—Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Paine, June 19, 17921

Life

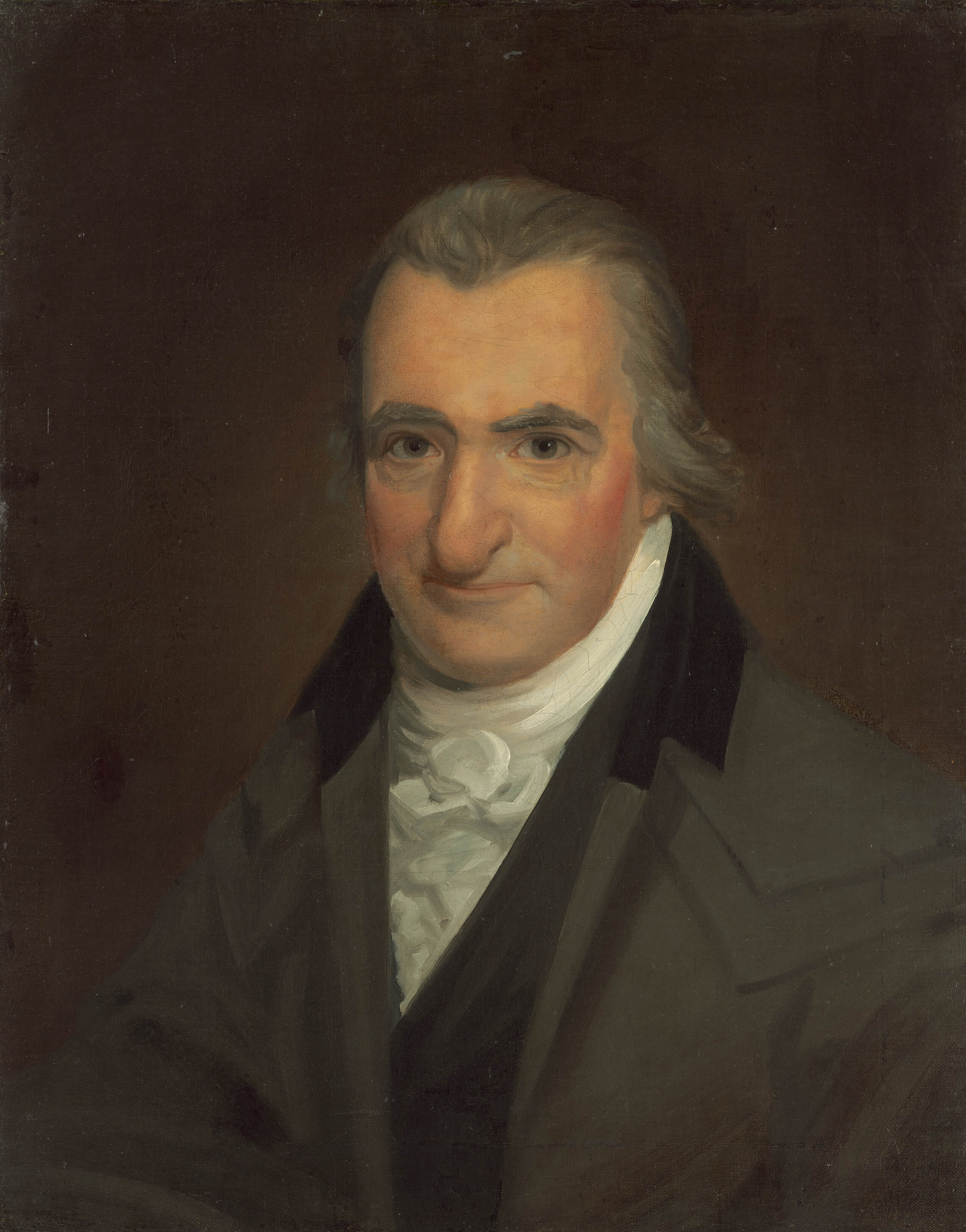

Thomas Paine was born January 29, 1737, in Thetford, county of Norfolk, England. He was the son of Joseph Pain and Frances Cocke Pain (spelling changed to “Paine” by Thomas). After spending some of his teenage years at sea, Paine went to work as a corset-maker and then as a tax collector. He married twice: in 1757 to Mary Lambert, who died in childbirth, and in 1771 to Elizabeth Ollive, from whom he separated in 1774, the year he emigrated to America. He had no children. Paine died on June 8, 1809, in New York City.

Education

Paine attended village primary school from ages six to 13 and thereafter was self-taught with interests in public affairs and science.

Religion

Quaker (by upbringing), Deist

Political Affiliation

British Whig, American Patriot, French Girondin

Highlights and Accomplishments

1775: Author, Common Sense

1775–1776: Editor, Pennsylvania Magazine

1776–1783: Author, The American Crisis

1776–1783: Aide-de-camp to General Nathanael Greene

1777–1779: Secretary to the Committee of Foreign Affairs of the Continental Congress

1780: Clerk of the Pennsylvania Assembly

1781: Fundraising mission to France

1787: Travel to England to promote design of iron bridge

1791, 1792: Author, Rights of Man

1792: Indictment for seditious libel in England; flight to France; tried and convicted in absentia

1792–1793, 1795: Member of French National Convention

1793–1794: Arrest and imprisonment in France

1794, 1795, 1807: Author, Age of Reason

1795: Author, “Dissertation on First Principles of Government”

1795–1796: Author, Agrarian Justice

1802: Return to America

Paine in America (1774–1787)

Thomas Paine began writing his pamphlet Common Sense about a year after coming to America as a penniless immigrant. The colonies had spent the preceding 10 years remonstrating with the British government about taxes and assorted other grievances. Their complaining came to a head in 1774 following Parliament’s passage of the Coercive Acts2 in response to the Boston Tea Party.3 But few of the delegates to the Continental Congress4 assembled in Philadelphia yet thought in terms of independence. A return to the status quo was still the dominant position as declared by Congress (Declaration and Resolves, 1774) and as urged by such prominent individuals as Thomas Jefferson (Summary View of the Rights of British America, 1774) and James Wilson (Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament, 1774). In the fall of 1775, John Dickinson persuaded the Pennsylvania Assembly to instruct its delegates to Congress to vote against independence if anyone dared to propose it. Eventually, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia did propose it on July 2, 1776. Paine’s pamphlet appeared in January 1776. Widely read, reprinted, and distributed, it turned public opinion in favor of independence.

Common Sense consists of four parts: an explanation of the origin and purpose of government; an attack on monarchy and the principle of hereditary succession; a defense of separation and independence from Britain against supporters of reconciliation; and an assurance that America could prevail in the coming war (in addition to sundry miscellaneous items).

Government is distinct from society, Paine averred, for society (a blessing) satisfies our wants while government (a necessary evil) polices our wickedness. The first government was an assembly of similarly situated people (gathered under the branches of a tree) issuing regulations enforced by public opinion. As numbers multiplied and distances increased, representatives replaced the people assembled, and frequent elections kept those representatives true to their trusts while preventing the emergence of a permanent ruling class. Simplicity was the hallmark of this government; freedom and security were its purposes.

To Paine, the much-heralded mixed government of Great Britain,5 with power divided among the king, noblemen, and commoners, was a gross departure from the true nature of government. Its complexity cloaked responsibility and invited abuse. Only the Commons—the popular, or republican, part—contributed to freedom; the monarchical and aristocratic parts were remnants of ancient tyrannies. The supposed balance among the three parts—thought to be liberty-preserving and the reason why Britain’s system of government surpassed all others—was unsustainable because power gravitated to the monarchical part, which was able to subordinate the other parts by dispensing positions and pensions. With the ascendancy of the monarch, security was lost because kings had little else to do besides make war.

The elevation of one man and family above the general population was, to Paine, an affront to human equality, and the perpetuation of their descendants in power through hereditary succession was a dangerous absurdity. The offspring did not inherit the qualities of the parent, and some successors were but children at the point of succession. If the stated reason for monarchy was stability or that hereditary succession prevented civil wars, the English example provided conclusive evidence to the contrary: Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, England had suffered, by Paine’s count, eight civil wars and 19 rebellions. Moreover, the first of these kings, William the Conqueror, was but a bastard-born French bandit who installed himself as king by force.

American colonists, having lived under British rule for a century and a half, could be excused for thinking that survival in a dangerous world depended on maintaining their allegiance to the Crown. But America was threatened, Paine thought, not by impending separation from Britain, but rather by continued connection to a country whose enemies were America’s enemies only because of that association. Moreover, those who cited ties of affection to the mother country should realize that not Britain alone, but all of Europe, was America’s true parent, as immigrants had come from all corners of the continent. The great distance separating Britain from America and the difficulty of administering from afar further made the case for independence, in addition to which the British king had no interest in seeing America flourish, for a flourishing America would become a larger, richer, and more powerful competitor state, exposing the folly of an island attempting to rule a continent.

Britain, Paine argued, was not as indomitable as she might have seemed. Even though her navy was by far the world’s largest, it patrolled the globe, and only a fraction of the fleet was available for service in America. A colonial navy one-20th the size of Britain’s should be enough to neutralize Britain’s advantage. The materials for building it were plentiful, the sailors to man it were in sufficient supply, and the debt incurred would help to bind the colonies together. Assistance from France and Spain would be denied if America saw herself as a British colony, currently disgruntled but wanting to be welcomed back into the empire. On the other hand, a declaration of independence would announce to the world that America was a separate country ready for partnership and trade.

Paine in England (1787–1792)

After the Treaty of Paris, which concluded the Revolutionary War in 1783, Paine shifted his attention from public affairs to scientific pursuits. In addition to his many other inventions (for example, a smokeless candle), he designed a single-span iron bridge meant to cross the Schuylkill River at Philadelphia. When he could not secure the financial backing that construction required, he sailed to Europe in April 1787, a month before the delegates to the Constitutional Convention assembled in Philadelphia, hoping to market his design. Back and forth across the Channel he went, consulting with engineers, manufacturers, and persons of influence. He spent the early months of the French Revolution (November 1789–March 1790) in France and the spring and summer of 1790 in London constructing a dry-land demonstration bridge (this one for the Thames River) that remained on public display for a year.

Then, in November 1790, Edmund Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Paine knew Burke, corresponded with him, and judged him to be a true friend of republican revolution much like himself, for Burke had vigorously supported the American cause as a member of Parliament. But Burke’s Reflections was a total denunciation of the French Revolution. Paine thought differently about events in France and hurriedly wrote a rebuttal in a book titled Rights of Man, the first part of which appeared in March 1791.

The point of departure for both authors was England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688, which deposed one monarch, James II, and installed another—two, in fact—James’s nephew, William of Orange, and James’s daughter, Mary, who was William’s wife. The Declaration of Right, drafted for the occasion, tried to explain how the line of succession could thus be adjusted.

In 1789, an association called the Revolution Society, which met annually in London to commemorate the Revolution of 1688, hosted Richard Price, a dissenting minister and pamphleteer. In an imagined address to the king, Price praised him “as almost the only lawful King in the world, because the only one who owes his crown to the choice of the people.”6 Price then listed among the principles of the Revolution the people’s right “to choose [their] own governors, to cashier them for misconduct, and to frame a government for [them]selves.”7 He concluded by describing the French Revolution as an extension of the English Revolution.

Price’s address, “A Discourse on the Love of Our Country,” was what spurred Burke to action. Responding in his Reflections, Burke countered that the Declaration of Right, far from establishing the right of the people to choose their governors, cashier their governors, and frame government anew, did all it could to hide the implication of such rights—which, if they ever existed, were then and forever renounced—and to reaffirm the principle of hereditary succession.8 The current king, insisted Burke, held title to the throne as an inheritance from his ancestors and “in contempt of the choice of the Revolution Society.”9

In Rights of Man, Paine admitted—as he had to—that monarchs after James II were hereditary heirs and not the product of popular choice.10 That being the case, in what sense could it be said that the Revolution of 1688 had conferred and ever since enshrined the people’s three rights of self-rule: to choose, to cashier, and to frame for themselves?

Paine began by distinguishing a delegated right from an assumed right. Parliament, said Paine, exercised a delegated right (delegated by those who elected its members) when it deposed James II, but it exercised an assumed right when it prohibited future Parliaments from doing the same. Assumed rights are an abuse—an abuse for which James II was cashiered.

Paine’s guiding principle was that all generations are free and equal, discrete and disconnected; they are not bound by their ancestors, nor can they presume to bind their descendants. Laws that continue in force through successive generations do so with the consent (even if it is only tacit) of the living, not because past laws cannot be repealed. They can be repealed, and a corollary to the above principle explains why: “As government is for the living, and not for the dead, it is the living only that has any right in it.”11

Paine traced the source of rights to man’s creation by God. All religions, Paine affirmed, testify to the unity and equality of man as a species, each of whose members, of whatever time or place, is endowed with the same rights. These rights are called natural rights. They include the rights of the mind and the right to act in pursuit of comfort and happiness.

The second category of rights is civil rights. Civil rights belong to man by virtue of his membership in society, just as natural rights belong to man by virtue of his existence. Civil rights derive from natural rights, specifically those natural rights that cannot be enjoyed in society because individuals lack the power to exercise them. Personal security and judgment are examples. The right to be a judge of one’s own cause—a right of the mind—continues, but the right to seek redress is surrendered because without the power of enforcement the right is ineffectual. Three conclusions follow: (1) a civil right is a natural right surrendered; (2) civil power is the aggregate of these surrendered rights, whose purposes (such as security) are achievable only by the collective; and (3) civil power cannot be used to invade those natural rights retained (such as freedom of conscience).

In line with the social-contract theory of the day,12 Paine held that society is formed by a compact among the people, while legitimate government is formed by a constitution made by the people. No compact exists between the people and the government because government is the creation of the people, its deputy, and not an equal partner. The work of a constitution is to organize the offices of government, to confer on each its powers, to devise restraining mechanisms, and to state the principles by which government should act and be bound. A constitution, furthermore, should be written (following the American example) to serve as a guide and check on government lawmaking. Government makes law in compliance with the constitution, which is made by the people or their representatives.

Accordingly, Paine believed that England’s government since the time of William the Conqueror had been illegitimate. It was founded on force, and its rights, rather than delegated, were assumed. England, in fact, had no constitution worthy of the name. What passed for a constitution—and was called such by Burke—was the slow, piecemeal reclaiming of assumed rights over a period of centuries, beginning with Magna Carta.13 England, argued Paine, should have “expelled the usurpation” in its entirety,14 as did the French, whose constitution was superior to the English constitution, so-called, across a wide range of indices, including representation, terms of office, war and peace, and religious tolerance.

Paine waited almost a year before bringing out Part II of Rights of Man. He explained in the preface that he wished to test the public reception accorded to Part I and that he was waiting for a promised reply from Burke. Robust sales testified to the popularity of Paine’s ideas, and the promised reply never came; Burke wrote another book instead.

Though Paine returned to many of the topics covered in Part I and in Common Sense, his remarks sounded more radical the second or third time around. For example, society is natural, practically self-regulating, and capable of existing without government, while government is an imposition (not even a necessary evil), often undermining order instead of providing it. All previous governments (not just Britain’s) had their founding in banditry, after which the bandit became the monarch, plunder became revenue, and usurpation became inheritance. Hereditary monarchy is not only insulting to human equality (treating the population, like the land, as inherited property), but also incompetent, or at best accidentally competent, because good governance depends on the uncertain character of the ruler, who is wholly the ruler whether immature, idiotic, or foreign-born. How can one individual, sequestered in a palace, come by the practical knowledge needed to rule society in all its manifold parts?

Government that accords with nature satisfies two requirements: It is devoted to the common good and has the requisite knowledge to achieve the common good. A republic (res publica, Latin for “public benefit”) satisfies the first requirement, and a representative democracy satisfies the second (in fact, a representative democracy is sometimes called a republic). The ancients were unfamiliar with representation, and when their democratic polities grew in population and territory, the resulting unruliness allowed monarchs to come to power. But representative democracy can expand indefinitely and still cohere, obviating the need for monarchy to restore order. Moreover, talent is best discovered and best utilized by representative democracy, which is like the hub of a wheel with elected representatives as spokes, bringing vital information to the center. Monarchy lives under the conceit that talent is transmitted by hereditary descent.

Up to this point, Paine had written from the vantage of a libertarian, favoring small government, low taxes, maximum liberty, and a self-regulating society naturally disposed to peace and harmony. That changed in the last chapter of Part II, “Ways and Means of Improving the Condition of Europe….” Here Paine sounded the part of a social democrat, espousing free-spending and big government responsible for the welfare of the poor.

What triggered this turnabout was a close study of the British government’s budget for the year ending September 1788 and the revenues raised to support it. Paine calculated that interest on the national debt accounted for £9,000,000 of the £17,000,000 collected in taxes and annual expenses accounted for £8,000,000. Looking back to the budgets of less extravagant and more peaceful times, Paine figured that with the elimination of waste and the creation of alliances, the government could reduce its cost to £1,500,000. When subtracted from the £8,000,000 in annual expenses (the £9,000,000 debt had to be serviced), a surplus of £6,500,000 would remain for poor relief, education, child support, old-age and veteran benefits, and stipends for specific groups adversely affected by the change. Taxes on the poor would end, and a progressive tax on the rich would be instituted. Other proposals with a modern ring included opinion polls, election reform, and taxes on capital gains.

In a later pamphlet, Agrarian Justice (1795–1796), Paine continued in this vein, proposing an inheritance tax of 10 percent on landed and personal property, from which revenue a stipend of £15 would be paid to the young upon reaching maturity (age 21) and £10 annually would be paid to the elderly (age 50) until their deaths (effectively the same as the U.S. Social Security system).15

Paine in France (1792–1802)

Paine published Rights of Man, Part II, in February 1792. In May, the British government indicted him for seditious libel; in September, he fled to France; and in December, he was convicted in absentia.

In France, Paine was elected to the French National Convention representing Pas-de-Calais, despite his status as a foreigner and inability to speak the language. The Convention’s charge was to write a fully republican constitution without a monarch as executive. A year later, during the ascendancy of the Jacobin faction, Maximilien Robespierre, its leader, ordered the arrest and imprisonment of Paine, who had aligned himself with the comparatively moderate Girondin faction. It was late December 1793 at the height of the Reign of Terror.16

For seven months, Paine was confined in the Luxembourg Prison awaiting likely execution. His time came in July 1794, when a jailer marked his cell door with chalk, signifying that Paine was among those slated for beheading in the morning, but a remarkable twist of fate intervened to save his life: The cell door that day was open to the corridor, and the inattentive jailer marked the inside of the door. When morning came, the jailer on duty, seeing no mark on the outside of the door, passed by Paine’s cell. A few days later, on July 27, Robespierre fell from power, and Paine was spared his date with the guillotine, though he remained in prison for another three months until early November. The following year, he reclaimed his seat in the Convention.

Paine spent his over 10 months of incarceration writing Age of Reason, Part I (Part II followed in 1795). The book mounted an uncompromising, closely argued critique of revealed religion, especially Christianity. In a biographical statement tucked inside, Paine admitted that from an early age, Christianity had repelled him because he found it intellectually unsatisfying and morally distasteful.

A few of Paine’s objections are worth noting here: (1) Revelation is not revelation except to the immediate recipient; for everyone else, it is hearsay—and what is a Church built on hearsay? (2) Biblical stories have suspiciously pagan antecedents, such as Jesus Christ, Son of God, born of a woman and the woman-born progeny sired by Jupiter, or Satan cast into hell and the rebellious race of Giants buried under a mountain—might comfortable familiarity with pagan antecedents be the origin of these and other biblical stories? (3) Church Fathers (or as Paine preferred, “Mythologists”) authenticated the books of the Bible by the all-too-human method of voting—but what would count as the Word of God if the vote had come out differently?

For Paine, the Word of God is creation, not the Bible hampered as it is by all the limitations of language. Creation is known directly by human reason pondering the ways of nature. The products of reason’s investigations are the sciences and their practical applications. The sum of the sciences—together called “natural philosophy” with astronomy at the center—is true theology, and scientific inquiry is true worship, revealing the power, wisdom, munificence, and mercy of God.

It was of utmost importance to Paine that God created multiple worlds rather than just one: “[A]ll our knowledge of science is derived from the revolutions…which those several planets or worlds of which our system is composed make in their circuit round the Sun.”17 The ancients recognized a multiplicity of worlds, but their astronomical discoveries were for centuries suppressed by Christianity, whose story of creation (in six days), the fall (Adam and Eve expelled from the garden), and redemption (Christ as savior) implies but a single world (“Are we to suppose that every world in the boundless creation had an Eve, an apple, a serpent, and a redeemer?”).18 The ancients invented science; Christianity persecuted science, the trial of Galileo being a prime example.

Paine’s own faith was that of a Deist.19 He believed in a single creator God known by reason; he believed that religious duty consists of fair and kindly treatment of fellow human beings, all of whom are equal; and he hoped for happiness in an afterlife that imitation of God’s goodness might bring him.

Paine Back in America (1802–1809)

Paine returned to a frosty reception in America. His attack on Christianity, while congenial enough to the antireligious French, earned him the contempt of most Americans. Just as destructive was his intemperate letter to President George Washington, written in 1795 and published in 1796, when no reply was received. Paine accused Washington of having cooperated in his imprisonment and of having done nothing to help secure his release. Paine further impugned Washington’s military accomplishments and attacked Washington’s Administration, charging it with pusillanimity toward the British and ingratitude toward the French. Only after Thomas Jefferson became President (1801), and upon invitation from Jefferson, did Paine return to America.

Paine lived out his remaining days on his farm in New Rochelle, New York. The farm was a long-ago gift from the Continental Congress. There he resumed his literary labors, conveying his thoughts on current affairs in letters addressed “To the Citizens of the United States” (1802–1803 and 1805); submitting a memorandum to the U.S. Congress on his designs for an iron bridge (1803); gracing Pennsylvanians, busy drafting their third state constitution, with his latest reflections on constitutional reform (1805); and publishing the third part of Age of Reason (1807).

Paine died on June 8, 1809, in New York City. His death went largely unnoticed, and only six people attended the funeral. His remains were buried on his farm because the local Quakers would not allow burial in their graveyard as Paine had requested in his will. In 1819, William Cobbett, a like-minded English radical, exhumed the body and transported it to England for reburial on a site worthy of a great man. Nothing came of these plans, and after a time, the bones of Thomas Paine vanished.

Selected Primary Writings

“Dissertation on First Principles of Government” (1795)20

The true and only true basis of representative government is equality of Rights. Every man has a right to one vote, and no more in the choice of representatives. The rich have no more right to exclude the poor from the right of voting, or of electing and being elected, than the poor have to exclude the rich; and whenever it is attempted, or proposed, on either side, it is a question of force and not of right. Who is he that would exclude another? That other has a right to exclude him.

That which is now called aristocracy implies an inequality of right; but who are the persons that have a right to establish this inequality? Will the rich exclude themselves? No. Will the poor exclude themselves? No. By what right then can any be excluded? It would be a question, if any man or class of men have a right to exclude themselves; but, be this as it may, they cannot have the right to exclude another. The poor will not delegate such a right to the rich, nor the rich to the poor, and to assume it is not only to assume arbitrary power, but to assume a right to commit robbery. Personal rights, of which the right of voting for representatives is one, are a species of property of the most sacred kind: and he that would employ his pecuniary property, or presume upon the influence it gives him, to dispossess or rob another of his property or rights, uses that pecuniary property as he would use fire-arms, and merits to have it taken from him.

Inequality of rights is created by a combination in one part of the community to exclude another part from its rights. Whenever it be made an article of a constitution, or a law, that the right of voting, or of electing and being elected, shall appertain exclusively to persons possessing a certain quantity of property, be it little or much, it is a combination of the persons possessing that quantity to exclude those who do not possess the same quantity. It is investing themselves with powers as a self-created part of society, to the exclusion of the rest.

It is always to be taken for granted, that those who oppose an equality of rights never mean the exclusion should take place on themselves; and in this view of the case, pardoning the vanity of the thing, aristocracy is a subject of laughter. This self-soothing vanity is encouraged by another idea not less selfish, which is that the opposers conceive they are playing a safe game, in which there is a chance to gain and none to lose; that at any rate the doctrine of equality includes them, and that if they cannot get more rights than those whom they oppose and would exclude they shall not have less. This opinion has already been fatal to thousands, who, not contented with equal rights, have sought more till they lost all, and experienced in themselves the degrading inequality they endeavoured to fix upon others.

In any view of the case it is dangerous and impolitic, sometimes ridiculous, and always unjust to make property the criterion of the right of voting. If the sum or value of the property upon which the right is to take place be considerable it will exclude a majority of the people and unite them in a common interest against the government and against those who support it; and as the power is always with the majority, they can overturn such a government and its supporters whenever they please.

If, in order to avoid this danger, a small quantity of property be fixed, as the criterion of the right, it exhibits liberty in disgrace, by putting it in competition with accident and insignificance. When a broodmare shall fortunately produce a foal or a mule that, by being worth the sum in question, shall convey to its owner the right of voting, or by its death take it from him, in whom does the origin of such a right exist? Is it in the man, or in the mule? When we consider how many ways property may be acquired without merit, and lost without crime, we ought to spurn the idea of making it a criterion of rights.

But the offensive part of the case is that this exclusion from the right of voting implies a stigma on the moral character of the persons excluded; and this is what no part of the community has a right to pronounce upon another part. No external circumstance can justify it: wealth is no proof of moral character; nor poverty of the want of it. On the contrary, wealth is often the presumptive evidence of dishonesty; and poverty the negative evidence of innocence. If therefore property, whether little or much, be made a criterion, the means by which that property has been acquired ought to be made a criterion also.

The only ground upon which exclusion from the right of voting is consistent with justice would be to inflict it as a punishment for a certain time upon those who should propose to take away that right from others. The right of voting for representatives is the primary right by which other rights are protected. To take away this right is to reduce a man to slavery, for slavery consists in being subject to the will of another, and he that has not a vote in the election of representatives is in this case. The proposal to disenfranchise any class of men is as criminal as the proposal to take away property. When we speak of right we ought always to unite with it the idea of duties: rights become duties by reciprocity. The right which I enjoy becomes my duty to guarantee it to another, and he to me; and those who violate the duty justly incur a forfeiture of the right.

In a political view of the case, the strength and permanent security of government is in proportion to the number of people interested in supporting it. The true policy therefore is to interest the whole by an equality of rights, for the danger arises from exclusions. It is possible to exclude men from the right of voting, but it is impossible to exclude them from the right of rebelling against the exclusion; and when all other rights are taken away the right of rebellion is made perfect.

While men could be persuaded they had no rights, or that rights appertained only to a certain class of men, or that government was a thing existing in right of itself, it was not difficult to govern them authoritatively. The ignorance in which they were held, and the superstition in which they were instructed, furnished the means of doing it. But when the ignorance is gone, and the superstition with it; when they perceive the imposition that has been acted upon them; when they reflect that the cultivator and the manufacturer are the primary means of all the wealth that exists in the world, beyond what nature spontaneously produces; when they begin to feel their consequences by their usefulness, and their right as members of society, it is then no longer possible to govern them as before. The fraud once detected cannot be re-enacted. To attempt it is to provoke derision, or invite destruction.

That property will ever be unequal is certain. Industry, superiority of talents, dexterity of management, extreme frugality, fortunate opportunities, or the opposite, or the means of those things, will ever produce that effect, without having recourse to the harsh, ill-sounding names of avarice and oppression; and besides this there are some men who, though they do not despise wealth, will not stoop to the drudgery or the means of acquiring it, nor will be troubled with it beyond their wants or their independence; while in others there is an avidity to obtain it by every means not punishable; it makes the sole business of their lives, and they follow it as a religion. All that is required with respect to property is to obtain it honestly, and not employ it criminally; but it is always criminally employed when it is made a criterion for exclusive rights.

In institutions that are purely pecuniary, such as that of a bank or a commercial company, the rights of members composing that company are wholly created by the property they invest therein; and no other rights are represented in the government of that company than what arise out of that property; neither has that government cognizance of anything but property.

But the case is totally different with respect to the institution of civil government, organized on the system of representation. Such a government has cognizance of everything, and of every man as a member of the national society, whether he has property or not; and, therefore, the principle requires that every man, and every kind of right, be represented, of which the right to acquire and to hold property is but one, and that not of the most essential kind. The protection of a man’s person is more sacred than the protection of property; and besides this, the faculty of performing any kind of work or services by which he acquires a livelihood, or maintaining his family, is of the nature of property. It is property to him; he has acquired it; and it is as much the object of his protection as exterior property, possessed without that faculty, can be the object of protection in another person.

I have always believed that the best security for property, be it much or little, is to remove from every part of the community, as far as can possibly be done, every cause of complaint, and every motive to violence, and this can only be done by an equality of rights. When rights are secure, property is secure in consequence. But when property is made a pretence for unequal or exclusive rights, it weakens the right to hold the property, and provokes indignation and tumult; for it is unnatural to believe that property can be secure under the guarantee of a society injured in its rights by the influence of that property….

An enquiry into the origin of Rights will demonstrate to us that rights are not gifts from one man to another, nor from one class of men to another; for who is he who could be the first giver, or by what principle, or on what authority, could he possess the right of giving? A declaration of rights is not a creation of them, nor a donation of them. It is a manifest of the principle by which they exist, followed by a detail of what the rights are; for every civil right has a natural right for its foundation, and it includes the principle of a reciprocal guarantee of those rights from man to man. As, therefore, it is impossible to discover any origin of rights otherwise than in the origin of man, it consequently follows, that rights appertain to man in right of his existence only, and must therefore, be equal to every man. The principle of an equality of rights is clear and simple. Every man can understand it, and it is by understanding his rights that he learns his duties; for where the rights of men are equal, every man must finally see the necessity of protecting the rights of others as the most effectual security for his own….

In a state of nature all men are equal in rights, but they are not equal in power; the weak cannot protect themselves against the strong. This being the case, the institution of civil society is for the purpose of making an equalization of powers that shall be parallel to, and a guarantee of, the equality of rights. The laws of a country, when properly constructed, apply to this purpose. Every man takes the arm of the law for his protection as more effectual than his own; and therefore every man has an equal right in the formation of the government, and of the laws by which he is to be governed and judged. In extensive countries and societies, such as America and France, this right in the individual can only be exercised by delegation, that is, by election and representation; and hence it is that the institution of representative government arises.

Hitherto, I have confined myself to matters of principle only. First, that hereditary government has not a right to exist; that it cannot be established on any principle of right; and that it is a violation of all principle. Secondly, that government by election and representation has its origin in the natural and eternal rights of man; for whether a man be his own lawgiver, as he would be in a state of nature; or whether he exercises his portion of legislative sovereignty by his own person, as might be the case in small democracies where all could assemble for the formation of the laws by which they were to be governed; or whether he exercises it in the choice of persons to represent him in a national assembly of representatives, the origin of the right is the same in all cases. The first, as is before observed, is defective in power; the second, is practicable only in democracies of small extent; the third, is the greatest scale upon which human government can be instituted.

Next to matters of principle are matters of opinion, and it is necessary to distinguish between the two. Whether the rights of men shall be equal is not a matter of opinion but of right, and consequently of principle; for men do not hold their rights as grants from each other, but each one in right of himself. Society is the guardian but not the giver. And as in extensive societies, such as America and France, the right of the individual in matters of government cannot be exercised but by election and representation, it consequently follows that the only system of government consistent with principle, where simple democracy is impracticable, is the representative system….

Rights of Man, Part II (1792)21

I will conclude this work with stating in what light religion appears to me.

If we suppose a large family of children, who, on any particular day, or particular circumstance, made it a custom to present to their parent some token of their affection and gratitude, each of them would make a different offering, and most probably in a different manner. Some would pay their congratulations in themes of verse or prose, by some little devices, as their genius dictated, or according to what they thought would please; and, perhaps, the least of all, not able to do any of those things, would ramble into the garden, or the field, and gather what it thought the prettiest flower it could find, though, perhaps, it might be but a simple weed. The parent would be more gratified by such variety, than if the whole of them had acted on a concerted plan, and each had made exactly the same offering. This would have the cold appearance of contrivance, or the harsh one of control. But of all unwelcome things, nothing could more afflict the parent than to know, that the whole of them had afterwards gotten together by the ears, boys and girls, fighting, scratching, reviling, and abusing each other about which was the best or worst present.

Why may we not suppose, that the great Father of all is pleased with variety of devotion; and that the greatest offence we can act, is that by which we seek to torment and render each other miserable….

It is now towards the middle of February. Were I to take a turn into the country, the trees would present a leafless winterly appearance. As people are apt to pluck twigs as they walk along, I perhaps might do the same, and by chance might observe, that a single bud on that twig had begun to swell. I should reason very unnaturally, or rather not reason at all, to suppose this was the only bud in England which had this appearance. Instead of deciding thus, I should instantly conclude, that the same appearance was beginning, or about to begin, everywhere; and though the vegetable sleep will continue longer on some trees and plants than on others, and though some of them may not blossom for two or three years, all will be in leaf in the summer, except those which are rotten. What pace the political summer may keep with the natural, no human foresight can determine. It is, however, not difficult to perceive that the spring is begun. Thus wishing, as I sincerely do, freedom and happiness to all nations, I close the SECOND PART.

Recommended Readings

- Gregory Claeys, Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought (Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989).

- Eric Foner, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Harvey Kaye, Thomas Paine: Firebrand of the Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Yuval Levin, The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

- Mark Philip, Thomas Paine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Vikki J. Vickers, “My Pen and My Soul Have Ever Gone Together”: Thomas Paine and the American Revolution (New York & London: Routledge, 2006).

Notes

[1] “Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Paine, 19 June 1792,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-20-02-0076-0014 (accessed April 30, 2025).

