School had never been easy for 12-year-old Elias Hines. The sixth grader, who lives in Arizona, is autistic. When he was in first grade, his mother, Holland Hines, went to his classroom and found him under his desk, hands over his ears, rocking back and forth.

Today, he can sit for one to two hours at a time, focused and learning.

During his first few years in the traditional public school system, Elias was bounced around between special needs programs. He had a mixture of great and “not so great” teachers, his mother says.

“I didn’t see a lot of education happening,” Hines says of the first-grade classroom. “I saw damage control. That’s when I decided I needed to do something.”

Not very many private schools had the resources or programming to help Elias, and the ones that did, Hines says, were “astronomically expensive,” costing as much as $30,000 per year. She pulled Elias out of school and started homeschooling him, but soon found out about Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Program. Elias was accepted into the program, which is one of a handful of education savings account programs in the country. Once a part of the ESA, Hines began to receive 90 percent of the funding that would go to a public school on Elias’s behalf in a bank account from which she could spend on education for her son.

“I had the benefit of being able to help decide what kind of school environment would be good for him, what therapies he needed,” says Hines. “It was so liberating. For the first time since he received his autism diagnosis, I had hope. I can execute what will be right for my son. I don’t have to go through a bunch of bureaucracy.”

Implemented in 2011, Arizona’s Education Savings Account law was the first of its kind. For students accepted into the program, the state department of education deposits 90 percent of the funds the state would have allocated to a public school on the child’s behalf into a private bank account. Parents can then use that money on a number of things, including tuition and fees at a private or online school, educational therapies or services, tutoring services, curriculum, testing fees, tuition and fees at an eligible post-secondary education institution, or to pay for bank fees charged for ESA management.

In early April, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signed a bill expanding the program, making every public school student in the state eligible. The bill is the latest in an ever-changing movement across the country to expand school choice at the state level.

Arizona Senate Bill 1431 changed the Empowerment Scholarship Account program, phasing in eligibility by grade over the course of four years. Previously, the program was open only to certain students, like those with special needs, those from failing schools, active duty military families, those adopted from the state foster care system, or Native American students living on reservations.

It was so liberating. For the first time since he received his autism diagnosis, I had hope. I can execute what will be right for my son. I don’t have to go through a bunch of bureaucracy.

A 2013 study published by the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice (known as EdChoice) found 71 percent of parents using ESAs in Arizona were “very satisfied” with the accounts. By contrast, only 21 percent were “very satisfied” with the school or program their child attended the year before joining the program. After using ESAs, no parent responded as “neutral” or any level of dissatisfied, while 30 percent were “very unsatisfied” before the switch.

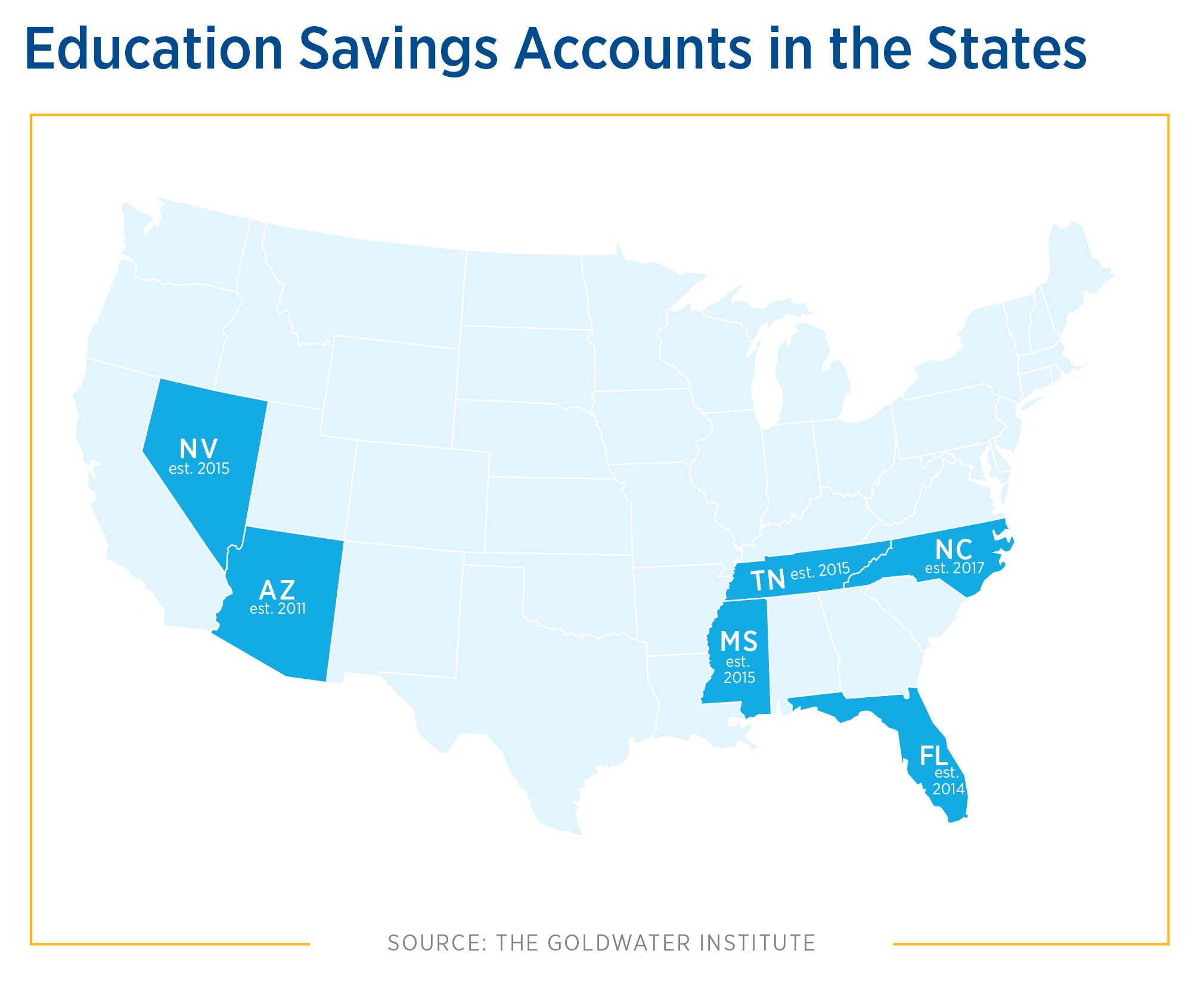

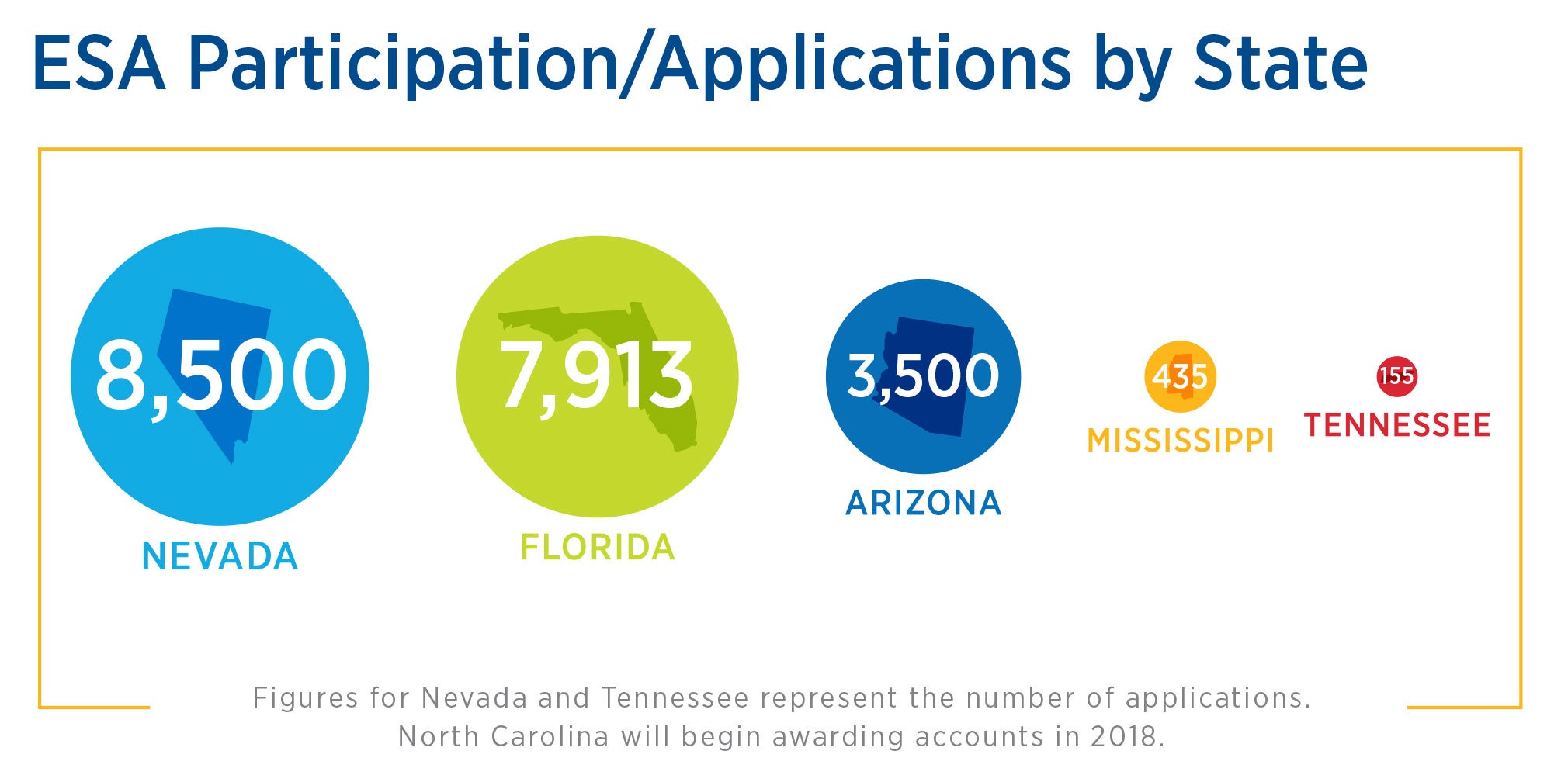

Variations of the education savings account currently exist in three other states: Florida, Tennessee, and Mississippi. Nevada also created an ESA program, but the program is on hold there. In late 2016, the Nevada Supreme Court ruled that the law’s funding mechanism is unconstitutional because it did not have its own funding source and drew from money allocated for public schools.

The programs in Florida, Tennessee, and Mississippi are currently available only to students with disabilities.

(credit: ISTOCKPHOTO)

ESAs are the brainchild of the Goldwater Institute, a free-market think tank in Arizona. Jonathan Butcher, then Goldwater’s education director and one of the authors of the 2013 EdChoice report, was instrumental in creating Arizona’s program six years ago. Butcher, now a policy analyst with The Heritage Foundation, says the recent program expansion shows ESAs work.

“We’ve learned from experience, and the program shows that there will be demand from families. All kinds of families should have access to ESAs,” says Butcher. “Families want this, and as long as students are using it and being successful, I hope we’d continue to give access to it.”

One reason ESAs are so attractive, says Butcher, is that parents can pay for the specific kind of education they want for their child, including how and where they learn.

Tax-credit scholarship and voucher programs are more common forms of school choice, but in both of those program designs the state pays a private school tuition on behalf of a parent. With ESAs, parents receive and control the money themselves, so the state isn’t directly paying for private school. That difference in design can matter in court.

Many states have constitutional prohibitions against the use of public money for private or religious education, often known as Blaine Amendments. Critics of school choice have succeeded in stopping some tax credit and voucher programs with lawsuits that allege violations of those constitutional provisions. However, they have had less success in making the same arguments against ESAs.

Not long after ESAs were first approved in Arizona, for example, several groups, including the Arizona Education Association, filed a lawsuit to stop the program from moving forward. The case eventually made its way to the Arizona Court of Appeals, which ruled in October 2013 that the accounts are constitutional.

“The ESA does not result in the appropriation of public money to encourage the preference of one religion over another, or religion per se over no religion,” wrote Judge Jon W. Thompson. “The parents are given numerous ways in which they can educate their children suited to the needs of each child with no preference given to religious or nonreligious schools or programs.”

The Arizona Supreme Court declined to review the case in 2014, allowing the appeals court ruling to stand.

Butcher says a dozen or more states have considered education savings account plans in recent years, with a handful of state legislatures currently looking at proposals.

The EdChoice report (“Schooling Satisfaction: Arizona Parents’ Opinions on Using Education Savings Accounts”) found the majority of families (65 percent) receiving funds through the Empowerment Scholarship program use at least some of the money to pay for tuition at a private school, like Hines does for her son Elias. Additionally, 41 percent use the money for education therapies, 33 percent for homeschooling curriculum, and 33 percent to hire a tutor.

Within these broad categories, parents reported using the funds for things like special science classes, braille and assistive technology, speech therapy, swimming therapy, and an aide or paraprofessional who can assist students who have special needs with their schoolwork.

Typically, parents participating in the program receive anywhere from $5,000 to $18,000 annually, with the higher amounts going to parents of children with special needs, according to data compiled by the Arizona Department of Education. Just more than 2,000 students participated in fiscal year 2016, and the state estimates 3,500 students will participate in fiscal year 2017.

A fiscal report by the Arizona legislature estimates that ESAs save the state $1,400 for every disabled student who formally attended a traditional public school and now participates in the ESA program.

Butcher says about half of Arizona’s current ESA participants are students with special education needs.

Hines is a prime example. When people ask her if it is difficult to have a child with autism, Hines says she tells them: “It is really hard, but it is infinitely more difficult working with the school system.”

Elias now attends AZ Aspire Academy. The school is suited for students with special needs. It boasts a one-to-one teacher-to-student ratio, according to Founder Sonia Gonzales.

(credit: ISTOCKPHOTO)

About 50 percent of the school’s 120 students (spread across three campuses) use education savings accounts to help pay for tuition, Gonzales says. What started with just one small school has blossomed into three locations with two more planned, Gonzales said.

“The growth that we’ve had has absolutely had to do with the ESAs,” she says.

The growth of ESAs shows that parents want to be involved in their children’s education, according to Gonzales.

Parents reported using ESA funds for things like special science classes, braille and assistive technology, speech therapy, swimming therapy, and an aide or paraprofessional who can assist students who have special needs with their schoolwork.

“I think it’s a direct response to parents knowing their children best and knowing their academic needs,” she says. “We are definitely seeing incredible results. When there is collaboration, we see a lot of growth [in students], socially and emotionally.”

Parents at AZ Aspire Academy help set goals and choose curricula for their children, though the school does use the Common Core for core academic classes. It also offers Advanced Placement courses. The flexibility and parent involvement the school allows are key to helping students with special needs succeed, Gonzales says. She is also the parent of a special needs child and worked in public school administration before opening AZ Aspire Academy.

“I have a lot of hope for public education, but it doesn’t meet the needs of every child,” she says.

Hines says her son Elias now does two hours of concentrated academic work per day with his own teacher, and also has the chance to work with a behavior coach, something that became necessary as Elias grew, and that wasn’t easily available through the public school system.

“It’s the first place he’s been successful,” she says, noting she started to see changes in Elias’ learning and behaviors immediately.

Prior to being able to attend AZ Aspire, she says, Elias could sit to learn for only 10 to 15 minutes at a time, instead of one to two hours. He used to come home from school stressed out and unwilling to discuss his day. Now, he eagerly talks about what he’s learned and is inquisitive about the world around him. He makes mostly A grades and his standardized test scores have also improved. But, most importantly, Hines says her son now enjoys learning.

HOLLAND HINES has used Education Savings Accounts to give her son Elias a new outlook on learning. (credit: GOLDWATER INSTITUTE/ASKAMOMAZ.COM)

“Instead of a fear and loathing for all things academic, he now has the one thing above all else that school is supposed to provide: a love of learning itself,” Hines says. “For my son, the system all but demolished his spirit as well as his ability to take in and commit to memory the information they were trying to teach. Now, he understands the value of learning and is excited about it in every aspect of his life.”

She says the Empowerment Scholarship and the ability for her to make choices about her son’s education, like finding and being able to afford the program at AZ Aspire Academy, has been “absolutely life changing.”

Hines says she thinks education savings accounts can help bridge the gap between what a child needs and what a school can offer.

“So much damage can be done when we don’t put the child first and we put the institution of education before the needs of the child,” she says. “That is something that’s gotten completely turned around.”

Ms. Servold is a freelance writer and the Assistant Director of the Dow Journalism Program at Hillsdale College in Michigan.