Typically, the federal government defends itself vigorously against lawsuits challenging its actions. But not always: Sometimes, regulators are only too happy to face collusive lawsuits by friendly “foes” that are aimed at compelling government action that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to achieve. Rather than defend these cases, regulators settle them in a phenomenon known as “sue and settle.”

In an increasing number of cases brought by activist groups, the Obama Administration has chosen to enter into settlements that commit it to taking action, often promulgating new regulations, on a set schedule. While the “sue and settle” phenomenon is not new, what is novel is the frequency with which generally applicable regulations—particularly in the environmental sphere—are being promulgated according to judicially enforceable consent decrees. For instance, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) alone entered into more than 60 such settlements between 2009 and 2012, committing the agency to publish more than 100 new regulations at a cost to the economy of tens of billions of dollars.[1]

Perhaps greater still are the costs to political accountability. Especially in recent years, consent decrees have been used to skirt the inherently political process of setting governmental priorities.

At the most basic level, sue and settle compromises public officials’ duty to serve the public interest. Outside groups, rather than officials, are empowered to further their own interests by using litigation to set agency priorities. In some cases, consent-decree settlements appear to be the result of collusion, with an agency’s political leadership sharing the goals of those suing it and taking advantage of litigation to achieve those shared goals in ways that would be difficult outside of court.

At the same time, consent-decree settlements allow political actors to disclaim responsibility for agency actions that are unpopular, thereby evading accountability. Consent decrees also diminish the influence of other executive branch actors, such as the President and the Office of Management and Budget, and of Congress, which may use oversight and the power of the purse to promote its view of the public interest. By entering into consent-decree settlements, an Administration may also bind its successors to its regulatory program far into the future, raising serious policy and constitutional concerns.

Consent-decree settlements have also been used to short-circuit normal agency rulemaking procedures, to accelerate rulemaking in ways that constrain the public’s ability to participate in the regulatory process. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and other statutes recognize the values of notice and transparency, public participation, and careful agency deliberation—the very elements that sue and settle undermines. Settlements that resolve important questions of policy—whether to issue a regulation, the timeline for doing so, what entities will be covered, etc.—are struck behind closed doors, free from public scrutiny and input. By mandating aggressive regulatory timelines, settlements limit what opportunity for public participation remains while circumscribing officials’ ability to accommodate the comments they do receive.

Tossing the normal rulemaking procedures by the wayside is, in some sense, the very point of sue and settle: Doing so empowers the special-interest group that brought suit in the first place at the expense of parties that might otherwise use their political leverage and the rulemaking process to force compromises that serve the broader public interest.

There are, however, solutions to the sue and settle phenomenon. For example, in order to preserve its powers and discretion, the executive branch should decline to enter into consent decrees that compromise either. But such reform takes fortitude and the willingness to pass up short-term gain for less tangible, longer-term benefits such as greater public participation in rulemaking and robust democratic accountability.

It should come as little surprise that the Reagan Administration was willing to make this trade-off and that Attorney General Edwin Meese III spearheaded its policy.[2] The principles that Attorney General Meese laid out in a 1986 memorandum setting Department of Justice policy on consent decrees and settlements remain vital today and should form the backbone of any attempt by the executive branch to address this problem.

Congress can also play a critical role in these reforms. Although the ultimate decision on whether to enter into any given settlement should be left to high-ranking and accountable executive branch officials such as the Attorney General and agency heads, Congress can and should provide for greater transparency and public participation. Additionally, Congress can ensure that settlements are entered into and carried out in the public interest rather than as a means to circumvent usual rulemaking procedures or to evade accountability.

More fundamentally, though, the source of this problem—and its ultimate solution—lies with Congress. It should recognize that setting governmental priorities is an inherently political process and therefore act to limit the availability of “citizen suits” that seek to spur the government into furthering the litigants’ parochial view of the public good.

Background of Sue and Settle

The Phenomenon. “Sue and settle” is a tactic by which agencies settle cases through consent decrees that voluntarily cede lawful agency discretion. These cases typically arise from private lawsuits that seek to commit the defendant agency to issue regulations by a set deadline.

