Asia

Jeff M. Smith, Bruce Klingner, Michael Cunningham, Bryan Burack, and Andrew J. Harding

Asia has always been vital to the protection and advancement of America’s economic and security interests. One of the first ships to sail under an American flag was the aptly named Empress of China, which inaugurated America’s participation in the lucrative China trade in 1784. In the more than two centuries since then, the United States government has maintained that allowing any single nation to dominate Asia would be against America’s interests. The region is home to too many important markets and resources for the United States to be denied access. Thus, beginning with U.S. Secretary of State John Hay’s “Open Door” policy toward China in the 19th century, the United States has worked to prevent the rise of a regional hegemon in Asia, whether it was imperial Japan, the Soviet Union, or China itself.

In the 21st century, Asia’s importance to the United States has continued to grow. Asia is a key source of natural resources and plays a crucial role in countless global supply chains. The sea lines of communication that run through the Pacific and Indian Oceans host the vast majority of sea-borne global trade. Today, six of America’s top 10 trading partners are found in Asia, including China (third); Japan (fourth); South Korea (sixth); Vietnam (seventh); India (ninth); and Taiwan (tenth).1 The extent of America’s economic integration with Asia and Asian supply chains was demonstrated most starkly by the COVID-19 pandemic as the American economy struggled with import shortages of essential goods including basic pharmaceutical products and key electronics components.

The U.S. also has several key security interests in Asia, including a variety of treaty allies and important security partners. The region has several of the world’s largest and most capable militaries, including those of China, India, Japan, Russia, Pakistan, and North and South Korea. Additionally, five Asian states—China, North Korea, India, Pakistan, and Russia—possess nuclear weapons.

The region is a focus of American security concerns for a variety of reasons:

- The region has a notable legacy of conflict: Both of the two major “hot” wars fought by the United States during the Cold War—Korea and Vietnam—were fought in Asia.

- The region is home to America’s top external security threat—China.

- The region is characterized by a number of military flashpoints, territorial disputes, and rivalries, including the India–Pakistan dispute over Kashmir, persistent tensions with North Korea, and a wide variety of active territorial disputes between China and its neighbors, including Taiwan, Japan, India, the Philippines, Bhutan, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Lesser territorial disputes also exist between Japan and Russia and between Korea and Japan.

Several of these unresolved differences could devolve into war. Growing Chinese air and sea incursions around Taiwan and indications that General Secretary Xi Jinping has ordered the People’s Liberation Army to be prepared for an invasion of the island by 2027 have generated increased concern about the potential for military conflict in the Taiwan Strait. The situation on the Korean Peninsula remains perpetually tense with Pyongyang expanding its missile arsenal and testing increasingly capable long-range missiles annually. China’s growing and increasingly potent naval capabilities, bolstered by a massive “maritime militia,” are also generating alarm in Washington and among numerous treaty allies and security partners. Meanwhile, the disputed China–India border has grown considerably more volatile since a series of violent and deadly confrontations in 2020.

Contributing further to instability, the region lacks a robust political–security architecture. There is no Asian equivalent of NATO despite an ultimately failed mid-20th century effort to forge a parallel multilateral security architecture through the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Regional diplomatic forums like the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and groupings like the ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus) constitute the patchwork political architecture.

The Asian security landscape has been marked by a combination of bilateral alliances, mostly centered on the United States, and efforts by individual nations to maintain their own security. In recent years, these core aspects of the regional security architecture have been supplemented by “minilateral” consultations like the U.S.–Japan–Australia and India–Japan–Australia trilaterals; the U.S.–Japan–Australia–India quadrilateral dialogue (popularly known as the Quad); and the new Australia–U.K.–U.S. (AUKUS) agreement.

Nor is Asia undergirded by any significant economic architecture. Despite substantial trade and expanding value chains among the various Asian states, as well as with the rest of the world, formal economic integration is limited. There are many trade agreements among the nations of the region and among these nations and countries outside of Asia, most prominently the 15-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and 11-nation Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), neither of which includes the U.S. However, there is no counterpart to the European Union or even to the European Economic Community or the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to European economic integration.

ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) is a looser agglomeration of disparate states, although they have succeeded in expanding economic linkages among themselves over the past 50 years through a range of economic agreements like the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). The South Asia Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC), which includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, has been less effective, both because of the lack of regional economic integration and because of the historical rivalry between India and Pakistan.

Important Alliances and Bilateral Relations in Asia

The keys to a robust U.S. security presence in the Western Pacific are America’s alliances with Japan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), the Philippines, Thailand, and Australia. These formal alliances are supplemented by close security relationships with New Zealand and Singapore, an emerging strategic partnership with India, and evolving relationships with Southeast Asian partners like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The U.S. also has a robust unofficial relationship with Taiwan.

The United States also benefits from the interoperability gained from sharing common weapons and systems with many of its allies. Many nations, for example, have equipped their ground forces with M-16/M-4–based infantry weapons and share the same 5.56 mm ammunition. They also field F-15, F-16, and F-35 combat aircraft and employ LINK-16 data links among their naval forces. Australia, Japan, and South Korea are partners in production of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, and all three countries have taken delivery of the aircraft. Partners like India and Australia operate American-made P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft and C-17 transport aircraft.

In addition, several “foundational” military agreements with regional partners and allies allow for the sharing of encrypted communications data and equipment, access to each other’s military facilities, and the ability to refuel each other’s air and naval vessels in theater. In the event of conflict, the region’s various air, naval, and even land forces would therefore be able to share information in such key areas as air defense and maritime domain awareness. This advantage is enhanced by the ongoing range of bilateral and multilateral exercises, which acclimate various forces to operating together and familiarize both American and local commanders with each other’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), as well as training, tactics, and (in some cases) war plans.

While it does not constitute a formal alliance, in November 2017, Australia, Japan, India, and the U.S. reconstituted the Quad.2 Officials from the four countries agreed to meet in the quadrilateral format twice a year to discuss ways to strengthen strategic cooperation and combat common threats. In 2019, the group held its first meeting at the ministerial level and added a counterterrorism tabletop exercise to its agenda.3 In 2020, officials from the four countries participated in a series of conference calls to discuss responses to the COVID-19 pandemic that also included government representatives from New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam.4 In March 2021, the leaders of the four nations held their first virtual summit, marking a new level of interaction.5 In September 2021, the four leaders held the first in-person Quad summit, which was followed by a second in-person summit in 2022.6

Japan. The U.S.–Japan defense relationship is the linchpin of America’s network of relations in the Western Pacific. The U.S.–Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, signed in 1960, provides for a deep alliance between two of the world’s largest economies and most sophisticated military establishments. Changes in Japanese defense policies are now enabling an even greater level of cooperation on security issues, both between the two allies and with other countries in the region.

Since the end of World War II, Japan’s defense policy has been distinguished by Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, which states in part that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.”7 In effect, this article prohibits the use of force by Japan’s governments as an instrument of national policy.

However, Japan’s legal interpretation of what is allowed under its peace constitution is not static. It has evolved in response to growing regional threats, Japan’s improving military capabilities, and Tokyo’s perception of the strength of its alliance with Washington. Japan has gradually adopted missions and deployed weapons that originally were deemed to be unconstitutional.

One such policy was a prohibition against “collective self-defense.” For decades, Japan recognized that nations have a right to employ their armed forces to help other states defend themselves (in other words, to engage in collective defensive operations) but rejected that policy for itself: Japan would employ its forces only in defense of Japan. This changed in 2015 when Japan passed legislation that enabled its military to exercise collective self-defense in certain cases involving threats to an ally that has come under attack.

Another dramatic shift was Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s decision in December 2022 that Japan would develop long-range missile counterstrike capabilities. Debate about the constitutionality of such capability has raged since 1956 when then-Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama assessed that attacking enemy bases could be justified in terms of the right of self-defense. Since then, subsequent Japanese administrations have consistently asserted that Japan has the authority to conduct attacks on enemy targets but chooses not to develop the means to do so.

Citing the escalating Chinese and North Korean missile arsenals, the Kishida administration declared that relying solely on Japanese missile defenses or U.S. strike capabilities to defend against missile threats had become increasingly untenable. Instead, Japan must augment its missile defenses by adding capabilities that would enable it to mount effective counterstrikes against an opponent on its territory to prevent further attacks.

Kishida also broke with long-standing precedent by pledging to raise Japanese defense spending to 2 percent of current gross domestic product (GDP), thereby doubling the self-imposed limit of 1 percent that Tokyo had followed for decades.8 The Kishida administration emphasized that Japan’s rapid and extensive defense buildup required a sustained level of expenditures rather than a temporary increase in spending. Defense spending will be increased to a five-year total of 43 trillion yen ($323 billion) from 2023–2027, and the annual defense budget will be 10 trillion yen ($75 billion), making Japan the world’s third-biggest military spender after the United States and China.9

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused a significant shift in the Japanese public’s perception of their country’s threat environment. The Japanese had been aware of the growing Chinese and North Korean threats, but Vladimir Putin’s invasion made clear that their perception of a “post-war world” was an illusion and that large-scale military conflicts between major powers remained a realistic threat. The Russian invasion of Ukraine crystallized Japanese fears of a possible Chinese conflict in Taiwan and was a wakeup call on the need to augment Japan’s military.

Before the war in Ukraine, the Japanese populace had feared that loosening any restrictions on Japan’s military risked an inexorable return to the country’s militaristic past. The war in Ukraine seemingly caused an overnight sea change in Japanese perceptions. Public opinion polls show strong majorities favoring greater defense spending and a counterstrike capability. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s 2015 implementation of a policy of collective self-defense led to fierce debates in the national legislature and large public protests. By contrast, the bold security steps announced by the Kishida administration in December 2022 elicited strong public support without sparking any protests.

Despite developing a formidable military force, Japan still relies heavily on the United States—and Washington’s extended deterrence guarantee of nuclear, conventional, and missile defense forces—for its security. To strengthen military coordination with the United States, Tokyo has pledged to establish a permanent joint headquarters to unify command of the ground, naval, and air forces.

Currently, the Self-Defense Forces are stovepiped with insufficient ability to communicate, plan, or operate across services. Japan’s inability to conduct joint operations across its own military services has inhibited its capacity for combined operations with U.S. forces. By designating a single joint commanding general, Japan will now be able to coordinate more effectively with U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) and its combatant commander. Despite this improvement, however, the separate and parallel command structure that Japan and the United States will continue to have is a major shortcoming compared with the integrated command relationship that the U.S. military has with South Korea or NATO allies.

As part of its military relationship with Japan, the United States maintains ”approximately 54,000 military personnel” and 8,000 Department of Defense (DOD) civilian and contractor employees in Japan under the rubric of U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ).10 These forces include, among other things, a forward-deployed carrier battle group centered on the USS Ronald Reagan; an amphibious ready group at Sasebo centered on the LHA-6 America, an aviation-optimized amphibious assault ship; and the bulk of the Third Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF) on Okinawa. U.S. forces exercise regularly with their Japanese counterparts, and this collaboration has expanded in recent years to include joint amphibious exercises as well as air and naval exercises.

The American presence is supported by a substantial American defense infrastructure throughout Japan, including Okinawa. These bases provide key logistical and communications support for U.S. operations throughout the Western Pacific, cutting travel time substantially compared with deployments from Hawaii or the West Coast of the United States. They also provide key listening posts for the monitoring of Russian, Chinese, and North Korean military operations. This capability is supplemented by Japan’s growing array of space systems, including new reconnaissance satellites.

During bilateral Special Measures Agreement negotiations, the Trump Administration sought a 400 percent increase in Japanese contributions for renumeration above the cost of stationing U.S. troops in Japan. Late in 2021, Japan’s Asahi Shimbun reported that Japan had agreed to “ramp up its annual host-nation support for U.S. forces stationed in Japan.” Specifically:

Under the agreement, Japan’s yearly contribution to host U.S. bases will total 1,055.1 billion yen ($9.2 billion) for the five-year period from fiscal 2022 through fiscal 2026. This translates into an annual average payment of about 211 billion yen, nearly 10 billion yen more than the 201.7 billion yen Japan pays under the program for the current fiscal year….

Under the new agreement, Japan’s funding for facilities within U.S. bases, such as bomb shelters to protect aircraft, will increase, while Japan’s outlays for utilities costs will be reduced gradually in five years to 13.3 billion yen from 23.4 billion yen for the current fiscal year. This indicates a shift in the focus of the program from financing running costs for U.S. forces to bolstering operational capabilities.11

In January 2022, the U.S. Department of Defense stated that U.S. and Japanese officials had “reaffirmed that the total amount of Japan’s Facilities Improvement Program (FIP) funding will be 164.1 billion yen to fund prioritized projects, subject to the completion of all necessary procedures for such budget request….”12

The United States has long sought to expand Japanese participation in international security affairs. Japan’s political system, grounded in the country’s constitution, legal decisions, and popular attitudes, has generally resisted this effort. However, in recent years, Tokyo has become increasingly alarmed by China’s surging defense expenditures, rapidly expanding and modernizing military capabilities, and escalating aerial and maritime incursions into Japan’s territorial waters and contiguous areas. In response, Japan has reoriented its forces so that they can better counter the Chinese threat to its remote southwest islands. It also has acquired new capabilities, built new facilities, deployed new units and augmented others, improved its amphibious warfare capabilities, increased its air and sea mobility, and enhanced its command-and-control capabilities for joint and integrated operations.13

Recently, the growing potential for a Taiwan crisis has led senior Japanese officials to issue increasingly bold public statements of support for Taipei and align Japan’s national interests more directly with the protection of Taiwan’s security. However, there have been no declared policy changes, and Japan has not pledged to intervene directly in a military conflict to defend Taiwan or even to allow U.S. defense of Taiwan from bases in Japan.

Contentious historical issues from Japan’s brutal 1910–1945 occupation of the Korean Peninsula have been serious enough to torpedo efforts to improve defense cooperation between Seoul and Tokyo. South Korean–Japanese relations took a major downturn in 2018 when the South Korean Supreme Court ruled that Japanese companies could be forced to pay reparations for forced labor.14 In December 2018, an incident between a South Korean naval ship and a Japanese air force plane further exacerbated tensions. Japan responded in July 2019 by imposing restrictions on exports to South Korea of three chemicals that are critical to the production of semiconductors and smartphones.15 Seoul then threatened to withdraw from the bilateral General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), which enables the sharing of classified intelligence and military information on the North Korean nuclear and missile threat. The Moon Jae-in administration relented and maintained the agreement, but there was public criticism of U.S. pressure.

In March 2023, President Yoon Suk Youl, who had been elected to succeed Moon in March 2022, took a bold and politically risky step to improve bilateral relations with Japan by announcing that Korean rather than Japanese companies would provide compensation to Korean forced labor victims. Yoon’s decision led to the cancellation of Japanese export restrictions, progress toward enhancing economic trade, and discussion on expanding military cooperation toward the common North Korean threat. Yoon’s decision, however, was criticized by a majority of South Koreans, indicating a lack of support that could hinder further security enhancements.

Republic of Korea. The United States and the Republic of Korea signed their Mutual Defense Treaty in 1953. That treaty codified the relationship that had grown from the Korean War, when the United States dispatched troops to help South Korea defend itself against invasion by Communist North Korea. Since then, the two states have forged an enduring alliance supplemented by a substantial trade and economic relationship that includes a free trade agreement.16

The U.S. is committed to maintaining 28,500 troops on the Korean Peninsula. This presence is centered mainly on the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division, rotating brigade combat teams, and a significant number of combat aircraft.

The U.S.–ROK defense relationship involves one of the more integrated and complex command-and-control structures. A United Nations Command (UNC) established in 1950 was the basis for the American intervention and remained in place after the armistice was signed in 1953. UNC has access to seven bases in Japan to support U.N. forces in Korea.

Although the 1953 armistice ended the Korean War, UNC retained operational control (OPCON) of South Korean forces until 1978, when it was transferred to the newly established Combined Forces Command (CFC). Headed by the American Commander of U.S. Forces Korea, who is also Commander, U.N. Command, CFC reflects an unparalleled degree of U.S.–South Korean military integration. CFC returned peacetime operational control of South Korean forces to Seoul in 1994. If war became imminent, South Korean forces would become subordinate to the CFC commander, who in turn remains subordinate to both countries’ national command authorities.

In 2007, then-President Roh Moo-hyun requested that the United States return wartime OPCON of South Korean forces to Seoul. Under the plan, the CFC commander would be a South Korean general with a U.S. general as deputy commander. The U.S. general would continue to serve as commander of UNC and U.S. Forces Korea (USFK). The CFC commander, regardless of nationality, would always remain under the direction and guidance of U.S. and South Korean political and military national command authorities.

This decision engendered significant opposition within South Korea and raised serious military questions about the transfer’s impact on unity of command. Late in 2014, Washington and Seoul agreed to postpone the scheduled wartime OPCON transfer and instead adopted a conditions-based rather than timeline-based policy.

President Moon Jae-in advocated for an expedited OPCON transition during his administration, but critical conditions, including improvement in South Korean forces and a decrease in North Korea’s nuclear program, had not been met.17 Moon’s successor, Yoon Suk Youl, criticized his push for a premature return of wartime OPCON before Seoul had fulfilled the agreed-upon conditions.

South Korea has fought alongside the United States in nearly every significant conflict since the Korean War. Seoul sent 300,000 troops to the Vietnam War, and 5,000 of them were killed. At one point, it fielded the third-largest troop contingent in Iraq after the United States and Britain. It also has conducted anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia and has participated in peacekeeping operations in Afghanistan, East Timor, and elsewhere. In spite of its support for multinational crisis response, however, South Korea’s defense planning is focused on North Korea, especially as Pyongyang has deployed its forces in ways that optimize a southward advance and has carried out several penetrations of ROK territory by ship, submarine, commandos, and drones.

In response to Pyongyang’s expanding nuclear strike force, South Korea created a “Three Axis” tiered defense strategy comprised of Kill Chain (preemptive attack); the Korea Air and Missile Defense (KAMD) system; and the Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) system. The South Korean military is a sizeable force with advanced weapons and innovative military education and training. South Korean military spending has increased, and Seoul appears to be procuring the right mix of capabilities. U.S.–South Korean interoperability has improved, partly because of continued purchases of U.S. weapons systems.

Over the past several decades, the American presence on the peninsula has slowly declined. In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon withdrew the 7th Infantry Division, leaving only the 2nd Infantry Division on the peninsula. Those forces have been positioned farther back from North Korea so that few Americans are now deployed on the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

Traditionally, U.S. military forces regularly engaged in major exercises with their ROK counterparts, including the Key Resolve and Foal Eagle series, both of which involved the deployment of substantial numbers of U.S. forces to the Korean Peninsula. However, after the 2018 U.S.–North Korean Summit, President Donald Trump announced that he was unilaterally cancelling major bilateral military exercises with South Korea, dismissing them as “very provocative,” “ridiculous,” “unnecessary,” and a “total waste of money.”18 The President made his decision without consulting the DOD, U.S. Forces Korea, or allies South Korea and Japan. During the next four years, the U.S. and South Korea cancelled numerous large-scale exercises and reduced the “size, scope, volume, and timing” of other allied military exercises in South Korea without any change in North Korean military activity19 or any reciprocal diplomatic gesture in return for the unilateral U.S. concession.

In 2022, South Korean President Yoon and American President Joe Biden agreed to expand the scope and scale of bilateral combined military exercises to repair the degradation of allied deterrence and defense capabilities since 2018. Biden also agreed to resume the rotational deployment of U.S. strategic assets—bombers, aircraft carriers, and dual-capable aircraft—to the Korean Peninsula that Trump had also cancelled in 2018.20

In late 2022, Washington and Seoul conducted wide-ranging air, naval, and ground maneuvers on and near the Korean Peninsula. The U.S., South Korea, and Japan also resumed trilateral military exercises after a five-year hiatus. The three countries engaged in anti-submarine and ballistic missile exercises to enhance security coordination against the common North Korean threat. To capitalize on this positive momentum, Washington and Seoul announced that in 2023, they would conduct at least 20 combined training programs commensurate in size to the large-scale Foal Eagle field training exercises of the past.21 The Freedom/Warrior Shield exercises in March 2023 were the largest and longest drills in at least five years.

The ROK government provides substantial resources to defray the costs of U.S. Forces Korea. The bilateral, cost-sharing Special Measures Agreement has offset the non-personnel costs of stationing U.S. forces in South Korea since 1991 and is renegotiated every five years.22 In February 2019, South Korea offered to increase its share of the cost by approximately 8 percent to about $920 million.23 President Trump first demanded “cost plus 50 percent”24 and then demanded a fivefold increase of $5 billion a year and threatened to reduce or remove U.S. forces from South Korea. In April 2021, the Biden Administration signed an agreement accepting an incremental increase in Seoul’s contribution in line with previous agreements, thereby defusing tensions within the alliance.25

South Korea spends 2.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense—more than is spent by any European ally except Poland.26 Seoul absorbs costs not covered in the cost-sharing agreement, including 91 percent ($10.7 billion) of the cost of constructing Camp Humphreys, the largest U.S. base on foreign soil.27

The Philippines. In addition to being America’s longest-standing defense ally in Asia, the Philippines shares a uniquely close and complex relationship with the United States. After more than 300 years of colonial rule, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States at the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in 1898. Over the next four decades, the United States gradually established democratic institutions and provided for increased autonomy, which culminated in full independence in 1946.

During this period, the United States and Filipinos first fought against each other in the Philippine–American war and in other resistance to colonial government and then alongside each other in World War II. The bond forged between the two peoples has persisted into the 21st century. Recent polls show that 80 percent of Filipinos view the United States favorably—a greater share than is reported by some other U.S. defense treaty allies in the Indo-Pacific.28

The United States and the Philippines signed a Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) in 1951. For much of the period between 1898 and the end of the Cold War, the Philippines was home to the largest American bases in the Pacific, centered on the U.S. Navy base in Subic Bay and the complex of airfields that developed around Clark Field (later Clark Air Base), where unparalleled base infrastructure provided replenishment and repair facilities and substantially extended deployment periods throughout the East Asian littoral.

These bases, simultaneously controversial reminders of the colonial era and generators of economic activity, provided for substantial lease payments to the Philippines government. In 1991, the United States decided to abandon Clark Air Base after significant damage from a volcanic eruption29 and offered the Philippines a reduced payment for the continued use of Subic alone.30 The Philippines rejected the offer, thereby compelling the closure of U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay.31

Despite the base closures, U.S.–Philippine military relations remained close, and assistance began to increase again after 9/11 as U.S. forces supported Philippine efforts to counter Islamic terrorist groups, including the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), in the South of the archipelago. From 2002–2015, the U.S. rotated 500–600 special operations forces regularly through the Philippines to assist in counterterrorism operations. That operation, Joint Special Operations Task Force–Philippines (JSOTF–P), ended during the first part of 2015.32

The U.S. presence in Mindanao continued at a reduced level until the Trump Administration, alarmed by the terrorist threat there, began Operation Pacific Eagle–Philippines (OPE–P). The presence of 200–300 American advisers proved very valuable to the Philippines in its 2017 battle against Islamist insurgents in Marawi.33

U.S.–Philippine defense cooperation underwent a period of instability beginning in February 2020 when the sitting Philippine President announced a decision to abrogate the 1998 U.S.–Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). An instrument of the MDT, the VFA specifies the procedures governing the deployment of U.S. forces and equipment to the Philippines and governs the application of domestic Philippine law to U.S. personnel, which is the most substantive part of the VFA and historically the most controversial. During this period, the VFA operated on successive six-month extensions until the Philippines retracted its intention to terminate the agreement in July 2021.34 Preservation of the VFA underpins extensive joint military activities, which reportedly will include “more than 500 activities together throughout [2023].”35

In another sign of strengthening U.S.–Philippine defense ties, in April 2023, the two countries designated additional sites under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). The EDCA, signed in 2014, authorizes the rotational deployment of U.S. forces and prepositioning of materiel at agreed locations in the Philippines for security cooperation, joint training, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.36 The four new sites brought the total of agreed locations to nine. Two of the newly announced locations are adjacent to the South China Sea, and two are located in areas of the Philippines that are geographically near Taiwan.37

The U.S. government has long made it clear that any attack on Philippine ships or aircraft or on the Philippine armed forces—for example, by China—would be covered under the U.S.–Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty and would obligate the United States, consistent with its constitutional procedures, to come to the defense of the Philippines.38 In February 2023, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin reaffirmed this commitment, specifying that such an attack anywhere in the South China Sea would invoke U.S. mutual defense commitments.39

Thailand. The U.S.–Thai defense alliance is built on the 1954 Manila Pact, which established the now-defunct SEATO, and the 1962 Thanat–Rusk agreement.40 These were supplemented by the Joint Vision Statements for the Thai–U.S. Defense Alliance of 2012 and 2020.41 In addition, Thailand gained improved access to American arms sales in 2003 when it was designated a “major, non-NATO ally.”

Thailand’s central location has made it an important part of America’s network of alliances in Asia. During the Vietnam War, U.S. aircraft based in Thailand ranged from fighter-bombers and B-52s to reconnaissance aircraft. In the first Gulf War and again in the Iraq War, some of those same air bases were essential for the rapid deployment of American forces to the Persian Gulf. Access to these bases remains critical to U.S. global operations.

U.S. and Thai forces exercise together regularly, most notably in the annual Cobra Gold exercises, which were initiated in 1982. This collaboration builds on a partnership that began with the dispatch of Thai forces to the Korean War, during which Thailand’s approximately 12,000 troops suffered more than 1,200 casualties.42 The Cobra Gold exercise is the world’s longest-running international military exercise43 and one of its largest. The most recent, in 2023, involved more than 6,000 U.S. personnel and featured, in addition to co-host Thailand,44 “full participation from the Republic of Indonesia, Republic of Korea, Republic of Singapore, Japan and Malaysia, as well as other limited participants, planners and observers from more than 20 additional nations.”45 In past years, a small number of Chinese personnel also participated.

While U.S.–Thai security cooperation remains strong, U.S. relations with Thailand overall have faced both persistent strain and acute crises in recent years that are idiosyncratic among U.S. treaty allies. Military coups in 2006 and 2014 limited military-to-military relations for more than a decade. This was due partly to standing U.S. law prohibiting assistance to regimes that result from coups against democratically elected governments and partly to policy choices by the U.S. government.

In 2017, Thailand adopted a junta-drafted constitution that institutionalized elements of military rule. Nonetheless, the United States welcomed Thailand’s first general elections under this constitution in 2019 as “positive signs for a return to a democratic government that reflects the will of the people.”46 Bilateral military engagement has since rebounded with high-level engagement and arms transfers to the Thai military of major systems like Stryker armored vehicles and Black Hawk helicopters. Under the Biden Administration, this trend may lead to the sale of the F-35.47

Thailand is the only Southeast Asian country that was never colonized and has long pursued a hedging strategy that seeks to maintain good relations among competing powers.48 In the post–Cold War era, this tradition has contributed to Thailand’s geopolitical drift away from the U.S. and toward China—a trend that has been further encouraged by the suppression of democratic institutions in Thailand, resulting tensions in U.S.–Thai bilateral relations, China’s amenability to anti-democratic regimes, and expanding Chinese–Thai economic relations. The U.S. and Thailand have differing threat perceptions concerning China, and this has undermined the U.S.–Thai alliance’s clarity of purpose.

Relations between the Thai and Chinese militaries have improved steadily over the years. Thai and Chinese military forces have engaged in joint naval exercises since 2005, joint counterterrorism exercises since 2007, and joint marine exercises since 2010 and conducted their first joint air force exercises in 2015.49 The Thais conduct more bilateral exercises with the Chinese than are conducted by any other military in Southeast Asia.50

Thailand has also purchased Chinese military equipment for many years. Purchases in recent years have included significant buys of battle tanks and armored personnel carriers.51 According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), from 2006 to 2022, China was a significantly bigger supplier than the U.S.52 These deals, however, have not been without difficulty. Thailand’s acquisition of submarines, for example, has been stalled first by a combination of budget restraints, the priority of COVID-19 response, and public protest53 and more recently by Germany’s refusal to allow export of the engines that the boats require.54 Submarines could be particularly critical to Sino–Thai relations because their attendant training and maintenance would require a greater Chinese military presence at Thai military facilities.

Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Republic of Palau. The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), and Republic of Palau55 enjoy a unique defense partnership with the United States. During World War II, the Pacific Islands were vitally important as the U.S. fought to gain a foothold in the Pacific theater in its campaign against Imperial Japan. After World War II, the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands was administered by the U.S. and often used for nuclear testing, most notably the 1954 Castle Bravo test, which involved the largest U.S. bomb ever tested, at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.56 As the FSM, RMI, and Palau gained independence, they elected to enter a special association with the United States.

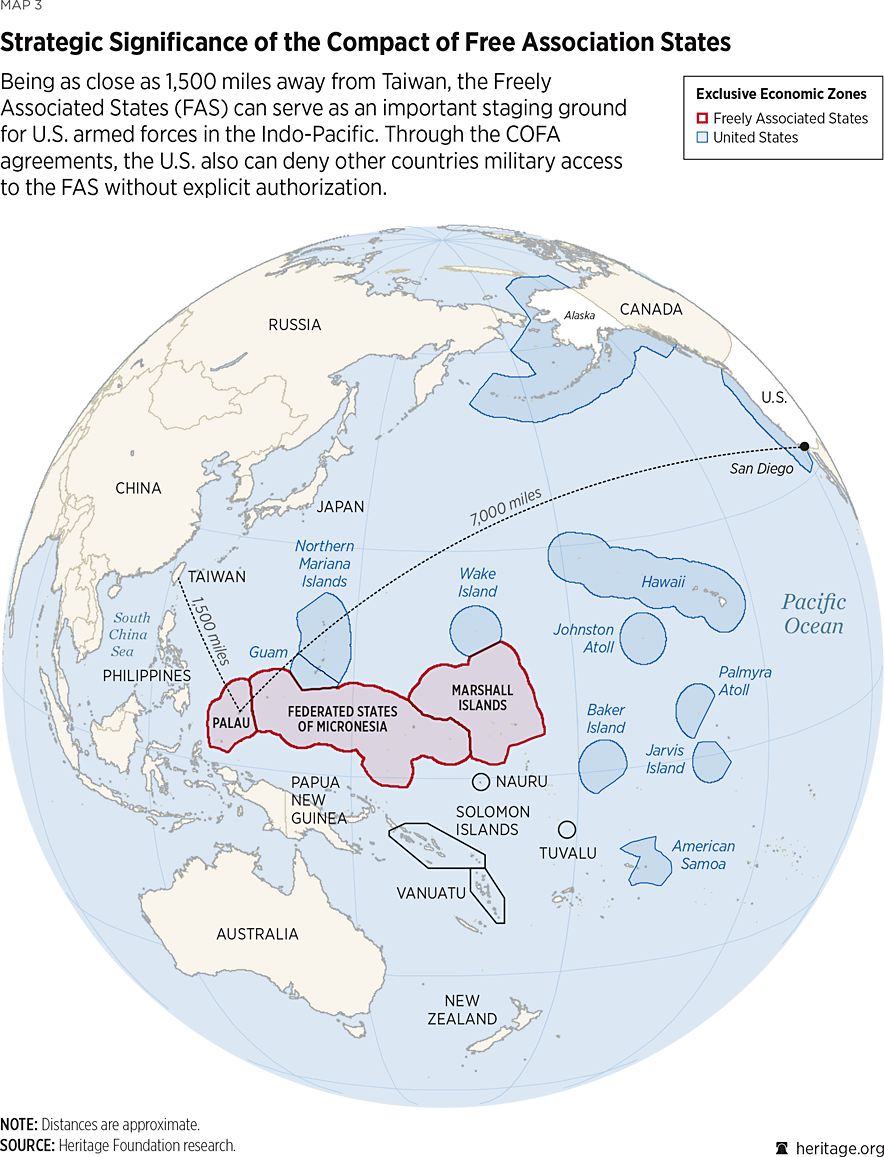

About every 20 years, each of the Freely Associated States (FAS) negotiates a renewal of the Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the U.S. that governs its defense, economic, and immigration affairs. The COFA agreements are strategically important for two primary reasons.

First, they grant the U.S. absolute control of all FAS defense matters. The U.S. exclusively operates armed forces and bases throughout the FAS while being responsible for their protection. Some restrictions apply: The U.S. cannot use weapons of mass destruction in Palauan territory and can store them in the FSM or RMI only during war or emergency.57 Notably, COFA citizens serve in the U.S. armed forces.

Second, the U.S. has the right of strategic denial. Strategic denial allows the U.S. to determine unilaterally which militaries are authorized to enter FAS territories.58 As China’s influence and operations throughout the Pacific Islands grow, including recently in the Solomon Islands, the right to strategic denial becomes increasingly important.59

The current COFA agreements with the FSM and RMI expire on September 30, 2023, and with Palau on September 30, 2024. In 2003, the U.S. provided $3.5 billion in funding to the FSM and RMI.60 The Biden Administration’s FY 2024 budget request includes $7.1 billion over 20 years for the renewal of COFA agreements for all three FAS.61 Renewal is essential for maintaining U.S. power projection and operational flexibility in the Pacific.62

All FAS have a “shiprider” agreement that allows U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) personnel and law enforcement to work with local maritime law enforcement to protect regional resources.63 The USCG opened the Commander Carlton S. Skinner Building, located at USCG Forces Micronesia/Sector Guam, in 2022.64 In 2021, former FSM President David Panuelo, USINDOPACOM Commander Admiral John C. Aquilino, and U.S. Ambassador to the FSM Carmen G. Cantor had reached an agreement to build a new military base in the FSM.65 The RMI hosts the U.S. Army Garrison Kwajalein Atoll, which is the country’s second-largest employer, and the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site.66 In 2012, the Marshall Islands Sea Patrol christened the LOMOR II for maritime inspections and rapid response operations with the support of Japan, Australia, and the United States.67

With about 500 Palauans serving in the U.S. armed forces, Palau has a higher volunteer rate per capita than any U.S. state.68 In 2020, Palau requested that the Pentagon build permanent military bases,69 and a $118 million foundational installation to support the Tactical Mobile Over-the-Horizon Rader is expected to be operational by 202670 with one site along the northern isthmus of Babeldaob and another on Angaur.71 In 2020, the 17th Field Artillery Brigade maneuvered from Guam to Palau as part of the Defense Pacific 20 exercise with a High Mobility Artillery Rocket System.72 In 2021, Secretary of Defense Austin hosted Palauan President Surangel Whipps Jr. to discuss defense-related matters.73 The 1st Air Defense Artillery Battalion, based out of Okinawa, held its first Patriot live-fire exercise in Palau in 2022.74

Australia. Australia is one of America’s most important Indo-Pacific allies. U.S.–Australia security ties date back to World War I when U.S. forces fought under Australian command on the Western Front in Europe. They deepened during World War II when, after Japan commenced hostilities in the Western Pacific, Australian forces committed to the North Africa campaign. As Japanese forces attacked the East Indies and secured Singapore, Australia turned to the United States to bolster its defenses, and American and Australian forces cooperated closely in the Pacific War. Those ties and America’s role as the main external supporter of Australian security were codified in the Australia–New Zealand–U.S. (ANZUS) pact of 1951.

Today, the two nations’ chief defense and foreign policy officials meet annually (most recently in December 2022) in the Australia–United States Ministerial (AUSMIN) process to address such issues of mutual concern as security developments in the Asia–Pacific region, global security and development, and bilateral security cooperation.75 Australia also has long granted the United States access to a number of joint facilities, including space surveillance facilities at Pine Gap, which has been characterized as “arguably the most significant American intelligence-gathering facility outside the United States,”76 and naval communications facilities on the North West Cape of Australia.77

In 2011, U.S. access was expanded with the U.S. Force Posture Initiatives (USFPI), which included Marine Rotational Force–Darwin and Enhanced Air Cooperation. The rotation of as many as 2,500 U.S. Marines for a set of six-month exercises near Darwin began in 2012. The current rotation is comprised of 2,500 Marines that participate in multiple live fire and joint exercises.78 In the past, these forces have deployed with assets that include a MV-22 Osprey squadron, UH-1Y Venom utility and AH-1Z Viper attack helicopters, and RQ-21A Blackjack drones.

The USFPI’s Enhanced Air Cooperation component began in 2017, building on preexisting schedules of activity. New activities include “fifth generation integration, aircraft maintenance integration, aeromedical evacuation (AME) integration, refueling certification, and combined technical skills and logistics training.”79 Enhanced Air Cooperation has been accompanied by the buildout of related infrastructure at Australian bases, including a massive fuel storage facility in Darwin.80 Other improvements are underway at training areas and ranges in Australia’s Northern Territories.81

In 2021, the U.S., Australia, and the U.K., which already enjoyed close security cooperation, inaugurated a new Australia–United Kingdom–United States partnership (AUKUS) initiative. A key component of this initiative is support for Australia’s acquisition of “a conventionally armed, nuclear powered submarine capability at the earliest possible date, while upholding the highest nonproliferation standards.”82 Among other things, the partnership also focuses on improving cooperation in undersea robotic autonomous systems, quantum technologies, artificial intelligence, and hypersonic capabilities.83

On March 13, 2023, the AUKUS partners announced an arrangement under which Australia will acquire nuclear submarines, to be known as SSN-AUKUS, featuring U.K. submarine design and advanced U.S. technology. Both Australia and the U.K. will deploy SSN-AUKUS and intend to begin domestic production before 2030. The U.K. plans to deliver its first SSN-AUKUS in the late 2030s, and Australia plans to deliver its first submarine in the early 2040s. The U.S. intends to sell three and as many as five Virginia–class submarines to Australia in the early 2030s. The agreement also includes increases in funding, training, port and personnel visits, rotations, and infrastructure projects.84 Although maintaining political support for the decades-long commitments may prove challenging, the envisioned pathway should unleash a new era of AUKUS partnership and security in the Indo-Pacific.

This new cutting-edge cooperation under the USFPI and AUKUS comes on top of long-standing joint U.S.–Australia training, the most prominent example of which is Talisman Saber, a series of biannual exercises that involve U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines as well as almost two-dozen ships, multiple civilian agencies, and participants embedded from other partner countries.85 COVID forced the 2021 iteration to downsize, but the 2019 version included more than 34,000 personnel from the U.S. and Australia. The 2023 exercise is scheduled for July 21 to August 4, 2023.86

In April 2023, the government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese released a Defence Strategic Review billed as “the most ambitious review of Defence’s posture and structure since the Second World War.”87 The review assesses that the U.S. is no longer the “unipolar leader of the Indo-Pacific” and recommends that Australia adopt a strategy of denial with a focused force structure that prioritizes the “most significant military risks.”88 China’s strategic intentions, demonstrated by its military buildups and provocative actions in the South China Sea and Pacific Islands, are assessed as likely to have a negative impact on Australian interests.89 The Albanese government either agreed or agreed in-principle to adopt or implement all of the review’s 62 recommendations.90

Singapore. Singapore is America’s closest non-ally partner in the Western Pacific. The agreements that support this security relationship are the 2015 U.S.–Singapore Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA),91 which is an update of a similar 2005 agreement, and the 1990 Memorandum of Understanding Regarding United States Use of Facilities in Singapore, which was renewed in 2019 for another 15 years.92

Pursuant to these agreements and other understandings, Singapore hosts U.S. naval ships and aircraft as well as Logistics Group Western Pacific, principal logistics command unit for the U.S. Seventh Fleet.93 U.S. Navy P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft began rotational deployments to Singapore in 2015,94 and Littoral Combat Ships have deployed to Singapore since 2016.95 The U.S. Air Force began rotational deployments of RQ-4 Global Hawk unmanned aircraft to Singapore in 2023.96 Notably, the Changi Naval Base is capable of hosting U.S. aircraft carriers, which visit regularly with the USS Nimitz conducting the most recent port call in January 2023.97

According to the U.S. Department of State, “[t]he United States has $8.38 billion in active government-to-government sales cases with Singapore under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system” and “[f]rom 2019 through 2021…authorized the permanent export of over $26.3 billion in defense articles to Singapore via Direct Commercial Sales (DCS).”98 In addition, “more than 1,000 Singaporean military personnel participate in training, exercises, and Professional Military Education in the United States,” and “Singapore has operated advanced fighter jet detachments in the continental United States for 27 years.”99

In January 2020, it was announced that Singapore had been “formally approved to become the next customer of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, paving the way for a future sale.”100 Like others of its assets, the four F-35s were to be housed at training facilities in the U.S.101 and perhaps on Guam under an agreement reached in 2019.102 In February 2023, it was reported that “Singapore will exercise a contractual option to acquire eight more F-35B fighter jets, bringing its fleet to 12 aircraft that manufacturer Lockheed Martin will deliver by the end of the decade.”103

New Zealand. For much of the Cold War, U.S. defense ties with New Zealand were similar to those between America and Australia. In 1986, New Zealand was suspended from the 1951 ANZUS treaty for pursuing a “nuclear free zone” and barring nuclear-powered vessels from entering its 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. In 2012 the ban on visits by U.S. nuclear-powered naval vessels was lifted.104

Defense relations improved in the early 21st century as New Zealand committed forces to Afghanistan and dispatched an engineering detachment to Iraq. The 2010 Wellington Declaration and 2012 Washington Declaration, while not restoring full security ties, allowed the two nations to resume high-level defense dialogues.105 As part of this warming of relations, New Zealand rejoined the multinational U.S.-led RIMPAC (Rim of the Pacific) naval exercise in 2012 and has participated in each iteration since then.

In 2013, U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and New Zealand Defense Minister Jonathan Coleman announced the resumption of military-to-military cooperation,106 and in July 2016, the U.S. accepted an invitation from New Zealand to make a single port call, reportedly with no change in U.S. policy to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons on the ship.107 At the time of the visit in November 2016, both sides claimed to have satisfied their respective legal requirements.108 Prime Minister John Key expressed confidence that the vessel was not nuclear-powered and did not possess nuclear armaments, and the U.S. neither confirmed nor denied this.

The November 2016 visit occurred in a unique context, including an international naval review and a relief response to the Kaikoura earthquake. Since then, there have been several other ship visits by the U.S. Coast Guard. In 2017, New Zealand lent one of its naval frigates to the U.S. Seventh Fleet following a deadly collision between the destroyer USS Fitzgerald and a Philippine container ship that killed seven American sailors.109 In November 2021, the guided-missile destroyer USS Howard made a port call in New Zealand.110

New Zealand is a member of the elite Five Eyes intelligence alliance with the U.S., Canada, Australia, and the U.K.111 After a period of record attrition in the New Zealand Defence Force that led to the idling of three naval vessels and early retirement of the country’s P-3 Orion fleet, New Zealand is reportedly considering “the possibility of…becoming a non-nuclear partner of AUKUS” and increasing overall resources allocated to defense.112

Taiwan. When the United States shifted its recognition of the government of China from the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), it also declared certain commitments concerning the security of Taiwan. These commitments are embodied in the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) and the subsequent “Six Assurances.”113

The TRA is an American law, not a treaty. Under the TRA, the United States maintains programs, transactions, and other relations with Taiwan through the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT). Except for the Sino–U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty, which had governed U.S. security relations with Taiwan and was terminated by President Jimmy Carter following the shift in recognition to the PRC, all other treaties and international agreements made between the Republic of China and the United States remain in force.

Under the TRA, it is U.S. policy “to provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character.”114 The TRA also states that the U.S. “will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.”115 The U.S. has implemented these provisions of the act through sales of weapons to Taiwan.

The TRA states that it is also U.S. policy “to consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States”116 and “to maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”117 To this end:

The President is directed to inform the Congress promptly of any threat to the security or the social or economic system of the people on Taiwan and any danger to the interests of the United States arising therefrom. The President and the Congress shall determine, in accordance with constitutional processes, appropriate action by the United States in response to any such danger.118

Supplementing the TRA are the “Six Assurances” issued by President Ronald Reagan in a secret July 1982 memo, later publicly released and the subject of hearings held by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in August 1982.119 These assurances were intended to moderate the third Sino–American communiqué, itself generally seen as one of the “Three Communiqués” that form the foundation of U.S.–PRC relations. These assurances of July 14, 1982, were that:

In negotiating the third Joint Communiqué with the PRC, the United States:

- has not agreed to set a date for ending arms sales to Taiwan;

- has not agreed to hold prior consultations with the PRC on arms sales to Taiwan;

- will not play any mediation role between Taipei and Beijing;

- has not agreed to revise the Taiwan Relations Act;

- has not altered its position regarding sovereignty over Taiwan;

- will not exert pressure on Taiwan to negotiate with the PRC.120

Although the United States sells Taiwan a variety of military equipment, provides limited training to Taiwanese military personnel, and sends observers to Taiwan’s major annual exercises, it does not engage in joint exercises with Taiwan’s armed forces. Some Taiwan military officers attend professional military education institutions in the United States, and there are regular high-level meetings between senior U.S. and Taiwan defense officials, both uniformed and civilian.

The United States does not maintain any bases in Taiwan. However, in late 2021, after reports of an uptick in the number of U.S. military advisers in Taiwan, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen acknowledged their presence going back at least to 2008.121 The numbers involved are in the dozens but are likely to increase to between 100 and 200 by the end of 2023 according to media reports.122 Most of these personnel will continue to be focused on training Taiwanese soldiers to use U.S.-sourced military equipment and to carry out military maneuvers with a view to defending Taiwan against a hypothetical attack by China.

Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. On a region-wide basis, the U.S. has two major ongoing defense-related initiatives to expand its relationships and diversify the geographical spread of its forces:

- The Maritime Security Initiative, which is intended to improve the security capacity of U.S. partners, and

- The Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI), which bolsters America’s military presence and makes it more accountable.

Among the most important of the bilateral partnerships in this effort, beyond those listed previously, are Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. None of these relationships is as extensive and formal as America’s relationship with Singapore, India, and U.S. treaty allies, but all are of growing significance.

After decades without diplomatic relations following the Vietnam War, improvements in bilateral relations in recent years have led to Vietnam’s emergence as a nascent U.S. security partner. Relations have been bolstered by U.S. efforts to assist Vietnam in mitigating continued dangers from Vietnam War–era unexploded ordnance (UXO) as well as bilateral efforts to address other war legacy issues. Since 1993, for example, “the U.S. government [has] contributed more than $206 million for UXO efforts,” and “UXO assistance continues to be a foundational element of U.S.–Vietnam relations.”123

Since the normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1995, the U.S. and Vietnam also have gradually normalized their defense relationship, codified in 2011 with a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) Advancing Bilateral Defense Cooperation.124 In 2015, the MOU was updated by the Joint Vision Statement on Defense Cooperation, which includes references to such issues as “defense technology exchange”125 and was implemented under a three-year 2018–2020 Plan of Action for United States–Viet Nam Defense Cooperation that was agreed upon in 2017.126 According to USINDOPACOM’s 2022 command posture statement, the U.S. and Vietnam “are expected to sign a three-year Defense Cooperation Plan of Action for 2022–2024 and an updated Defense MOU Annex codifying new cooperation areas, including defense trade, pilot training, cyber, and personnel accounting (POW/MIA).”127

Significant limits on the U.S.–Vietnam security relationship persist, including a Vietnamese defense establishment that is very cautious in its selection of defense partners; ties between the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) and Chinese Communist Party (CCP); and a Vietnamese foreign policy that seeks to balance relationships with all major powers. The most significant development with respect to security ties over the past several years has been relaxation of the ban on sales of arms to Vietnam. The U.S. lifted the embargo on maritime security–related equipment in the fall of 2014 and then ended the embargo on arms sales completely in 2016. The embargo had long served as a psychological obstacle to Vietnamese cooperation on security issues, but lifting it has not changed the nature of the articles that are likely to be sold.

Transfers to date have been to the Vietnamese Coast Guard. These include provision under the Excess Defense Articles (EDA) program of three decommissioned Hamilton–class cutters and 24 Metal Shark patrol boats as well as infrastructure support.128 Vietnam is scheduled to take delivery of six Insitu129 ScanEagle unmanned aerial system (UAS) drones for its Coast Guard.130 The U.S. is also providing T-6 turboprop trainer aircraft.131 Agreement has yet to be reached with respect to sales of bigger-ticket items like refurbished P-3 maritime patrol aircraft, although they have been discussed.

The U.S.–Vietnam Cooperative Humanitarian and Medical Storage Initiative (CHAMSI) is designed to enhance cooperation on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief by, among other things, prepositioning related American equipment in Da Nang, Vietnam.132 This is a sensitive issue for Vietnam and is not often referenced publicly, but it was emphasized during Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc’s visit to Washington in 2017 and again during Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s visit to Vietnam in 2018. In the same year, Vietnam participated in RIMPAC for the first time. It did not participate in the exercise in 2020, when it was scaled down because of COVID-19,133 or in 2022.

There have been two high-profile port calls to Vietnam since 2018. Early that year, the USS Carl Vinson visited Da Nang with its escort ships in the first port call by a U.S. aircraft carrier since the Vietnam War, and another carrier, USS Theodore Roosevelt, visited Da Nang in March 2020. These are significant signals from Vietnam about its receptivity to partnership with the U.S. military—messages underscored very subtly in Vietnam’s 2019 Viet Nam National Defence white paper.134 In July 2022, a potential third carrier visit, this time by the USS Ronald Reagan, was cancelled.135 The U.S., like others among Vietnam’s security partners, remains officially restricted to one port call a year with an additional one to two calls on Vietnamese bases being negotiable.

The U.S. and Malaysia, despite occasional political differences, “have maintained steady defense cooperation since the 1990s.” Examples of this cooperation have included Malaysian assistance in the reconstruction of Afghanistan and involvement in antipiracy operations “near the Malacca Strait and, as part of the international anti-piracy coalition, off the Horn of Africa” as well as “jungle warfare training at a Malaysian facility, bilateral exercises like Kris Strike, and multilateral exercises like Cobra Gold, which is held in Thailand and involves thousands of personnel from several Asian countries plus the United States.”136 The U.S. has occasionally flown P-3 and/or P-8 patrol aircraft out of Malaysian bases in Borneo.

The U.S. relationship with Malaysia was strengthened under President Barack Obama and continued on a positive trajectory under the Trump Administration. In addition to cooperation on counterterrorism, the U.S. is focused on helping Malaysia to ensure maritime domain awareness. In 2020, then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for South and Southeast Asia Reed B. Werner summarized recent U.S. assistance in this area:

[M]aritime domain awareness is important for Malaysia, given where it sits geographically. Since 2017, we have provided nearly US$200 million (RM853 million) in grant assistance to the Malaysian Armed Forces to enhance maritime domain awareness, and that includes ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), maritime surveillance upgrades, and long-range air defence radar.137

Malaysia has also been upgrading its fleet of fighter aircraft. In February 2023, Malaysia awarded a $920 million contract to Korea Aerospace Industries for 18 FA-50 light attack aircraft, the first of which is to be delivered in 2026.138

The U.S.–Indonesia defense relationship was revived in 2005 following a period of estrangement caused by American concerns about human rights. It now includes regular joint exercises, port calls, and sales of weaponry. Because of their impact on the operating environment in and around Indonesia, as well as the setting of priorities in the U.S.–Indonesia relationship, the U.S. has also worked closely with Indonesia’s defense establishment to reform Indonesia’s strategic defense planning processes.

U.S.–Indonesia military cooperation is governed by the 2010 Framework Arrangement on Cooperative Activities in the Field of Defense and the 2015 Joint Statement on Comprehensive Defense Cooperation139 as well as the 2010 Comprehensive Partnership. These agreements have encompassed “more than 200 bilateral military engagements a year” and cooperation in six areas: “maritime security and domain awareness; defense procurement and joint research and development; peacekeeping operations and training; professionalization; HA/DR [High Availability/Disaster Recovery]; and countering transnational threats such as terrorism and piracy.”140

In 2021, the agreements framed new progress in the relationship that included breaking ground on a new coast guard training base,141 inauguration of a new Strategic Dialogue,142 and the largest-ever U.S.–Indonesia army exercise.143 In 2022, this exercise, Garuda Shield, involved ”more than 4,000 combined forces from 14 countries.”144 As of March 2021, the U.S. “ha[d] $1.88 billion in active government-to-government sales cases with Indonesia under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system.”145 In February 2022, the U.S. agreed to sell Indonesia “up to 36” F-15s and related equipment and munitions worth $14 billion.146 During a visit by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to Jakarta in November 2022, Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto said that Indonesia “is on the verge of making a decision about buying” the jets147 and that the deal was in “advanced stages.”148

The U.S. and Indonesia also have signed two of the four foundational information-sharing agreements that the U.S. maintains with its closest partners: the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) and Communications Interoperability and Security Memorandum of Agreement (CISMOA).

Afghanistan. On October 7, 2001, U.S. forces invaded Afghanistan in response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. This marked the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom to combat al-Qaeda and its Taliban supporters. The U.S., in alliance with the U.K. and the anti-Taliban Afghan Northern Alliance forces, ousted the Taliban from power in December 2001. Most Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders fled across the border into Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas where they regrouped and initiated an insurgency in Afghanistan in 2003 that would endure for 20 years.

In 2018, U.S. Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad initiated talks with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar, in an attempt to find a political solution to the conflict and encourage the group to negotiate with the Afghan government.149 In February 2020, Ambassador Khalilzad and Taliban co-founder and chief negotiator Abdul Ghani Baradar signed a tentative peace agreement in which the Taliban agreed that it would not allow al-Qaeda or any other transnational terrorist group to use Afghan soil.150 It also agreed not to attack U.S. forces as long as they provided and remained committed to a withdrawal timeline, eventually set at May 2021.

In April 2021, President Biden announced that the U.S. would be withdrawing its remaining 2,500 soldiers from Afghanistan by September 11, 2021, remarking that America’s “reasons for remaining in Afghanistan are becoming increasingly unclear.”151 As the final contingent of U.S. forces was leaving Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban launched a rapid offensive across the country, seizing provincial capitals and eventually the national capital, Kabul, in a matter of weeks. During the Taliban offensive, President Ghani fled the country for the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the Afghan security forces largely abandoned their posts.152

Having vacated the Air Force base at Bagram in July, the U.S. and other countries were left trying to evacuate their citizens and allies from the Kabul International Airport as the Taliban assumed control of the capital. Amid the chaos, a suicide bombing attack on the airport perimeter on August 26 killed 13 U.S. military personnel and nearly 200 Afghans. IS-K, the local branch of ISIS, claimed responsibility for the attack, and the Biden Administration subsequently launched drone strikes on two IS-K targets.153

The last U.S. forces were withdrawn on August 30, 2021, and the Taliban soon formed a new government comprised almost entirely of hard-line elements of the Taliban and Haqqani Network, including several individuals on the U.S. government’s Specially Designated Global Terrorists list.154 Sirajuddin Haqqani, arguably the most powerful figure in the new Afghan government, carries a $10 million U.S. bounty for his organization’s involvement in countless terrorist attacks.155

Since seizing power, the Taliban government has hunted down and executed hundreds of former government officials and members of the Afghan security forces. It also has cracked down on Afghanistan’s free press, banned education for girls beyond sixth grade while the daughters of several Taliban leaders attend school in Pakistan and the UAE, and curtailed the rights of women and minorities. Under Taliban rule, the Afghan economy has collapsed. The World Bank estimates that GDP contracted by 30 percent–35 percent between 2021 and 2022,156 and the U.N. World Food Programme has said that Afghanistan is at risk of famine without hundreds of millions of dollars in food aid.157

Like most of the world’s other governments, the U.S. government has refused to offer the new Taliban government diplomatic recognition. In October 2021, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Colin Kahl admitted that both al-Qaeda and ISIS-K (the local branch of the Islamic State) were operating in Afghanistan with the intent to conduct terrorist attacks abroad, including against the U.S. Specifically, Kahl estimated that “[w]e could see ISIS-K generate that capability in somewhere between 6 or 12 months” and that “Al Qaeda would take a year or two to reconstitute that capability.”158

In August 2022, a U.S. drone strike killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman al Zawahari, who was discovered residing in a safehouse in Kabul.159 The U.S. government claimed the operation was the result of “careful, patient and persistent work by counterterrorism professionals” and claimed the Taliban had violated its agreement with the U.S., struck at Doha, in which it pledged not to host al-Qaeda and other international terrorist groups.160

The Taliban–Haqqani government has faced an ongoing wave of attacks, violence, and assassinations from ISIS-K. Since its emergence around 2015, the Islamist extremist group has been competing with the Taliban–Haqqani Network alliance for territory and recruits. Meanwhile, the Pakistani Taliban, allies of the Afghan Taliban and Haqqani Network, have escalated attacks against neighboring Pakistan since the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan.

Pakistan. After decades of tactical collaboration during the Cold War, Pakistan and the U.S. developed an often troubled relationship after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. During the early stages of the war, the U.S. and NATO relied heavily on logistical supply lines running through Pakistan to resupply anti-Taliban coalition forces. Supplies and fuel were carried on transportation routes from the port at Karachi to Afghan–Pakistani border crossing points at Torkham in the Khyber Pass and Chaman in Baluchistan province. For roughly the first decade of the war, approximately 80 percent of U.S. and NATO supplies traveled through Pakistani territory. Those amounts progressively decreased as the U.S. and allied troop presence decreased.

By the late 2000s, tensions emerged in the relationship over accusations by U.S. analysts and officials that Pakistan was providing a safe haven to the Taliban and its allies as they intensified their insurgency in Afghanistan. The Taliban’s leadership council (shura) was located in Quetta, the capital of Pakistan’s Baluchistan province. U.S.–Pakistan relations, already tense, suffered an acrimonious rupture in 2011 when U.S. special forces conducted a raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout in Abbottabad less than a mile from a prominent Pakistani military academy.161 Relations deteriorated further in 2017 when President Trump suspended billions of dollars of U.S. military assistance to Pakistan and declared that “[w]e can no longer be silent about Pakistan’s safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond.”162

Since 2015, U.S. Administrations have refused to certify that Pakistan has met requirements to crack down on the Haqqani Network, an Afghan terrorist group with known links to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency.163 In addition to suspending aid, the Trump Administration supported both Pakistan’s addition to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) list of Jurisdictions Under Increased Monitoring (“grey list”) for failing to fulfill its obligations to prevent the financing of terrorism and its designation as a “Countr[y] of Particular Concern under the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 for having engaged in or tolerated ‘systematic, ongoing, [and] egregious violations of religious freedom.’”164 In October 2022, Pakistan was removed from the grey list because of its reportedly improved efforts against “money laundering, terrorist financing, and…armed groups and individuals.”165

Despite harboring and supporting a variety of known terrorist groups that operate in Afghanistan and Kashmir, Pakistan has been subject to terrorism from anti-state extremist groups, including the Pakistani Taliban (TTP). In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the TTP engaged in a bloody campaign of terrorism against the Pakistani state; from 2008–2013, approximately 2,000 civilians were killed in terrorist attacks each year. The Pakistan military launched a series of operations against these groups in 2014 and succeeded in progressively reducing terrorist violence in the years that followed.166

However, after the Afghan Taliban assumed power in Kabul, the number of attacks on Pakistan civilian and military targets spiked dramatically.167 Islamabad has repeatedly accused the Taliban government in Kabul of harboring the TPP and ISIS-K—the two groups that took credit for most of these attacks—or failing to rein in their activities. Tensions reached a tipping point in April 2022 when the Taliban accused Pakistan of launching cross-border raids into Afghanistan to target these groups and causing dozens of civilian casualties in the process.168 The Pakistani government’s peace negotiations with the TTP have produced a cycle of temporary cease-fires punctuated by cycles of violence and terrorism against civilians and Pakistani security personnel. Pakistan claims the Taliban-led government in Kabul is either collaborating with the Pakistani Taliban or tacitly permitting them to use Afghan soil to launch attacks inside Pakistan.

Pakistan–U.S. relations improved modestly from 2018–2021 as Pakistan involved itself in bringing the Afghan Taliban to the negotiating table in Doha. However, relations have remained generally strained since the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. President Biden reportedly has refused to engage in direct communications with Prime Minister Imran Khan, and Pakistan declined an invitation to attend President Biden’s December 2021 Summit for Democracy. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman visited Pakistan in October 2021 to discuss “the importance of holding the Taliban accountable to the commitments they have made.” Days earlier, she noted: “We don’t see ourselves building a broad relationship with Pakistan. And we have no interest in returning to the days of hyphenated India–Pakistan.”169

Pakistan also has been beset by simultaneous economic, political, and security crises in recent years. Prime Minister Khan was ousted from power in April 2022 after losing a no-confidence vote in parliament and was later barred from running for office for five years based on charges that he insists are politically motivated. Khan’s supporters have repeatedly taken to the streets, and Khan has been calling for new parliamentary elections ever since the 2022 by-elections in which his PTI political party performed well. In May 2023, Khan was arrested on corruption charges, and widespread protests ensued.170 Unusually, protesters targeted military facilities and personnel, even raiding the homes of senior military commanders.171 However, by month’s end, Khan was released, the protests abated, and several members of his political party defected.172 New national elections are due to be held in October 2023.173

Pakistan’s economy is teetering on the verge of collapse with skyrocketing inflation and dwindling foreign exchange reserves. These problems were made even worse by devastating floods in 2022 that killed thousands and affected millions. The Pakistani government is seeking billions of dollars in aid simply to meet its growing debt obligations but has found multilateral lenders like the IMF and traditional patrons like Saudi Arabia and China increasingly unwilling to provide relief on favorable terms. Pakistan has obligations to repay nearly $80 billion in international loans in the next three to four years but has just $3 billion in foreign exchange reserves.174

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Stockpile. In September 2021, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists estimated that Pakistan “now has a nuclear weapons stockpile of approximately 165 warheads.” The report added that “[w]ith several new delivery systems in development, four plutonium production reactors, and an expanding uranium enrichment infrastructure, however, Pakistan’s stockpile…could grow to around 200 warheads by 2025, if the current trend continues.”175

The possibility that terrorists could gain effective access to Pakistani nuclear weapons is contingent on a complex chain of circumstances. Concern about the safety and security of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons increases when India–Pakistan tensions increase. If Pakistan were to move its nuclear assets or (worse) take steps to mate weapons with delivery systems, the likelihood of theft or infiltration by terrorists could increase.

Increased reliance on tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) is of particular concern because launch authorities for TNWs are typically delegated to lower-tier field commanders far from the central authority in Islamabad. Another concern is the possibility that miscalculations could lead to regional nuclear war if India’s leaders were to lose confidence that nuclear weapons in Pakistan are under government control or, conversely, were to assume that they were under Pakistani government control after they ceased to be.