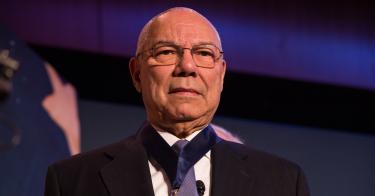

America lost a great man this week. Colin Powell, the first African American to become both the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the secretary of state, died at the age of 84.

A man of character by all accounts and a leader in every sense of the word, Powell was born of immigrant parents in Harlem, New York. After his commission in the Army, Powell was selected for one of the world’s most challenging team leadership courses and what he described as the ultimate physical and mental test—Army Ranger training at Fort Benning, Georgia.

The first of his two tours in Vietnam followed not long after. For the better part of a year, he served as the lone U.S. adviser to a battalion within the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. In that role, he was directly involved with that unit’s every firefight, ambush, and counterinsurgency operation. Powell was a warrior.

As a staff officer, his second tour in Vietnam should have been far less hazardous, but as fate would have it, the helicopter carrying Powell and his boss crashed enroute to a recently captured North Vietnamese base. He suffered a fractured ankle on impact, but managed to pull his boss from the wreckage and then helped extract three others to safety. Powell wasn’t fearless—as he said himself, he moved in spite of his fears.

His assignments within the Army grew in both responsibility and notoriety, until he was pulled up out of the service to become President Ronald Reagan’s national security adviser in 1987. While a prestigious role in and of itself, that position led to his promotion to the rank of a four-star general and his selection and confirmation as the youngest chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in our nation’s history just two years later.

Powell held the role of chairman through Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. Without question, the advice and support he offered were instrumental to the success our nation enjoyed in those operations.

The general retired from the service in 1993, but he was called on to serve our nation again during a period of conflict just eight years later, this last time as the secretary of state. In this role, he helped assemble a coalition of nations to fight what would become known as the global war on terror.

While the secretary’s actions as a statesman are well documented, what he did as a leader within the State Department is not.

Many organizations in Washington are comprised of incredibly talented people, leading many principals to believe their teams can run well on their own. That is especially true with government agencies and departments where leaders all too often focus their attention and efforts outside their organization, leaving the team behind them to its own devices while they meet the demands from on high.

As a wartime secretary, it would have been easy for Powell to have taken the same approach that many other secretaries of state have taken, and yet he chose the more difficult path.

He executed his role as a diplomat to the same level of excellence he had known throughout his life, while holding on to the “follow me” ideal he taken on at Fort Benning—an ideal he went on to ingrain at every level within that State Department.

As you might imagine, he thought a lot about leadership and spoke frequently on its importance for the rest of his life and, at the end of the day, he defined leadership as getting people to do more than the science of management says is possible.

Boiling such an important topic down to a single powerful line would stymie the best of writers or leaders, but it was easy for Colin Powell. Maybe that’s because, out of such humble beginnings, he did the same thing with his own life. And what an incredible life it was.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal