Middle East

Nicole Robinson

The Middle East has long been an important focus of United States foreign and security policy. U.S. security relationships in this strategically important region at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and Africa are built on pragmatism, shared security concerns, and economic interests that include large sales of U.S. arms that enhance the ability of countries in the region to defend themselves. The U.S. also has a long-term interest that derives from the region’s importance as the world’s primary source of oil and gas.

America’s vital national security interests in the Middle East endure but have evolved beyond 1981 when the United States was dependent on Middle East oil. By 2018, the U.S. imported only 11 percent of its oil, the lowest amount since 1957.

The Middle East is a critical component of the global economy. It accounts for 31 percent of global oil production, 18 percent of gas production, 48 percent of proven oil reserves, and 40 percent of proven gas reserves. Approximately 12 percent of global trade and 30 percent of global container traffic traverses the Suez Canal, transporting more than $1 trillion worth of goods each year. In 2018, the Middle East’s daily oil flow constituted approximately 21 percent of global petroleum consumption. Moreover, the region’s significance is not limited to energy. Sixteen of the submarine cables that connect Asia and Europe pass through the Red Sea. While the United States may no longer be dependent on the region’s petrochemical resources, the global economy is.1

The region is home to a wide array of cultures, religions, and ethnic groups: Arabs, Jews, Kurds, Persians, and Turks among others. It also is home to the three Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as well as many smaller religions like the Bahá’í, Druze, Yazidi, and Zoroastrian faiths. The region contains many predominantly Muslim countries as well as the world’s only Jewish state.

The Middle East is deeply sectarian, characterized by long-standing divisions that, exacerbated by religious extremists’ constant vying for power, in some cases are centuries-old. Contemporary conflicts, however, have more to do with modern extremist ideologies and the fact that today’s borders often do not reflect cultural, ethnic, or religious realities. Instead, they are often the results of decisions taken by the British, French, and other powers during and soon after World War I as they dismantled the Ottoman Empire.2

In a way that many in the West do not understand, religion remains a prominent fact of daily life in the modern Middle East, and the friction within Islam between Sunnis and Shias—a friction that dates back to the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD3—is at the heart of many of the region’s conflicts. Sunni Muslims, who form the majority of the world’s Muslim population, hold power in most of the region’s Arab countries.

However, viewing the Middle East’s current instability through the lens of a Sunni–Shia conflict does not reveal the full picture. The cultural and historical division between Arabs and Persians has reinforced the Sunni–Shia split. The mutual distrust between many Sunni Arab powers and Iran, the Persian Shia power, compounded by clashing national and ideological interests, has fueled instability in such countries as Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. Sunni extremist organizations like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) have exploited sectarian and ethnic tensions to gain support by posing as champions of Sunni Arabs against Syria’s Alawite-dominated regime and other non-Sunni governments and movements.

Regional demographic trends also are destabilizing factors. The Middle East’s population is one of the youngest and fastest-growing in the world. This would be viewed as an advantage in most of the West, but not in the Middle East. Known as “youth bulges,” these demographic tsunamis have overwhelmed many countries’ inadequate political, economic, and educational infrastructures, and the lack of access to education, jobs, and meaningful political participation fuels discontent. Because more than half of the region’s inhabitants are less than 30 years old, this demographic bulge will continue to undermine political stability across the region.4

The Middle East has more than half of the world’s oil reserves and is the world’s chief oil-exporting region.5 As the world’s largest producer and consumer of oil,6 the U.S. actually imports relatively little of its oil from the Middle East. Nevertheless, it has a vested interest in maintaining the free flow of oil and gas from the region. Oil is a fungible commodity, and the U.S. economy remains vulnerable to sudden spikes in world oil prices.

During the COVID-19 crisis, oil prices fell temporarily below zero in April 2020 after stay-at-home orders caused a severe imbalance between supply and demand. This unprecedented drop in demand sparked an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, both of which tried to maintain revenue by increasing the price of the reduced amount of oil sold. Although both countries eventually agreed to reduce production by 12 percent, the plummet in oil prices during 2020 caused significant shocks for both exporters and importers.7

U.S. energy policies during 2021 exacerbated the problem. The new Administration’s decisions to shutter some existing energy production and refuse permission for new exploration made the U.S. more sensitive to Middle East–based volatility in the energy market. Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made matters worse. The price of oil jumped to more than $139 a barrel while gas prices doubled—the highest levels for both in almost 14 years.8 In November 2021 and February 2022, Saudi Arabia declined a U.S. request to increase oil production, choosing instead to abide by the April 2020 agreement between the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Russia to cut production.9 Then, in April 2023, OPEC and Russia announced a massive supply cut totaling 1.6 million barrels per day, causing oil prices to jump by $7 a barrel.10

Because many U.S. allies depend on Middle East oil and gas, there is also a second-order effect for the U.S. if supply from the Middle East is reduced or compromised. For example, Japan is the world’s third-largest economy11 and largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG).12 The U.S. might not have to depend on Middle East oil or LNG, but the economic consequences arising from a major disruption of supplies would ripple across the globe. Thus, tensions and instabilities continue to affect global energy markets and directly affect U.S. national security and economic interests.

Beijing knows the Middle East is a vital source of the energy that fuels its economic growth and military. China’s economy and military depend on external resources, which helps to explain why it developed its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to obtain the resources it requires and sustain the routes that connect China to those resources. Imports currently constitute nearly 70 percent of China’s overall oil consumption. Of these imports, 43 percent come from the Gulf region, and China’s oil imports will continue to grow to an estimated 80 percent of its total consumption by 2030.13 It would be a grave strategic error to abandon the Middle East and its petrochemical resources, which sustain the global economy, to Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party.

Financial and logistics hubs are growing along some of the world’s busiest transcontinental trade routes, and one of the region’s economic bright spots in terms of trade and commerce is in the Persian Gulf. The emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), along with Qatar, are competing to become the region’s top financial center.

The economic situation is part of what drives the region’s political environment. The lack of economic freedom helped to fuel the popular discontent that led ultimately to the Arab Spring uprisings, which began in early 2011 and disrupted economic activity, depressed foreign and domestic investment, and slowed economic growth. Sustained financial and economic growth could lead to greater opportunities for the region’s people, but tensions will persist as countries compete for this added wealth.

The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine have had massive repercussions for the entire region, affecting economies and shaking political systems. The World Bank “forecast[s] that the MENA [Middle East and North Africa] region will grow by 3 percent in 2023 and by 3.1 percent in 2024, much lower than the growth rate of 5.8 percent in 2022.”14 Countries that were already facing economic challenges before the pandemic are now facing a long period of recovery during which the likelihood of political instability in an already fragile region can be expected to increase.

The political environment has a direct bearing on how easily the U.S. military can operate in any region of the world. The political situation in many Middle Eastern countries remains fraught with uncertainty. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2010–2012 formed a sandstorm that eroded the foundations of many authoritarian regimes, erased borders, and destabilized many of the region’s countries,15 but the popular uprisings in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen did not usher in a new era of democracy and liberal rule as many in the West were hoping would happen. At best, they made slow progress toward democratic reform; at worst, they added to political instability, exacerbated economic problems, and contributed to the rise of Islamist extremists.

Today, the region’s economic and political outlooks remain bleak. In some cases, self-interested elites have prioritized regime survival over real investment in human capital, aggravating the material deprivation of youth as issues of endemic corruption, high unemployment, and the rising cost of living remain unresolved. Since 2019, large-scale protests have called attention to the region’s lack of economic and political progress. COVID-19 lockdowns and curfews temporarily disrupted protests in Lebanon and Iraq. Demonstrations resumed in 2020 but failed to gain momentum. More recently, the spike in food and gas prices caused in part by the Russian invasion of Ukraine has sparked demonstrations in Iraq and bank robberies in Lebanon16 that, along with ongoing socioeconomic deterioration, have further fueled discontent.17 If similar protests were to break out across the region, they could easily affect the operational environment for U.S. forces.

There is no shortage of security challenges for the U.S. and its allies in this region. Using the breathing space and funding afforded by the July 14, 2015, Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), for example, Iran exploited Shia–Sunni tensions to increase its influence on embattled regimes and undermine adversaries in Sunni-led states. In May 2018, the Trump Administration left the JCPOA after European allies failed to address many of its serious flaws, including its sunset clauses,18 and imposed a crippling economic sanction program in a “maximum pressure campaign” with more than 1,500 sanctions that targeted individuals and entities that were doing business with Iran.19 The sanctions were meant to force changes in Iran’s behavior, particularly with regard to its support for terrorist organizations and refusal to renounce a nascent nuclear weapons program.20

Many of America’s European allies publicly denounced the Trump Administration’s decision to withdraw from the JCPOA, but most officials agree privately that the agreement is flawed and needs to be fixed. America’s allies in the Middle East, including Israel and most Gulf Arab states, supported the U.S. decision and welcomed a harder line against the Iranian regime.21

However, the Biden Administration’s efforts to resurrect the JCPOA threaten to disrupt the gains made by the Trump Administration. On February 18, 2021, the Biden Administration rescinded President Donald Trump’s restoration of U.N. sanctions on Iran, thereby signaling President Joseph Biden’s willingness to negotiate a nuclear agreement with Iran.22 Indirect talks brokered by the European Union between U.S. and Iranian diplomats in Vienna resumed in April 2021.

From the beginning, Iran has been mounting its own maximum-pressure campaign to force President Biden to lift sanctions and return to the 2015 agreement without imposing conditions. The Administration has lifted sanction designations on several entities and individuals several times over the course of the negotiations to inject momentum but with little to show for it.23 Unacceptable Iranian demands for non-nuclear sanctions relief, including the lifting of U.S. terrorist sanctions on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and a guarantee that the International Atomic Energy Agency’s investigation of Iran’s nuclear activities would be ended led to the suspension of negotiations in September 2022.24

Despite Iran’s insistence, the Biden Administration has rightly refused to lift the terrorist designations of the IRGC.25 Anti-regime protests in Iran, sparked by the murder of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini by the morality police, and Iran’s supplying of missiles and drones to Russia have made further negotiations politically difficult.26 Yet the Biden Administration is currently discussing a “freeze-for-freeze” approach to Iran’s nuclear program that would grant partial sanctions relief in exchange for a partial freeze of Iran’s nuclear program.27

Tehran attempts to run an unconventional empire by exerting great influence on sub-state entities like Hamas in the Palestinian territories, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Mahdi movement and other Shia militias in Iraq, and the Houthi insurgents in Yemen. The Iranian Quds Force, the special-operations wing of the IRGC, has orchestrated the formation, arming, training, and operations of these sub-state entities as well as other surrogate militias. These Iran-backed militias have carried out terrorist campaigns against U.S. forces and allies in the region for many years.

On January 2, 2020, President Donald Trump ordered an air strike that killed General Qassem Suleimani, leader of the Iranian Quds Force, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, leader of an Iraqi Shia paramilitary group, both of whom had been responsible for carrying out attacks against U.S. personnel in Iraq. Suleimani’s and Muhandis’s deaths were a huge loss for Iran’s regime and its Iraqi proxies. They also were a major operational and psychological victory for the United States.28 Under the Biden Administration, attacks by Iran’s proxies against U.S. forces in the region have increased dramatically. Since President Biden took office, Iranian proxies have carried out drone and rocket attacks against U.S. troops in the region 83 times according to U.S. Central Command. Washington has responded with force only four times.29

In Afghanistan, Tehran’s influence on some Shiite groups is such that thousands have volunteered to join IRGC-led militias deployed to fight for Bashar al-Assad in Syria.30 Iran also provided arms to the Taliban after it was ousted from power by a U.S.-led coalition31 and has long considered the Afghan city of Herat near the Afghanistan–Iran border to be within its sphere of influence. The Biden Administration’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan paved the way for a Taliban takeover and a deepening of ties between Tehran and Kabul, increasing Iran’s growing influence in the region.

Iran already looms large over its weak and divided Arab rivals. Iraq and Syria have been destabilized by insurgencies and civil war and may never fully recover, Egypt is distracted by its own internal economic problems, and Jordan has been inundated by a flood of Syrian refugees and is threatened by the instability in Syria.32 Meanwhile, Tehran has continued to build up its missile arsenal, which is the largest in the Middle East; has continued its efforts to prop up the Assad regime in Syria; and supports Shiite Islamist revolutionaries across the region.33

To raise funds for its regional proxies, Iran works with rogue actors in Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria to traffic drugs like Captagon, a psychostimulant that has become the most in-demand narcotic in the region. The more than $10 billion Captagon trade bankrolls the Bashar al-Assad dictatorship in Syria, Lebanese Hezbollah, and Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq and has sparked a regional drug war that especially affects Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and other countries in the Persian Gulf.34 If violence were to break out among rival drug cartels, the effects on the operational environment for U.S. forces could be significant.

Tehran’s main partner in the drug trade is Syria’s Bashar al-Assad regime, whose brutal repression of peaceful demonstrations early in 2011 ignited a fierce civil war that killed more than half a million people and created a major humanitarian crisis: according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “15.3 million people in need of humanitarian and protection assistance in Syria”; “5.3 million Syrian refugees worldwide, of whom 5.5 million hosted in countries near Syria” like Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan; and “6.8 million internally displaced persons” within Syria.35 The large refugee populations created by this civil war could become a source of recruits for extremist groups. For example, both the Islamist Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, formerly known as the al-Qaeda–affiliated Jabhat Fateh al-Sham and before that as the al-Nusra Front, and the self-styled Islamic State (IS), formerly known as ISIS or ISIL and before that as al-Qaeda in Iraq, used the power vacuum created by the war to carve out extensive sanctuaries where they built proto-states and trained militants from a wide variety of other Arab countries, Central Asia, Russia, Europe, Australia, and the United States.36 At the height of its power, with a sophisticated Internet and social media presence and by capitalizing on the civil war in Syria and sectarian divisions in Iraq, the IS was able to recruit more than 25,000 fighters from outside the region to join its ranks in Iraq and Syria. These foreign fighters included thousands from Western countries, among them the United States.

In 2014, the U.S. announced the formation of a broad international coalition to defeat the Islamic State. By early 2019, the territorial “caliphate” had been destroyed by a U.S.-led coalition of international partners. However, the socioeconomic meltdown of Lebanon and ongoing fighting in Syria present the ideal environment for the IS to reconstitute itself. Multiple reports indicate that the IS is recruiting young men in Tripoli, Lebanon.37 There is a real danger that IS or other Islamic extremists could capitalize on the security vacuum created by that country’s ongoing deterioration.38 The fall of Afghanistan has also opened the door for a revival of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Rebuilding the group will take time, but al-Qaeda remains a long-term threat to American interests and citizens as well as to the homeland.39

Arab–Israeli tensions are another source of regional instability. The repeated breakdown of Israeli–Palestinian peace negotiations has created an even more antagonistic situation. Hamas, the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood that has controlled Gaza since 2007, seeks to transform the conflict from a national struggle over sovereignty and territory into a religious conflict in which compromise is denounced as blasphemy. Hamas invokes jihad in its struggle against Israel and seeks to destroy the Jewish state and replace it with an Islamic state.

The signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020 caused a brief spark of hope. These U.S.-brokered agreements normalizing relations between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan have created new opportunities for trade, investment, and defense cooperation.40 To strengthen the Abraham Accords, the U.S., Egypt, the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Israel established the Negev Forum, a new framework for cooperation in the region with six working groups: Clean Energy, Education and Coexistence, Food and Water Security, Health, Regional Security, and Tourism.41 These efforts are important milestones in the diplomatic march toward a broader Arab–Israeli peace.42

However, Israeli–Palestinian tensions have worsened over the past three years. In both April 2021 and 2022, Hamas fired a barrage of rockets into Israel from Gaza following deadly violence and attacks in Jerusalem’s Old City. Israel responded with air strikes.43 In 2023, tensions took on a new dimension after days of escalating violence in Jerusalem led to rockets being fired not only by Hamas in Gaza, but also by the Al-Quds Brigades, an armed wing of the Syria-based Palestinian Islamic Jihad.44 Increased violence threatens the stability of Israel at a time of increased internal division. In March 2023, tens of thousands of Israelis took to the streets to protest judicial reforms proposed by the Netanyahu government.45 As this book was being prepared, the situation remained tense.

Important Alliances and Bilateral Relations in the Middle East

The U.S. has strong military, security, intelligence, and diplomatic ties with several Middle Eastern nations, including Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Because the historical and political circumstances that led to the creation of NATO have been largely absent in the Middle East, the region lacks a similarly strong collective security organization.

