In May 2015, the Illinois Supreme Court invalidated a 2013 state pension reform law as violating the Illinois constitution.[1] The law (hereinafter “Pension Reform Law”),[2] which adjusted benefit provisions and retirement ages, was held to conflict with the part of the state constitution that reads: “Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State…shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.”[3]

In terms of unfunded pension liabilities, Illinois ranks dead last in the nation.[4] But with 93 percent of state retirement systems underfunded, according to Wilshire Consulting’s 2015 report, the need for pension reform certainly extends beyond the Prairie State.[5] As such, how Illinois responds to the recent decision by the state Supreme Court will set an example—whether positive or negative—for other states attempting to resolve pension crises. Governor Bruce Rauner (R) and the state legislature should make clear that they intend to act with fiscal prudence.

The Extent of the Current Problem

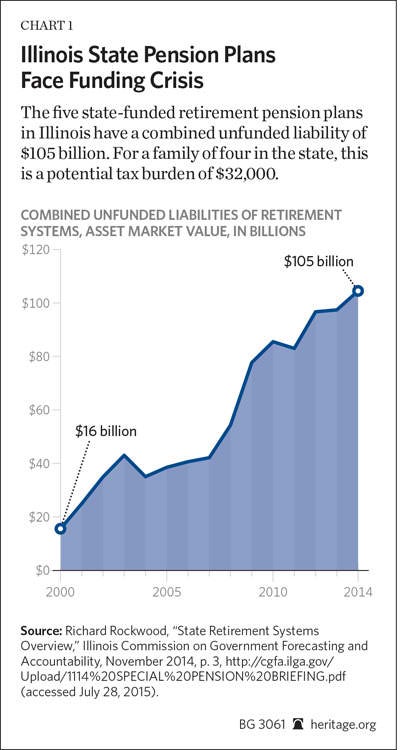

The five state-funded retirement pension plans in Illinois provide traditional defined-benefit schemes under which members earn specific benefits based on their years of service, income, and age. This pension system is woefully underfunded by nearly $105 billion based upon asset market value[6] ($111 billion using actuarial value)[7]—a potential tax burden of more than $32,000 for each family of four in the state. And it is getting worse. From 2000 through 2014, the unfunded liability (by asset market value) jumped 571 percent, including a 34 percent increase in the past five years.[8]

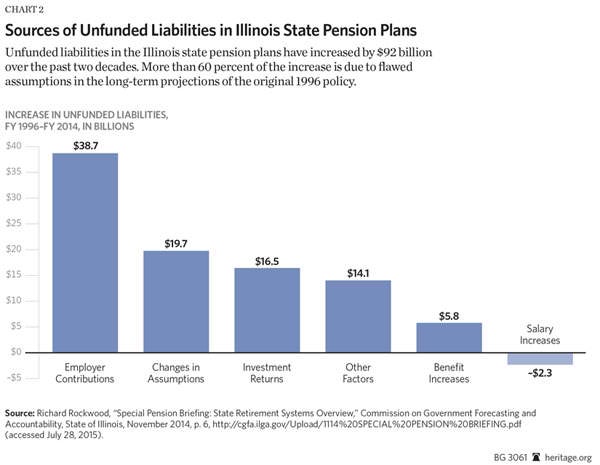

Since the enactment of the 50-year funding policy in 1996, the gap has widened by more than $92 billion. And it is a mistake to assume that this widening gap is driven solely by employer underfunding; since 1996, less than 42 percent (just $39 billion) of the $92 billion jump in unfunded liabilities is the product of actuarially insufficient employer contributions. Meanwhile, changes in investment return assumptions and lackluster investment returns through the period account for nearly the same portion of the increase—39 percent ($36 billion). Moreover, nearly 60 percent of the increase since the enactment of the 50-year funding policy in 1996 is due either to correcting the original, overly rosy actuarial assumptions, or to increasing promised benefits.[9]

Another sign of the growing crisis is the declining “funded ratio,” which plunged from an already dismal 60.3 percent in 2005 to just 42.9 percent in 2014. This decrease would be even worse had the state not resorted to selling $10 billion of pension obligation bonds.[10] This infusion of capital from the proceeds of this new long-term debt reduced unfunded liabilities by $7.3 billion in 2004. The reason that it did not reduce liabilities by $10 billion is that the state paid all of its 2004 pension contributions with this long-term debt, rather than other incoming revenues.[11] Issuing new debt to reduce unfunded pension liabilities is nothing more than rearranging deck chairs. Debt is debt.

