U.S. Navy

Brent D. Sadler

Navies exist to assure access to markets and influence events on land for political ends and to prevail in maritime combat when war occurs. To these ends, the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard (known collectively as the sea services) have enabled America to project power across the oceans, controlling activities on the seas whenever and wherever needed.

According to the Department of the Navy’s annual budget briefing for fiscal year (FY) 2024, the service’s three “enduring priorities” as articulated by the Secretary of the Navy are:

- “Strengthening Maritime Dominance in Order to Defend the Nation,”

- “Taking Care of People through Building a Culture of Warfighting Excellence,” and

- “Succeeding through Teamwork by Enhancing Strategic Partnerships.”1

President Joseph Biden’s proposed $202.5 billion Navy budget for FY 2024 represents a $9.7 billion increase over the FY 2023 enacted budget—an increase of 5 percent.2 While this increase is needed, it is not enough to deliver on the Secretary’s goals given persistent inflationary pressures and the rapidly modernizing and expanding Chinese threat.

The Navy remains under immense strain to maintain readiness for combat while also conducting the daily peacetime operations that are necessary to compete with the activities of China and Russia. In the year since publication of the 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength, there have been several significant developments that are important to the Navy. For example:

- In January 2023, the Navy shut down its dry docks at the west coast Puget Sound public shipyard and Bremerton naval base to assess vulnerability to earthquake damage.3 This affected the submarine Connecticut, which was awaiting repairs following a collision with an uncharted seamount on October 2, 2021, in the South China Sea, sustaining significant damage.4

- On January 10, 2023, the Navy discontinued tracking and reporting on COVID deaths and vaccinations. The final numbers as of February 10, 2023, are 17 uniformed member deaths due to COVID and 1,878 sailors separated for refusing the vaccine.5

- On March 13, 2023, after an 18-month review, President Biden was joined in San Diego by prime ministers from the United Kingdom (U.K.) and Australia to announce the way ahead for the Australia–U.K.–U.S. (AUKUS) partnership to develop an Australian nuclear submarine program.6 This plan includes a rotational presence of U.S. nuclear submarines to be based out of Australia in this decade, ostensibly to train Australian sailors and maintainers in naval nuclear routines as well as to improve forward naval presence.

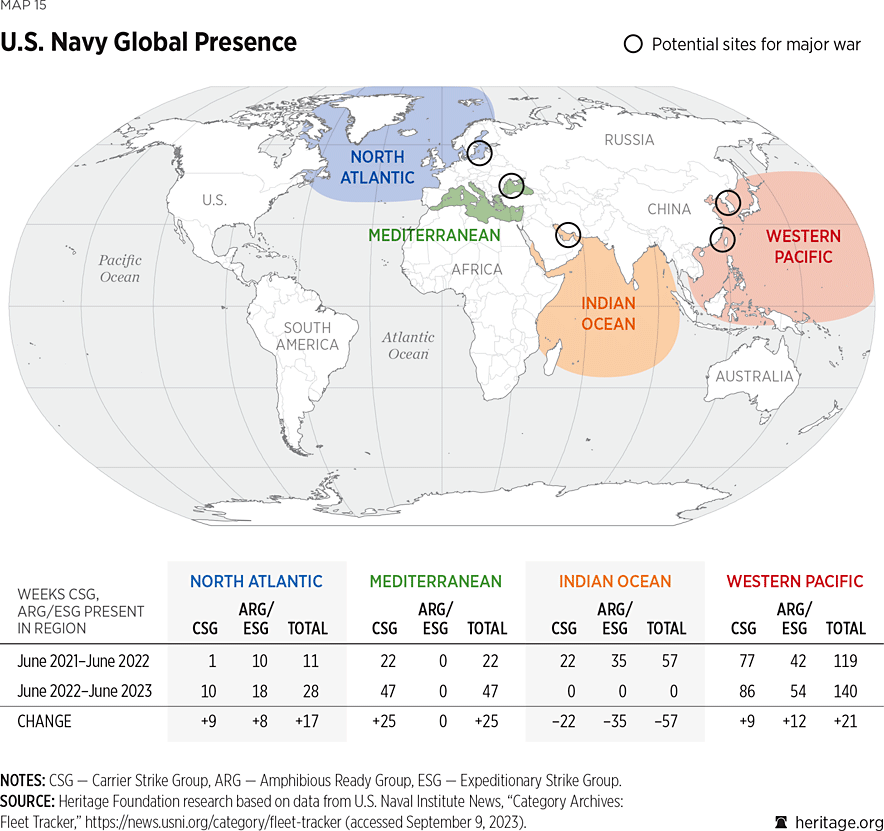

- On April 4, 2023, the Secretary of the Navy announced that the Fourth Fleet will establish an unmanned task force modeled on the successful Fifth Fleet Task Force 59.7

Strategic Framework. In December 2020, to address today’s maritime competition more effectively, the sea services released a naval strategy titled Advantage at Sea.8 It has not yet been fully executed, but there has been some progress regarding forward presence operations that challenge Chinese maritime coercion.9 To this end, the Navy apparently continues to adjust its deployment patterns to meet new demands caused by the war in Ukraine and increasing tensions in Asia: two carrier strike groups in the Western Pacific (with the exception of four months when only one was present) and a single carrier strike group in the Mediterranean since June 2022. This marks a slight reduction in carrier presence in the Western Pacific from December 2021.10

As the U.S. military’s primary maritime arm, the Navy is charged with providing the enduring forward global presence that this strategy requires while retaining war-winning forces. The Navy therefore continues to focus its investments on several functional areas: power projection, control of the seas, maritime security, strategic deterrence, and domain access. This approach is informed by several key documents:

- The October 2022 National Security Strategic Guidance;11

- The December 2020 Advantage at Sea naval strategy;

- The 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS) (only an unclassified fact sheet has been released to the public);12 and

- The Global Force Management Allocation Plan (GFMAP).13

U.S. official strategic guidance requires the Navy to act beyond the demands of conventional warfighting. China and Russia use their fleets to establish a physical presence in regions that are important to their economic and security interests in order to influence the policies of other countries. To counter their influence, the U.S. Navy similarly sails ships in these waters to reassure allies of U.S. commitments and signal to competitors that they do not have a free hand to impose their will. This means that the Navy must balance two key missions: ensuring that it has a fleet that is ready for war while also using that fleet for peacetime “presence” operations. Both missions require crews and ships that are materially ready for action and a fleet that is large enough to maintain presence and marshal enough combat power to win in battle.

On July 26, 2022, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) released a new Navigation Plan 2022 (NAVPLAN 2022) to provide guidance for the Navy’s contribution to the execution of the National Defense Strategy. In this latest edition, the CNO continues his emphasis on forward presence in the United States’ daily competition with rivals like China and prioritizes investments in key capabilities like defense against anti-ship missiles and other forms of attack, logistical support capabilities that remain viable in combat, and the ability to share information even when the enemy is targeting the Navy’s ability to do so. NAVPLAN 2022 also emphasizes weapons with increased range, new deception capabilities, and improved abilities to make time-critical decisions.14

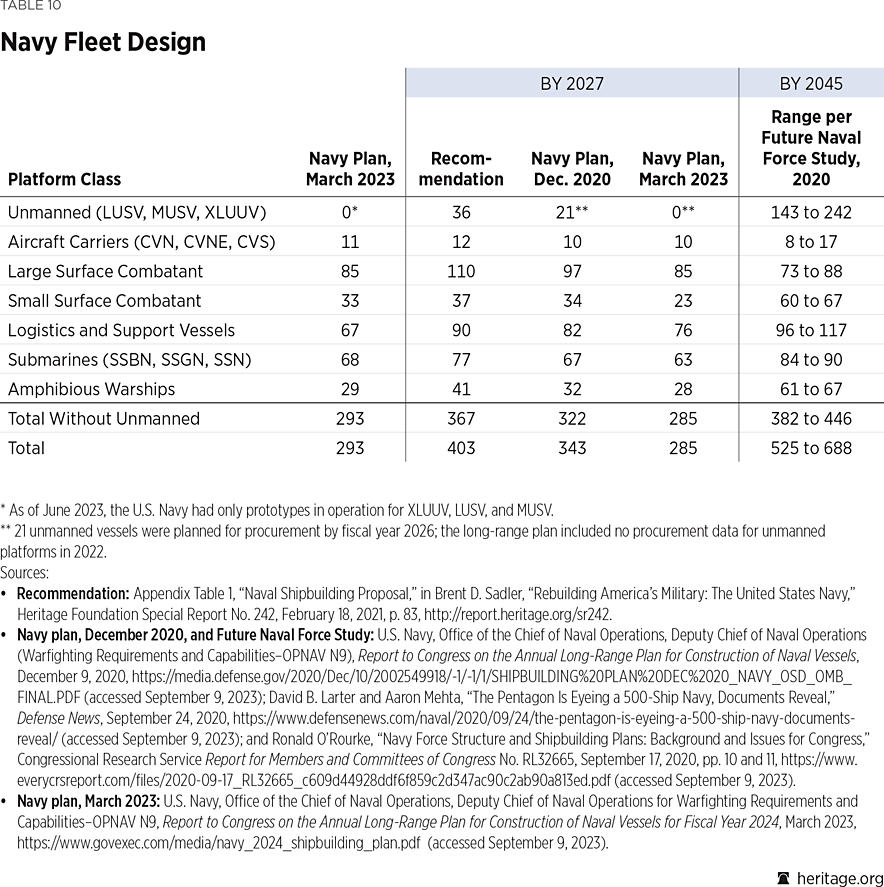

All of this reflects a continuation of demands stemming from the Distributed Maritime Operations concept that has been deemed critical to defeating Chinese anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. However, NAVPLAN 2022 lacks a clear timeline either for delivering these capabilities or for ensuring that the fleet is able to employ them in what the CNO acknowledges is a dangerous decade. NAVPLAN 2022 also has added to the several fleet-sizing plans offered by the Navy in recent years, calling for a fleet of 350 manned and 150 unmanned warships along with 3,000 naval aircraft—but without clearly explaining how it will achieve results in a way that the other plans could not.

Lacking a clear operational focus and resourcing strategy, NAVPLAN 2022 has not galvanized political support and has failed to deliver marked improvement either in fleet capabilities or in capacities to deter an increasingly aggressive China. In fact, the most recent long-range shipbuilding plan provides Congress only with a way ahead for a smaller naval force by the end of the decade.15 Such a disconnect between strategy, plans, and resourcing persists with the latest Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirement, which indicates that the Navy is short 80 warships (rather than 50) to execute the National Defense Strategy.16

This Index focuses on the following elements as the primary criteria by which to measure U.S. naval strength:

- Sufficient capacity to defeat enemies in major combat operations and provide a credible peacetime forward presence to maintain freedom of shipping lanes and deter aggression,

- Sufficient technical capability to ensure that the Navy is able to defeat potential adversaries, and

- Sufficient readiness to ensure that the fleet can “fight tonight” given proper material maintenance, personnel training, and physical well-being.

Capacity

Force Structure. The Navy is unique relative to the other services in that its capacity requirements must meet two separate objectives:

- During peacetime, the Navy must maintain a global presence in distant regions both to deter potential aggressors and to assure allies and security partners.

- The Navy must be able to win wars. To this end, the Navy measures capacity by the size of its battle force, which is composed of ships it considers directly connected to combat missions.17

This Index continues the benchmark set in the 2019 Index: 400 ships to ensure the capability to fight two major regional contingencies (MRCs) simultaneously or nearly simultaneously, as well as a 20 percent strategic reserve, and historical levels of 100 ships that are forward deployed in peacetime.18 This 400-ship fleet is centered on providing:

- 13 Carrier Strike Groups (CSGs);

- 13 carrier air wings with a minimum of 624 strike fighter aircraft;19 and

- 15 Expeditionary Strike Groups (ESGs).20

Unmanned platforms are not included because they have not matured as a practical asset. They hold great potential and will likely be a significant capability, but until they are developed and fielded in larger numbers, their impact on the Navy’s warfighting potential remains speculative. The same holds true across the fleet when it comes to new classes of ships. The Navy is investing in research, modeling, war gaming, and intellectual exercises to improve its understanding of the potential utility of new ship and fleet designs, but until new ships are added to the fleet, it is hard to know how they will affect the Navy’s ability to perform its missions. Consequently, this Index measures what is known and can be known in naval affairs, assessing the current Navy’s size, modernity, and readiness to perform its most important missions today.

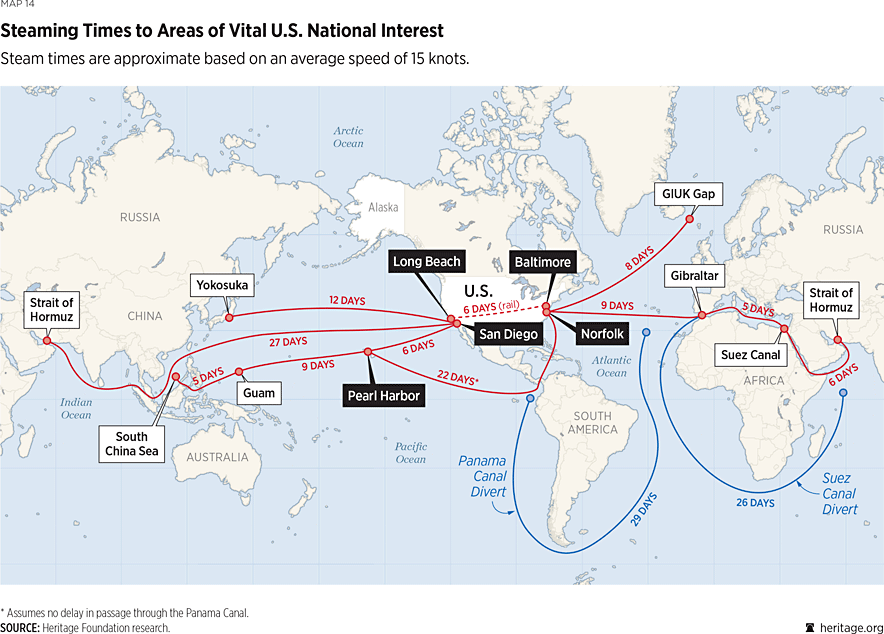

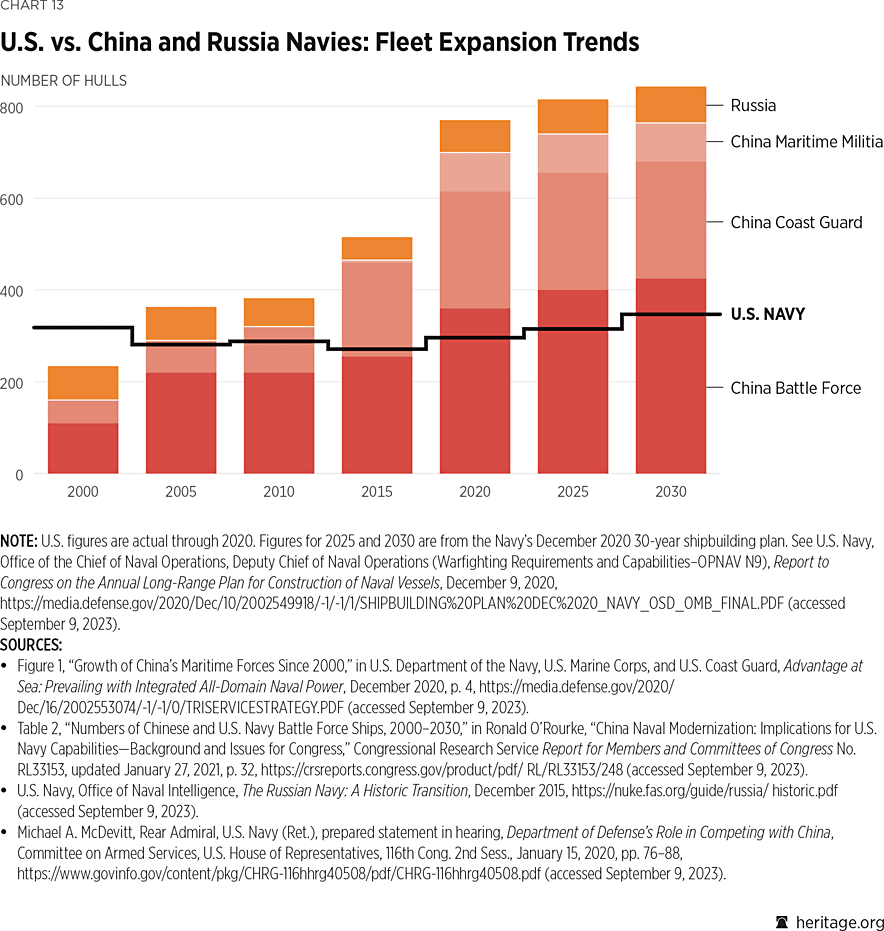

Relative to the above metric, the Navy’s fleet of 297 warships as of August 31, 2023—one ship less than a year ago—is inadequate and places greater strain on the ability of ships and crews to meet existing operational requirements. To alleviate the operational stress on an undersized fleet, the Navy has attempted since 2016 to build a larger fleet. However, for myriad reasons, it has been unable to achieve sustained growth and in fact has underdelivered by approximately 10 ships each year since 2016.21 In the past, the Navy has had some success in meeting operational requirements with fewer ships by posturing ships forward as it has done in Rota, Spain; on Guam; and potentially as part of AUKUS in Australia.

At a February 2022 naval conference, the Chief of Naval Operations stated, “I’ve concluded—consistent with the analysis—that we need a naval force of over 500 ships.”22 He went on to specify that this fleet would include 12 carriers, 19 to 20 large amphibious warships, more than 30 smaller amphibious ships, 60 destroyers, 50 frigates, 70 attack submarines, and a dozen ballistic missile submarines, all backed by 100 support ships and 150 unmanned vessels. Based on the CNO’s military advice and Heritage Foundation analysis, today’s fleet remains too small to meet today’s threats with maximum effectiveness.

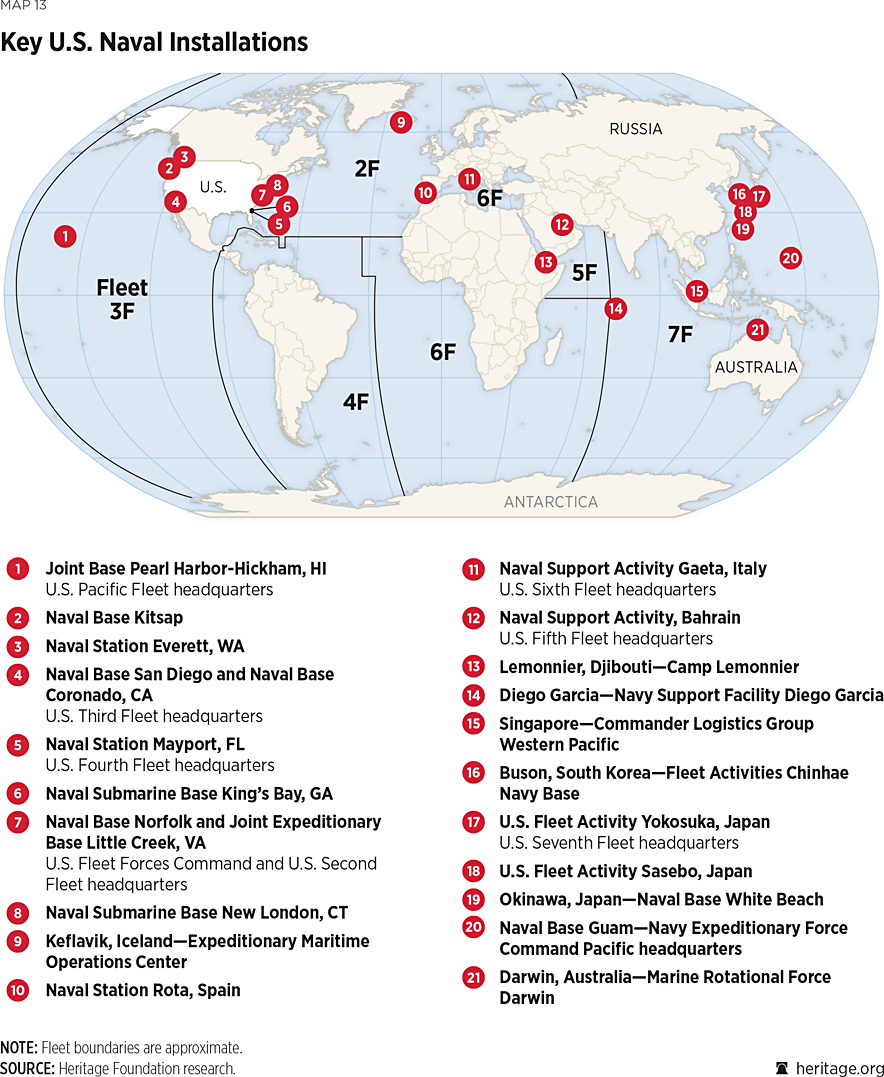

Posture/Presence. Although the Navy remains committed to sustaining forward presence, it has struggled to meet the requests of regional Combatant Commanders. The result has been longer and more frequent deployments to meet a historical steady-state forward presence of 100 warships.23 In 1985, at the height of the Cold War, the percentage of the 571-ship fleet deployed was less than 15 percent, and throughout the 1990s, deployments seldom exceeded the six-month norm: Only 4 percent to 7 percent of the fleet exceeded six-month deployments on an annual basis.24

Using the Navy’s aircraft carrier fleet—the most taxed platform—as a sample set, for 20 years, approximately 25 percent of the aircraft carrier fleet has been deployed. Following the 2017 deadly collisions involving USS McCain and USS Fitzgerald, the overall fleet deployment percentage dropped temporarily to less than 20 percent, but it surged again to almost 30 percent in 2020.25 High operational tempo (OPTEMPO) remains an issue as the Navy works to secure U.S. interests against increasing Chinese distant naval deployments and provocations, North Korea’s ballistic missile submarine, Iranian attacks on and interdiction of commercial shipping in the Persian Gulf, and an active Russian Navy.

The numbers as of August 31, 2023, are typical for a total battle force of 297 deployable ships with 74 warships at sea: 41 deployed and underway and 33 underway on local operations for an OPTEMPO of 24.9 percent, well above Cold War levels.26 Given Combatant Commanders’ requirements for naval presence, there is impetus to have as many ships forward deployed as possible by:

- Homeporting. The ships, crew, and their families are stationed at the port or based abroad (for example, a CSG in Yokosuka, Japan).

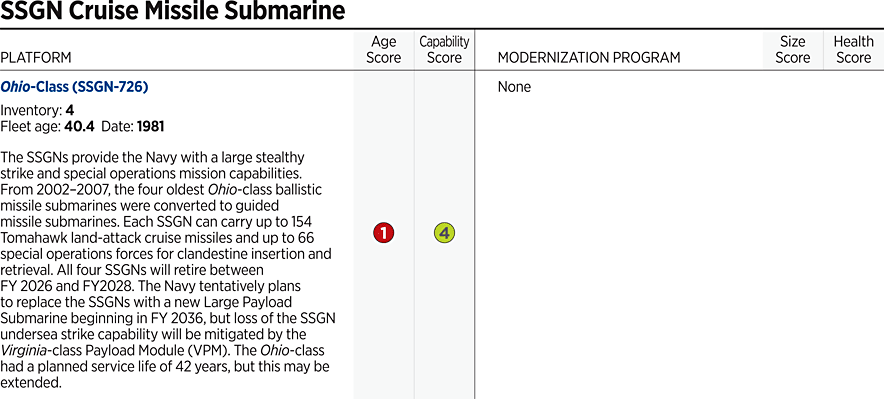

- Forward Stationing. Only the ships are based abroad, and crews are rotated out to the ship.27 This deployment model is currently used for Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) and Ohio–class guided missile submarines (SSGNs) manned with rotating blue and gold crews, effectively doubling the normal forward deployment time (for example, LCS in Singapore).

These options allow one forward-based ship to provide a greater level of presence than four ships based in the continental United States (CONUS) can provide by offsetting the time needed to transit ships to and familiarize their crews with distant theaters.28 This is captured in the Navy’s GFM planning assumptions: a forward-deployed presence rate of 19 percent for a CONUS-based ship compared to a 67 percent presence rate for an overseas-homeported ship.29 To date, the Navy’s use of homeporting and forward stationing has not mitigated the effect of the reduction in overall fleet size on forward presence.

Shipbuilding Capacity. To meet stated fleet-size goals, the Navy must build faster and maintain more ships, exceeding its current capacity. However, significant shortfalls in shipyards, both government and commercial, make it hard to accomplish either task, and underfunded defense budgets make it even more difficult. Given the limited ability to build ships, the Navy will struggle to meet the congressionally mandated 355-ship goal,30 to say nothing of the 400-ship goal advocated in this Index.

Since FY 2020 the Navy’s procurement of warships has averaged 12 per year, but only after Congress has added funding above the President’s proposed budget to support an average of three additional warships each year. Moreover, subsequent procurement has not kept pace with the threat from China and does not appear to meet congressional mandates. For example, Congress has mandated that the Navy should achieve a fleet of 12 aircraft carriers,31 but the number is shrinking to nine (possibly to be augmented by a light carrier that has yet to be defined).32

However, it was the Navy’s failure to propose a long-range build plan that met congressional mandates for 31 amphibious warships that boiled over in 2023.33 World events demonstrated the danger of having inadequate amphibious forces in April 2023 when Americans were stranded amid flaring factional war in Sudan. Marine Corps Commandant General David Berger made clear before the House Armed Services Committee that the lack of “a sea based option” contributed directly to complicating the evacuation of citizens out of harm’s way. Sea-based options are “how we reinforce embassies. That’s how we evacuate them. That’s how we deter.”34

Despite such consequences, the current long-range shipbuilding plan does not provide a plan to reverse downward trends in the fleet. Instead, in accordance with the President’s planned procurement over the next five years, the battle force inventory will drop to 280 manned ships by FY 2027.35

Meanwhile, diminished demand for ships has led shipbuilders to divest workforce and delay capital investments. From 2005 to 2020, the Navy’s procurement of new warships increased the size of the fleet from 291 to 296 warships; at the same time, China’s navy grew from 216 to 360 warships.36 If the Navy is to build a larger fleet, more shipbuilders will have to be hired and trained—a lengthy process that precedes any expansion of the fleet. Recent labor statistics comparing 2017 to 2021 show modest progress with total shipbuilding labor involved in production, like welders and pipefitters, adding 3,134 workers.37 On the other hand, according to the most recent labor statistics, wages in the nation’s shipbuilding sector have not kept pace with inflation, growing at 0.4 percent, and the sector has shed 2.6 percent of its already small cadre of professional naval architects and engineers.38

Of particular concern is the need to increase the production of nuclear-powered warships, most notably nuclear-powered submarines that would be vital in any conflict with China. Limited nuclear shipbuilding capacity39 may constrain the Navy’s plans to increase the build rate from two attack submarines per year to three while concurrently building one ballistic missile submarine.40 To support a larger nuclear-powered fleet, the relevant public shipyards increased their workforce by 16 percent from 2013 to 2020,41 but recent developments indicate that required workforce growth has not continued. The Virginia–class attack submarine program is 25 percent below staffing needs with delays of up to two years in delivery of the latest Block V variant, which will deploy large numbers of cruise missiles and potentially hypersonic strike weapons.42 As demand for nuclear-powered warships increases, to include added demand to support AUKUS, to pace the threat from China and Russia into the foreseeable future, the public shipyards must be able to sustain the recruitment of skilled labor in the numbers needed.

It remains true, according to the Chief of Naval Operations, that current funding will not build or maintain the larger fleet that both the Navy and this Index say is needed and that Congress has mandated. Nothing has changed to alter CNO Admiral Michael Gilday’s 2021 assessment that current budgets can only “sustain a Navy of about 300 to 305 ships.”43 In addition, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has noted that a brittle defense industrial base continues to drive up costs and create delays.44

Manpower. In 2018, the Navy assessed that its manpower would need to grow by approximately 35,000 to achieve an end strength of 360,395 sailors to support a 355-ship Navy.45 For comparison, the last time the Navy had a similar number of ships was in 1997, when it had 359 ships and a total of 398,847 personnel.46 As of May 19, 2023, the Navy consisted of 335,187 officers and sailors,47 down 9,640 from the 344,824 reported as of June 2022,48 leading to a growing deficit of 25,208 below what is needed to meet its 2034 fleet goal.

Regrettably, trends for the Navy’s personnel budget and for its recruiting and retention efforts are pointing in the wrong direction. Despite the need for more sailors and officers, total end strength has fallen from 344,441 in FY 2022 to an estimated 341,736 in FY 2023 and is trending toward 342,700 in FY 2028.49 If approved, the most recent budget request would bend this downward curve by raising FY 2024 manning to 347,000,50 but this is not necessarily a cure for the Navy’s recruiting woes. Authorized manning numbers should reflect the fleet needed rather than what can be recruited today, and it remains to be seen whether retention rates can be sustained to meet long-range manning needs. According to data provided by the Navy’s Personnel Command, while officer retention has remained relatively flat in recent years, enlisted retention has declined consistently between FY 2018 and FY 2022.

Failing to meet retention goals while at the same time falling short of recruitment goals will place greater demand on a smaller active-duty end strength, and the consequences will be seen in the operational capabilities of the Navy’s fleet. The GAO has reported persistent crew manning shortfalls. A GAO report published in May 2021 showed some ships with crew shortfalls as high as 15 percent, which compounded crew fatigue as smaller crews had to make up the workload. This was a contributing factor in fatal collisions in 2017.51

Finally, the effort to attract people to join the Navy is made more difficult by wages that are not keeping up with inflated costs of living. In the battle for people, pay raises in recent years have consistently lagged behind inflation, the latest proposed 5.2 percent raise being the first in several years to be slightly ahead of inflation, which stood at 4.9 percent between April 2022 and April 2023.52

Capability

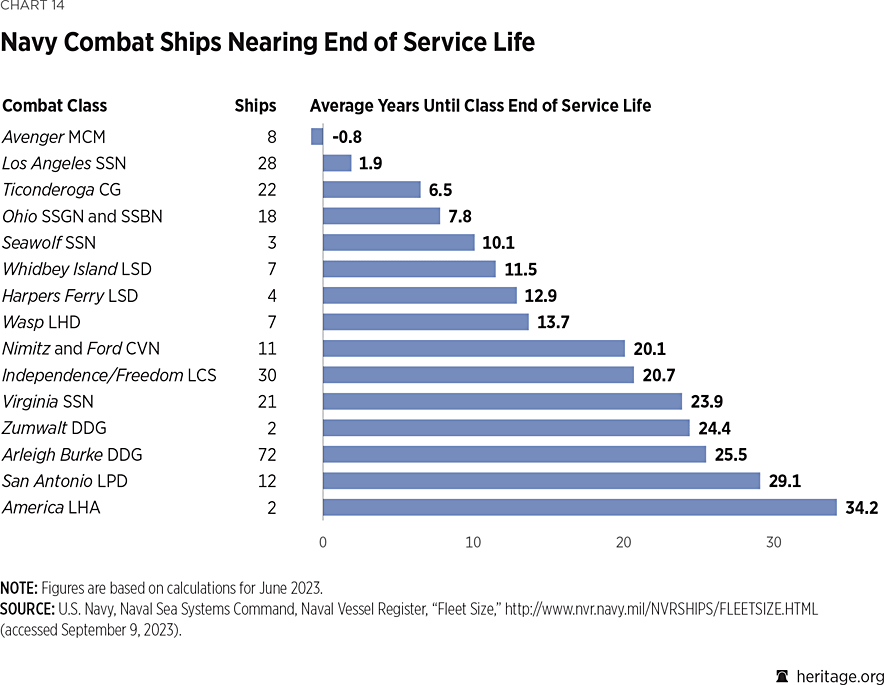

A complete measure of naval capabilities requires an assessment of U.S. platforms against enemy weapons in plausible scenarios. The Navy routinely conducts war games, exercises, and simulations to assess this, but insight into its assessments is limited by their classified nature. This Index therefore assesses capability based on remaining hull life, mission effectiveness, payloads, and the feasibility of maintaining the platform’s technological edge.

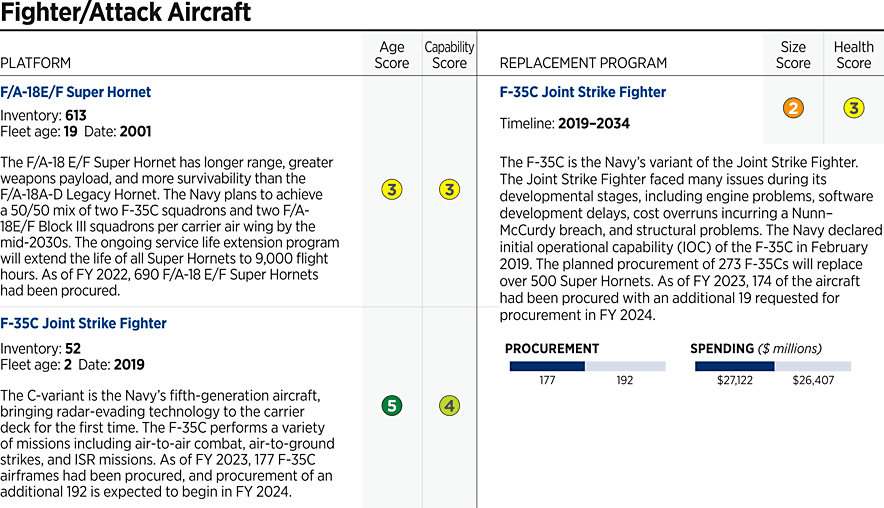

Most of the Navy’s fleet consists of older platforms: Of the Navy’s 20 classes of ships, only eight are in production. However, because Congress added almost $15 billion to the FY 2023 budget, the proposed $255.8 billion Department of the Navy budget for FY 2024 represents a real dollar increase of $11.0 billion, which is a relative increase of 4.5 percent from the previous year, and procurement is set to increase by two points to 6 percent of the Navy’s budget.53 The following are highlights by platform.

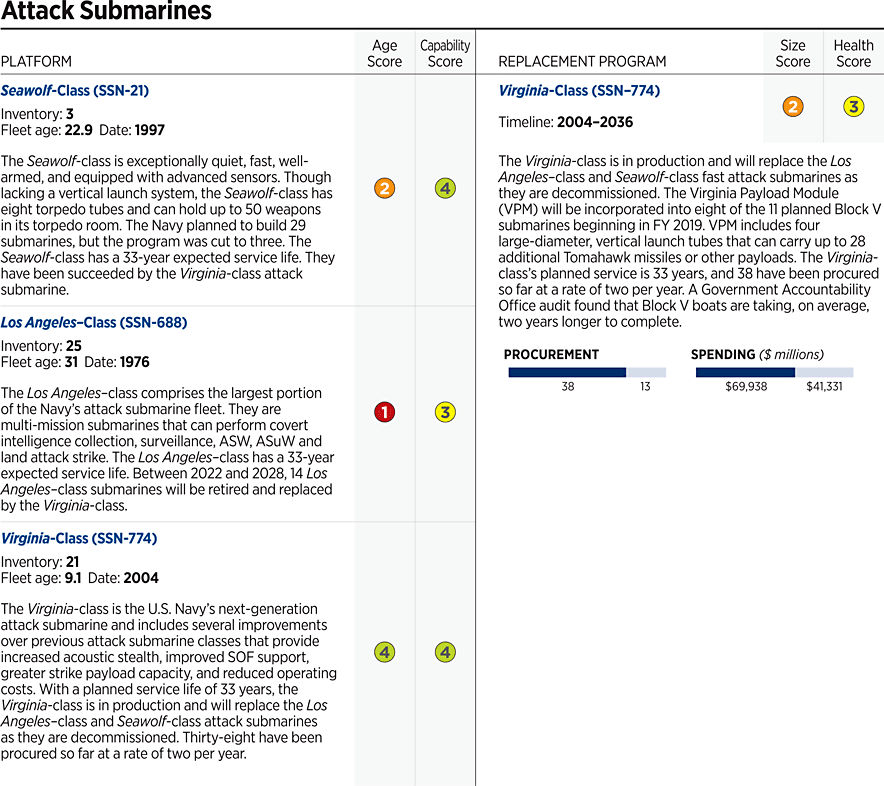

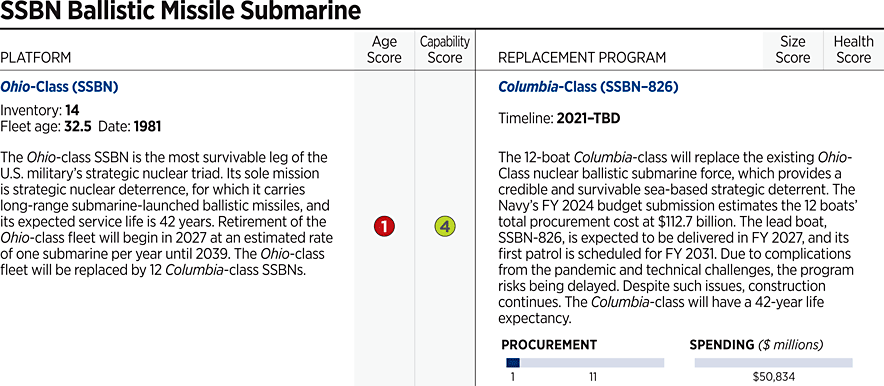

Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBN). The Columbia–class submarine will relieve the aging Ohio–class SSBN fleet. Because of the implications of this change for the nation’s strategic nuclear deterrence, the Columbia–class SSBN remains the Navy’s top acquisition priority. To ensure the continuity of this leg of the U.S. nuclear triad, the first Columbia–class SSBN must be delivered on time for its first deterrent patrol in 2031.54 In November 2020, the Navy signed a $9.47 billion contract with General Dynamics Electric Boat for the first-in-class boat and advanced procurement for long-lead-time components of the second hull.55 The lead ship’s keel-laying ceremony occurred on June 4, 2022.56

However, concerns persist in Congress that the Department of Defense (DOD) may not be fully utilizing special authorities granted to the Navy to ensure that this critical program is adequately resourced. Specifically, in 2014, Congress established the National Sea-Based Deterrence Fund (NSBDF), which has saved more than $1.4 billion using flexible funding, but it “has yet to utilize the core function of the NSBDF—namely, to provide increased flexibility to repurpose funds into it to buy down the fiscal impact of the program on our other shipbuilding priorities.”57

Nuclear Attack Submarines (SSN). SSNs are multi-mission platforms whose stealth enables clandestine intelligence collection; surveillance; anti-submarine warfare (ASW); anti-surface warfare (ASuW); insertion and extraction of special operations forces; land attack strikes; and offensive mine warfare. The newest SSN class, the Block V Virginia with the Virginia Payload Module (VPM) enhancement, is important to the Navy’s overall strike capacity, enabling the employment of an additional 28 Tomahawk cruise missiles over earlier SSN variants.58 Construction of Block V submarines began in September 2019 with the Oklahoma (SSN 802) to be delivered in May 2027 and three more boats to be delivered before the end of the decade.59 As noted previously, a limited shipyard workforce is causing this program to be delayed by as many as two years.

The FY 2021 National Defense Authorization Act included additional funds for advanced procurement that preserves a future option to buy as many as 10 Virginia–class submarines through the end of the decade. The FY 2024 budget supports this with a sustained build rate of two Virginia–class submarines a year through FY 2028. As indicated previously, increasing Virginia–class production for AUKUS has raised concerns regarding strain on the industrial base, and the FY 2023 budget put $1.6 billion toward expansion of the submarine industrial base “to support the Navy plan of serial production of 1 COLUMBIA plus 2 VIRGINIAs starting in FY25/26.”60 Marks to the FY 2024 proposed defense budget point to continued congressional support for increased naval shipbuilding capacity.61

The effectiveness of such efforts, however, must be measured not by intent, but by results: delivery of warships on time. At the same time, supply-chain quality control is a key factor in submarine construction, and if it is not done well, the consequences can be catastrophic. That is why the premature replacement of critical submarine parts in 2021—parts that are intended to last the life of the boat—remains a concern.62 Added vigilance will be required as the Navy finds new suppliers to meet future increased submarine production as well as the potential need to provide support to AUKUS.

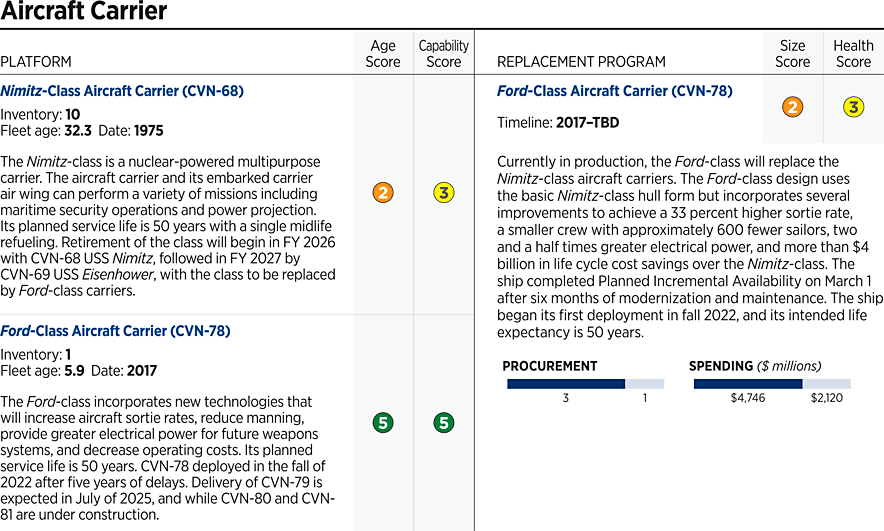

Aircraft Carriers (CVN). The Navy has 11 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers: 10 Nimitz–class and one Ford–class. The Navy has been making progress in overcoming nagging issues with several advanced systems, notably advanced weapons elevators, and the Ford’s first operational deployment in the fall of 2022 to the North Atlantic.63 Further bolstering confidence in this new class, the Ford deployed to the Mediterranean in May 2023 to sustain a persistent carrier presence there following Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.64 The second ship in the class, USS John F. Kennedy (CVN 79), was christened on December 7, 2019, but its scheduled delivery to the Indo-Pacific theater has slipped from 2022 to 2025 to support late modifications for fifth-generation fighters like the F-35.65 The Kennedy is to be followed by the Enterprise (CVN 80), which is in early construction with delivery planned for 2028.

The U.S. lead in this category of naval power may be waning as China completes construction of its first super carrier. As the U.S. Navy struggles to build, maintain, and crew a fleet of 11 aircraft carriers, China is rapidly catching up both in numbers and in platform capability. Its newest carrier, the Type-003, like the Ford–class, will utilize electromagnetic catapults that give its air wing greater range and sortie rates, thus greatly narrowing the capability gap.66 The Type-003 is China’s second indigenously built carrier, marking a significant engineering milestone. There had been renewed emphasis on having the ship delivered before the October 2022 Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress,67 and after a sprint by the shipyard, the new 80,000-ton Type-003 aircraft carrier was launched in June 2022.68 China’s growing naval aviation and aircraft carrier capabilities place added stress on U.S. naval aviation and air defenses.

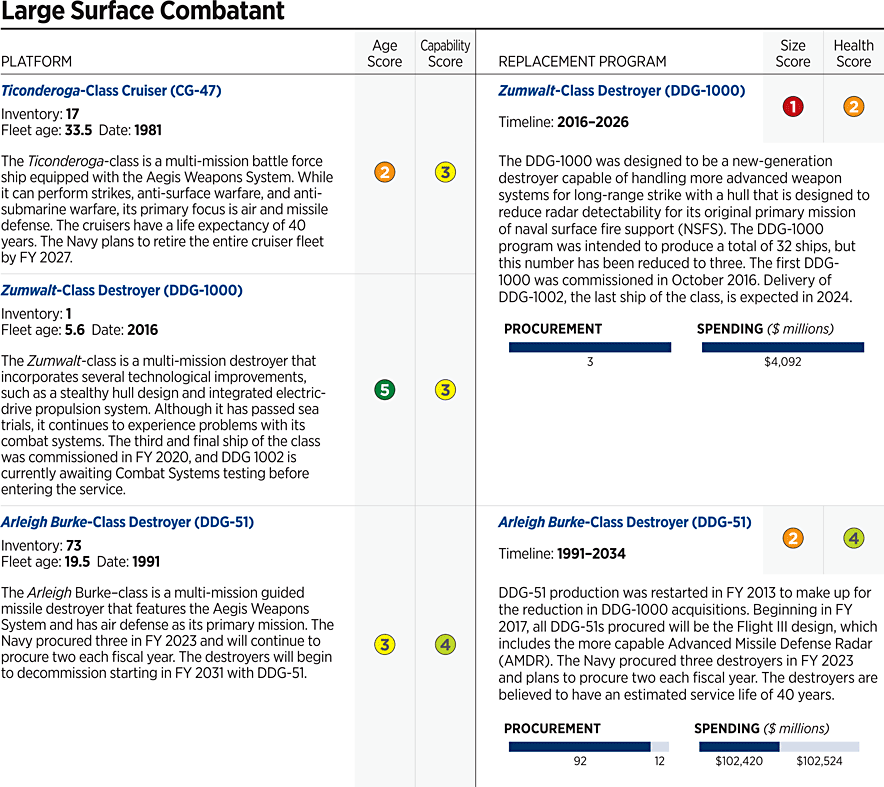

Large Surface Combatants. The Navy’s large surface combatants consist of the Ticonderoga–class cruiser, the Zumwalt–class destroyer, and the Arleigh Burke–class destroyer. The President’s FY 2024 budget would decommission five of the 13 aged Ticonderoga–class cruisers in the Navy’s FY 2023 inventory.69 Should Congress succeed in retaining two of these cruisers, decommissioning of the remaining three would still represent a significant decrement of the Navy’s sea-launched firepower with the loss of a total of 366 vertical launch tubes. Attempts to repurpose or extend the life of the aging Ticonderoga–class cruisers have yielded mixed results, as deferred upgrades and past incomplete maintenance are driving up operating costs.70

In FY 2022, the Navy procured two Arleigh Burke–class DDG 51 destroyers, bringing the total on active duty in the fleet to 70, and 14 more have been ordered. Since the Navy declined to pursue a new cruiser in 2008, it has relied on a final iteration of the Arleigh Burke class, Flight III, to provide air and missile defense for aircraft carrier strike groups.71 This will remain a stopgap measure until a more capable new destroyer, DDG(X), joins the fleet, probably in the next decade. The Navy’s other modern destroyer, the Zumwalt class, was never intended as a cruiser replacement and looks to fill a limited long-range strike role.

The Zumwalt class was envisioned as bringing advanced capabilities to the fleet, but the program has suffered technological problems and cost overruns, and the Navy has not indicated that it intends to acquire more than the three that have already been purchased and are being built out: the USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000), which was delivered on April 24, 2020; USS Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001), which was commissioned on January 26, 2019; and USS Lyndon B. Johnson (DDG-1002), which is completing checks before delivery to the Navy in 2024.72 The Zumwalt is currently based in San Diego, but its initial operational capability (IOC) has been delayed by a year, overlapping with plans to install the Navy’s new hypersonic weapons system, conventional prompt strike (CPS), beginning in October 2023 with the remaining two ships to receive the system in due course.73 Reports in September 2022 indicated that the Zumwalt had conducted it first deployment, albeit truncated, to Seventh Fleet’s Western Pacific area of operations.74

To reach 355 ships by 2034, the Navy plans several class-wide service life extensions, notably the extension of the DDG-51–class’s service life from 35 to 40 years and modernization of older hulls. The FY 2020 budget included $4 billion for modernization of 19 destroyers from FY 2021 through FY 2024.75 The previously noted planned decommissioning of five cruisers in FY 2023 makes this more critical.