In 2017, the Trump Administration proposed the idea of a multilateral Middle East Strategic Alliance with its Arab partners.46 The initial U.S. concept, which included security, economic cooperation, and conflict resolution and deconfliction, generated considerable enthusiasm, but the project has since been sidelined although discussions are ongoing in Congress with a view to creating some sort of “regional security architecture” within the Abraham Accords framework.47

In April 2022, shortly after the March 2022 Negev summit, the U.S. established the 34-nation Combined Task Force 153 “to enhance international maritime security and capacity-building efforts in the Red Sea, Bab al-Mandeb and Gulf of Aden.”48 Over the spring and summer of 2022, the U.S. organized regional discussions about air-defense cooperation.49 To build on these agreements, the U.S. will host Negev Forum partners for defense meetings in 2023 that will focus on capacity-building and the sharing of best practices on such issues as border security, disaster preparedness, and climate change. Traditionally, however, Middle Eastern countries have preferred to maintain bilateral relationships with the U.S. and generally have shunned multilateral arrangements because of the lack of trust among Arab states.

This lack of trust manifested itself in June 2017 when the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt, and several other Muslim-majority countries cut or downgraded diplomatic ties with Qatar after Doha was accused of supporting terrorism in the region.50 These nations severed all commercial land, air, and sea travel with Qatar and expelled Qatari diplomats and citizens. In January 2021, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt agreed to restore ties with Qatar during the 41st Gulf Cooperation Council summit. Per the agreement, Saudi Arabia and its GCC allies lifted the economic and diplomatic blockade of Qatar, reopening their airspace, land, and sea borders. This diplomatic détente paves the way for full reconciliation in the GCC and, at least potentially, a more united front in the Gulf.51

Military training is an important part of these relationships. Exercises involving the United States are intended principally to ensure close and effective coordination with key regional partners, demonstrate an enduring U.S. security commitment to regional allies, and train Arab armed forces so that they can assume a larger share of responsibility for regional security.

Israel. America’s most important bilateral relationship in the Middle East is with Israel. Both countries are democracies, value free-market economies, and believe in human rights at a time when many Middle Eastern countries reject those values. With support from the United States, Israel has developed one of the world’s most sophisticated air and missile defense networks.52 No significant progress on peace negotiations with the Palestinians or on stabilizing Israel’s volatile neighborhood is possible without a strong and effective Israeli–American partnership.

Ties between the U.S. and Israel improved significantly during the Trump Administration, encouraged by the relocation of America’s embassy from Tel Aviv to western Jerusalem in 2018 and the Administration’s role in facilitating the Abraham Accords, which were signed in 2020, and so far have shown no signs of deteriorating under the Biden Administration.53 Officials have stated, however, that the Abraham Accords are not a substitute for Israeli–Palestinian peace. At the same time, the Biden Administration has shown little interest in taking an active role in Israeli–Palestinian peace negotiations, explaining instead that it will promote equal rights for Palestinians and Israelis rather than focusing on resolving the overarching dispute.54 If the conflict between the two sides continues to escalate, President Biden may find himself pressured to become more involved.

Saudi Arabia. After Israel, the deepest U.S. military relationship is with the Gulf States, including Saudi Arabia, which serves as de facto leader of the Gulf Cooperation Council. America’s relationship with Saudi Arabia is based on pragmatism and is important for both security and economic reasons, but it has come under intense strain since the October 2018 murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey.

The Saudis enjoy huge influence across the Muslim world, and approximately 2 million Muslims participate in the annual Hajj pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca. Riyadh has been a key partner in efforts to counter the influence of Iran. The U.S. is also the largest provider of arms to Saudi Arabia and regularly, if not controversially, sells munitions needed to resupply stockpiles expended in the Saudi-led campaign against the Houthis in Yemen.

Under the Biden Administration, bilateral relations have significantly deteriorated because the Administration turned a blind eye to Houthi aggression. For example, the Biden Administration lifted the Trump Administration’s designation of the Houthi Ansar Allah (Supporters of God) movement as a terrorist organization despite Houthi drone and ballistic missile attacks against military and civilian targets in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have called for a redesignation of the Houthis, but as this book was being prepared, no such designation had been imposed.55 The bilateral relationship has deteriorated further over oil production disputes. After OPEC+ decided to cut oil production,56 the Biden Administration vowed that there would be “consequences” for Saudi Arabia. The Administration has failed to follow through on this threat, which has further strained the relationship between the two countries.

Gulf Cooperation Council. The GCC’s member countries are located in an oil-rich region close to the Arab–Persian fault line and are therefore strategically important to the U.S.57 The root of Arab–Iranian tensions in the Gulf is Iran’s ideological drive to export its Islamist revolution and overthrow the traditional rulers of the Arab kingdoms. This ideological clash has further amplified long-standing sectarian tensions between Shia Islam and Sunni Islam. Tehran has sought to radicalize Shia Arab minority groups to undermine Sunni Arab regimes in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Yemen, and Bahrain. It also sought to incite revolts by the Shia majorities in Iraq against Saddam Hussein’s regime and in Bahrain against the Sunni al-Khalifa dynasty. Culturally, many Iranians look down on the Gulf States, many of which they see as artificial entities carved out of the former Persian Empire and propped up by Western powers.

GCC member countries often have difficulty agreeing on a common policy with respect to matters of security. This reflects both the organization’s intergovernmental nature and its members’ desire to place national interests above those of the GCC. The 2017 dispute regarding Qatar illustrates this difficulty.

Another source of disagreement involves the question of how best to deal with Iran. The UAE, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, all of which once opposed the Iran nuclear deal, have restored diplomatic relations with Tehran, the UAE and Kuwait in 2022 and Saudi Arabia in a deal brokered by China in March 2023.58 Bahrain still maintains a hawkish view of the threat from Iran. Oman prides itself on its regional neutrality, and Qatar shares natural gas fields with Iran, so it is perhaps not surprising that both countries view Iran’s activities in the region as less of a threat and maintain cordial relations with Tehran.

Egypt. Egypt is another important U.S. military ally. As one of six Arab countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Israel (the others are Jordan, Bahrain, the UAE, Sudan, and Morocco), Egypt is closely enmeshed in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and remains a leading political, diplomatic, and military power in the region.

Relations between the U.S. and Egypt have been difficult since the downfall of President Hosni Mubarak in 2011 after 30 years in power. The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi was elected president in 2012 and used the Islamist-dominated parliament to pass a constitution that advanced an Islamist agenda. Morsi’s authoritarian rule, combined with rising popular dissatisfaction with falling living standards, rampant crime, and high unemployment, led to a massive wave of protests in June 2013 that prompted a military coup in July. The leader of the coup, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, pledged to restore democracy and was elected president in 2014 and again in 2018 in elections that many considered to be neither free nor fair.

Sisi’s government faces major political, economic, and security challenges. However, because of Egypt’s ban on anti-government demonstrations and Sisi’s tight control of internal security, there was only one outbreak of protests in 2018.59 Internal security may deteriorate if historically high rates of inflation and bread prices continue to rise—a development that could trigger a new wave of anti-government protests—or if the Islamic State resurges inside Egypt.60

Quality of Armed Forces in the Region

The quality and capabilities of the region’s armed forces are mixed. Some countries spend billions of dollars each year on advanced Western military hardware; others spend very little. Saudi Arabia’s military budget is by far the region’s largest, but in 2021 (the most recent year for which data are available), Oman spent the region’s highest percentage of GDP on defense at 7.3 percent, followed by Kuwait at 6.7 percent. Saudi Arabia dropped down to third in the region at 6.6 percent. Qatar (based on data released for the first time since 2010) spent 4.8 percent of its GDP on defense.61

Different security factors drive the degree to which Middle Eastern countries fund, train, and arm their militaries. For Israel, which fought and defeated Arab coalitions in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982, the chief potential threat to its existence is now an Iranian regime that has called for Israel to be “wiped off the map.”62 States and non-state actors in the region have invested in asymmetric and unconventional capabilities to offset Israel’s military superiority.63 For the Gulf States, the main driver of defense policy is the Iranian military threat combined with internal security challenges; for Iraq, it is the internal threat posed by Iran-backed militias and Islamic State terrorists.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) are considered the most capable military forces in the Middle East. Iran and other Arab countries have spent billions of dollars in an effort to catch up with Israel, but U.S. support preserves Israel’s qualitative military edge (QME). Iran is steadily improving its missile capabilities and, due to the expiration of the U.N. conventional arms embargo in October 2020, now has access to the global arms trade.64 In response, Arab countries are upgrading their weapons capabilities while establishing officer training programs to improve military effectiveness.65

