Assessing Threats to U.S. Vital Interests

Because the United States is a global power with global interests, scaling its military power to threats requires judgments with regard to the importance and priority of those interests, whether the use of force is the most appropriate and effective way to address the threats to those interests, and how much and what types of force are needed to defeat such threats.

This Index focuses on three fundamental, vital national interests:

- Defense of the homeland;

- Successful conclusion of a major war that has the potential to destabilize a region of critical interest to the U.S.; and

- Preservation of freedom of movement within the global commons: the sea, air, outer space, and cyber-space domains through which the world conducts business.

The geographical focus of the threats in these areas is further divided into three broad regions: Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

Obviously, these are not America’s only interests. Among many others are the growth of economic freedom in trade and investment, the observance of internationally recognized human rights, and the alleviation of human suffering beyond our borders. None of these other interests, however, can be addressed principally and effectively by the use of military force, and threats to them would not necessarily result in material damage to the foregoing vital national interests. Therefore, however important these additional American interests may be, we do not use them in assessing the adequacy of current U.S. military power.

There are many publicly available sources of information on the status, capabilities, and activities of countries with respect to military power. Perhaps the two most often cited as references are The Military Balance, published annually by the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies,1 and the “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community.”2 The former is an unmatched resource for researchers who want to know, for example, the strength, composition, and disposition of a country’s military services. The latter serves as a reference point produced by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI).

Comparison of our detailed, reviewed analysis of specific countries with both The Military Balance and the ODNI’s “Annual Threat Assessment” reveals two stark limitations in these external sources.

- The Military Balance is an excellent, widely consulted source, but is primarily a count of military hardware, often without context in terms of equipment capability, maintenance and readiness, training, manpower, integration of services, doctrine, or the behavior of competitors—those that threaten the national interests of the U.S. as defined in this Index. Each edition of The Military Balance includes topical essays and a variety of focused discussions about some aspect of a selected country’s capabilities, but there is no overarching assessment of military power referenced against a set of interests, potential consequences of use, or implications for the interaction of countries.

- The ODNI’s “Annual Threat Assessment” omits many threats, and its analysis of those that it does address is limited. Moreover, it does not reference underlying strategic dynamics that are key to the evaluation of threats and that may be more predictive of future threats than is a simple extrapolation of current events.

We suspect that this is a consequence of the U.S. intelligence community’s withholding from public view its very sensitive assessments, which are derived from classified sources and/or result from analysis of unclassified, publicly available documents with the resulting synthesized insights becoming classified by virtue of what they reveal about U.S. determinations and concerns. The need to avoid the compromising of sources, methods of collection, and national security findings makes such a policy understandable, but it also causes the ODNI’s annual threat assessments to be of limited value to policymakers, the public, and analysts working outside of the government. Consequently, we do not use the ODNI’s assessment as a reference, given its quite limited usefulness, but trust that the reader will double-check our conclusions by consulting the various sources cited in the following pages as well as other publicly available reporting that is relevant to challenges to core U.S. security interests that are discussed in this section.

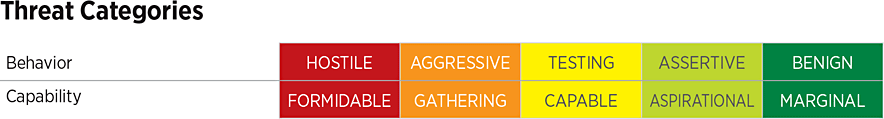

Measuring or categorizing a threat is problematic because there is no absolute reference that can be used in assigning a quantitative score. Two fundamental aspects of threats, however, are germane to this Index: the threatening entity’s desire or intent to achieve its objective and its physical ability to do so. Physical ability is the easier of the two to assess; intent is quite difficult. A useful surrogate for intent is observed behavior because this is where intent becomes manifest through action. Thus, a provocative, belligerent pattern of behavior that seriously threatens U.S. vital interests would be very worrisome. Similarly, a comprehensive ability to accomplish objectives even in the face of U.S. military power would be of serious concern to U.S. policymakers, and weak or very limited abilities would lessen U.S. concern even if an entity behaved provocatively vis-à-vis U.S. interests. It is the combination of the two—behavior and capability—that informs our final score for each assessed actor.

Each categorization used in this Index conveys a word picture of how troubling a threat’s behavior and set of capabilities have been during the assessed year. The five ascending categories for observed behavior are:

- Benign,

- Assertive,

- Testing,

- Aggressive, and

- Hostile.

The five ascending categories for physical capability are:

- Marginal,

- Aspirational,

- Capable,

- Gathering, and

- Formidable.

As noted, these characterizations—behavior and capability—form two halves of an overall assessment of the threats to U.S. vital interests.

The most current and relatable example of this interplay between behavior and capability is Russia’s brutal assault on Ukraine. Throughout its buildup of forces along its border with Ukraine during 2021, Russia consistently downplayed observers’ concerns that its actions were a prelude to war. Regardless of its protestations, however, one could not dismiss the potential for grievous harm that was inherent in Russia’s forces and their disposition. Russia’s behavior, combined with the military capability it had deployed in posture and geographic position, belied its official pronouncements.

The same thing can be said about China, Iran, and North Korea. Each country typically rejects observers’ concerns that its military activities, posturing, and investments threaten the interests of neighbors and distant competitors like the U.S., but no rational country can ignore the potential inherent in the forces these countries are fielding, the investments they are making in improving and expanding their capabilities, and the pattern of behavior they exhibit that reveals regime preferences for intimidation and coercion over diplomacy and mutually beneficial economic interaction.

It is therefore in the core interest of the United States to take stock of the capabilities and behaviors of its chief adversaries as it considers the status of its own military forces.

We always hold open the potential to add or delete from our list of threat actors. The inclusion of any state or non-state entity is based solely on our assessment of its ability to present a meaningful challenge to a critical U.S. interest during the assessed year.

Endnotes

[1] For the most recent of these authoritative studies, see International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2023: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2023), https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance (accessed June 7, 2023).

[2] See Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” February 6, 2023, https://www.odni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf (accessed June 7, 2023). Issued before 2021 as “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community,” or WWTA.