Abstract: While by no means the biggest of the tax increases included in the pending health care legislation, the Senate health insurance premium tax illustrates much of what is wrong with the Obama-Reid-Pelosi approach to health reform. Rather than actually reforming and reducing the costs of the world's most expensive health system, the Senate and House health care bills would drive America's health care costs even higher through a combination of massive new federal spending, taxation, and regulation. Congress should scrap the Senate health insurance premium tax, along with most of the rest of the House and Senate bills, and start over with a better, more focused design for genuine health reform.

Among the various new taxes in the Senate health care legislation is one disguised as a $6.7 billion a year "fee" imposed on health insurers.[1] In reality, this "fee" is structured as an insurance premium tax that will be passed directly on to consumers. If enacted, it would add an average of 1.5 percent to the cost of health insurance policies currently purchased by over 165 million Americans, starting in 2010.

While it is true that the cost to individuals and families of this new premium tax would be less than that of some other tax increases in the Senate bill, it is significant for more than just its cost. More important, this provision of the Senate bill encapsulates in microcosm virtually all of the larger, fundamental problems with the Obama-Reid-Pelosi approach to so-called health reform--problems that are endemic to both the House and Senate bills. Specifically:

- It increases health costs. This so-called fee on insurance companies would be passed on to consumers, directly increasing the cost of health insurance for tens of millions of Americans and contravening Congress's stated intention that its legislation will reduce health insurance costs.

- It increases taxes. Because this "fee" is effectively an insurance premium tax imposed on policies purchased by half of all Americans, it violates President Barack Obama's repeated promise that most Americans, or at least those with incomes below $250,000, would not see their taxes increased in any way, shape, or form.

- It creates new inequities. Because it would apply to policies purchased from insurers but not to employer self-insured health plans, this insurance premium tax would create new inequities by disadvantaging one source of health insurance coverage relative to another source of coverage, thus creating winners and losers based on where people happen to work.

- It is disingenuous. Labeling these provisions a "fee" imposed on insurance companies is designed to give the impression that it affects only a politically disfavored interest group. In reality, however, since the legislation specifies that it will be apportioned based on each insurer's premium revenues, it would function exactly like a direct insurance premium tax paid by consumers.

- It creates perverse incentives. This tax would apply to those who have purchased health insurance, with the proceeds funding subsidies for those who have not purchased such coverage.

- It distorts markets. The tax would apply to both an insurance company's premium revenue and its revenue from providing "administrative services" (such as claims processing) to employer and union self-insured plans. However, a vendor that provides self-insured plans with administrative services but does not sell health insurance would not be subject to the tax. Thus, self-insured employers would have a financial incentive to prefer "third-party administrators" that are not insurance companies when contracting for administrative services for their plans.

- It expands federal power. This insurance premium tax would create a new, permanent federal tax that could, and likely would, be increased by Congress in future years as the growth in new government spending in the legislation outstrips the growth of revenues to fund that spending.

How the New Premium Tax Works

The Senate bill's new premium tax is separate from, and in addition to, another new excise tax that would be imposed on "high-cost" health plans. The excise tax on high-cost plans is larger, has received more attention, and would apply to all private insurance plans, both those sold by insurers and employer-sponsored self-insured plans.

In contrast, the premium tax takes the form of a $6.7 billion per year "fee" imposed on both for-profit and not-for-profit commercial insurers, but not on employer-sponsored self-insured plans, and would apply to all commercial health insurance policies, not just those that are high-cost. While the provision is described as a fee, it is designed to function like an insurance premium tax and would work as follows:

- Each year, the U.S. Treasury would calculate the total amount of premiums received in the previous year by all private insurers in the U.S. for the health insurance policies they sold, as well as the insurers' revenues from providing administrative services to employer and union self-insured plans.

- The Treasury would then charge each insurer a portion of the $6.7 billion tax based on each insurer's share of total premiums plus revenues from providing administrative services.

- In calculating the tax, the legislation instructs the Treasury to double the amount of insurer income from providing administrative services before adding it to the premium income and then to apportion the tax based on each insurer's share of the combined, total amount.

Within the broad category of "health insurance" there are different "lines" of business, such as individual policies; employer group policies; limited-benefit policies for dental care, vision care, and pharmaceutical benefits (such as the private plans that provide Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage); and reinsurance and stop-loss coverage sold to employer and union self-insured plans. Some insurers specialize in just one or two lines of coverage, while others offer a broad range of products. Given that the new tax would be assessed based on each insurer's market share of total health insurance premiums and the legislative specifics of how it would be applied, it is possible to predict a number of effects.

First, the legislation specifies that employer self-insured plans and government health care programs are exempt but that all commercial health insurance lines are subject to the tax, including private plans purchased with government subsidies, so traditional Medicaid and Medicare coverage will not be taxed. However, Medicare Advantage plans, Medicare Prescription Drug plans, and any Medicaid HMO coverage for which a state contracts with an insurer on an "at-risk" basis will be subject to the tax. Also subject to the tax will be the private insurance plans purchased by federal workers through the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP).

Second, it can be expected that insurers will not want to disadvantage some customers relative to other customers. Consequently, insurers offering more than one line of health insurance can be expected to pass on the cost of the tax proportionately to each line of business, according to the premium revenues they receive from each. For example, an insurer whose premium revenues come 75 percent from group policies and 25 percent from individual policies can be expected to pass on to its group policyholders 75 percent of what the insurer is assessed under the new tax while passing on the other 25 percent of the tax to its individual policyholders.

Third, it can be expected that the tax will also be passed on proportionately at the customer and enrollee level. Thus, individuals and groups that pay more for health insurance, either because they have policies with more benefits or because they have higher medical costs, will pay more of the tax. In the same fashion, individuals who, for example, buy more gasoline pay a larger share of total gas taxes than those who buy less gasoline.

How the Tax Will Affect Families and Businesses

Estimated Individual and Family Costs. The cost of this tax to individuals and families can be calculated from recent health insurance premium and enrollment data by product line. In 2008, all private insurers in the U.S. received a combined $446.5 billion in health insurance premiums. Thus, assessing a $6.7 billion annual fee on that current level of total premiums translates into an effective premium tax of 1.5 percent on every commercial health insurance policy.[2]

Premium and enrollment data are available for seven health insurance product lines: individual, group, FEHBP, Medicare Advantage, Medicaid Managed Care, Medicare Supplemental (Medigap), and limited-benefit plans. Thus, the per-capita amount of the tax can be further estimated for each type of health insurance coverage.

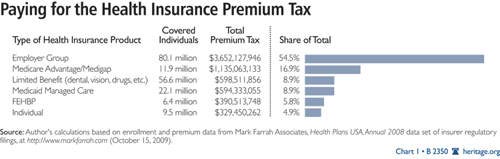

Small Business to Pay the Largest Share. Chart 1 shows that over half of the tax will be paid by workers and dependents covered by employer group policies. Furthermore, because most large employers self-insure their health benefit plans, the group coverage portion of this premium tax will fall disproportionately on small and medium-size businesses. Employer survey data from 2008 indicate that 88 percent of workers in firms with three to 199 employees were in fully insured plans, while 89 percent of workers employed in firms with 5,000 or more employees were in self-insured plans.[3]

Table 1 shows the estimated average national amounts for the premium tax by insurance product line. On average, the premium tax will increase the cost of health insurance $35 per person per year (or $140 per year for a family of four) for those with individual coverage; $46 per person per year (or $184 per year for a family of four) for those with employer group coverage; and $61 per person per year (or $244 per year for a family of four) for federal workers and their dependents with coverage through the FEHBP.

These differing amounts are explained by differences in the scope of the coverage purchased, the health risks of the individuals covered, and geographic variations in the costs of medical care. Thus, while all three subsets of customers are buying what is commonly known as major medical coverage, federal workers would pay more in premium taxes than those with individual or small group coverage because they pay higher than average premiums for coverage.

The higher premiums in the FEHBP are, in turn, attributable to the fact that the average age of the federal workforce is higher than that of the civilian workforce, a larger share of federal workers reside in places with higher than average medical costs, and federal workers tend to choose plans with more comprehensive coverage relative to the plans purchased by the self-employed or small private businesses. Similarly, the per-capita tax amounts are somewhat higher for private employer group coverage than they are for individual coverage because businesses tend to offer their workers plans with more benefits and lower co-pays relative to the plans typically purchased by self-employed individuals buying coverage in the individual market.

Costs to Seniors. About one-fourth of the elderly with Medicare coverage get their benefits through a Medicare Advantage plan offered by a private insurer. Medicare Advantage plans are particularly popular with lower-income seniors because they often have much lower co-pays and deductibles than traditional Medicare. As shown in Table 1, the Senate health insurance premium tax would increase the cost of Medicare Advantage coverage by an average of $131 per beneficiary ($262 per elderly couple) per year.

For seniors who remain in traditional Medicare but purchase their own private Medicare Supplemental (commonly called Medigap) policies tocover all or part of Medicare's deductibles and coinsurance, the Senate health insurance premium tax would increase the cost of their Medigap coverage by $28 ($56 per elderly couple) per year.

Thus, through either Medicare Advantage or Medigap, seniors would pay approximately 17 percent of the new premium tax--the second largest share after small business. (See Chart 1.)

Conclusion

While by no means the biggest of the tax increases included in the pending health care legislation, the Senate health insurance premium tax illustrates much of what is wrong with the Obama-Reid-Pelosi approach to health reform. Rather than actually reforming and reducing the costs of the world's most expensive health system, the Senate and House health care bills would drive America's health care costs even higher through a combination of massive new federal spending, taxation, and regulation.

Furthermore, the Senate health insurance premium tax is just one more example of how the legislation would impose new costs--starting next year--on Americans who already have health insurance coverage while deferring for three or four years the even larger amounts that Congress proposes to spend subsidizing those without coverage.

The Senate health insurance premium tax encapsulates in microcosm how the Obama Administration and the current Congress have managed to turn the worthwhile and widely supported goal of reforming America's health system to lower costs, expand coverage, and provide better value into a colossal legislative nightmare of increased taxing, spending, and regulatory micromanagement by the federal government.

Congress should scrap the Senate health insurance premium tax, along with most of the rest of the House and Senate bills, and start over with a better, more focused design for genuine health reform.

Edmund F. Haislmaier is Senior Research Fellow in the Center for Health Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation.