America has continued the heated debate as to what must be done to adequately protect our children at schools.

Some (mistakenly) just say “ban guns,” or at least the ones they don’t like. Others (I am afraid equally mistakenly) say just put more guns into schools.

The answer is more complex, however, and will take more effort than either of these camps seem to understand.

Rather than spend time debunking either of these simplistic solutions—neither of which would work—I want to lay out four steps that if applied seriously would actually increase security in schools, and decrease the likelihood that more children will be harmed.

These four interconnected steps are: pre-emptive response, controlling access to school facilities, securing classrooms, and responding on-site to incidents.

1. Pre-emptive Response

In this day of social media, where a generation of young people lives in a state of communication that is near-constant, it is easier than ever to identify warning signs for school shooters and report them to officials.

In almost all of the school shootings that took place—and many that were stopped—clear warning signs emerged before shooting occurred. These warnings must prompt action.

The majority of school shooters have had some kind of mental health problem or social interaction issue that people noticed. The Parkland shooter was flagged multiple times, yet no one took action.

This lack of action was egregious, but not too unusual.

Police and school officials must respond to the red flags that appear on social media or through conversations that troubled youth have.

This response must be immediate and highly public. That way law enforcement can stop the threats that are known, and deter threats that are unknown. Officials must respect the legal procedures of due process, but nonetheless, action must be taken before shots are fired if at all possible.

2. Controlling Access to School Facilities

If a person does not belong in the school, or is attempting to bring in prohibited items such as weapons, they must be denied access.

Schools must have limited points of entry (one, or at most two) that are monitored and controlled by school personnel who can turn people away when needed. School personnel and students should not be able to “cheat” by opening doors for friends or parents or even strangers. Allowing people to enter without authorization, even just to be “nice,” is a huge point of vulnerability. No provision should be made for laziness or convenience.

If a shooter cannot get into a school, he is much less likely to do harm. The issue of access is particularly critical at the beginning and end of the school day, but also throughout the day. When a shooting takes place, a key question is always, “How did the shooter get in?”

3. Securing Classrooms

Next, we must do a better job of securing classrooms inside the school.

Classrooms are often the teacher’s choice for sheltering in place, particularly for the youngest kids who are very difficult to move around quickly. All classroom doors have windows to allow observation (and protection for the children), but in an active shooter situation, this becomes a liability. We need to develop a low-cost, fast way to block that observation point.

Likewise, the doors must be lockable from the inside by the door’s organic lock, and we must provide some sort of simple, quickly applicable blocking mechanism as well. Within the classroom, teachers should have the resources to provide both cover from gunfire and concealment (a general hiding place).

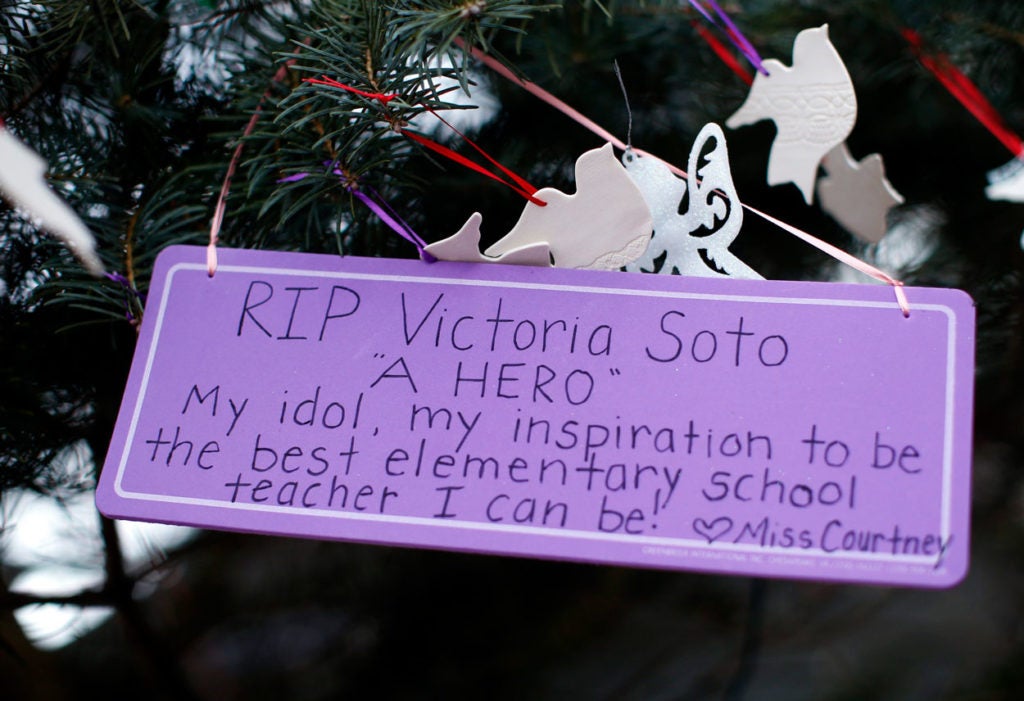

The courageous teacher at Sandy Hook who hid her young pupils in storage cabinets and then faced the gunman ended up giving her life, but her quick thinking saved the lives of her children.

Victoria Soto, the teacher at Sandy Hook Elementary School who hid her students from the shooter, was 27 years old. (Photo: Mike Segar/Reuters/Newscom)

There are now bulletproof sanctuaries that can be put inside classrooms and double as “story corners.” While these may be beyond the budgets of most schools, we must think creatively and plan ahead to devise the best cover and concealment possible.

As a last resort, teachers and older kids should determine how they might actually fight an attacker with improvised weapons available in the class.

4. On-Site Response

Finally, schools must be equipped with the ability to confront and stop an active shooter on-site. Law enforcement will do their best to respond in a timely manner, but they will quite often fail to arrive in time.

Most active shooter scenarios are done in three to six minutes. Few, if any law, enforcement personnel can promise to respond that quickly, especially in nonurban areas.

This is clearly the most contentious aspect of school security, but schools have a binary choice: either they have a dedicated police or security presence on campus, or they must have armed staff and/or faculty. Schools have a menu of options for providing this on-site capability, and communities must choose what they can support, budget-wise and within their collective moral structures.

This is more than just handing out pistols to teachers or asking those with concealed carry permits to bring their weapons to work. Schools must abide by all the proper protocols for storing weapons, conduct psychological evaluations on those who volunteer, and put on extensive training programs.

The training must include negotiation and de-escalation skills, nonlethal control techniques, team response drills, and yes, firearms training. This bears emphasis. The firearms training must be far more than shooting a few dozen rounds at a local range. Shooting in close proximity to other personnel is the most difficult gun skill to learn—it must be trained and drilled until it becomes an engrained skill if we are going to depend on a staff-based response capability.

These four steps will not guarantee 100 percent safety in our schools, but they will materially enhance school security by deterring shooters, defending students, and equipping faculty and administrators to end the killing as quickly as possible.

These are no pie-in-the sky solutions. These workable policies are already being applied is hundreds of schools across America. It is time to apply them in every school.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal