Understanding the Defense Budget

Frederico Bartels

Like the familiar drawings that appear to be a duck or a rabbit to different people, when people talk about the defense budget, it often seems they might be talking about completely different things. There are many different accounts and permutations of what could properly be considered the U.S. “defense budget.” From a narrow view of the direct resources under the control of the Department of Defense (DOD) to a much broader view of discretionary versus mandatory spending, many nuances need to be considered if one is to have an informed discussion or understanding of the U.S. defense budget.

This essay is meant to provide a better understanding of the resources that are dedicated to our national defense. The goal is not to give a definitive answer, but rather to give people the information they need to arrive at conclusions that are as well-informed as possible. In addition to definitional elements, where individuals are located within the U.S. national security apparatus plays a key role in how they define the defense budget.

All of these perspectives, however, should use the Constitution of the United States as their starting point.

The Constitutional Foundation

In the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, the Founders state that the government has the responsibility to “provide for the common defence.”1 This is restated in Article 1, Section 8, as one of Congress’s enumerated powers.2 The Heritage Foundation’s Guide to the Constitution calls this purpose “obvious—after all, it was by this means the United States came into being.”3

The crucial political question is: How we are to define what it means to provide for the common defense, how much “defense is enough,” and how much we as a nation are willing to pay for that defense? The constitutional need to provide for the common defense is the starting point for understanding the role of the armed forces within the American political context, but it is not the final word by any means. What is clear is that defense—unlike many of the other activities that are currently undertaken by the federal government—is a fundamental constitutional responsibility.

Providing a common defense is understood in the Constitution as a function that can be performed only by the Union and thus resides unambiguously at the federal level. Many governmental functions, such as the provision of public security by localities or the state-level provision of identity cards, can and should be conducted and administered at lower levels of government. Common defense is not such a function.

Many organizations at the federal level have a role in our national defense, and there are substantial differences in what could be considered the defense budget that reflect the perspective of the organization or person talking about the defense budget. Many countries, for example, consider expenditures associated with support to veterans as part of their defense budget, while the United States has a separate Department of Veterans Affairs that is not usually considered part of the defense budget.

What Is the Defense Budget?

When discussing the defense budget, one should always begin by defining the terms being used. Depending on who is talking about the defense budget and the message being highlighted, different numbers can be used. In many cases, the choices being offered depend on how the specific institutions define the terms, and the implications are not immediately obvious.

Even within the executive branch, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Department of Defense have different concepts of the “defense budget.” Congress has still another definition because it is organized by committees and focuses its attention on the different appropriations and authorization bills.

There is an initial division between discretionary and mandatory spending in the defense budget just as there is in the overall federal budget. Discretionary spending is the element of the budget that is annually debated and appropriated by Congress. Mandatory spending, on the other hand, is not debated annually and is defined largely by formulas that govern the various benefit programs operated by the federal government such as Social Security and Medicare.4 The defense budget includes both mandatory and discretionary funding, but most defense dollars are classified as discretionary.

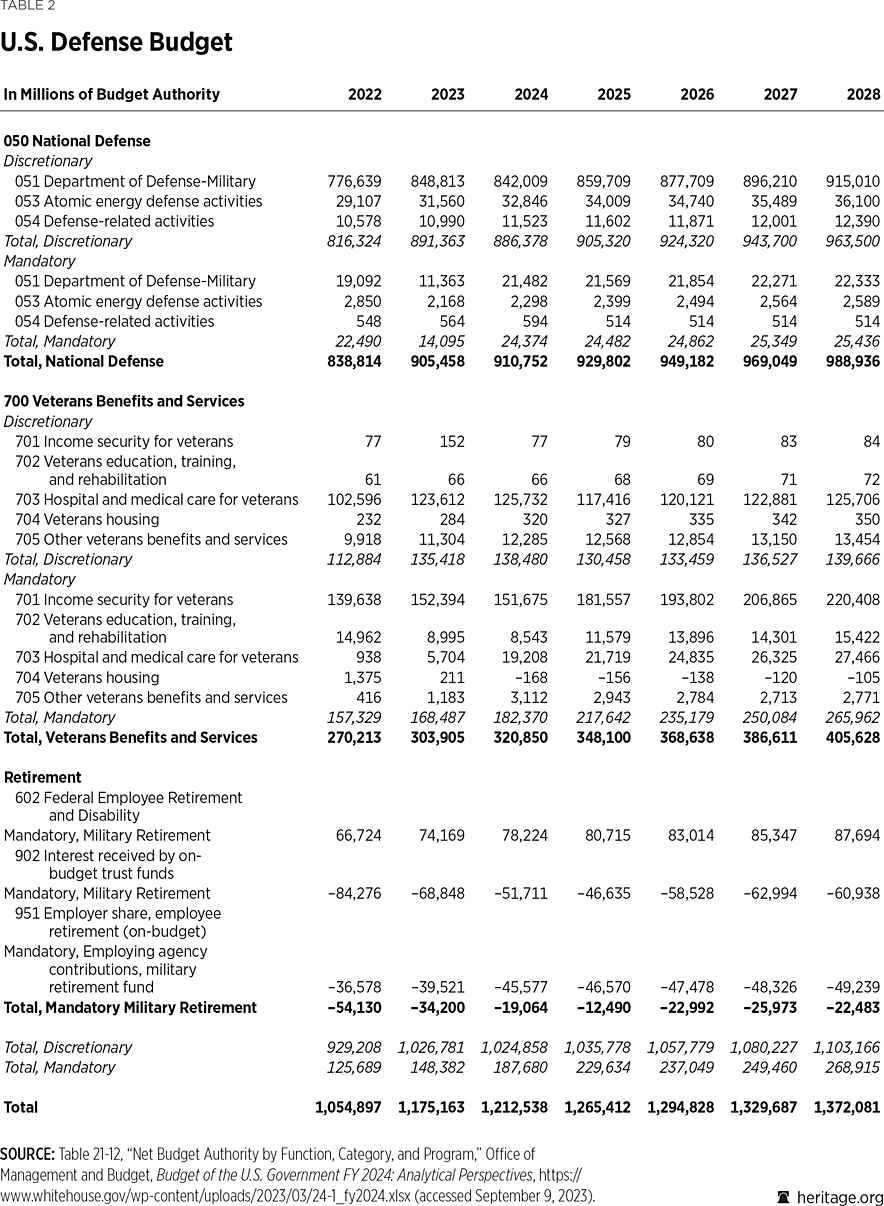

Table 2 contains different possible combinations of what could be considered colloquially as the “defense budget.” This table is based on OMB’s projections and categories, which can provide a fuller picture because it incorporates both mandatory and discretionary spending and contains data on every government agency. Realistically, the defense budget for fiscal year (FY) 2024, for instance, could be said to be as low as $842 billion if you focus just on discretionary spending controlled by the Department of Defense or as high as $1.2 trillion if you include Veterans Affairs and other possible mandatory spending.

Of the many possible ways to consider the defense budget, it is important to highlight a few of the ones that are most commonly used in the executive branch. The first one, known as 050, encompasses the DOD, Atomic Energy Defense Activities within the Department of Energy,5 and other defense-related activities. This category was utilized in the Budget Control Act of 2011 to cap discretionary spending. It was also used in the legislation that raised the debt ceiling in 2024. Another important category, known as 051, is the DOD’s portion of the national defense budget within OMB tables. It constitutes the major portion of 050 but is usually discussed and debated separately from the other functions within the category and is often referenced as the “defense budget.”

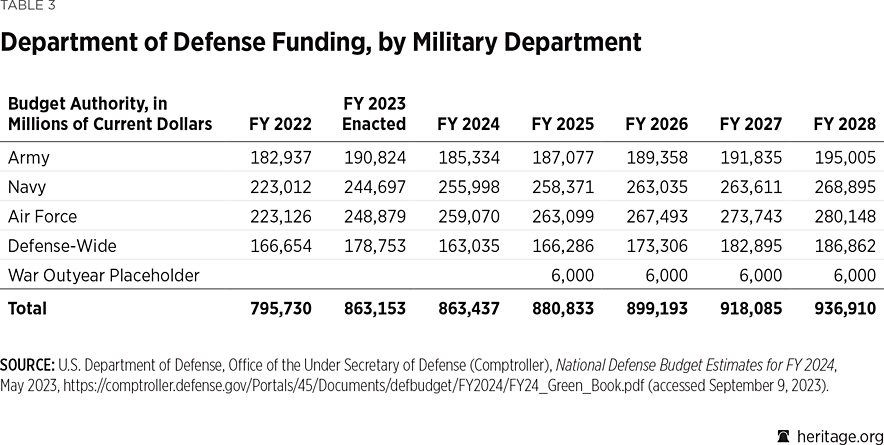

Within the DOD itself, different sets of numbers are used to define the defense budget. As one would expect, the first is the 051 category because these are the funds under the DOD’s control and include both mandatory and discretionary spending. Category 051 numbers can be described as the defense budget, and in many reports and news stories, these are the numbers that are most often used. Table 3 shows the budget for the Department of Defense broken down by military department, which is different from the OMB data in Table 2.

One additional set of numbers that is commonly discussed and characterized as the defense budget is the funding appropriated by Congress. Because the Constitution specifies that Congress must appropriate every dollar that is withdrawn from the Treasury, appropriations bills are among the most crucial pieces of legislation that are passed in any fiscal year.

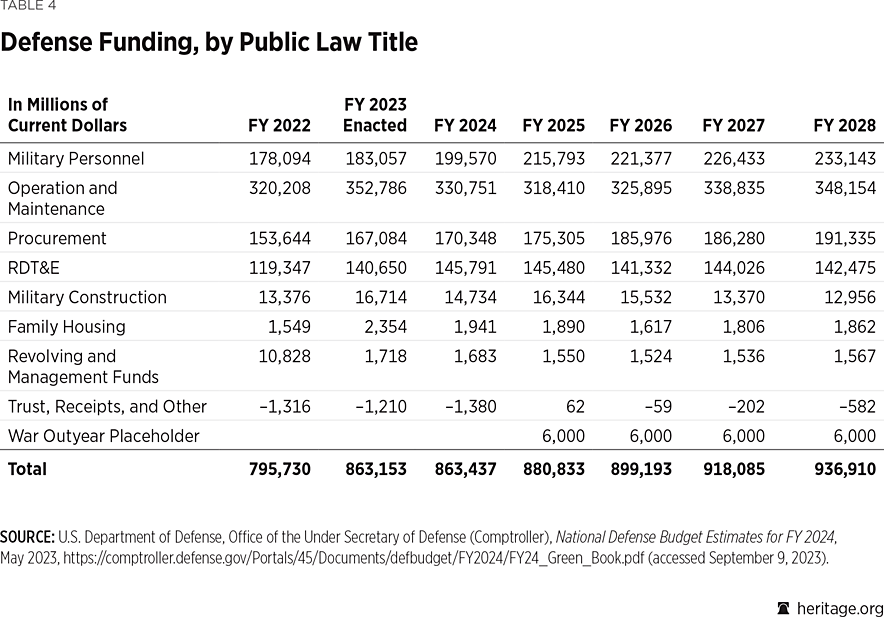

The Department of Defense receives resources mainly through two distinct appropriations bills: Defense Appropriations and Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations. This division reflects the different public law titles and the characteristics of appropriated dollars that compose the defense budget.

The defense appropriations bill includes military personnel; operations and maintenance, procurement; research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E); and revolving funds as shown in Table 4. Military construction appropriations include mainly military construction funds and family housing. Table 4 depicts funding (both appropriated and projected) for various fiscal years broken down by public law title.

Beyond the appropriations bill, the same resources that the Department of Defense receives are also authorized by the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), a bill that has been passed and has grown in length for more than 60 consecutive years. The DOD is one of the very few federal departments that reliably has its funding both authorized and appropriated.6 The NDAA is sometimes referred to as a defense policy bill because it does not actually appropriate dollars to the DOD; it sets policy and establishes limitations on how the appropriated dollars will be used through the fiscal year. The NDAA includes important measures that have both financial and practical implications for how the nation provides for the common defense.

Altogether, there are several ways to talk about and represent the defense budget. The first thing that an informed reader should do is understand who is communicating so he or she can understand what that person means by the defense budget.

It is also important to know that defense is not the biggest item in the federal budget; entitlements have that distinction.7 Nor is defense spending the primary factor driving the nation’s financial problems, especially the explosive growth in public debt and the annual federal budget deficit. In addition, current plans have the relative burden of defense decreasing over time as the economy grows. Understanding the broader context of the federal budget is therefore very important when considering the defense budget.

The Burden of Defense on the Federal Budget

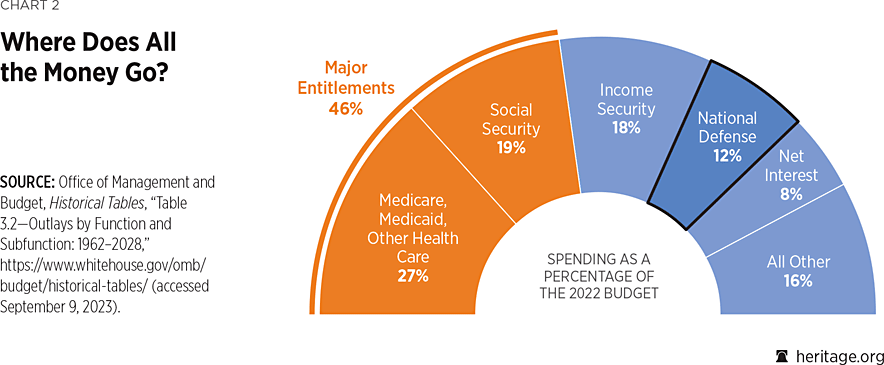

As in all things related to the budget, it is important to understand the burden of any financial expense relative to the available resources and the importance associated with the tasks that are being resourced. When commentators focus narrowly on discretionary spending, defense is usually noted as commanding a huge share of the budget. However, when one looks at the whole of the federal budget, the picture is quite different. This difference is portrayed in Chart 2.

In the context of the whole federal budget, in FY 2022, national defense as defined by the OMB consumed 12 percent of the federal budget. This is by no means an insignificant amount, but it is dwarfed by other federal expenditures, including health care insurance and provision, income security, and many other governmental functions for which Washington is currently responsible.

Medicare, Medicaid, and other health care spending accounts together comprise the biggest portion of the budget: 27 percent. Social Security constitutes the second biggest element at 19 percent. Income Security—a collection of programs such as Civil Service Retirement and Disability, Earned Income and Child Tax Credits, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Housing Assistance—follows closely at 18 percent. The 12 percent representing the broader national defense enterprise is followed closely by net interest on our debt, which currently stands at 8 percent, although the burden of servicing our national debt through interest payments is likely to increase as interest rates in the United States rise.8 Every other function of the federal government, from the administration of justice to the collection of taxes, accounts for the remaining 16 percent. It is important to keep in mind how the government truly allocates taxpayers’ dollars when considering the defense budget.