[2] The Coercive Acts consisted of four laws passed in quick succession: the Boston Port Act (blockade of Boston Harbor); Massachusetts Government Act (local government subject to parliamentary control); Impartial Administration of Justice Act (trials of British officials removed to Britain or other colonies); and Quartering Act (commandeering buildings for the housing of troops).

[3] On the evening of December 16, 1773, Bostonians disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded three merchant vessels loaded with tea and threw their cargo into the harbor.

[4] The Continental Congress met from September 5 through October 26, 1774. It reconvened in May 1775 as the Second Continental Congress. By then, fighting had begun, and this Second Congress remained continuously in session as the effective wartime government of the colonies/states.

[5] England formally changed its name to Great Britain in 1707 when the Acts of Union joined Scotland to England and Wales (joined to England in 1543). England is used here when the reference is to England before 1707 or to England alone; otherwise, Britain or Great Britain is used. Paine used both names interchangeably, irrespective of date and location, while generally preferring England to Britain.

[6] Richard Price, Political Writings, ed. D. O. Thomas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 186.

[7] Ibid., p. 190.

[8] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, ed. Conor Cruise O’Brien (London: Penguin Books, 1986), pp. 102–104. The 1689 English Bill of Rights, which codified the Declaration of Right of earlier that year, stated that “the said Lords Spiritual and Temporal and Commons do in the name of all the people aforesaid most humbly and faithfully submit themselves, their heirs and posterities for ever….” “English Bill of Rights 1689,” Yale University, Avalon Project, http://www.avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/england.asp (accessed March 31, 2025).

[9] Price, Political Writings, p. 98.

[10] Anne, sister of Mary, who was childless, succeeded on the death of William (1702); German-born George I, great grandson of James I by way of granddaughter Sophia, succeeded childless Anne (1714); George II succeeded George I (1727); and George III, king at the time, succeeded George II (1760). So determined were the English to maintain the line of succession that they accepted a non-native, even non–English speaking, distant relative who was nonetheless next in line—or the next Protestant in line, which was an important consideration. An English but Catholic alternative was available: James Francis Edward, son of James II, also Catholic. In 1711, James Francis was approached about assuming the throne after Anne, but the price demanded was renunciation of his Catholic faith. He refused and invaded Britain instead (1715). The attack was repulsed, and James Francis, called the “Old Pretender,” returned to France (1716). His followers were called Jacobites (not to be confused with Jacobins).

[11] Rights of Man, in The Writings of Thomas Paine, coll. & ed. Moncure Daniel Conway, Vol. II (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Knickerbocker Press, 1894), p. 281, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/344/0548-02_Bk.pdf (accessed March 31, 2025).

[12] See, for example, John Locke, “Of Government, Book II,” in The Works of John Locke, Vol. 4 (London: C. Baldwin, Printer, 1824), §§ 95–99, 149, 240, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/763/0128-04_Bk.pdf (accessed March 31, 2025); Jean-Jacques Rousseau, On the Social Contract, with Geneva Manuscript and Political Economy, ed. Roger D. Masters (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1978), III.1, 16.

[13] Magna Carta established the principle of the supremacy of law by placing some limitations on the Crown’s power and securing some rights for the nobility, the Church, and the people. Under pressure from the barons of the realm, King John acceded to the charter on June 15, 1215, at Runnymede.

[14] Rights of Man, in The Writings of Thomas Paine, Vol. II, p. 437. The impulse to start fresh without the encumbrances of the past and guided only by abstract reason was perhaps Paine’s core disagreement with Burke, for whom incremental reform, respectful of the past, provided the surest and safest means of progress.

[15] “Agrarian Justice,” in The Writings of Thomas Paine, coll. & ed. Moncure Daniel Conway, Vol. III (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Knickerbocker Press, 1897), p. 339, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1082/0548-03_Bk.pdf (accessed March 31, 2025).

[16] The Reign of Terror was a period of the French Revolution when the Committee of Public Safety, the country’s de facto government, ordered the arrest and execution of thousands. Although a point of controversy among historians, the usual dates assigned to the Reign of Terror are September 1793 to July 1794, when the Thermidorian Reaction set in (Thermidor denoted a month on the new French calendar).

[17] “Age of Reason (First Part),” in The Writings of Thomas Paine, coll. & ed. Moncure Daniel Conway, Vol. IV (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Knickerbocker Press, 1896), p. 72, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1083/0548-04_Bk.pdf (accessed March 31, 2025).

[18] Ibid., p. 74. Paine seemed to assume that intelligent life exists on other planets: “The inhabitants of each of the worlds of which our system is composed enjoy the same opportunities of knowledge as we do.” Ibid., p. 72.

[19] Deism was a philosophical/theological system of the 17th and 18th centuries especially that espoused the existence of a creator God knowable by empirical reason alone, independent of revelation.

[20] “Dissertation on First Principles of Government,” in The Writings of Thomas Paine, Vol. III, pp. 265–273.

[21] Rights of Man, Part II, in The Writings of Thomas Paine, Vol. II, pp. 515–518.