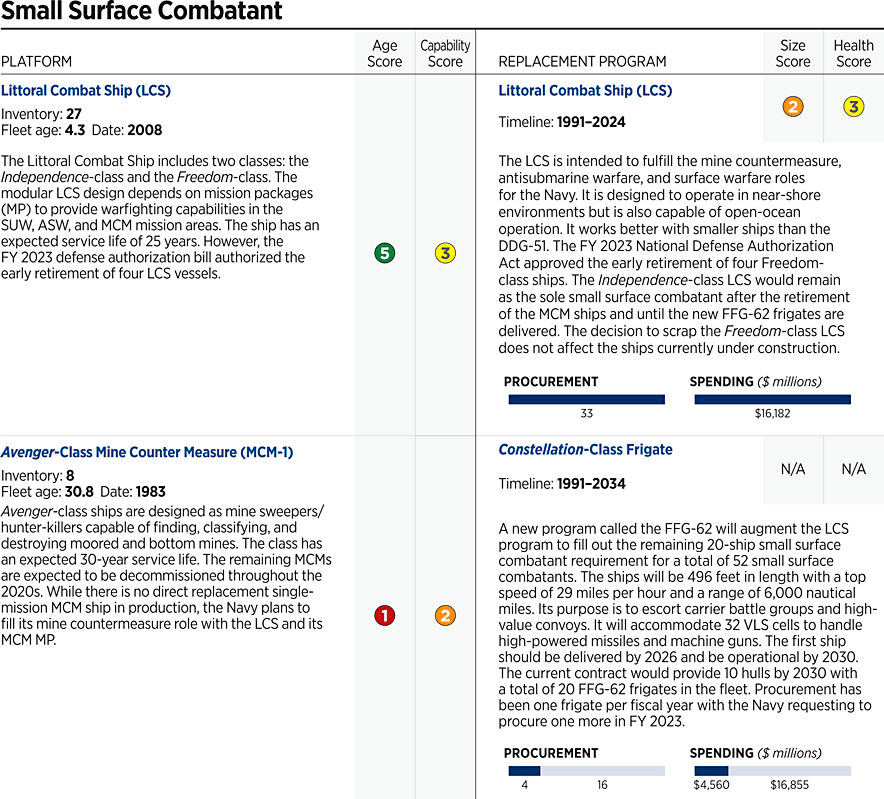

Small Surface Combatants. The Navy’s small surface combatants consist principally of the Avenger–class mine countermeasures (MCM) ship; the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS); and the Constellation–class frigate (FFG), which began production in 2021. In January 2021, the Navy halted production of the mono-hull LCS Freedom-variant until issues involving the design of its propulsion system are resolved. After that decision was made, in April 2023, the final Freedom variant was launched.76 In the meantime, the top speed of affected ships (currently 40-plus knots) is reportedly limited to 34 knots.77 Under the Navy’s FY 2020 30-year shipbuilding plan, the fleet of 23 LCSs was expected to grow to 34 and be joined by 18 frigates by FY 2034.78 Since then, the Navy has reversed course and terminated the LCS anti-submarine mission module program (10 units originally planned) and plans to decommission the remaining nine Freedom monohull variants.79

On August 20, 2020, the Navy decommissioned three of its aging Avenger–class MCM ships, leaving eight in service overseas in Sasebo, Japan, and Manama, Bahrain. These represent the only ship class dedicated to countering the mine threat.80 The current long-range shipbuilding plan confirms that the Navy intends to operate these aged MCMs through FY 2027.81

As these ships reach the end of their service life, the Navy is relying on the development of LCS mine countermeasure mission packages to provide this capability. At an April 2022 webinar, the CNO indicated that these mission modules were on track to reach IOC by the end of 2022.82 Since then, the Navy has canceled its ASW mission modules because of insurmountable engineering challenges, and on May 1, 2023, it announced that the MCM modules had achieved initial operational capability.83 In an unanticipated move, the Navy began to arm LCS with the naval strike missile, giving these ships a long-range anti-ship capability that they had lacked despite notable operations by the class in the South China Sea.84 On December 9, 2021, the San Diego-based Independence-variant Oakland received this new capability.85 Installation and procurement of surface warfare modules and associated surface-to-surface missile modules (LCS SSMM) is progressing; the procurement of 18 LCS SSMM planned for FY 2024 includes offensive and defense systems and associated munitions.86

Instead of requesting additional LCS, the Navy has focused on a new frigate. On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri a $795 million contract to build the lead ship of the new Constellation–class frigate at its Marinette Marine shipyard in Wisconsin based on a proven design currently in service with the French and Italian navies.87 While the design for the U.S. ship has not been finalized, the frigate is intended to be a multi-mission warship with 32 VLS cells, as many as 16 containerized naval strike missiles (NSM), and one helicopter.88 As of June 2023, 90 percent of function design and 80 percent of detail design work had been completed despite construction having already begun with some risk of program delay and cost increase.89 In May 2021, the Navy contracted for the second ship in the class, the USS Congress (FFG-63).90 The Navy purchased a third ship in FY 2022 and plans to purchase two more in FY 2024. The Navy has awarded Fincantieri a $526 million contract for a fourth frigate, but a decision for a second shipyard to begin construction of frigates that was to be made in FY 2023 has been delayed, and this could affect future production rates.91

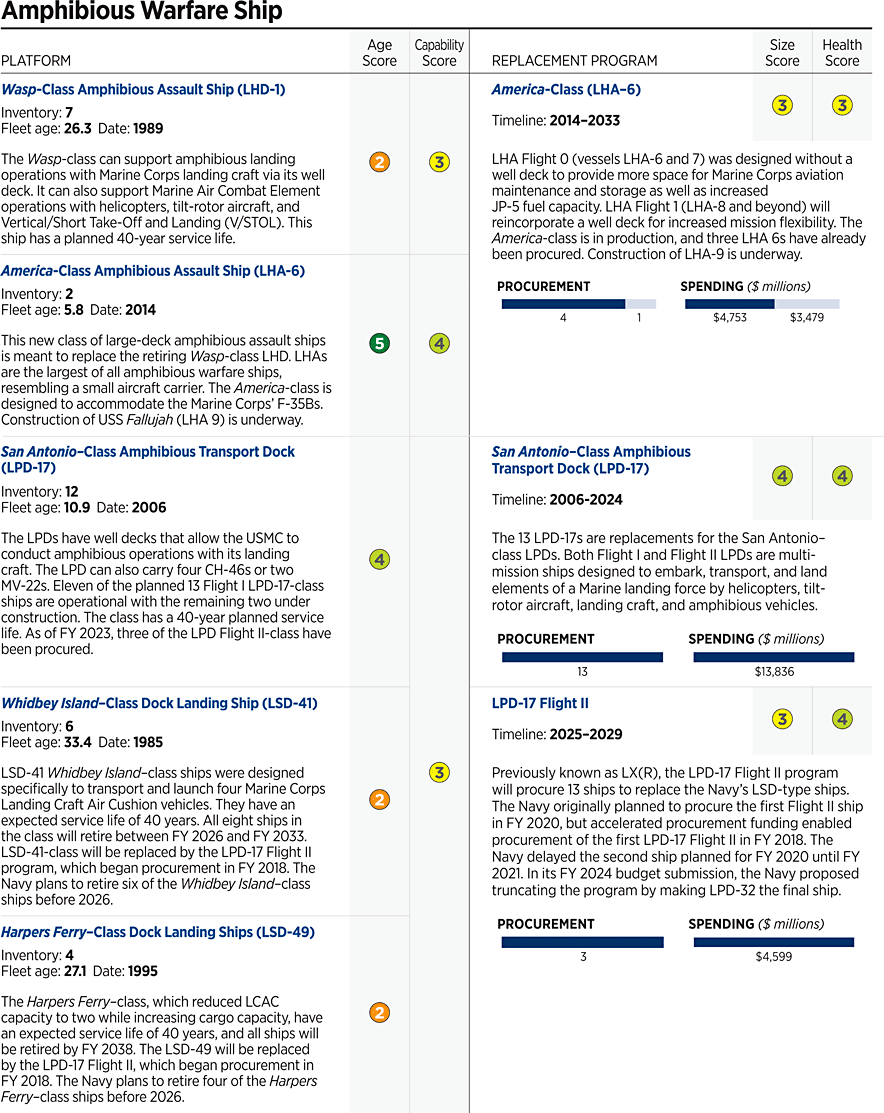

Amphibious Ships. Commandant of the Marine Corps General David Berger issued his “Commandant’s Planning Guidance” in July 2019 and “Force Design 2030” in March 2020. Both documents signaled a break with past Marine Corps requests for amphibious lift, specifically moving away from the requirement for 38 amphibious ships to support an amphibious force of two Marine Expeditionary Brigades (MEB).92 The Commandant envisioned a larger yet affordable fleet of smaller, low-signature amphibious ships—the Landing Ship Medium (LSM)93—that enable littoral maneuver and associated logistics support in a contested theater.94 However, the amphibious fleet remains centered on fewer large ships. This vision remains years away from being realized with Congress holding the line at “not less than 31 operational amphibious warfare ships.”95

The Navy’s Future Naval Force Study (FNFS)96 and December 2020 30-year shipbuilding plan acknowledged the growing importance of the LSM, which will have to be produced rapidly and in sufficient numbers in order to actualize the naval forces’ distributed concepts of operations (for example, Marine Littoral Regiments and Distributed Maritime Operations). According to the April 2022 long-range shipbuilding plan, the Navy intends to purchase the first LSM in FY 2025. The Marine Corps had intended to have the ship under contract by the summer of 2022, but because of delays, it has begun to use alternative platforms to train and work out operational concepts so that it will be ready when the ship eventually is delivered.97

As of September 2023, the Navy had nine amphibious assault ships in the fleet (seven Wasp–class LHD and two America–class LHA); 12 amphibious transport docks (LPD); and 10 dock landing ships (LSD).98 The FY 2021 budget included $250 million in additional funds to accelerate construction of LHA-9 following the July 2020 catastrophic fire on Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6).99 The decision to decommission the damaged ship further exposed limitations in shipyard capacity, as repairs would have had a negative effect on other planned shipbuilding and maintenance.100 In December 2022, construction began on the USS Fallujah (LHA-9), which, like the Bonhomme Richard, is to be configured for F-35B joint strike fighters and MV-22 Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft, at a cost of $2.4 billion.101

The Navy’s LSDs, the Whidbey Island–class and Harpers Ferry–class amphibious vessels, are scheduled to reach the end of their 40-year service lives beginning in 2025. The USS Harrisburg (LPD-30) of the San Antonio–class Landing Platform Dock amphibious ships began construction in April 2020 and when delivered will be the first of 13 San Antonio–class Flight II ships to replace the legacy LSD ships. The 12th first flight San Antonio–class ship (LPD 28) was delivered six months later than reported in the 2022 Index.102

The FY 2021 budget included $500 million “to maximize the benefit of the amphibious ship procurement authorities provided elsewhere in this Act through the procurement of long lead material for LPD-32 and LPD-33.”103 The Navy’s FY 2023 budget funded LPD-32 with a $1.295 billion contract for the ship’s construction.104 LPD-32 is the most recently purchased of the 13 Flight IIs that were originally envisioned. The Marine Corps has sought procurement of LPD-33 and has kept it at the top of its unfunded requirements list.105 The three-way dispute among the Secretary of Defense’s staff, the Navy, and the Marine Corps over the future of the large amphibious warship fleet remains contentious and unresolved.106

Unmanned Systems. The Navy does not include unmanned ships in counting its battle force size. Previous long-range shipbuilding plans envisioned the purchase of 13 Large Unmanned Surface Vessels (LUSV); one Medium Unmanned Surface Vessel (MUSV); and eight Extra Large Undersea Unmanned Vessels (XLUUV) by FY 2026.107 The Navy continues to test and evaluate seven prototype unmanned platforms, five of which are to be delivered by FY 2028. Additionally, current plans call for procurement of the LUSV to begin in FY 2025 and increase to three per year beginning in FY 2027.108 On May 18, 2021, an experimental LUSV, the Nomad, transited the Panama Canal on its way to Surface Development Squadron (SURFDESRON) 1 based in California.109 SURFDESRON 1 operates MUSV Sea Hunter prototypes, LUSV, and the Zumwalt destroyer to advance the Navy’s unmanned surface warship capabilities.110 Since publication of the 2023 Index, the Navy has made notable progress with its unmanned fleet.

The Navy reached a significant milestone in September 2021 when its small fleet of unmanned surface ships launched and hit a target with an SM-6 interceptor missile.111 After years in a laboratory and in controlled at-sea navigational tests, unmanned ships are now deploying in operational settings. That same month, Task Force 59, based in the Persian Gulf and comprised of smaller unmanned drones and vessels, conducted International Maritime Exercise 2022 (IMX22), an exercise in the Red Sea that involved 10 nations and more than 80 unmanned platforms.112 In a sign of growing confidence, the Navy announced that it will establish a similar unmanned vessel task force at Fourth Fleet based in Mayport, Florida.113

Logistics, Auxiliary, and Expeditionary Ships. Expeditionary support vessels are highly flexible platforms of two types: those used for prepositioning and sustaining forward operations and others used for high-speed lift in uncontested environments. The Navy has five of the former (two Expeditionary Transfer Dock [ESD] and three Expeditionary Sea Base [ESB] vessels) and 12 of the latter (shallow-draft Expeditionary Fast Transport [EPF] vessels). In March and April 2022, ESB Hershel Williams (ESB 4) demonstrated the versatility of these ships during maritime security missions with African coast guards and navies. In August 2021, it conducted a counter-piracy exercise with the Brazilian navy. At the same time, China was attempting to secure a base in Equatorial Guinea.114 The Navy christened ESB 6, USNS John L. Canley, on June 25, 2022.115 ESB 7, USNS Robert E. Simanek, is currently under construction in San Diego, California, with its keel having been laid in October 2021.116

With their shallow draft and versatile cargo capacity, EPFs offer unique capabilities that are well suited to austere but uncontested waters. Specifically, these ships can transport 600 short tons of military cargo (for example, main battle tanks) 1,200 nautical miles at 35 knots. The Navy christened its 13th EPF, the USNS Apalachicola, on November 13, 2021, and construction is progressing.117 In March 2021, the Navy revised its contract with Austal USA for $235 million to modify EPF 14 and the future EPF 15 to enable them to serve as high-speed hospital ships with the capability of embarking a V-22 tilt-rotor aircraft.118 The keel for EPF 14 configured as a hospital ship was laid on January 26, 2022, and construction of EPF 15 in the same configuration commenced the same month.119 EPF 14, USNS Cody, was launched on March 20, 2023.120

The Navy’s Combat Logistics Force (CLF) includes dry-cargo and ammunition ships (T-AKE); fast combat support ships (T-AOE); and oilers (AO). The CLF provides critical support, including at-sea replenishment, that enables the Navy to sustain the fleet at sea for prolonged periods. The Navy’s future oiler John Lewis (T-AO 205) was procured in 2016 and launched five years later on January 12, 2021; 20 ships of this class are planned.121 However, because of a flooding incident at the graving dock, delivery of John Lewis was delayed, and this in turn caused cascading delays of 12 to 15 months in construction of the second through sixth ships.122 The lead ship of the class, John Lewis, was delivered to the Navy in July 2022, and three ships of the class are currently under construction.123

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s March 7, 2022, decision to dismantle Red Hill fuel storage facilities in Hawaii will generate additional pressure to increase the Navy’s at-sea oiler fleet to meet operational needs in the Pacific. A plan specifying how the Navy will mitigate the loss of these massive Pacific fuel storage facilities was due by May 31, 2022.124 As of June 16, 2023, the details of this plan had not been made public, and it remains uncertain, given delays in the construction of oilers, exactly how the fleet’s operational energy needs will be met.125

Strike Platforms and Key Munitions. The FY 2024 budget continues the Navy’s focus on long-range offensive strikes launched from ships, submarines, and aircraft. Notable capability enhancements include, for example, Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS), a maneuverable hypersonic non-nuclear weapon for long-range strikes that receives support for initial deployment on the Zumwalt–class destroyer in FY 2025, and upgraded Block V Maritime Strike Tomahawk (MST) kits with improved targeting, procurement of which is entering its fourth year.126

To counter the threat posed by the Chinese PL-15 long-range air-to-air missile, which has an operational range of 186 miles, the Navy is working with the Air Force to develop the AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range missile, the operational range of which has not been made public.127 In March 2021, the Air Force reported a record long-range kill of a drone target by this developmental missile from one of its F-15C fighters.128 If this report is accurate, it indicates development of a critical capability, but little reporting on progress has been noted since the 2023 Index.

Shore-Based Anti-Ship Capabilities. Following the August 2019 U.S. withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, new intermediate-range (500–1,000 miles) conventional ground-launched strike options became politically viable. This is especially important in Asia where such capable missiles deployed to the first island chain would have great relevance in any conflict with China.129

The FY 2020 budget included $76 million to develop ground-launched cruise missiles.130 The FY 2021 budget included an additional $59.6 million to procure 36 ground-based anti-ship missiles.131 The FY 2023 budget funded low-rate initial production of 115 Naval Strike Missiles and associated development of Marine Corps platoon-level targeting systems.132 The FY 2024 budget, building on recent successes, continues upward investment in development and increased production of these weapon systems: $363.5 million for the Navy–Marine Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System (NMESIS) anti-ship missile; 34 shore-launched tactical Tomahawk missiles; and 90 Naval Strike Missiles.133 A photo of the launch of a U.S. Marine Corps truck-mounted Naval Strike Missile—ostensibly part of NMESIS—was released in April 2021, revealing efforts to introduce this weapon capability across naval forces.134 Ukraine’s use of shore-based anti-ship missiles to sink Russia’s Black Sea flag ship, the Moskva, in April 2022 has sparked renewed interest in such systems.

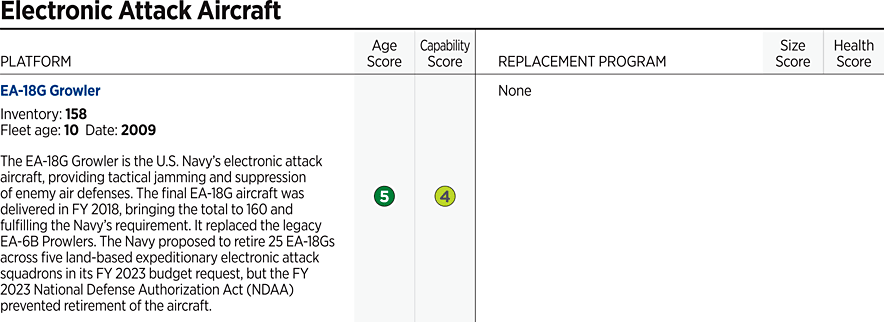

Electronic Warfare (EW). The purpose of electronic warfare is to control the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) by exploiting, deceiving, or denying its use by an enemy while ensuring its use by friendly forces. It is therefore a critical element of successful modern warfare. The final dedicated EW aircraft, the EA-18G Growler, was delivered in July 2019, meeting the Navy’s requirement to provide this capability to nine carrier air wings (CVW), five expeditionary squadrons, and one reserve squadron.135 Anticipating the EA-18G’s retirement in the 2030s, the Navy has been exploring follow-on manned and unmanned systems, but no new developments on a replacement have been reported since publication of the 2023 Index. To ensure that the EA-18G remains relevant on the battlefield until 2030, an anticipated upgrade or Block II modification with the improved Next Generation Electronic Attack Unit (NGEAU) is being pursued.

The Navy’s earlier proposal to retire all of its expeditionary electronic attack squadrons by FY 2025 came as a surprise.136 Unless there is a replacement capability, retirement of these aircraft removes the EW coverage provided by these units from forward airfields, shifting the support burden to nearby naval platforms and the other services. Given this uncertainty, Congress stipulated in the FY 2023 NDAA that the Secretary of the Navy may not retire an EA-18G aircraft until September 30, 2027, and required that no later than 180 days after the NDAA’s enactment, “the Secretary of the Navy and the Secretary of the Air Force shall jointly submit to the congressional defense committees a report that includes a strategy and execution plan for continuously and effectively meeting the airborne electronic attack training and combat requirements of the joint force.”137 The status of that report is unknown.

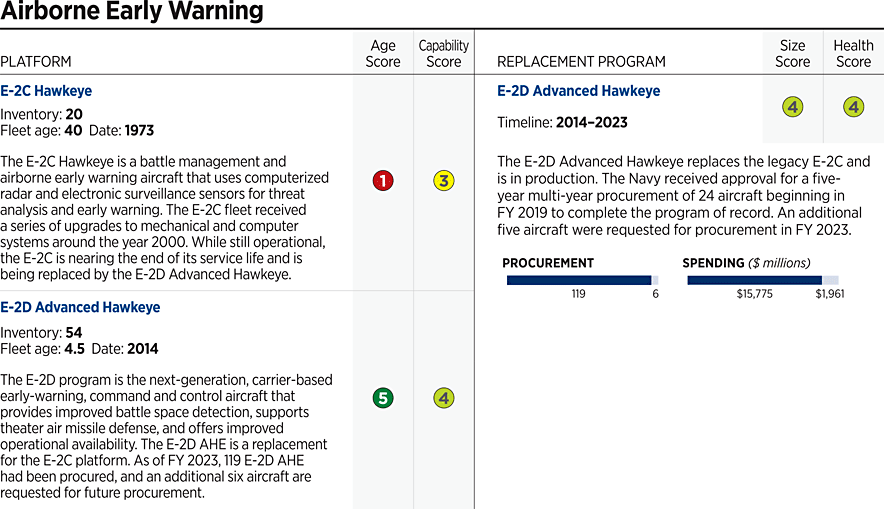

Air Early Warning. The E-2D forms the hub of the Naval Integrated Fire Control Counter Air (NIFC-CA) system and provides critical theater air and missile defense capabilities. The Navy’s FY 2021 budget supported the procurement of four aircraft with an additional 10 to be procured over the following two years.138 The FY 2023 budget completed this plan by including procurement of the final five new E-2D aircraft, which are important air control platforms.

High Energy Laser (HEL). HEL systems provide the potential to engage targets or shoot down missiles without being limited by how much ammunition can be carried onboard ship. A significant milestone was achieved when USS Portland (LPD-27) used its HEL Weapon System Demonstrator to shoot down an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) over the Pacific on May 16, 2020.139 This was followed by the Navy’s decision to begin installation of a HEL system—the High-Energy laser with Integrated Optical Dazzler and Surveillance (HELIOS) (60 kW) laser140—on destroyers in 2021 beginning with the USS Preble.141 HELIOS is a scalable laser system that is integrated into the ship’s weapons control and radar systems and can dazzle and confuse threats, disable small boats, or shoot down smaller air threats. The Navy’s FY 2024 budget will sustain the installation of HELIOS on the USS Preble and develop a 100 kW HEL demonstrator system on the USS Portland, representing modest investment and progress.142

In April 2022, the Navy demonstrated the ability of its Layered Laser Defense HEL system to shoot down a drone simulating a cruise missile.143 Successful tests like this and the ongoing deployment of the HELIOS on the destroyer Preble will be followed by installation of a much stronger 100 kW laser on Portland (LPD-27) that approaches the power needed for missile defense.144 However, until field testing against meaningful threat platforms is conducted across a range of weather conditions, the effectiveness of such systems will remain unproven.

Command and Control. Networked communications are essential to successful military operations. The information passed over these networks includes sensitive data on such subjects as targeting and logistics, and this makes cyber security, communications, and the information systems that generate and relay this information critical elements of the DOD information enterprise.

On October 1, 2020, CNO Michael Gilday signed two memos establishing Project Overmatch. The goal of Project Overmatch was to achieve situational awareness and effective command and control of a geographically dispersed naval force. In his two memos, the CNO directed that investments be made to deliver network architectures, unmanned capabilities, and data analytics to ensure that the Navy can operate and dominate in a contested environment.145 The CNO also directed the Navy to leverage related Air Force efforts on the Joint All-Domain Command and Control program (JADC2),146 now a Joint Force effort involving all of the military branches.

Remarkably, despite the significance of the effort, little has been publicly released on Project Overmatch; what is known is that it involves three classified funding lines with initial deployment or program capabilities slated for 2023.147 In unofficial venues, it has been hinted that the first platform to employ JADC2 capabilities will be an aircraft carrier, but public statements indicate that the objective is to connect all platform data flows from across the U.S. Joint Force (potentially including partner forces), analyze them for classification, and make predictive targeting recommendations. If successful, artificial intelligence paired with resilient communications and “big data” analytics might enable a key element of Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO).

Readiness

In the 1980s, the Navy had nearly 600 ships in the fleet and kept roughly 100 (17 percent) deployed at any one time. As of June 10, 2023, the fleet’s OPTEMPO was 28 percent. With fewer ships carrying an unchanging operational workload, training schedules become shorter and deployments become longer. The commanding officer’s discretionary time for training and crew familiarization is a precious commodity that is made scarcer by the increasing operational demands on fewer ships.

