Abstract: Many retired Americans believe that they have already paid for their Medicare benefits. Their benefits, though, are not funded by the payroll taxes they paid during their working years—but mostly by payroll tax revenues from current workers. As a result, the Medicare program faces huge structural deficits, and seniors face automatic benefit reductions in 2024—or working Americans will shoulder enormous tax increases—if reforms are not enacted. Medicare should move to a premium support model, and Congress must direct Medicare’s limited financial resources at those who need them most. Otherwise, Medicare’s current course is set for disaster. It is still possible to reverse this course, yet Congress must pursue rational reforms quickly.

The case for Medicare reform is overwhelming. Medicare faces huge structural deficits, and if effective solutions to control its costs are not implemented, seniors will face automatic benefit reductions when the Medicare Part A Trust Fund becomes insolvent in 2024, or working Americans will be required to pay much higher taxes to keep the broken program afloat.

Neither of these outcomes is inevitable. The right reform: moving Medicare to a “premium support” model—which would provide government health care assistance for seniors through a defined contribution—to harness the benefits of choice and competition. Such a reform would create a competitive marketplace in which seniors can choose among competing plans offering Medicare benefits. This reform will secure better value for seniors by driving down the cost of health care delivery without sacrificing its quality.

Financing Medicare through premium support is necessary, but insufficient. Congress must also re-target limited financial resources to those who need them most. This means continuing and expanding income adjustment (also called means testing), which would reduce the amount of federal assistance that wealthier beneficiaries received for their health care benefits, based on their retirement income. In the face of dangerous deficits, it is no longer viable to perpetuate a wildly unaffordable universal entitlement program.

Income adjustment is already Medicare policy. Further changes made under Obamacare, however, are crude and unnecessarily punitive. Income adjustment should be done in a fairer, more gradual, less disruptive and more transparent manner. The Heritage Foundation proposes just such a change with its premium support model.[1]

The Problem: Taxpayers Can’t Afford Universal Subsidies

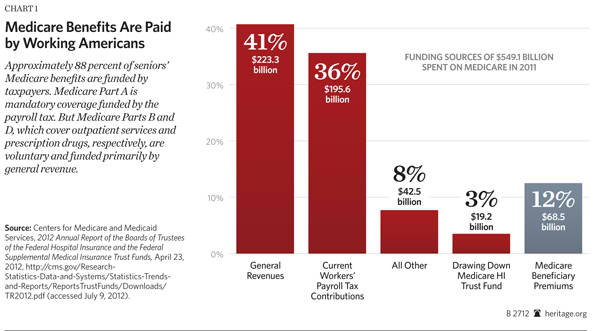

Too many retired Americans think that they have already paid for their Medicare benefits. But the benefits of today’s Medicare recipients are not funded by the payroll taxes they paid during their working years—they are funded primarily by payroll tax revenue from current workers. Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that the payroll tax funds just one part of Medicare: the hospitalization insurance provided under Part A. Other coverage under Medicare is funded primarily from general revenues. In fact, 41 percent of funding for the entire Medicare program comes from general revenues.[2]

As Heritage Foundation economic expert J. D. Foster explains, these general revenue funds represent a subsidy.[3] Rather than eliminating the general revenue subsidy to relieve Medicare’s shortfall, Foster argues that the problem can be fixed by adjusting the criteria for who receives Medicare subsidies, and how much, based on need as reflected by income.

The Solution: Updating and Improving Income Adjustment

Income adjustment already exists in Medicare today. In Parts B and D, which respectively cover outpatient and physician services and prescription drugs, seniors pay a standard premium, and the wealthy—individuals earning $85,000 or more and couples earning $170,000 or more—pay higher premiums. Higher income-related premiums were added to Part B under the Medicare Modernization Act signed into law by President George W. Bush. Obamacare added income-related premiums to Part D and expanded those in Part B. The income thresholds under Obamacare, however, are not indexed for inflation and therefore cause more seniors to pay more every year.

Moreover, in both cases, the policy was not intended to strengthen Medicare by reducing its shortfall. Instead, income-related premiums were introduced as part of legislation that increased government spending. Taxpayers cannot afford Congress repeating this mistake.

Bipartisan support for further income adjusting of Medicare is already emerging. House Republicans and President Barack Obama favor raising income-related premiums further and the number of enrollees who pay them.[4] Expanding income adjustment in Medicare is thus not only likely, but also necessary in order to sustain the program for future generations. Increasing the premiums that the wealthy pay under the current Medicare program is inarguably sound policy, and it can be significantly improved if included as part of broader structural reforms that move Medicare to a premium support model.

Time to Rethink Medicare’s Core Objectives

Circumstances have changed since the 1960s when Medicare was created. In 1970, 20.4 million seniors were enrolled in the Medicare program, and its annual cost was $7.5 billion.[5] By 2011, enrollment had more than doubled to almost 49 million, and the program’s cost grew to $549 billion.[6] By 2021, Medicare will cover close to 66 million Americans and consume $1 trillion.[7] Its 75-year projections show over $37 trillion in unfunded obligations. Clearly, the program is on an unaffordable path.

The Folly of Universal Entitlements. Congress has proved that it cannot continue a universal entitlement like Medicare and serve as a good steward of taxpayer dollars. Instead, congressional spending has made a wreckage of the nation’s finances, and its multiple attempts to rein in Medicare spending through price controls and micromanagement have distorted incentives in the health care system.[8]

The American public supports providing a safety net for citizens in need, but providing health and retirement income benefits for all, unrelated to need or the size of their income, does not fulfill that purpose. Instead, it threatens the very existence of such a concept—and in practice, achieves the opposite—by failing to provide adequate protection for all. As The Heritage Foundation’s Stuart Butler and the New America Foundation’s Maya MacGuineas explain, the universality of entitlements “means that resources are directed to the affluent, leaving less than is adequate for those in need. Bill Gates will qualify for subsidized benefits under Medicare, while other future retirees will be unable to afford the program’s deductibles and co-payments.”[9]

Remarkably, the net federal transfer of wealth in the Medicare program has flowed from lower-income to higher-income enrollees. According to a 1997 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, wealthy beneficiaries consumed significantly more Medicare spending due to the fact that they generally have higher expenditures and live longer.[10] Even though the structure of the Medicare payroll tax means that high earners pay more into the program overall, “the income-related differences in lifetime expenditures exceed the income-related differences in lifetime taxes: intra-generational transfers are largely from lower-income to higher-income households.”[11]

More recent research by the Congressional Budget Office shows that total federal transfer payments to the wealthy, which amount to more than $10 billion each year, stem primarily from Social Security and Medicare. But the pattern of these transfers has contributed to the increase in uneven distribution of income over the past several decades.[12] Transfer payments favor the more affluent; in 1979, the bottom 50 percent of all earners received more than 50 percent of federal transfer payments, whereas in 2007, they received about 35 percent.

Why the Wealthy Should Pay More. According to the Social Security Administration, “The elderly (persons aged 65 or older) are financially better off today than ever before.”[13] Since Medicare started in 1965, seniors’ incomes have increased across the board. In 1970, the median household income for those 65 and older was $17,528 (in 2010 dollars). In 2010, it had increased to $31,408.[14] Fewer seniors are living in or near poverty; while in 1996, 28.5 percent of those ages 65 and above lived below poverty, by 2010 it had fallen to 9 percent.[15] As individuals enter retirement with higher incomes, the wealthy can and should devote a larger portion of their income to health care.

Since health care costs are growing faster than inflation, seniors’ health spending as a portion of their income is also growing. In 2006, beneficiaries’ median out-of-pocket health care spending represented 16.2 percent of their income. The burden was larger for seniors living in or near poverty, increasing to 22.9 percent for those between 100 percent and 199 percent of the federal poverty line. Meanwhile, seniors living above 400 percent of the federal poverty line spent just 8.2 percent of their income on out-of-pocket health care costs.[16]

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, “The burden of health care costs in the future is likely to continue being considerably greater for certain subgroups of the Medicare population—particularly those with low incomes who are not covered by Medicaid, the oldest old [sic], and beneficiaries who have significant medical needs that are not fully met by Medicare-covered benefits.”[17] This outcome can be averted by combining income adjustment with market-driven reform that improves the value of the program.

The Least Fair Option, Except for All the Others. The facts are simple. Younger workers pay for the Medicare benefits of today’s seniors. But they have little guarantee that the program will even exist when they retire. At the same time, seniors currently use health benefits worth much more than what they paid into the system when they were working. This is a long-enduring trend that will continue for future enrollees.[18] Thus, the status quo, marked by rapidly increasing spending and borrowing, threatens the viability of Medicare for tomorrow’s seniors.

The massive accumulation of federal debt also harms the ability of younger workers and their families to adequately prepare financially for their own retirement. Massive entitlement spending is one of the main reasons that publicly held debt will exceed 90 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of this decade. History shows that at this point, economic growth falters significantly, which in turn delays the age at which young adults can begin to save and invest.[19]

Members of Congress who try to maintain the status quo are making false promises to the American public. Congress can perhaps keep its promises to some seniors right now. Others—perhaps even those entering Medicare now—will by necessity receive less than they have been promised—regardless of their level of need.