In effect, failure to plug Illinois’ pension hole will likely result either in taxpayers facing egregious tax hikes in the future as current workers retire, or in future retirees facing significantly reduced benefits. Indeed, the liability could turn out even worse than projected. For instance, present assumptions include investment returns of 7 percent to 7.5 percent per year.[12] This projection is a very optimistic return on investment in today’s economy, and if returns lag behind the projections, the liability will grow even larger. Since 1996, the gap has widened by more than $16 billion—precisely because investment returns were less than estimated.[13]

Yet politicians are largely ignoring the problematic gaps, lest they antagonize either the general public by imposing tax hikes or the public-sector unions by cutting benefits adequately. Rather than reforming the system now with minimal discomfort, such delays threaten future taxpayers and pensioners with far more significant measures. The power of compounding interest might help savers, but it harms debtors like the State of Illinois.

Tepid Reforms Meet Strong Legal Opposition

In the face of a deepening pension crisis, the legislature passed reforms to partially resolve this problem. Despite various changes to future options in the pension program, the changes to existing plans were quite tepid. First, the reform act delayed the date of the start of benefits for those currently under the age of 46 by up to five years. Second, it based pensions off a maximum—but still generous—$109,971 salary in 2013. This cap, it should be noted, would have increased according to the inflation rate. Third, the 3 percent annual automatic cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) were adjusted to more closely track inflation, which is often less than 3 percent.[14] Fourth, the act eliminated at least one, and up to five, annual annuity increases from beneficiaries. Finally, it changed the benefit base calculation for annuity benefits. These adjustments in aggregate were minimal, eliminating just one-fifth of the total unfunded liabilities.

However mild the legislative solution, unions immediately challenged these reforms in Illinois state court.[15] Five separate lawsuits were filed, before being consolidated into one case before the state circuit court of Sangamon County. In brief, the unions argued that the state constitution prohibited these minor reforms through the “pension protection clause” in the Illinois constitution. This clause, added in 1970 as an amendment to the state constitution, reads:

Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.[16]

Relying upon this provision, the circuit court in In re Pension Reform Litigation struck down the law entirely. In affirming that judgment, the Illinois Supreme Court addressed three issues. First, the Court held that each of the five benefits calculation changes constituted a diminishment or impairment, and thus violated the Illinois constitution. Second, the Court held that the State’s argument that fiscal emergency overrode the Illinois constitution failed. Finally, while portions of the law (including prospective pension reform) were not implicated by the Supreme Court’s logic, the Court struck the law down in its entirety, noting that once it struck down the “inseverable” provisions of the pension reform, the rest of the law “all but evaporates.”

Since the opinion simply struck down a law amending pension obligations, the effect of the decision is unclear. Must the governor actually cut immediate checks to any beneficiaries? Is the State of Illinois legally obligated to immediately raise taxes or cut other services, even in the absence of a clear statutory authorization?

As it happens, one intermediate court in Illinois has opined on the matter. In American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31 v. State, on interlocutory appeal, an Illinois state court held that a trial court had jurisdiction to compel state officials to issue paychecks to state employees.[17] This case involved Chicago pension reform passed in 2014 that in many ways mirrored the statewide pension reform passed in 2013. The court cited In re Pension Reform Litigation, stating, amazingly, that “the prohibition against impairment of contract” must be applicable to a “governmental failure to act.” In addressing the separation of powers concerns, the court attempted to lay some limitations on its own power, noting that “in the event of a protracted budget standoff, courts may legitimately be called upon to intervene.” In essence, the court, acting as a Schmittian sovereign, has taken upon itself to define what constitutes an emergency, and has stepped in to resolve that emergency.[18] A constitutional crisis in Illinois has been teed up.

Moving Forward

The State Can Prioritize Cash Flow. While the Illinois Supreme Court in In re Pension Reform Litigation spilled much ink discussing a selective legislative history and conflating the accrual of a legal right to benefits with the obligation of the governor to actually cut a check, it did not order the governor to actually do anything. While it might be the case that absent a new constitutional amendment, the state legislature cannot “diminish or impair” benefits by changing how much is owed, the governor is certainly not obliged at any particular point in time to cut a check.[19] Commercial contracts, for example, and commercial law, in general, provide default terms in contracts that explain what happens when a debtor fails to meet an obligation—missing a loan payment, for example, will accrue fees and interest, and in no way discharges the original loan.

Governor Rauner should make clear that the state government has a plan for the day Illinois runs out of money. In January 2015, he issued a “spending freeze” executive order, 15-08, designed to limit future state obligations.[20] That was a responsible step. But the governor should also lay out a spending plan for the day when state coffers actually run dry, and make clear that on a day-to-day basis, the first debts that will get paid are emergency services—state troopers, for example, and followed by highway repair, state contractors, salaries of state employees, and so forth. What should be paid last are state pension obligations, and if there is no money left over, too bad. By making clear the order of creditors, the governor will be sending a strong message that unions should come back to the negotiating table. It is, after all, better to be reasonable and receive something than to be unreasonable and receive nothing.

There are downsides to such an approach, however. Certainly, if the governor reiterates a commitment to pay the pension obligations, but prioritizes other state payments, presumably statutory or contractual interest and penalties would accrue. Pensioners would have larger pensions on paper, and the state’s current and future creditors would have to assess whether Illinois is playing fiscal games or getting serious about its debts, but such a prioritization plan would help salve the fiscal pain. Given the terms of the recent Illinois Supreme Court ruling, as bad as it is, this prioritization option still appears a viable route.

Repeal the Constitutional Amendment. The Illinois Supreme Court is obliged to follow the Constitution of the State of Illinois. What if the state repealed the Pension Protection Clause through the Article 14 convention amendment process? With the approval of 60 percent of both legislative houses, a referendum to amend the Illinois constitution could be placed on a statewide ballot. A simple majority of the electorate could then choose to start down the road to fiscal sanity, and make it far less likely that a lawsuit challenging such an action would prevail in state court. By repealing the Pension Protection Clause, the State of Illinois would be explicitly changing the state law status of pension obligations from vested entitlements to ordinary legislative largesse on which no one can fairly rely. In Illinois, this means a far more extensive pension reform than that approved by the legislature in 2013. At the very least, such a constitutional amendment in the state of Illinois would prevent future benefits from being written in stone.

Would such a constitutional amendment preclude a federal lawsuit? At first glance, one might presume that an intended pension beneficiary could sue Illinois in federal court. The U.S. constitutional system, however, envisions states as sovereign entities that cannot be sued unless they consent to be sued, which means they must waive their sovereign immunity.

Even if a state has waived its sovereign immunity, federal courts have often held that expectations of public pension benefits are not “property,” and when a state government pays out such benefits, it is usually just making good on legislative generosity, not paying out due to any legal obligation. In 1999, for example, the National Education Association (NEA) sued Rhode Island for amending its teachers’ pensions, and the NEA lost.[21] The federal appeals court in that case held that amending the pension benefits did not violate the Obligation of Contracts Clause, the Takings Clause, or the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution. (The NEA tried just about every legal argument in the book.) Even if a federal court were to hold that certain vested benefits were unamendable, others (such as the inflation-adjustment provision) might be deemed permissible.

Re-pass Pension Reform, and Make it Forward-Looking. At a minimum, the legislature should re-pass pension reform, and make it entirely forward-looking. The Illinois Supreme Court struck down the reform in toto but acknowledged that prospective pension reform would not be unconstitutional. At a minimum, such reform would decrease the rate at which the pension crisis is growing, although obviously at even less than the one-fifth of total unfunded liabilities that the previous reform represented. To give one creative solution, John Tillman, CEO of the Illinois Policy Institute, explains:

Ultimately, the only way Illinois can break the cycle of siphoning more and more tax dollars and sacrificing more and more state programs to pay for pensions is to follow the lead of the private sector and move new employees to a 401(k)-style system.[22]

And Illinois Policy Institute has articulated its own pension reform plan which could end the crisis.[23] Rather than guarantee lavish retirement packages through a “defined” benefit system, the state would shift to “defined contributions” to employees’ retirement accounts. In this way, employees would gain increased responsibility for and control over their own future—while reducing the propensity of the legislature to dole out special favors to public-sector unions (in the form of future benefits) at the expense of future generations of Illinois taxpayers.

The Pension Protection Clause Harms Taxpayers and Union Members

It is clear that union bosses influenced the Illinois delegates gathered in 1970 to pad the constitutional amendment with what they considered extra union protections. As delegate Helen Kinney (R–Hinsdale) stated during the lead-up to approval of the pension clause: “If a police officer accepted employment under a provision where he was entitled to retire at two-thirds of his salary after 20 years of service, that could not subsequently be changed to say he was entitled to only one-third of his salary after 30 years of service, or perhaps entitled to nothing.”[24] In the end, delegates at the 1970 Illinois constitutional convention passed the pension protection clause by a lopsided 57–36 bipartisan vote.[25] While the statement of a few legislators does not settle the issue of whether Illinois pension benefits are tantamount to a legal right of future beneficiaries, it seems evident that the state constitutional amendment was designed to at least make amending pension benefits more politically difficult.

Although throughout the convention actuaries continually broadcast warnings about the growing unfunded liabilities, unions pressed for more and more concessions. As John Tillman puts it: “Illinois’ political elite have devised a pension scheme that is excessive, bloated, corrupted and was never affordable for Illinois taxpayers.”[26]

It is obvious how such a scheme harms taxpayers—forcing other social services cuts and tax hikes is easier than renegotiating union benefits. However, the Pension Protection Clause also usurps the executive authority of the governor of Illinois and the legislative authority of the Illinois House and Senate by allowing the Illinois Supreme Court to determine permissible fiscal decisions.[27] Certainly, the people of Illinois were within their rights to set up such a system through constitutional amendment, but it is unlikely this is what they thought they were doing in 1970—major amendments to state separation of powers probably would not be effectuated so obliquely. As a general rule, important matters of legislation and execution of the laws should be left to the political branches best equipped to handle those issues. This is important as a matter of administration but also of democratic legitimacy.

Further, this scheme, as interpreted by the Illinois Supreme Court, now radically changes the bargaining landscape regarding pensions, something that will have some negative consequences for union members. Absent the constitutional amendment, a somewhat vague pension benefit increase could be passed by the legislature quite easily, in part because it could be repealed or amended easily. Now, however, the legislature will have an incentive to be extremely careful in drafting future benefits. Indeed, because any new benefits will be written in stone, cost-benefit analysis would likely err on the side of overestimating future costs to ensure that the legislature would be able to appropriate enough money to pay its bills. Because laws passed based upon mistaken estimates cannot be subsequently amended through the ordinary legislative processes, some lawmakers might be discouraged from voting for benefit increases that they otherwise might support. Further, taking any benefit change off the negotiating table actually removes bargaining chips from unions, and prevents reasonable compromises from being made. These are real harms to unions and union members that should be considered.

Conclusion

Absent fiscal reform, taxpayers and beneficiaries in Illinois will needlessly suffer. Look no further than bankrupt Detroit and nearly bankrupt Puerto Rico for a glimpse at how Illinois-style cronyism stunts growth. And, because states such as Illinois likely will be clamoring for a federal bailout in the absence of reform, the entire country has an interest in such a crisis being averted.

It was wrong for the unions to seek to write pension benefits in stone by making them a part of the Illinois constitution. Not only did this constitutional amendment contribute to Illinois’s current fiscal mess, but it also makes it more difficult to negotiate and secure future pension benefits. It was wrong for the convention delegates to enshrine these protections in the Illinois constitution. And it certainly was wrong to shackle future taxpayers with the burden of meeting these enormous obligations over the next 40 years. In effect, Illinois legislators purchased power by doling out cushy pensions. Bankrupting the next generation of Illinoisans, however, simply because the Supreme Court of Illinois has deemed legislators’ hands tied due to a mistake that was made in 1970 is not a viable or sustainable option. Three wrongs do not make a right.

—Andrew Kloster is a Legal Fellow in the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at The Heritage Foundation. Joel Griffith is a former Research Associate in the Project for Economic Growth, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.