Over 60 years after its release, the Moynihan report remains the most consequential—and controversial—analysis of the black family in American history. One explanation for its continued relevance is how accurately it predicted the breakdown of the traditional family structure. While the report was focused on the “Negro family” at the time, the issues it raised related to the relationship dynamics between men and women, welfare, employment, education, and urbanization help explain why American families of every background look drastically different today than they did decades ago. As the saying goes, however, “when America catches a cold, black America gets pneumonia.” This is one reason I wrote Moving Beyond Moynihan: A New Blueprint to Revive Marriage and Rebuild the Black Family.

The evidence…is that the Negro family in the urban ghettos is crumbling. A middle-class group has managed to save itself, but for vast numbers of the unskilled, poorly educated city working class the fabric of conventional social relationships has all but disintegrated…So long as this situation persists, the cycle of poverty and disadvantage will continue to repeat itself.”“

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (also known as the Moynihan report), 1965

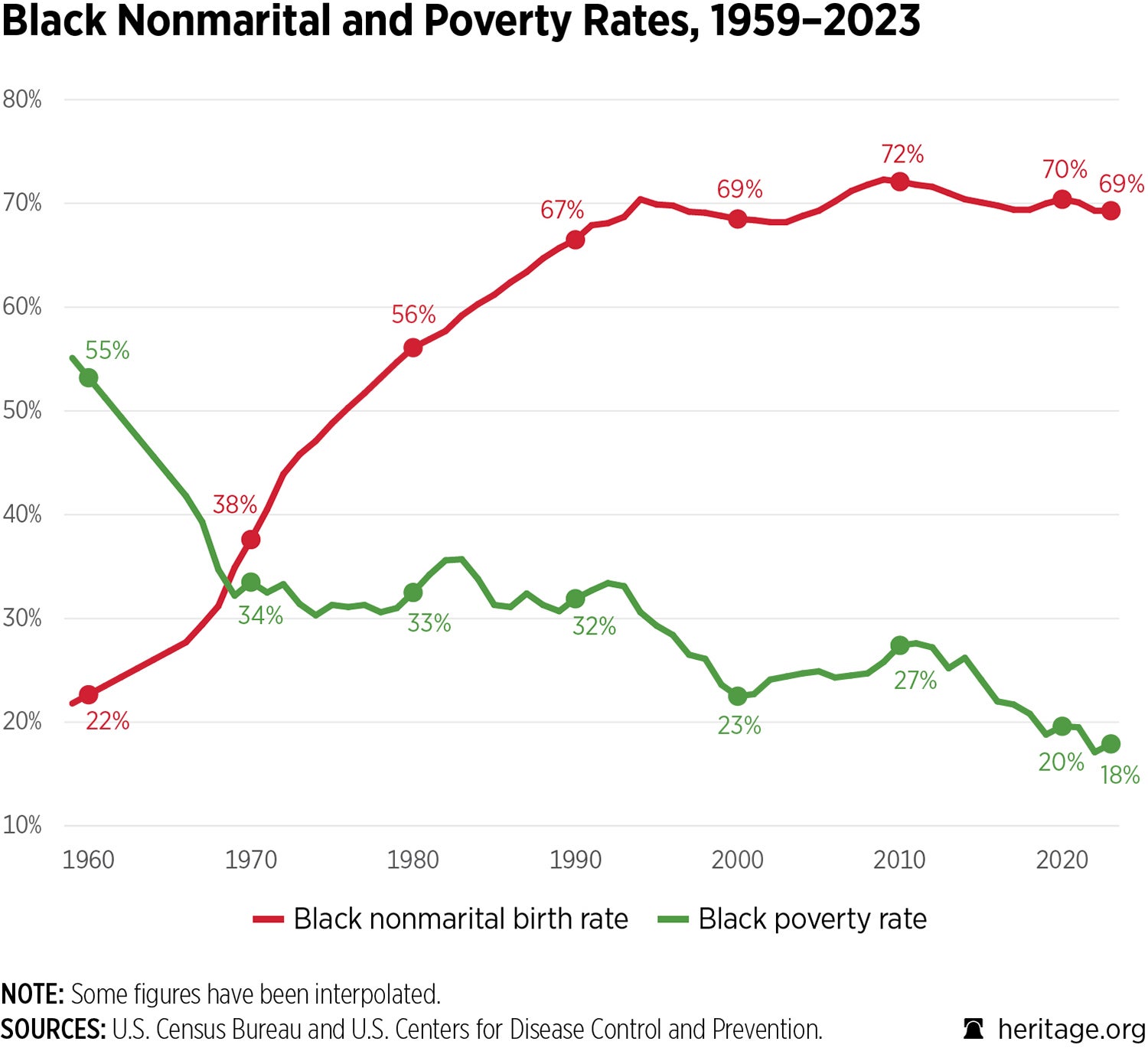

One important contribution of the Moynihan report is its placement in the historical arc of the black family. The development of the black family as a unique, identifiable institution can be seen in four overlapping eras that span 400 years of American history. Moynihan addressed the legacy of slavery in his report, a little more than a century after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. His report, however, came before the rapid expansion of the welfare state. Moynihan also could not have predicted the impact of the second-wave feminist movement and sexual revolution on changing attitudes about sex, marriage, family, and gender roles. He certainly could not foresee the one-in-four nonmarital birth rate that spurred him to write his report in 1965 would rise to 70% by the 1990s.

The reality is the black family is more fractured today than in 1965, despite gains in civil rights, education, economic power, and political representation. In 1959, the poverty rate for blacks was about 55%. Despite those challenging economic circumstances, more than 75% of black children were born to married parents. By 2023, the poverty rate decreased to 18%, but the non-marital birth rate increased to 69%.

