U.S. Nuclear Weapons

Michaela Dodge, PhD

To assess U.S. nuclear weapons properly, one must understand three things: their essential national security function, the growing nuclear threat posed by adversaries, and the current state of U.S. nuclear forces and their supporting infrastructure. Such an understanding helps to provide a clearer view of the state of America’s nuclear capabilities than might otherwise be possible.

The Important Roles of U.S. Nuclear Weapons

U.S nuclear weapons have played a critical role in preventing conflict among major powers in the post–World War II era. Given their ability both to deter large-scale attacks that threaten the U.S. homeland, allies, and forward-deployed troops and to assure allies and partners, nuclear deterrence has remained the number one U.S. national security mission.1 Operationally, “[s]trategic deterrence is the foundation of our national defense policy and enables every U.S. military operation around the world.”2 It is therefore critical that the United States maintain a modern and flexible nuclear arsenal that can deter a diverse range of threats from a diverse set of potential adversaries.

The more specific roles of U.S. nuclear weapons as outlined in U.S. policy have been adjusted over time. The most up-to-date applicable policy document, the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), specifies three roles for nuclear weapons:

- Deter strategic attacks;

- Assure Allies and partners; and

- Achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails.3

These roles have been consistent across U.S. post–Cold War Administrations until the Biden Administration chose to drop “Capacity to hedge against an uncertain future”4 as one of the formal roles for U.S. nuclear weapons. This omission is puzzling, particularly given the global security environment’s degradation following the 2018 NPR. The Biden Administration has not clarified whether this omission will have practical implications for U.S. nuclear operations and posture, but it is critical that the United States retain the capability to respond flexibly to negative developments in the international environment in a timely manner—a capability the nation has been struggling to sustain since the end of the Cold War.

Given the rapid evolution of a range of capabilities fielded by China, Russia, and North Korea—and increasingly by Iran—the Administration’s decision to cancel the sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) program is similarly puzzling. The Administration’s retention of the W76-2 low-yield submarine-launched nuclear warhead would seem to indicate that it recognizes the gap in regional nuclear capabilities that has left the United States at a major disadvantage against its adversaries. Adversaries have developed an array of smaller-yield weapons that provide a range of employment options, whereas the U.S. must rely almost exclusively on large-yield warheads. The SLCM-N would provide a more relevant option to U.S. leaders and thus likely serve as a more effective deterrent in these settings.

The Biden Administration emphasizes “[m]utual, verifiable nuclear arms control” as “the most effective, durable and responsible path to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our strategy and prevent their use,”5 but as former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces Policy Keith Payne points out, “[t]o claim that arms control rather than deterrence is the ‘most effective, durable and responsible path’ to preventing the employment of nuclear weapons is manifestly problematic and suggests a distorted prioritization.”6 The Biden Administration also canceled the B83 nuclear bomb, the most powerful nuclear weapon in the U.S. arsenal with a specific mission of targeting hard and deeply buried targets and an especially important capability in light of adversaries’ efforts to protect what they value.7

On the positive side, the Biden Administration refrained from implementing the “no first use” or “sole purpose” nuclear declaratory policy despite then-candidate Biden’s interest in doing so,8 reportedly because of significant objections from U.S. allies. Another positive development is the Administration’s commitment to “tailored” deterrence, or the effort to use a specific understanding of what different antagonists value and threatening those valued targets during deterrence messaging.9 As deterrence expert Greg Weaver has cogently observed, “[i]n a deterrence relationship, the adversary doesn’t just have ‘a’ vote, they have the only vote.”10 That places a premium on understanding what adversaries value and threatening it in ways that are most likely to cause them to choose restraint. The Administration also endorsed the modernization of all three legs of the nuclear triad (bombers, intercontinental-range ballistic missiles, and submarines) that was started under the Obama Administration and continued by the Trump Administration.

To achieve the objectives spelled out in the NPR, the U.S. nuclear portfolio must balance the appropriate levels of capacity, capability, variety, flexibility, and readiness. What matters most in deterrence is not what the United States thinks will be effective, but the psychological perceptions—among both adversaries and allies—of America’s willingness to use nuclear forces to defend its interests and intervene on behalf of allies. If an adversary believes it can fight and win a limited nuclear war, for instance, U.S. leaders must devise a posture that will convince that adversary that this is not possible. In addition, as the 2022 NPR appropriately recognizes, military roles and requirements for nuclear weapons will differ from adversary to adversary based on each country’s values, strategy, force posture, and goals.

The United States also extends its nuclear umbrella to 33 allies that rely on America to defend them from large-scale attacks and existential threats from adversaries. This additional responsibility imposes requirements for the U.S. nuclear force posture that go beyond defense of the U.S. homeland.

U.S. nuclear forces underpin the broad nonproliferation regime by assuring allies—including NATO, Japan, South Korea, and Australia—that they can forgo development of their own nuclear weapons. Erosion of America’s nuclear credibility could lead a country like Japan or South Korea to pursue an independent nuclear option, in which case the result could be a negative impact on stability across the region. Regrettably, there are signs that the credibility of U.S. assurances is in fact eroding. For example, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol recently stated that if the nuclear threat from North Korea continues to grow, his country “would consider building nuclear weapons of its own” and could do so “pretty quickly, given our scientific and technological capabilities.”11

In addition to deterrence and assurance, the United States historically has committed to achieving its political and military objectives if nuclear deterrence fails by having the will to use its nuclear weapons in war. This also contributes to deterrence both by convincing an adversary that it could not start and win a nuclear war and by minimizing U.S. subjection to nuclear coercion by peer nuclear adversaries. U.S. forces must therefore be survivable and postured to engage their targets successfully if deterrence fails and it becomes necessary to use nuclear weapons.

Understanding Today’s Multipolar Global Threat Environment

Any assessment of nuclear capabilities requires an understanding of the threat environment, as any U.S. strategy or force posture must account for the threat it is meant to deter or defeat. For the first time in its history, the United States faces two nuclear peer competitors at once—Russia and China.12 This differs drastically from the paradigm based on the bilateral U.S.–Soviet deterrence relationship during the Cold War. Although China also possessed nuclear weapons, its security interests were largely domestic rather than global. It maintained a limited nuclear capability, but the nature of U.S.–China relations was much different from the global contest between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

This situation has changed with China’s rise as an economic power with global influence and interests and its corresponding investments in power projection capabilities that include a modern nuclear weapons portfolio of increasing size. Unfortunately, China was not party to the gradual evolution of nuclear deterrence theory shaped by the U.S.–Soviet dynamic, nor has it ever been party to the various agreements governing nuclear matters between the Cold War competitors. Consequently, China operates with a different paradigm and introduces a third, unknown element into nuclear deterrence calculations.

A multipolar nuclear threat environment presents new and complex challenges. As a result, the assessment in this Index must be weighed against this emerging nuclear threat.

Russia is engaged in an aggressive nuclear expansion, having added several new nuclear systems to its arsenal since 2010. The United States is only beginning to modernize its existing nuclear systems, but Russia’s modernization effort is about 89 percent complete.13 Russia also is developing such “novel technologies” as a nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed cruise missile, as well as a nuclear-armed unmanned underwater vehicle, and is arming delivery platforms with nuclear-tipped hypersonic glide vehicles.14 Russia suspended the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) in February 2023, and the State Department reports that it is unable to verify that Russia is in compliance with the Treaty.15

In addition, Russia maintains a stockpile of at least 2,000 non-strategic nuclear weapons, unconstrained by any arms control agreement.16 Defense Intelligence Agency Director Lieutenant General Robert Ashley has said that Russia is expected to increase this category of nuclear weapons—a category in which it “potentially outnumber[s]” the United States by 10 to 1.17 This disparity is of special concern because Russia’s recent nuclear doctrine indicates a lower threshold for use of these tactical nuclear weapons. Russia has also been engaging in nuclear saber-rattling over its war on Ukraine, issuing both subtle and blatant nuclear threats in an attempt to coerce the West into not providing Ukraine with certain weapons systems and not engaging directly in the conflict.18

China is engaged in what Admiral Charles A. Richard, former Commander of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), has described as a “breathtaking expansion” of its nuclear capabilities as part of a strategic breakout that will require immediate and significant shifts in Department of Defense (DOD) capabilities and force posture.19 According to Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy John Plumb, China has established “a nascent nuclear triad” and, if its nuclear weapons modernization continues at its current pace, “could field an arsenal of about 1,500 warheads by 2035,”20 which would be more than three times as large as its current estimated inventory of more than 400 warheads. In February 2023, current STRATCOM Commander General Anthony J. Cotton notified Congress that China now has more intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launchers than the United States has.21

