Executive Summary

Unlawful immigration and amnesty for current unlawful immigrants can pose large fiscal costs for U.S. taxpayers. Government provides four types of benefits and services that are relevant to this issue:

- Direct benefits. These include Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation.

- Means-tested welfare benefits. There are over 80 of these programs which, at a cost of nearly $900 billion per year, provide cash, food, housing, medical, and other services to roughly 100 million low-income Americans. Major programs include Medicaid, food stamps, the refundable Earned Income Tax Credit, public housing, Supplemental Security Income, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

- Public education. At a cost of $12,300 per pupil per year, these services are largely free or heavily subsidized for low-income parents.

- Population-based services. Police, fire, highways, parks, and similar services, as the National Academy of Sciences determined in its study of the fiscal costs of immigration, generally have to expand as new immigrants enter a community; someone has to bear the cost of that expansion.

The cost of these governmental services is far larger than many people imagine. For example, in 2010, the average U.S. household received $31,584 in government benefits and services in these four categories.

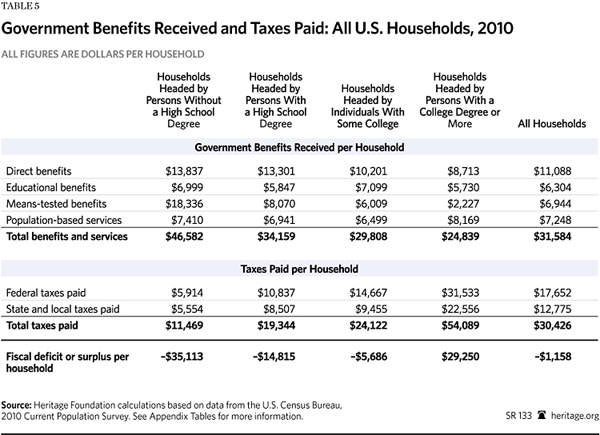

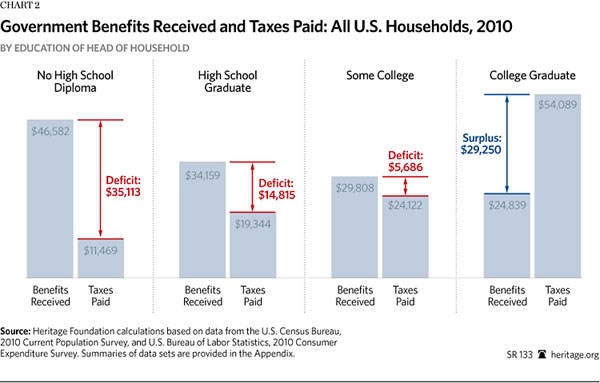

The governmental system is highly redistributive. Well-educated households tend to be net tax contributors: The taxes they pay exceed the direct and means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services they receive. For example, in 2010, in the whole U.S. population, households with college-educated heads, on average, received $24,839 in government benefits while paying $54,089 in taxes. The average college-educated household thus generated a fiscal surplus of $29,250 that government used to finance benefits for other households.

Other households are net tax consumers: The benefits they receive exceed the taxes they pay. These households generate a “fiscal deficit” that must be financed by taxes from other households or by government borrowing. For example, in 2010, in the U.S. population as a whole, households headed by persons without a high school degree, on average, received $46,582 in government benefits while paying only $11,469 in taxes. This generated an average fiscal deficit (benefits received minus taxes paid) of $35,113.

The high deficits of poorly educated households are important in the amnesty debate because the typical unlawful immigrant has only a 10th-grade education. Half of unlawful immigrant households are headed by an individual with less than a high school degree, and another 25 percent of household heads have only a high school degree.

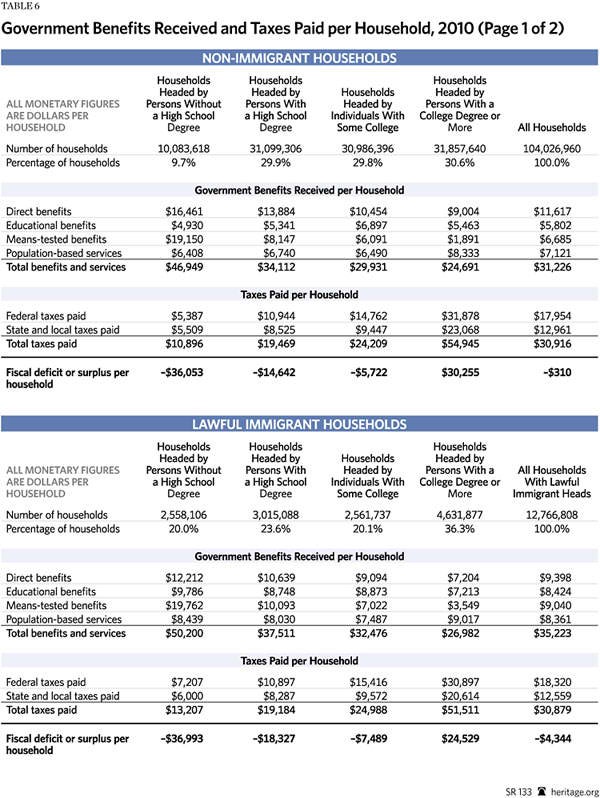

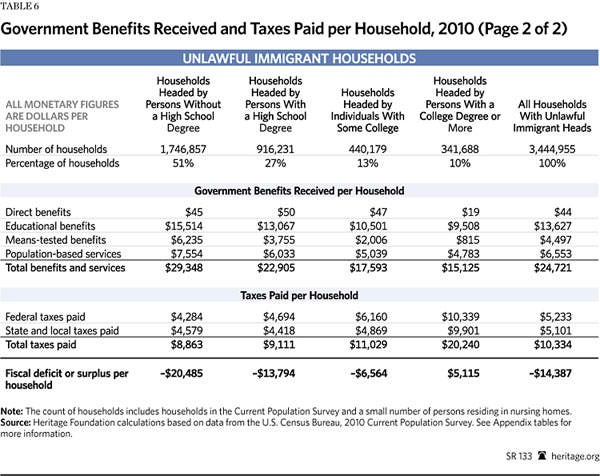

Some argue that the deficit figures for poorly educated households in the general population are not relevant for immigrants. Many believe, for example, that lawful immigrants use little welfare. In reality, lawful immigrant households receive significantly more welfare, on average, than U.S.-born households. Overall, the fiscal deficits or surpluses for lawful immigrant households are the same as or higher than those for U.S.-born households with the same education level. Poorly educated households, whether immigrant or U.S.-born, receive far more in government benefits than they pay in taxes.

In contrast to lawful immigrants, unlawful immigrants at present do not have access to means-tested welfare, Social Security, or Medicare. This does not mean, however, that they do not receive government benefits and services. Children in unlawful immigrant households receive heavily subsidized public education. Many unlawful immigrants have U.S.-born children; these children are currently eligible for the full range of government welfare and medical benefits. And, of course, when unlawful immigrants live in a community, they use roads, parks, sewers, police, and fire protection; these services must expand to cover the added population or there will be “congestion” effects that lead to a decline in service quality.

In 2010, the average unlawful immigrant household received around $24,721 in government benefits and services while paying some $10,334 in taxes. This generated an average annual fiscal deficit (benefits received minus taxes paid) of around $14,387 per household. This cost had to be borne by U.S. taxpayers. Amnesty would provide unlawful households with access to over 80 means-tested welfare programs, Obamacare, Social Security, and Medicare. The fiscal deficit for each household would soar.

If enacted, amnesty would be implemented in phases. During the first or interim phase (which is likely to last 13 years), unlawful immigrants would be given lawful status but would be denied access to means-tested welfare and Obamacare. Most analysts assume that roughly half of unlawful immigrants work “off the books” and therefore do not pay income or FICA taxes. During the interim phase, these “off the books” workers would have a strong incentive to move to “on the books” employment. In addition, their wages would likely go up as they sought jobs in a more open environment. As a result, during the interim period, tax payments would rise and the average fiscal deficit among former unlawful immigrant households would fall.

After 13 years, unlawful immigrants would become eligible for means-tested welfare and Obamacare. At that point or shortly thereafter, former unlawful immigrant households would likely begin to receive government benefits at the same rate as lawful immigrant households of the same education level. As a result, government spending and fiscal deficits would increase dramatically.

The final phase of amnesty is retirement. Unlawful immigrants are not currently eligible for Social Security and Medicare, but under amnesty they would become so. The cost of this change would be very large indeed.

- As noted, at the current time (before amnesty), the average unlawful immigrant household has a net deficit (benefits received minus taxes paid) of $14,387 per household.

- During the interim phase immediately after amnesty, tax payments would increase more than government benefits, and the average fiscal deficit for former unlawful immigrant households would fall to $11,455.

- At the end of the interim period, unlawful immigrants would become eligible for means-tested welfare and medical subsidies under Obamacare. Average benefits would rise to $43,900 per household; tax payments would remain around $16,000; the average fiscal deficit (benefits minus taxes) would be about $28,000 per household.

- Amnesty would also raise retirement costs by making unlawful immigrants eligible for Social Security and Medicare, resulting in a net fiscal deficit of around $22,700 per retired amnesty recipient per year.

In terms of public policy and government deficits, an important figure is the aggregate annual deficit for all unlawful immigrant households. This equals the total benefits and services received by all unlawful immigrant households minus the total taxes paid by those households.

- Under current law, all unlawful immigrant households together have an aggregate annual deficit of around $54.5 billion.

- In the interim phase (roughly the first 13 years after amnesty), the aggregate annual deficit would fall to $43.4 billion.

- At the end of the interim phase, former unlawful immigrant households would become fully eligible for means-tested welfare and health care benefits under the Affordable Care Act. The aggregate annual deficit would soar to around $106 billion.

- In the retirement phase, the annual aggregate deficit would be around $160 billion. It would slowly decline as former unlawful immigrants gradually expire.

These costs would have to be borne by already overburdened U.S. taxpayers. (All figures are in 2010 dollars.)

The typical unlawful immigrant is 34 years old. After amnesty, this individual will receive government benefits, on average, for 50 years. Restricting access to benefits for the first 13 years after amnesty therefore has only a marginal impact on long-term costs.

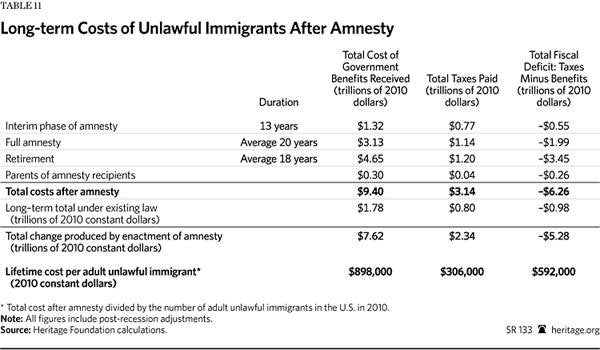

If amnesty is enacted, the average adult unlawful immigrant would receive $592,000 more in government benefits over the course of his remaining lifetime than he would pay in taxes.

Over a lifetime, the former unlawful immigrants together would receive $9.4 trillion in government benefits and services and pay $3.1 trillion in taxes. They would generate a lifetime fiscal deficit (total benefits minus total taxes) of $6.3 trillion. (All figures are in constant 2010 dollars.) This should be considered a minimum estimate. It probably understates real future costs because it undercounts the number of unlawful immigrants and dependents who will actually receive amnesty and underestimates significantly the future growth in welfare and medical benefits.

The debate about the fiscal consequences of unlawful and low-skill immigration is hampered by a number of misconceptions. Few lawmakers really understand the current size of government and the scope of redistribution. The fact that the average household gets $31,600 in government benefits each year is a shock. The fact that a household headed by an individual with less than a high school degree gets $46,600 is a bigger one.

Many conservatives believe that if an individual has a job and works hard, he will inevitably be a net tax contributor (paying more in taxes than he takes in benefits). In our society, this has not been true for a very long time. Similarly, many believe that unlawful immigrants work more than other groups. This is also not true. The employment rate for non-elderly adult unlawful immigrants is about the same as it is for the general population.

Many policymakers also believe that because unlawful immigrants are comparatively young, they will help relieve the fiscal strains of an aging society. Regrettably, this is not true. At every stage of the life cycle, unlawful immigrants, on average, generate fiscal deficits (benefits exceed taxes). Unlawful immigrants, on average, are always tax consumers; they never once generate a “fiscal surplus” that can be used to pay for government benefits elsewhere in society. This situation obviously will get much worse after amnesty.

Many policymakers believe that after amnesty, unlawful immigrants will help make Social Security solvent. It is true that unlawful immigrants currently pay FICA taxes and would pay more after amnesty, but with average earnings of $24,800 per year, the typical unlawful immigrant will pay only about $3,700 per year in FICA taxes. After retirement, that individual is likely to draw more than $3.00 in Social Security and Medicare (adjusted for inflation) for every dollar in FICA taxes he has paid.

Moreover, taxes and benefits must be viewed holistically. It is a mistake to look at the Social Security trust fund in isolation. If an individual pays $3,700 per year into the Social Security trust fund but simultaneously draws a net $25,000 per year (benefits minus taxes) out of general government revenue, the solvency of government has not improved.

Following amnesty, the fiscal costs of former unlawful immigrant households will be roughly the same as those of lawful immigrant and non-immigrant households with the same level of education. Because U.S. government policy is highly redistributive, those costs are very large. Those who claim that amnesty will not create a large fiscal burden are simply in a state of denial concerning the underlying redistributional nature of government policy in the 21st century.

Finally, some argue that it does not matter whether unlawful immigrants create a fiscal deficit of $6.3 trillion because their children will make up for these costs. This is not true. Even if all the children of unlawful immigrants graduated from college, they would be hard-pressed to pay back $6.3 trillion in costs over their lifetimes.

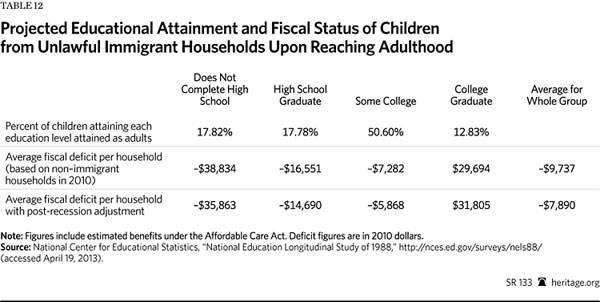

Of course, not all the children of unlawful immigrants will graduate from college. Data on intergenerational social mobility show that, although the children of unlawful immigrants will have substantially better educational outcomes than their parents, these achievements will have limits. Only 13 percent are likely to graduate from college, for example. Because of this, the children, on average, are not likely to become net tax contributors. The children of unlawful immigrants are likely to remain a net fiscal burden on U.S. taxpayers, although a far smaller burden than their parents.

A final problem is that unlawful immigration appears to depress the wages of low-skill U.S.-born and lawful immigrant workers by 10 percent, or $2,300, per year. Unlawful immigration also probably drives many of our most vulnerable U.S.-born workers out of the labor force entirely. Unlawful immigration thus makes it harder for the least advantaged U.S. citizens to share in the American dream. This is wrong; public policy should support the interests of those who have a right to be here, not those who have broken our laws.

Introduction

Each year, families and individuals pay taxes to the government and receive back a wide variety of services and benefits. A fiscal deficit occurs when the benefits and services received by one group exceed the taxes paid. When such a deficit occurs, other groups must pay for the services and benefits of the group in deficit. Each year, therefore, government is involved in a large-scale economic transfer of resources between different social groups.

Fiscal distribution analysis measures the distribution of total government benefits and taxes in society. It provides an assessment of the magnitude of government transfers between groups.

This paper provides a fiscal distribution analysis of households headed by unlawful immigrants: individuals who reside in the U.S. in violation of federal law. The paper measures the total government benefits and services received by unlawful immigrant households and the total taxes paid. The difference between benefits received and taxes paid represents the total resources transferred by government on behalf of unlawful immigrants from the rest of society.

Identifying the Unlawful Immigrant Population

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimates that there were 11.5 million undocumented, or unlawful, foreign-born persons in the U.S. in January 2011.[1] These estimates are based on the fact that the number of foreign-born persons appearing in U.S. Census surveys is considerably greater than the actual number of foreign-born persons who are permitted to reside lawfully in the U.S. according to immigration records.

For example, in January 2011, some 31.95 million foreign-born persons (who arrived in the country after 1980) appeared in the annual Census survey, but the corresponding number of lawful foreign-born residents in that year (according to government administrative records) was only 21.6 million.[2] DHS estimates that the difference—some 10.35 million foreign-born persons appearing in the Census American Community Survey (ACS)—was comprised of unauthorized or unlawful residents. DHS further estimates that an additional 1.15 million unlawful immigrants resided in the U.S. but did not appear in the Census survey, for a total of 11.5 million unlawful residents.[3]

DHS employs a “residual” method to determine the characteristics of the unlawful immigrant population. First, immigration records are used to determine the gender, age, country of origin, and time of entry of all foreign-born lawful residents. Foreign-born persons with these characteristics are subtracted from the total foreign-born population in Census records; the leftover, or “residual,” foreign-born population is assumed to be unlawful. This procedure enables DHS to estimate the age, gender, country of origin, date of entry, and current U.S. state of residence of the unlawful immigrant population in the U.S.

The current Heritage Foundation study uses the DHS reports on the characteristics of unlawful immigrants to identify in the Current Population Survey (CPS) of the U.S. Census a population of foreign-born persons who have a very high probability of being unlawful immigrants.[4] (The Current Population Survey is used in place of the similar American Community Survey because it has more detailed income and benefit information.)

The procedures used to identify unlawful immigrants in the CPS are similar to those used in studies of the unlawful immigrant population produced by the Pew Hispanic Center, the Center for Immigration Studies, and the Migration Policy Institute. Selection procedures included the following:

- The unlawful immigrant population identified in the CPS matched as closely as possible the age, gender, country of origin, year of arrival, and state of residence of the unlawful immigrant population identified by DHS.

- Foreign-born persons who were current or former members of the armed forces of the U.S. or current employees of federal, state, and local governments were assumed to be lawful residents.

- Since it is unlawful for unlawful immigrants to receive government benefits such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and public housing, individuals reporting personal receipt of such benefits were assumed to be lawfully resident.

- Principles of consistency were applied within families; for example, children of lawful residents were assumed to be lawful.

Additional information on the procedures used to identify unlawful immigrants in the CPS is provided in Appendix B. It should also be noted that the Heritage Foundation analysis matched the DHS figures as closely as possible.[5]

The characteristics of the unlawful immigrant population estimated for the present analysis are shown in text Table 1. In 2010, there were 11.5 million unlawful immigrants in the U.S. Some 10.34 million of these appeared in the annual Current Population Survey and were identified by the residual method described above. Following the DHS estimate, an additional 1.15 million unlawful immigrants were assumed to reside in the U.S. but not to appear in Census surveys.

As Table 1 shows, 84 percent of unlawful immigrants came from Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central or South America; 11 percent came from Asia; and 5 percent came from the rest of the world. Unlawful immigrants were almost equally split by gender: 54 percent were males, and 46 percent were females.

Characteristics of Unlawful Immigrants and Unlawful Immigrant Households

Any analysis of the fiscal costs of unlawful immigration must deal with the fact that a great many unlawful immigrants are parents of U.S.-born children. For example, the Pew Hispanic Center estimates that in 2010, there were 5.5 million children residing in the U.S. who have unlawful immigrant parents. Among these children, some 1 million were born abroad and were brought into the U.S. unlawfully; the remaining 4.5 million were born in the U.S. and are treated under law as U.S. citizens. Overall, some 8 percent of the children born in the U.S. each year have unlawful immigrant parents.[6]

The presence of these 4 million native-born children with unlawful immigrant parents is a direct result of unlawful immigration. These children would not reside in the U.S. if their parents had not chosen to enter and remain in the nation unlawfully. Obviously, any analysis of the fiscal cost of unlawful immigration must therefore include the costs associated with these children, because those costs are a direct and inevitable result of the unlawful immigration of the parents. The costs would not exist in the absence of unlawful immigration.

To address that issue, the present study analyzes the fiscal costs of all households headed by unlawful immigrants. (Throughout this study, the terms “households headed by an unlawful immigrant” and “unlawful immigrant households” are used synonymously.)

In 2010, 3.44 million such households appeared in the CPS. These households contained 12.7 million persons including 7.4 million adults and 5.3 million children. Among the children, some 930,000 were unlawful immigrants, and 4.4 million were native-born or lawful immigrants.[7]

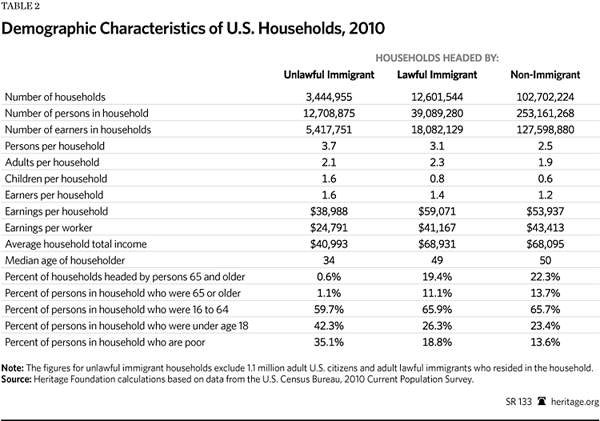

Table 2 shows the characteristics of unlawful immigrant households in comparison to non-immigrant and lawful immigrant households. Unlawful immigrant households are larger than other households, with an average of 3.7 persons per household compared to 2.5 persons in non-immigrant households.[8]

Unlawful immigrant households have more wage earners per household: 1.6 compared to 1.2 among non-immigrant households. However, the average earnings per worker are dramatically lower in unlawful immigrant households: $24,791 per worker compared to $43,413 in non-immigrant households. Contrary to conventional wisdom, non-elderly adult unlawful immigrants are not more likely to work than are similar non-immigrants.

The heads of unlawful immigrant households are younger, with a median age of 34 compared to 50 among non-immigrant householders. Partly because they are younger, unlawful immigrant households have more children, with an average of 1.6 children per household compared to 0.6 among non-immigrant households. The higher number of children tends to raise governmental costs among unlawful immigrant households. (Both lawful and unlawful children in unlawful immigrant households are eligible for public education, and the large number of children who were born in the U.S. are also eligible for means-tested welfare benefits such as food stamps, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program benefits.)

By contrast, there are very few elderly persons in unlawful immigrant households. Only 1.1 percent of persons in those households are over 65 years of age compared to 13.7 percent of persons in non-immigrant households. The absence of elderly persons in unlawful immigrant households significantly reduces current government costs; however, if unlawful immigrants remain in the U.S. permanently, the number who are elderly will obviously increase significantly.

Unlawful immigrant households are far more likely to be poor. Over one-third of unlawful immigrant households have incomes below the federal poverty level compared to 18.8 percent of lawful immigrant households and 13.6 percent of non-immigrant households.

Education Level of Unlawful Immigrant Households

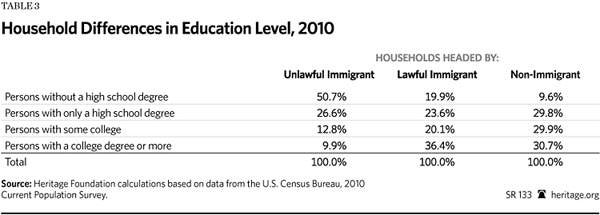

The low wage level of unlawful immigrant workers is a direct result of their low education levels. As Table 3 shows, half of unlawful immigrant households are headed by persons without a high school degree; more than 75 percent are headed by individuals with a high school degree or less. Only 10 percent of unlawful immigrant households are headed by college graduates. By contrast, among non-immigrant households, 9.6 percent are headed by persons without a high school degree, around 40 percent are headed by persons with a high school degree or less, and nearly one-third are headed by college graduates.

The current unlawful immigrant population thus contains a disproportionate share of poorly educated individuals. These individuals will tend to have low wages and pay comparatively little in taxes.

There is a common misconception that the low education levels of recent immigrants are part of a permanent historical pattern and that the U.S. has always admitted immigrants who were poorly educated relative to the native-born population. Historically, this has not been the case. For example, in 1960, recent immigrants were no more likely than non-immigrants to lack a high school degree. By 1998, recent immigrants were almost four times more likely to lack a high school degree than were non-immigrants.[9]

As the relative education level of immigrants fell in recent decades, so did their relative wage levels. In 1960, the average immigrant male in the U.S. actually earned more than the average non-immigrant male. As the relative education levels of subsequent waves of immigrants fell, so did relative wages. By 1998, the average immigrant earned 23 percent less than the average non-immigrant earned.[10]

Aggregate Cost of Government Benefits and Services

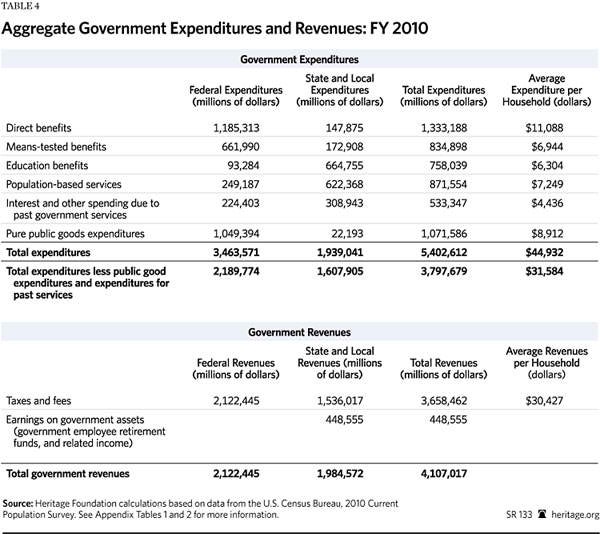

Any analysis of the distribution of benefits and taxes within the U.S. population must begin with an accurate count of the cost of all benefits and services provided by the government. The size and cost of government is far larger than many people imagine. In fiscal year (FY) 2010, the expenditures of the federal government were $3.46 trillion. In the same year, expenditures of state and local governments were $1.94 trillion. The combined value of federal, state, and local expenditures in FY 2010 was $5.4 trillion.[11]

This sum is so large that it is difficult to comprehend. One way to grasp the size of government more readily is to calculate average expenditures per household. In 2010, there were 120.2 million households in the U.S.[12] (This figure includes both multi-person families and single persons living alone.) The average cost of government spending thus amounted to $44,932 per household across the U.S. population.[13]

The $5.4 trillion in government expenditure is not free; it must be paid for by taxing or borrowing economic resources from Americans or by borrowing from abroad. In FY 2010, federal taxes amounted to $2.12 trillion. State and local taxes and related revenues amounted to $1.98 trillion.[14] Together, federal, state, and local taxes amounted to $4.11 trillion. Taxes and related revenues came to 75 percent of the $5.4 trillion in expenditures. The gap between taxes and spending was financed by government borrowing.

Types of Government Expenditure

After the full cost of government benefits and services has been determined, the next step in analyzing the distribution of benefits and taxes is to determine the beneficiaries of specific government programs. Some programs, such as Social Security, neatly parcel out benefits to specific individuals. With programs such as these, it is relatively easy to determine the identity of the beneficiary and the cost of the benefit provided. On the other hand, other government functions such as highway construction do not neatly parcel out benefits to individuals. Determining the proper allocation of the benefits of that type of program is more complex.

To determine the distribution of government benefits and services, this study begins by dividing government expenditures into six categories: direct benefits, means-tested benefits, educational services, population-based services, interest and other financial obligations resulting from prior government activity, and pure public goods.

Direct Benefits. Direct benefit programs involve either cash transfers or the purchase of specific services for an individual. Unlike means-tested programs, direct benefit programs are not limited to low-income persons. By far the largest direct benefit programs are Social Security and Medicare. Other substantial direct benefit programs are unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation.

Direct benefit programs involve a fairly transparent transfer of economic resources. The benefits are parceled out discretely to individuals in the population; both the recipient and the cost of the benefit are relatively easy to determine. In the case of Social Security, the cost of the benefit would equal the value of the Social Security check plus the administrative costs involved in delivering the benefit.

Calculating the cost of Medicare services is more complex. Ordinarily, government does not seek to compute the particular medical services received by an individual. Instead, government counts the cost of Medicare for an individual as equal to the average per capita cost of Medicare services. (This number equals the total cost of Medicare services divided by the total number of recipients.[15]) Overall, government spent $1.33 trillion on direct benefits in FY 2010.

Means-Tested Benefits. Means-tested programs are typically termed welfare programs. Unlike direct benefits, means-tested programs are available only to households that fall below specific income thresholds. Means-tested welfare programs provide cash, food, housing, medical care, and social services to poor and low-income persons.

The federal government operates over 80 means-tested aid programs.[16] The largest are Medicaid; the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC); food stamps; Supplemental Security Income (SSI); Section 8 housing; public housing; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); school lunch and breakfast programs; the WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) nutrition program; and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG). Many means-tested programs, such as SSI and the EITC, provide cash to recipients. Others, such as public housing or SSBG, pay for services that are provided to recipients.

The value of Medicaid benefits is usually counted much as the value of Medicare benefits is counted. Government does not attempt to itemize the specific medical services given to an individual; instead, it computes an average per capita cost of services to individuals in different beneficiary categories such as children, elderly persons, and disabled adults. (The average per capita cost for a particular group is determined by dividing the total expenditures on the group by the total number of beneficiaries in the group.) Overall, the U.S. spent $835 billion on means-tested aid in FY 2010.[17]

Public Education. Government provides primary, secondary, post-secondary, and vocational education to individuals. In most cases, the government pays directly for the cost of educational services provided. In other cases, such as the Pell Grant program, the government in effect provides money to an eligible individual who then spends it on educational services.

Education is the single largest component of state and local government spending, absorbing roughly a third of all state and local expenditures. The average cost of public primary and secondary education per pupil is now around $12,300 per year. Overall, federal, state, and local governments spent $758 billion on education in FY 2010.

Population-Based Services. Whereas direct benefits, means-tested benefits, and education services provide discrete benefits and services to particular individuals, population-based programs generally provide services to a whole group or community. Population-based expenditures include police and fire protection, courts, parks, sanitation, and food safety and health inspections. Another important population-based expenditure is transportation, especially roads and highways.

A key feature of population-based expenditures is that such programs generally need to expand as the population of a community expands. (This quality separates them from pure public goods.) For example, as the population of a community increases, the number of police and firefighters will generally need to expand proportionally.

In The New Americans, a study of the fiscal costs of immigration published by the National Academy of Sciences, the National Research Council (NRC) argued that if service remains fixed while the population increases, a program will become “congested,” and the quality of service for users will deteriorate. Thus, the NRC uses the term “congestible goods” to describe population-based services.[18] Highways are an obvious example. In general, the cost of population-based services can be allocated according to an individual’s estimated utilization of the service or at a flat per capita cost across the relevant population.

A subcategory of population-based services is government administrative support functions such as tax collections and legislative activities. Few taxpayers view tax collection as a government benefit; therefore, assigning the cost of this “benefit” appears to be problematic.

The solution to this dilemma is to conceptualize government activities into two categories: primary functions and secondary functions.

- Primary functions provide benefits directly to the public; they include direct and means-tested benefits, education, ordinary population-based services such as police and parks, and public goods.

- By contrast, secondary or support functions do not provide direct benefits to the public but do provide necessary support services that enable the government to perform primary functions. For example, no one can receive food stamp benefits unless the government first collects taxes to fund the program. Secondary functions can thus be considered an inherent part of the “cost of production” of primary functions, and the benefits of secondary support functions can be allocated among the population in proportion to the allocation of benefits from government primary functions.

Government spent $871 billion on population-based services in FY 2010. Of this amount, some $769.6 billion went for ordinary services such as police and parks, and $101.4 billion went for administrative support functions.

Interest and Other Financial Obligations Relating to Past Government Activities. Often, tax revenues are insufficient to pay for the full cost of government benefits and services. In that case, government will borrow money and accumulate debt. In subsequent years, interest payments must be paid to those who lent the government money. Interest payments for the government debt are in fact partial payments for past government benefits and services that were not fully paid for at the time of delivery.

Similarly, government employees deliver services to the public. Part of the cost of the service is paid for immediately through the employee’s salary, but government employees are also compensated by future retirement benefits. To a considerable degree, expenditures of public-sector retirement are therefore present payments in compensation for services delivered in the past. The expenditure category “interest and other financial obligations relating to past government activities” thus includes interest and principal payments on government debt and outlays for government employee retirement. Total government spending on these items equaled $533.3 billion in FY 2010.[19]

While direct benefits, means-tested benefits, public education, and population-based services will grow as more immigrants take up residence in the United States, this is not the case for interest payments on the debt and related costs. These costs were fixed by past government spending and borrowing and are largely unaffected, at least in the intermediate term, by immigrants’ entry into the United States. While an increased inflow of immigrants will lead to an increase in most forms of government spending, it will not cause an increase in interest payments on government debt in the short term.

To assess the fiscal impact of unlawful immigrants, therefore, the present report follows the procedures used by the National Research Council in The New Americans: That is, it ignores the costs of interest on the debt and similar financial obligations when calculating the net tax burden imposed by lawful and unlawful immigrant households.[20]

On the other hand, while unlawful immigrant households do not increase government debt immediately, such households will, on average, increase government debt significantly over the long term. For example, if an unlawful immigrant household generated a net fiscal deficit (benefits received minus taxes paid) of $20,000 per year and roughly 20 percent of that amount was financed each year by government borrowing, then the immigrant household would be responsible for adding roughly $4,000 to government debt each year. After 50 years, the family’s contribution to growth in government debt would be around $200,000. While these potential costs are significant, they are outside the scope of the current paper and are not included in the calculations presented here.

Pure Public Goods. Economic theory distinguishes between “private consumption goods” and pure public goods. Economist Paul Samuelson is credited with first making this distinction. In his seminal 1954 paper “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure,”[21] Samuelson defined a pure public good (or what he called a “collective consumption good”) as a good “which all enjoy in common in the sense that each individual’s consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual’s consumption of that good.” By contrast, a “private consumption good” is a good that “can be parceled out among different individuals.” Its use by one person precludes or diminishes its use by another.

A classic example of a pure public good is a lighthouse: The fact that one ship perceives the warning beacon does not diminish the usefulness of the lighthouse to other ships. Another clear example of a governmental pure public good would be a future cure for cancer produced by government-funded research: The fact that non-taxpayers would benefit from this discovery would neither diminish its benefit nor add extra costs to taxpayers. By contrast, an obvious example of a private consumption good is a hamburger: When one person eats it, it cannot be eaten by others.

Direct benefits, means-tested benefits, and education services are private consumption goods in the sense that the use of a benefit or service by one person precludes or limits the use of that same benefit by another. (Two people cannot cash the same Social Security check.) Population-based services such as parks and highways are often mentioned as “public goods,” but they are not pure public goods in the strict sense described above. In most cases, as the number of persons using a population-based service (such as highways and parks) increases, the service must either expand (at added cost to taxpayers) or become “congested,” in which case its quality will be reduced. Consequently, use of population-based services such as police and fire departments by non-taxpayers does impose significant extra costs on taxpayers.

Government pure public goods are rare; they include scientific research, defense, spending on veterans, international affairs, and some environmental protection activities such as the preservation of endangered species. Each of these functions generally meets the criterion that the benefits received by non-taxpayers do not result in a loss of utility for taxpayers. Government pure public good expenditures on these functions equaled $978 billion in FY 2010. Interest payments on government debt and related costs resulting from public good spending in previous years add an estimated additional cost of $93.5 billion, bringing the total public goods cost in FY 2010 to $1,071.5 billion.

An immigrant’s entry into the country neither increases the size and cost of public goods nor decreases the utility of those goods to taxpayers. In contrast to direct benefits, means-tested benefits, public education, and population-based services, the fact that unlawful and low-skill immigrant households may benefit from public goods that they do not pay for does not add to the net tax burden on other taxpayers.

This report therefore follows the same methods employed by the National Research Council in The New Americans and excludes public goods from the count of benefits received by unlawful immigrant households.[22] (For a further discussion of pure public goods, see Appendix G.)

Summary: Total Expenditures. As Table 4 shows, overall government spending in FY 2010 came to $5.40 trillion. Direct benefits had an average cost of $11,088 per household across the whole population, while means-tested benefits had an average cost of $6,944 per household. Education benefits and population-based services cost $6,304 and $7,249 per household, respectively. Interest payments on government debt and other costs relating to past government activities cost $4,436 per household. Pure public good expenditures comprised 20 percent of all government spending and had an average cost of $8,912 per household.

Excluding spending on public goods, interest on the debt, and related financial obligations, total spending came to $31,584 per household across the entire population.

Taxes and Revenues

Total taxes and revenues for federal, state, and local governments amounted to $4.107 trillion in FY 2010. The federal government received $2.12 trillion in revenue, while state and local governments received $1.98 trillion.

A detailed breakdown of federal, state, and local taxes is provided in Appendix Tables 6 and 7. The biggest revenue generator was the federal income tax, which cost taxpayers $899 billion in 2010, followed by Federal Insurance Contribution Act (FICA) taxes, which raised $812 billion. Property tax was the biggest revenue producer at the state and local levels, generating $442 billion, while general sales taxes gathered $285 billion.

Over 90 percent of the revenues shown in Appendix Tables 6 and 7 are conventional taxes and revenues; the remaining 9 percent ($449 billion) are earnings from government assets, primarily assets held in state and local government employee pension funds. About one-quarter of these revenues were used to fund current retirement benefits; the rest were accumulated for future use.

Unlike general taxes, these earnings are not mandatory transfers from the population to the government, but rather represent an economic return on assets the government owns or controls. Because they do not represent payments made by households to the government, these earnings are not included in the fiscal balance analysis presented in the body of this paper. If they were included, they would alter the fiscal balance of current government retirees; therefore, they are irrelevant to the main topic of this paper: the fiscal balance of unlawful immigrants.

Summary of Estimation Methodology

The accounting framework used in the present analysis is the same framework employed by the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences in The New Americans.[23] Following that framework, the present study:

- Excludes public goods costs such as defense and interest payments on government debt;

- Treats population-based or congestible services as fully private goods and assigns the cost of those services to immigrant households based either on estimated use or on the immigrant share of the population.[24]

- Includes the welfare and educational costs of immigrant and non-immigrant minor children and assigns those costs to the child’s household;

- Assigns the welfare and educational costs of minor U.S.-born children of immigrant parents in the immigrant household; and

- Assigns the cost of means-tested and direct benefits according to the self-reported use of those benefits in the CPS.

Clearly, any study that does not follow this framework may reach very different conclusions. For example, any study that excludes the welfare benefits and educational services received by the minor U.S.-born children of unlawful immigrant parents from the costs assigned to unlawful immigrant households will reach very different conclusions about the fiscal consequences of unlawful immigration.

An important principle in the analysis is that receipt of means-tested benefits and direct benefits was not imputed or assigned to households arbitrarily. Rather, the cost of benefits received was based on the household’s self-report of benefits in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.[25] For example, the cost of the food stamp benefits received is based on the food stamp benefits data provided by the household. If the household stated it did not receive food stamps, then the value of food stamps within the household would be zero.

Data on attendance in public primary and secondary schools were also taken from the CPS; students attending public school were then assigned educational costs equal to the average per-pupil expenditures in their state. Public post-secondary education costs were calculated in a similar manner.

Wherever possible, the cost of population-based services was based on the estimated utilization of the service by unlawful immigrant households. For example, each household’s share of public transportation expenditures was assumed to be proportional to its share of spending on public transportation as reported in the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX). When data on utilization of a service were not available, the household’s share of population-based services was assumed to equal its share of the total U.S. population.

Federal and state income taxes were calculated based on data from the CPS. FICA taxes were also calculated from CPS data; both the employer and employee share of FICA taxes were assumed to fall on workers. Corporate income taxes were assumed to be borne partly by workers and partly by owners; the distribution of these taxes was estimated according to the distribution of earnings and property income in the CPS.

Sales, excise, and property tax payments were based on consumption data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey.[26] For example, if the CEX showed that households headed by persons without a high school degree accounted for 10 percent of all sales of tobacco products in the U.S., those households were assumed to pay 10 percent of all tobacco excise taxes.

Certain specific adjustments were made for unlawful immigrant households. Since 45 percent of unlawful immigrants are believed to work “off the books,” the federal and state income tax and FICA tax payments that Census imputes for each household were reduced by 45 percent among unlawful immigrant households. The values of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Additional Child Tax Credit that Census imputes based on family income were reduced to zero for unlawful immigrant families since they are not eligible for those benefits. Immigrant children enrolled in government medical programs were assumed to have half the actual cost of non-immigrant children.[27] And unlawful immigrant families were assumed to use parks, highways, and libraries less than lawful households with the same income.

Finally, about 9 percent of the persons in unlawful immigrant households are adult lawful immigrants or U.S. citizens. The benefits received and taxes paid by these individuals have been excluded from the analysis. The overall methodology of the study is described in detail in the Appendices.

Distribution of Government Benefits and Taxes in the U.S. Population

Table 5 shows government benefits received and taxes paid by the average household in the whole U.S. population. In FY 2010, the average household received a total of $31,584 in government direct benefits, means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services. The household paid $30,426 in federal, state, and local taxes. Since the benefits received exceeded taxes paid, the average household had a fiscal deficit of $1,158 that had to be financed by government borrowing.

If earnings in government employee retirement funds were included in the analysis, this small average household deficit would be largely erased. Nonetheless, these figures show that the taxes paid by U.S. households overall barely cover the cost of immediate services received (direct benefits, means-tested aid, education, and population-based services).[28] Public goods such as defense and interest on government debt are funded by government borrowing.

However, these average household figures mask great differences between different types of households. Individual households have different fiscal balances. Many households are net tax contributors: The taxes they pay exceed the direct and means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services they receive. These households generate a “fiscal surplus” that government uses to finance benefits and services for other households. By contrast, other households are net tax consumers: The government benefits and services received by these households exceed taxes paid. These households generate a “fiscal deficit” that must be financed by taxes from other households or by government borrowing.

Table 5 shows that a critical factor in determining the fiscal balance of a household is the education of the head of household. Individuals with higher education levels earn more, pay more in taxes, and receive fewer government benefits. Less-educated individuals tend to receive more in government benefits and pay less in taxes.

Chart 2 shows the average fiscal balance for all U.S. households based on the education level of the head of household. At one extreme are households with college-educated heads; on average, these households receive $24,839 in government benefits while paying $54,089 in taxes. The average college-educated household thus generates a fiscal surplus of $29,250 that government uses to finance benefits for other households.

At the other extreme are households headed by persons without a high school degree. On average, these households receive $46,582 in government benefits (direct, means-tested, education, and population-based services) while paying only $11,469 in taxes. This generates an average fiscal deficit (benefits received minus taxes paid) of $35,113.

The large average fiscal deficit of less-educated households has a bearing on the immigration debate because immigrant families (both lawful and unlawful) have, on average, far lower education levels than non-immigrants. For example, as Table 3 shows, half of unlawful immigrant household heads do not have a high school degree, and another 27 percent have only a high school diploma.

Household Fiscal Balances and Immigration

Table 6 shows the fiscal balance for non-immigrant, lawful immigrant, and unlawful immigrant households. Unlawful immigrant households have the largest annual fiscal deficits at $14,387 per household. Lawful immigrant households have an average annual fiscal deficit of $4,344, and non-immigrant households have a deficit of $310, meaning that taxes paid roughly equal benefits received.[29]

Lawful immigrant households have higher fiscal deficits than non-immigrants for two reasons. The first is lower education levels; 20 percent of lawful immigrant households are headed by individuals without a high school diploma, compared to 10 percent among non-immigrant households. The second reason is high levels of welfare use. There is a popular misconception that immigrants use little welfare. The opposite is true. In fact, lawful immigrants receive the highest level of welfare benefits.

At $9,040, lawful immigrants’ annual welfare benefits are a third higher than non-immigrants’ benefits. This seems paradoxical because lawful immigrants are barred from receiving nearly all means-tested welfare during their first five years in the U.S. As Table 6 shows, this temporary ban has virtually no impact on the overall use of welfare because (a) the ban does not apply to children born inside the U.S. and (b) receipt of welfare occurs continually throughout a lifetime and therefore is little affected by a five- or 10-year moratorium on receipt of aid.

The lack of effectiveness of the five-year ban on welfare receipt in controlling total welfare costs has a direct bearing on the debate about amnesty legislation. It is noteworthy that the highest level of welfare use shown in Table 6 is $19,762 per household per year among lawful immigrant households headed by individuals without a high school diploma. This figure is important because similar levels of welfare use can be expected among unlawful immigrant households receiving amnesty.

Another important point is that the level of welfare benefits received by unlawful immigrant households is significant, despite the fact that unlawful immigrants themselves are ineligible for nearly all welfare aid. The welfare benefits received by unlawful immigrant households go to U.S.-born children within these homes. If undocumented adults within these households are given access to means-tested welfare programs, per-household benefits will reach very high levels.

Cost of Government Benefits and Services Received by Unlawful Immigrant Households

As noted, in 2010, some 3.44 million unlawful immigrant households appeared in Census surveys. Appendix Table 8 shows the estimated costs of government benefits and services received by these households in 73 separate expenditure categories. The results are summarized in Chart 3.

Overall, households headed by an unlawful immigrant received an average of $24,721 per household in direct benefits, means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services in FY 2010. Education spending on behalf of these households averaged $13,627, and means-tested aid (going mainly to the U.S.-born children in the family) averaged $4,497. Spending on police, fire, and public safety came to $3,656 per household. Transportation added another $662, and administrative support services cost $958. Direct benefits came to $44. Miscellaneous population-based services added a final $1,277.

Taxes and Revenues Paid by Unlawful Immigrant Households. Appendix Table 9 details the estimated taxes and revenues paid by unlawful immigrant households in 34 categories. The results are summarized in Chart 4.

Total federal, state, and local taxes paid by unlawful immigrant households averaged $10,334 per household in 2010. Federal and state individual income taxes comprised less than a fifth of total taxes paid. Instead, taxes on consumption and employment (FICA) produced nearly half of the tax revenue for unlawful immigrant households. (The analysis assumes that workers pay both the employer and employee share of FICA tax.) Property taxes (shifted to renters) and corporate profit taxes (shifted to workers) also form a significant part of the tax burden.

It is worth noting that FICA and income taxes reported in Chart 4 have been reduced because the analysis assumes that 45 percent of unlawful immigrant earners work off the books. If all unlawful immigrant workers were employed on the books, these tax payments would increase significantly.

Balance of Taxes and Benefits. On average, unlawful immigrant households received $24,721 per household in government benefits and services in FY 2010. This figure includes direct benefits, means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services received by the household but excludes the cost of public goods, interest on the government debt, and other payments for prior government functions. By contrast, unlawful immigrant households on average paid only $10,334 in taxes. Thus, unlawful immigrant households received $2.40 in benefits and services for each dollar paid in taxes.

Many politicians believe that households that maintain steady employment are invariably net tax contributors, paying more in taxes than they receive in government benefits. Chart 5 shows why this is not the case. As Table 2 shows, unlawful immigrant households have high levels of employment, with 1.6 earners per household and average annual earnings of around $39,000 for all workers in the household. But with average government benefits at $24,721, unlawful immigrant households actually receive 63 cents in government benefits for every dollar of earnings.

To achieve fiscal balance, with taxes equal to benefits, the average unlawful immigrant household would have to pay nearly two-thirds of its income in taxes. Given this simple fact, it is obvious that unlawful immigrant households can never pay enough taxes to cover the cost of their current government benefits and services.

Net Annual Fiscal Deficit. The net fiscal deficit of a household equals the cost of benefits and services received minus taxes paid. As Chart 6 shows, when the costs of direct and means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services are counted, the average unlawful immigrant household had a fiscal deficit of $14,387 (government expenditures of $24,721 minus $10,334 in taxes) in 2010.

For the average unlawful immigrant household to become fiscally solvent, with taxes paid equaling immediate benefits received, it would be necessary to increase the household’s tax payments to 240 percent of current levels. Alternatively, unlawful immigrant households could become solvent only if all means-tested welfare and nearly all public education benefits were eliminated.

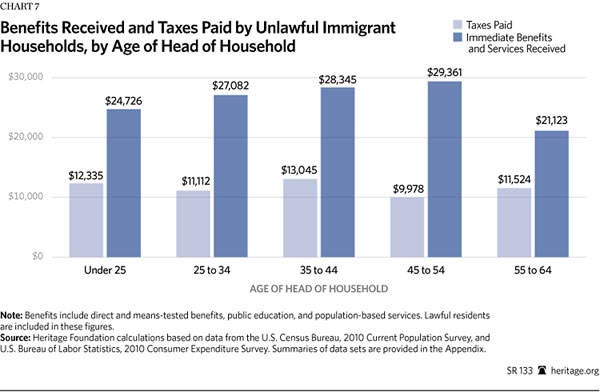

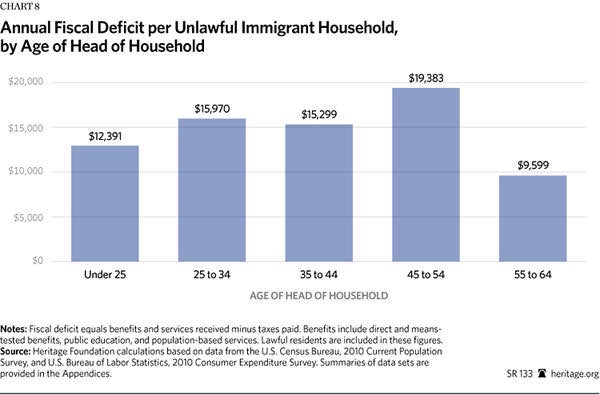

Age Distribution of Benefits and Taxes Among Unlawful Immigrant Households. Many political decision makers believe that because unlawful immigrant workers are comparatively young, they can help to relieve the fiscal strains of an aging society. Charts 7 and 8 show why this is not the case. These charts separate the 3.44 million unlawful immigrant households into five categories based on the age of the head of household.

The benefits levels in Chart 7 again include direct benefits, means-tested benefits, public education, and population-based services. These benefits start at $24,726 for households headed by immigrants under 25 years of age and rise to $28,000 to $29,000 per year as the heads of household reach their 30s and 40s. The increase is driven by a rise in the number of children in each home. As the age of the head of household reaches the late 50s, the number of children in the home falls, and benefits dip to around $21,000 per year. Annual tax payments vary little by the age of the householder, averaging around $12,000 per year in each age bracket.

The critical fact shown in Chart 7 and Chart 8 is that, for each age category, the benefits received by unlawful immigrant households exceed the taxes paid. At no point in the life cycle does the average unlawful immigrant household pay more in taxes than it takes out in benefits. In each age category, unlawful immigrant households receive roughly $2.00 in government benefits for each dollar paid in taxes. Between ages 45 and 54 (generally considered prime earning years), unlawful immigrants actually receive nearly $3.00 in benefits for each dollar paid in taxes.

These figures belie the notion that government can relieve financial strains in Social Security and other programs simply by importing younger unlawful immigrant workers. The fiscal impact of an immigrant worker is determined far more by education and skill level than by age. Low-skill immigrant workers (whether lawful or unlawful) impose a net drain on government finance as soon as they enter the country and add significantly to those costs every year they remain.

Chart 8 shows the net fiscal deficits (benefits minus taxes) for each age category. The fiscal deficits reach a peak of over $19,000 per year for households with heads between 45 and 54 years old. The average deficit then falls to around $10,000 per year for households with heads between 55 and 64 years old. The number of unlawful immigrant households declines sharply with age. There are very few unlawful immigrant households with heads over age 65.

Aggregate Annual Net Fiscal Costs. In 2010, 3.44 million unlawful immigrant households appeared in the Current Population Survey. The average net fiscal deficit per household was $14,387. Most experts believe that at least 350,000 more unlawful immigrant households resided in the U.S. but were not reported in the CPS.

Assuming that the fiscal deficit for these unreported households was the same as the fiscal deficit for the unlawful immigrant households in the CPS, the total annual fiscal deficit (total benefits received minus total taxes paid) for all 3.79 million unlawful immigrant households together equaled $54.5 billion (the deficit of $14,387 per household times 3.79 million households). This sum includes direct and means-tested benefits, education, and population-based services.

Adjusting Future Deficit Estimates for the Potential Impact of the 2010 Recession

In 2010, the economy was in recession. In a recession, overall income and tax revenue will be lower; some benefits such as unemployment insurance will be dramatically higher. The recession may therefore have increased the fiscal deficit of unlawful immigrant households relative to non-recession years. However, the impact of a recession will not be uniform across all socioeconomic groups.

Evidence suggests that the recession had at best a modest impact on the fiscal status of unlawful immigrant households. For example, while incomes dropped significantly during the recession, most of the drop occurred in property income; the National Income and Product Accounts (which measure the whole economy) show that total nominal wages fell by only 2.3 percent from 2008 to 2010. Some 95 percent of the income of unlawful immigrant households comes from wages.

As measured in the CPS, the constant-dollar income of the average unlawful immigrant household was the same in 2010 as in 2006. The measured income of unlawful immigrants may be comparatively stable during a recession because unemployed unlawful immigrants return to their country of origin and thereby disappear from Census records. If the average unlawful immigrant household lost income during the recession, the drop was modest.

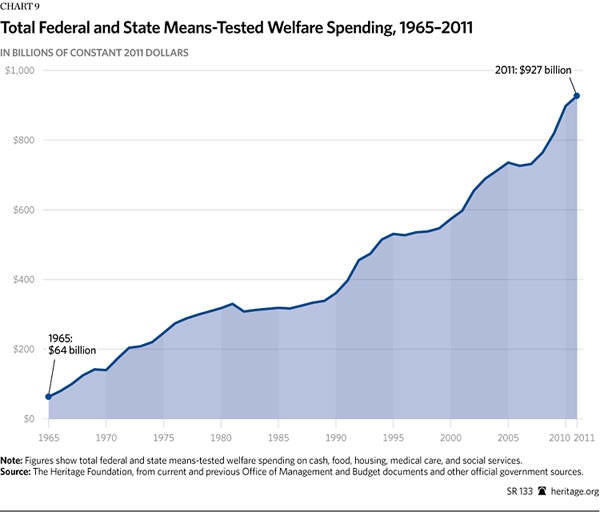

What about welfare spending? There is a popular conception that welfare spending is like a roller coaster, rising sharply during a recession and falling when the recession ends. This pattern applies somewhat to food stamps but not to means-tested welfare in general. Historically, overall means-tested spending does rise during a recession but does not fall noticeably when the recession ends.

This pattern is shown in Chart 9, which shows total means-tested spending over time adjusted for inflation. The chart shows a dramatic rise in costs over time. Periods of rapid increase are followed by spending plateaus, but there are no significant dips in post-recession periods. Following this pattern, the Obama budget shows that constant-dollar per capita means-tested spending will not decline over the next decade.[30]

Despite these caveats, the estimates of future fiscal deficits in the rest of this paper will be adjusted for the potential effects of the recession on the 2010 data. Specifically, the analysis reduces future unemployment benefits and food stamp benefits by 66 percent and 25 percent below 2010 levels, respectively. These adjustments are firmly backed by evidence and included in all of the figures on future-year deficits.

In addition, the analysis increases future tax payments by unlawful immigrants upward by 5 percent and reduces future overall means-tested welfare benefits downward by 5 percent to compensate for the impact of the recession on 2010 data. These adjustments are more speculative; their impact is shown separately in Table 7 and in subsequent tables. The latter adjustments reduce projected future fiscal deficits among unlawful immigrant households by about 5 percent.

Fiscal Impact of Amnesty or “Earned Citizenship”

In recent years, Congress has considered various comprehensive immigration reform proposals. One key feature of these proposals has been that all or most current unlawful immigrants would be allowed to stay in the U.S. and become U.S. citizens.

In most legislative proposals, amnesty or “earned citizenship” would have three phases. First, unlawful immigrants would be placed in a provisional status that would allow them to remain in the U.S. lawfully. After five to 10 years in this provisional status, most former unlawful immigrants would be granted legal permanent resident (LPR) status. After five years in LPR status, the individuals would be allowed to become U.S. citizens. The interval between initial amnesty and citizenships would thus stretch for 10 to 15 years or longer.

The fiscal impact of amnesty would vary greatly depending on the time period examined. The present paper will analyze the fiscal consequences of amnesty in four phases.

- Phase 1: Current Law or Status Quo. This is the fiscal status at the present time prior to amnesty.

- Phase 2: The Interim Phase. This phase would include the period in which amnesty recipients were in provisional status followed by the first five years of legal permanent residence. During the interim phase, tax revenues would go up as more former unlawful immigrants began to work “on the books” but would remain barred from receiving means-tested welfare and probably Obamacare health care subsidies. The overall net fiscal cost of the former unlawful immigrant population could be expected to decline slightly during this period. The length and programmatic boundaries of the interim phase would obviously vary in different bills, but five to 15 years would be typical.

- Phase 3: Full Implementation of Amnesty. At the end of the interim phase, all amnesty bills would provide the amnesty recipients (former unlawful immigrants) with full eligibility for more than 80 means-tested welfare programs as well as health care subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or Obamacare). The resulting increase in outlays would be substantial.

- Phase 4: Retirement Years. Under current law, unlawful immigrants are not eligible for Social Security and Medicare benefits. All amnesty legislation would allow recipients of amnesty to obtain eligibility for these programs. Immediately after enactment of amnesty, former unlawful immigrants with jobs would begin to acquire credits toward future Social Security and Medicare eligibility. Once they had completed 40 quarters (or 10 years) of employment, they would become eligible for Social Security old age benefits and Medicare and would begin to receive benefits upon reaching retirement age.

In addition, under amnesty, former unlawful immigrants would probably be able to obtain credits toward Social Security for work performed during their time of unlawful residence if they could show that FICA taxes were paid for that employment. Upon reaching the retirement age of 67, former unlawful immigrants could begin to draw Social Security and Medicare benefits. They would also be eligible for other government benefits such as public housing, food stamps, and Medicaid payments for nursing home care. Given the present age of most unlawful immigrants, these retirement costs would not emerge for several decades, but they would be quite large when they did occur.

The median age for current adult unlawful immigrants is 34. Given amnesty, these individuals would, on average, continue to pay taxes and receive benefits for five decades. From this perspective, placing a temporary moratorium on receipt of welfare and Obamacare subsidies would have only a marginal impact on overall costs.

Postponing the date when amnesty recipients would receive welfare and Obamacare is important politically, however, because it hides the real costs of amnesty during the all-important 10-year “budget window” employed by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Concealing the actual costs of legislation by delaying program expansion until after the end of the CBO 10-year budget window is a time-worn legislative trick in Washington. This budgetary ploy can be very effective in deluding both politicians and the public about the actual costs of legislation.

When amnesty legislation is rolled out in Congress, the public should expect to see this strategy of deception in full force. Nearly all fiscal discussion in Congress and the press will focus on the deliberately low temporary costs during the interim phase. The far more significant longer-term costs will be largely ignored. No politician who is serious about government spending and deficits should promote this deceptive budgetary gimmick, and the public should not be fooled by it.

Fiscal Changes During the Interim Phase

During the initial interim phase, amnesty would produce three fiscal changes: an increase in tax revenue, an increase in Social Security and Medicare payments for disabled persons and survivors, and an increase in some population-based costs as former unlawful immigrants become more comfortable using government services. This section analyzes those changes.

As noted earlier, nearly all experts believe that much employment of unlawful immigrants occurs “off the books.” Since taxes are not paid on this hidden employment, the result is less government revenue. After amnesty, former unlawful immigrants would have a strong incentive to shift to “on the books” employment because a consistent record of official employment would probably be necessary for these individuals to remain in the U.S. and to progress toward LPR status.

The present analysis assumes that at the current time, some 55 percent of unlawful immigrant workers work on the books and 45 percent work off the books. The analysis assumes that if amnesty were enacted, 95 percent of future employment of the former unlawful immigrants would occur on the books. This would increase payments of federal and state income taxes, FICA taxes, and other labor taxes (such unemployment and work compensation fees) by nearly $14 billion per year.

After amnesty, former unlawful immigrants would be able to seek employment more openly and compete for a wider range of positions. Research from the amnesty in 1986 shows that this led to significant wage gains among amnesty recipients, but amnesty also made individuals eligible for unemployment insurance and other programs that support individuals when they are not working, and this led to a decline in employment among workers receiving amnesty. These two effects offset each other, yielding a net overall gain of 5 percent in wages.[31] This 5 percent wage boost is included in the analysis and leads to an increase in income, FICA, and consumption tax payments of around $3 billion per year.

The analysis also assumes that after amnesty, former unlawful immigrant households would be more likely to use highways, autos, and airports; this would result in an increase in related taxes and fees of roughly $800 million per year. Overall, amnesty would increase tax revenue and fees by some $18 billion per year, or roughly $4,700 per former unlawful immigrant household.

As former unlawful immigrants began to work on the books using their own names and Social Security numbers, their eligibility for unemployment insurance benefits and workers’ compensation would increase. These benefits would likely reach levels comparable to those received by lawful immigrant families with similar socioeconomic characteristics.[32]

In contrast to old age benefits, Social Security disability, survivor’s benefits, and related Medicare are available well before retirement age. Any amnesty law would make former unlawful immigrants and their kin eligible for these benefits. For example, a worker who had five years of credited employment would receive disability benefits if he became unable to work. Ten years of credited employment would make a worker’s family eligible for survivor benefits upon the worker’s death.

Former unlawful immigrants would begin to receive these benefits not long after amnesty, and the number receiving benefits would grow over time. Eventually, the per-household disability and survivor benefits and accompanying Medicare received by former unlawful immigrant households would likely equal the benefits received by current lawful immigrants: roughly $1,600 per household per year.[33] However, during the first decade after amnesty, the benefit increase would be much less.

The present analysis assumes that unlawful immigrant households are less likely to use certain government services such as parks, highways, libraries, and airports than are lawful households with the same level of income. However, if unlawful immigrant households are granted amnesty, their utilization of these government services will increase.

Over time, the use of these services by former unlawful households would likely match their use by current lawful immigrant and non-immigrant households with similar demographic characteristics. The resulting increase in population-based government services would raise government costs by around $2,000 per household. Increased receipt of unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, disability benefits, and population-based services would increase the overall government benefits received by former unlawful immigrant households by nearly $11 billion per year.

Fiscal Impact of the Full Implementation of Amnesty

Federal and state governments currently spend over $830 billion per year on more than 80 different means-tested aid programs. U.S.-born children of unlawful immigrants are currently eligible for aid through most of these programs, but foreign-born children who are in the country unlawfully and adult unlawful immigrants are generally not eligible for aid.

At present, all amnesty proposals would make adult unlawful immigrants and their foreign-born children fully eligible for these programs at the end of the waiting period. As a result, welfare benefits in former unlawful households would likely rise to the level of those received by current lawful immigrant families with similar socioeconomic characteristics. This would mean a sharp increase in benefits from programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Earned Income Tax Credit, Medicaid, public housing, and food stamps.

Overall, annual welfare costs would rise to around $13,700 per household among former unlawful households. Amnesty would increase overall welfare costs to $51 billion per year for this group.[34]

Starting in 2014, the Affordable Care Act will begin to provide various forms of aid, including expanded Medicaid, premium subsidies, and cost-sharing subsidies, to lower-income individuals who lack health insurance. Unlawful immigrants are currently ineligible for this aid. Under amnesty or “earned citizenship,” unlawful immigrants would obtain full eligibility for these benefits, although access to aid would probably be delayed until the end of the interim period.

The estimated cost of benefits from Obamacare to former unlawful immigrant households would be $24 billion per year.[35]

Overall Fiscal Impact of Amnesty or “Earned Citizenship”

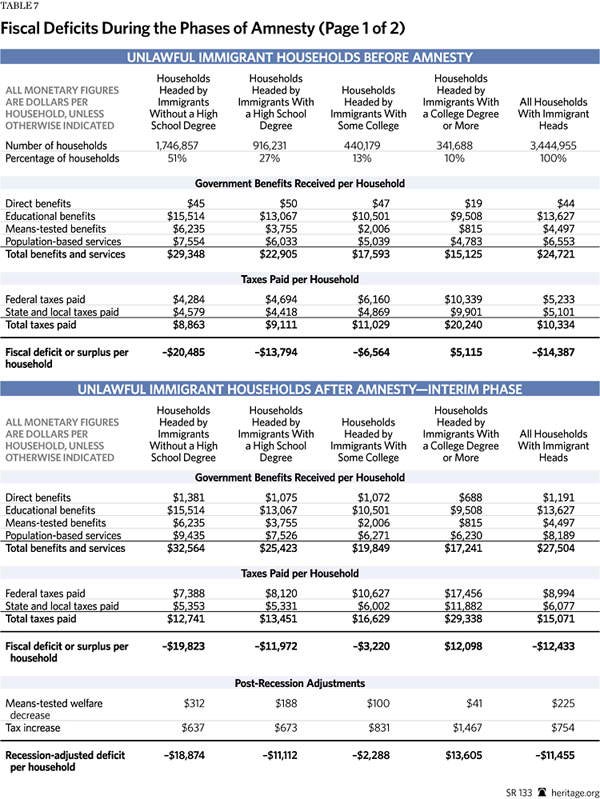

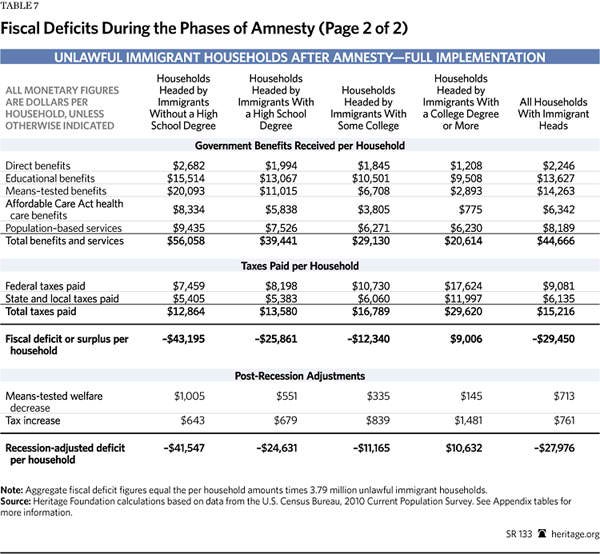

Table 7 and Chart 10 show the average fiscal balances of unlawful immigrant households during the three stages: before amnesty, the interim period after amnesty, and full implementation of amnesty. At the current time, before amnesty, the average unlawful immigrant household has a fiscal deficit of $14,387 per year. During the interim period immediately following amnesty, tax revenues would increase more than government benefits, and the average fiscal deficit among the former unlawful households would fall to $11,455 per household.[36] (This figure, however, assumes there would be no expansion of government medical care to poor amnesty recipients for a full decade after amnesty is enacted; this seems politically implausible.)

When the interim phase ends, amnesty recipients would become eligible for means-tested welfare and health care benefits under the Affordable Care Act. At that point, annual government benefits would rise to around $43,900 for the average former unlawful immigrant household.[37] Tax payments would remain at around $16,000 per household, yielding an annual fiscal deficit (benefits minus taxes paid) of around $28,000 per household.[38]

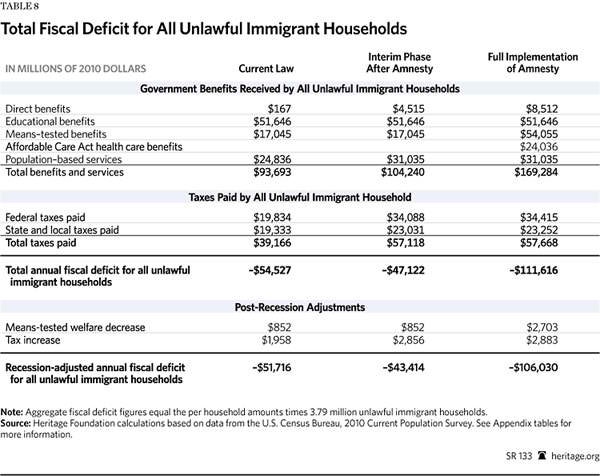

Table 8 and Chart 11 show the aggregate fiscal balance for all unlawful immigrant households in the three stages.[39] All of the figures in Table 8 and Charts 10 and 11 are adjusted for future inflation and presented in 2010 constant dollars.[40]

- Before amnesty, all unlawful immigrant households together received $93.7 billion per year in government benefits and services and paid $39.2 billion, yielding an aggregate annual deficit of $54.5 billion.

- In the interim phase after amnesty, aggregate government benefits and services would rise to $103.4 billion per year, but tax revenue would rise to around $60 billion; as a consequence, the aggregate annual deficit would fall slightly to $43.4 billion. (These figures include all post-recession adjustments.)

- At the end of the interim phase, former unlawful immigrant households would become fully eligible for means-tested welfare and health care benefits under the Affordable Care Act. Total annual government benefits and services would soar to $166.5 billion; tax revenue would remain at around $60.5 billion, yielding an aggregate annual fiscal deficit of $106 billion. (These figures include all post-recession adjustments.)

Long-Term Retirement Costs for Former Unlawful Immigrants Under Amnesty

One major fiscal consequence of amnesty is that nearly all current unlawful immigrants would become eligible for Social Security and Medicare and would receive benefits from those programs when they reach retirement age. In most cases, the few who did not obtain eligibility for Social Security and Medicare would receive support from Supplemental Security Income and Medicaid. As they aged, former unlawful immigrants would also be eligible for nursing home care funded by Medicaid. The cost of these benefits would be quite large.

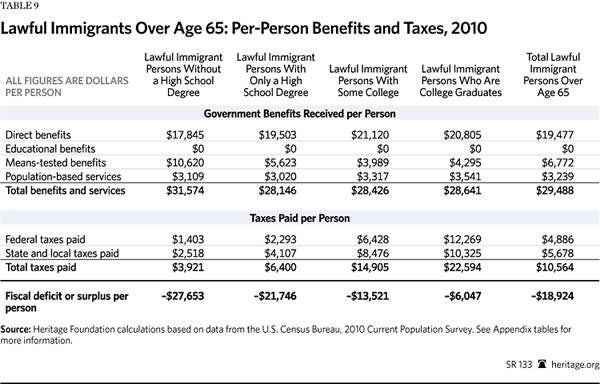

One way to estimate the future retirement costs of unlawful immigrants under amnesty is to examine the average benefits currently received by lawful immigrants over age 65 whose education levels match those of unlawful immigrants. The figures for lawful immigrants over age 65 are shown in Table 9. (Once individuals move into retirement years, it is more accurate to analyze persons rather than households. Thus, in contrast to the previous tables in this paper, Table 9 presents benefits and taxes per immigrant rather than per household.)

Table 9 reports the actual benefits received and taxes paid per person in 2010 by lawful immigrants over age 65. For example, the average elderly lawful immigrant who lacked a high school degree received $31,574 in annual government benefits and services and paid $3,921 in taxes, yielding an annual fiscal deficit of $27,653.

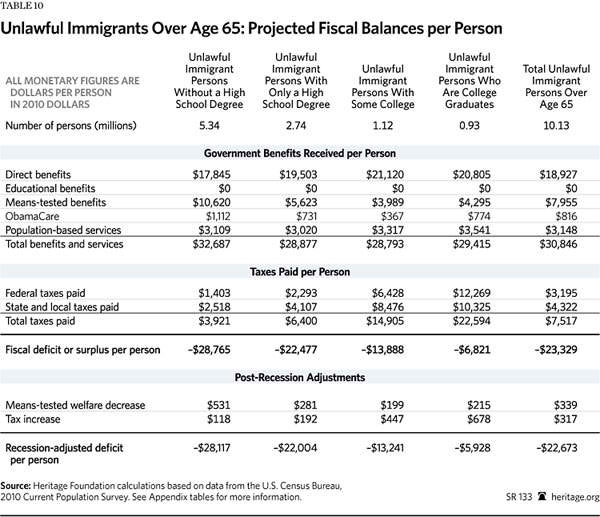

Table 10 shows the estimated fiscal balances of adult amnesty recipients over age 65 if amnesty were enacted. (Again, the estimated benefits received and taxes paid are modeled on the actual current figures for elderly lawful immigrants.) Given amnesty, the average former unlawful immigrant age 65 or older would receive around $30,500 per year in benefits. Social Security benefits would come to around $10,000 per year; Medicare would add another $9,000. Retirees would receive some $7,600 in means-tested welfare, primarily in Medicaid nursing home benefits, general Medicaid, and SSI.[41] Population-based benefits would add another $3,100 in costs. The average amnesty recipient would pay around $7,800 in taxes, resulting in an average annual fiscal deficit of roughly $22,700 per retiree.[42] (All figures include post-recession adjustments.)