Israel funds its military sector heavily and has a strong national industrial capacity that is supported by significant funding from the U.S. Combined, these factors give Israel a regional advantage despite limitations of manpower and size. In particular, the IDF has focused on maintaining its superiority in missile defense, intelligence collection, precision weapons, and cyber technologies.66 The Israelis regard their cyber capabilities as especially important and use cyber technologies for a number of purposes that include defending Israeli cyberspace, gathering intelligence, and carrying out attacks.67

In 2010, Israel signed a $2.7 billion deal with the U.S. to acquire approximately 20 F-35I Adir Lightning fighter jets (the F-35I is a heavily modified version of the Lockheed Martin F-35 stealth fighter).68 In the 2021 conflict with Hamas, these jets were deployed in a major combat operation that targeted dozens of Hamas rocket launch tubes in northern Gaza.69 In December 2021, Israel also signed a $3 billion deal with the U.S. to buy 12 Lockheed Martin–Sikorsky CH-53K helicopters and two Boeing KC-46 refueling planes to replace the Sikorsky CH-53 Yas’ur heavy-lift aircraft that have been in use since the late 1960s. These aircraft would aid Israel in the event of conflict with Iran.70

Israel maintains its qualitative superiority in medium-range and long-range missile capabilities and fields effective missile defense systems, including Iron Dome, Arrow, and David’s Sling, all of which have benefitted from U.S. financing and technical support.71 Israel also has a nuclear weapons capability (which it does not publicly acknowledge) that increases its strength relative to other powers in the region and has helped to deter adversaries as the gap in conventional capabilities has been reduced.

After Israel, the most technologically advanced and best-equipped armed forces are found in the GCC countries. Previously, the export of oil and gas meant that there was no shortage of resources to devote to defense spending, but the up-and-down nature of oil prices in recent years may force oil-exporting countries to adjust their defense spending patterns. Nevertheless, GCC nations still have the region’s best-funded (even if not necessarily its most effective) Arab armed forces. All GCC members boast advanced defense hardware that reflects a preference for U.S., United Kingdom (U.K.), and French equipment.

The GCC’s most capable military force is Saudi Arabia’s: an army of 75,000 soldiers and a National Guard of 130,000 personnel reporting directly to the king. Its army operates 1,010 main battle tanks including 500 U.S.-made M1A2s. Its air force is built around American-built and British-built aircraft and consists of more than 455 combat-capable aircraft that include F-15s, Tornados, and Typhoons.72

Air power is the strong suit of most GCC members. Oman, for example, operates F-16s and Typhoons. In 2018, the U.S. government awarded Lockheed Martin a $1.12 billion contract to produce 16 new F-16 Block 70 aircraft (Lockheed Martin’s newest and most advanced F-16 production configuration) for the Royal Bahraini Air Force. Bahrain is expected to receive its first batch of upgraded aircraft in 2024.73 Qatar operates French-made Mirage fighters and has purchased at least 24 Typhoons from the U.K.74

In November 2020, the U.S. Department of State notified Congress that it had approved the sale of a $23.4 billion defense package of F-35A Joint Strike Fighters, armed drones, munitions, and associated equipment to the UAE.75 After a temporary freeze on arms sales by the Biden Administration, the sale moved forward in April 2021. The sale is somewhat controversial because of Israeli concerns about other regional powers also possessing the most modern combat aircraft and potentially challenging an important Israeli advantage.

Middle Eastern countries have shown a willingness to use their military capabilities under certain limited circumstances. The navies of GCC member countries rarely deploy beyond their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), but Kuwait, Bahrain, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have participated in and, in some cases, have commanded Combined Task Force 152, formed in 2004 to maintain maritime security in the Persian Gulf.76 Egypt commands Combined Task Force 153, a 34-nation naval partnership established in 2022, as noted previously, “to enhance international maritime security and capacity-building efforts in the Red Sea, Bab Al-Mandeb and Gulf of Aden.”77 In 2011, the UAE and Qatar deployed fighters to participate in NATO-led operations over Libya, although they did not participate in strike operations. To varying degrees, all six GCC members also joined the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition with the UAE contributing the most in terms of air power.78 Air strikes in Syria by members of the GCC ended in 2017.

With 438,500 active personnel and 479,000 reserve personnel, Egypt has the region’s largest Arab military force.79 It possesses a fully operational military with an army, air force, air defense, navy, and special operations forces. Until 1979, when the U.S. began to supply Egypt with military equipment, Cairo relied primarily on less capable Soviet military technology.80 Since then, its army and air force have been significantly upgraded with U.S. military weapons, equipment, and warplanes. Egypt’s naval capabilities have also grown with the opening of a naval base at Ras Gargoub and the commissioning of a fourth Type-209/1400 submarine and a second FREMM frigate.81

Egypt has struggled with increased terrorist activity in the Sinai Peninsula, including attacks on Egyptian soldiers and foreign tourists and the October 2015 bombing of a Russian airliner departing from the Sinai. The Islamic State’s Sinai Province terrorist group has claimed responsibility for all of these actions.82 Although the Egyptian army regained control of two IS-controlled villages, militant attacks against army affiliates in different parts of North Sinai and the kidnapping of tribal leaders threaten the stability of the area.83

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a close U.S. ally, and its military forces, while small, are effective. The principal threats to Jordan’s security include terrorism, political turbulence, refugees, and the trade in Captagon spilling over from Syria and Iraq. Although Jordan faces few conventional threats from its neighbors, its internal security is threatened by Islamist extremists who have fought in the region and have been emboldened by the growing influence of al-Qaeda and other Islamist militants. As a result, Jordan’s highly professional armed forces have had to focus on border and internal security in recent years.

Considering Jordan’s size, its conventional capability is significant. Jordan’s ground forces total 86,000 soldiers and include 182 British-made Challenger 1 tanks and several French-made Leclerc tanks. Two squadrons of F-16 Fighting Falcons form the backbone of its air force,84 and its special operations forces are highly capable, having benefitted from extensive U.S. and U.K. training. Jordanian forces have served in Afghanistan and in numerous U.N.-led peacekeeping operations.

Iraq has fielded one of the region’s most dysfunctional military forces. After the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011, Iraq’s government selected and promoted military leaders according to political criteria.85 Shiite army officers were favored over their Sunni, Christian, and Kurdish counterparts, and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki chose top officers according to their political loyalties. Politicization of the armed forces also encouraged corruption within many units with some commanders siphoning off funds allocated for “ghost soldiers” who never existed or had been separated from the army for various reasons.86

The promotion of incompetent military leaders, poor logistical support because of corruption and other problems, limited operational mobility, and weaknesses in intelligence, reconnaissance, medical support, and air force capabilities have combined to undermine the effectiveness of Iraq’s armed forces. In June 2014, for example, the collapse of as many as four divisions that were routed by vastly smaller numbers of Islamic State fighters led to the fall of Mosul.87 The U.S. and its allies responded with a massive training program for the Iraqi military that led to the liberation of Mosul on July 9, 2017.88

Since 2017, the capabilities and morale of Iraq’s armed forces have improved, but there is still concern about Baghdad’s ability to sustain operational effectiveness in the face of the current U.S. drawdown and redeployment of forces. The continued presence of armed militias presents the biggest obstacle to force unity.89

Current U.S. Military Presence in the Middle East

Before 1980, the limited U.S. military presence in the Middle East consisted chiefly of a small naval force that had been based in Bahrain since 1958. The U.S. “twin pillar” strategy relied on prerevolutionary Iran and Saudi Arabia to take the lead in defending the Persian Gulf from the Soviet Union and its client regimes in Iraq, Syria, and South Yemen,90 but the 1979 Iranian revolution demolished one pillar, and the December 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan increased the Soviet threat to the Gulf.

In January 1980, President Jimmy Carter proclaimed in a commitment known as the Carter Doctrine that the United States would take military action to defend oil-rich Persian Gulf States from external aggression. In 1980, he ordered the creation of the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF), the precursor to U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM), which was established in January 1983.91

Until the late 1980s, according to USCENTCOM, America’s “regional strategy still largely focused on the potential threat of a massive Soviet invasion of Iran.”92 After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime became the chief threat to regional stability. Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, and the United States responded in January 1991 by leading an international coalition of more than 30 nations to expel Saddam’s forces from Kuwait. CENTCOM commanded the U.S. contribution of more than 532,000 military personnel to the coalition’s armed forces, which totaled at least 737,000.93 This marked the peak U.S. force deployment in the Middle East.

Confrontations with Iraq continued throughout the 1990s as Iraq continued to violate the 1991 Gulf War cease-fire. Baghdad’s failure to cooperate with U.N. arms inspectors to verify the destruction of its weapons of mass destruction and its links to terrorism led to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. During the initial invasion, U.S. forces numbered nearly 192,000,94 joined by military personnel from coalition forces. Apart from the “surge” in 2007, when President George W. Bush deployed an additional 30,000 personnel, the number of American combat forces in Iraq fluctuated between 100,000 and 150,000.95

In December 2011, the U.S. officially completed its withdrawal of troops, leaving only 150 personnel attached to the U.S. embassy in Iraq.96 Later, in the aftermath of IS territorial gains in Iraq, the U.S. redeployed thousands of troops to the country to assist Iraqi forces against IS and help to build Iraqi capabilities.

In 2021, the Biden Administration brought America’s combat mission in Iraq to a close and transitioned U.S. forces involvement to an advisory role. U.S. force levels in Iraq declined from 5,200 in 2020 to 2,500 in January 2021.97 CENTCOM Commander General Frank McKenzie stated that “[a]s we look into the future, any force level adjustment in Iraq is going to be made as a result of consultations with the government of Iraq.”98

The U.S. continues to maintain a limited number of forces in other locations in the Middle East, primarily in GCC countries. Rising naval tensions in the Persian Gulf prompted the additional deployments of troops, Patriot missile batteries, and combat aircraft to the Gulf in late 2019 to deter Iran, but most were later withdrawn.99 In August 2022, it was reported that the U.S. State Department had “approved more than $5 billion in arms deals for key Middle East partners, including $3.05 billion in Patriot missiles for Saudi Arabia” to defend itself “against persistent Houthi cross-border unmanned aerial system and ballistic missile attacks on civilian sites and critical infrastructure” and “$2.25 billion in THAAD [Terminal High Altitude Area Defense] systems for the United Arab Emirates.”100

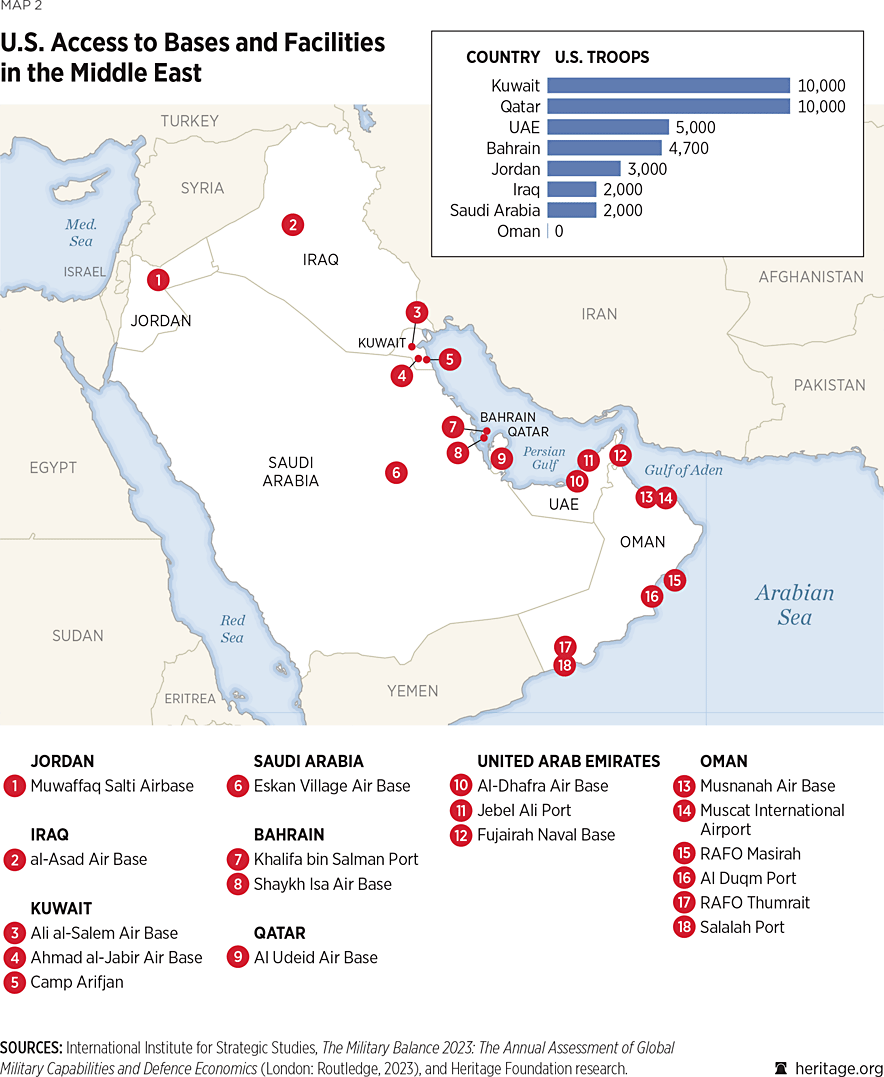

By January 2022, CENTCOM had deployed an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 U.S. troops in 21 countries within its area of responsibility.101 Although the exact disposition of U.S. forces is hard to triangulate because of the fluctuating nature of U.S. military operations in the region,102 information gleaned from open sources reveals the following:

- Kuwait. More than 13,500 U.S. personnel are based in Kuwait and spread among Camp Arifjan, Ahmad al-Jabir Air Base, and Ali al-Salem Air Base. A large depot of prepositioned equipment and a squadron of fighters and Patriot missile systems are also deployed to Kuwait.103

- United Arab Emirates. About 3,500 U.S. personnel are deployed at Jebel Ali port, Al Dhafra Air Base, and naval facilities at Fujairah. Jebel Ali port is the U.S. Navy’s busiest port of call for aircraft carriers. U.S. Air Force personnel who are stationed in the UAE use Al Dhafra Air Base to operate fighters, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), refueling aircraft, and surveillance aircraft. In addition, the United States has regularly deployed F-22 Raptor combat aircraft to Al Dhafra and in April 2021 deployed the F-35 combat aircraft because of escalating tensions with Iran. Patriot and THAAD missile systems are deployed for air and missile defense.104

- Oman. In 1980, Oman became the first Gulf State to welcome a U.S. military base. Today, it provides important access in the form of over 5,000 aircraft overflights, 600 aircraft landings, and 80 port calls annually. The number of U.S. military personnel in Oman has fallen to a few hundred, mostly from the U.S. Air Force. According to the Congressional Research Service, a March 2019 U.S.–Oman Strategic Framework Agreement “expand[ed] the U.S.–Oman facilities access agreements by allowing U.S. forces to use the ports of Al Duqm, which is large enough to handle U.S. aircraft carriers, and Salalah.” In addition, “Oman is trying to expand and modernize its arsenal primarily with purchases from the United States. As of June 2021, the United States ha[d] 72 active cases valued at $2.7 billion with Oman under the government-to-government Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system.”105

- Bahrain. More than 9,000 U.S. military personnel are based in Bahrain. Because Bahrain is home to Naval Support Activity Bahrain and the U.S. Fifth Fleet, most U.S. military personnel there belong to the U.S. Navy. A significant number of U.S. Air Force personnel operate out of Shaykh Isa Air Base, where F-16s, F/A-18s, and P-8 surveillance aircraft are stationed. U.S. Patriot missile systems also are deployed to Bahrain. The deep-water port of Khalifa bin Salman is one of the few facilities in the Gulf that can accommodate U.S. aircraft carriers. In 2021, Bahrain became an operational hub for the use of new artificial intelligence technology to direct Unmanned Surface Vessels and unmanned underwater vehicles in the CENTCOM area of responsibility.106

- Saudi Arabia. In June 2021, President Biden reported to Congress that approximately 2,700 U.S. military personnel were deployed in Saudi Arabia “to protect United States forces and interests in the region against hostile action by Iran or Iran-backed groups.” The President confirmed that these troops, “operating in coordination with the Government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, provide air and missile defense capabilities and support the operation of United States fighter aircraft.”107 The six-decade-old United States Military Training Mission to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the four-decade-old Office of the Program Manager of the Saudi Arabian National Guard Modernization Program, and the Office of the Program Manager–Facilities Security Force are based in Eskan Village Air Base approximately 13 miles south of the capital city of Riyadh.108

- Qatar. The number of U.S. personnel, mainly from the U.S. Air Force, deployed in Qatar “has ranged from about 8,000 to over 10,000.”109 The U.S. operates its Combined Air Operations Center at Al Udeid Air Base, which is one of the world’s most important U.S. air bases. It is also the base from which the anti-ISIS campaign was headquartered. Heavy bombers, tankers, transports, and ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) aircraft operate from Al Udeid Air Base, which also serves as the forward headquarters of CENTCOM. The base houses prepositioned U.S. military equipment and is defended by U.S. Patriot missile systems. The recent tensions between Qatar and other Arab states have not affected the United States’ relationship with Qatar.

- Jordan. According to CENTCOM, “the Jordanian Armed Forces is one of [America’s] strongest and most reliable partners in the Levant sub-region.”110 Although there are no U.S. military bases in Jordan, the U.S. has a long history of conducting training exercises out of Jordanian air bases. The Congressional Research Service has reported that “Jordanian air bases have been particularly important for the U.S. conduct of intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions in Syria and Iraq” and that “[a]s of June 2022…approximately 2,833 United States military personnel [were] deployed to Jordan to counter the Islamic State and enhance Jordan’s security.”111 In addition:

- Beyond the need to use Jordanian facilities to counter the Islamic State throughout the region, CENTCOM may seek to partner more closely with Jordan in order to position U.S. materiel to counter Iran. In summer 2021, the U.S. Department of Defense announced that equipment and materiel previously stored at a now-closed U.S. base in Qatar would be moved to Jordan.112

CENTCOM “directs and enables military operations and activities with allies and partners to increase regional security and stability in support of enduring U.S. interests.”113 Execution of this mission is supported by four service component commands (U.S. Naval Forces Middle East [USNAVCENT]; U.S. Army Forces Middle East [USARCENT]; U.S. Air Forces Middle East [USAFCENT]; and U.S. Marine Forces Middle East [MARCENT]) and one subordinate unified command (U.S. Special Operations Command Middle East [SOCCENT]).

- U.S. Naval Forces Central Command. USNAVCENT is USCENTCOM’s maritime component. With its forward headquarters in Bahrain, it is responsible for commanding the afloat units that rotationally deploy or surge from the United States in addition to other ships that are based in the Gulf for longer periods. USNAVCENT conducts persistent maritime operations to advance U.S. interests, deter and counter disruptive countries, defeat violent extremism, and strengthen partner nations’ maritime capabilities in order to promote a secure maritime environment in an area that encompasses approximately 2.5 million square miles of water.

- U.S. Army Forces Central Command. USARCENT is USCENTCOM’s land component. Based in Kuwait, it is responsible for land operations in an area that totals 4.6 million square miles (1.5 times larger than the continental United States).

- U.S. Air Forces Central Command. USAFCENT is USCENTCOM’s air component. Based in Qatar, it is responsible for air operations and for working with the air forces of partner countries in the region. It also manages an extensive supply and equipment prepositioning program at several regional sites.

- U.S. Marine Forces Central Command. MARCENT is USCENTCOM’s designated Marine Corps service component. Based in Bahrain, it is responsible for all Marine Corps forces in the region.

- U.S. Special Operations Command Central. SOCCENT is a subordinate unified command under USCENTCOM. Based in Qatar, it is responsible for planning special operations throughout the USCENTCOM region, planning and conducting peacetime joint/combined special operations training exercises, and orchestrating command and control of peacetime and wartime special operations.

In addition to the American military presence in the region, two NATO allies—the United Kingdom and France—play an important role.

The U.K.’s presence in the Middle East is a legacy of British imperial rule. The U.K. has maintained close ties with many countries that it once ruled and has conducted military operations in the region for decades. As of 2020, approximately 1,350 British service personnel were based throughout the region.114 This number fluctuates with the arrival of visiting warships.

The British presence in the region is dominated by the Royal Navy. Permanently based naval assets include four mine hunters and one Royal Fleet Auxiliary supply ship. In addition, there generally are frigates or destroyers in the Gulf or Arabian Sea performing maritime security duties,115 and (although such matters are not the subject of public discussion) U.K. attack submarines also operate in the area. In April 2018, as a sign of its long-term maritime presence in the region, the U.K. opened a base in Bahrain—its first overseas military base in the Middle East in more than four decades.116 The U.K. has made a multimillion-dollar investment in modernization of the Duqm Port complex in Oman to accommodate its new Queen Elizabeth–class aircraft carriers.117

The U.K. also has a small Royal Air Force (RAF) presence in the region, mainly in the UAE and Oman. A short drive from Dubai, Al-Minhad Air Base is home to a small contingent of U.K. personnel, and small RAF detachments in Oman support U.K. and coalition operations in the region. Although considered to be in Europe, the U.K.’s Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia in Cyprus have supported U.S. military and intelligence operations in the past and are expected to continue to do so.

Moreover, the British presence in the region is not limited to soldiers, ships, and planes. A British-run staff college operates in Qatar, and Kuwait chose the U.K. to help run its own equivalent of the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.118 The U.K. also plays a very active role in training the Saudi Arabian and Jordanian militaries.

The French presence in the Gulf is smaller than the U.K.’s but still significant. France opened its first military base in the Gulf in 2009. Located in the emirate of Abu Dhabi, it was the first foreign military installation built by the French in 50 years.119 The French have 700 personnel based in the UAE along with seven Rafale jets and an armored battlegroup, as well as military operations in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.120 French ships have access to the Zayed Port in Abu Dhabi, which is big enough to handle every ship in the French Navy except the aircraft carrier Charles De Gaulle.

Military support from the U.K. and France has been particularly important in Operation Inherent Resolve, a U.S.-led joint task force that was formed to combat the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. As of May 2021, France had between 600 and 650 troops stationed in the UAE; 600 stationed in Jordan, Syria, and Iraq; and 650 stationed in Lebanon.121 The U.K. temporarily redeployed troops back to the U.K. because of COVID-19 but announced in February 2021 that 500 troops would be sent back along with an additional 3,500 troops to boost its counterterrorism training mission in Iraq.122 The additional troops will help both to prevent the IS from returning and to manage threats from Iran-backed militias more effectively.

Another important actor in Middle East security is the small East African country of Djibouti. Djibouti sits on the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, through which an estimated 6.2 million barrels of oil a day transited in 2018 (the most recent year for which U.S. Energy Administration data are available) and which is a choke point on the route to the Suez Canal.123 An increasing number of countries recognize Djibouti’s value as a base from which to project maritime power and launch counterterrorism operations. The country is home to Camp Lemonnier, which can hold as many as 4,000 personnel and is the only permanent U.S. military base in Africa.124

China is also involved in Djibouti and has established its first permanent overseas base there. This base can house 10,000 troops, and Chinese marines have used it to stage live-fire exercises featuring armored combat vehicles and artillery. France, Italy, and Japan also have presences of varying strength in Djibouti.125

Key Infrastructure and Warfighting Capabilities

The Middle East is critically situated geographically. Two-thirds of the world’s population lives within an eight-hour flight from the Gulf region, making it accessible from most other regions of the globe. The Middle East also contains some of the world’s most critical maritime choke points, including the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz.

Although infrastructure is not as developed in the Middle East as it is in North America or Europe, during a decades-long presence, the U.S. has developed systems that enable it to move large numbers of matériel and personnel into and out of the region. According to the Department of Defense, at the height of U.S. combat operations in Iraq during the Second Gulf War, the U.S. presence included 165,000 servicemembers and 505 bases. Moving personnel and equipment out of the country was “the largest logistical drawdown since World War II” and included redeployment of “the 60,000 troops who remained in Iraq at the time and more than 1 million pieces of equipment ahead of their deadline.”126

The condition of the region’s roads varies from country to country. All of the roads in Israel, Jordan, and the UAE are paved. Other nations—for example, Oman (60,230 km); Saudi Arabia (221,372 km); and Yemen (71,300 km)—have poor paved road coverage.127 Rail coverage is also poor. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has targeted ports, roads, and railway development in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and many other countries, and the result could be improved transportation conditions across the region at the expense of U.S. interests.128

The U.S. has access to several airfields in the region. The primary air hub for U.S. forces is Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. Other airfields include Ali Al Salem Air Base in Kuwait; Al Dhafra and Al Minhad in the UAE; Isa in Bahrain; Eskan Village Air Base in Saudi Arabia; and Muscat, Thumrait, Masirah Island, and the commercial airport at Seeb in Oman. In the past, the U.S. has used major airfields in Iraq, including Baghdad International Airport and Balad Air Base, as well as Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia.

The fact that a particular air base is available to the U.S. today, however, does not necessarily mean that it will be available for a particular operation in the future. For example, because of their more cordial relations with Iran, Qatar and Oman probably would not allow the U.S. to use air bases in their territory for strikes against Iran unless they were first attacked themselves.

The U.S. also has access to ports in the region, the most important of which may be the deep-water port of Khalifa bin Salman in Bahrain and naval facilities at Fujairah in the UAE.129 The UAE’s commercial port of Jebel Ali is open for visits from U.S. warships and the prepositioning of equipment for operations in theater.130

In March 2019, “Oman and the United States signed a ‘Strategic Framework Agreement’ that expands the U.S.–Oman facilities access agreements by allowing U.S. forces to use the ports of Al Duqm, which is large enough to handle U.S. aircraft carriers, and Salalah.”131 The location of these ports outside the Strait of Hormuz makes them particularly useful. Approximately 90 percent of the world’s trade travels by sea, and some of the busiest and most important shipping lanes are located in the Middle East. Tens of thousands of cargo ships travel through the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait each year.

Given the high volume of maritime traffic in the region, no U.S. military operation can be undertaken without consideration of the opportunity and risk that these shipping lanes offer to America and her allies. The major shipping routes include:

- The Suez Canal. In 2022, more than 22,000 ships transited the Suez Canal—an average of 60 ships per day.132 Considering that the canal itself is 120 miles long but only 670 feet wide, this is an impressive amount of traffic. The Suez Canal is important to Europe because it provides access to oil from the Middle East. It also serves as an important strategic asset for the United States, as it is used routinely by the U.S. Navy to move surface combatants between the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Thanks to a bilateral arrangement between Egypt and the United States, the U.S. Navy enjoys priority access to the canal.133

- The journey through the narrow waterway is no easy task for large surface combatants. The canal was not constructed with the aim of accommodating 100,000-ton aircraft carriers and therefore exposes a larger ship to attack. For this reason, different types of security protocols are followed, including the provision of air support by the Egyptian military.134 These security protocols, however, are not foolproof. In April 2021, the Suez Canal was closed for more than 11 days after a container ship blocked the waterway, creating a 360-ship traffic jam that disrupted almost 13 percent of global maritime traffic. This crisis proves that ever-larger container ships transiting strategic choke points are prone to accidents that can lead to massive disruptions of both global maritime trade and U.S. maritime security.135

- Strait of Hormuz. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the Strait of Hormuz, which links the Persian Gulf with the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, “is the world’s most important oil chokepoint because of the large volumes of oil that flow through the strait.”136 In 2020, its daily oil flow averaged “around 18 million barrels” per day, or the equivalent of about “[o]ne fifth of global oil supply.”137

- Given the extreme narrowness of the passage and its proximity to Iran, shipping routes through the Strait of Hormuz are particularly vulnerable to disruption. Since 2021, Iran has harassed, attacked, and interfered with 15 internationally flagged merchant ships according to the White House and the Pentagon. More recently, in April and May 2023, Iran seized two oil tankers. In response, the U.S. Navy warships stationed in the Persian Gulf increased their patrols.138 The U.S. needs a naval presence and port access to countries that border the Strait of Hormuz to maintain awareness of Iran’s illicit drug and weapons smuggling.139

- Bab el-Mandeb Strait. The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is a strategic waterway located between the Horn of Africa and Yemen that links the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. Exports from the Persian Gulf and Asia that are destined for Western markets must pass through the strait en route to the Suez Canal. Because the Bab el-Mandeb Strait is 18 miles wide at its narrowest point, passage is limited to two channels for inbound and outbound shipments.140

Maritime Prepositioning of Equipment and Supplies. The U.S. military has deployed noncombatant maritime prepositioning ships (MPS) containing large amounts of military equipment and supplies in strategic locations from which they can reach areas of conflict relatively quickly as associated U.S. Army or Marine Corps units located elsewhere arrive in the area. The British Indian Ocean Territory of Diego Garcia, an island atoll, hosts the U.S. Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia, which supports prepositioning ships that can supply Army or Marine Corps units deployed for contingency operations in the Middle East.

Conclusion

For the foreseeable future, the Middle East region will remain a key focus for U.S. military planners. Once considered relatively stable, mainly because of the ironfisted rule of authoritarian regimes, the area is now highly unstable and a breeding ground for terrorism.

Overall, regional security has deteriorated in recent years. Even though the Islamic State (or at least its physical presence) appears to have been defeated, Iran is a formidable regional menace. Iraq has restored its territorial integrity since the defeat of ISIS, but the political situation and future relations between Baghdad and the U.S. will remain difficult as long as Iran retains control of powerful Shia militias that it uses to intimidate Iraqi political leaders.141 Although the regional dispute with Qatar has been resolved, U.S. relations in the region will remain complex and difficult to manage. U.S. military operations, however, continue uninterrupted.

Many of the borders created after World War I are under significant stress. In countries like Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, the supremacy of the nation-state is being challenged by non-state actors that wield influence, power, and resources comparable to those of small states. The region’s principal security and political challenges are linked to the unrealized aspirations of the Arab Spring, surging transnational terrorism, and meddling by Iran, which seeks to extend its influence in the Islamic world. These challenges are made more difficult by the Arab–Israeli conflict, Sunni–Shia sectarian divides, the rise of Iran’s Islamist revolutionary nationalism, and the proliferation of Sunni Islamist revolutionary groups. In addition, the China-brokered rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia and Beijing’s regionwide infrastructure investments are a warning to U.S. policymakers that neglect of long-standing allies leaves behind power vacuums that America’s enemies are only too capable of exploiting to their own advantage.

For decades, the United States has relied on its incomparable ability to project power in response to crises, and many U.S. operations and contingency plans depend on time-phased force deployment from the continental U.S. to operations theaters. This requires secure air and sea lanes of communication as well as secure air and sea bases of debarkation. Neither is assured in a theater conflict as Iran now possesses the ability to threaten three of the region’s strategic choke points (the Strait of Hormuz, Bab al-Mandeb, and the Suez Canal) as well as U.S. bases and ports along the Arabian Sea within range of a growing and increasingly accurate Iranian ballistic missile inventory.142

Thanks to its decades of military operations in the Middle East, the U.S. has developed tried-and-tested procedures for operating in the region. Personal links between allied armed forces are also present. Joint training exercises improve interoperability, and U.S. military educational courses that are regularly attended by officers (and often royals) from the Middle East give the U.S. an opportunity to influence some of the region’s future leaders.

America’s relationships in the region are based pragmatically on shared security and economic concerns. As long as these issues remain relevant to both sides, the U.S. is likely to benefit from cooperation with partners and allies in the Middle East when shared interests are threatened.

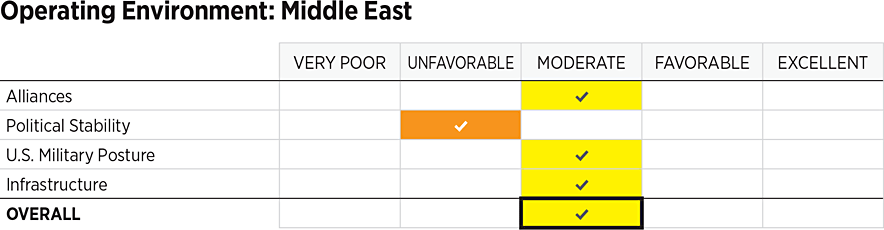

Scoring the Middle East Operating Environment

As noted at the beginning of this section, various aspects of the region facilitate or inhibit the ability of the U.S. to conduct military operations to defend its vital national interests against threats. Our assessment of the operating environment uses a five-point scale that ranges from “very poor” to “excellent” conditions and covers four regional characteristics of greatest relevance to the conduct of military operations:

- Very Poor. Significant hurdles exist for military operations. Physical infrastructure is insufficient or nonexistent, and the region is politically unstable. The U.S. military is poorly placed or absent, and alliances are nonexistent or diffuse.

- Unfavorable. A challenging operating environment for military operations is marked by inadequate infrastructure, weak alliances, and recurring political instability. The U.S. military is inadequately placed in the region.

- Moderate. A neutral to moderately favorable operating environment is characterized by adequate infrastructure, a moderate alliance structure, and acceptable levels of regional political stability. The U.S. military is adequately placed.

- Favorable. A favorable operating environment includes adequate infrastructure, strong alliances, and a stable political environment. The U.S. military is well placed for future operations.

- Excellent. An extremely favorable operating environment includes well-established and well-maintained infrastructure, strong and capable allies, and a stable political environment. The U.S. military is well placed to defend U.S. interests.

The key regional characteristics consist of:

- Alliances. Alliances are important for interoperability and collective defense, as allies are more likely to lend support to U.S. military operations. Indicators that provide insight into the strength or health of an alliance include whether the U.S. trains regularly with countries in the region, has good interoperability with the forces of an ally, and shares intelligence with nations in the region.

- Political Stability. Political stability brings predictability for military planners when considering such things as transit, basing, and overflight rights for U.S. military operations. The overall degree of political stability indicates whether U.S. military actions would be hindered or enabled and reflects, for example, whether transfers of power are generally peaceful and whether there have been any recent instances of political instability in the region.

- U.S. Military Positioning. Having military forces based or equipment and supplies staged in a region greatly facilitates the ability of the United States to respond to crises and presumably to achieve success in critical “first battles” more quickly. Being routinely present in a region also helps the U.S. to remain familiar with its characteristics and the various actors that might either support or try to thwart U.S. actions. With this in mind, we assessed whether or not the U.S. military was well positioned in the region. Again, indicators included bases, troop presence, prepositioned equipment, and recent examples of military operations (including training and humanitarian) launched from the region.

- Infrastructure. Modern, reliable, and suitable infrastructure is essential to military operations. Airfields, ports, rail lines, canals, and paved roads enable the U.S. to stage, launch, and logistically sustain combat operations. We combined expert knowledge of regions with publicly available information on critical infrastructure to arrive at our overall assessment of this metric.143

The U.S. has developed an extensive network of bases in the Middle East region and has acquired substantial operational experience in combatting regional threats. At the same time, however, many of America’s allies are hobbled by political instability, economic problems, internal security threats, and mushrooming transnational threats. Although the region’s overall score remains “moderate,” as it was last year, it is in danger of falling to “poor” because of political instability and growing bilateral tensions with allies over the security implications of the proposed nuclear agreement with Iran and how best to fight the Islamic State.

With this in mind, we arrived at these average scores for the Middle East (rounded to the nearest whole number):

- Alliances: 3—Moderate

- Political Stability: 2—Unfavorable

- U.S. Military Positioning: 3—Moderate

- Infrastructure: 3—Moderate

Leading to a regional score of: Moderate

Endnotes

[1] Forum for American Leadership, U.S. Strategic Interests in the Middle East and North Africa in Great Power Competition, October 29, 2021, https://forumforamericanleadership.org/wp-content/uploads/MENA-Vital-National-Security-Interests-FINAL.pdf (accessed October 25, 2023). President Jimmy Carter’s Presidential Directive 63, dated January 15, 1981, commonly referred to as the Carter Doctrine, reflected the importance of the region, the vital U.S. interests at stake, and a corresponding commitment to establish and maintain a significant presence in the region and develop the capabilities of our partners and allies to defend them. Jimmy Carter, “Address by President Carter on the State of the Union Before a Joint Session of Congress,” January 23, 1980, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1977-80v01/d138 (accessed October 25, 2023); U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Oil and Petroleum Products Explained: Oil Imports and Exports,” https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/imports-and-exports.php#:~:text=Oil%20and%20petroleum%20products%20explained%20Oil%20imports%20and,companies%20purchase%20imported%20crude%20oil%20and%20gasoline%20 (accessed October 25, 2023); U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Petroleum & Other Liquids: Petroleum Supply Monthly,” February 2023, https:// www.eia.gov/petroleum/supply/monthly/ (accessed October 25, 2023); Bradley Olson, “U.S. Becomes Net Exporter of Oil, Fuels for First Time in Decades,” The Wall Street Journal, December 6, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-becomes-net-exporter-of-oil-fuels-for-first-time-in-decades-1544128404 (accessed October 25, 2023); Leo Hindery Jr. and Abbas “Eddy” Zuaiter, “The Middle East and Its Role in the Global Economy,” Middle East Institute, May 13, 2019, https://www.mei.edu/publications/middle-east-and-its-role-global-economy (accessed October 25, 2023); Brent Sadler, “What the Closing of the Suez Canal Says About U.S. Maritime Security,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, April 12, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/what-the-closing-the-suez-canal-says-about-us-maritime-security; Statista, “Number of Ships Passing Through the Suez Canal from 1976 to 2022,” https://www.statista.com/statis-tics/1252568/number-of-transits-in-the-suez-canal-annually (accessed October 25, 2023); Amjad Ahmad, “The Middle East Is a Growing Marketplace, Not Just a War Zone,” Atlantic Council MENASource, September 21, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/the-middle-east-is-a-growing-marketplace-not-just-a-war-zone (accessed October 25, 2023); and Matt Burgess, “The Most Vulnerable Place on the Internet,” Wired, November 2, 2022, https://www.wired.com/story/submarine-internet-cables-egypt (accessed October 25, 2023).

[2] For example, during a 1916 meeting in Downing Street, Sir Mark Sykes, Britain’s lead negotiator with the French on carving up the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, pointed to the map and told the Prime Minister that for Britain’s sphere of influence in the Middle East, “I should like to draw a line from the e in Acre [modern-day Israel] to the last k in Kirkuk [modern-day Iraq].” See James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle That Shaped the Middle East (London: Simon & Schuster U.K., 2011), pp. 7–20. See also Margaret McMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (New York: Random House, 2003).

[3] S.B., “What Is the Difference Between Sunni and Shia Muslims?” The Economist, updated September 23, 2016, http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2013/05/economist-explains-19/ (accessed May 25, 2023).

[4] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Young People in MENA: Coming of Age in a Context of Structural Challenges and Global Trends,” Chapter 1 in Youth at the Centre of Government Action (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022). pp. 1–20, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/youth-at-the-centre-of-government-action_bcc2dd08-en#page9 (accessed May 25, 2023).

[5] Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, “Data/Graphs: OPEC Share of World Crude Oil Reserves, 2022,” https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/330.htm (accessed May 25, 2023).

[6] Tables, “The 10 Largest Oil Producers and Share of Total World Oil Production in 2022” and “The 10 Largest Oil Consumers and Share of Total World Oil Consumption in 2021,” in U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): What Countries Are the Top Producers and Consumers of Oil?” last updated May 1, 2023, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=709&t=6 (accessed May 27, 2023).

[7] Grant Smith, “OPEC Output Hit 30-Year High During the Saudi–Russia Price War,” World Oil, May 1, 2020, https://www.worldoil.com/news/2020/5/1/opec-output-hit-30-year-high-during-the-saudi-russia-price-war (accessed May 25, 2023).

[8] BBC News, “Ukraine Conflict: Petrol at Fresh Record as Oil and Gas Prices Soar,” March 7, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-60642786 (accessed May 25, 2023).

[9] James Phillips, “Biden’s Burnt Bridges Exacerbate Ukraine-Related Oil Crisis,” The Daily Signal, March 11, 2022, https://www.dailysignal.com/2022/03/11/bidens-burnt-bridges-exacerbate-ukraine-related-oil-crisis (accessed May 25, 2023).

[10] Peter St. Onge, “OPEC+ Cuts Raise Fears of Inflation, Dollar Erosion,” The Washington Times, April 4, 2023, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2023/apr/4/opec-cuts-raise-fears-of-inflation-dollar-erosion/ (accessed May 25, 2023).

[11] FocusEconomics, “The World’s Top 5 Largest Economies in 2026,” FocusEconomics, updated November 2022, https://www.focus-economics.com/blog/the-largest-economies-in-the-world (accessed May 25, 2023).

[12] U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, “Japan—Country Commercial Guide,” last published date November 4, 2022, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/japan-market-overview (accessed May 25, 2023).