So, the real policy issue is not what is most fair relative to the Medicare program of the past, but what is the most fair and equitable option for moving forward in a necessary environment of fiscal restraint. Rather than requiring younger generations to carry the burden alone, Medicare reform should protect the safety net for those who have the most financial need, now and in the future. This will allow Washington to make a promise it can keep: that all seniors, regardless of income or health status, will have access to adequate, affordable health coverage.

True Social Insurance. Some Americans think that since they have paid into the system, they are entitled to receive something back. But this is not how insurance works. True insurance means that Americans pay in for protection, in this case from health care costs that exceed their means. Income adjustment would return Medicare to a true insurance program. This means that the safety net will be strengthened and ensure that all Americans, of every generation and income level, will get the financial assistance to pay for retirement health care costs if and when they need it. To encourage Americans to prepare adequately for retirement, the Heritage premium support plan pairs Medicare and other entitlement reforms with comprehensive tax reform that makes it easier to save and invest for the future.[20]

Congress: Combine Income Adjustment with a Premium Support Model

Income adjustment as part of a premium support system offers significant improvements over the income adjustment used in the current Medicare program. It allows for a more transparent and intentional method of adjusting government-provided benefits to reflect income.

Less Risk of Falling Value. At the same time that expansion of income adjustment is an almost-assured deficit-reduction strategy for Medicare in the future, the Medicare bureaucracy’s expanded powers under Obamacare will allow it to control costs from the top down by paring down reimbursement for providers and treatments. Seniors can thus expect the quality of Medicare coverage to decline even as more Medicare beneficiaries pay higher premiums for dwindling access to the providers and services they need.

Conversely, in a premium support model, higher-earning seniors would receive a reduced contribution, but it would reflect the actual value of available plans. The wealthy would also benefit from access to a marketplace and improved value due to cost-containing pressure from engaged consumers.

Intentional Income Thresholds. Obamacare froze the income thresholds that determine whether seniors pay an income-related premium until 2019. This means that each year, more seniors will pay higher premiums, since increases in their income due to inflation may push them into a higher income bracket, which will not change to reflect inflation. While 3.5 percent of Part B enrollees paid higher, income-related premiums in 2011, about 10 percent of beneficiaries will do so by 2019. Eight percent of Part D enrollees will pay an income-related premium.[21] Proposals from both sides of the aisle further expand income-related premiums to 25 percent of Medicare recipients.

The Heritage model would reduce Medicare’s contribution to seniors with higher incomes at a lower income threshold, but the threshold would be indexed to inflation so that the proportion of seniors receiving less assistance would increase more slowly through the years. Less than 10 percent of seniors would initially receive a reduced contribution, and only the wealthiest 3.5 percent would no longer receive taxpayer-subsidized health coverage.

Unlike the status quo, the Heritage plan also balances the federal budget and makes Medicare permanently solvent, removing the need to further expand the definition of “wealthy” down the road as a way to reduce costs.

Predictable Premiums. Current income adjustment includes drastic changes in premiums from one income bracket to another. In 2012, individuals with an annual income of $85,000 or more pay 140 percent of the standard premium, which increases to 200 percent, 260 percent, and 320 percent for the top three income brackets.

These steep increases can be difficult to anticipate if they result from modest changes in income. The Heritage model instead reduces the Medicare contribution for high-earning seniors gradually, ensuring that if income changes slightly from one year to the next, it will not result in a major jump in costs. Phased-down contributions begin at $55,000 for individuals, after which the contribution decreases by 1.8 percent for every $1,000 in income above the threshold. It is phased out completely when an individual’s retirement income exceeds $110,000.

Another key difference between the Heritage plan and the current Medicare program is that under the Heritage plan, seniors would receive Medicare benefits by way of a contribution from the federal government, not as a defined benefit, so rather than requiring the wealthy to pay more, they would simply receive less. The current system does not allow seniors to pay less if they find a more affordable option, since it increases the mandatory, inflexible premiums that beneficiaries must pay to the government.

Change Course Now

Medicare currently represents a losing equation for young and old, seniors and taxpayers. Medicare is spending taxpayers’ money faster than any other government program. It is facing insolvency in its hospitalization program, and it is generating trillions of dollars of massive long-term debt.

Congress and the American people will have to make a choice. Medicare’s current course is disastrous, for seniors and taxpayers alike. There are finite resources available to reverse the current course, but the faster that policymakers act, the less difficult the task will be.

There is a better alternative. That alternative rests in harnessing the market forces of choice and competition, and making them the centerpiece of reform, while targeting aid to those who need it most.

—Kathryn Nix is a Policy Analyst in the Center for Health Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation.