—Chief Justice William Rehnquist, October 6, 20001

Life

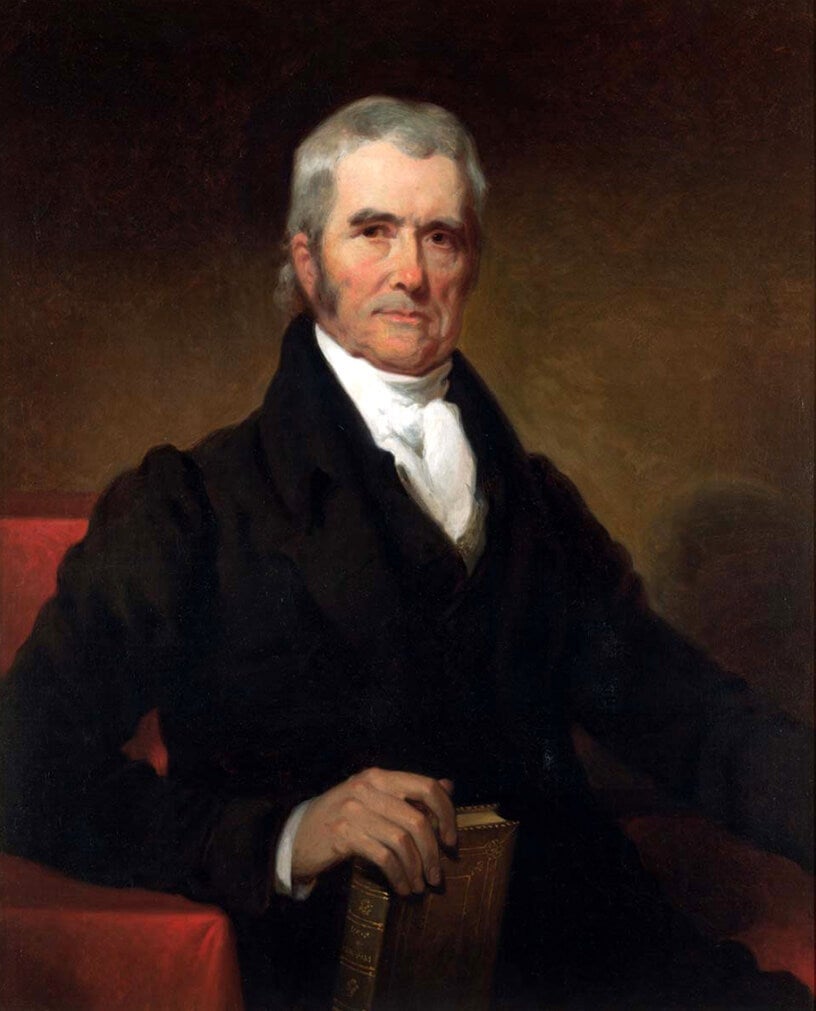

John Marshall was born on September 24, 1755, in Germantown, Virginia, the eldest of 15 children born to Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith. He married Mary Willis “Polly” Ambler on January 3, 1783, at the age of 27. They had 10 children, six of whom lived to adulthood. He died in Philadelphia on July 6, 1835, and is buried next to his wife in the Shockoe Hill Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. Marshall, often referred to as the Great Chief Justice, remains the longest-serving Chief Justice of the United States in American history. During that time, he participated in more than 1,000 decisions and wrote more than 500 majority opinions. After his passing, Justice Joseph Story said of Marshall, “His proudest epitaph may be written in a single line—‘Here lies the expounder of the Constitution.’”

Education

Marshall received most of his early education at home, supplemented by instruction from a clergyman and a one-year stint at an academy in Westmoreland County; he studied law at the College of William & Mary and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1780.

Religion

Although Marshall’s convictions were Unitarian, he attended a more popular Episcopalian church out of deference to his wife.

Political Affiliation

Federalist

Highlights and Accomplishments

1782–1789: Virginia House of Delegates

1785–1788: Recorder of the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond

1795–1796: Virginia House of Delegates

1799–1800: United States House of Representatives

1800–1801: Secretary of State

1801–1835: Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Life of John Marshall

John Marshall began life in a log cabin close to the American frontier. His father, Thomas, came from a notable Virginia landowning family, and the elder Marshall would spend several years in local and state government. He became a prominent surveyor who befriended and frequently worked with George Washington, also a prominent surveyor and who would later play a significant role in Marshall’s own life. His mother, Mary, was the daughter of an Anglican minister and a descendant of the influential Randolph family, which would make the younger Marshall a distant cousin of Thomas Jefferson. Marshall and Jefferson disliked each other, at times intensely. Some have speculated that one of the reasons for this tension was that Marshall’s grandmother had been disowned by the wealthy Randolph family while Jefferson’s ancestors stayed in good standing, although there are no writings that suggest this was the cause of their frosty relationship (they had many other reasons not to like each other).

Marshall was the eldest of 15, and his parents took it upon themselves to educate him themselves with supplemental instruction from a clergyman and a one-year stint at an academy in Westmoreland County where he befriended future President James Monroe. The family was well-equipped for the task. The elder Marshall’s library included the works of Horace, Livy, Alexander Pope, John Dryden, John Milton, and William Shakespeare. As an adult, Marshall would recall fondly how his father instructed him to transcribe the poems of Pope. Among the books in that library was a copy of Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Marshall would later write that from the time he was a young boy, “I was destined to the bar” (a similar destiny awaited four of his six brothers).

During the Revolutionary War, Marshall was appointed as a lieutenant in the Culpepper Minutemen, where he participated in the Battles of Great Bridge, Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, Stony Point, and Paulus Hook. It was fighting during the war, rather than his life as a lawyer and jurist, that had the most profound impact on Marshall, who said that the experience confirmed in him “the habit of considering America [rather than Virginia] as my country.”

During the winter of 1777–1778, Marshall was stationed at Valley Forge with General George Washington’s troops. It was there that he developed a close relationship with Washington, who appointed him chief legal officer. Washington had a profound influence on Marshall, who referred to him as “the greatest Man on earth.” Decades later, Marshall would write a multi-volume biography of Washington—the only book he ever wrote. After Washington died on December 14, 1799, it was Marshall, then a member of Congress, who eulogized him on the floor of the House of Representatives, delivering the famous words, actually written by Henry Lee, that Washington was “First in war. First in Peace. First in the hearts of his countrymen.” And it was Marshall who on December 30 introduced a resolution, which passed the same day, declaring a national day of mourning on February 22, Washington’s birthday.

In 1779, having attained the rank of captain, he returned to Virginia and enrolled at the College of William & Mary where he studied under George Wythe, a judge on the Virginia Court of Chancellery and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Marshall’s classmates included Bushrod Washington, a nephew of George Washington who would later serve with Marshall on the Supreme Court, and Spencer Roane, who later served with Marshall in the Virginia legislature and became a judge on the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. Roane was an ardent defender of state sovereignty and Jeffersonian Republicanism, and he and Marshall became bitter rivals, often clashing (sometimes under pseudonyms) over legal matters in public periodicals. In contrast to Roane’s states’ rights, strict-constructionist view, Marshall favored a strong executive and a robust national government capable of encouraging commerce; raising revenue (he had experienced firsthand Congress’s inability to raise money to pay and adequately supply the troops during the war); and defending American interests against threats from abroad.

After being admitted to the bar in 1780, Marshall initially returned to the army, but he resigned his commission a year later to begin practicing law. A cousin of Marshall’s, Edmund Randolph (of the Constitutional Convention’s Virginia—or Randolph—Plan fame), offered Marshall the opportunity to practice law out of his office in Richmond. Marshall accepted eagerly, and his practice and reputation grew rapidly, placing him in high demand.

Marshall was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1782 and reelected several times thereafter. In January 1783, he married Mary Willis “Polly” Ambler, daughter of the then-treasurer of Virginia. The marriage was a happy one, but Polly was devastated by the loss of four children through miscarriage or during infancy. Although six of their children lived to adulthood, Polly suffered from poor mental and physical health for most of her adult life, spending much of it living in seclusion. By contrast, Marshall was a tall and athletic man who walked several miles a day for most of his life, arising early and often returning before others had awakened. He was also a longtime member of Richmond’s exclusive Quoits Club, which limited its membership to 30. Quoits, which Marshall played every Saturday afternoon from May through September, was an old British game that was similar to modern-day horseshoes. As with most games played at exclusive clubs, eating, drinking, and convivial socializing were de rigueur.

In 1786, Marshall took on the representation of the heirs of Lord Thomas Fairfax in Hite v. Fairfax, an important dispute about land grants. Although Lord Fairfax’s heirs lost, the court of appeals acknowledged the legitimacy of the original grant of land from King James II. This was a significant victory for Marshall, who opposed post-Revolution efforts to invalidate colonial arrangements made before independence. A decade later, Marshall would argue his only case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Ware v. Hylton, which involved a dispute over the validity of debts owed to British creditors under the Treaty of Paris. Marshall lost the case, but the quality of his argument further cemented his status as an elite member of the bar.

Although not a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Marshall was elected in 1788 to serve as a delegate to the Virginia Ratifying Convention, where he played a prominent and ultimately successful role (by a narrow vote of 89 to 79) in urging his fellow delegates to ratify the new Constitution, further enhancing his reputation. During the Washington Administration, the President asked Marshall to serve in several prominent posts, including as minister to France. Marshall declined these invitations but remained one of Washington’s most ardent defenders both in the Virginia House of Delegates and in the court of public opinion. His support of Washington further irritated his cousin Thomas Jefferson, who had resigned from Washington’s Cabinet and was a frequent critic of the Administration’s policies. Marshall never forgave Jefferson for these criticisms.

In 1797, after the French refused to meet with American diplomats and began to attack American merchant ships, Marshall accepted an appointment by President John Adams to serve with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry as part of a three-member delegation to France. In what came to be known as the XYZ Affair, the French Foreign Minister, the Marquis de Talleyrand, set certain conditions for negotiation that included making a large loan to France and paying a substantial bribe to Talleyrand. The Americans refused. In time, Congress and the American public learned of the situation, which resulted in an embargo against France and an undeclared war known as the Quasi-War. Marshall’s handling of the situation made him extremely popular with the American public but not with Jefferson, a Francophile, who dismissed the XYZ Affair as a “dish cooked up by Marshall.”

In 1798, Marshall declined a Supreme Court appointment, recommending his friend Bushrod Washington, who later became one of Marshall’s staunchest allies on the Court. In 1799, at Washington’s urging, Marshall ran for and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Later that year, President Adams nominated him to replace Timothy Pickering as Secretary of State, in which capacity he negotiated the Convention of 1800 that ended the Quasi-War with France.

On January 20, 1801, shortly after losing the election to Thomas Jefferson, and with Republicans about to seize majority control of the Senate, Adams nominated Marshall to serve as the third Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Marshall was confirmed unanimously by the Senate one week later and assumed office on February 4, although he also continued to serve as Secretary of State until Adams’s term expired on March 4, an anomaly that was not uncommon at the time. Before offering the position to Marshall, Adams offered it to John Jay, who had served as the nation’s first Chief Justice. Jay spurned the offer because, in his view, the Court lacked “energy, weight, and dignity.” Nobody would say that after Marshall’s time on the Court ended 35 years later.

Jefferson, who was inaugurated a few short weeks after Marshall was confirmed as Chief Justice, remarked that the Federalists had “retreated into the judiciary as a stronghold.” Marshall did his utmost, at least in spirit, to keep it that way.

Life on the Bench

Perhaps no other appointment to the Supreme Court has been as consequential as Marshall’s. During his tenure, the Court was transformed from an afterthought to a powerful branch of government on a par with the legislative and executive branches. Marshall participated in over 1,000 cases, writing the majority opinion in roughly half of them and dissenting rarely. In several seminal cases, some of which are discussed below, he set forth in clear and compelling prose fundamental principles of law that remain in place today and did much to establish the modern federal judiciary.

Throughout his judicial career, Marshall confounded his critics and charmed his colleagues, who shared lodgings when the Court was hearing cases, often frustrating the Presidents who had appointed those colleagues in the hope that they would serve as a counterweight to Marshall. Marshall won them over with the force of his mind and lack of pretension, as well as his unfailing politeness, congeniality, and generosity when it came to sharing high-quality intoxicating beverages.

Marbury v. Madison (1803)

What is now acclaimed as Marshall’s greatest opinion—and the one that is certainly his most quoted—was the result of a political fight between Federalists and Republicans. After Jefferson and the Republicans swept the federal elections in 1800, President Adams and the Federalist-controlled Senate rushed to fill as many government positions as possible with Federalists. In addition to Marshall’s appointment to the Supreme Court, Adams nominated 42 justices of the peace, all of whom the Senate confirmed. After confirmation, the only remaining task was for then-Secretary of State Marshall to deliver the commissions to each nominee, but Marshall ran out of time. When Jefferson discovered that several commissions were still on Marshall’s desk, he refused to have his new Secretary of State, James Madison, deliver them.

One of the individuals whose commission had not been delivered, William Marbury, sued Madison in the Supreme Court. Marbury sought a writ of mandamus, an order from the Court directing Madison to deliver his commission. In a brilliant display of judicial and political legerdemain, on February 24, 1803, Marshall, writing for a unanimous Court, dismissed the case. The Court held that Marbury had a legal right to have the commission delivered and that Jefferson had acted lawlessly, but it also held that it could not provide relief because Marbury had filed his lawsuit in the wrong court.

Marbury relied on a federal statute that appeared to give the Court original jurisdiction to consider his lawsuit. While recognizing that Marbury had a legal right to his commission, Marshall declared with a flourish that “[t]he government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation, if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right.” The Constitution gave the Court original jurisdiction only over “cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party.” This case, Marshall observed, did not fit any of those categories.

That raised a difficult question: What should the Court do with a law that was passed by Congress but conflicts with the Constitution? Marshall declared that a law that is “repugnant to the Constitution is void.” Moreover, he said, “[t]he judicial power of the United States is extended to all cases arising under the Constitution.” While this was certainly a significant pronouncement, the piece de resistance was his declaration that “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Courts must decide on the operation of each.”

In one opinion, Marshall successfully sidestepped a potentially destructive conflict with the executive branch, affirmed the rule of law (and Jefferson’s violation of the law), and laid the foundations for the federal judiciary’s role in declaring what the law is in arbitrating constitutional disputes.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

Marbury was not the only political conflict that Marshall grappled with as Chief Justice. In 1819, the Court resolved an issue that had been debated for more than two decades: whether Congress could constitutionally establish a national bank.

During the Washington Administration, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton had proposed a flood of economic measures designed to bolster the new nation’s financial stability and credit at home and abroad. One of Hamilton’s proposals was that Congress should create a national bank. Jefferson, then Secretary of State, and Madison, then serving in Congress, opposed the idea. Madison in particular argued that Congress had no constitutional authority to create a bank, pushing back on Hamilton’s argument that a bank was “necessary and proper” for Congress to carry out its enumerated powers.

Hamilton prevailed when Congress passed legislation, which Washington signed into law, establishing the first Bank of the United States in 1791 and giving it a 20-year charter. When the charter expired in 1811, Congress declined to renew it, but after the federal government was forced to rely on high-interest private loans during the War of 1812, Congress renewed the Bank’s charter in 1816. However, the bank was poorly run, and this led several states to retaliate either by banning the Bank outright or by imposing taxes on the Bank’s local branches.

One such state was Maryland, which passed a law that required all out-of-state-banks to pay a yearly tax of $15,000 or a smaller stamp tax on every bank note issued. To test the constitutionality of Maryland’s tax on the bank, James McCulloch, the Bank’s Baltimore office manager, issued an unstamped note without paying the tax. Inevitably, McCulloch’s actions were challenged and found to violate the state law, paving the way for the case to reach the Supreme Court.

In 1819, Marshall issued the Court’s unanimous opinion in McCulloch v. Maryland,2 upholding the constitutionality of the Bank. His opinion bore an uncanny resemblance to arguments and words Hamilton had used to persuade Washington in 1791. The states, Marshall explained, no longer retained ultimate sovereignty to decide these kinds of issues because they had ratified the Constitution. The Constitution had been submitted to the people for their consideration, and “the people were at perfect liberty to accept or reject it, and their act was final. It required not the affirmance, and could not be negatived, by the State Governments. The Constitution, when thus adopted, was of complete obligation, and bound the State sovereignties.”

Congress, he next explained, had the power to establish a national bank. The Court rejected Maryland’s argument that the Necessary and Proper Clause gave Congress power to take an action only if it could not otherwise accomplish a permissible constitutional objective without taking that action. “Necessary,” Marshall explained, means “no more than” something that is “needful,” “requisite,” or “conducive to the complete accomplishment of the object.” Moreover, “[t]o employ the means necessary to an end is generally understood as employing any means calculated to produce the end, and not as being confined to those single means without which the end would be entirely unattainable.”

Marshall did not stop there. Lest his point be missed, he emphatically declared, “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are Constitutional.” In other words, if establishing a federal bank was conducive to Congress’s ability to execute one of its enumerated powers and was not expressly prohibited, it was constitutional. Maryland’s tax on the national bank, Marshall concluded, would undermine Congress’s exercise of its enumerated powers and was therefore impermissible.

This decision was both politically and constitutionally consequential. Not only did it resolve once and for all the issue of Congress’s authority to create a national bank and curtail states’ efforts to undermine federal legislation, but it also established that the Necessary and Proper Clause allows Congress more readily to fill in details that were understandably left out of the Constitution. As Marshall further explained, to detail all of the government’s powers “would partake of the prolixity of a legal code, and could scarcely be embraced by the human mind…. Its nature, therefore, requires that only its great outlines should be marked, its important objects designated, and the minor ingredients which compose those objects be deduced from the nature of the objects themselves.” He added memorably that “we must never forget that it is a Constitution we are expounding.”

John Marshall’s Legacy

Marshall wrote numerous opinions that continue to be studied and invoked to this day. In addition to Marbury and McCulloch, he authored Fletcher v. Peck3 and Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward,4 which laid the legal groundwork for American capitalism by limiting state legislatures’ ability to meddle with valid, preexisting private contracts; Gibbons v. Ogden,5 which has been called the “emancipation proclamation of American commerce”6 for protecting an uninhibited stream of interstate commerce that in turn created a vibrant national economy; and Cohens v. Virginia,7 which permitted anyone who believed that a state was violating his or her rights under the U.S. Constitution or federal law to seek a remedy in a federal court.

Marshall’s epochal tenure as Chief Justice, which spanned the presidencies of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Jackson, had a significant impact on the prestige of the Supreme Court. No one did more to enhance the authority and independence of the judiciary or had a greater impact on the law in this country than the “Great Chief Justice.”

It was Marshall who introduced the now-standard garb of black robes for Supreme Court justices as a sign of the republican nature of American government rather than the white or red robes more commonly worn by the British judicial elite. And it was Marshall who introduced the idea of majority opinions. Before his arrival, each justice would write and read his own opinion. After his arrival, more often than not, the Court would issue unanimous decisions with each justice free to write a separate concurrence or dissent. Unlike the prior practice, which left the impression that the law was incoherent, the new practice of majority opinions gave the Court’s opinions a sense of consistency, logic, and authority. The Court seemed to be speaking with one voice—and that voice was often Marshall’s.

John Adams later described his choice of Marshall to be Chief Justice as “the proudest act of my life.” Even Marshall’s rivals respected his intellect. John Randolph, who criticized Marshall’s opinion in Gibbons v. Ogden, described the Chief Justice this way: “No one admires more than I the extraordinary powers of Marshall’s mind; no one respects more his amiable deportment in private life. He is the most unpretending and unassuming of men. His abilities and virtues render him an ornament not only to Virginia, but to our Nation.”

In January 1833, Marshall’s longtime friend and colleague, Justice Joseph Story, published his highly influential, three-volume Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. In a touching tribute, he dedicated the work to Marshall:

Your expositions of constitutional law enjoy a rare and extraordinary authority. They constitute a monument of fame far beyond the ordinary memorials of political and military glory. They are destined to enlighten, instruct, and convince future generations; and can scarcely perish but with the memory of the constitution itself.… They remind us of some mighty river of our own country, which, gathering in its course the contributions of many tributary streams, pours at last its own current into the ocean, deep, clear, and irresistible.

On July 8, 1776, four days after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, bells rang throughout the city of Philadelphia to mark the occasion. It is believed that the Liberty Bell was one of them. On July 8, 1835, two days after Marshall died, bells rang out again in Philadelphia as his funeral cortege wended its way through the city. It is said (although the story may be apocryphal) that the Liberty Bell cracked that day, never to be rung again. And in tribute to its longtime distinguished member, the Quoits Club announced that it henceforth would have only 29 members.

Selected Primary Writings

Speech at the Virginia Ratifying Convention (June 20, 1788)8

Mr. Chairman, this part of the plan before us is a great improvement on that system from which we are now departing. Here are tribunals appointed for the decision of controversies which were before either not at all, or improperly, provided for. That many benefits will result from this to the members of the collective society, every one confesses….

…With respect to its cognizance in all cases arising under the Constitution and the laws of the United States, he [George Mason] says that, the laws of the United States being paramount to the laws of the particular states, there is no case but what this will extend to. Has the government of the United States power to make laws on every subject? Does he understand it so? Can they make laws affecting the mode of transferring property, or contracts, or claims, between citizens of the same state? Can they go beyond the delegated powers? If they were to make a law not warranted by any of the powers enumerated, it would be considered by the judges as an infringement of the Constitution which they are to guard. They would not consider such a law as coming under their jurisdiction. They would declare it void. It will annihilate the state courts, says the honorable gentleman. Does not every gentleman here know that the causes in our courts are more numerous than they can decide, according to their present construction? Look at the dockets. You will find them crowded with suits, which the life of man will not see determined. If some of these suits be carried to other courts, will it be wrong? They will still have business enough….

…Is it not necessary that the federal courts should have cognizance of cases arising under the Constitution, and the laws, of the United States? What is the service or purpose of a judiciary, but to execute the laws in a peaceable, orderly manner, without shedding blood, or creating a contest, or availing yourselves of force? If this be the case, where can its jurisdiction be more necessary than here?

To what quarter will you look for protection from an infringement on the Constitution, if you will not give the power to the judiciary? There is no other body that can afford such a protection….

Marbury v. Madison (1803)9

The very essence of civil liberty consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury. One of the first duties of government is to afford that protection….

The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation, if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right….

By the constitution of the United States, the President is invested with certain important political powers, in the exercise of which he is to use his own discretion, and is accountable only to his country in his political character and to his own conscience. To aid him in the performance of these duties, he is authorized to appoint certain officers, who act by his authority and in conformity with his orders.

In such cases, their acts are his acts; and whatever opinion may be entertained of the manner in which executive discretion may be used, still there exists, and can exist, no power to control that discretion. The subjects are political. They respect the nation, not individual rights, and being entrusted to the Executive, the decision of the Executive is conclusive….

But when the Legislature proceeds to impose on that officer other duties; when he is directed peremptorily to perform certain acts; when the rights of individuals are dependent on the performance of those acts; he is so far the officer of the law; is amenable to the laws for his conduct; and cannot at his discretion, sport away the vested rights of others.

The conclusion from this reasoning is, that where the heads of departments are the political or confidential agents of the Executive, merely to execute the will of the President, or rather to act in cases in which the Executive possesses a constitutional or legal discretion, nothing can be more perfectly clear than that their acts are only politically examinable. But where a specific duty is assigned by law, and individual rights depend upon the performance of that duty, it seems equally clear that the individual who considers himself injured, has a right to resort to the laws of his country for a remedy….