China is deploying hundreds of theater-range ballistic missiles that can strike U.S. bases and allied territory with precision, and many of these missiles can be fitted with either conventional or nuclear warheads. Beijing is also testing nuclear-capable hypersonic weapons including one that orbited the globe on a fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS) before being released to glide to its target.22 The DOD reports that “[t]he PLA is implementing a launch-on-warning posture, called ‘early warning counterstrike’…where warning of a missile strike leads to a counterstrike before an enemy first strike can detonate.”23

Combined with China’s refusal to discuss its forces or intent with the United States, this shift in posture increases the potential for mistakes and miscalculations.24 Unlike the United States and Russia, which share a long history of communicating through arms control discussions and military-to-military contacts to reduce these types of risks, China has not participated in these measures. In fact, China refused to answer U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s telephone call following the U.S. shootdown of China’s spy balloon in February 2023.25 The magnitude of China’s nuclear expansion and qualitative upgrades has led senior U.S. leaders to conclude that China has become a nuclear peer to the United States and Russia and eventually could surpass U.S. nuclear capabilities.26 China no longer has a minimum deterrence capability; instead, it “possesses the capability to employ any coercive nuclear strategy today.”27

In addition to having to contend with two nuclear peers, the United States must account for the nuclear threats posed by smaller state adversaries. North Korea is advancing its nuclear weapons and missile capabilities. It continues to produce fissile material to build new nuclear weapons and has developed a new “monster” ICBM that allegedly is able to carry multiple warheads.28 North Korea conducted an ICBM test in February 2023 in addition to testing what it claimed was a hypersonic missile during the past year.29 It also revealed what appear to be tactical nuclear weapons that could be mounted on short-range missiles and used to threaten South Korea.30

In addition to being the world’s principal state sponsor of terrorism, Iran has managed to produce “high enriched uranium (HEU) particles containing up to 83.7% U-235”31 and reportedly has acquired enough fissile material to produce a nuclear bomb.32 A nuclear-armed Iran would have significant implications both for stability in the Middle East and for U.S. nonproliferation goals.

Finally, given the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in deterring strategic attacks (for example, attacks featuring the massive use of conventional, chemical, or biological weapons), it is important to consider non-nuclear threats posed by adversaries.

- Both Russia and China are deploying advanced conventional capabilities like conventionally armed hypersonic missiles and even conventionally armed cruise missiles that are capable of striking the U.S. homeland.33

- The United States “cannot certify” that China is in compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and has certified that both Iran and Russia are in noncompliance with the CWC.34

- The United States has similar compliance concerns regarding the PRC’s and Iran’s adherence to the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) and has found Russia to be in noncompliance with its BWC obligations.35

- North Korea also is in noncompliance with the BWC and “probably is capable of weaponizing BW agents with unconventional systems such as sprayers and poison pen injection devices, which have been deployed by North Korea for delivery of chemical weapons.”36 It also is one of four states that “have neither ratified nor acceded to the CWC and, therefore, are not States Parties to the Convention.”37

Since the effects of these types of attacks can be strategic in nature and the United States does not possess chemical or biological weapons of its own, U.S. nuclear weapons will continue to play a role in deterring these threats.

Current U.S. Nuclear Capabilities and Maintenance Challenges

To assess U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities, one needs to understand the current state of those capabilities and the challenges associated with maintaining them. The United States maintains a force posture based on the guidelines set forth by the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty signed with Russia in 2010.

To abide by New START limits, the United States maintains 14 nuclear-armed Ohio–class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), each of which can be armed with as many as 20 Trident II D5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs); 400 single-warhead Minuteman III ICBMs deployed among 450 silos; and about 60 nuclear-capable B-52 and B-2 bombers that can be armed with gravity bombs or air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs).38 As of May 12, 2023, the United States was deploying 1,419 warheads under New START counting rules, which count each nuclear-capable bomber as one warhead.39 Additionally, the United States maintains about 200 B61 tactical gravity bombs. About 100 of these bombs are deployed in Europe, and the remaining 100 are in central storage in the United States as backup, including for contingency missions not in Europe.40

The United States is working to modernize these nuclear forces, which are aged far beyond their original design lifetimes. U.S. nuclear delivery systems, warheads, and supporting infrastructure were all developed during the Cold War and have very little if any margin for further life extension or modernization delays. As summed up by Admiral Richards:

We are at a point where end-of-life limitations and the cumulative effects of underinvestment in our nuclear deterrent and supporting infrastructure leave us with no operational margin. The Nation simply cannot attempt to indefinitely life-extend leftover Cold War weapon systems and successfully support our National strategy. Pacing the threat requires dedicated and sustained funding for the entire nuclear enterprise and NC3 Next Generation modernization must be a priority.41

Faced with this set of circumstances, the United States must contend with three overarching challenges:

- The need to modernize its delivery systems and sustain the viability of its nuclear warheads,

- The need to refurbish an aging nuclear weapons infrastructure, and

- The need to recruit and train talented personnel to replace an aging workforce.

The current nuclear modernization program dates from 2010. The assumptions then were that Russia was no longer an adversary and that the potential for great-power conflict was low.42 Events over the past decade have proved these assumptions wrong. The extraordinary technical and geopolitical developments being realized today—China’s nuclear breakout and Russia’s demonstrated aggression, nuclear expansion, and nuclear coercion—were generally not anticipated as the Obama Administration went about finalizing the planned U.S. nuclear force structure for the coming decades.43

The United States is planning to replace its nuclear forces largely on a one-to-one basis instead of expanding or diversifying the current arsenal. In some cases, the current modernization program reduces potential capacity. The Columbia–class nuclear submarine, for example, will have eight fewer missile tubes than its predecessor, the Ohio–class—not to mention two fewer submarines.44 The only significant change proposed in the 2010 nuclear modernization plans were the Trump Administration’s decisions to deploy W76-2 low-yield warheads for the SLBMs in 2020 (endorsed by the Biden Administration) and the proposed nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), the latter of which the Biden Administration has attempted to defund despite congressional support for the project.

To provide a hedge against adverse changes in a geopolitical situation like today’s, as well as against failures in the U.S. stockpile, the United States preserves an upload capability that allows it to increase the number of nuclear warheads on each type of its delivery vehicles. The U.S. Minuteman III ICBM, for example, is currently deployed with only one Mk12A/W78 warhead, but it can carry as many as three; the Trident II SLBM can carry several warheads at once; and the B-52 bomber can carry additional cruise missiles.45

The reduced number of missile tubes on the future Columbia–class SSBN will in turn reduce the strategic submarine force’s upload capacity unless more submarines are procured. Overall, U.S. hedge capacity is limited as uploading warheads onto the Minuteman III missiles would prove to be both time-consuming and costly. Exploiting the bomber upload capacity during peacetime would present a difficult challenge because bombers currently do not remain on alert. Uncertainty as to whether the United States will have enough deployable warheads or air-launched cruise missiles will remain another potential impediment to upload capacity.

The United States also maintains an inactive stockpile that includes near-term hedge warheads that “can serve as active ready warheads within prescribed activation timelines” and reserve warheads that can provide “a long-term response to risk mitigation for technical failures in the stockpile.”46

The United States has not designed or built a nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War. Instead, the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) uses life-extension programs (LEPs) to extend the service lives of existing nuclear warheads in the stockpile, some of which date back to the 1960s. While LEPs replace or upgrade most components in a nuclear warhead, all warheads will eventually need to be replaced because their nuclear components—specifically, plutonium pits that comprise the cores of warheads—are also subject to aging.47 The United States is the only nuclear state that lacks the capability to produce plutonium pits in quantity. The NNSA’s fiscal year (FY) 2024 budget request notes a 10 percent increase for “Weapons Activities” to “continue restoring production capability, including the capability to produce 80 plutonium pits per year (ppy) as close to 2030 as possible.”48

Demographic challenges within the nuclear weapons labs also affect the ability of the U.S. to modernize its warhead stockpile. Because most scientists and engineers with practical hands-on experience in nuclear weapons design and testing are retired, the certification of weapons that were designed and tested as far back as the 1960s depends on the scientific judgment of designers and engineers who have never been involved in either the testing or the design and development of nuclear weapons. In recent years, the NNSA has invested in enabling its workforce to exercise critical nuclear weapons design and development skills—skills that have not been fully exercised since the end of the Cold War—through the Stockpile Readiness Program. These skills must be available when needed to support modern warhead development programs for SLBMs and ICBMs.

