Sixty years ago, Lee Edwards wrote the following article based upon what he saw in West Berlin. We share it today to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the end of the Soviet Union, whose flag stopped flying over the Kremlin on December 25, 1991.

Mr. Edwards has been traveling in Europe during the month of September, and in place of his regular “Capital” column, sends us an article from West Berlin. The very next day after this writing, he tells us, he will tour East Berlin, “just hoping that it’s melodramatic and nothing else.”

West Berlin, September 12, 1961 – On the sidewalk before 48 Bernauer Strasse in the French sector of this divided city, lie several garlands of flowers mounted with the simple inscription, “In Memorium.” There is no name, but West Berliners know the flower honor an East Berlin woman who jumped from her third-floor apartment seeking freedom. In her nervousness and fear, she missed the mattresses and other bed clothing waiting beneath her and died on the sidewalk within a few minutes.

Across the city in the shadow of the Berlin Hilton, a handsome hotel with its softly shining blue spotlights and penthouse cocktail lounge, West Berliners drink and dance and gambol at the carnival version of their Oktoberfest.

It is possible to visit West Berlin and, providing that you are careful where you go, to be unaware of the Cold War, communism or the closed border between East and West. There are many diversions in this lovely city which has never apologized for its pursuit of pleasure. Off the Kudam in all directions are night clubs and cabarets which present their specialte de la maison until the large hours of the morning (one club opens at 10 PM and closes its doors reluctantly at 10 AM the next day.)

Indeed, sitting on the terrace of Kranzler’s, sipping a cup of delicious coffee and dipping your spoon into a large serving of rich creamy ice cream, it is hard to believe that such unpleasant things as East German Communists exist. But they do. And West Berliners do not deny their existence, despite a seemingly indifferent air.

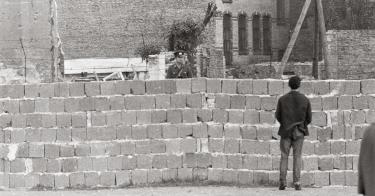

The habitual self-confidence of the West Berliner has been shaken by the five-foot-high concrete wall which has separated East and West Berlin since the middle of August. The barrier, nicknamed the “Chinese Wall” in typically sarcastic fashion, is important for obvious physical reasons. It has cut the torrent of East German refugees to the barest of trickles. It also prevents anything but the sketchiest of contacts between friends and relatives on either side of the border.

Even more telling is the psychological impact of the wall and the implacable way it reminds the West Berliner that he is trapped. Before the erection of the wall he could take great comfort from the “invasion” of great numbers of East German refugees desiring freedom. Now he must squeeze what consolation he can out of the two or three who daily risk imprisonment and death to cross the border.

In addition, many families include members on both sides of the wall. Father and son, mother and daughter may not see each other for months or years or forever. In such an uncompromising situation, it is only natural that West Berliners seek amusement and distraction. But all the while they wait for the next turning of the screw by the Soviets and their puppets, the East German Communists.

The most obvious Soviet move would be to cut off access by air. At present there are three air corridors into the city through which commercial airlines such as Pan American, Air France and British European Airways send 200,000 flights annually. Several tentative harassments have already been executed. Some pilots have complained about static interference with their radios on their approach to Berlin. Others have commented that large East Berlin searchlights have distracted them on their crossing East Berlin preparatory to landing.

Recently a prominent East German Communist asserted that after the final treaty with the Soviet Union has been signed, all commercial airlines will have to deal directly with the East German Communist Government (he used the euphonious phrase, “German Democratic Republic”). Without the comforting sound of airliners passing only a few thousand feet overhead, West Berliners would indeed be isolated.

The city, however, is prepared. Under the direction of Mayor Willy Brandt, West Berlin has stocked months and even years of food staples and supplies. But the city is not self-supporting and could not endure without assistance from the outside.

Meanwhile, in a Teutonic variation of que sera, sera, West Berliners build and plan for tomorrow, and the new and old stand side by side as in so many West German cities. Two hundred farms still exist within the city limits, which include 346 square miles, making Berlin the third largest city in area in the world. It would take you seven days to walk around its circumference (assuming you could persuade the East German Communist guards who encircle the city to approve such a trip).

But always, on any tour, your attention is drawn to the “Chinese Wall,” 30 miles long, covering every inch of the border (except directly under the Brandenburg Gate) between East and West Berlin.

The French sector (it is necessary to remember that West Berlin is not part of the West German Federal Republic but still under Allied Trusteeship) has been the scene of most of the spectacular escapes. It is here that East and West literally meet without a “no man’s land” as exists in the British and American sectors. The woman who jumped from the third floor lived in an East Berlin apartment, but the street on which she died was in West Berlin. Here on a weekend West Berliners will gather to wave colored handkerchiefs or signal with umbrellas to friends or relatives a few hundred feet away. Here an old man will yell a few words of encouragement to a friend leaning out of a second-floor window (the wall runs along the street level and everyone and everything have been moved out of the first floor). Here East and West Berliners relieve their frustration under the eyes of the East German police (wearing rifles) and West German police (wearing pistols).

A West Berliner said bitterly as he stared east over the wall:

“Look—there you see the biggest concentration camp in the world, 16 million people, and among them, my own parents.”

Yes, and yet, what is he living in? If the United States and its allies do not stand firm, the concentration camp will soon add another two million inmates who presently live in West Berlin.

This piece originally appeared in Providence Magazine