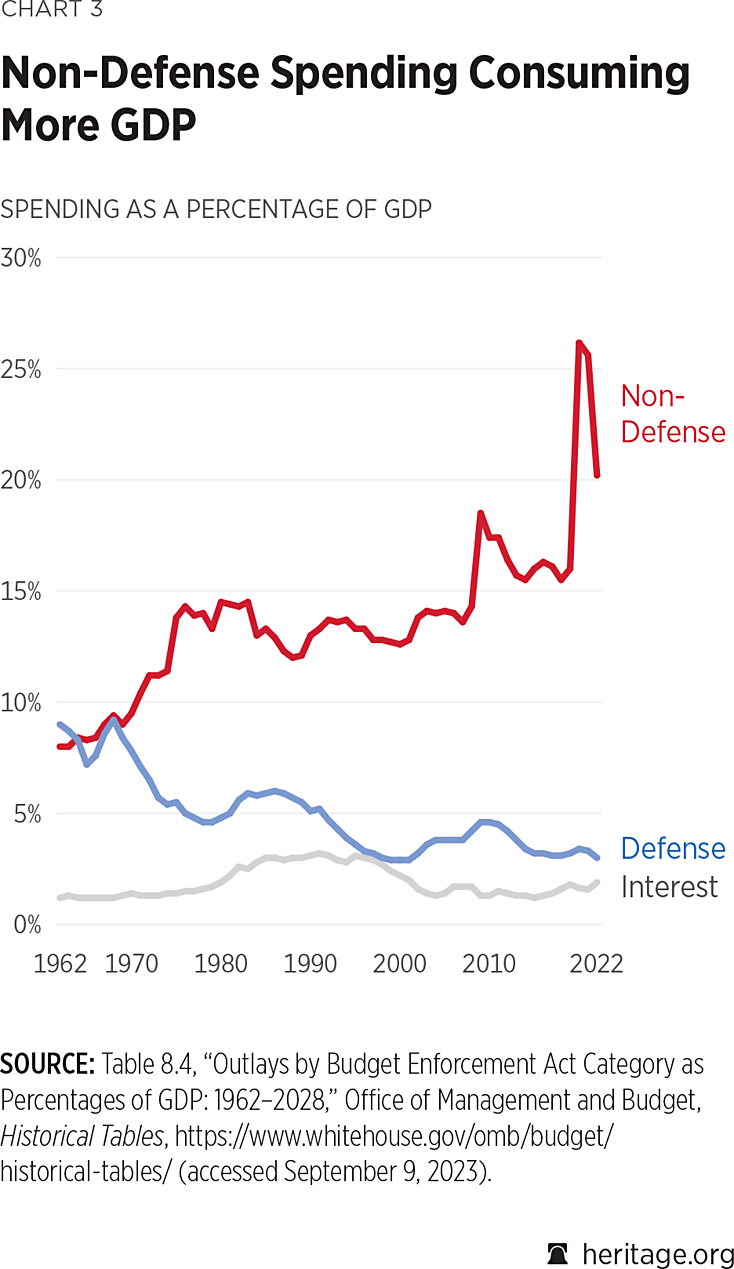

It is also important to understand the size of the federal government’s obligation when compared to the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). Chart 3 portrays how much of the nation’s GDP is consumed by three different categories of federal spending that include both mandatory and discretionary spending: defense, non-defense, and interest on our national debt. This picture conveys two important messages:

- The relative burden of our national defense has declined steadily over the past 60 years and

- The portion of government resources allocated to the provision of non-defense services and goods has increased substantially over time.

Chart 3 also provides a valuable baseline for the cost of interest on our national debt over the past 60 years—a consideration that has become increasingly relevant as interest rates have risen in the past few years.9

All in all, the relative burden of defense has gone down over the past 60 years. Put another way, defense has become more affordable for the country.

Trajectory of the Defense Budget

The Department of Defense organizes and reports on its budget in multiple categories and with multiple ways of displaying the information in a yearly document, the National Defense Budget Estimates, commonly known as the “Green Book” because of its seafoam green cover pages.10 Many of its tables contain data back to FY 1948. Many also contain estimates for the coming four fiscal years.

The Green Book also provides three different categories of resources: budget authority (BA); total obligational authority (TOA); and outlays. The simplest differentiation of these is that budget authority includes the new yearly resources that the department can obligate; total obligational authority counts resources appropriated in previous years that can be obligated in a different fiscal year; and outlays are actual disbursements made by the Treasury on behalf of the DOD. Of these, budget authority is the term used most frequently in public debate because it reflects the resources appropriated in the current fiscal year.

There is another differentiator that is relevant to understanding the data provided by the DOD: current versus constant dollars. Current dollars represent the face value of an item in the present, as if you are spending money today to buy that item. When people reminisce about a bottle of Coke in the 1950s costing less than a dollar, they are talking about current dollars. Constant dollars, on the other hand, represent a price relative to a past price in a given base year, usually the current year—for example, how much a bullet cost in 1978 adjusted to be in 2024 dollars—thus accounting for the effect of inflation over time. Currently, there is a broader appreciation of this difference because of the recent spikes in the inflation experienced by the public.

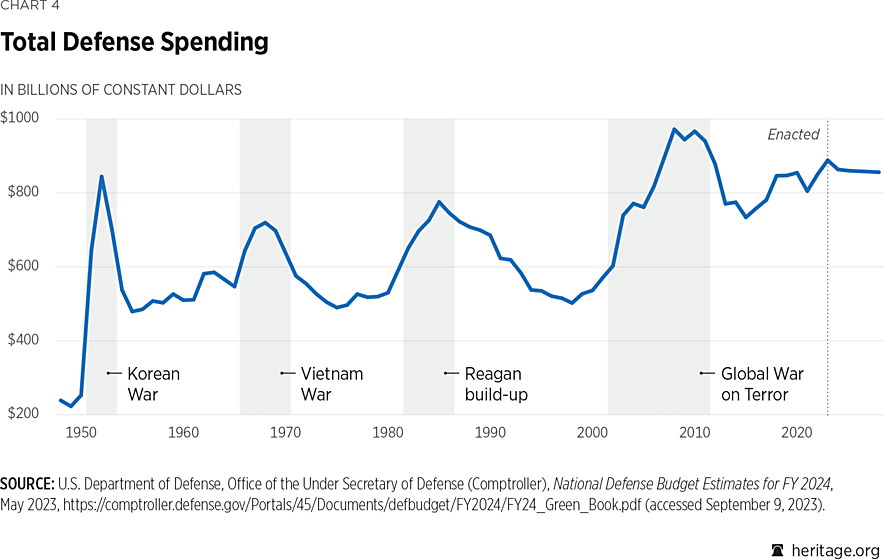

The Department of Defense was created in 1947, and Chart 4 contains both mandatory and discretionary budget authority in FY 2024 constant dollars for the DOD since FY 1948. Because of its normalization with constant dollars, the chart provides a more informative picture of the resources that have been allocated to the DOD and, more important, of the relative resources that it had available over time to purchase goods and services. The constant dollar number is an approximation that is derived from an economic understanding of rising costs and inflation. It is not a perfect representation of the historical value of the dollar, but it provides a useful perspective.

Chart 4 reveals four distinct peaks and troughs in the defense budget during the past 70 years: the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Reagan military buildup, and the global war on terrorism. These increases reflect different periods in our recent history when there was a renewed attention and commitment to the military driven by both internal and external events. In these periods, the nation allocated more resources to its military. All are followed by reductions in defense spending, reflecting the nation’s sense that a danger had passed and it could invest less in its military.

Each of these waves reflects a combination of geopolitical pressures and internal politics. It is worth noting that the Korean War generates a more abrupt peak and trough, while the other peaks are smoother and take longer both to materialize and to dissipate. In the end, the defense budget is the product of political debate and considerations and thus reflects the political environment and how the leadership interprets and reacts to it.

During the Korean War, there was a quick spike that peaked in FY 1952 with $844 billion allocated to the Department of Defense. It is followed by the end of the war and a sharp drop in FY 1955 to $479 billion. It is worth noting that the data start in FY 1948 during the post–World War II era when military expenditures were severely reduced. Between FY 1948 and FY 1950, the DOD’s budget fluctuated at around $238 billion a year—a low point even when compared to the aftermath of the Korean War.

The next peak comes in FY 1968 during the Vietnam War when the Department of Defense had a $719 billion budget. After that peak, there was a slow and consistent decline until FY 1975 when the department’s budget reached a trough of $489 billion. This decline lasted for about five fiscal years. Then, in FY 1980, the department’s budget began an upswing that peaked in FY 1985 at $775 billion, largely under the Reagan Administration’s military buildup. Between FY 1986 and FY 1998, the defense budget once again consistently declined, reaching a low of $502 billion in FY 1998.

After FY 1998, the defense budget started to climb again, a climb that was accelerated by the September 11, 2001, attacks and the nation’s subsequent response to them with wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It peaked in FY 2008 with $971 billion allocated to the DOD. Interestingly, there was a quick drop in FY 2009 to $944 billion, then an increase in FY 2010 to $966 billion before another sustained decline that lasted until FY 2015 when the defense budget reached $733 billion.

Since FY 2016, there has been some increase in the defense budget, but it is still far from either a peak or a trough. In the past eight years, there have been slight increases and slight decreases with an annual average of $828 billion. There is not enough direction or time to serve as the basis for a concrete determination about the trend of the defense budget in recent years.

Fundamentally, the defense budget’s increase in constant dollars reflects our nation’s changed expectations of what the Department of Defense should do, how it should do it, and the availability of technology. The DOD’s mission has expanded significantly in the decades since the department was created. Today, the department not only prepares and fight wars, but also runs recruiting stations spread out across the country, runs schools and supermarket chains and medical facilities, and purchases billions of dollars of services and goods every year. Even small military bases provide multiple services from small sandwich shops to facilities that maintain extra-large airplanes.

Today’s DOD is expected to be able to mobilize within a moment’s notice and deploy almost anywhere in the world. Maintaining this level of preparedness and planning takes a substantial number of resources, both in manpower and in material. The United States’ armed forces have prepositioned stocks in strategic locations around the world, which is what allowed American forces in Korea to transfer equipment to Ukraine.11

The DOD also has unique requirements both in terms of security and in terms of material conditions that are fundamentally different from those of the commercial sector. Any DOD information technology system will have to handle access by at least three different types of users—military, civilian, and contractors—with different levels of access to information, even if they are only accessing unclassified information. The infrastructure required by our armed forces is incredibly detailed and prescriptive because they deal with matters of life or death. It goes hand in hand with our society’s expectation that our armed forces will value the lives of our servicemembers and the individuals who interact with them.

This is what Americans have come to expect from their armed forces, and it does carry a price tag.

The Defense Budget and the Military Departments

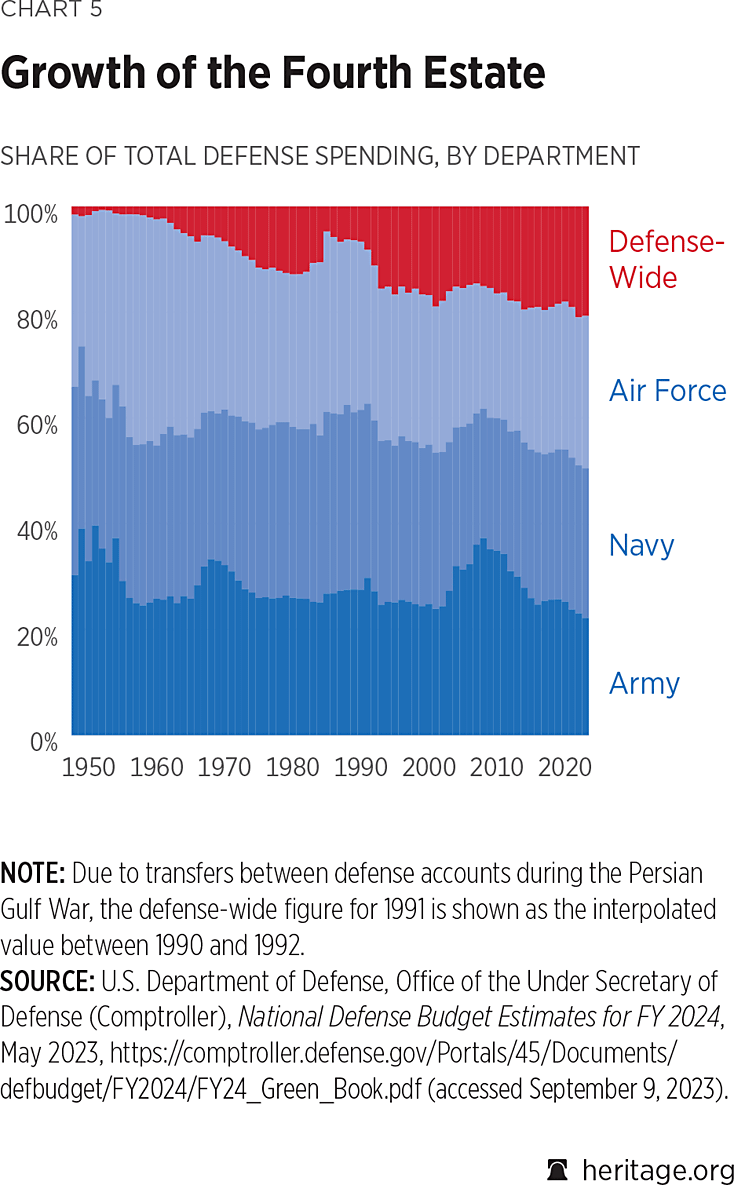

The Department of Defense is composed of three military departments—Army, Navy, and Air Force—and multiple agencies and field activities that are grouped under a budgetary category called defense-wide. Each of the five military services resides within one specific military department: The Department of the Army oversees the U.S. Army; the Department of the Navy, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps; and the Department of the Air Force, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force. The agencies and activities provide support functions to all of the military departments and services. Examples include the Defense Logistics Agency, the Defense Financial and Accounting Service, and a majority of the medical care expenses and many of the intelligence functions within DOD.12

These organizations collectively are known as the “fourth estate,” and most of their efforts represent efforts to consolidate and standardize some support activities that are common to all military departments. Each of these organizations within the DOD receives a portion of the defense budget.

There are many public discussions about the share of the budget that each of the military departments receives and whether such distribution should be equitable. However, the portion of the budget that each receives is not equal to the shares that others receive and has fluctuated greatly over time.13 Depending on the technological developments of the time and the external threats to which the armed forces were responding, the share received by each of the services has ebbed and flowed to account for the different challenges. The Army, for example, received a higher proportion of defense dollars in the years following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks because of the land wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, while the Air Force received a substantially larger share when it was establishing itself and there was an emphasis on air power and nuclear weapons under President Dwight Eisenhower.

Another aspect of the budget that deserves attention is the growth of defense-wide accounts that are associated with defense agencies outside of the military departments. They started as a few individual programs that were later centralized and as specific business functions that were made uniform and have since then expanded, progressively consuming a larger portion of the budget. The growth of these accounts since FY 1948 is depicted in Chart 5. These accounts have grown from a low of 0.7 percent of the defense budget in FY 1952 to a peak of close to 21 percent in FY 2022.

This is not to say that resources should not be allocated outside of the military services. The point is that there is a large portion of the defense budget, which has been consistently rising in recent years, that is controlled by different agencies and activities rather than by any of the military departments. During his tenure as Secretary of Defense, Dr. Mark Esper tried to consolidate the budget, shifting budget authorities and oversight over the defense agencies and field activities to the Chief Management Officer,14 but the office was not given enough time to mature and properly control the resources of the fourth estate.15

The common argument that each of the military departments receives a third of the defense budget and that it is a zero-sum game among the services is inaccurate. It does not consider the changes that take place over time and the significant role of defense agencies and field activities within the budget.

Changing Nature of the Defense Budget

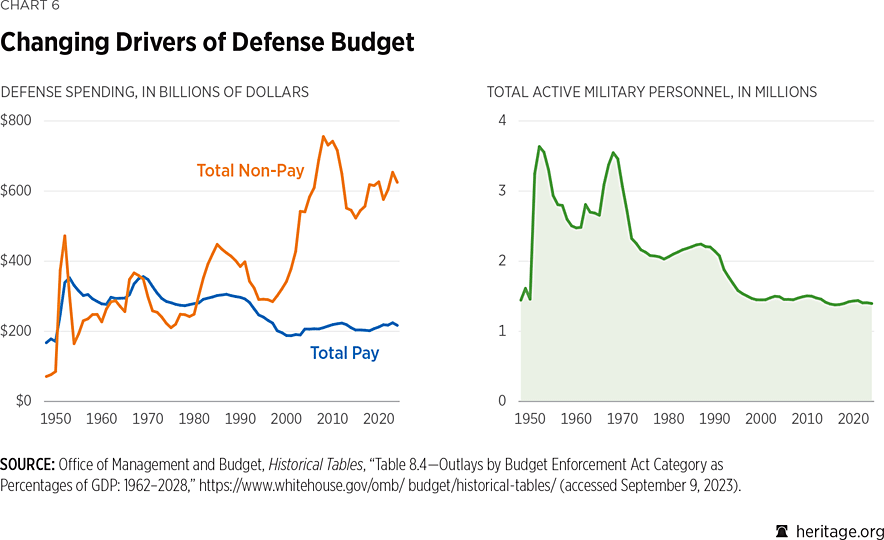

Since the end of World War II, the decrease in the number of members of the Armed Forces and the increased presence and complexity of technology have forced a substantial change in how the DOD allocates its resources. Chart 6 shows how the number of total active military personnel has decreased substantially from a peak of 3.6 million in FY 1952 to a low of 1.37 million in FY 2015. The last time the United States had 2 million individuals in its armed forces was in FY 1991. The U.S. has been reducing the active members of its armed forces since FY 1987.

The data also reveal how the DOD has invested a higher proportion of its resources in the category of non-pay items, which in this instance amounts to operations and investment—in other words, what it costs to equip and operate the force. In hypersimplified terms, pay is the cost of establishing the force and non-pay is the cost of using that force.

This is consistent with the technological evolution that the United States has experienced as a society over the past 70 years as the tools of war have become increasingly capable, complex, and costly. Every tool and machine that we have at our disposal today is undoubtedly more capable than those that our parents and grandparents had at their disposal. That is also true in the military where the information technology revolution has influenced everything from how people communicate to how weapon systems operate. These systems and support services are more complex, more capable, and more expensive to maintain and operate. Additionally, servicemembers have higher expectations with respect to what their organization provides them: An officer in 1970, for example, would have no expectation of having an individualized computer issued by the Army.

It should also be noted, however, that the peak level of resources available for operations and investments was between FY 2007 and FY 2011 when the country was heavily engaged both in two wars in the Middle East and in developing the new technology that was necessary to prosecute those conflicts.

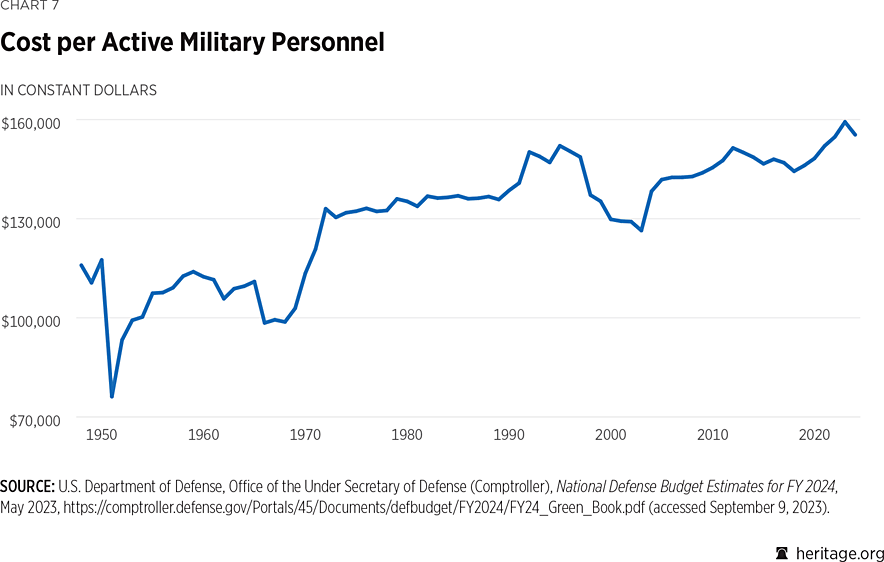

When it comes to pay, the decrease in the size of the force has not been matched by a proportional decrease in the amount dedicated to pay. In other words, as a practical matter, the level of resources allocated per servicemember has increased over time. This reflects the amount that is spent on salaries and benefits as well as other services provided to servicemembers that are not funded with resources labeled as pay.

Chart 7 reflects the increased compensation that has been required to account for the compensation the military must offer to remain competitive with the private sector. As Americans generally and servicemembers in particular have become more educated and productive, especially with the consistent introduction of new technologies, they have commanded higher wages in the market, and this is reflected in the relative increase of pay within the DOD.

The Defense Budget as Lagging Indicator

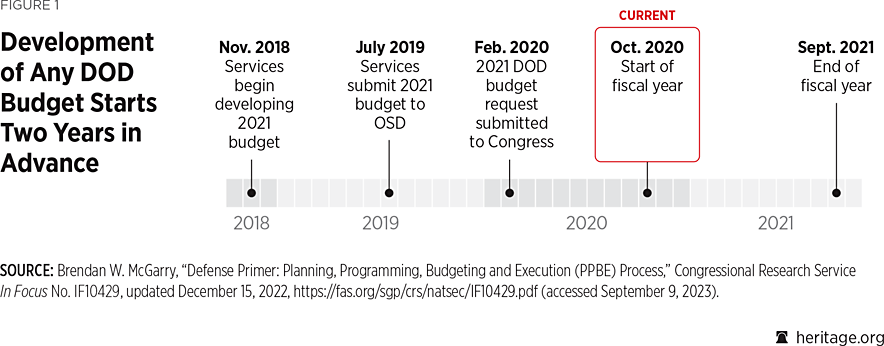

The defense budget is built through a unique process. The Department of Defense utilizes a system called Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution (PPBE) to build and execute its budget. This system was developed in the 1960s and is showing some cracks.16 The PPBE process defines how the DOD builds its budget and dictates the timelines for resourcing decisions. As illustrated by Figure 1, development of the services’ budgets starts at least two years before the fiscal year that they are intended to fund. This guarantees that the budget will present a projection of the future that is tied to past projections and assumptions. Thus, incorporation of a relevant innovation that was developed during the period between composition of the budget and the start of the fiscal year would be a notably challenging exercise.

Modifying resources that were programmed years in advance would be equally challenging because they represent real costs that would be incurred by a program or organization. Whether for good or ill, this makes the defense budget quite inflexible, and large movements of funds and changes in programming take several fiscal years to become fully apparent. It is common for new Administrations to say that it will take a few budget cycles to implement the changes desired at the Pentagon.17 Thus, the defense budget will always be a lagging indicator of the ongoing challenges being faced by our military. The PPBE system makes budgetary decisions very “sticky” and is inherently biased toward maintaining the status quo.

Further, because the budget is about allocating taxpayers’ dollars, the decisions that are made both inside and outside the department are ultimately political in nature. The final resolution of the defense budget rests with Congress, an inherently political body. However, politics also permeates the other levels of decisions involved in making the defense budget. The leaders who manage internal DOD programs will often base their actions on their expectation of what the services will do with their budget submissions, and the services will often base their actions on what they think the Office of the Secretary of Defense will do. In turn, the Secretary of Defense will anticipate and respond to the actions of the Office of Management and Budget, the President, and Congress. These interactions occur several times a day during all phases of the budget process.

There should always be continuous process improvement in the allocation of precious defense dollars. One such effort currently underway is the congressionally established Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Reform (PPBE Commission). Established by the FY 2022 NDAA and composed of 14 commissioners appointed by congressional leaders and the Secretary of Defense,18 it has conducted a variety of sessions to engage with the different individuals and organizations that participate in the PPBE process.19 The commission is scheduled to submit its final report in March 2024.

Conclusion

Regardless of the details and the process, determining the defense budget will necessarily be a political exercise that will have to take account of multiple divergent priorities and preferences. The political nature of such a determination makes it even more important that everyone involved has a clear understanding of the terms being discussed. After all, a 1.2 percent increase in the 050 line is very different from a 1.2 percent increase in the discretionary dollars controlled by the Department of Defense.

Endnotes

[1] Constitution of the United States, Preamble, https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

[2] “Congress shall have Power to…provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.” Constitution of the United States, Article 1, Section 8.

[3] Forrest McDonald, “Preamble,” in The Heritage Guide to the Constitution, https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/articles/0/essays/1/preamble.

[4] For a useful discussion of this question, see Brian Riedl, “What’s Wrong with the Federal Budget Process?” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1816, January 25, 2005, https://www.heritage.org/budget-and-spending/report/whats-wrong-the-federal-budget-process.

[5] The department lists seven categories of such activity: “(1) Naval reactors development; (2) Weapons activities, including defense inertial confinement fusion; (3) Verification and control technology; (4) Defense nuclear materials production; (5) Defense nuclear waste and materials by-products management; (6) Defense nuclear materials security and safeguards and security investigations; and (7) Defense research and development.” See U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Management, Directives Program, “Atomic Energy Defense Activity,” https://www.directives.doe.gov/terms_definitions/atomic-energy-defense-activity#:~:text=Any%20activity%20of%20the%20Secretary%20performed%20in%20whole,%283%29%C2%A0Verification%20and%20control%20technology%3B%20%284%29%C2%A0Defense%20nuclear%20materials%20production%3B (accessed August 11, 2023).

[6] Once dollars are appropriated, federal agencies can start to spend them. Authorizations are not legally necessary, but they play an important role in budgeting because they authorize the existence of programs and organizations. For a discussion of unauthorized appropriations, see Justin Bogie, “Time to End ‘Zombie’ Appropriations,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4583, June 24, 2016, https://www.heritage.org/budget-and-spending/report/time-end-zombie-appropriations.

[7] See, for example, The Heritage Foundation, Budget Blueprint for Fiscal Year 2023, 2022, https://www.heritage.org/budget/.

[8] Natalie Sherman, “US Interest Rates Raised to Highest Level in 16 Years,” BBC News, May 4, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-65474456 (accessed August 10, 2023).

[9] The dramatic spike in 2020 and 2021 followed by a decrease in 2022 is due to the federal government’s increased expenditures during the coronavirus pandemic.

[10] For the FY 2024 edition, see U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2024, May 2023, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2024/FY24_Green_Book.pdf (accessed August 10, 2023).

[11] Reuters, “Pentagon Asks U.S. Forces Korea to Provide Equipment for Ukraine,” January 19, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/pentagon-asks-us-forces-south-korea-provide-equipment-ukraine-2023-01-19/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

[12] See Bradley Penniston, “Explainer: What Is the Pentagon’s Fourth Estate?” Defense One, updated May 12, 2021, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2020/02/what-pentagons-fourth-estate/162939/ (accessed August 11, 2023).

[13] Frederico Bartels, “Carving Up the Defense Budget,” Daily Caller, May 7, 2021, https://dailycaller.com/2021/05/07/bartels-carving-up-defense-budget/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

[14] Jared Serbu, DoD CMO Gains New Cachet as ‘Secretary of the Fourth Estate,’ Federal News Network, July 9, 2020, https://federalnewsnetwork.com/on-dod/2020/07/dod-cmo-gains-new-cachet-as-secretary-of-the-fourth-estate/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

[15] Frederico Bartels, “Congress Should Not Terminate the Pentagon’s Chief Management Officer…Yet,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 5092, July 17, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/congress-should-not-terminate-the-pentagons-chief-management-officeryet.

[16] Frederico Bartels, “Improving Defense Resourcing: Recommendations for the Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Reform,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 5257, March 24, 2022, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/improving-defense-resourcing-recommendations-the-commission-planning-programming.

[17] A good example can be seen in Secretary of Defense Mark Esper’s description of the first budget released during his tenure. See Aaron Mehta, “Mark Esper on the ‘Big Pivot Point’ that Will Define the 2022 Budget,” Defense News, February 10, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/smr/federal-budget/2020/02/10/mark-esper-on-the-big-pivot-point-that-will-define-the-2022-budget/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

[18] S. 1605, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, Public Law No. 117-81, December 27, 2021, Title X, Section 1004, https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ81/PLAW-117publ81.pdf (accessed August 11, 2023).

[19] See Appendix 1, “Commission on PPBE Reform Community Engagement,” updated as of February 21, 2023, in Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Reform, Status Update, March 2023, https://ppbereform.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PPBE-REFORM-COMMISSION-STATUS-UPDATE-MAR-2023-Public.pdf (accessed August 10, 2023).