That the people have an original right to establish for their future government such principles as, in their opinion, shall most conduce to their own happiness is the basis on which the whole American fabric has been erected. The exercise of this original right is a very great exertion; nor can it nor ought it to be frequently repeated. The principles, therefore, so established are deemed fundamental. And as the authority from which they proceed, is supreme, and can seldom act, they are designed to be permanent….

It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Courts must decide on the operation of each.

So, if a law be in opposition to the Constitution, if both the law and the Constitution apply to a particular case, so that the Court must either decide that case conformably to the law, disregarding the Constitution, or conformably to the Constitution, disregarding the law, the Court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case. This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

If, then, the Courts are to regard the Constitution, and the Constitution is superior to any ordinary act of the Legislature, the Constitution, and not such ordinary act, must govern the case to which they both apply.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)10

…The government proceeds directly from the people; is “ordained and established” in the name of the people, and is declared to be ordained, “in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, and secure the blessings of liberty to themselves and to their posterity.”

The assent of the States in their sovereign capacity is implied in calling a convention, and thus submitting that instrument to the people. But the people were at perfect liberty to accept or reject it, and their act was final….

But the Constitution of the United States has not left the right of Congress to employ the necessary means for the execution of the powers conferred on the Government to general reasoning. To its enumeration of powers is added that of making “all laws which shall be necessary and proper, for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this constitution, in the government of the United States, or in any department thereof.”…

But the argument on which most reliance is placed, is drawn from the peculiar language of this clause. Congress is not empowered by it to make all laws, which may have relation to the powers conferred on the Government, but such only as may be “necessary and proper” for carrying them into execution. The word “necessary” is considered as controlling the whole sentence, and as limiting the right to pass laws for the execution of the granted powers, to such as are indispensable, and without which the power would be nugatory. That it excludes the choice of means, and leaves to Congress, in each case, that only which is most direct and simple.

Is it true that this is the sense in which the word “necessary” is always used? Does it always import an absolute physical necessity so strong that one thing to which another may be termed necessary cannot exist without that other? We think it does not. If reference be had to its use in the common affairs of the world or in approved authors, we find that it frequently imports no more than that one thing is convenient, or useful, or essential to another. To employ the means necessary to an end is generally understood as employing any means calculated to produce the end, and not as being confined to those single means without which the end would be entirely unattainable. Such is the character of human language that no word conveys to the mind in all situations one single definite idea, and nothing is more common than to use words in a figurative sense. Almost all compositions contain words which, taken in their rigorous sense, would convey a meaning different from that which is obviously intended. It is essential to just construction that many words which import something excessive should be understood in a more mitigated sense—in that sense which common usage justifies. The word “necessary” is of this description. It has not a fixed character peculiar to itself. It admits of all degrees of comparison; and is often connected with other words which increase or diminish the impression the mind receives of the urgency it imports. A thing may be necessary, very necessary, absolutely or indispensably necessary. To no mind would the same idea be conveyed, by these several phrases….

…The subject is the execution of those great powers on which the welfare of a Nation essentially depends. It must have been the intention of those who gave these powers to insure, as far as human prudence could insure, their beneficial execution. This could not be done by confiding the choice of means to such narrow limits as not to leave it in the power of Congress to adopt any which might be appropriate, and which were conducive to the end. This provision is made in a Constitution intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs. To have prescribed the means by which Government should, in all future time, execute its powers would have been to change entirely the character of the instrument and give it the properties of a legal code. It would have been an unwise attempt to provide by immutable rules for exigencies which, if foreseen at all, must have been seen dimly, and which can be best provided for as they occur. To have declared that the best means shall not be used, but those alone without which the power given would be nugatory, would have been to deprive the legislature of the capacity to avail itself of experience, to exercise its reason, and to accommodate its legislation to circumstances….

We admit, as all must admit, that the powers of the Government are limited, and that its limits are not to be transcended. But we think the sound construction of the Constitution must allow to the national legislature that discretion with respect to the means by which the powers it confers are to be carried into execution which will enable that body to perform the high duties assigned to it in the manner most beneficial to the people. Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are Constitutional.

Cohens v. Virginia (1821)11

The American States, as well as the American people, have believed a close and firm Union to be essential to their liberty and to their happiness. They have been taught by experience that this Union cannot exist without a government for the whole, and they have been taught by the same experience that this government would be a mere shadow, that must disappoint all their hopes, unless invested with large portions of that sovereignty which belongs to independent States….

…But a Constitution is framed for ages to come, and is designed to approach immortality as nearly as human institutions can approach it. Its course cannot always be tranquil. It is exposed to storms and tempests, and its framers must be unwise statesmen indeed if they have not provided it, as far as its nature will permit, with the means of self-preservation from the perils it may be destined to encounter….

…The people made the constitution, and the people can unmake it. It is the creature of their will, and lives only by their will. But this supreme and irresistible power to make or to unmake, resides only in the whole body of the people; not in any sub-division of them….

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)12

It is the power to regulate, that is, to prescribe the rule by which commerce is to be governed. This power, like all others vested in Congress, is complete in itself, may be exercised to its utmost extent, and acknowledges no limitations, other than are prescribed in the constitution. These are expressed in plain terms, and do not affect the questions which arise in this case, or which have been discussed at the bar. If, as has always been understood, the sovereignty of Congress, though limited to specified objects, is plenary as to those objects, the power over commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, is vested in Congress as absolutely as it would be in a single government, having in its Constitution the same restrictions on the exercise of the power as are found in the Constitution of the United States. The wisdom and the discretion of Congress, their identity with the people, and the influence which their constituents possess at elections, are, in this, as in many other instances, as that, for example, of declaring war, the sole restraints on which they have relied, to secure them from its abuse. They are the restraints on which the people must often rely solely, in all representative governments.

Osborn v. Bank of the United States (1824)13

…Judicial power, as contradistinguished from the power of the laws, has no existence. Courts are the mere instruments of the law, and can will nothing. When they are said to exercise a discretion, it is a mere legal discretion, a discretion to be exercised in discerning the course prescribed by law; and, when that is discerned, it is the duty of the Court to follow it. Judicial power is never exercised for the purpose of giving effect to the will of the Judge; always for the purpose of giving effect to the will of the Legislature; or, in other words, to the will of the law.

Recommended Readings

- Letters of John Marshall in Dartmouth College Libraries. See “Marshall, John, 1755–1835,” Dartmouth Libraries Archives & Manuscripts, https://archives-manuscripts.dartmouth.edu/agents/people/7007 (accessed March 28, 2025).

- Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer of a Nation (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1996).

- Richard Brookhiser, John Marshall: The Man Who Made the Supreme Court (New York: Basic Books, 2018).

- Charles F. Hobson, ed., The Papers of John Marshall, Digital Edition, University of Virginia Press, https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/JNML.html (accessed March 28, 2025).

- Dudley Warner Woodbridge, “John Marshall in Perspective,” Pennsylvania Bar Association Quarterly, Vol. 27 (1956), pp. 192–204, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1360&context=popular_media (accessed March 28, 2025).

Notes

[1] William H. Rehnquist, “John Marshall: Remarks of October 6, 2000,” William & Mary Law Review, Vol. 43, No. 4 (2001–2002), pp. 1555–1556, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol43/iss4/9/ (accessed March 28, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[2] 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819).

[3] 10 U.S. 87 (1810).

[4] 17 U.S. 518 (1819).

[5] 22 U.S. 1 (1824).

[6] Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer of a Nation (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1996), p. 473, quoting Charles Warren, History of the American Bar (Boston: Little, Brown, 1911), p. 396.

[7] 19 U.S. 264 (1821).

[8] Jonathan Elliot, ed., The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, 2nd ed. (Washington: Printed for the Editor, 1836), Vol. III, pp. 551–554, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1907/1314.03_Bk.pdf (accessed April 10, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[9] 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803).

[10] 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819).

[11] 19 U.S. 264 (1821).

[12] 22 U.S. 1 (1824).

[13] 22 U.S. 738 (1824).