Typically, an outside group petitions the agency to undertake a rulemaking and then brings suit under either a “citizen suit” provision or the Administrative Procedure Act, which authorizes a reviewing court to “compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed.”[3] The Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act contain specific citizen suit provisions that authorize plaintiffs to bring suit to challenge an agency’s failure to perform mandatory acts under those statutes.[4] Such causes of action do not, in themselves, necessarily constrain agency discretion, but rather provide a mechanism to compel an agency to make some decision: “[W]hen an agency is compelled by law to act within a certain time period, but the manner of its action is left to the agency’s discretion, a court can compel the agency to act, but has no power to specify what the action must be.”[5]

But “failure to act” lawsuits almost always go farther than merely seeking to require the agency to act on a rulemaking petition—such as by denying it. Instead, they typically argue that the governing statute mandates that the agency regulate in a specific manner and that the agency has failed to do so. The legal basis of such a claim may be that the statute sets a deadline for regulatory action—for example, that the Food and Drug Administration propose “science-based minimum standards for the safe production and harvesting” of certain vegetables no later than January 4, 2012[6]—or that the statute requires certain substantive action—for example, as in Massachusetts v. EPA, that the EPA regulate automobile emissions of greenhouse gases because they fall within the Clean Air Act’s “capacious definition of ‘air pollutant.’”[7]

In other words, the very obligation of an agency to act is often contingent on answering some antecedent question of law or policy. Accordingly, when an agency settles such a lawsuit, it commits to issuing regulations, and that commitment often compromises the agency’s statutory discretion. For example, had the EPA settled Massachusetts rather than litigate the case, the likely consent decree would have required the EPA to issue emissions standards, committing the agency to determine that greenhouse gas emissions are a “pollutant” as that term is defined in the Act. This determination, which the Supreme Court of the United States in Massachusetts recognized may involve some degree of agency discretion,[8] would have been made by the private agreement of the parties in the settlement and resulting consent decree.

Thus, when an agency settles a “failure to act” case, that settlement decides both the threshold question of whether it ought to regulate at all and important subsidiary questions such as the targets of its regulation. It also sets agency priorities through deadlines that compel the agency to issue the regulations sought by plaintiffs, even ahead of other actions that public officials may consider to be more pressing.

Sue and settle is not confined to any particular subject matter. Many prominent cases arise under environmental statutes due to their broad, aspirational language that affords regulators commensurately broad discretion to act;[9] the high costs of the resulting regulations; and a concentrated and well-funded environmental lobby. But consent decrees binding federal actors have also been considered in cases concerning food safety, civil rights, federal mortgage subsidies, national security, and many other areas. Basically, consent decrees may become an issue in any area of the law where federal policymaking is driven by litigation.

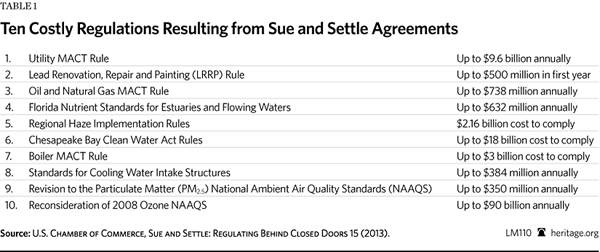

Both data and anecdotal evidence show that, under the Obama Administration, consent-decree settlements have become more frequent. A recent report by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce tallied draft consent decrees under the Clean Air Act, which (unlike under other statutes) require publication in the Federal Register.[10] The report found that the EPA had entered into some 60 consent decrees requiring the issuance of rules of general applicability during President Barack Obama’s first term—more than twice the 28 settlements of President George W. Bush’s second term. At the same time, nearly all of the Obama EPA’s most expensive rulemakings have been governed by consent decrees. This figure includes the “Utility MACT” rule discussed below, the “Boiler MACT” rule, and new air quality standards for ozone.

