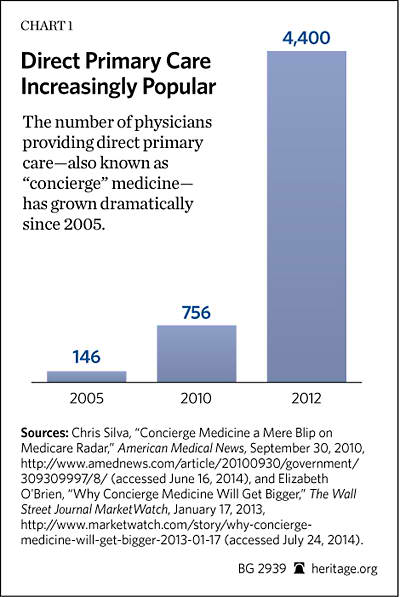

With new concerns over the effects of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)[1] on access to care and continued frustration with third-party reimbursement, innovative care models such as direct primary care may help to provide a satisfying alternative for doctors and patients. Doctors paid directly rather than through the patients’ insurance premiums typically provide patients with same-day visits for as long as an hour and offer managed, coordinated, personalized care. Direct primary care—also known as “retainer medicine” or “concierge medicine”[2]—has grown rapidly in recent years. There are roughly 4,400 direct primary care physicians nationwide,[3] up from 756 in 2010 and a mere 146 in 2005.[4]

Direct primary care could resolve many of the underlying problems facing doctors and patients in government and private-sector third-party payment arrangements. It has the potential to provide better health care for patients, create a positive work environment for physicians, and reduce the growing economic burdens on doctors and patients that are caused by the prevailing trends in health policy. With some specific policy changes at the state and federal levels, this innovative approach to primary care services could restore and revolutionize the doctor–patient relationship while improving the quality of care for patients.

In general, direct primary care practices offer greater access and more personalized care to patients in exchange for direct payments from the patient on a monthly or yearly contract. Physicians can evaluate the needs and wants of their unique patient populations and practice medicine accordingly. Patients relying on a direct primary care practice can generally expect “all primary care services covered, including care management and care coordination … seven-day-a-week, around the clock access to doctors, same-day appointments, office visits of at least 30 minutes, basic tests at no additional charge, and phone and email access to the physician.”[5] Some practices may offer more services, such as free EKGs and/or medications at wholesale cost.

This approach would enable doctors and patients to avoid the bureaucratic complexity, wasteful paperwork and costly claims processing, and growing frustrations with third-party payer systems. It can also cultivate better doctor–patient relationships and reduce the economic burden of health care on patients, doctors, and taxpayers by reducing unnecessary and costly hospital visits.

While the rapid growth in direct primary care is a relatively recent trend, policymakers could help by eliminating barriers to such innovative practices and creating a level playing field for competition. At the state level, policymakers should review and clarify existing laws and regulations, repealing those that impede these arrangements. At the federal level, policymakers should consider facilitating greater access for patients to direct primary care through the federal tax code and also within existing federal entitlement programs.

The Benefits of Direct Primary Care

While direct primary care is not a new development, it has been given new life because of the growing concerns over the impact of the Affordable Care Act on access to care, such as the doctor shortages,[6] narrow networks,[7] and frustrations and failures that doctors and patients have experienced with third-party reimbursement.

Before the rapid growth of employer-based health insurance coverage in the 1940s, Americans paid directly with cash for virtually all of their health care. With the rise of third-party health insurance after World War II, cash payment for medical services declined sharply. Doctors, hospitals, and other medical professionals increasingly were reimbursed through third-party insurance, which often provided “first dollar” coverage. Superficially, this seemed to be efficient, quick, and easy, but it had the unintended consequence of making health care financing largely opaque. This hid the true cost of services, leaving patients with the false impression that their employers paid for their medical expenses, except for the occasional co-pay, deductible, or coinsurance.

This major transition in American health care financing during the 1940s left physicians to seek reimbursement from patients’ insurance companies. Over time, the third-party payment systems in both private health insurance and public programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, have become increasingly complex and costly, less transparent, and more economically inefficient.

In light of these mounting complexities and inefficiencies, increasingly dissatisfied doctors and patients are looking for innovative ways to deliver and receive primary care. Direct primary care has become a viable solution for many Americans.

Professional Decline. For many physicians, the traditional third-party payer model is becoming increasingly unattractive. A survey by the Physicians Foundation found that most doctors are profoundly dissatisfied and believe that their profession is in decline. Among the “very important” reasons that they give for the decline are too much regulation and paperwork (79.2 percent of physicians); loss of clinical autonomy (64.5 percent); lack of compensation for quality (58.6 percent); and erosion of physician–patient relationship (54.4 percent).[8]

In Medicare and Medicaid, these shortcomings are exacerbated by their outdated payment models, which routinely underpay physicians relative to the private sector while increasing regulatory and reporting requirements as a condition for continued participation. The Affordable Care Act has only increased these regulatory burdens.

For a typical physician, “half of each day can be consumed with clerical and administrative tasks, such as completing insurance claims forms, navigating complex coding requirements, and negotiating with insurance companies over prior approvals and payment rates.”[9] The Direct Primary Care Coalition estimates that 40 percent of all primary care revenue goes to claims processing and profit for insurance companies.[10] A typical physician would need 7.4 hours per day to provide all of the preventive care as determined by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.[11] Such time commitment is unfeasible when physicians must spend several hours per day on clerical work. Declining reimbursements have prompted primary care providers to see more patients in an attempt to maintain stable income. This means that each visit is only long enough to address the bare essentials, seldom more.

The lack of meaningful interaction and sufficient time for primary care is eroding the doctor–patient relationship. Patients suffer when doctors must see so many of them. Office schedules are almost always full, and doctors are frequently running behind schedule. Patients can expect to wait weeks or even months for an appointment[12] and then often wait an hour or more after they arrive for their appointments to see the doctor. Once the physician sees them, the patient’s chief complaint will be addressed quickly, and the patient will be sent on his or her way.

Patients may feel that they have received poor care, and many do not receive sufficient preventive screening, understand their pharmaceutical regimen, or secure the appropriate management of their chronic diseases. Thomas Bodenheimer, M.D., writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, says, “The majority of patients with diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic conditions do not receive adequate clinical care, partly because half of all patients leave their office visits without having understood what the physician said.”[13]

These problems are byproducts of an overloaded third-party payment system that often expects a doctor to care for nearly 3,000 patients, even though he or she is not reimbursed appropriately for doing so. This process undermines sound medical practice and compromises the quality of patient care.

Moreover, while insurers and legislators often support reforms that compensate for quality rather than quantity, such as value-based purchasing in hospitals and pay for performance for physicians, it remains to be seen whether these modest payment reforms will change treatment dynamics.

Benefits of Direct Primary Care. Direct primary care can avoid many of these problems for doctors and patients. Since direct primary care practices see fewer patients, the physician can spend more time on each visit, offer same-day appointments, and get to know patients well. The doctor no longer feels a need to run from room to room, seeing patients on a tight schedule, just to maintain stable revenues for the practice.

Under direct primary care arrangements, revenues are predetermined by the monthly fees, allowing doctors to focus entirely on caring for their patients. In return, patients receive increased access to their physicians, more of their physicians’ attention, and the benefits of more preventive, comprehensive, coordinated care.

Patients with chronic diseases could also benefit from direct primary care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognizes that “Chronic diseases and conditions … are among the most common, costly, and preventable of all health problems.”[14] Diabetes is a widespread chronic disease and is projected to become more prevalent as the baby-boomer generation ages.[15] Diabetes can also be managed more effectively through better coordinated, longitudinal, preventive primary care such as that provided by direct primary care practices.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that the economic cost of diabetes totaled $245 billion in 2012 and has found that individuals with uncontrolled diabetes cost “two to eight times more than people with controlled or nonadvanced diabetes.”[16] A study focusing on specific prevention quality indicators[17] estimated that the costs of two preventive conditions (“uncontrolled diabetes without complications” and “short-term complications”) for diabetes ranged between $2.3 billion and $2.8 billion annually. Medicare or Medicaid patients accounted for 49 percent of preventable hospital admissions in this study.[18]

While detailed quantitative analysis of the efficacy of direct primary care is scarce, the limited existing research generally supports the value of direct primary care practices. Researchers writing in the American Journal of Managed Care evaluated the cost-benefit for MD-Value in Prevention (MDVIP), a collective direct primary care group with practices in 43 states and the District of Columbia. For states in which sufficient patient information was available (New York, Florida, Virginia, Arizona, and Nevada), decreases in preventable hospital use resulted in $119.4 million in savings in 2010 alone. Almost all of those savings ($109.2 million) came from Medicare patients.[19] On a per-capita basis, these savings ($2,551 per patient) were greater than the payment for membership in the medical practices (generally $1,500–$1,800 per patient per year).[20]

The five-state study also showed positive health outcomes for these patients. In 2010 (the most recent year of the study), these patients experienced 56 percent fewer non-elective admissions, 49 percent fewer avoidable admissions, and 63 percent fewer non-avoidable admissions than patients of traditional practices. Additionally, members of MDVIP “were readmitted 97%, 95%, and 91% less frequently for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia, respectively.”[21]

A British Medical Journal study of Qliance, another direct primary care group practice, also shows positive results. The study found that Qliance’s patients experienced “35% fewer hospitalizations, 65% fewer emergency department visits, 66% fewer specialist visits, and 82% fewer surgeries than similar populations.”[22]

Affordable direct primary care is more than just an option for the wealthy. In fact, two-thirds of direct primary care practices charge less than $135 per month,[23] and these lower-cost practices account for an increasing proportion of the market. For comparison, cable television is projected to cost an average of $123 per month in 2015.[24] Frequently, the sum of the membership fees and an augmented insurance plan—called a “wraparound” plan because it covers costly care beyond the scope of primary care—is lower than the cost of a comprehensive insurance plan by itself. If the number of practices continues to increase and compete directly for consumers, prices will likely decline further.

Additionally, under the ACA, individuals enrolled in a direct primary care medical home[25] are required only to have insurance that covers what is not covered in the direct primary care program. Section 10104 exempts patients who are enrolled in direct primary care from the individual insurance mandate for primary care services if they have supplementary qualified coverage for other services. Individuals not enrolled in direct primary care are required under the ACA to have insurance that covers primary care.

Barriers to Direct Primary Care

While the direct primary care sector is growing and attracting a larger patient base, it still remains only a small portion of the health care market and is burdened by a number of obstacles. One major problem is the lack of a policy consensus on direct primary care providers, specifically how the state and federal laws and regulations should treat such practices, if at all. Certain legal issues will continue to deter physicians from pursuing direct primary care until they are addressed.

State Obstacles. The first major issue is whether direct primary care providers are acting as “risk bearing entities” when providing care in exchange for a monthly fee—and should thus be licensed and regulated as insurers.[26] Six states (Washington, Maryland, Oregon, West Virginia, Utah, and California) have proposed legislation to address this regulatory issue. The West Virginia legislation established a pilot program for direct pay practices, but it has since expired.[27] A California proposal that would allow retainer practices as part of a “multipronged approach” to health care was introduced in 2012, but it died in that state’s Senate Committee on Health.[28]

Four states have enacted meaningful legislation.[29] In March 2012, Utah enacted a law that simply states that primary care practices are exempt from state insurance regulations.[30] Other states have enacted more comprehensive legislation with additional requirements ranging from limitations on the number of patients[31] to required written disclosures for prospective patients.[32]

The lack of clear state policy causes uncertainty and hesitation for physicians looking to form direct primary care practices. Of course, policies and regulations will vary from state to state, but states should create a more predictable regulatory environment for such arrangements. States can enact laws to clarify that direct primary care practices are either explicitly exempt from insurance regulation (as Utah did) or subject only to some simple, limited standards.

Federal Obstacles. At least three federal obstacles hinder the growth of direct primary care practices.