The shift in emphasis away from the nuclear weapons mission after the end of the Cold War led to a diminished ability to conduct key activities at the nuclear laboratories. According to NNSA Administrator Jill Hruby, “workforce recruiting and retention programs have helped us turn the tide of attrition post-Covid,” and the budget request reflects the Administration’s commitment to a “safe, secure, and reliable stockpile.”49 The NNSA continues to struggle with infrastructure recapitalization, as “[m]ore than 60 percent [of its facilities] are beyond their life expectancy, with some of the most important dating back to the Manhattan Project.”50 Because of this neglect, NNSA must now recapitalize the nuclear weapons complex at the same time the nation faces the need to modernize its aging nuclear warheads.

In recent years, bipartisan congressional support for the nuclear mission has been strong, and nuclear modernization has received additional funding. Preservation of that bipartisan consensus will be critical as these programs mature and begin to introduce modern nuclear systems to the force.

In FY 2023, the Biden Administration, supported by Congress, advanced the comprehensive modernization program for nuclear forces that was initiated by President Barack Obama and continued by the Trump Administration. Despite some opposition, Congress funded the two previous Presidents’ budget requests for these programs as well. Because such modernization activities require consistent, stable, long-term funding commitments, this continued bipartisan support has been critical.

The NNSA received $22.2 billion in FY 2023, which was about $1.5 billion more than it received in FY 2022 and included full funding for major efforts like modernization of plutonium pit production and five warhead modernization programs. The FY 2024 budget would continue these efforts with an NNSA topline of $23.8 billion.51 The FY 2024 budget also supports modernization programs to replace the triad, including the Sentinel ICBM weapon system; Long Range Stand Off Weapon cruise missile (LRSO); Columbia–class nuclear submarine; and B-21 Raider bomber.

In FY 2023, Congress also provided funding to begin research and development on a nuclear-armed, sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), which, driven by the worsened security environment with Russia and China, had been proposed in the 2018 NPR.52 However, the Biden Administration removed funding for this capability in its FY 2023 and FY 2024 budget requests. Despite the Administration’s opposition, the Congress authorized $25 million for the program on a bipartisan basis in the FY 2023 defense budget.53

Assessing U.S. Nuclear Force Capacity

To assess the military services, other sections in this Index use a combination of government strategies or assessments and historical data based on capacity and capabilities that the United States has needed to fight wars in the past. For example, using data from four previous wars and strategies over time, this Index assesses Army Brigade Combat Team (BCT) capacity based on a total of 50 BCTs required to deal with two major regional conflicts.54

Assessing the capacity of U.S. nuclear weapons, however, presents several serious difficulties. Because a nuclear war has never been fought, there are no historical data that can be used to determine a baseline for how much nuclear capability the United States needs. The only time nuclear weapons have been used was in 1945 when the U.S. bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but that does not provide any information on how much nuclear capability is needed because the United States was the only nuclear-weapon state and did not yet maintain a functioning nuclear arsenal.

Moreover, since deterrence depends on an adversary’s perception of a threat as credible, it is very difficult to quantify how many warheads, and on how many and what types of platforms, the United States needs to deter an adversary. Deterrence requires (1) an understanding of what an adversary values and (2) the ability to threaten that adversary so credibly that he refrains from acting against U.S. interests, thereby jeopardizing what he values. The size of the nuclear force that the U.S. needed to deter the Soviet Union during the Cold War is not a good approximate metric because today’s environment is much different and there are more nuclear-armed powers than there were then.55

Nevertheless, it is possible to draw some conclusions about the adequacy of the current U.S. nuclear force’s size and structure. A force that is sized to deter only one nuclear peer is not likely to be sufficient to deter two nuclear peers—in this case, both Russia and China, particularly given their emerging cooperative relationship. Consensus during the early years of the Obama Administration centered around the assessment that Russia was the primary nuclear threat, that China would likely not alter its minimum deterrence posture, and that nuclear proliferation in Iran or an India–Pakistan nuclear conflict would dominate future nuclear threats.56 Then-STRATCOM Commander General Kevin Chilton testified in 2010 that “the arsenal that we have is exactly what is needed today to provide the deterrent.”57 Given the changes of the past 10 years, however, a nuclear force that was capable of countering the threats we faced in 2010 is not likely to be capable of countering the threats we will face in the near future.

There is a direct relationship between adversary capabilities and what the U.S. needs for deterrence. Fundamental to the concept of deterrence is the ability to hold at risk the assets that our adversaries value most, including their nuclear forces and accompanying infrastructure. For deterrence to be credible, the United States must maintain the numbers and types of survivable nuclear weapons it needs to convince adversaries that it can strike valued targets if necessary. Given the increase in targets resulting from China’s, Russia’s, and North Korea’s nuclear expansion and their potentially cooperative relationship against U.S. and allied interests, the United States will likely have to increase the number of its operationally deployed nuclear weapons.

This deficiency in capacity is particularly acute in the category of non-strategic nuclear weapons: short-range, typically lower-yield nuclear weapons that can be deployed to a region of conflict as opposed to ICBMs launched from the homeland or SSBNs that remain at sea. Russia maintains an arsenal of about 2,000 non-strategic nuclear weapons. China maintains an arsenal of hundreds of nuclear-capable medium-range to intermediate-range missiles deployed in the Indo-Pacific. Reportedly, the United States deploys about 100 tactical weapons in NATO states and no nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific.

The 2018 NPR studied these disparities and assessed that the United States needed two supplemental capabilities—the W76-2 and SLCM-N—to rectify this imbalance. The United States fielded the W76-2, but the future of the SLCM-N remains uncertain. Meanwhile, this disparity has worsened since the 2018 NPR. In April 2022, Admiral Richard wrote in a letter to Congress that “the current situation in Ukraine and China’s nuclear trajectory convinces me a deterrence and assurance gap exists.”58

Despite this assessment, however, current STRATCOM Commander General Anthony Cotton has stated only that an SLCM-N “is one of several possible nuclear or conventional capabilities the U.S. could develop to enhance strategic deterrence.”59 Other Biden Administration officials, including Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Secretary of the Navy Admiral Carlos Del Toro, have testified in favor of cancelling the program.60 On the other hand, the SLCM-N has won support from:

- Admiral Charles A. Richard, former Commander, U.S. Strategic Command;

- General Mark A. Milley, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff;

- Admiral Christopher W. Grady, Vice Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff;

- General Tod D. Wolters, former Commander, U.S. European Command; and

- Admiral Michael M. Gilday, Chief of Naval Operations.61

The combination of what Admiral Richard calls a “deterrence and assurance gap” and the sheer numerical difference between the United States and its adversaries in non-strategic and intermediate-range forces would certainly seem to justify a poor score for the capacity of America’s nuclear force, but there is a question that remains unanswered: How much more does the United States need to account for the drastic change in the Chinese nuclear threat, Russia’s continuing expansion, and a growing nuclear arsenal in North Korea? In addition to the inherent constraints on determining a baseline for nuclear weapons capacity, it would be hard to determine what an ideal force posture would look like in a three-party nuclear dynamic.

For now, according to Admiral Richard, the United States is “furiously” rewriting deterrence theory to account for this dynamic—a difficult exercise because “[e]ven our operational deterrence expertise is just not what it was at the end of the Cold War. So we have to reinvigorate this intellectual effort.”62 The process is ongoing, but at a minimum, the United States should retain one of its primary sizing metrics for its force posture: being able to withstand an adversary’s first strike and still respond in a way the adversary would deem unacceptable. In an environment that includes two peer competitors rather than just one, the United States will need to decide whether the planned nuclear force can still meet that requirement, especially given the possibility of Russian and Chinese cooperation or coordination.

This Index therefore concludes that U.S. nuclear weapons capacity is insufficient to face two nuclear peers at once but does not assign a score in this category. This may change in future editions.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons Assessment

In rating America’s military services, this Index focuses on capacity, capability, and readiness. In assessing our nuclear forces, however, this Index focuses on several components of the existing nuclear weapons enterprise. This enterprise includes warheads, delivery systems, and the physical infrastructure that maintains U.S. nuclear weapons. It also includes the talent of people—the nuclear designers, engineers, manufacturing personnel, planners, maintainers, and operators who help to ensure the U.S. nuclear deterrent—and additional elements like nuclear command and control; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); and aerial refueling, all of which also play a major role in conventional operations.

Many factors make such an assessment difficult, but two stand out.

- There is a lack of detailed publicly available data about the readiness of nuclear forces, their capabilities, and the reliability of the warheads that delivery systems carry.

- Many components that comprise the nuclear enterprise are also involved in supporting conventional missions. For example, U.S. strategic bombers perform a significant conventional mission and do not fly airborne alert with nuclear weapons today as they did routinely during the 1960s. Thus, it is hard to assess whether any one piece of the nuclear enterprise is sufficiently funded, focused, and/or effective with regard to the nuclear mission.

An additional challenge is the nature of media coverage. When information surfaces in the media, it is usually news of problems and mishaps; excellence is par for the course and therefore apparently not worth the effort it would take to report on it.

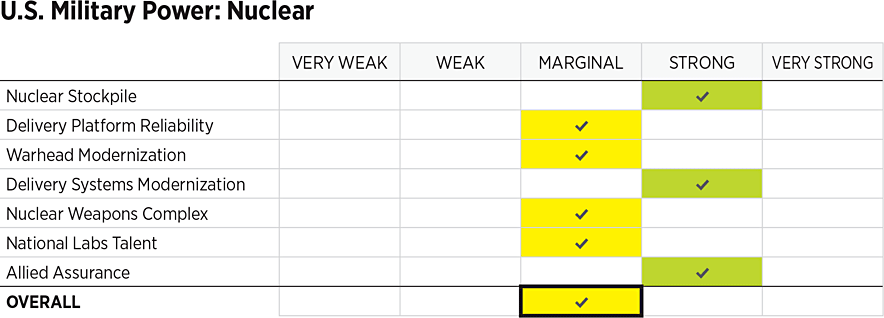

With these difficulties in mind, this assessment considers seven factors that are deemed the most important elements of the nuclear weapons enterprise:

- Reliability of the current U.S. nuclear stockpile,

- Reliability of current U.S. delivery systems,

- Nuclear warhead modernization,

- Nuclear delivery systems modernization,

- Nuclear weapons complex,

- Personnel challenges within the national nuclear laboratories, and

- Allied assurance.

These factors are judged on a five-grade scale that ranges from “very strong” (defined as meeting U.S. national security requirements or having a sustainable, viable, and funded plan in place to do so) to “very weak” (defined as not meeting current security requirements and with no program in place to redress the shortfall). The other three possible scores are “strong,” “marginal,” and “weak.”

Reliability of Current U.S. Nuclear Stockpile Score: Strong

U.S. warheads must be safe, secure, effective, and reliable. The Department of Defense defines reliability as “the probability that a weapon will perform in accordance with its design intent or military requirements.”63 Since the cessation of nuclear testing in 1992 and the follow-on debate about the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (rejected by the Senate in 1999), reliability has been assessed and maintained through the NNSA’s Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP), which consists of an intensive warhead surveillance program; non-nuclear experiments (experiments that do not produce a nuclear yield); sophisticated calculations using high-performance computing; and related annual assessments and evaluations. America and its allies must have high confidence that U.S. nuclear warheads will perform as expected.

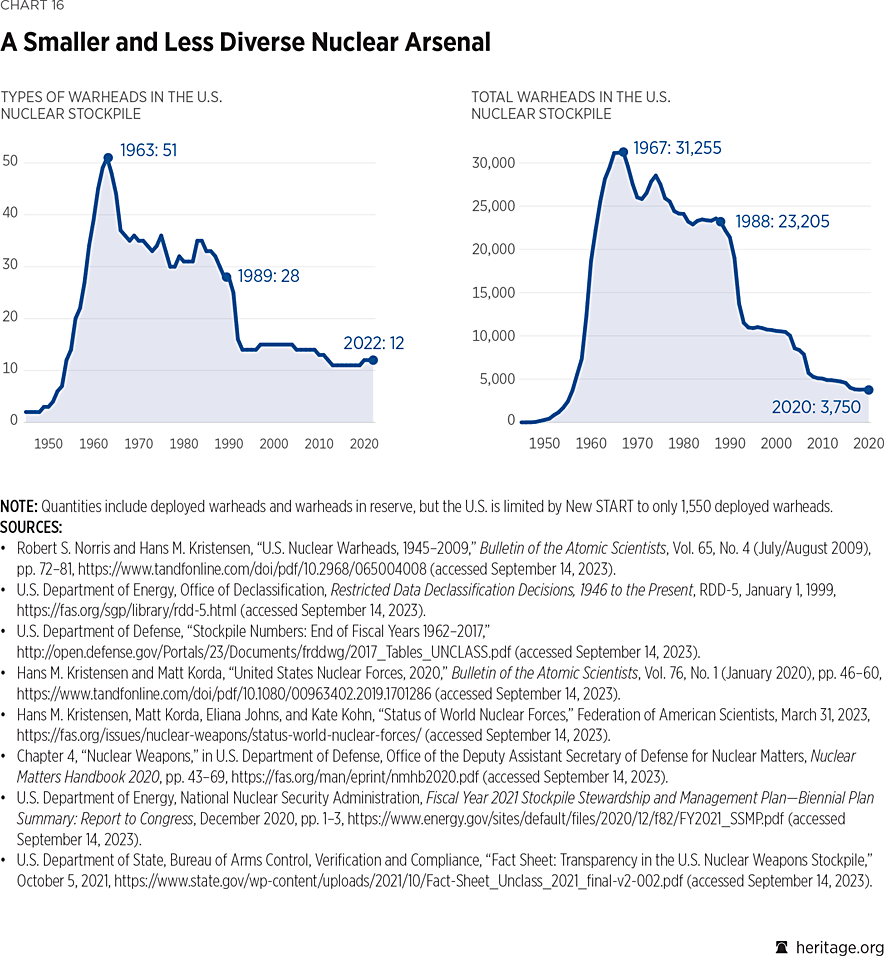

Over time, the number and diversity of nuclear weapons in the stockpile have decreased. The result is a smaller margin of error if all of one type are affected by a technical problem that might cause a weapon type or its delivery system to be sidelined for repair or decommissioned. Despite generating impressive amounts of knowledge about nuclear weapons physics and materials chemistry, the United States could find itself surprised by unanticipated long-term effects on a nuclear weapon’s aging components. “The scientific foundation of assessments of the nuclear performance of US weapons is eroding as a result of the moratorium on nuclear testing,” argue John Hopkins, nuclear physicist and a former leader of the Los Alamos National Laboratory’s nuclear weapons program, and David Sharp, former Laboratory Fellow and a guest scientist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory.64

The United States currently has a safe and secure stockpile, but concerns about overseas storage sites, potential problems introduced by improper handling, or unanticipated effects of aging could compromise the integrity or reliability of U.S. warheads. The nuclear warheads themselves contain security systems that are designed to make it difficult if not impossible to detonate a weapon without proper authorization. Some U.S. warheads have modern safety features that provide additional protection against accidental detonation; others do not because those safety features could not be incorporated absent yield-producing experiments.

Grade: Absent an ability to conduct yield-producing experiments, the national laboratories’ assessment of weapons reliability, based on the full range of surveillance, scientific, and technical activities carried out in the NNSA Stockpile Stewardship Program, depends on the expert judgment of the laboratories’ directors and the weapons scientists and engineers on their staffs. This judgment is based on experience, non-nuclear experimentation, and extensive modeling and simulation. It does not benefit from data that could be obtained through yield-producing experiments or nuclear weapons testing, which was used in the past to validate that warheads performed as designed and to certify potential fixes to any problem identified by such testing.