The Principles of Sound Rulemaking. At a minimum, the backroom dealing inherent in “sue and settle” cases conflicts with the norms of administrative rulemaking as prescribed by the Administrative Procedure Act and other statutes.[11] To begin with, the APA requires that an agency publish a proposed rule in the Federal Register. The proposal must include:

- A statement of the time, place, and nature of public rulemaking proceedings;

- Reference to the legal authority under which the rule is proposed; and

- Either the terms or substance of the proposed rule or a description of the subjects and issues involved.[12]

The agency must then “give interested persons an opportunity to participate in the rulemaking through submission of written data, views, or arguments”—i.e., a public comment period.[13] The amount of time that the agency must provide for public comment varies with the urgency and complexity of the proposed rule, from as little as 30 days for narrow, emergency fixes[14] to a year or more for complex regulatory schemes.[15] In general, courts review compliance with these requirements holistically; key is that the agency must “afford[] interested persons a reasonable and meaningful opportunity to participate in the rulemaking process.”[16]

The agency, in turn, is directed to consider the “relevant matter presented” in the comments and to incorporate in its final rule a “concise general statement” of the “basis and purpose” of the final rule. In other words, the agency must respond to comments, affording them adequate consideration and explaining how it has accounted for them. This then facilitates judicial review of the final rule to determine whether it is “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law” and therefore must be set aside.[17]

Furthermore, Congress has enacted a number of additional statutes to improve agencies’ deliberative processes and, consequently, the results of their rulemakings. For example:

- The Regulatory Flexibility Act requires agencies to evaluate the impact of proposed regulations on small businesses and consider alternatives that may prove less onerous;[18]

- The Paperwork Reduction Act requires agencies to estimate the paperwork burden of their proposals and scrap reporting requirements that are unnecessary or inefficient;[19] and

- The Unfunded Mandates Reform Act requires agencies to assess the impact of their proposals on state, local, and tribal governments and either adopt “the least costly, most cost-effective or least burdensome alternative that achieves the objectives of the rule” or explain why that option could not be adopted.[20]

Each of these statutes relies on the APA’s notice-and-comment process to inform the regulated community of proposed rules and their consequences and solicit its feedback with the goal of crafting rules that reasonably account for the circumstances of those they will govern and are no more burdensome than necessary.

Taken together, these procedural requirements “reflect Congress’ judgment that informed administrative decisionmaking requires that agency decisions be made only after affording interested persons” an opportunity to communicate their views to the agency. “Equally important, by mandating openness, explanation, and participatory democracy in the rulemaking process, these procedures assure the legitimacy of administrative norms.”[21] Attempts to circumvent these requirements necessarily undermine these values.

Sue and Settle in Action

Regrettably, when agencies enter into consent decrees that mandate accelerated rulemaking, sound policymaking often falls by the wayside. Several examples are illustrative.

EPA Utility MACT Rule. In December 2008, shortly after the presidential election, a coalition of environmental organizations sued the EPA, faulting the agency’s failure to issue emissions standards for certain “hazardous air pollutants” emitted by power plants under Section 112 of the Clean Air Act.[22] In its final months in office, the Clinton EPA had issued a predicate finding that such regulations were “appropriate and necessary,” but the George W. Bush Administration subsequently attempted to reverse that finding. Soon after the lawsuit (titled American Nurses Assoc. v. Jackson) was filed, a coalition of industry members was granted leave to intervene.

To the public, the case appeared stalled until October 2009, when the plaintiffs and the EPA concluded their private negotiations and lodged a proposed consent decree with the court. The decree stipulated that the EPA had failed to perform a mandatory duty under the Clean Air Act by not issuing a “maximum achievable control technology” (MACT) rule for power plants under Clean Air Act Section 112(d). The decree further specified that the EPA would sign a proposed rule by March 16, 2011, and would then sign a final rule no later than November 16, 2011—just eight months later.

EPA leaders, far from adverse to the plaintiffs who had initiated the suit, publicly touted the rulemaking as a signal achievement of the Obama EPA.[23] At the same time, by trading away its discretion to consider a less burdensome regulatory regime, or no regulation at all, the EPA gained political cover to issue a rule that was far more costly than might otherwise have emerged from the regulatory process.

The utility industry challenged the proposed consent decree, which the plaintiffs and the EPA had negotiated without any industry participation. The agreement unduly constrained executive discretion, the interveners argued, because it required the EPA to conclude that Section 112(d) standards would be mandated. In turn, this requirement blocked the agency from either declining to issue standards[24] or implementing standards based, in whole or in part, on health-based thresholds rather than the more onerous MACT standard.