The ACA. The first is how direct primary care practices work, or can work, within the framework of the ACA and the state and federal health care exchanges. In the ACA’s health insurance exchange rules, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recognized that “direct primary care medical homes are providers, not insurance companies.”[33] While this ruling is substantial, it is far from exhaustive.

That ruling is based on a little-known provision of the ACA that allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services to “permit a qualified health plan to provide coverage through a qualified direct primary care medical home plan that meets criteria established by the Secretary.”[34] To qualify, direct care medical home enrollment must be coupled with a wraparound insurance plan that “meets all requirements that are otherwise applicable.”[35] In essence, the Secretary of Health and Human Services is responsible for setting the criteria that determine which direct primary care plans qualify for the exchanges. However, the secretary has yet to establish the criteria, and HHS has given no indication of when that may happen.

Lack of HHS criteria also hinders insurance companies from creating qualified wraparound plans to put on the exchanges. If insurance companies are uncertain of the criteria for direct care practices, they cannot know which benefits to supply in the wraparound plans.

Currently, only a handful of insurance companies have attempted to embrace direct primary care. Cigna and Michigan Employee Benefits Service (MEBS) have created plans for employers who choose to offer wraparound plans in conjunction with direct primary care.[36] Keiser Group is creating plans that work in conjunction with services of MedLion, a direct primary care group.[37] Even with the rise of these plans, there is no clear timeline for when they might be available on the health care exchanges.

Health Savings Accounts. The second federal obstacle is the treatment of these arrangements under the provisions of the Internal Revenue Code that deal with health savings accounts (HSAs). The statute says that to be eligible for an HSA, an individual cannot be covered under a high-deductible health plan and another health plan “which provides coverage for any benefit which is covered under the high deductible health plan.”[38]

In theory, this restriction could be addressed by combining a high-deductible health plan with coverage for primary care through a direct primary care practice. Even so, there would still be another issue. The statute also specifies that funds in an HSA may not be used to purchase insurance.[39] Consequently, Congress would still need to amend the statute either to exempt payments for direct primary care from this restriction or to specify that such payments do not constitute payments for insurance coverage. Given that Congress included language in the ACA providing for integration of direct primary care with insurance coverage offered through the exchanges, amending the tax code’s HSA provisions in a similar fashion should not be controversial.

Recognizing these inconsistencies, Senator Maria Cantwell (D–WA), Senator Patty Murray (D–WA), and Representative Jim McDermott (D–WA) wrote a letter to IRS Commissioner John Koskinen asking for clarification of the tax code.[40]

Some Members of Congress have already attempted to address these discrepancies in the federal tax treatment of direct care payments. The Family and Retirement Health Investment Act of 2013 (S. 1031), sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch (R–UT), would change the language of the Internal Revenue Code to specify that direct primary care is not to be treated as a health plan or insurance and that “periodic fees paid to a primary care physician” count as qualified medical care.[41] This bill has three cosponsors and has been referred to the Senate Committee on Finance. The House companion bill (H.R. 2194), sponsored by Representative Erik Paulson (R–MN), has been referred to the House Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law.[42] If this bill became law, Americans would have greater financial incentives to enroll in a direct primary care practice.

It is perfectly reasonable that direct primary care fees should qualify as medical expenses payable through HSAs. The fact that they do not is simply an artifact of the inability of the drafters of the HSA statute to anticipate the development of new delivery and payment arrangements such as direct primary care practices.

Medicare Coverage. A third obstacle is the status of payments for direct primary care under Medicare. The central issue is whether or not payment for direct primary care violates Medicare’s current balance billing prohibition, which forbids physicians from charging in excess of allowable rates.[43]

During the George W. Bush Administration, HHS Secretary Tommy G. Thompson responded to congressional inquiries by ruling that physicians are compliant with the law as long as the monthly fees do not contribute toward services already covered by Medicare. Most primary care services are reimbursable under Medicare Part B. Consequently, current Medicare law permits consumer payments to direct primary care providers only for items and services not otherwise covered by the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program.

This restriction makes it very difficult for Medicare patients seeking to engage the services of a Medicare-participating physician directly. The HHS Office of the Inspector General has charged at least one physician with violating the balance billing prohibition.[44] In 2005, the Government Accountability Office reinforced HHS’s official position, saying that direct primary care practices are legal only to the extent that they comply with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations.[45]

Yet many Medicare patients could benefit from enrolling with direct primary care practices. Medicare patients would likely be more inclined to do so if Congress eliminated current barriers and restrictions on their ability to engage the services of a Medicare-participating physician through a direct primary care arrangement. Under current law, a Medicare doctor must formally enter into a private contract with the patient under restrictive terms and conditions set by Medicare and drop out of Medicare, refraining from taking all other Medicare patients for two years. This bizarre statutory restriction does not apply to patients’ direct payment of physicians in any other government program, including Medicaid.[46]

In 2011, Representative Bill Cassidy (R–LA) offered legislation (H.R. 3315) to create a pilot program to reimburse direct primary care medical homes under Medicare. The legislation would have allowed payments of up to $100 per person per month for regular Medicare patients and $125 for dual-eligible patients (those covered by both Medicare and Medicaid) and outlined the scope of services to be provided for reimbursement eligibility.[47] The bill died in committee, but Representative Alan Grayson (D–FL) subsequently encouraged the CMS to develop a similar pilot program using its existing authority.[48]

In the case of Medicaid, current law does not preclude states from paying physicians on a retainer or capitated basis for providing beneficiaries with primary care through a direct primary care practice. Direct primary care practices are very close to the “medical home” concept of primary care delivery for beneficiaries with chronic conditions. States could fund special accounts with debit cards for Medicaid patients, who could use those funds to pay the fees of a direct primary care provider chosen by the beneficiary. As noted, S. 1031 and H.R. 2194 would allow such a Medicaid option.

States pursuing such an approach could potentially reap significant Medicaid savings. The empirical evidence indicates that patients with direct primary care experience substantially lower admissions, fewer emergency room visits, and fewer hospitalizations. If Medicaid patients enjoyed similar experiences, the resulting savings would directly redound to taxpayers. In fact, if the per-capita savings were as substantial as those found in the MDVIP study ($2,551 per person), the savings to taxpayers could exceed the cost of a state Medicaid account program.[49]

Related Issues. Some object that direct primary care would create a two-tiered health care system in which those who cannot afford to pay direct care fees would be priced out of access to quality care.[50] There are several problems with this line of reasoning.

First, it fails to recognize that American health care already is a multitiered system and that the Affordable Care Act is not changing that fact. Indeed, the ACA will likely harden the existing tiers. For example, Medicaid patients already have much more difficulty finding a doctor than those enrolled in private insurance do, and when they find medical care, it is frequently of poorer quality than the care provided to patients in private coverage or Medicare.[51]

Furthermore, a single-tier program, even if it were desirable, would invariably mean that everyone would end up receiving worse, not better, care over time because it would stifle innovation. If innovative clinicians can provide a better option, they should be encouraged, even if it will not immediately be available to all. In a free market, competition will reduce the price of goods and services over time—sometimes rather quickly.

Second, patient cash payments are not necessarily made to physicians in addition to patient payments for an existing comprehensive plan. If a patient opted for a wraparound plan instead of a comprehensive plan, the patient could save money. Currently, 40 cents of every dollar of primary care spending goes to insurance company costs rather than to patient benefits.[52] Eliminating the spending on insurance for routine medical services, which passes through a complex claims processing system, and instead paying the doctor directly would not only cost less, but also empower the patient.

As Dr. Robert Fields, an award-winning direct primary care physician in Maryland, has stated, “Money is not purified by first passing through an insurance company.”[53] As long as the amount of health care spending remains relatively constant or declines, no one is being priced out of health care by direct primary care.

Policymakers in particular should realize that physicians can offer more free care to those who need it most precisely because they have more free time and are spending less time coping with paperwork, claims processing, and the entire set of interactions with health insurance companies that doctors today must endure. Dr. Marcy Zwelling-Aamot, former president of the American Academy of Private Physicians, has noted that “10% of my patients do not pay me one dime. They receive care in exchange for offering their time at a charitable organization in the community.”[54]

Less time spent dealing with third-party payments, whether in the public or the private sector, opens up new opportunities for charity care. Dr. Robert Fields, for example, reports that he can now “volunteer at a community clinic several times a month,” something for which he did not have time before.[55] Doctors want to help their patients. Direct primary care is a way to do so affordably and effectively, not a means of cherry-picking wealthy patients.

Some critics of direct primary care express concern that physicians might abandon their existing patients to start new medical practices. If a physician decides to downsize from 3,000 patients to 600, the situation of the others is a valid concern. The AMA recognized the potential of this problem over a decade ago and established ethical guidelines that require physicians undertaking direct primary care to help former patients find new providers if they do not wish to be part of such a practice.[56] Verifying compliance with such ethical guidelines is difficult, but one University of Chicago survey of direct care physicians notes that “many physicians reported active involvement in transitioning patients to other practitioners…. In addition, most retainer practices are in urban areas that are not as affected by physician shortages as more rural settings.”[57]

Another survey suggests that direct primary care can improve access by “salvaging the careers of frustrated physicians and deferring their decision to leave practice.”[58] For physicians opening direct pay practices straight out of residency or converting from a specialty that does not see patients long term (e.g., emergency room), transferring patients is not even a problem. As long as physicians adhere to the AMA guidelines, there is no ethical concern regarding patient abandonment.

Finally, some argue that the growth in direct primary care will exacerbate the existing national shortage of primary care providers.[59] In essence, if doctors are seeing fewer patients, the nationwide shortage of access to physicians will increase. Yet direct primary care could have the reverse impact. Many of the physicians converting to direct primary care are so frustrated with existing bureaucratic hassles of government and commercial insurance that they might retire if the direct care option is unavailable.

The retirement problem is very real. A survey of over 5,000 physicians by the Doctors Company found that 43 percent of physicians are considering retiring within five years.[60] Contributing factors include declining reimbursements, interference by government and insurance companies, and the growing bureaucratic burdens under the Affordable Care Act.

Mark Smith, president of Merritt Hawkins, says that physicians feel “extremely overtaxed, overrun and overburdened.”[61] Of physicians not retiring, many are seeking research or non-clinical jobs.[62] For example, dropoutclub.com is a new network devoted entirely to helping physicians procure jobs outside of health care. Smith calls this “a silent exodus.”[63] Allowing physicians to practice direct primary care not only addresses the underlying problems facing primary care practice, but also can make primary care appealing once again to more and more physicians, residents, and medical students.

Under the current third-party payment systems, physicians are increasingly overburdened and must see too many patients in too little time. A more important problem is that doctors were never supposed to care for 3,000 patients in the first place. No moral imperative compels physicians to martyr themselves in service to a broken third-party payment system.

Dr. Floyd Russak, a direct primary care internist in Colorado, argues that practicing the current model of “inferior care” is morally wrong when quality care can be provided affordably.[64] Dr. David Albenberg, a family physician in South Carolina, agrees: “What’s ethical about cutting corners and shortchanging patients in the name of efficiency and productivity?”[65] Additionally, Russak proposed that physician’s assistants and nurse practitioners could treat younger, healthier individuals, leaving more experienced physicians to care for older, sicker patients. As a result, all patients could receive comprehensive, quality care at a reasonable cost.

What Policymakers Should Do

Direct primary care could resolve many of the underlying problems facing doctors and patients in government and private-sector third-party payment arrangements. It has the potential to provide better health care for patients, create a positive work environment for physicians, and reduce the growing economic burdens on doctors and patients caused by the prevailing trends in health policy, including implementation of the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

The question is not whether direct primary care should be allowed as part of the health system, but how to enable even more direct primary care practices to flourish. In this, policymakers can play a powerful role.

State Policy Recommendations

State legislators who want to see this innovative approach flourish should implement free-market policies so physicians can feel free to start a direct primary care practice without fear of its being outlawed or overregulated out of existence. Specifically, they should:

- Review, rewrite, or repeal any state law, rule, or regulation that inhibits the growth of direct primary care practices. For example, Maryland limits services in a given year to an annual physical exam, a follow-up visit, and a number of other visits. Such arbitrary restrictions should be removed.[66]

- Address insurance regulation and licensure issues. States that have not done so already should review, and amend as necessary, their laws governing insurance regulation and medical provider licensure so as to ensure that state laws do not create unnecessary impediments to the offering of direct primary care arrangements. In the vast majority of states, physicians remain uncertain about the potential legal complications they could face in operating a direct primary care practice. State lawmakers can easily end that uncertainty, thus enabling physicians to practice with relative confidence and freeing patients from anxiety about the security of their care.

Federal Policy Recommendations

Congress should also make reforms that clarify the status of direct primary care arrangements under the tax code and federal programs. Specifically, Congress should:

- Reform the federal tax code to allow direct primary care payment for services through health savings accounts. The tax code treats direct care membership as a form of insurance, inhibiting individuals from opening HSAs if they are also enrolled in a high-deductible insurance plan. Yet HSAs would be an advantageous way for more consumers to pay direct primary care fees, and Congress should amend the tax code to allow them to pay for direct primary care.

- Establish federal rules allowing medical home services to include direct primary care arrangements. Current law allows direct primary care practices to be treated as medical home services if the practices meet certain requirements. HHS is responsible for setting these requirements but has not yet done so, effectively inhibiting direct primary care.

- Change current law and allow Medicare patients to pay doctors directly outside of the traditional Medicare program. Congress should remove the balanced billing limitations that require physicians to drop out of Medicare for two years if they accept direct payment from Medicare beneficiaries.[67]

- Encourage states to enable Medicaid patients to pay doctors directly for routine medical services. Congress should ensure that states have the flexibility to allow for direct payment in Medicaid, perhaps through establishing Medicaid medical accounts.

Creating a Stable Environment for Direct Care to Flourish

Direct primary care could experience explosive growth, driven by increased awareness, better care, clear legislative intent to foster this mode of care, increasing options for non–primary care fields, and growing discontent among patients and physicians with the current third-party payment system.

Many physicians and patients are discontented, and they will search for other options. Physician discontent is reflected in a recent finding that 90 percent of physicians are unwilling to recommend health care to others as a profession.[68] Patients are equally disappointed with the current system. A 2014 Merritt Hawkins survey found that the average wait time to see a family physician is 19.5 days.[69] After that wait, the average patient will actually be seen for only 7.7 minutes.[70] Discontent on both sides will likely grow, driving doctors and patients to seek alternatives. Direct primary care is one such alternative.

The sheer increase in the number of such practices—nearly 5,500 nationwide—means that more people will likely learn about them from friends, family, and colleagues. As more research about the effectiveness of these practices is published, even more people will learn about them.

Amending federal law could clear the way for further expansion of direct primary care. Given that the ACA already took a small step in that direction, it is possible that such changes could attract bipartisan support in Congress. In particular, legislation to clarify the tax status of direct primary care payment, as well as provisions to allow Medicare and Medicaid patients to enroll in these practices, could accelerate expansion. The rapidly growing Medicare patient population opens up new opportunities for these practices. Because baby boomers will likely have one or more chronic conditions, they would benefit the most from close management under direct primary care.[71]

Primary care physicians are the main practitioners in direct care programs. While non–primary care providers are still a small fraction of direct care providers, they do exist, and they have tremendous potential to expand. For example, White Glove Health, a group of nurse practitioners overseen by doctors, is responsible for the care of nearly half a million patients.[72] Pediatricians, cardiologists, and other specialists are also branching out into direct care models of practice.[73]

The possibilities are endless. Instead of paying higher and higher premiums and deductibles, patients could substitute a simple monthly payment. Doctors and other health care professionals could group together under the direct pay format. While insurance premiums could guarantee catastrophic protection, which is what insurance is meant to do, patients could receive a majority of their care, including specialty care, as part of a monthly fee. If policymakers will encourage change, innovation, and competition instead of just reacting to the increasingly dysfunctional status quo, the sky is the limit.

—Daniel McCorry is a Graduate Fellow in the Center for Health Policy Studies, of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.