FY 2019 marked the first time in more than a decade that DOD and the Navy did not have to operate under a continuing resolution for at least part of the fiscal year. Having a full fiscal year to plan and execute maintenance and operations helped the Navy to continue on its path to restoring fleet readiness. CNO Admiral John Richardson explained to the Senate Armed Services Committee in April 2018 that it would take until late 2021 or 2022 to restore fleet readiness to an “acceptable” level if adequate funding was maintained; without “stable and adequate funding,” it would take longer.148 Unfortunately, the Navy began FY 2020 under another continuing resolution that delayed planned maintenance for the USS Bainbridge (DDG 96) and USS Gonzalez (DDG 66), revealing yet again that for the Administration and Congress, the need to correct deficiencies in America’s naval power was not enough to ensure that they delivered a budget on time.149

Given this recent history and the demands of unplanned and urgently needed ship repairs brought about by such incidents as the grounding of the submarine Connecticut, the Navy remains deficient in its ability to return ships to sea.

Impact of COVID-19. The eruption of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused many problems for the U.S. Navy. The USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71), for example, was forced to quarantine for 55 days in Guam; the major biannual international Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) was scaled down; 1,629 reservists were called to active duty to backfill high-risk shipyard workers conducting critical maintenance; and the Navy was restricted to using “safe haven” COVID-free ports. In May 2021, the CNO assessed that the Navy managed the pandemic with minimal operational impact but with added time at sea and delays for family reunions pending quarantines.150

As the pandemic recedes, the Navy’s response to account for and mitigate the effects of COVID-driven restrictions has been a success overall. According to the Navy’s February 10, 2023, final COVID report, total cumulative COVID cases among active-duty uniformed Navy personnel numbered 109,310 with 17 deaths, 3,350 unvaccinated servicemembers remaining on active duty, and a total of 1,878 sailors separated for refusing the vaccine; previous reporting indicated that 214 religious waivers were granted.151 Given vaccination rates and ebbing danger, the Navy appears to be past the COVID epidemic. Ideally, the Navy would implement lessons learned from this experience to prepare for future pandemics and biological attacks, but there is as yet little evidence that the service has conducted such a study, implemented new pandemic guidelines, or sought new capabilities to combat a future pandemic.

Maintenance and Repairs. Naval Sea Systems Command completed its Shipyard Optimization and Recapitalization Plan in September 2018.152 Four years later, the improvement of public shipyard capacities is still just beginning. It was expected that the initial step—building digital models to inform future upgrades to the Navy’s four public shipyards—would be complete by the end of 2021, but it remained incomplete as of June 2022.

Attempts by Congress to accelerate the effort have not been effective.153 At a May 10, 2022, Senate hearing, it became apparent both that the original costs were significantly underestimated and that timelines are slipping. During that hearing, the Government Accountability Office reported that:

- “[F]rom 2017 to 2020, the backlog of restoration and modernization projects at the Navy shipyards has grown by over $1.6 billion, an increase of 31 percent.”154

- “In 2018, the Navy estimated that it would need to invest about $4 billion in its dry docks to obtain the capacity to perform the 67 availabilities it cannot currently support. This estimate included 14 dry dock projects planned over [a] 20-year span. However…the Navy’s first three dry dock projects have grown in cost from an estimated $970 million in 2018 to over $5.1 billion in 2022, an increase of more than 400 percent.”155

- “In a 2021 report to Congress, the Navy stated it would complete the [Area Development Plans] by fiscal year 2021. However, in a September 2021 update of that report, the Navy stated the ADPs would be complete four years later, in fiscal year 2025.”156

More recently, the GAO assessed the Navy’s readiness from 2017 through 2021. Because of persistent problems, the Navy’s readiness was assessed as degrading: Ship maintenance backlogs were estimated at $1.8 billion, conditions at public shipyards remained poor, and enduring issues of crew shortfalls and fatigue delayed maintenance activities.157 On top of this, new reports indicate that 37 percent of the Navy’s submarine force is unavailable in FY 2023 for missions at sea because of maintenance backlogs; a more normal rate would be 20 percent.158

Training, Ranges, and Live-Fire Exercises. Ship and aircraft operations and training are critical to fleet readiness. The Navy has sought to meet fleet readiness requirements by funding 58 underway days for each deployed warship and 24 underway days for each non-deployed warship per fiscal quarter. The Navy’s proposed budget would fall short of these goals by funding 97 percent of ship operations, 90 percent of flight hours, and 87 percent of facilities sustainment.159 Less clear is how much of this time is spent on crew training and whether the Navy assesses this as effective in meeting needed operational proficiencies.

To improve warfighting proficiency, the Navy is seeking to expand and update instrumentation of the training range at Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada, to enable practice with the most advanced weapon systems.160 This training range fits into the larger five-year $27.3 billion Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) that, led by Indo Pacific Command, is intended partly to transform the way the Navy trains for high-end conflict and improve training with U.S. allies in the Pacific.161 Of particular importance to the Navy are PDI investments to modernize the Pacific Missile Range Facility (PMRF); the Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex (JPARC); and the Combined/Joint Military Training (CJMT) Commonwealth Northern Mariana Islands in order to improve training for operations across all domains: air, land, sea, space, and cyber.162

The FY 2024 budget earmarks $9.1 billion of DOD’s topline budget for PDI ($3 billion more than in FY 2023). Especially important are long lead time infrastructure projects in Guam and Tinian in the northern Marianas. This year’s PDI budget includes $3.25 billion for the Navy: $1.15 billion for operations, $14.6 million for logistics, $313.3 million for exercises, $1.58 billion for infrastructure investments, $42.8 million for added staffing, and $146.7 million to improve partner nations’ capabilities.163 To measure the effectiveness of these investments, the Navy will need to demonstrate increased frequency of exercises that practice high-end warfighting independently, jointly, and with such key allies as Australia, Japan, and South Korea. This should include increased numbers of realistic free-play events and increased by-hull frequency of live-fire drills.

Finally, not forgotten are the 2017 collisions of the USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) and USS Fitzgerald (DDG 62) in which 17 sailors were lost. Findings of the subsequent investigations, which highlighted the importance of operational risk management and unit readiness, remain relevant.164 To ensure that these tragic events are not repeated, the Secretary of the Navy’s Strategic Readiness Review made several broad institutional recommendations:

- “The creation of combat ready forces must take equal footing with meeting the immediate demands of Combatant Commanders.”

- “The Navy must establish realistic limits regarding the number of ready ships and sailors and, short of combat, not acquiesce to emergent requirements with assets that are not fully ready.”

- “The Navy must realign and streamline its command and control structures to tightly align responsibility, authority, and accountability.”

- “Navy leadership at all levels must foster a culture of learning and create the structures and processes that fully embrace this commitment.”165

A reminder that the above recommendations remain relevant was the October 2021 grounding of the submarine Connecticut in the South China Sea. The subsequent investigation found the event avoidable while operating in poorly surveyed waters—a reminder of the risk as well as the vigilance required at sea.166

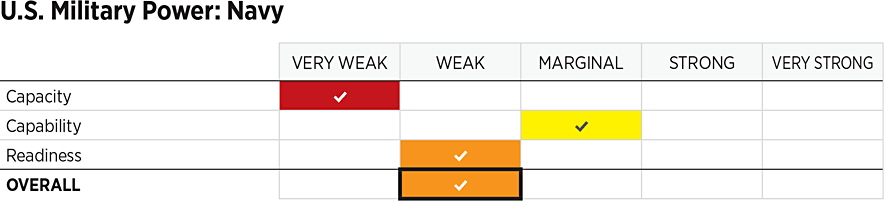

Scoring the U.S. Navy

Capacity Score: Very Weak

This Index assesses that the Navy needs a battle force consisting of 400 manned ships to do what is expected of it today. The Navy’s current battle force fleet of 298 ships and intensified operational tempo combine to reveal a service that is much too small relative to its tasks. Contributing to a lower assessment is the Navy’s persistent inability to arrest and reverse the continued diminution of its fleet as adversary forces grow in number and capability. If it continues on its current trajectory, the Navy will shrink further to 280 ships by 2037. Depending on the Navy’s ability to realize aggressive growth, reverse early decommissioning plans, increase its end strength, and develop creative service life extensions, its capacity score will probably remain “very weak” for the foreseeable future.

Capability Score: Marginal Trending Toward Weak

The overall capability score for the Navy remains “marginal” with downward pressure as the Navy’s technological edge narrows against peer competitors China and Russia. The combination of a fleet that is aging faster than old ships are being replaced and the rapid growth of competitor navies with modern technologies has only intensified the danger for U.S. naval power. Without meaningful progress in fielding systems that are able to defend against an array of threats, greater integration of unmanned systems into the fleet, and development of a family of new long-range weapons, especially in air-to-air combat, the Navy’s capability score could well decline to “weak” in the 2025 Index.

Readiness Score: Weak

The Navy’s readiness score remains “weak.” This is due primarily to the Navy’s persistent struggle to recapitalize antiquated, inadequate maintenance infrastructure and workforce to meet current needs. The effectiveness of training and exercises measured against China will be an increasingly critical metric in this score.

Overall U.S. Navy Score: Weak

The Navy’s overall score in the 2023 Index is “weak,” driven by lower scores in capacity and readiness. To correct this trend, the Navy will have to eliminate several readiness and capacity bottlenecks while seeing to it that America has an operational fleet with the numbers and capabilities postured to counter Russian and Chinese naval advances. There is added urgency given both that China is aggressively posturing itself to obtain maximum advantage over Taiwan and that many of the U.S. Navy’s efforts to improve itself will take several years to achieve the desired results.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy FY 2024 President’s Budget,’” PowerPoint Presentation, March 10, 2023, p. 3, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Mar/29/2003188745/-1/-1/0/DON_PRESS_BRIEF.PDF (accessed September 5, 2023). “In December 2022, the Secretary of the Navy, Carlos Del Toro, shared the following during his remarks at Columbia University: “First, we are strengthening our maritime dominance so that we can deter potential adversaries, and if called upon, fight and win our Nation’s wars. Second, we are building a culture of warfighting excellence, founded on strong leadership, that is rooted in treating each other with dignity and respect. And third, we are enhancing our strategic partnerships, across the Joint Force, with industry, with academia, and with our Allies and partners around the globe.” U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Budget–2023, Highlights of the Department of the Navy FY 2024 Budget, pp. 1-4–1-5, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Mar/29/2003188749/-1/-1/0/HIGHLIGHTS_BOOK.PDF (accessed September 2, 2023). Italics in original.

[2] U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Budget–2023, “Highlights of the Department of the Navy FY 2024 Budget,” DON Budget Card, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Mar/29/2003188744/-1/-1/0/DON_BUDGET_CARD.PDF (accessed September 2, 2023).

[3] Sam LaGrone and Mallory Shelbourne, “Navy Closes 4 Puget Sound Submarine Dry Docks Following Earthquake Risk Study,” U.S. Naval Institute News, January 27, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/01/27/navy-closes-4-puget-sound-submarine-dry-docks-following-earthquake-risk-study (accessed September 1, 2023).

[4] Sam LaGrone, “Investigation Concludes USS Connecticut Grounded on Uncharted Seamount in South China Sea,” U.S. Naval Institute News, updated May 24, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2021/11/01/investigation-concludes-uss-connecticut-grounded-on-uncharted-sea-mount-in-south-china-sea (accessed September 1, 2023), and Sam LaGrone, “Investigation: USS Connecticut South China Sea Grounding Result of Lax Oversight, Poor Planning,” U.S. Naval Institute News, May 24, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/05/24/investigation-uss-connecticut-south-china-sea-grounding-result-of-lax-oversight-poor-planning (accessed September 1, 2023).

[5] Table, “Final Report—As of Feb. 10, 2023,” in U.S. Navy, “COVID-19 Updates: Navy COVID-19 Update,” February 10, 2023, https://www.navy.mil/Resources/COVID-19-Updates/ (accessed September 1, 2023).

[6] “Remarks by President Biden, Prime Minister Albanese of Australia, and Prime Minister Sunak of the United Kingdom on the AUKUS Partnership,” The White House, March 13, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/03/13/remarks-by-president-biden-prime-minister-albanese-of-australia-and-prime-minister-sunak-of-the-united-kingdom-on-the-aukus-partnership/ (accessed September 1, 2023).