Further, the proposed decree, they argued, all but guaranteed violations of the Administrative Procedure Act; the vast complexity of the task before the EPA could not possibly be completed in such a short period under the APA’s “arbitrary and capricious” standard.[25] As the interveners explained, the schedule contemplated by the proposal was far shorter than the EPA had employed in less complicated rulemakings that did not require the agency, as in this instance, to evaluate its proposed rule’s impact on the nation’s electric generating fleet. The public interest, it concluded, required at least 12 months for the industry and interested parties to undertake this task.

In its order and opinion approving the consent decree, the court ruled on none of these points. As to the language constraining the EPA’s discretion in the final rule, the court simply stated that the agency believed itself to be legally obligated to issue Section 112(d) standards and that “by entering this consent decree the Court is only accepting the parties’ agreement to settle, not adjudicating whether EPA’s legal position is correct.” The interveners, the court explained, could simply challenge the final rule. And with regard to the schedule, while appreciating the interveners’ position, the court refused to accord it any weight due to their status as third-party objectors: “If the science and analysis require more time, EPA can obtain it.” Ultimately, the court held that third parties are powerless to block a consent decree, even one that intimately affects their interests.[26]

Unfortunately, it appears that the interveners’ claims were, as the court acknowledged, “not insubstantial.” The EPA’s proposed rule, rushed out in a matter of months, contained numerous errors (one emission standard, for example, was off by a factor of 1,000[27]); lacked technical support documents necessary for interested parties to assess it; and was in some instances sufficiently vague that regulated entities were unable to determine their compliance obligations.[28] The EPA, in its haste, had also declined to assess the implications of its rule on electric reliability or to provide sufficient time for industry and regulators to do so—despite a statutory requirement that it take account of “energy requirements” and the possibility that the rule could conflict with requirements under the Federal Power Act.[29]

Several preliminary assessments by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and North American Electric Reliability Corporation suggested that the rule would force enough shutdowns to threaten reliability in some areas.[30] Those assessments, as well as industry evaluations, also raised the prospect that significant numbers of sources would be unable to come into compliance with the proposed standards within the three-year compliance window, even with the possibility of an additional year to achieve compliance.[31]

Late in 2011, industry interveners brought these concerns to the district court, seeking relief from the consent decree on the basis of changed circumstances—specifically, the unforeseen circumstance that, faced with overwhelming evidence that more time was necessary to craft a rule that complied with all procedural and substantive requirements, the EPA would not avail itself of the consent decree’s provision to seek the time needed to carry out its legal obligations. The court never ruled on the interveners’ motion, and the EPA signed a final rule in late December.

Regulated entities brought challenges to many aspects of the final rule, and their case is currently pending before the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The rule, meanwhile, has gone into effect at an estimated cost of $9.6 billion per year.[32]

Habitat for the Hine’s Emerald Dragonfly. The Hine’s emerald dragonfly has, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), “brilliant green eyes” and is distinguished “by its dark metallic green thorax with two distinct creamy-yellow lateral lines, and distinctively-shaped male terminal appendages and female ovipositor.”[33] In 1995, the insect was listed as endangered, and in 2004, a coalition of environmentalist groups “filed a lawsuit to stand up for the Hine’s emerald dragonfly” by forcing the FWS to provide “critical habitat” for it to breed.[34]

The agency was reluctant to do so, citing the lack of scientific knowledge regarding this particular dragonfly and the “significant social and economic cost” of removing lands from many productive uses.[35] It explained that litigation over critical habitat designations was actually distracting the agency from focusing on “urgent species conservation needs.”[36]

Nonetheless, the agency settled the case to forestall still more litigation, agreeing to an aggressive rulemaking schedule.[37] In 2007, it designated 13,221 acres in Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin as critical habitat for the dragonfly.[38] Within the year, some of the same plaintiffs filed suit again, charging that the agency had improperly excluded national forest lands in Michigan and Missouri from the dragonfly’s critical habitat.

The agency initially contested the suit, but that opposition was dropped shortly after the Obama Administration began. On February 12, 2009, the court entered a consent decree that required the FWS to revisit its decision. The agency committed to issue a new proposed rule no later than April 15 and then a revised final rule within the following year. It also agreed to pay the plaintiffs’ attorneys’ fees, totaling $30,000. A little more than a year later, the FWS issued the revised final rule more than doubling the size of the dragonfly’s critical habitat designation.

Education Funding. A final example demonstrates how sue and settle can be used to bind future policymakers to their predecessors’ policy choices.[39] In September 1980, the Carter Administration’s Department of Justice and Chicago’s public school system entered into a consent decree that required the federal government “to make every good faith effort to find and provide every available form of financial resources [sic] adequate for the implementation of the desegregation plan.”[40] The district court ruled in 1983 that the Reagan Administration had failed to satisfy this vague obligation and ordered it “to provide presently available funds, to find every available source of funds, to support specific legislative initiatives to meet the obligations of the [Chicago] Board [of Education], and ‘not [to] fail[] to seek appropriations that could be used for desegregation assistance to the Board.’”[41]

The Seventh Circuit vacated the district court’s order, taking care to interpret the consent decree narrowly on the ground that “a government’s attempts to remedy its noncompliance with a consent decree are to be preferred over judicially-imposed remedies.”[42] As to the government’s argument that its legislative activities are unreviewable by the judiciary, however, the court allowed that the district court, rather than impose a penalty for the executive branch’s lobbying Congress to cut off some funding to Chicago schools, should instead have entered a civil contempt citation that “ordered the government either to refrain from specific efforts to make desegregation funds unavailable to the Board or to inform Congress about the funding obligations of the government under the Decree” and that, if the government persisted, “criminal contempt charges might have been appropriate.”[43] The Seventh Circuit also chastised the government for actions that, “while perhaps within constitutional limits, cannot enhance the respect to which this Decree is entitled and do not befit a signatory of the stature of the United States Department of Justice.”[44]

Thus, the Reagan Administration found itself bound to an unwise and open-ended obligation willingly entered into by its predecessor.

An End Run Around Democratic Governance and Accountability

The abuse of consent decrees in regulation raises a number of practical problems that reduce the quality of policymaking actions and undermine representative government. In general, public policy should be made in public through the normal mechanisms of legislating and administrative law and subject to the give-and-take of politics. When, for reasons of convenience or advantage, public officials attempt to make policy in private sessions between government officials and (as is often the case) activist groups’ attorneys, it is the public interest that often suffers.

Experience demonstrates at least five specific consequences that arise when the federal government regulates pursuant to a consent decree.

Special Interest–Driven Priorities. Consent decrees can undermine presidential control of the executive branch, empowering activists and subordinate officials to set the federal government’s policy priorities. Regulatory actions are subject to the usual give-and-take of the political process, with Congress, outside groups, and the public all influencing an Administration’s or an agency’s agenda through formal and informal means. These include, for example, congressional policy riders or pointed questions for officials at hearings; petitions for rulemaking filed by regulated entities or activists; meetings between stakeholders and government officials; and policy direction to agencies from the White House.

Especially when they are employed collusively, consent decrees short-circuit these political processes. In this way, agency officials can work with outside groups to force their agenda in the face of opposition—or even just reluctance in light of higher priorities—from the White House, Congress, and the public. When this happens, the public interest—as distinct from activists’ or regulators’ special interests—may not have a seat at the table. Indeed, an agency may be committed to taking particular regulatory actions at particular times—actions that may be executed in advance or to the exclusion of other rulemaking activities that may be of greater or broader benefit.

Rushed Rulemaking. The public interest may also be sacrificed when officials use consent decrees to insulate the rulemaking process from political pressures that may require an agency to achieve its goals at a more deliberate speed. In this way, officials may gain an advantage over other officials and agencies that may have competing interests, as well as over their successors, by rushing out rules that they otherwise may not have been able to complete or would have had to scale back in certain respects.

In some instances, aggressive consent decree schedules, as in American Nurses, may provide the agency with a practical excuse (albeit not a legal excuse) to play fast and loose with the Administrative Procedure Act and other procedural requirements, reducing the opportunity for public participation in rulemaking and, substantively, likely resulting in lower-quality regulation. Although a consent decree deadline does not excuse an agency’s failure to observe procedural regularities, courts are typically deferential in reviewing regulatory actions and are reluctant to vacate rules tainted by procedural irregularity in all but the most egregious cases—for example, where agency misconduct and party prejudice are manifest. In practical terms, citizens and regulated entities whose procedural rights are compromised by overly aggressive consent decree schedules can rarely achieve proper redress.

Practical Obscurity. Consent decrees are often criticized as “secret regulations” because they occur outside of the usual process designed to guarantee public notice and participation in policymaking.[45] As one recent article argues, “[W]hen the government is a defendant, the public has an important interest in understanding how its activities are circumscribed or unleashed by a decree,” but too often, these settlements are not subject to any public scrutiny.[46] Even when the public is technically provided notice, that notice may be far less effective than would ordinary be required under the Administrative Procedure Act.

Consequently, the agency may make very serious policy determinations that affect the rights of third parties in serious ways without subjecting its decision-making process to the standard public scrutiny and participation. This is so despite the fact that a consent decree may be more binding on an agency than a mere regulation, which it may alter or abandon without a court’s permission.

Eliminating Flexibility. Abusive consent decrees may reduce the government’s flexibility to alter its plans and to select the best policy response to address any given problem. Recognizing the value of flexibility in administering the law, the Supreme Court has clarified that agencies need not provide any greater justification for a change in policy than for adopting a new policy.[47] It is unusual, then, that when an agency acts pursuant to a consent decree, it has substantially less discretion to select other means that may be equally effective in satisfying its statutory or constitutional obligations.

In effect, consent decrees have the potential to “freeze the regulatory processes of representative democracy.”[48] This is what the Reagan Administration learned when it entered office to find that its predecessor had already traded away its ability to adopt new approaches and respond to changing circumstances.

Evading Accountability. What the preceding points share in common is that they all reduce the accountability of government officials to the public. The formal and informal control that Congress and the President wield over agency officials is hindered when they act pursuant to consent decrees, and as this control wanes, the influence of non-elected bureaucrats grows.

At its very center, government by consent decree enshrines those special-interest groups that are party to the decree. They stand in a strong tactical position to oppose changing the decree and so likely will enjoy material influence on proposed changes in agency policy.

Standing guard over the whole process is the court, the one branch of government that is, by design, least responsive to democratic pressures and least fit to accommodate the many and varied interests affected by the decree. The court can neither effectively negotiate with all the parties affected by the decree nor ably balance the political and technological trade-offs involved. Even the best-intentioned and most vigilant court will prove institutionally incompetent to oversee an agency’s discretionary actions.[49]

The High Costs of Sue and Settle

According to the Chamber of Commerce analysis, which is based on the agencies’ own cost estimates that accompany proposed rules, consent-decree settlements struck during the first term of the Obama Administration are costing the economy tens of billions of dollars. Such an impact should come as little surprise, given that the Utility MACT rule is the EPA’s most expensive regulation ever. What is surprising, though, is how many other costly rules are the result of sue and settle.

By design, sue and settle facilitates expensive, burdensome rules.

First, as described above, it allows agency officials to evade political accountability for their actions by genuflecting to a judicially enforceable consent decree that mandates their action. As a result, officials face less pressure to moderate their approaches to regulation or to consider less burdensome alternatives. This, in turn, presents the risk of collusion and still more burdensome rules that would be politically untenable but for a consent decree.

Second, due to skirting of the notice-and-comment procedure, officials may not even be aware of alternatives.

Third, even when alternatives do present themselves, officials may lack the time to analyze and consider them—assuming, of course, that alternative approaches are not barred altogether by one or another provision of the consent decree.

In sum, it may be expected that the rules resulting from consent-decree settlements will be on the whole less efficient, more burdensome, and more expensive than those adopted through the normal rulemaking process.

In some instances, sue-and-settle litigation imposes more direct costs as the federal government commits to make payments to favored litigants. For example, the Department of the Treasury maintains the federal government’s “Judgment Fund,” a permanent, indefinite appropriation intended to pay monetary awards against the United States.[50] Often, settlements that commit the government to take action also require it to pay the “prevailing” plaintiff’s costs of litigation, including attorneys’ fees.[51] In this way, activist groups can be compensated for bringing collusive litigation intended to facilitate regulatory action. In other cases, settlements provide for payments to litigants. When such settlements rely upon novel legal theories or dubious evidence, the effective result is to authorize new government benefits while sidestepping Congress.[52] Not only do such settlements undermine transparency and accountability, but they also (like other instances of sue and settle) compromise the constitutional separation of powers.

