The Caspian Sea is an important, if often-overlooked, region for the United States. Many of the challenges the U.S. faces around the world, such as a resurgent Russia, an emboldened Iran, a growing China, and the threat of Islamist extremism, converge in the Caspian region. The Caspian Sea is at the heart of the Eurasian continent and is a crucial geographical and cultural crossroads linking Europe and Asia that has proven strategically important to many countries for military and economic reasons for centuries.

The U.S. needs to develop a strategy for engagement in the region that promotes economic freedom, secures transit and production zones for energy resources, and is aware of the consequences of increased Chinese, Iranian, and Russian influence in the region that are working against Western interests.

The U.S. should have a frank, open, and constructive dialogue with its allies in the region about human rights issues—with the goal of long-term democratization. However, human rights should be just one part of a multifaceted relationship that considers broader U.S. strategic interests and stability in the region. If the U.S. pursues the correct policies, it can help to ensure that the countries in the region are stable, sovereign, and self-governing.

The Caspian Sea: An Overview

The Caspian Sea is the world’s largest inland body of water and accounts for 44 percent of the world’s lacustrine water. There are five Caspian littoral states: Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan.

The Caspian Sea is connected to the outside world by the Volga River and two canals that pass through Russia: the Volga–Don Canal, which links the Caspian Sea with the Sea of Azov, and the Volga–Baltic Waterway, which links the Caspian Sea with the Baltic Sea.REF There is also a proposal to create a Eurasia Canal, which would transform the Kuma–Manych Canal (currently only an irrigation canal) into a shipping canal that would link the Caspian Sea and Black Sea.REF If ever realized, this would be the shortest route from the Caspian Sea to the outside world.

The Caspian is located between Europe and Asia, two major energy-consuming markets. Billions of dollars are being invested to connect the region to the rest of the world. Like spokes on a wheel, new and modernized roads and rail lines are being constructed connecting the Caspian to East Asian, Europe, and India.

The resources located in and near the Caspian make the region of particular importance to locals and outsiders alike. The region has an estimated 48 billion barrels of oil and 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in proved and probable reserves.REF In addition to oil and gas, the region is also home to more than 100 species of fish. Most important is the European sturgeon, which is listed as “critically endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.REF The vast majority of the black and red caviar sold globally comes from the Caspian. However, decades of overfishing and large-scale pollution threaten the region’s fishing sector.REF

The Caspian region is religiously diverse and home to thriving Buddhist, Orthodox Christian, Jewish, and Muslim populations. The Ateshgah of Baku in Azerbaijan (commonly referred to as the Fire Temple of Baku) served as a Zoroastrian temple and was a pilgrimage destination for Hindis and Sikhs as far away as India. Today, small pockets of Hindus and Zoroastrians still live in the region.

With the exception of Iran and the Republic of Dagestan—a federal subject of Russia, which accounts for two-thirds of Russia’s Caspian shoreline—Islamist extremism has not established roots in the Caspian region like it has in the Middle East and North Africa, mainly due to do the secular nature of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.

The regional powers have contested control of the Caspian for centuries. The region is trapped between two former imperial powers: Iran and Russia. Turkey, a regional power, also exerts significant influence for historical and cultural reasons even though it is not a Caspian littoral country.REF

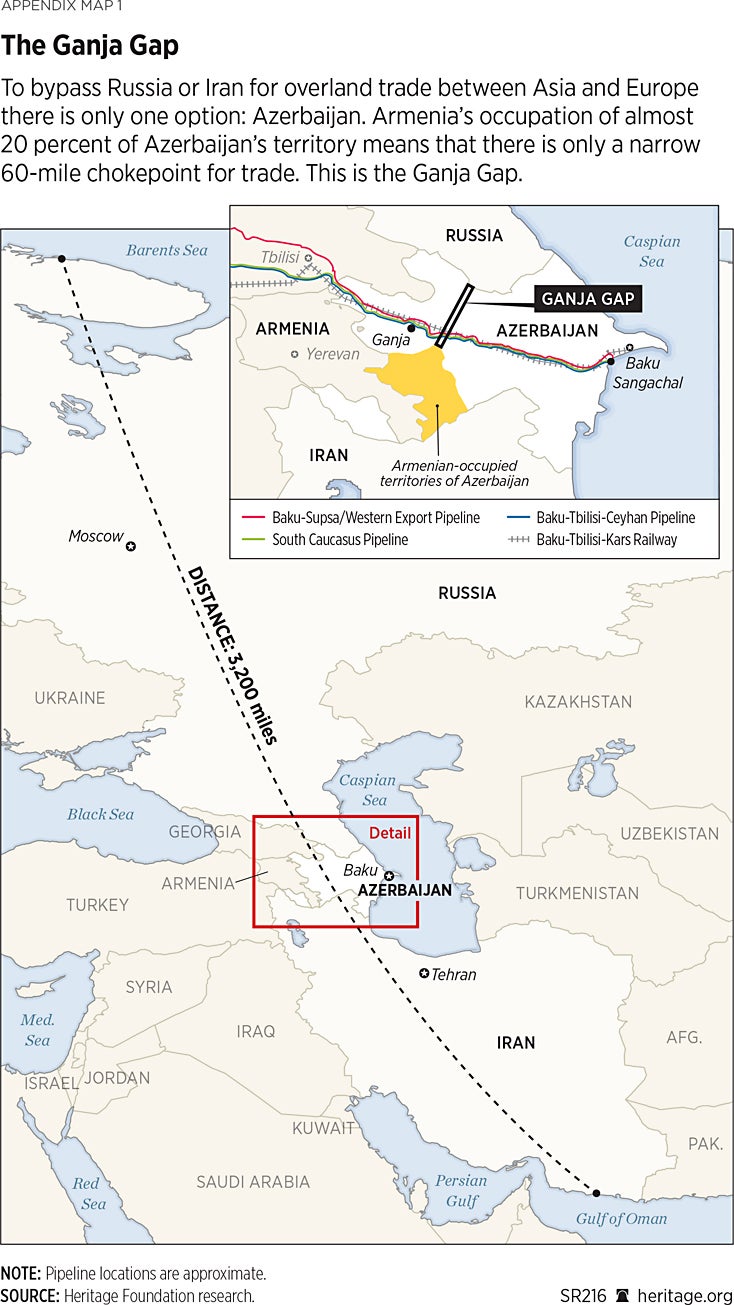

The Caspian is in a rough neighborhood. Certain regions of the North Caucasus in southern Russia have been used as recruiting and transit zones for terrorist groups, such as the so-called Islamic State (ISIS). Iran continues to be a destabilizing force in the region. Armenia continues to occupy almost 20 percent of Azerbaijan, and fighting between the two has been known to flare up from time to time. Due to the lack of U.S. engagement in the region, traditional American partners have been cozying up to Russia. China has been courting Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan more than ever before, although it has been less welcomed on the western shores of the Caspian.

Iran and Russia are the region’s biggest players. Yet in many ways Azerbaijan, Kazahkstan, and Turkmenistan are also emerging regional actors. As Iran and Russia become increasingly distracted by events outside the region (Syria and Ukraine), the roles of these three Caspian countries will likely become more pronounced—in the region and beyond.

Today, more outside actors are in the region than ever before. The U.S. showed strong interest in the region immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and then again after 9/11, but has recently placed the region on the back burner. The 2017 National Security Strategy runs 55 pages long and does not mention the word “Caspian”; it makes substantial mention of Central Asia only once, in a sentence focused on counterterrorism.REF

China has long been looking for new economic and energy opportunities, and this remains its main motivation in the region today. Europe is also involved economically and with energy projects but has little influence in the region. This is extremely shortsighted—and indeed a paradox—considering the economic and energy potential the region could offer Europe.

U.S. Interests in the Caspian Region

For the U.S., the Caspian region is a place where challenges and opportunities converge. On the one hand, the region is prone to many of the problems the U.S. faces around the world: a resurgent Russia, an emboldened China, a meddling Iran, and the rise of Islamist extremism. On the other hand, there are many economic opportunities for the U.S. and Europe: Close cooperation with regional countries can help solve larger problems, such as the situation in Afghanistan and the fight against terrorism, and oil and gas from the region can help reduce Europe’s dependence on Russia.

Unlike many of the other actors in the Caspian, the U.S. is a relative newcomer to the region. Today, U.S. interests in the Caspian region derive primarily from its security commitment to Europe’s members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the war against transnational terrorism, and the desire to balance Chinese, Russian, and Iranian influence in the region.

U.S. policymaking in the Caspian region often falls victim to administrative and bureaucratic divisions within the U.S. government. For example, the Caspian is divided amongst three different bureaus in the State Department: (1) The Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs covers the countries on the western shore of the Caspian, including Russia and Azerbaijan; (2) the Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs covers the eastern shore, including Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan; and (3) the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs handles Iran. There are similar administrative barriers in the National Security Council and with Department of Defense Combatant Commands.

This situation tends to lead to an incoherent attempt at cross-government policy for the region.

To deal with this challenge, the George W. Bush Administration appointed a Special Envoy for Eurasian Energy, who had a specific focus on the Caspian region, but this position has been left unfilled since March 2012.

America’s primary goals for the Caspian region can be summed up with five “s” descriptions: sovereign, secure, self-governing, secular, and settled. In the Caspian region, the U.S. needs:

- A sovereign Caspian. Across the Caspian region, national sovereignty is being undermined by illegal occupation. Between Armenia’s occupation of Nagorno–Karabakh and Russia’s occupation of Georgia’s Abkhazia and Tskhinvali region,REF there are an estimated 10,000 square miles of territory under illegal occupation in the broader Caspian region. Many of the region’s important pipelines, highways, and rail lines run within mere miles of these areas of occupation. Furthermore, these frozen conflicts are how Moscow exerts most of its influence in the region. The U.S. should support policies and initiatives that would help end these occupations and bring stability to the region.

- A secure Caspian. The U.S. should promote policies in the Caspian region that support regional security. A secure Caspian region offers many economic, trade, and energy opportunities. Assisting the Caspian in becoming a stable and secure transit and production zone for energy resources will greatly benefit America and its allies. A secure Caspian will also encourage much-needed foreign investment in the region.

- A self-governing Caspian. It is in America’s interests that Caspian countries remain self-governing with little or no influence from outside or regional powers. This is particularly true of Russia’s maligned influence and hybrid tactics in the region. Strong and stable governments resilient to outside influence are in America’s interest in the region.

- A secular Caspian. With the exception of Iran and the Republic of Dagestan—a federal subject of Russia, which accounts for two-thirds of Russia’s Caspian shoreline—radical Islamist movements have not established a presence in the Caspian region like they have in the Middle East and North Africa. This is mainly due to do the secular nature of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. It is in America’s interest that the situation remains this way.

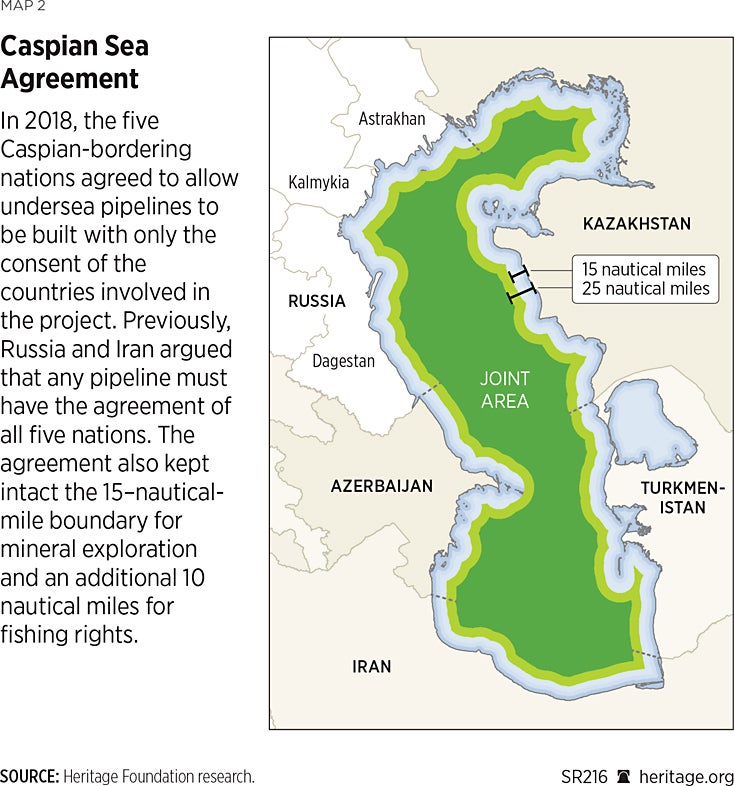

- A settled Caspian. After 22 years, 52 working group meetings, and five Caspian Summits, the leaders of the five Caspian nations signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in 2018.REF This agreement paves the way for the completion of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline, potentially linking Central Asian energy markets with Europe, bypassing Iran and Russia. While this agreement outlines how and by whom the Caspian can be used, it fails to address many of the delineation issues in the Caspian that have been the source of tension in recent years. It is in America’s interest that these bilateral disagreements regarding the delineation of the Caspian be resolved.

Even with these five very important goals, U.S. engagement in the region remains minimal. With Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, one of the biggest challenges facing Washington is the perceived transactional nature of relations between them and the United States.

By the late 1990s, the U.S. had lost much of its enthusiasm for its engagement with the Caspian region, which had followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. Immediately after 9/11, the U.S. sought to re-engage with the region to secure transit and basing rights for operations in Afghanistan. Some countries in the region sent troops to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan, opened transit routes, and offered basing support to the U.S. and NATO. While the countries in the region were looking for a long-term relationship, once the Afghan drawdown began in 2014 and the U.S. pulled back from the region, it became clear that the U.S. was not interested in building enduring relations.

The transactional nature of America’s relationship with regional countries is shortsighted for two reasons: First, it creates the perception with countries in the region that as soon as the U.S. gets what it wants, it will move on. Second, it diminishes any goodwill that the U.S. creates in the region. Considering how important the region is to a broader Eurasia strategy dealing with Russia and Iran, this will have negative consequences for U.S. policy.

In light of President Donald Trump’s Afghan strategy, the region could become very important once again for the United States. A key plank of the Administration’s Afghan strategy is pressuring Pakistan to end its support for the Taliban and associated groups.REF A consequence of this approach with Islamabad might be that the ground and air resupplies transiting Pakistani territory could be cut or stopped altogether. If this happens, the Caspian region could become very important for the U.S. military effort in Afghanistan.

Outside the context of Afghanistan, the Obama Administration had little meaningful engagement with the Caspian region other than setting up the “C5+1” dialogue.REF In 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Azerbaijan. In November 2015, Secretary of State John Kerry visited all five countries in Central Asia, including the Caspian states of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. However, nothing marked a major change in U.S. policy toward the Caspian region.

The Trump Administration, distracted by domestic issues, has not formulated an apparent strategy for the region, and U.S. engagement remains minimal. On a positive note, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson held a C5+1 meeting in New York City during the United National General Assembly meeting in 2017.REF At a minimum, this shows that the U.S. is continuing this Obama-era initiative—which is generally viewed as positive. National Security Advisor John Bolton visited Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital, in 2018.REF Energy Secretary Rick Perry was scheduled to visit Kazakhstan in 2017, and his trip was abruptly canceled due to a major hurricane hitting Texas.REF However, other high-level visits to the region from the Trump Administration have not occurred.

Over the past decade, there have been several events that have dampened U.S. relations in the region and forced Caspian countries to hedge their bets with closer ties with Russia:

- The perceived lackluster U.S. response to Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia. After the invasion, policymakers in and across the Caspian started to question American power and influence in the region.

- The U.S. drawdown in Afghanistan and the subsequent disengagement in the region. There is a feeling that the U.S. got what it wanted for the war in Afghanistan, and that now the U.S. no longer needs the countries in the region as a partner.

- The Western response to Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea and eastern Ukraine. These events made the U.S. and the West look weak in a part of the world where strength and power are respected.

- The mixed messages coming from the West when it comes to Russia. Regional countries are expected to tow a tough line with Russia but see Europe divided on economic sanctions, Germany driving ahead with Nord Stream 2, and flowery language regarding a possible rapprochement from the Trump Administration since the Mueller ReportREF was published.REF

As a result, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are more cautious and mindful of their place in the region. Globally, they are trying to keep a balance in their relations with the West and Russia. Regionally, they are trying to keep a balance between Russia and Iran while striving to preserve their autonomy or independence as much as possible.

U.S. Maritime Interests in the Caspian Sea

While none of the Caspian countries are in NATO, and therefore none receive security guarantees, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are members of NATO’s Partnership for Peace program.REF To varying degrees, all have helped NATO operations in Afghanistan: Turkmenistan probably the least; Azerbaijan, the most (currently maintaining 90 soldiers for the NATO-led operation there). In recent years, Kazakhstan has played an important diplomatic and economic role in Afghanistan.REF

Although located several thousand miles away, the United States has maritime interests on the Caspian Sea. Due to the landlocked nature of the Caspian and the limitations placed on the role of outside foreign powers in the region, the U.S. Navy has never sailed on the sea, nor are there any plans to do so. The Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, signed by all five littoral states in August 2018, bans foreign warships from the Caspian. However, this should not prevent the U.S. from promoting its maritime interests in the region by other means.

Since the U.S. cannot have a naval presence on the Caspian,REF the number one priority of the U.S. should be building the maritime capabilities and capacities of friendly Caspian states. At the top of the list are Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. However, there is scope for cooperation with Turkmenistan, too.

When it comes to improving the maritime capability of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, the U.S. has strategic and tactical goals. Regarding the maritime situation, the main strategic goal should be for the U.S. to help partners in the region maintain a balance of power amongst all five Caspian powers so that one country (Iran or Russia) does not have overwhelming maritime power in the region. It is unrealistic to believe that a single Caspian state will ever match the firepower of Russia. This should not be the goal. Instead, U.S. policymakers should strive to help friendly countries in the region mitigate, balance, and deter any possible Russian and Iranian malign activity. Ultimately, this approach will bring stability to the region.

Regarding the maritime situation, the main tactical goal in the Caspian Sea for the U.S. should be to help friendly countries secure their maritime borders, protect vital energy infrastructure, stop the flow of terrorists, prevent terror attacks, ensure the free flow of commerce in the region, and prevent the transfer of illegal weapons and drugs.

Since the U.S. Navy will likely never have a presence on the Caspian, the U.S should provide training opportunities, officer exchanges, and equipment modernization wherever possible. This used to be the approach of the U.S., but in recent years resources for such programs have dried up and U.S. security interests have waned.

Between 2000 and 2003, the U.S. Coast Guard gave three cutters to Azerbaijan. These ships traveled from the West Coast of the U.S. to Azerbaijan via the Black Sea, Sea of Azov, and the Volga-Don canal to the Caspian Sea. In addition, the U.S. supplied Azerbaijan’s naval vessels with radar and communication equipment to help improve command and control. One of the biggest capability gaps of Azerbaijan in the Caspian is maritime domain awareness, so the U.S. has also provided a number of coastal radar stations, which, according to the U.S. State Department, are used “by the Navy, Coast Guard, and State Border Service to conduct maritime surveillance and detect smuggling threats.”REF Over recent years the U.S. has provided similar assistance to Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, albeit on a much smaller scale.

As a way to institutionalize naval cooperation on the Caspian Sea, the U.S. started the Caspian Guard Initiative (CGI) in 2003. At the time, the CGI was described as “an initiative which established an integrated airspace, maritime and border control regime for the nations of Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan.”REF The lead combatant command for the initiative was the European Command (EUCOM), but one of the main reasons why the CGI was created was to coordinate efforts across different agencies of the U.S. government. This was especially true regarding U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), which has the eastern shore of the Caspian in its Area of Responsibility.

In 2006, then-Commander of EUCOM, General Jim Jones, told the U.S. Congress about the EUCOM Posture Statement and that the:

CGI assists Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan in improving their ability to prevent and, if needed, respond to terrorism, nuclear proliferation, drug and human trafficking, and other transnational threats in the Caspian region. With CENTCOM [CGI works] with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Department of State, the Department of Defense (Under Secretary of Defense for Policy), and the Department of Energy to improve Azerbaijan’s and Kazakhstan’s capacities. As a result, U.S. government “stakeholders” know their contributions are part of a coherent, strategic effort that promotes interoperability among activities, identifies capability gaps and cooperation opportunities, and mitigates redundant and duplicative efforts. CGI-related projects in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan include maritime special operations training, WMD [weapons of mass destruction] detection and response training and equipment, naval vessel and communications upgrades, development of rapid reaction capabilities, border enhancements, counter-narcoterrorism and border control training, naval infrastructure development planning, and inter-ministry crisis response exercises.REF

Sadly, what started out as an ambitious project soon faded away. There are two likely reasons for this. First, regional countries did not like the newfound scrutiny that was placed on them in Washington because of the increase in U.S. funding. Second, pressure from Moscow and Tehran on Ashgabat, Baku, and Nur-SultanREF was more than the regional capitals were willing to tolerate and this forced the initiative to end. If the U.S. were to ramp up its maritime support to the region again, it is likely that the three U.S. partners would come under the same pressures—especially in light of the recently agreed Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea.

Regardless, most analysts will agree that the U.S. has lost focus on the region generally, and on the maritime situation in the Caspian specifically. In the 2019 EUCOM Posture Statement, which is nearly 5,600 words long, the current commander of U.S. EUCOM General Curtis Scaparrotti did not mention the word “Caspian” once.REF This is very different from General Jones’ comments in 2006.

The challenge for the U.S. will be to stay within the framework of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea (which should be easy as there is no desire to deploy U.S. ships on the Caspian) while making the offer of support too good for the regional countries to turn down. It remains to be seen if the U.S. has the political will to do so.

Outside Actors in the Caspian

The Caspian will continue to be a strategic chessboard for regional and global powers well into the future. China, Europe, and Turkey are active in the region.

The region is important for Europe. If the Europeans are to achieve any significant energy diversification away from Russia, it would likely be through the Caspian. Therefore, the Caspian region threatens Russia’s role as a major energy supplier and, by extension, Moscow’s political influence over Europe.

The desire to secure alternative sources of energy is at the heart of European engagement in the Caspian. Yet, paradoxically, the European Union has little influence in the region and does not seem intent on changing this. Out of a total of 17 pages, the EU Commission’s 2019 Central Asia strategy devoted only half a sentence to the critically important issue of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline. The whole document only mentions the word “Caspian” twice.REF

The EU’s dealings with Russia and Iran focus on issues of global importance, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the fate of the Iran deal. Rarely does the EU show a willingness or desire to focus on Caspian-specific issues. In its relations with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, the EU seems more interested in pushing its normative values in the region than securing alternative sources of energy.

When energy is discussed, there is often a disproportionate focus on renewable energy resources in the region. For example, in the EU’s new Central Asia strategy there are no fewer than six different references to “renewable” or “sustainable” energy, while the words “oil” and “gas” are not found at all.REF For a region that derives much of its revenue from oil and gas, this shows a certain disconnect between the EU’s priorities for the region and what is actually happening on the ground.

Turkey’s influence in the Caspian region derives primarily from its cultural, linguistic, and economic links with the three ethnically Turkic countries of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. In particular, Ankara has very close relations with Baku. With their short nine-mile shared border, Turkey provides a lifeline to Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, an Azerbaijani exclave that is geographically surrounded by Armenia and Iran. Turkish companies have invested billions of dollars in the region.

Ankara has shown a willingness to flex military muscle in the region, too—especially when it comes to looking after its fellow Turkic compatriots. In July 2001, Iranian naval vessels and an Iranian fighter jet entered Azerbaijani waters in the Caspian and harassed an Azerbaijani surveying operation. Turkey responded by sending F-16 fighters to Baku and dispatching the head of the Turkish army to the capital.

China has invested heavily in a number of infrastructure projects in Central Asia as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. Most of China’s activity has taken place on the eastern shore of the Caspian. Major port, pipeline, and infrastructure projects on the Caspian’s western shore have been done without much, if any, Chinese involvement.REF

For the foreseeable future, China’s activity in the Caspian will be a continuation of Beijing’s policy of pursuing its economic interests wherever in the world it might be. Moscow is already keeping a close eye on Beijing’s motives in the region and views Beijing as a potential competitor for influence in the region in the same way that Russia sees Iran.

Beyond a doubt, Russia and Iran are the two biggest actors in the region.

Russia and the Caspian. Russia first became active in the Caspian region in the 18th century. During the subsequent years of Russian domination over the region, Moscow occasionally shared influence in the Caspian with the Persian Empire. After a series of military defeats to Russia, Persia all but relinquished its last vestiges of influence in the Caspian. By the late 19th century, the Caspian Sea was essentially a Russian lake.

Despite the breakup of the Soviet Union and the independence of the other three Caspian littoral states (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan) in 1991, Russia still sees itself as a leader in the region.

Today, Russia maximizes influence in the region by economic, diplomatic, and military means. Russia maintains the largest naval fleet on the Caspian Sea. Russian businesses and foreign investment are found in every Caspian country. Russian-backed organizations, such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)REF and Eurasia Economic Union (EEU),REF attempt to bind regional capitals to Moscow through a series of agreements and treaties, with mixed success.

The goals of Moscow in the Caspian today and for the foreseeable future are to:

- Marginalize Western influence in the region. This is especially true of the U.S., EU, and NATO. Russia has generally succeeded. U.S. influence in the region is at an all-time low, and the EU has not completed the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline, one of its main priorities in the region. As an institution, NATO has very limited relations with countries in the region.

- Integrate the countries in the region into Russian-backed organizations. Russia has had limited success with the former Soviet states in the region, and less with Iran. Kazakhstan is a member of the CSTO. Azerbaijan left the organization in 1999, and Turkmenistan and Iran never joined. Only Kazakhstan is in the EEU. Only Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan are in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).REF Russian-inspired ideas, such as the creation of a joint Caspian naval force, have been met with skepticism by other Caspian countries.

- Discourage outside investment in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan that could facilitate the flow of oil and gas to Western markets by bypassing Russia. This goal is probably the most important for Russia. The Kremlin mentality is that if Europe is not buying oil and gas from Russia, it should not buy them from anywhere else in the region. Moscow pursues policies in the Caspian region that limit and, if possible, block oil and gas transiting through the region to Europe.

- Increase economic activity with the other Caspian states. Russia’s trade with Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan came to $33 billion in 2013.REF Moscow’s desire to increase trade in the region is the main driver for several Russian-inspired transportation infrastructure projects in the Caspian—especially in light of Western sanctions over Ukraine.

- Maintain regional hegemony over Iran. When economic sanctions against Iran are lifted or reduced, Iran will likely become more assertive in the region, no longer needing to rely on Moscow’s support on the international stage. This could become a future source of friction with Russia. For now, as historical rivals in the Caucasus and Central Asia, Russia wants to check Iranian influence in the region, but this takes a back seat to Russia’s desire to keep Western influence out.

Russia also faces many internal challenges in the region. The Russian shore of the Caspian is ethnically and religiously diverse. The city of Astrakhan in the Astrakhan Oblast has played an important role in the region’s history and is still at the center of Russian economic activity in the Caspian. While oil production across Russia’s Caspian region has declined in recent years, production has actually increased in the Astrakhan Oblast.REF

To the west of the Astrakhan Oblast is the semi-autonomous Republic of Kalmykia. Kalmykia is home to the largest Buddhist Temple in Eurasia and is the only region in Europe where Buddhism is practiced by a plurality of its citizens.REF It is also one of the poorest regions in Russia.REF There are two main oil fields off Kalmykia’s coast, but the region produces the least amount of oil and gas of Russia’s Caspian region.

To the southwest of the Republic of Kalmykia is the semi-autonomous Republic of Dagestan. It has an estimated one-third of the Caspian’s oil, and just under half of its natural gas is within 100 miles of the shore. Dagestan accounts for two-thirds of Russia’s Caspian shoreline.REF Therefore, for oil and gas, Dagestan is Russia’s most important region in the Caspian. Dagestan has 20 oil and gas fields and an important oil refinery in Makhachkala, the republic’s capital and an important port on the Caspian that serves as a key transit point for oil produced in the Russian section of the Caspian Sea.REF

Russia’s Caspian region is also fraught with political, religious, and ethnic tensions and instability. Located in the North Caucasus as well as the Caspian region, Dagestan’s population is predominately Sunni Muslim, and Makhachkala is the home of one of Russia’s largest mosques. The North Caucasus is the region’s powder keg and has a long history of defiance toward Moscow. There are legitimate concerns about the region’s long-term stability. Islamist terrorists from the self-proclaimed Caucasus Emirate have already attacked energy infrastructure, trains, planes, theaters, and hospitals across Russia, and have sent foreign fighters to the so-called Islamic State.

In an attempt to reduce the hostilities, the Russian government implemented many economic and developmental programs and provided billions of dollars in aid to the North Caucasus. However, with the drop in oil prices, the impact of economic sanctions, and the subsequent need to reduce spending, funding for the region has been generally reduced in recent years. Chechnya is the exception.REF

Neighboring Chechnya is another threat to stability in Dagestan. Historically, instability and conflict in Chechnya destabilizes or spills into Dagestan, just as it did in 1818 with the building of a Russian fort in Grozny (now the capital of Chechnya), the insurgency led by Imam Shamil in the middle of the 19th century during the Caucasian War, and more recently during the two Chechen Wars in the 1990s and early 2000s. A deteriorating security situation in Chechnya could affect Dagestan and would seriously jeopardize Russia’s oil and gas production in the Caspian region.

Russia also sees the Caspian Sea as a strategic asset. Over the past decade there have been several large-scale military training exercises in the region, some unilateral, others multilateral. Moscow is investing in new barracks and other basing infrastructure in the Caspian for its navy there. Russia’s Caspian Flotilla is soon receiving an expanded and upgraded air squadron.REF

Russia has even used warships operating in the Caspian to conduct cruise-missile strikes against targets in Syria almost 900 miles away.REF It is worth pointing out that this use of Caspian-based naval assets to strike targets in Syria had less to do with achieving military effects than it did with Caspian geopolitics. These missile strikes sent a strong signal to the other Caspian countries that Russia is the dominant military power in the region.REF However, while Russia maintains the largest naval presence in the Caspian, the other littoral countries have also been investing in new ships, anti-ship missiles, and submarines.

The importance that Russia places on the Caspian can also help explain, at least in part, its determination to occupy Crimea and fully control the Sea of Azov. One of the two canals connecting the Caspian to the outside world is the Volga–Don Canal, which links the Caspian Sea with the Sea of Azov. In the past year Russia has been using the Volga–Don Canal more often to move warships between the Caspian Sea and the Sea of Azov,REF and has even wanted to expand the canal systems connecting the two bodies of water.REF An incident in late 2018, when Russia captured 24 Ukrainian sailors in international waters near the Kerch StraitREF (connecting the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov), demonstrated the lengths to which Moscow will go in order to preserve its influence in the Sea of Azov.

Moscow has long sought to control the flow of oil and gas to Europe and has never liked pipelines that bypass Russian territory to transport oil and gas to Europe. To this end, where Europe is able to import from other sources, Russia has shown that it can easily pose an indirect risk to its supply.

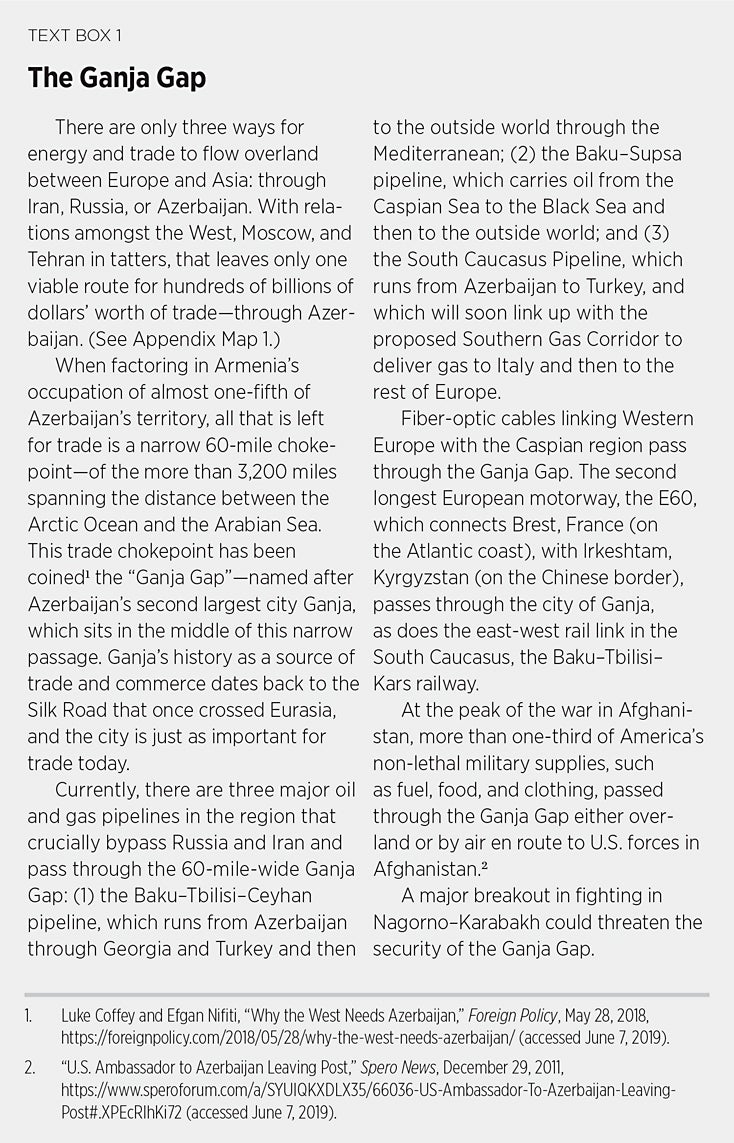

For example, at their closest points, the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), and the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) railway run within about eight miles of the Line of Contact between Armenian-occupied Nagorno–Karabakh and Azerbaijani forces.REF During the 2008 Russian invasion of Georgia, the SCP and BTC pipeline temporarily stopped operations due to the conflict. In 2014, Russia also annexed a small chunk of Georgia that places a one-mile segment of the BP-operated Baku–Supsa pipeline, which transports oil from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea, inside Russian-occupied territory.REF The ability to disrupt Europe’s oil and gas flow from the Caspian merely by increasing local tensions helps Russia ensure that the conflicts in the South Caucasus are not resolved anytime soon.

Iran and the Caspian. Iran is one of the established Eurasian powers and therefore sees itself as entitled to a special status in the Caspian region. While Iran competes with Russia for influence in the Caspian, Tehran also shares many goals with Moscow, such as keeping foreign influence—especially the U.S.—out of the region. The two countries cooperate closely in Syria. Russia provides diplomatic top cover at the U.N. Security Council for Iran’s nuclear program. The Russian and Iranian navies conduct joint military exercises.REF The two have discussed an oil-swap agreement that would help Tehran skirt U.S. sanctions.REF

The southern part of the Caspian Sea, which includes the Iranian section, is very deep and accounts for two-thirds of the sea’s total volume of water.REF Oil and gas exploration and extraction in this section is extremely challenging. This will remain the case until technological advances are made.

Iran holds almost 10 percent of the world’s crude oil reserves and 17 percent of the world’s proved natural gas reserves, giving it the second largest natural gas reserves in the world, behind Russia. About 71 percent of Iran’s crude oil reserves are located onshore, with the remainder mostly located offshore in the Persian Gulf.REF Like Iran’s oil reserves, Iran’s natural gas reserves are also located away from the Caspian region. It is estimated that Iran has 500 million barrels of proved and probable reserves in the Caspian Sea.REF Since the depth of the Caspian in Iran’s sector makes it difficult to extract oil, and with the impact of U.S. sanctions, production in the region has been minimal.

With the majority of Iran’s energy production far removed from the Caspian, Tehran’s interest in the region derives more from history and culture than from oil and gas. Luckily for the region, Iranian exports of its radical brand of Shia Islam have been less effective in the Caspian region than in the Middle East.

Although Iran occasionally meddles in the internal affairs of Azerbaijan, Tehran has come to realize that it cannot influence the Caspian region with religion as it does other parts of the world. Modern Iran does not appeal to the Muslims living to its north in the same way the Persian Empire once did. Most Muslim Turkmen in Central Asia are secular and are put off by Tehran’s fundamentalism. Regime oppression in Iran stifles the cultural appeal that Persian literature, music, and cinema once held in the region. Until the Iranian regime’s attitudes change or the regime changes, this will continue to be the case. Azerbaijan is perhaps the best example of this.

Azerbaijan is one of the predominately Shia areas in the world that Iran has not been able to place under its influence. Azerbaijanis reject Tehran’s brand of extreme Islam and embrace religious freedom and secularism. Azerbaijan’s close relations with Israel are perhaps the manifestation of Baku’s rejection of Tehran’s influence.

Iran has coordinated and backed a number of high-profile terrorist events inside Azerbaijan, further souring relations between the two countries. In March 2012, Azerbaijan arrested 22 people hired by Iran to attack the U.S. and Israeli embassies in Baku. A few months prior, Azerbaijani security services prevented an Iranian-backed attack on a Jewish school in Baku.REF

Even with the underlying religious friction, Iran and Azerbaijan maintain cordial, if at times tense, relations. Iran disputes many of Azerbaijan’s Caspian claims and has even used its navy to interfere with energy exploration operations.REF

Iran’s closeness with Azerbaijan’s archenemy Armenia also makes Baku nervous. During the war in the Nagorno–Karabakh in the early 1990s, Iran sided with Armenia as a way to marginalize Azerbaijan’s role in the region. Last year Armenian–Iranian trade hit a record high.REF As Yerevan and Tehran cooperate more closely, Baku will remain nervous.

The Eastern Shore: Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan

On the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea are Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have enjoyed one of the warmest bilateral relations of the Central Asian states and share many challenges in the region,REF including the need to balance their relations among China, Russia, and the U.S.

Kazakhstan: In the Heart of Eurasia. In 2020, Kazakhstan will celebrate the 555th anniversary of the founding of the Kazakh Khanate, which is considered the foundation of modern-day Kazakhstan. Although dominated by Russia for almost 200 years, since regaining its independence in 1991, Kazakhstan has developed its own regional policy that tries to be distinct from Russia’s policy. Even so, Nur-Sultan retains close ties with Moscow through membership in the Russian-backed EEU and the CSTO. Kazakhstan joined the World Trade Organization in 2015.

Kazakhstan, the world’s ninth largest country by land mass, sits right in the heart of Eurasia and has the longest Caspian coastline of all five littoral states. It is a major hydrocarbon player and has the potential to help Europe alleviate some of its hydrocarbon dependence on Russia. In addition, major transit routes pass through Kazakhstan along the old Silk Road, connecting East Asia with Western Europe.

Kazakhstan is undergoing drastic political change. Nursultan Nazarbayev, who served as the first president of Kazakhstan since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, still plays an important role behind the scenes. In June 2019, presidential elections were held, and the former chairman of the Senate, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, won 70 percent of the vote.

Nearly 25 percent of Kazakhstan’s population of 17 million are Russian. Most of the Russian population live along Kazakhstan’s 4,250-mile border with Russia. After Russia annexed Crimea in early 2014, some in Kazakhstan became nervous that parts of their country might be next. Provocative comments by senior officials in Moscow have heightened this fear. In 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin even suggested that the “Kazakhs had no statehood”REF until Nazarbayev came to power.

As the largest economy in Central Asia, Kazakhstan attracts most of the region’s trade and investment. The economies of Kazakhstan and Russia are closely linked, so Western economic sanctions on Russia have had a negative trickle-down effect in Kazakhstan.

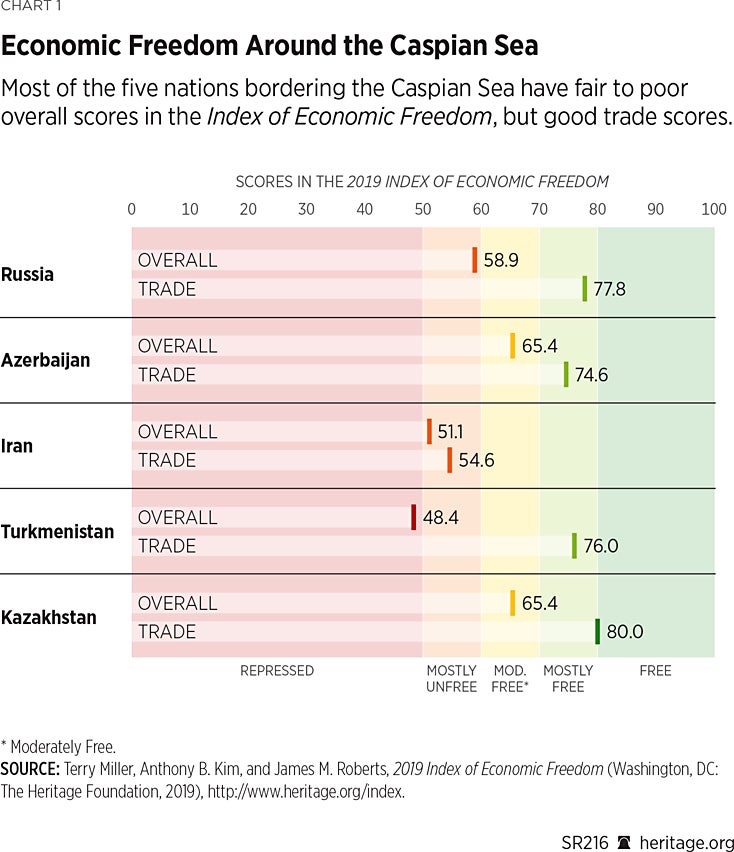

Nazarbayev called for the creation of a free trade zone among the countries of the Caspian Sea, but the climate of mistrust that plagues the region makes this unlikely to happen anytime soon.REF Of the five Caspian countries, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan rank the highest in the Caspian region for economic freedom according to the 2019 Index of Economic Freedom, published by The Heritage Foundation.REF

Kazakhstan has been an oil producer since 1911, and is the second largest oil producer in the post-Soviet space, after the Russian Federation. Over the years, Kazakhstan has enjoyed modest economic prosperity and stability based mostly on exploitation of its abundant mineral wealth, primarily hydrocarbons, but also ferrous and nonferrous metals—including uranium. Kazakhstan is the world’s largest producer of uranium.

For the U.S., there are many reasons to maintain good relations with Kazakhstan. For years, Kazakhstan has been a leading voice for the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons, having given up hundreds of nuclear weapons it inherited after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Like Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan is a Muslim-majority country, and is staunchly secular in its politics, maintaining cordial relations with all countries in the Middle East—from Israel to Saudi Arabia to everyone in between.

There are major economic and energy opportunities for the United States in Kazakhstan. American investment in Kazakhstan’s energy sphere runs in the tens of billions of dollars, and there is potential for more. Additionally, there are trade and investment opportunities. U.S. trade activity with Kazakhstan totaled more than $2.1 billion in 2018.REF

Kazakhstan’s location on the Caspian Sea littoral means it is one of the key energy players in the world. The 1.8 million barrels a day output in 2018 seen in Kazakhstan exceeds the output of seven members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. With the recent completion of maintenance, the Kashagan oilfield is back online, and Kazakh oil production is expected to increase even more.REF Kazakhstan’s energy production could help offset European dependence on Russia. This, in turn, would have an indirect impact on U.S. security interests in Europe, because each barrel of oil and cubic foot of natural gas that Europe gets from Kazakhstan is one fewer that it gets from Russia. Kazakhstan also supplies a fifth of U.S. civilian uranium for power generation.

Another important factor for U.S.–Kazakh relations is Afghanistan. As the region’s biggest economy and a secular republic, Kazakhstan has a direct interest in ensuring that Afghanistan becomes stable.

While Kazakhstan does not share a direct land border with Afghanistan, the region is intertwined with historic trading routes still linking the two countries today. Kazakhstan has played a constructive role in the country. Over the years, it has offered millions of dollars’ worth of assistance and has agreed to trade deals with Kabul worth hundreds of millions of dollars more.

Kazakhstan has used its two-year term as a non-permanent member of the U.N. Security Council to focus on the Afghan situation. For example, this year it organized a visit by Security Council members to Afghanistan.

Kazakhstan recently announced that $50 million will be provided to educate 1,000 Afghan students.REF This is particularly important because evidence shows that Afghans who study in the region are more likely to return home and contribute to rebuilding the country, while those who travel further afield for their education tend to remain overseas.

Turkmenistan: The Reclusive Regime. Located on the eastern shore of the Caspian, Turkmenistan is perhaps the world’s most closed society after North Korea. The last presidential elections were in February 2017, and President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov was re-elected to a third five-year term with 97 percent of the vote.REF International observers regarded these elections as flawed.REF The presidency tightly controls all three branches of government: the economy, social services, and the mass media.

The cocktail of political and economic mismanagement by Turkmenistan’s elites has left the country in a crisis. Currency depreciation, autarkic policies, and limited spending on public services have led to economic stagnation. Lines for basic goods are now commonplace—especially in the regions outside Ashgabat, the capital.REF Even so, billions of dollars have been wasted on frivolous projects with little or no economic value. The dubious plan for a massive man-made lake in the middle of a desolate desert is expected to cost billions.REF Ashgabat holds the record for the highest density of white marble–clad buildings anywhere in the world. According to the entry in The Guinness Book of World Records, “[I]f the marble was laid out flat, there would be one square meter of marble for every 4.87 m² of land.”REF

Those international investors who could enter the country are reluctant to do so, because little has been done to improve the business climate, privatize state-owned industries, or combat rampant corruption. Rigid labor regulations and the nearly complete absence of property rights further limit private-sector activity. Like other countries with economies linked to Russia, Turkmenistan has felt the negative effects of Russia’s poor economic performance and economic sanctions.

The greatest potential for Turkmenistan to turn around its dire economic situation is with its natural gas resources. Berdymukhamedov has encouraged some foreign investment in the energy sector, but not enough to make a meaningful difference.

Turkmenistan holds some of the world’s largest natural gas reserves but has only a few options for exporting these resources to the rest of the world.REF Currently, Turkmenistan’s gas exports rely heavily on China. A pricing dispute stopped exports to Iran, and new U.S. sanctions against Tehran would make things difficult for Ashgabat, even if the pricing dispute were resolved. Russia has resumed importing Turkmen gas in 2019 after stopping imports in 2016.REF The details of how much gas Russia will import are unknown, so it is impossible to see if this will help the economic situation in any significant way.

The agreement last year on the legal status of the Caspian Sea has given a green light to construct the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline that could connect Turkmenistan to European markets. Even so, there is a lack of political will in Ashgabat to get the project off the ground. Other projects that could help diversify Turkmen gas exports, like the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India Pipeline (TAPI) are also many years away from becoming a reality.

In foreign relations, Turkmenistan leans toward isolationism and self-described “permanent neutrality.”REF While Ashgabat has cordial relations with its Caspian neighbors, it has refrained from joining the EEU or the CSTO. Even so, Turkmen relations with Russia have been getting closer over recent years. During a visit by President Putin in October 2017, the two countries signed 14 bilateral documents on issues pertaining to cooperation in “culture, tourism, agriculture, humanitarian spheres and other areas.” In addition, the two leaders signed “a bilateral treaty on strategic partnership”—the details of which remain vague to the public.REF

Moscow is increasingly concerned about the deteriorating security situation in northern Afghanistan and Turkmenistan’s seeming inability to contain the threat. Also exacerbating the dire economic situation is the security situation on the Turkmen–Afghan border.

As Taliban and other Central Asian militants have been pushed away from the Afghanistan–Pakistan border region, many have found their way to northern Afghanistan. Since early 2015, there has been an increasing number of security incidentsREF involving Taliban militants and Turkmen border guards resulting in the deaths of dozens of Turkmen conscripts.REF Most recently, in March 2019, Afghan forces were chased into Turkmenistan by the Taliban.REF In response, the authorities in Turkmenistan have attempted to seal its border with Afghanistan using fences, ditches, and various means of surveillance.

Russian officials have visited Turkmenistan to offer Russian weaponry and training to help Turkmenistan to secure its border. No doubt, Moscow sees the situation as another opportunity to gain another strategic foothold in the region.

Azerbaijan: An Important Piece of the Puzzle

Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, is arguably the most important city on the Caspian Sea. It is home to the Caspian’s largest port and serves as the transportation hub for goods shipped between Europe and Central Asia. When Peter the Great captured Baku in 1723 during a war with Persia, he described the captured city as “the key to all our business” in the region.REF Ever since the first oil well was drilled just outside Baku in 1846, the city has been vital to the region’s oil and gas industry. For Europe, Azerbaijan provides a significant oil and gas alternative to Russia.

Everything the government in Azerbaijan does must be seen through the lens of Armenia’s occupation of Nagorno–Karabakh. The occupied region accounts for almost 20 percent of Azerbaijan’s international territoryREF and is one of the main drivers of foreign and domestic policy in Baku.

The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan started in 1988 when Armenia made territorial claims on Azerbaijan’s Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. By 1992, Armenian forces and Armenian-backed militias occupied almost 20 percent of Azerbaijan, including the Nagorno–Karabakh region and all or part of Agdam, Fizuli, Jebrayil, Kelbajar, Lachin, Qubatli, and Zangelan Provinces.

During 1992 and 1993, the U.N. Security Council adopted four resolutions on the Nagorno–Karabakh war.REF Each resolution confirmed the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan to include Nagorno–Karabakh and the seven surrounding districts, and called for the withdrawal of all occupying Armenian forces from Azerbaijani territory.

A cease-fire agreement was signed in 1994, and the conflict has been described as “frozen” since then. Intense fighting in April 2016 left 200 dead.REF According to the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense, more than eight square miles were liberated by Azerbaijani forces—though this figure is disputed by Armenia, which claims it is far less.REF In early summer 2018, Azerbaijani forces successfully launched an operation to re-take territory around Günnüt, a small village strategically located in the mountainous region of Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.REF Both the 2016 and the 2018 incidents marked the only changes in territory since 1994.

Although the Nagorno–Karabakh region is inland and hundreds of miles from the Caspian, the conflict can still affect the region. Key transportation infrastructure, such as the BTC pipeline and the SCP run within several miles of the front lines, and any major outbreak of warfare would immediately threaten them. (See Textbox 1, “The Ganja Gap.”)

The most likely scenario for the Nagorno–Karabakh conflict is maintaining the status quo. Although there have been some promising overtures by Baku and Yerevan in recent months,REF the Minsk Group,REF which was tasked with bringing a lasting peace to the war, is now defunct due to the breakdown in Western relations with Russia over Ukraine. Russia has gained too much influence in Yerevan and Baku, especially with lucrative defense contracts with both sides, to want to see the conflict resolved anytime soon.

Azerbaijan has been arming heavily. For 2019, its defense and security budget is approximately $2 billion.REF This is almost two-thirds of Armenia’s entire 2019 state budget of $3.1 billion.REF Buoyed by the territorial gains and relative military success in 2016 and 2018, it is not inconceivable that, under certain circumstances, Azerbaijan might use military force to liberate the Nagorno–Karabakh region and the seven surrounding districts.REF

Azerbaijan is an important U.S. partner for a number of reasons. Azerbaijan is a strong supporter of Israel. It was a staunch ally during the Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns, and Baku has contributed greatly to U.S. counterterrorism efforts since 9/11. Azerbaijan is part of NATO’s Partnership for Peace program and participates in NATO training exercises and officer exchanges. Although Azerbaijan is not actively seeking to join NATO, it participates in NATO-led missions and has close relations with other NATO members and partners, including Turkey and Georgia.

Azerbaijan emerged on the world stage as a major energy power during the 1990s. In 1994, it signed the Contract of the Century agreement with BP and 10 other international oil companies to open up the country’s vast resources in the Caspian Sea. Since then, it has become a major hub for energy production and transport.

Although Azerbaijan is a Muslim-majority country, it is a very secular society. Azerbaijan has a thriving Jewish population estimated to be 20,000 strongREF and is home to the largest all-Jewish settlement outside Israel. Azerbaijan provides Israel with 40 percent to 45 percent of its oil.REF Israel also sells weapons to Azerbaijan. As a sign of how close the bilateral relationship is between the two countries, Benjamin Netanyahu visited Azerbaijan in 2016.REF

The U.S.–Azerbaijani relationship faces challenges: It suffers from a lopsided policy pursued by Washington heavily focused on lofty human rights goals, often at the expense of strategic American interests in the region.

Rightly or wrongly, there is a feeling in Baku that Azerbaijan is singled out for sustained criticism by the West—mainly by Europe, but also by the U.S.—in contrast to the almost complete silence that greets the activities of some other countries.

Human rights issues have been a persistent problem in the relationship. In recent years, there have been legitimate concerns about freedom of the press and the slow speed of democratization in Azerbaijan due to a number of high-profile arrests of prominent journalists, bloggers, and political activists.REF These are worrying developments for U.S.–Azerbaijani relations.

While Washington should continue to press for improvements on human rights, U.S. policymakers cannot allow that issue to create a lopsided foreign policy that undercuts the United States’ broader interests in the region.

The state of human rights in Azerbaijan should not be the sole driver of U.S. engagement with Baku. U.S. engagement with Azerbaijan needs to take a multifaceted approach that involves energy, security, human rights, and geopolitical concerns. While some of Baku’s recent actions against certain elements of the media and other international organizations are concerning, these incidents should not trump other aspects of U.S.–Azerbaijani relations.

Another major obstacle to better U.S. and Azerbaijani relations occurred in 1992 when Congress passed Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act as a result of the influential Armenian lobby. In sum, Section 907 prevents the U.S. from providing military aid to Azerbaijan and identifies Azerbaijan as the aggressor in its war with Armenia. This latter point is curious considering that Armenia is the aggressor and Azerbaijan is the victim in the Nagorno–Karabakh conflict.

After 9/11, the Bush Administration recognized the important role that Azerbaijan would play in the campaign in Afghanistan (and later Iraq) and annually waived Article 907. Both the Obama and Trump Administrations continued waiving Section 907.REF Azerbaijan is the only former Soviet Republic that has restrictions, such as Section 907, placed on it. Even the most casual observer can see that the origins of Section 907 were politically motivated by certain lobby groups in the U.S. and not connected to larger U.S. strategy or goals in the region.

Azerbaijan will continue to be a regional economic leader in the South Caucasus and an important economic actor in the Caspian region. If correct policies are pursued, Azerbaijan will serve as an important alternative source of energy for Europe well into the future.

Azerbaijan will continue to look to the West. But it also realizes that while the U.S. might come and go in the region, Iran and Russia are there to stay. This is why Europe and the U.S. need to stay engaged with Azerbaijan and encourage Azerbaijan to maintain good relations with its neighbors, but also to stay focused on deeper cooperation with the West.

Energy and Caspian Ownership

The Caspian region has an estimated 48 billion barrels of oil and 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in proved and probable reserves.REF In terms of total global proved and probable reserves, this is a relatively small amount. However, every drop of oil and gas that Europe can buy from Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, or Turkmenistan is one fewer that it must depend on from Russia. Also, as technology advances, the available oil and gas resources in the region will only increase.

The Caspian countries’ ability to increase their energy exports depends on five factors:

- The possible increase in domestic energy consumption. Obviously, if domestic demand outpaces production, the Caspian region can export less oil and gas.

- The price of oil. The sharp drop in the cost of crude in 2014 had a big impact on the global energy industry. During this time in one 12-month period, the oil and gas sector lost an estimated 70,000 jobs and cancelled $200 billion in spending on new projects worldwide.REF The Caspian region, where production costs are already high for geographical and political reasons, is not immune to such effects.

- The rate at which additional export infrastructure can be built and made operational. The Caspian’s geographical isolation relative to the outside world makes transporting oil and gas out of the region into the global market a challenge. Building key pipeline, rail, and other transit projects requires substantial investment. When energy prices are low, this situation is exacerbated.

- The degree to which regional cooperation deepens. The history of the region, coupled with religious and cultural differences, fosters distrust amongst many of the Caspian countries and with outside countries wanting to do business in the region.

- The region’s stability and security. Stability is required to encourage foreign investment in the region. Foreign investment is needed to build the infrastructure required to export oil and gas. The same applies for oil and gas exploration and extraction.

Overarching the region’s economic, security, and energy challenges is the issue of Caspian ownership. During the reign of the Soviet Union, ownership of the Caspian was divided between Russia and Persia (later Iran). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan emerged as sovereign and independent states without an agreement on how to divide or share the Caspian Sea among the five littoral countries.

After 22 years, 52 working group meetings, and five Caspian Summits, the leaders of the five Caspian nations signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea during a meeting in Aktau, Kazakhstan, in August 2018. This agreement is notable for a number of reasons:

- The debate over Caspian ownership has traditionally focused on the body of water’s status as either a sea or a lake—both would mean certain things in terms of delineation and use.REF However, instead of choosing either “sea” or “lake,” the agreement gave the Caspian a “Special Legal Status.”

- The issue of delineating the Caspian’s maritime borders, including its seabed, was not included in the agreement, other than repeating what was already agreed upon in 2014—that each Caspian country’s sovereignty extends 15 nautical miles from shore for mineral exploration and an additional 10 nautical miles for fishing rights.REF The remainder is for joint use. Instead, the leaders agreed in Aktau that any delineation of maritime borders will be done on a bilateral basis amongst the countries concerned.

- Another important aspect of the agreement is allowing the construction of undersea pipelines. This is probably the most noteworthy aspect of the agreement. In the past, Iran and Russia argued that any pipeline must first have the agreement of all five littoral states. However, the deal allows pipelines to be established with only the consent of the countries involved in the project. This could finally give the green light for a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline connecting Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan. This would have major ramifications for the Southern Gas Corridor and Europe’s energy security.

- Non-Caspian countries are now barred from having a military presence on the Caspian. Although no outside power is seriously considering a naval presence on the Caspian—which, other than a few canals passing through Russia, is landlocked—this agreement is important for domestic audiences. This is especially true in Iran and Russia, both of which play up the threat of U.S. or NATO involvement in the region.REF

In particular, ownership of the seabed remains a highly contentious issue. Currently, most of the proved oil and gas is located close to the coastline and is easily extracted. This makes the ownership of the Caspian Sea less of an issue right now than it will be in the future. However, as new technology becomes affordable and available, new fields will be exploited further away from the shore. This is why an agreement delineating the waters is so important.

Although there was much optimism associated with the 2018 Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, there is still a lack of political will to go further and delineate the waters, and this issue will continue to be the source of many regional problems.

A Transport Hub of Eurasia

In 1906, the region’s first oil pipeline was completed, connecting Baku on the Caspian Sea with Batumi on the Black Sea. More than 100 years later, this pipeline, measuring a mere eight inches in diameter, has been replaced with a modern network of natural gas and oil pipelines connecting the heart of Asia with Europe. With proper investment and the correct policies, oil, gas, and other goods will be flowing in all directions from the Caspian region.

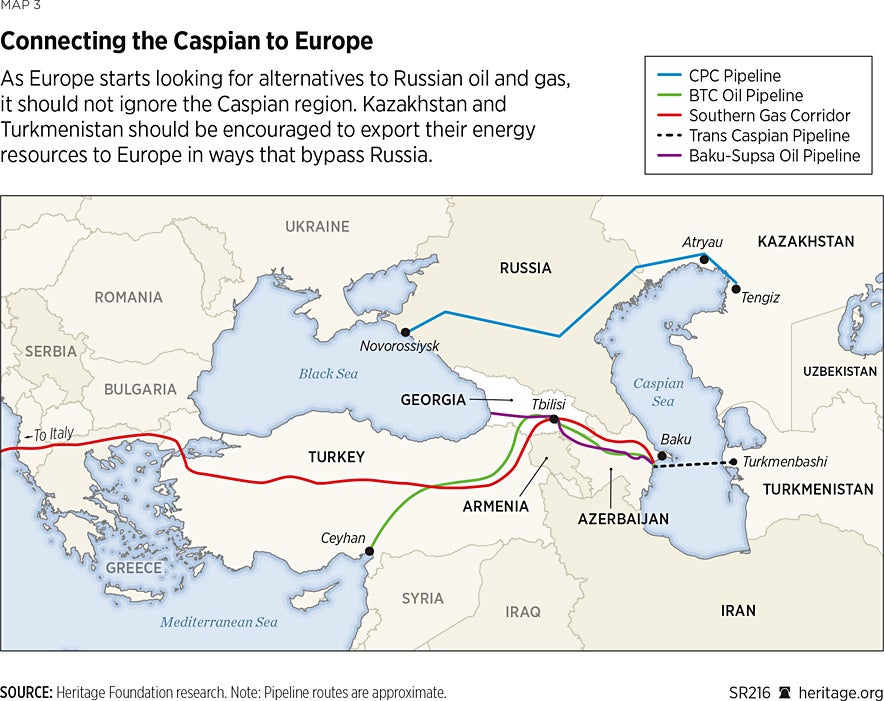

There has been much progress since 1906 connecting the Caspian to the outside world. The Baku–Supsa pipeline, finished in 1999, brings oil from Azerbaijan to Georgia’s Black Sea coast. The BTC pipeline, operational in 2006 and strongly backed politically by the U.S. during the Clinton Administration, brings oil from the Caspian region to the outside world through Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. The SCP went into service in 2006 and connects Azerbaijan’s gas fields to Turkey via Georgia. Russia’s Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) pipeline, opened in 2001, brings oil, mainly from Kazakhstan, to global markets by transporting it to Russia’s Black Sea port of Novorossiysk.

More recently, in June 2018, construction finished on the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline, further linking Azerbaijan to Turkey. This will then link with the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, which will run from the Turkish–Greek border to Italy via Albania and the Adriatic Sea when it is completed in 2020.REF

These new gas pipelines, in addition to the existing SCP, are known as the Southern Gas Corridor. Once fully operational, the Southern Gas Corridor will be a network of pipelines running 2,100 miles across seven countries, suppling 60 billion cubic meters of natural gas to Europe.REF

There are also a number of other projects in the works. The Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline project, commonly referred to as the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) Pipeline, could fundamentally change the natural gas connectivity of Central Asia.REF This proposed 1,100-mile pipeline could carry natural gas from Turkmenistan to India to help block Russian and Chinese hegemony over the region’s energy market. Construction on the TAPI Pipeline has been delayed by more than a decade for security concerns, particularly in Afghanistan, and because of legal issues in Turkmenistan.

The security situation in Afghanistan remains problematic, although local Taliban officials have stated they would not attack the pipeline if built.REF Apparently, the legal roadblock in Turkmenistan has also been resolved and construction has started, but because of the limited (and often conflicted) nature of information coming out of Turkmenistan, it is anyone’s guess as to what the status is.REF

It is strategically important for Europe to access as much oil and gas from the region as possible. Europe already imports oil and gas from the Caspian, primarily from Azerbaijan, but it desperately needs oil and gas from Central Asia, too. To this end, the U.S. and Europe need to support oil and gas transportation initiatives that connect the eastern shore of the Caspian with the western shore while bypassing both Russia and Iran.

Until recently, this has not been a major problem with oil, but the situation changed in early 2019 when Turkmenistan unexpectedly stopped transporting oil to AzerbaijanREF (for further transport in the global market via the BTC pipeline) and decided to send its oil to the Russian port of Makhachkala (and then on to Russia’s Black Sea port of Novorossiysk to access the global market). Ashgabat’s motives are unclear, but there is reason to suspect this switch from Baku to Makhachkala was part of a larger deal with Moscow, with Russia purchasing Turkmen gas for the first time since 2016.

The Swiss company Vitol was contracted to deliver the oil to Makhachkala, but has since had problems finding enough oil tankers in the Caspian to fulfill the requirement.REF Reportedly, Vitol has been leasing Russian ships on the U.S. sanctions list. (They have been used in the delivery of oil to occupied Crimea and Syria.)REF As a consequence of Vitol’s inability to transport Turkmen oil at the capacity needed, oil production in Turkmenistan is expected to decrease, further affecting the already struggling economy there.REF

Kazakhstan has been transporting its oil to Europe via Russia’s Black Sea port of Novorossiysk through the CPC pipeline. However, since Kazakhstan’s Kashagan field is increasing production, it is likely that the CPC pipeline alone will not be able to handle this extra volume.REF Since the BTC pipeline currently has spare capacity, and because it bypasses Russia, this option makes sense for Kazakhstan and should be encouraged by the U.S.

In addition to pipelines, new ports are being built, and new rail networks are being upgraded and extended.

Azerbaijan’s new Port of Baku at Alat, about 60 miles south of the capital, is only partially operational. Once fully operational and complete, this port will greatly expand regional trade. Rail lines form the main basis of the International North–South Transport Corridor, which is expected to reduce transit costs between Russia in the north and India in the south and everything in between. The Caspian countries are an important part of the International North–South Transport Corridor project.

The Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway, the modern-day successor to the Transcaucasian Railway, opened in September 2017. Its starting point is at the new Port of Baku at Alat. In the long term, it is expected to move 15 million tons of freight and 3 million passengers each year.REF

A Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline

A pipeline is the only economically viable way to move natural gas across the Caspian Sea. This means that right now there is no profitable way to get Central Asia’s gas to Europe without first going through Russia.

The idea of constructing a natural gas pipeline across the Caspian has been debated for decades. However, there are three reasons why regional countries, Europe, and the U.S. should push for a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline now:

- Progress is being made with new pipeline projects in the region that would benefit from Turkmen gas. Azerbaijan started delivering gas to Turkey in mid-2018 via the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP),REF and is poised to send gas to Italy via the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) by next year.REF Also next year, the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) is expected to start delivering gas from Azerbaijan all the way to Europe.REF With an expandable capacity of 31 billion cubic meters (bcm),REF TANAP and the SGC will be able to deliver gas from any future Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline.

- Europe, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan all need a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline, albeit for different reasons. Europe is actively seeking alternatives to Russian energy resources. Azerbaijan is trying to cement its position as the region’s most important energy player. Turkmenistan faces a severe economic crisisREF and needs to find new markets for its natural gas.

- The Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea was finally agreed in 2018, paving the way for a potential pipeline. Signed by all five Caspian littoral countries, this allows pipelines to be established with the consent of only the countries involved in the project.REF This is a major change for the better. In the past, Iran and Russia argued that any pipeline must first have the agreement of all five littoral states. The new agreement could finally give the green light for a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline once the two interested parties, in this case Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, come to an agreement.

While the ultimate goal would be a full-fledged pipeline delivering natural gas from the eastern shore of the Caspian to the Western shore, Baku and Ashgabat ought to be more modest with their ambition at first.

For the Turkmens in particular, lowering the level of ambition would be difficult. Ashgabat has already constructed the so-called East-West pipeline, a 483-mile natural gas pipeline connecting the country’s Mary province in the east with Turkmenistan’s Caspian coast.REF The East-West Pipeline has the potential to transport 30 bcm annually.REF Understandably, Turkmen authorities want any future Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline to match this capacity, but this is an unrealistic goal in the beginning.

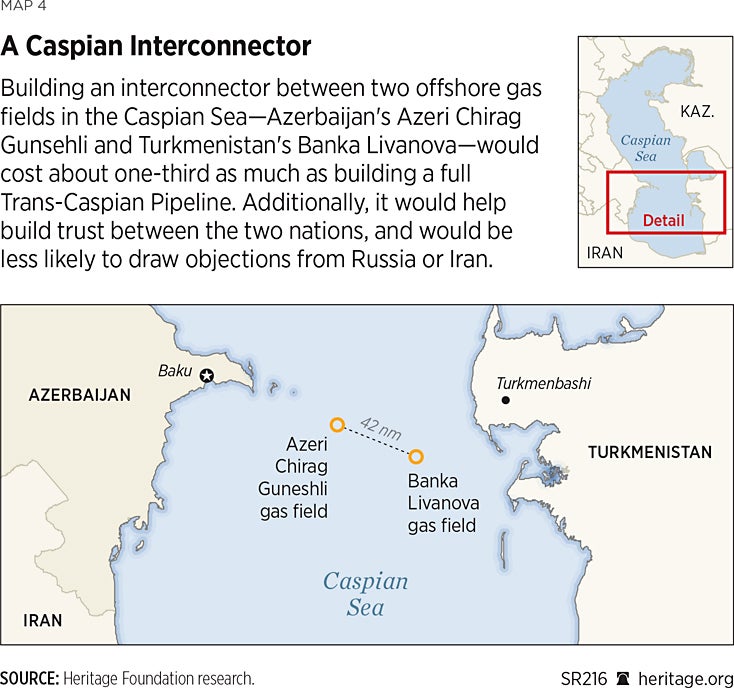

Instead of constructing a pipeline first, Baku and Ashgabat should focus on constructing an interconnector between Azerbaijan’s offshore Azeri Chirag Guneshli gas field and Turkmenistan’s Banka Livanova offshore gas field. Over time, options should be explored to include Kazakh gas fields using interconnectors, since some Kazakh fields are in close enough proximity to be commercially viable.

This modest approach early on would accomplish three things:

- It would be a proof of concept. It would be a tangible, quick, and affordable way to demonstrate that the eastern side of the Caspian can be connected to the western side of the Caspian by a pipeline to deliver natural gas. Building an interconnector linking Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan’s existing gas fields would need to be only approximately 60 miles long, and could be constructed for only $500 million—compared to an estimated $1.5 billion for a full Trans-Caspian pipeline.REF An interconnector would be a significant step forward contributing to the long-term energy security of Europe.

- It would help to build confidence and trust between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. These two countries do not have an agreement on their maritime borders in the Caspian, and there has been tension and confrontation between the two in the past.REF For the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline to become successful, both countries will have to trust one another—and eventually agree to a maritime border.

- It would likely be more politically acceptable to Iran and Russia than a full-blown pipeline. Although the Caspian agreement states that a pipeline can be built as long as the countries involved in the project give consent, it is likely that Russia and Iran would find other ways to delay or even prevent the project from happening.REF However, considering that current geopolitical circumstances are leaving both Russia and Iran heavily engaged elsewhere around the world, it is very possible that an interconnector would be below the threshold that would otherwise ring alarm bells in Moscow and Tehran.

Completing the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline promises several benefits, even for the United States. The most obvious benefit of a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline is that it would improve Europe’s energy security by giving it another alternative to Iranian and Russian gas. Greater European energy security will lead to more stability. This, in turn, could indirectly affect U.S. treaty obligations under NATO.

The pipeline would also improve regional stability by calming Azerbaijani–Turkmen relations, which have been strained in the Caspian over the past few years. From Ashgabat’s perspective, the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline would also help to diversify its energy export market, which is dependent on China and Russia.

The Trump Administration is recognizing this. In a recent letter offering America’s wishes for Nowruz, the Persian New Year, President Trump reportedly wrote to his Turkmen counterpart, President Berdymukhamedov: “I hope that Turkmenistan will be able to seize new opportunities for exporting gas to the West following the recent determination of the legal status of the Caspian Sea.”REF

What the U.S. Should Do

The Caspian Sea is an important, if often overlooked, region in regard to many of the challenges that the U.S. faces around the world, such as a resurgent Russia, an emboldened Iran, wavering allies, a growing China, and the rise of Islamic extremism.

America can take a number of steps to safeguard its political, economic, and security interests in the region. The United States should:

- Plan a presidential visit to Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. No sitting U.S. President has visited Azerbaijan or Kazakhstan. It is time for this to change. President Trump should visit both. Throughout his time as Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin has visited Kazakhstan 25 times and Azerbaijan six times. A visit by President Trump would send a strong message of the importance of the region to the United States.

- Show a more visible U.S. presence in the region. Although National Security Advisor John Bolton visited Baku in 2018, the most recent Cabinet-level visit in the Caspian region was Hillary Clinton’s South Caucasus tour in 2012. A good way to start re-engagement easily and symbolically would be with a few high-level visits by U.S. officials. The U.S. should send Cabinet-level visitors to build relations in the region.

- Appoint a Special Envoy for Eurasian Energy with a specific focus on the Caspian region. U.S. policymaking in the Caspian region is often a victim of administrative and bureaucratic divisions in the U.S. government. For example, responsibility for the Caspian region is divided amongst three different bureaus in the State Department, two different Combatant Commands in the Department of Defense, and three different directorates in the National Security Council. Not only would the appointment of a Special Envoy send a strong political message to the region, it would also help lead to a coherent cross government policy for the region.

- Offer political support for the construction of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline and the Southern Gas Corridor project. As Europe seeks alternatives to Russian gas, the Southern Gas Corridor and completion of a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline will play important roles. Furthermore, the construction of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline will help to ease regional tensions between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

- Encourage regional countries whenever possible to use pipelines and infrastructure that bypass Russia to get oil and gas to global markets. The BTC pipeline and the soon-to-be operational Southern Gas Corridor both have capacity that needs to be filled. Instead of using Russian pipelines to get oil and gas to global markets, the U.S. should strongly encourage Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to seek non-Russian options. In addition to not relying on Russia to transport energy, using the BTC pipeline and the Southern Gas Corridor offers more opportunities to integrate regional energy transportation. Also, since America has been politically supportive of both pipelines over the years, it only makes sense that the U.S. would want to see them both in use.

- Push back against Nord Stream II. The Nord Stream II pipeline project that would connect Germany with Russia is neither economically necessary, nor geopolitically prudent. It is a political project to greatly increase European dependence on Russian gas, magnify Russia’s ability to use its European energy dominance as a political trump card, and specifically undermine U.S. allies in Eastern and Central Europe. U.S. opposition to Nord Stream II will give political cover to other European countries that have the same concerns but are unwilling to speak out publicly against Germany.