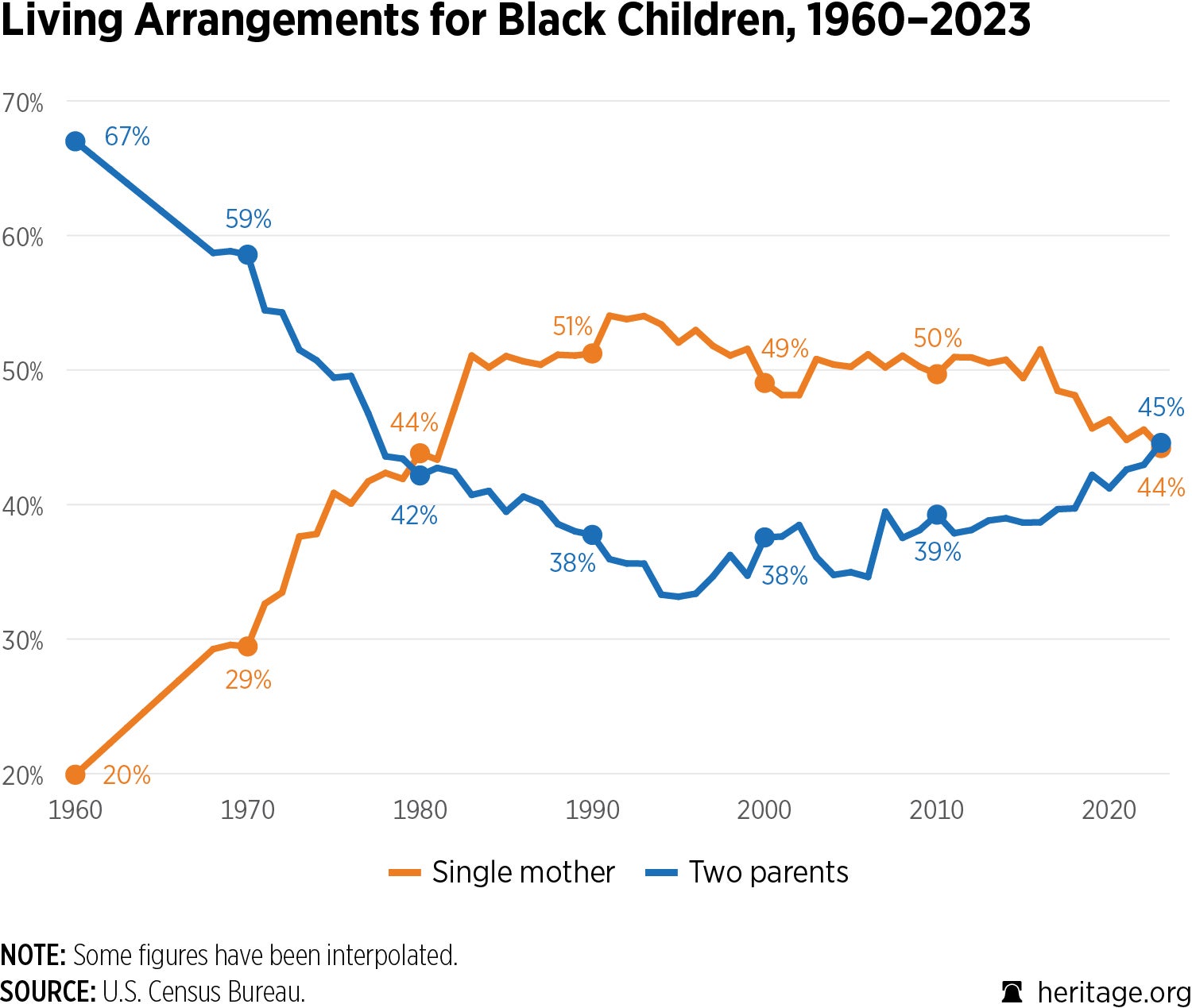

Likewise, according to the 1960 Census, two-thirds of black children lived in two-parent homes. Today, 44% of all black children are being raised by a single mother.

That means in just three generations, a black child who is born to — and raised by — married parents went from being the norm to the exception.

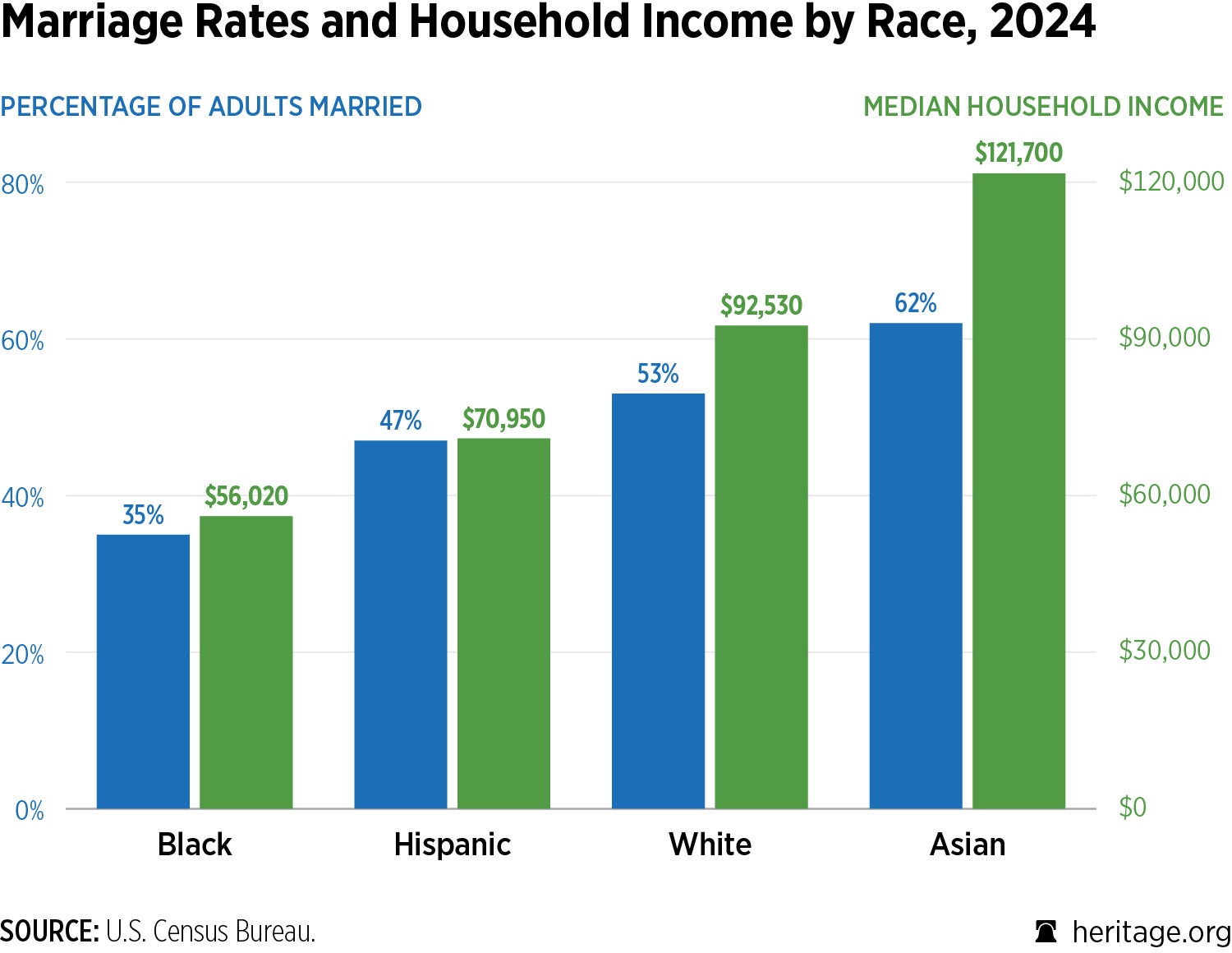

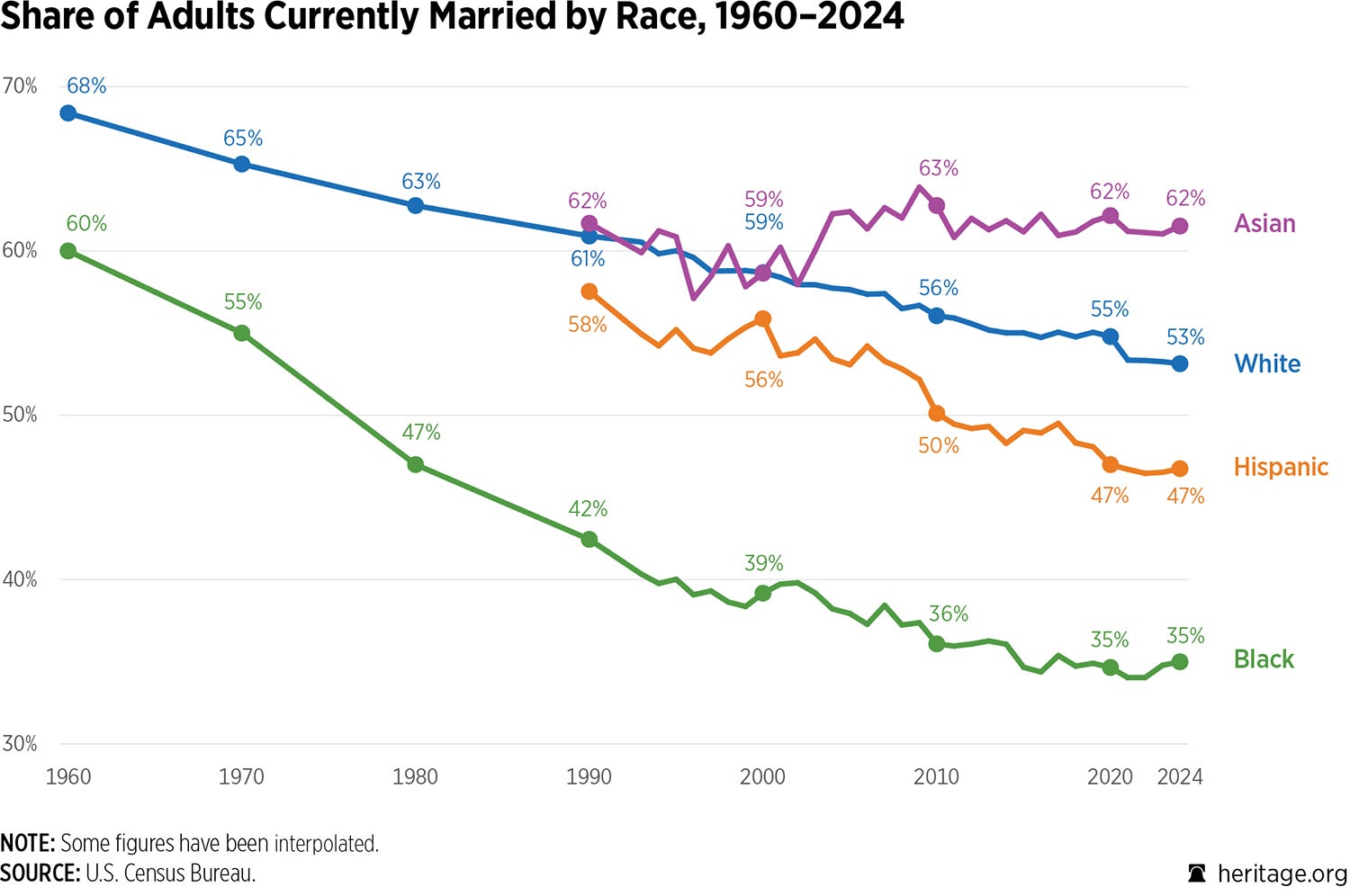

These findings present a “poverty paradox” for those who believe the fracturing of the family is mainly driven by economic factors. They should also prompt civil rights organizations, policymakers, and social commentators to ask a simple question: “If life has generally gotten better for blacks in America since 1965, why have marriage rates decreased and families become more fragile?” An honest attempt to answer that question would note the connection between “marriage inequality” and socioeconomic outcomes. For instance, median household income figures by race follow the same order as marriage rates.

Among American adults, 62% of Asians, 53% of whites, 47% of Hispanics, and 35% of blacks are married. It is no surprise then that Asians have the highest earnings ($121,700), followed by whites ($92,530), Hispanics ($70,950), and then blacks ($56,020). The median income for black married couples ($110,900), however, is higher than the overall household incomes for all groups except Asian Americans.

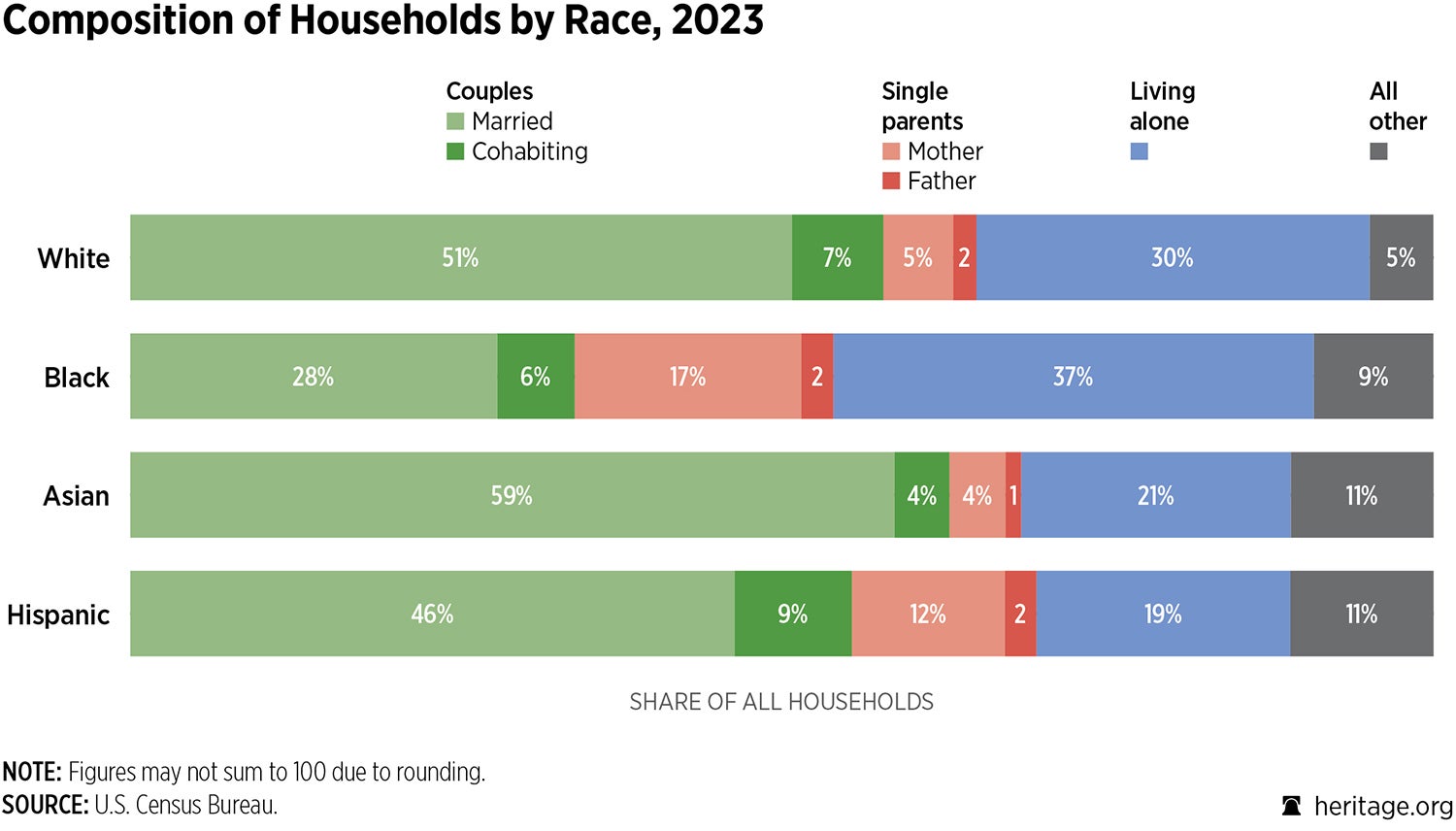

Black married couples under the age of 65 bring in an extra $11,000 per year. By contrast, the median household income for unmarried black women is $50,720. The connection between family structure and financial security is encouraging, but unfortunately married couples only constitute 28% of all black households, compared to a national average of 47%.

The benefits that strong families, built on the foundation of marriage, provide for children extend beyond financial security. Children living with their married birth parents also earn better grades and are less likely to be suspended or expelled than those in single-parent homes. Likewise, married parents are less likely to be contacted about disruptive behavior and their children are less likely to be held back. One study of families in Virginia found 90% of black students from intact families received A’s and B’s in school, compared to 41% of their counterparts in father-absent families. Children in nuclear families also enroll in college at higher rates and have lower incarceration rates as adults. Adolescent girls with present and involved fathers are likewise less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors and become teenage mothers.

There’s no more important ingredient for success, nothing that would be more important for us reducing violence than strong, stable families -- which means we should do more to promote marriage and encourage fatherhood.”“

President Barack Obama speaking on economic opportunity in Chicago in 2013

Decades of research prove what most people already know: children raised in homes with their married biological parents have better outcomes on a range of measures than children raised in other family arrangements, particularly single-parent homes. These outcomes extend beyond test scores and college degrees. An increase in the number of intact families means more children will grow up with the security that comes when parents love one another and create a home environment marked by affection and stability. Even the way children think about family changes based on structure. The family name, family home, family car, family vacations, family tree, and family reunions will all mean something very different in the future or cease to have any meaning at all if the status quo remains unchallenged.

A world in which every black child was raised in a loving household with a married mom and dad would do far more to advance racial uplift than any new government program. When the political left periodically acknowledges the breakdown of the family, it most commonly blames the current situation on the legacy of slavery and mass incarceration. Others will point to deindustrialization and redlining. While these views are understandable, they miss the true nature of the issue. Every trend related to marriage and the family involves at least one of three fundamental elements: men, women, and the institution of marriage. Any analysis of the rise in fractured families—regardless of race—must deal with fundamental changes to at least one of those three.

Welfare is like a super-sexist marriage. You trade in a man for the man. But you can't divorce him if he treats you bad.”“

Johnnie Tillmon, Ms. Magazine, 1972

For example, economic instability can explain why a man feels unprepared to start a family, but it does not explain why he would have a child—or multiple children—with a woman he refuses to marry. There is also a bipartisan assumption that low-income single mothers lack “marriageable” mates. This idea presumes there are traits that make a man a suitable father to a child, yet unqualified to be a woman’s husband.

The truth is major changes in public policy and social norms led to declining marriage rates that have radically reshaped black family life.

The traditional family structure became less prevalent as nonmarital births and single-mother households became more common, a pattern that has replicated itself over decades. Today, there are few institutions in black America that consistently promote the idea men and women should marry before having children and that the intact families provide the best outcomes for everyone in the home.

It was drummed into me that being a mother, raising children and running a home were a form of slavery. Having a career, travelling the world and being independent were what really mattered according to her.”“

Rebecca Walker, on the influence of her mother, feminist icon Alice Walker, 2008

Put simply, the black family is in a state of emergency and there are only two choices about how to respond. The first is to accept the disappearance of marriage and two-parent homes as the norm, both now and in the future. This path will consign more black children to lives of poverty and all the negative social and emotional outcomes that come with family breakdown. The second is to marshal the resources and capital needed for reconstruction. This path has the potential to restore and revitalize communities because it acknowledges that the only way for black America to thrive in future generations is to rebuild the family, an intergenerational reconstruction project that can only be successful with a cultural commitment to reviving the institution of marriage.

The Blueprint for Black Family Revival

-

Make marriage revival and family restoration a priority for black leaders. Black leaders in religion, politics, media, academia, industry, and entertainment must use their influence to address the decline of the family.

-

Reframe family strengthening efforts to focus on the rights of children. Family restoration should be seen as an important civil rights issue driven by two truths. The first is that all children have a right to the affection and protection of the man and woman who created them. The second is that the ideal environment for this right to be exercised is in a loving and stable home with their married biological parents.

-

Harness the power of key institutions to create a culture of marriage. Black churches, HBCUs, media outlets, and federal, state, and local government all have a role to play in encouraging men and women to marry each other before having children as well as discouraging adults from ignoring the ideal sequence for forming a family.

-

Anticipate resistance from “allies.” Efforts to revive marriage and rebuild the traditional family will be opposed by different parts of the progressive political coalition, including feminist and LGBT activists. Resistance will also come from liberals who believe child outcomes are more dependent on social welfare spending than family structure.

You cannot have a strong, thriving nation without strong communities. You cannot have strong communities without strong families. And you cannot have strong families without strong marriages. That is why a new plan is needed to solve an old problem. Moving Beyond Moynihan: A New Blueprint to Revive Marriage and Rebuild the Black Family addresses the major changes in social norms and public policy since the 1960s that influence family dynamics today.