The United States maintains the world’s most advanced Stockpile Stewardship Program and continues to make scientific and technical advances that help to certify the stockpile. The FY 2024 budget request for the Stockpile Research, Technology, and Engineering program is $3.2 billion, approximately $100 million of which “is for the Z-pinch Experimental Underground System (Zeus) Test Bed Facilities Improvement Project and the Advanced Sources and Detectors Scorpius radiography capability, which provide the main capabilities within Enhanced Capabilities for Subcritical Experiments at the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS).”65

Such advanced capabilities can help the NNSA to certify the stockpile more accurately and without testing, but according to Admiral Richard, confidence in the stockpile requires two other components in addition to the Stockpile Stewardship Program:

[Y]ou have to have a flexible and modern stockpile, which means we need to move past life extensions, which we have been doing for 30 years, and move into refurbishments, which is where NNSA is about to go. And…[y]ou have to have a modern, responsive, and resilient infrastructure, and we have delayed too long, in my opinion, giving NNSA the resources necessary to do that piece.66

To assess the reliability of the nuclear stockpile annually, each of the three nuclear weapons labs (the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratory) reports its findings with respect to the safety, security, and reliability of the nation’s nuclear warheads to the Secretary of Energy and the Secretary of Defense, who then brief the President. Detailed classified reports are provided to Congress as well. The Commander of U.S. Strategic Command also assesses overall nuclear weapons system reliability, including the reliability of both warhead and delivery platforms.

In spite of concerns about aging warheads, according to the NNSA’s Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) for FY 2023:

In 2021, DOE/NNSA…conducted surveillance activities for all weapon systems using data collection from flight tests, laboratory tests, and component evaluations to assess stockpile reliability without explosive nuclear testing, which culminated in completion of all annual assessment reports and generation of laboratory director letters to the President.67

Additionally, when asked in a congressional hearing whether she “agree[s] that there is not a current or foreseeable need for the United States to resume explosive nuclear testing that produces nuclear yields,” Administrator Hruby responded, “Yes…I do. And I would just go further to say our entire Stockpile Stewardship Program is designed around the principal [sic] that we will make sure we understand weapons enough so that we do not have to test.”68

Based on the results of the existing method used to certify the stockpile’s effectiveness, we grade the U.S. stockpile conditionally as “strong.” This grade, however, will depend on whether support for an adequate stockpile, both in Congress and in the Administration, remains strong.

Reliability of Current U.S. Delivery Systems Score: Marginal

Reliability encompasses strategic delivery vehicles in addition to the warhead. For ICBMs, SLBMs, and ALCMs, this requires a successful missile launch, including the separation of missile boost stages, performance of the missile guidance system, separation of the reentry vehicles from the missile post-boost vehicle, and accuracy of the final reentry vehicle in reaching its target.69 It also entails the ability of weapons systems (cruise missiles, aircraft carrying bombs, and reentry vehicles) to penetrate adversary defensive systems and reach their targets.

The United States conducts flight tests of ICBMs and SLBMs every year to ensure the reliability of its delivery systems with high-fidelity “mock” warheads. Anything from faulty electrical wiring to booster separations could degrade the reliability and safety of the U.S. strategic deterrent. U.S. strategic long-range bombers also regularly conduct exercises and receive upgrades to sustain a demonstrated high level of combat readiness. The Air Force tested the AGM-86B ALCM, launched from the B-52H bomber, most recently in 2017.70 The DOD must upgrade existing platforms and develop their replacement programs simultaneously, sometimes in concurrence with the NNSA’s work on nuclear warheads.

Grade: In July 2018, the Air Force conducted its first unsuccessful ICBM test since 2011,71 but it has conducted several successful tests since then, including a test in August 2020 that launched a missile armed with three reentry vehicles72 and its most recent test, which was conducted in April 2023.73 The May 2021 test was marred by a ground abort before launch, and this has provoked speculation about the reliability of the Minuteman III missile as it approaches its retirement, which is scheduled to begin in 2029.74 Additionally, the DOD canceled a Minuteman III test scheduled for March 2022 “in a bid to lower nuclear tensions with Russia.” An SLBM test in 2022 was successful.75

To the extent that data from these tests are publicly available, they provide objective evidence of the delivery systems’ reliability and send a message to U.S. allies and adversaries alike that U.S. systems work and that the U.S. nuclear deterrent is ready if needed. The aged systems, however, occasionally have problems, as evidenced by the failed July 2018 and May 2020 Minuteman III launches.

The evidence indicates that some U.S. delivery systems may have difficulty penetrating an adversary’s advanced defensive systems. Because of its obsolescence against Russian air defense systems, for example, the B-52H bomber already no longer carries gravity bombs.76 Despite the fact that the ALCM passed its most recent public test in 2017, then-STRATCOM Commander General John Hyten has stated that because of its age, “it’s a miracle that [the missile] can even fly” and that the current ALCMs “do meet the mission, but it is a challenge each and every day.”77 Other U.S. systems suffer from similar challenges. Admiral Richard has stated that “I need a weapon that can fly and make it to the target. Minuteman-III is increasingly challenged in its ability to do that.”78

As Russian and Chinese air and missile defenses and other anti-platform capabilities advance, the challenge for U.S. offensive systems will become greater unless the United States deploys modernized delivery systems. In addition to advanced air defense systems like the S-400, which contributed to the decision that the B-52H bomber should no longer carry gravity bombs, both Russia and China are placing a greater emphasis on long-range ballistic missile defense. Russia is modernizing its long-range interceptors—and reportedly has dozens more than the United States has—and China’s missile defense capabilities, while mostly focused on regional threats, “appear to be developing towards countering long-range missiles.”79 As U.S. delivery systems approach obsolescence, adversary air and missile defense increasingly calls into question the ability of U.S. weapons to strike their targets. The Biden Administration’s decision to retire the B83 nuclear warhead potentially leaves the United States with a gap in its ability to reach adversaries’ hard and deeply buried targets.

Both adversary defenses and system aging will continue to affect delivery platform reliability until platforms are replaced. Adversary improvements in defensive systems and decisions by the current Administration to cancel, curtail, or delay delivery platform modernization programs combine to lower the score for delivery systems reliability in this year’s edition of the Index from “strong” to “marginal.”

Nuclear Warhead Modernization Score: Marginal

During the Cold War, the United States focused on designing and developing modern nuclear warheads to counter Soviet advances and modernization efforts and to leverage advances in our understanding of the physics, chemistry, and design of nuclear weapons. Today, the United States focuses on extending the life of its aging stockpile rather than on fielding modern warheads while trying to retain the skills and capabilities needed to design, develop, and produce such warheads. Relying only on sustaining the aging stockpile could increase the risk of failure caused both by aging components and by not exercising critical skills. It also could signal to adversaries that the United States is less committed to nuclear deterrence.

Adversaries and current and future proliferators are not limited to updating Cold War designs and can seek designs outside of U.S. experiences, taking advantage of more advanced computing technologies and scientific developments that have evolved since the end of the Cold War. Other nations can maintain their levels of proficiency by developing new nuclear warheads.80 In 2020, the Department of State reported that “Russia has conducted nuclear weapons experiments that have created nuclear yield and are not consistent with the U.S. ‘zero-yield’ standard” and that there is evidence of China’s potential lack of adherence to this standard as well.81 In 2023, the department noted that “concerns remain about the nature of both China and Russia’s adherence to their respective moratoria.”82

Fortunately, the NNSA has made noticeable improvements in this category in recent years. Since 2016, Congress has funded the Stockpile Responsiveness Program (SRP) to “exercise all capabilities required to conceptualize, study, design, develop, engineer, certify, produce, and deploy nuclear weapons.”83 Congress funded the SRP at $70 million in FY 2020, FY 2021, and FY 2022.84 The FY 2023 enacted level was $63.7 million, and the Administration is requesting $69.8 million (an increase of $6.1 million) for FY 2024.85 The SRP has demonstrated some important accomplishments in ensuring critical skills retention, and scientists at the national labs have responded to it with enthusiasm.

Ongoing work at the national labs to design nuclear warheads could build on the SRP’s success. Starting in FY 2021, Congress has appropriated funding for the W93/Mark 7 warhead program, which will replace the W76-1 and W88 warheads carried by the Trident II D5 SLBMs.86 The final amount enacted for FY 2021 was $53,000,000.87 The program was funded at a level of $241 million in FY 2023 and entered its second phase (Feasibility Study and Design Options) in February 2022. The FY 2024 request for $390 million reflects the activities associated with Phase 2 and “improved cost estimates.”88 The NNSA is also developing the W87-1 warhead for the Sentinel missile, which is a modification of the existing W87-0 design.

These programs may allow American engineers and scientists to improve previous designs, including meeting evolving military requirements (for example, adaptability to emerging threats and the ability to hold hard and deeply buried targets at risk). Future warheads could improve reliability while also enhancing the safety and security of American weapons, but the question remains: How much of this work can be done without yield-producing experiments? The nuclear enterprise displayed improved flexibility when it produced the W76-2 warhead, a low-yield version of the W76 warhead. The W76 warhead was modified within a year to counter Russia’s perception of an exploitable gap in the U.S. nuclear force posture.

The ability to produce plutonium pits, which compose the core of all nuclear weapons, will be critical to warhead modernization efforts. The NNSA currently cannot produce plutonium pits at scale and is undergoing an effort to restore this capability with a statutory requirement to produce 80 pits per year by 2030—a requirement that the NNSA will not be able to meet. The new goal has shifted to somewhere from the first quarter of FY 2032 to the fourth quarter of FY 2035.89 It is planned that “the W87-1 program and subsequent modernization programs” will use these new pits.90

Grade: Before the score for this category can move up to “strong,” the NNSA, with support from Congress, will need to achieve enough progress with the W93/Mk 7 and W87-1 and minimize delays in pit production. Delays in pit production could require modern warheads to use older pits, further jeopardizing both the functioning of those systems and the credibility of the U.S. deterrent. The NNSA eventually will also need to begin programs for future land-based, sea-based, and air-delivered warheads, all of which currently remain notional, to succeed the current programs beyond 2030.91

Moreover, future assessments will need to examine whether the NNSA’s current warhead modernization effort is sufficient to address the increasing threat. For instance, despite Russian progress in hardening and deeply burying facilities to withstand strikes by current U.S. weapons, an earth-penetrating warhead is not part of the NNSA’s warhead modernization plan.92 The Biden Administration’s proposal to cancel the plan, which would keep the B83 gravity bomb (currently the only warhead capable of striking hard and deeply buried targets) beyond its planned retirement, could create a capability gap.93

For now, the score for this category remains at “marginal.”

Nuclear Delivery Systems Modernization Score: Strong but Trending Toward Marginal

All U.S. delivery systems were built during the Cold War and are overdue for replacement. The Obama Administration, in consultation with Congress, initiated a plan to replace current triad delivery systems. President Donald Trump advanced this modernization program with bipartisan support from Congress. Under this program:

- The Navy is fully funding the Columbia–class submarine to replace the Ohio–class submarine;

- The Air Force is funding the B-21 Raider Long-Range bomber, which will replace conventionally armed bombers before the new aircraft is certified to replace nuclear-capable bombers;

- The Long-Range Standoff weapon will replace the aging ALCM;

- Existing Minuteman III ICBMs are expected to remain in service beyond the end of the decade—50 years after their intended lifetime—and to be replaced by the Sentinel weapon system beginning in 2029;

- Existing Trident II D5 SLBMs have been life-extended to remain in service until 2042 through the end of the last Ohio–class submarine’s lifetime; and

- The F-35 will replace the existing F-15E Dual Capable Aircraft that will carry the B61-12 gravity bomb.94

These programs face high risks of delay. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported that the “Sentinel is behind schedule due to staffing shortfalls, delays with clearance processing, and classified information technology infrastructure challenges” and “is experiencing supply chain disruptions, leading to further schedule delays.”95 Moreover, these programs are entering a new phase of risk as they move from initial research and development to testing96 and then procurement.

These scheduling risks are especially dangerous because years of deferred recapitalization have left modernization programs with no margin for delay. For instance, although the Columbia–class SSBN currently remains on schedule, the transition from the Ohio to the Columbia is so fragile that, according to Admiral Johnny Wolfe, “[d]elays to the Navy’s SSBN modernization plan are not an option.”97 In an effort to keep the program on track, the shipbuilder reassigned workers from the Virginia–class attack submarine to the Columbia–class program, causing delays in the former.98

The effects of failing to replace current systems before their planned retirement dates are significant. As systems like the Minuteman III, ALCM, and Ohio–class submarines continue to age, efforts to sustain their required levels of performance become increasingly difficult and expensive. Age degrades reliability by increasing the potential for systems to break down or fail to perform correctly. Defects can have serious implications for U.S. deterrence and assurance. Should Sentinel fail to reach initial operating capability by 2029, the United States will be left with a less capable ICBM fleet, which will also begin to dip below 400 missiles as the Air Force continues to use missiles for annual testing. With respect to the Navy, the GAO has reported that if the first Columbia–class submarine is not delivered on time, “the Navy will have insufficient submarines available to meet the additional USSTRATCOM force-generation operational requirement of a total of 10 submarines,”99 which means less presence at sea.

Grade: U.S. nuclear platforms are in dire need of recapitalization. Plans for modernization of the nuclear triad are in place, and Congress and the services have largely sustained funding for these programs. The Sentinel ICBM remains on track for a flight test in 2023.100 In July 2021, the Air Force awarded Raytheon an engineering and manufacturing development contract for the LRSO, which also appears to remain on schedule.101 However, the fragility of these programs keeps them at risk of technical or funding delays, including appropriations through continuing resolutions.

The rapid modernization and expansion of nuclear forces underway in Russia and China clearly signal that U.S. efforts should receive similar attention and be undertaken with a commensurate sense of urgency. Growth in adversary forces has a direct impact on the required size of U.S. forces, including nuclear forces. The United States should consider procuring more of these modern systems than originally planned.

The United States will also need to consider acquiring additional capabilities to ensure that deterrence is tailored to the evolving Russian threat and the new Chinese threat. The SLCM-N, if it continues to receive funding from Congress, would begin to meet this challenge by providing the President with an option to respond more proportionally to—and therefore help deter—an adversary’s limited employment of nuclear weapons in a theater of conflict.

For now, replacing current systems remains the top priority, and while the commitment to nuclear weapons modernization demonstrated by Congress and the Administration is commendable, this category is trending toward “marginal” because of threat developments and delays (or the strong potential for delays) in U.S. modernization programs.

Nuclear Weapons Complex Score: Marginal

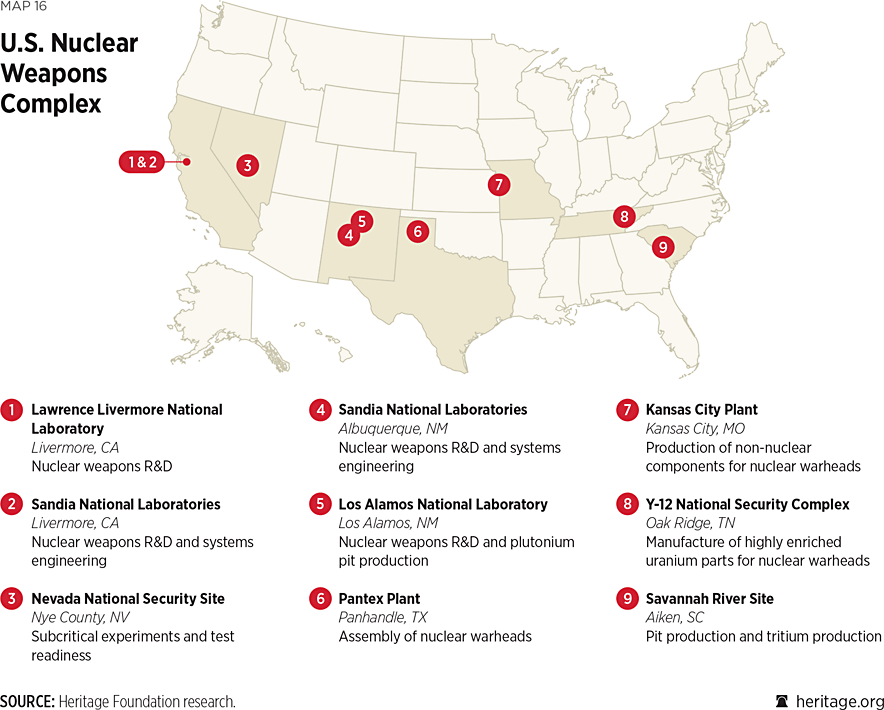

Maintaining a reliable and effective nuclear stockpile depends in large part on the facilities where U.S. devices and components are developed, tested, and produced. These facilities constitute the foundation of our strategic arsenal and include:

- The Los Alamos National Laboratories (nuclear weapons research and development, or R&D, and plutonium pit production);

- The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories (nuclear weapons R&D);

- The Sandia National Laboratory (nuclear weapons R&D and systems engineering);

- The Nevada National Security Site (subcritical experiments, test readiness);

- The Pantex Plant (assembly of nuclear warheads);

- The Kansas City Plant (production of non-nuclear components for nuclear warheads);

- The Savannah River Site (second site for pit production and tritium production); and

- The Y-12 National Security Complex (manufacture of highly enriched uranium parts for nuclear warheads).

These complexes design, develop, test, and produce the weapons in the U.S. nuclear arsenal, and their maintenance is therefore of critical importance. In the words of NNSA Administrator Jill Hruby, “A well-organized, well-maintained, and modern infrastructure system is the bedrock of a flexible and resilient nuclear security enterprise.”102 It contributes to deterrence by enabling the United States to adapt its nuclear arsenal to shifting requirements, signaling to adversaries that the United States can adjust its warhead capacity or capabilities when needed. Maintaining a safe, secure, effective, and reliable nuclear stockpile requires modern facilities, technical expertise, and tools both to repair any malfunctions quickly, safely, and securely and to produce new nuclear weapons when they are needed.

The existing nuclear weapons complex, however, is not capable of producing some of the nuclear components needed to maintain and modernize the stockpile on timelines that would be required for flexibility and resilience.103 Significantly, the United States has not had a substantial plutonium pit production capability since 1993. The U.S. currently retains more than 5,000 old plutonium pits in strategic reserve in addition to pits for use in future LEPs, but uncertainties regarding the effect of aging on plutonium pits and how long the United States will be able to depend on them before replacement remain unresolved. In 2006, a JASON Group study of NNSA assessments of plutonium aging estimated that, depending on pit type, the minimum pit life was in the range of 100 years.104 A work program was recommended to address additional uncertainties in pit aging but did not reach fruition. In addition to the pits needed for warheads like the W87-1 and W93, numerous pits have been in the stockpile for decades—some for more than 50 years—and will need to be replaced.

Today, the production rate is too low to meet the need to replace aging pits. The United States manufactured 10 W87-1 development pits in 2022.105 Statutory law requires the United States to produce no fewer than 80 pits per year (ppy) by 2030. In April 2021, the NNSA reached the first critical milestone for pit production at the Los Alamos National Laboratory.106 A second plutonium pit production facility is being planned to exploit the now-cancelled Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX) facility that was being constructed at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. Savannah River has a required production of no fewer than 50 ppy by 2030. It is already clear that the NNSA will not be able to meet the required deadline; rather, the organization states that it “remains firmly committed to achieving 80 ppy as close to 2030 as possible.”107

The GAO recently found that the “NNSA has not developed either a comprehensive schedule or a cost estimate” for the nation’s plan to reestablish plutonium pit production.108 These tools would improve the management of an already delayed program.109

Aside from plutonium, the NNSA must maintain production of several other key materials and components that are used to build and maintain nuclear weapons. For instance, it plans to increase the supply of tritium as demand increases. Because tritium is always decaying at a half-life of 12 years, delays in tritium production only increase the need to produce a timely replacement.110 The site preparations for the Tritium Finishing Facility began in FY 2023.111 Other projects currently underway include a new lithium processing facility and the new Uranium Processing Facility at Y-12.

Added to these considerations is the fact that 58 percent of the NNSA’s 5,000 facilities are more than 40 years old, and more than half are in poor condition.112 As a consequence, the NNSA had accumulated about $6.1 billion in deferred maintenance as of FY 2021.113

The NNSA has described high deferred maintenance as “a sign that infrastructure is in poor condition and in need of modernization” because of a lack of “significant, sustained, and timely funding.”114 Aging facilities also have become a safety hazard: In some buildings, for example, chunks of concrete have fallen from the ceiling.115 Moreover, without modern and functioning NNSA facilities, the U.S. will gradually lose the ability to conduct the high-quality experiments that are needed to ensure the reliability of the stockpile without nuclear testing.

Finally, despite the self-imposed nuclear testing moratorium that the United States has had in place since 1992, a functioning nuclear weapons complex requires a low level of nuclear test readiness. “Test readiness” refers to a single test or a very short series of tests, not a sustained nuclear testing program, reestablishment of which would require significant additional resources.

Since 1993, the NNSA has been mandated to maintain a capability to conduct a nuclear test within 24 to 36 months of a presidential decision to do so.116 Whether this approach can assure that the United States has the timely ability to conduct instrumented yield-producing experiments to correct a flaw in one or more types of its nuclear warheads is open to question. The United States might need to test to assure certain warhead characteristics that only nuclear testing can validate, or it might desire to conduct a nuclear weapon test for policy reasons.

However, the NNSA has been unable to achieve even this goal. According to the FY 2018 SSMP, it would take 60 months to conduct “a test to develop a new capability.”117 And according to the FY 2022 SSMP, “Assuring full compliance with domestic regulations, agreements, and laws related to worker and public safety and the environment, as well as international treaties would significantly extend the time required for execution of a nuclear test.”118 Because the United States is rapidly losing its remaining real-life nuclear testing experience, including instrumentation of very sensitive equipment, the process would likely have to be reinvented.119

Test readiness has not been funded as a separate program since FY 2010 and is instead supported by the Stockpile Stewardship Program that exercises testing elements at the Nevada National Security Site and conducts zero-yield nuclear laboratory experiments.120

Grade: Modernizing U.S. nuclear facilities is of critical importance because the NNSA’s warhead modernization plans depend on the ability to produce certain components like plutonium pits. The importance of a functioning nuclear weapons complex also has increased as the threat posed by adversaries has worsened. Given the change to a three-party nuclear peer dynamic and both Russia’s and China’s active nuclear production capabilities, the United States must maintain the ability to adapt its nuclear posture and hedge against an uncertain future.

The United States maintains some of the world’s most advanced nuclear facilities. Significant progress has been made over the past decade in getting funded plans in place to recapitalize plutonium pit production capacity and uranium component manufacturing in particular as well as construction projects for new facilities. Nevertheless, these programs face challenges and delays.

Some parts of the complex have not been modernized since the 1950s, and plans for long-term infrastructure recapitalization remain essential, especially as the NNSA embarks on an aggressive warhead life-extension effort. The weak state of U.S. test readiness is also of great concern. In a dynamic threat environment combined with an aging nuclear arsenal, the lack of this capability becomes more worrisome even as the NNSA improves its stockpile stewardship capabilities. Efforts to restore critical functions of the complex like pit production face great technical challenges and need stable funding. The recent shift in deadline for plutonium pit production at the Savannah River Site from 2030 to “as close to 2030 as possible” is one example. After years of deferred modernization, any unexpected failure or disruption at a critical facility could significantly affect schedules for nuclear warhead modernization.121

Until demonstrable progress has been made toward completion of infrastructure modernization, the grade for this category will therefore remain at “marginal.”

Personnel Challenges Within the National Nuclear Laboratories Score: Marginal

U.S. nuclear weapons scientists and engineers are critical to the health of the complex and the stockpile. According to the FY 2023 SSMP, the National Nuclear Security Administration’s “greatest asset” is its “highly qualified and skilled world-class scientific and engineering workforce, without which DOE/NNSA could not meet its vital national security missions.”122

The ability to maintain and attract a high-quality workforce is critical to ensuring the future of the American nuclear deterrent, especially when a strong employment atmosphere adds to the challenge of hiring the best and brightest. Today’s weapons designers and engineers are first-rate, but they also are aging and retiring, and their knowledge must be passed on to the next generation of experts. This is a challenge because “[r]oughly a quarter of the current enterprise workforce is eligible to retire, and there will likely remain a significant retirement-eligible population for the near future.”123

The NNSA also needs to retain talent among “early-career employees (age 35 and under)” and those with five or fewer years of experience.124 Young designers need meaningful and challenging warhead design and development tasks to hone their skills and remain engaged. The NNSA and its weapons labs understand this problem and, with the support of Congress, are beginning to take the necessary steps to invest in the next generation.

The judgment of experienced nuclear scientists and engineers is critical to assessing the safety, security, effectiveness, and reliability of the U.S. nuclear deterrent. Without their experience, the nuclear weapons complex could not function. Few of today’s remaining scientists or engineers at the NNSA weapons labs have had the experience of taking a warhead from initial concept to “clean sheet” design, engineering development, production, and fielding. The SRP is remedying some of these shortfalls by having its workforce exercise many of the nuclear weapon design and engineering skills that are needed. To continue this progress, SRP funding should be maintained if not increased.

According to the SSMP, “[n]early half of the total [NNSA] workforce have 5 years of service or fewer.”125 Given the length of time required to train new hires, the long timelines of warhead production cycles, and the time it takes to transfer technical knowledge and skills, both recruiting and retaining needed talent remain challenging for the NNSA.126

Grade: In addition to employing world-class experts, the NNSA labs have had good success in attracting and retaining talent (for example, through improved college graduate recruitment efforts and NNSA Academic Programs).127 As many scientists and engineers with practical nuclear weapon design and testing experience retire, continued annual assessments and certifications of nuclear warheads will rely increasingly on the judgments of people who have never participated in yield-producing experiments on their weapon designs. Moreover:

As NNSA mission scope increases, so does the demand for increased personnel to support new facilities and capabilities being brought on-line, and to support moving to 24/7 operations at many sites across the complex. These individuals are essential to minimizing unplanned outages and to supporting safe and secure operations, particularly in high hazard operations.128

Hazardous NNSA infrastructure and facilities can also be a hindrance to recruitment and retainment, so modernizing the nuclear weapons complex will be essential.129 Admiral Richard has emphasized the importance of investing in the workforce now: “If we lose those talent bases, you can’t buy it back. It will take 5 to 10 years to either retrain and redevelop the people or rebuild the infrastructure.”130

In light of these issues, the NNSA workforce earns a score of “marginal.”

Allied Assurance Score: Strong but Trending Toward Marginal

The credibility of U.S. nuclear deterrence is one of the most important components of allied assurance. The United States extends nuclear assurances to more than 30 allies that have forgone nuclear weapon programs of their own. If allies were to resort to building their own nuclear weapons because their confidence in U.S. extended deterrence had been degraded, the consequences for nonproliferation and stability could become dire.

Unfortunately, there are indications that such weakening is already taking place.131 According to a recent poll, for example, “more than 70% of South Koreans would support developing their own nuclear weapons or the return of nuclear weapons to their country.”132 Japan is openly discussing the possibility of eventually developing its own nuclear weapons, a topic considered taboo in the relatively recent past.133

In Europe, France and the United Kingdom deploy their own nuclear weapons independently of the United States. The United States also deploys B-61 nuclear gravity bombs in Europe as a visible manifestation of its commitment to its NATO allies and retains dual-capable aircraft that can deliver those gravity bombs. The United States provides nuclear assurances to Japan, South Korea, and Australia, all of which face increasingly aggressive nuclear-armed regional adversaries.

Continued U.S. nuclear deterrence assurances must be perceived as credible by adversaries and allies alike. Both Japan and South Korea have the capability and basic know-how to build their own nuclear weapons quickly, and Australia has had nuclear ambitions in the past. A decision by allies to build their own nuclear weapons would be a major setback for U.S. nonproliferation policies and could increase regional instability.

Grade: Not unlike deterrence, assurance and extended deterrence are about allies’ and adversaries’ perceptions of the U.S. nuclear umbrella’s credibility rather than what the United States thinks is a credible extended deterrent.

A worsening security environment appears to be causing U.S. allies to be more cautious when it comes to relying solely on U.S. extended deterrence commitments, and public debates about developing their own nuclear weapons appear to be more common than in the past. China continues to advance its capability to hold the U.S. homeland at risk with its strategic forces and to execute nuclear operations in the region. China has hundreds of nuclear-capable missiles in the region, and the United States deploys none. Both South Korean and Japanese leaders have recently discussed with President Biden the need to ensure that extended deterrence remains strong in light of these threats.134

European members of NATO continue to express their commitment to and appreciation of NATO as a U.S.-led nuclear alliance even as they worry about the impact of Russia’s growing non-strategic nuclear capabilities and nuclear saber-rattling over Western military support to Ukraine.135 According to the 2022 NPR, allied assurance remains one of the primary goals of U.S. nuclear forces,136 but while official statements remain positive, unofficial sentiment could indicate concern about U.S. extended deterrence commitments.

The 2018 NPR had proposed and allies had expressed support for two supplements to existing capabilities—a low-yield SLBM warhead and a new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile—as important initiatives to strengthen allied assurance.137 The low-yield SLBM warhead, deployed in 2020, is an important component of America’s ability to deter regional aggression against its Asian and NATO allies and remains deployed under the current Administration. However, the Biden Administration has proposed canceling the SLCM-N, a capability that could be deployed directly to regional theaters of conflict to help assure our allies.138

The score for allied assurance remains “strong” but is trending toward “marginal” as the United States continues to implement a “business-as-usual” approach in the face of significant negative regional developments. The United States will need to make concerted efforts to strengthen its commitments to extended deterrence to reflect the change in threat, both through its capabilities and by communicating resolve, if this score is to remain unchanged in future editions of this Index.

Overall U.S. Nuclear Weapons Capability Score: Marginal

The scoring for U.S. nuclear weapons must be considered in the context of a threat environment that is significantly more dangerous than it was in previous years. Until recently, U.S. nuclear forces needed to address one nuclear peer rather than two. Given a U.S. failure to adapt rapidly enough to these developments and the Biden Administration’s decision to cancel or delay various programs that affect the nuclear portfolio, this year’s Index changes the grade for overall U.S. nuclear weapons capability to “marginal.”

U.S. nuclear forces face many risks that without the continued bipartisan commitment to a strong deterrent could warrant an eventual decline to an overall score of “weak” or “very weak.” The reliability of current U.S. delivery systems and warheads is at risk as they continue to age and threats continue to advance. The fragility of “just in time” replacement programs only exacerbates this risk. In fact, nearly all components of the nuclear enterprise are at a tipping point with respect to replacement or modernization and have no margin left for delays in schedule; delays that are appearing to occur despite the best efforts of the enterprise. Since every other military operation—and therefore overall national defense—relies on a strong nuclear deterrent, the United States cannot afford to fall short in fulfilling this imperative mission.

Future assessments will need to consider plans to adjust America’s nuclear forces to account for the doubling of peer nuclear threats. It is clear that the change in threat warrants a reexamination of U.S. force posture and the adequacy of our current modernization plans.

Therefore, the score for this portfolio was changed from “strong” to “marginal.” Failure to keep modernization programs on track while planning for a three-party nuclear peer dynamic could lead to a further decline in the strength of U.S. nuclear deterrence in future years.

Endnotes

[1] All of the past six confirmed Secretaries of Defense—including current Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin—have affirmed U.S. nuclear deterrence as the department’s number one mission.

[2] Admiral Charles A. Richard, Commander, United States Strategic Command, statement before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, April 20, 2021, p. 3, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Richard04.20.2021.pdf (accessed July 23, 2023).

[3] U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, p. 7, in 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America Including the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review and the 2022 Missile Defense Review, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF (accessed July 25, 2023).

[4] U.S. Department of Defense, 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, February 2018, p. VII, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF (accessed July 26, 2023).

[5] U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, p. 16.

[6] Keith B. Payne, “The 2022 NPR: Commendation and Concerns,” in Keith B. Payne, ed., Expert Commentary on the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, National Institute for Public Policy Occasional Paper, Vol. 3, No. 3 (March 2023), p. 93, https://nipp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/OP-Vol.-3-No.-3.pdf (accessed July 23, 2023).

[7] Bryant Harris, “Republicans Lay Battle Lines over Biden’s Plan to Retire B83 Megaton Bomb,” Defense News, May 19, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/congress/budget/2022/05/19/republicans-lay-battle-lines-over-bidens-plan-to-retire-b83-megaton-bomb/ (accessed July 23, 2023).

[8] Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “Why America Must Lead Again: Rescuing U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again (accessed July 23, 2023).

[9] U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, pp. 11–13.

[10] Gregory Weaver, statement on “Regional Nuclear Deterrence” before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 28, 2023, p. 3, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Mr.%20Gregory%20Weaver%20Written%20Statement%20-%20Regional%20Nuclear%20Deterrence%20-%2003.28%20SASC%20FINAL.pdf (accessed July 23, 2023). Emphasis in original.

[11] Choe Sang-Hun, “In a First, South Korea Declares Nuclear Weapons a Policy Option,” The New York Times, January 12, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/world/asia/south-korea-nuclear-weapons.html (accessed July 23, 2023).

[12] Admiral Charles A. Richard, Commander, United States Strategic Command, statement before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 8, 2022, p. 3, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2022%20USSTRATCOM%20Posture%20Statement%20-%20SASC%20Hrg%20FINAL.pdf (accessed July 23, 2023).