Regrettably, due to “cryptic” reporting by Treasury, few details are available regarding most settlements that draw on the Judgment Fund in these ways. This makes it impossible to say how much money in the aggregate is being paid to the plaintiffs and attorneys who bring sue-and-settle lawsuits.[53]

Basic Principles for the Executive: The Meese Memorandum

The Carter Administration’s abuse of consent decrees and the courts’ willingness to hold the government to agreements that bound the Reagan Administration to its predecessor’s unwise policy choices led Attorney General Edwin Meese III to rethink the federal government’s approach to settlements. While a partisan might have seized the opportunity to enter into more consent decrees on every possible topic so as to entrench the present Administration’s views for years or decades to come, Attorney General Meese looked to the broader principles of the Constitution in formulating a policy that would take the opposite tack. Specifically, Attorney General Meese sought to limit the permissible subject matter of consent decrees “in a manner consistent with the proper roles of the Executive and the courts”[54] while promoting sound policymaking principles.

The Meese Policy identified three types of provisions in consent decrees that had “unduly hindered” the executive branch and the legislative branch:

- A department or agency that, by consent decree, has agreed to promulgate regulations may have relinquished its power to amend those regulations or promulgate new ones without the participation of the court.

- An agreement entered as a consent decree may divest the department or agency of discretion committed to it by the Constitution or by statute. The exercise of discretion, rather than residing in the Secretary or agency administrator, ultimately becomes subject to court approval or disapproval.

- A department or agency that has made a commitment in a consent decree to use its best efforts to obtain funding from the legislature may have placed the court in a position to order such distinctly political acts in the course of enforcing the decree.[55]

Accordingly, the Meese Policy propounded policy guidelines prohibiting the Department of Justice, whether on its own behalf or on behalf of client agencies and departments, from entering into consent decrees that limited discretionary authority in any of three manners:

- The department or agency should not enter into a consent decree that converts to a mandatory duty the otherwise discretionary authority of the Secretary or agency administrator to revise, amend, or promulgate regulations.

- The department or agency should not enter into a consent decree that either commits the department or agency to expend funds that Congress has not appropriated and that have not been budgeted for the action in question or commits a department or agency to seek a particular appropriation or budget authorization.

- The department or agency should not enter into a consent decree that divests the Secretary or agency administrator, or his successors, of discretion committed to him by Congress or the Constitution where such discretionary power was granted to respond to changing circumstances, to make policy or managerial choices, or to protect the rights of third parties.[56]

With respect to settlement agreements unsupported by consent decree, the Meese Policy imposed similar limitations buttressed by the following requirement: that the sole remedy for the government’s failure to comply with the terms of an agreement requiring it to exercise its discretion in a particular manner would be revival of the suit against it.[57] In all instances, the Attorney General retained the authority to authorize consent decrees and agreements that exceeded these limitations but did not “tend to undermine their force and is consistent with the constitutional prerogatives of the executive or the legislative branches.”[58]

The Meese Policy addresses the fundamental problem of sue and settle: It blocks agencies from relinquishing their discretionary authority to outside groups, thereby reinforcing traditional norms of administrative rulemaking. An Administration that embraces the Meese Policy will benefit from greater flexibility, improved transparency, and, ultimately, better policy results.

Suggestions for Reform

In an ideal world, the executive branch would take full responsibility for the exercise of its powers and refuse to cede its authority to the courts and private-party litigants, despite the promise of some short-term gain from doing so. Barring settlements that restrain executive discretion by statute would itself raise constitutional and policy questions and would be, in any case, incongruous with the many provisions of law that afford private parties license to compel the government to take future actions.

But Congress can and should adopt certain common-sense policies that provide for transparency and accountability in consent decrees. Any legislation that is intended to address this problem in a comprehensive fashion should include the following features with respect to consent decrees that commit the government to undertake future action of a generally applicable quality:

- Transparency. Proposed consent decrees should be subject to the usual notice-and-comment requirements, as is generally the case under the Clean Air Act.[59] To aid Congress and the public in its understanding of this issue, the Department of Justice should be required to make annual reports to Congress on the government’s use of consent decrees. In addition, the Department of the Treasury should be required to report the details of cases that result in payments by the Judgment Fund.[60]

- Robust Public Participation. As in any rulemaking, an agency or department should be required to respond to the issues raised in public comments on a proposed consent decree, justifying its policy choices in terms of the public interest; failure to do so would prevent the court from approving the consent decree. These comments, in turn, would become part of the record before the court when it rules on the consent decree. Parties who would have standing to challenge an action taken pursuant to a consent decree should have the right to intervene in a lawsuit where a consent decree may be lodged. As described below, these interveners should have the opportunity to demonstrate to the court that a proposed decree is not in the public interest.

- Sufficient Time for Rulemaking. The agency should bear the burden of demonstrating that any deadlines in the proposed decree will allow it to satisfy all applicable procedural and substantive obligations and further the public interest.

- A Public-Interest Standard. Especially for consent decrees that concern future rulemaking, parties in support of the decree should bear the burden of demonstrating that it is in the public interest. In particular, they should have to address (1) how the proposed decree would affect the discharge of all other uncompleted nondiscretionary duties and (2) why taking the regulatory actions required under the consent decree, to the delay or exclusion of other actions, is in the public interest. The court, in turn, before ruling on the supporters’ motion to accept the consent decree, would have to “satisfy itself of the settlement’s overall fairness to beneficiaries and consistency with the public interest,”[61] which supporters of the consent decree should be required to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence.

- Accountability. Before the government enters into a consent decree that contains any of the types of provisions identified in the Meese Policy, the Attorney General or agency head (for agencies with independent litigating authority) should be required to certify that he has reviewed the decree’s terms, found them to be consistent with the prerogatives of the legislative and executive branches, and approves them. In effect, Congress should implement the Meese Policy, consistent with the executive branch’s discretion, by requiring accountability when the federal government enters into consent decrees or settlements that constrain executive discretion or require it to undertake future actions.

- Flexibility. Finally, Congress should act to ensure that consent decrees do not freeze in place a particular official’s or Administration’s policy preferences, but rather afford the government reasonable flexibility, consistent with its constitutional prerogatives, to address changing circumstances. To that end, if the government moves to terminate or modify a consent decree on the grounds that it is no longer in the public interest, the court should review that motion de novo under the public-interest standard articulated above.

Each of the above-numerated principles are reflected in the Sunshine for Regulatory Decrees and Settlements Act, H.R. 1493 and S. 714. Representing a leap forward in transparency, this bill requires agencies to publish proposed consent decrees before they are filed with a court and to accept and respond to comments on proposed decrees. It also requires agencies to submit annual reports to Congress identifying any consent decrees into which they have entered.

The bill loosens the standard for intervention so that parties opposed to a “failure to act” lawsuit may intervene in the litigation and participate in any settlement negotiations. Most substantially, it requires the court, before approving a proposed consent decree, to find that any deadlines contained in the decree allow for the agency to carry out standard rulemaking procedures. In this way, the federal government could continue to benefit from the appropriate use of consent decrees to avoid unnecessary litigation while ensuring that the public interest in transparency and sound rulemaking is not compromised.

Conclusion

The Obama Administration’s increased reliance on consent-decree settlements to further its regulatory agenda is a shortsighted strategy. Whatever benefits the sue and settle model offers in the short term are undermined by the risk that poorly reasoned regulations will be struck down by the courts or reversed by a future Administration. The political benefits of evading accountability may also be fleeting as Congress and the public begin to hold the Administration and its agencies accountable for their regulatory actions.

The better course, in terms of the public interest, is for the executive branch to exercise policymaking discretion itself rather than outsourcing it to third parties. But even if the Administration continues to engage in regulation through litigation, Congress should still force agencies to honor sound rulemaking procedures.

—Andrew M. Grossman is a Visiting Legal Fellow in the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at The Heritage Foundation.