[62] The bottom line: This coordinated, integrated care model kept enrollees out of the hospital and produced fewer readmissions than traditional Medicare coverage.[63]

Other coordinated care models have produced similar positive results. Researchers studying SCAN Health Plan’s integrated care model available through MA to dual eligibles in California found that among the plan’s 5,500 dual enrollees were 25 percent fewer hospital readmissions than traditional Medicare.[64] Other findings were also impressive, including a 40 percent lower initial hospitalization and readmission rate for pneumonia, 29 percent better performance in diabetes care, and 25 percent better performance in neurological disorder assessments.[65] These fewer hospitalizations and readmissions could lead to annual cost savings of $50 million if adopted more broadly in California’s dual-eligible population.[66]

In Massachusetts, the MassHealth Senior Care Options program, an integrated managed care program, likewise achieved excellent outcomes among its elderly dual enrollees. It lowered enrollees’ nursing home usage and kept frail enrollees in the community and out of nursing homes for longer periods of time than the state averages for beneficiaries receiving traditional Medicare and Medicaid coverage.[67] The success of coordinated-care models in Arizona, California, and Massachusetts all suggest that integrated care D-SNPs can improve dual eligibles’ health outcomes and help direct dual eligibles to more appropriate, less costly care settings.

There is little doubt that these impressive improvements in care coordination could reduce overall health care costs if they were widely adopted, but the approach particularly helps patients with multiple chronic disorders who may also lack strong social support structures, which is the case for many dual eligibles. Care-coordination models for dual eligibles could save Medicare $125 billion and Medicaid $34 billion over 10 years according to health policy specialist and Emory University Professor Kenneth Thorpe.[68]

Real Reform: Building on Medicare’s Successes

The problem with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s approach to dual eligibles is that it does not fix the fragmented care that duals experience between Medicare and Medicaid. Rather than pushing dual eligibles deeper into state-managed Medicaid programs,[69] Congress should build upon the evident progress and success of competitive private health plans that are already serving dual-eligible patients in the Medicare program.

Medicare, a complex fee-for-service system, is long overdue for serious structural reform. The most promising approach to that reform builds upon the financing systems for Medicare Part D and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program.[70] Those financing systems are defined-contribution (“premium support”) arrangements in which the government makes a direct contribution to the plan of an enrollee’s choice, and health plans compete on a level playing field to provide a guaranteed set of benefits.

This approach to Medicare reform enjoys broad support. Beyond The Heritage Foundation’s detailed proposal[71] for the design and implementation of such a system, analysts at the American Enterprise Institute, the Brookings Institution, and the Progressive Policy Institute, as well as former Directors of the Congressional Budget Office Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Alice Rivlin all support such reform. This approach is also embodied in congressional proposals developed by Representative Paul Ryan (R–WI) and the House Budget Committee, Senator Ron Wyden (D–OR), Senator Tom Coburn (R–OK), and Senator Richard Burr (R–NC), among others.[72]

Premium Support and Dual Eligibles. Premium support would use a system of market-based bidding among regionally competing plans to determine the federal government’s defined contribution, which is what occurs today in Medicare Part D. The government’s contribution would reflect real market conditions rather than administrative determinations often disconnected from the real conditions of supply and demand. That payment would then be assigned to the private plan of the beneficiary’s choosing.

Beyond the standard Medicare payment, several premium support proposals would use Medicaid financing as supplemental assistance for the dual-eligible population. In fact, all major Medicare premium support reform plans either maintain or enhance existing financial assistance for low-income Medicare beneficiaries, including dual eligibles.[73] While these reforms would expand beneficiaries’ choices of private plans, all beneficiaries, including dual eligibles, could also choose to remain with traditional Medicare. In a properly designed new competitive system, D-SNPs as well as other newly emerging health plans would compete directly for dual eligibles’ dollars on the basis of access to quality medical care, performance, and price.[74] Using broadly available information on health results, dual-eligible patients, with the assistance of their loved ones or counselors, would be able to enroll in integrated coordinated-care plans. This would enable these patients to secure the best available care delivery options and achieve better health outcomes.

Under a reformed Medicare program, policymakers would streamline the interaction between Medicare and Medicaid, and dual eligibles would escape the structural deficiencies of a disjointed system and a broken incentive structure. For example, dual-eligible beneficiaries enrolled in competing private plans could get supplementary assistance from their state officials who could “top up” the federal government’s defined contribution with Medicaid funds toward the cost of their private health plan.[75]

Ultimately, dual eligibles would greatly benefit from the diversity of competing plans and delivery options under a flexible premium support system. Private coordinated-care plans can provide care managers to guide dual eligibles through the care cycle, including the provision of long-term care supports and services. In Medicare Advantage today, according to MedPAC, 19 percent of D-SNPs integrate long-term care supports and services with their acute care benefits either directly through the D-SNP or through a Medicaid-funded managed-care organization.[76]

An open and competitive Medicare system also would create opportunities for more care innovations that can lead to better care for dual eligibles. In the same way that Medicare Advantage and the creation of D-SNPs has spurred innovation in care delivery for dual eligibles, direct competition between traditional Medicare and the next generation of private plans, as authorized under Medicare premium support reform, could take care delivery to the next level. As David Goldhill, a prominent business leader, has observed, “Successful new ideas require an environment that allows innovators to try out new business models, new approaches to pricing, and new definitions and bundles of services. Government policy is a tidal wave in the opposite direction—toward uniformity, defined ‘minimums,’ and equal access. Each policy and each rule may sound sensible in a vacuum, but collectively they make it very difficult for the truly transformative ideas to rise to the surface and effect real change.”[77]

A Medicare premium support program can create an environment that instead stimulates such transformative change. Competitive plans providing integrated care could compete on the provision of superior health outcomes, which would incentivize insurers to incorporate the latest advances in personalized medicine, genetic profiling, and biopharmaceutical innovations for a patient population struggling with chronic illnesses. Price competition would promote cost-saving innovations in care delivery, including care for the challenging and diverse dual-eligible population.[78] Plans could further specialize in the provision of different levels of care, such as dividing D-SNPs between plans designed for younger, disabled dual-eligible patients and others for older dual eligibles since their needs are often quite different. Plans could offer supplementary options that tailor coverage to beneficiaries’ particular needs in similar ways to how D-SNPs currently allow dual eligibles to forgo certain supplementary benefits in some areas in favor of more supplementary coverage in other areas that matter to them, such as vision, prevention, or dental care.[79]

While the CBO confirms that a Medicare premium support system would benefit beneficiaries and taxpayers alike,[80] the reform also offers new opportunities for D-SNP coordinated-care plans to overcome bureaucratic cost shifting and enable dual eligibles to take advantage of lower-cost, more effective care settings. Instead of Washington’s tiresome one-size-fits-all approach,[81] federal policy can simultaneously promote choice, better health, and real cost savings.

Conclusion

Dual eligibles present unique policy challenges given their high cost and complex medical issues. The current fractured incentive structure increases the cost of care while promoting poor health for some of the most vulnerable Americans.

A better way is possible. Building on dual eligibles’ positive experiences with competitive Medicare programs, dual-eligible beneficiaries could greatly benefit from private D-SNPs and other emerging plans offering coordinated care within a Medicare defined-contribution system. Federal policymakers should enable plans to tailor their benefit offerings to all Medicare beneficiaries, including dual eligibles. These patient-centered, market-based health reforms can help to heal the fractured incentive structure surrounding dual eligibles, improve dual eligibles’ health, and save taxpayers’ money.

—Jonathan Crowe is a Graduate Health Policy Fellow in the Center for Health Policy Studies, of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.