[7] Mallory Shelbourne, “Navy Exporting Middle East Unmanned Template to SOUTHCOM to Curb Illegal Fishing, Battle Drug War,” U.S. Naval Institute News, April 5, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/04/05/navy-exporting-middle-east-unmanned-template-to-southcom-to-curb-illegal-fishing-battle-drug-war (accessed September 1, 2023).

[8] U.S. Department of the Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Coast Guard, Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with All-Domain Naval Power, December 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Dec/17/2002553481/-1/-1/0/TRISERVICESTRATEGY.PDF/TRISERVICESTRATEGY.PDF (accessed September 5, 2023).

[9] See The Heritage Foundation, “The New 2020 Tri-Service Maritime Strategy—‘Advantage at Sea,’” Factsheet No. 195, January 19, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/FS_195_0.pdf.

[10] U.S. Naval Institute News, “Category Archives: Fleet Tracker,” https://news.usni.org/category/fleet-tracker/page/3 (accessed September 1, 2023).

[11] President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., National Security Strategic Guidance, The White House, October 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

[12] U.S. Department of Defense, “Fact Sheet: 2022 National Defense Strategy,” transmitted to Congress March 28, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964702/-1/-1/1/NDS-FACT-SHEET.PDF (accessed September 1, 2023).

[13] The Global Force Management Allocation Plan (GFMAP) is a classified document that specifies forces to be provided by the services for use by operational commanders. It is an extension of a reference manual maintained by the Joint Staff, Global Force Management Allocation Policies and Procedures (CJCSM 3130.06B), which is also a classified publication. See U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Adaptive Planning and Execution Overview and Policy Framework,” unclassified Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Guide 3130, March 5, 2019, p. B-2, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Library/Handbooks/CJCS%20GUIDE%203130.pdf?ver=2019-03-18-122038-003 (accessed September 1, 2023).

[14] Admiral M. M. Gilday, Chief of Naval Operations, Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan 2022, released July 26, 2022, pp. 3 and 7–9, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Jul/26/2003042389/-1/-1/1/NAVIGATION%20PLAN%202022_SIGNED.PDF (accessed September 1, 2023).

[15] U.S. Navy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities–OPNAV N9, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2024, March 2023, https://www.govexec.com/media/navy_2024_shipbuilding_plan.pdf (accessed September 3, 2023).

[16] Sam LaGrone, “Navy Raises Battle Force Goal to 381 Ships in Classified Report to Congress,” U.S. Naval Institute News, July 18, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/07/18/navy-raises-battle-force-goal-to-381-ships-in-classified-report-to-congress (accessed September 1, 2023).

[17] U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Navy, Office of the Secretary, “General Guidance for the Classification of Naval Vessels and Battle Force Ship Counting Procedures,” SECNAV Instruction 5030.8C, June 14, 2016, pp. 1–2, http://www.nvr.navy.mil/5030.8C.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

[18] Thomas Callender, “The Nation Needs a 400-Ship Navy,” Heritage Foundation Special Report No. 205, October 26, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/the-nation-needs-400-ship-navy. For an analysis regarding future force design out to 2035, see Brent D. Sadler, “Rebuilding America’s Military: The United States Navy,” Heritage Foundation Special Report No. 242, February 18, 2021, pp. 3–5, 7, 71, 75, and 83, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/rebuilding-americas-military-the-united-states-navy.

[19] The full array of aircraft comprising a carrier air wing also includes one EA-18G Growler electronic attack squadron, one E-2D Hawkeye airborne early warning squadron, two SH-60 Seahawk helicopter squadrons, and one C-2 Greyhound logistics support squadron.

[20] U.S. Navy, “Executive Summary: 2016 Navy Force Structure Assessment (FSA),” December 15, 2016, p. 2, http://static.politico.com/b9/99/0ad9f79847bf8e8f6549c445f980/2016-navy-force-structure-assessment-fsa-executive-summary.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023). The full FSA was not released to the public. In July 2019, the Marine Corps cancelled the requirement for 38 amphibious ships as a formal force-sizing demand for the Navy. General David H. Berger, Commandant of the Marine Corps, stated his belief that future naval warfare and the Marine Corps’ role in it against a peer competitor will require new types of smaller vessels that will be harder for an enemy to find and target, as well as able to support an evolving concept of distributed naval warfare more effectively, and that can be purchased in greater quantity at a lower price per vessel. Nevertheless, the long-standing 38-ship requirement has informed Navy shipbuilding plans and remains a central factor in current ship acquisition contracts. See General David H. Berger, Commandant of the Marine Corps, “Commandant’s Planning Guidance ,” U.S. Department of the Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, released July 17, 2019, p. 4, https://www.hqmc.marines.mil/Portals/142/Docs/%2038th%20Commandant%27s%20Planning%20Guidance_2019.pdf?ver=2019-07-16-200152-700 (accessed September 1, 2023).

[21] Matthew Hipple, “20 Years of Naval Trends Guarantee a FY23 Shipbuilding Plan Failure,” Center for International Maritime Security, May 9, 2022, https://cimsec.org/20-years-of-naval-trends-guarantee-a-fy23-shipbuilding-plan-failure/ (accessed September 1, 2023).

[22] Sam LaGrone and Mallory Shelbourne, “CNO Gilday: ‘We Need a Naval Force of Over 500 Ships,’” U.S. Naval Institute News, February 18, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/02/18/cno-gilday-we-need-a-naval-force-of-over-500-ships (accessed September 1, 2023).

[23] Bryan Clark and Jesse Sloman, Deploying Beyond Their Means: America’s Navy and Marine Corps at a Tipping Point, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, November 18, 2015, pp. 5–8, https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA6174_(Deploying_Beyond_Their_Means)Final2-web.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

[24] Daniel Whiteneck, Michael Price, Neil Jenkins, and Peter Swartz, The Navy at a Tipping Point: Maritime Dominance at Stake? Center for Naval Analyses, CAB D0022262.A3/1REV, March 2010, p. 7, https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/D0022262.A3.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

[25] Megan Eckstein, “No Margin Left: Overworked Carrier Force Struggles to Maintain Deployments After Decades of Overuse,” U.S. Naval Institute News, November 12, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/11/12/no-margin-left-overworked-carrier-force-struggles-to-maintain-deployments-after-decades-of-overuse (accessed September 1, 2023).

[26] Operational Tempo (OPTEMPO) is the rate at which a warship is involved in military activities like exercises, presence operations, or training versus time in port for maintenance. For the numbers as of August 31, 2023, see U.S. Navy, Office of Information, “Status of Ships Underway August 31, 2023,” https://www.navy.mil/About/Mission/ (accessed September 1, 2023).

[27] U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Coast Guard, Naval Operations Concept 2010: Implementing the Maritime Strategy, p. 26, https://fas.org/irp/doddir/navy/noc2010.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

[28] On average, rotational deployments require four ships for one ship to be forward deployed. This is necessary because one ship is sailing out to a designated location, one is at location, one is sailing back to the CONUS, and one is in the CONUS for maintenance.

[29] Figure 4, “Comparison of Forward-Presence Rates Provided on an Annual Basis for Ships Homeported in the United States and Overseas,” in U.S. Government Accountability Office, Navy Force Structure: Sustainable Plan and Comprehensive Assessment Needed to Mitigate Long-Term Risks to Ships Assigned to Overseas Homeports, GAO-15-329, May 2015, p. 13, https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670534.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

[30] See H.R. 2810, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018, Public Law 115-91, 115th Cong., December 12, 2017, Section 1025, https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ91/PLAW-115publ91.pdf (accessed September 5, 2023). Though dating to 2017, this requirement has not been adjusted, thus serving as the legal reference point for the mandated size, or objective, of the Navy’s fleet.

[31] See H.R. 5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, Public Law 115-232, 115th Cong., August 13, 2018, Section 123, https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ232/PLAW-115publ232.pdf (accessed September 2, 2023).

[32] Paul McLeary, “Navy Scraps Big Carrier Study, Clears Desk for OSD Effort,” Breaking Defense, May 12, 2020, https://breakingdefense.com/2020/05/navy-scraps-big-carrier-study-clears-deck-for-osd-effort/ (accessed September 2, 2023).

[33] Press release, “Sullivan Blasts U.S. Navy for Violating Law, Putting American Lives at Risk,” Office of U.S. Senator Dan Sullivan, May 4, 2023, https://www.sullivan.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/sullivan-blasts-us-navy-for-violating-law-putting-american-lives-at-risk (accessed September 2, 2023).

[34] Transcript, “House Armed Services: Department of the Navy FY2024 Budget Request,” U.S. Navy Office of Information, April 28, 2023, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Testimony/display-testimony/Article/3380268/house-armed-services-department-of-the-navy-fy2024-budget-request/ (accessed September22, 2023). See also video, “Full Committee Hearing: ‘Department of the Navy Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Request,’” Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives April 28, 2023, https://armedservices.house.gov/hearings/full-committee-hearing-department-navy-fiscal-year-2024-budget-request (accessed September 2, 2023).

[35] U.S. Navy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities–OPNAV N9, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2023, p. 8.

[36] Table 1, “Numbers of Certain Types of Chinese and U.S. Ships Since 2005,” in Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL33153, updated March 9, 2021, pp. 30–31, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/20509332/china-naval-modernization-implications-for-us-navy-capabilities-background-and-issues-for-congress-march-9-2021.pdf (accessed September 2, 2023).

[37] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: May 2021 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, NAICS 336600—Ship and Boat Building,” occupation codes 51-4120, 51-4121, and 51-4122, last modified March 31, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/oes/2021/may/naics4_336600.htm#51-0000 (accessed September 3, 2023), and U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: May 2017 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, NAICS 336600—Ship and Boat Building,” occupation codes 51-4120, 51-4121, and 51-41221, last modified March 30, 2018, https://www.bls.gov/oes/2017/may/naics4_336600.htm (accessed September 3, 2023).

[38] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: May 2022 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, NAICS 336600—Ship and Boat Building,” occupation codes 17-1000–17-3029, last modified April 25, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_336600.htm (accessed September 7, 2023).

[39] The Navy’s FY 2020 30-year shipbuilding plan identified opportunities to build three additional Virginia-class submarines over the next six years and an additional nine next-generation SSNs between FY 2037 and FY 2049. The Navy’s FY 2020 budget requested three Virginia-class SSNs. This was the first time in more than 20 years that the Navy procured three SSNs in one fiscal year. Since the advance procurement for the third Virginia SSN was not included in the Navy’s FY 2019 budget, construction of this third submarine most likely would not have commenced until sometime in FY 2023. Critical parts and equipment for this additional submarine above the planned 10-submarine block buy have not been purchased yet, and the shipyards (Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls Industries Newport News Shipbuilding) have not planned for this submarine as part of their Virginia-class construction.

[40] Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL32418, August 15, 2023, pp. 25–26, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/RL32418.pdf (accessed September 2, 2023).

[41] The Honorable Thomas B. Modly, Acting Secretary of the Navy; Admiral Michael M. Gilday, Chief of Naval Operations; and General David H. Berger, Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, statement on “Fiscal Year 2021 Department of the Navy Budget” before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 5, 2020, pp. 23–24, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Modly--Gilday--Berger_03-05-20.pdf (accessed September 2, 2023).

[42] U.S. Government Accountability Office, Weapon Systems Annual Assessment: Programs Are Not Consistently Implementing Practices That Can Help Accelerate Acquisitions, GAO-23-106059, June 2023, pp. 160 and 165, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-106059.pdf (accessed September 2, 2023).

[43] Transcript, “CNO Gilday at HAC-D Navy Posture Hearing,” U.S. Navy Office of Information, April 29, 2021, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Testimbny/display-testimony/Article/2590426/cno-gilday-at-hac-d-navy-posture-hearing/ (accessed September 2, 2023).

[44] U.S. Government Accountability Office, Weapon Systems Annual Assessment: Programs Are Not Consistently Implementing Practices That Can Help Accelerate Acquisitions, p. 2.

[45] Vice Admiral Robert P. Burke, U.S. Navy, Chief of Naval Personnel and Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Manpower, Personnel, Training & Education), statement on “Personnel Posture of the Armed Services” before the Subcommittee on Personnel, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, February 14, 2018, p. 11, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Burke_02-14-18.pdf (accessed September 2, 2023).