Even Swedish socialism had a dark side. Phillip Magness writes:

Although politically popular, the [Social Democratic Party]’s programs created new economic strains on the government. They imposed unprecedented expenses on the public treasury. In addition, Sweden was experiencing a declining birth rate, which portended fiscal insolvency as an aging population left the workforce and became public pensioners. If 1930s birth rate trends continued, the population of the elderly would surpass the income-generating workforce by mid-century, eventually resulting in the fiscal collapse of the entire system. [...]

Child-rearing assistance, public health care provision, paid medical leave after childbirth, housing assistance and rent subsidies for parents, and robust expenditures on public education could all be deployed to incentivize fertility, as well as socially engineer a working population that would be able to sustain its pensioners. The SDP politicians saw a double-edged sword in this approach however, as it also incentivized the poorer classes to reproduce—and at a faster rate than the wealthy. On the surface this chafed with the SDP’s emphasis on social equality. If new births disproportionately came from the lower classes [...] they could become additional drains on the public treasury by becoming lifelong dependents on the very same welfare state.

To counteract the perceived risk of welfare dependence, the SDP government consciously paired its new welfare policies with a complementary system of eugenic laws—intended to prevent or dissuade “unfit” persons from reproducing. These included a narrow compulsory sterilization program, applied to persons with hereditary “defects,” and a much larger “voluntary” sterilization program targeting behavioral considerations. As part of the latter program, the government [...] induced lower-class citizens to submit to the procedure by using the suasion and levers of the new welfare state itself.

The “voluntary” measures went far beyond involuntary sterilization, which was restricted by law to explicit eugenic reasons. As a 1997 study of the program documented, government officials are known to have used submission to “voluntary” sterilization as a condition for release from mental institutions and public hospitals, for continued access to certain forms of public housing, and even marriage licensing among the poor. In total, an estimated 63,000 Swedes were sterilized between the 1930s and the expiration of the main eugenic law in 1976. [Phillip W. Magness, “Even Swedish Socialism Was Violent,” American Institute for Economic Research, September 18]

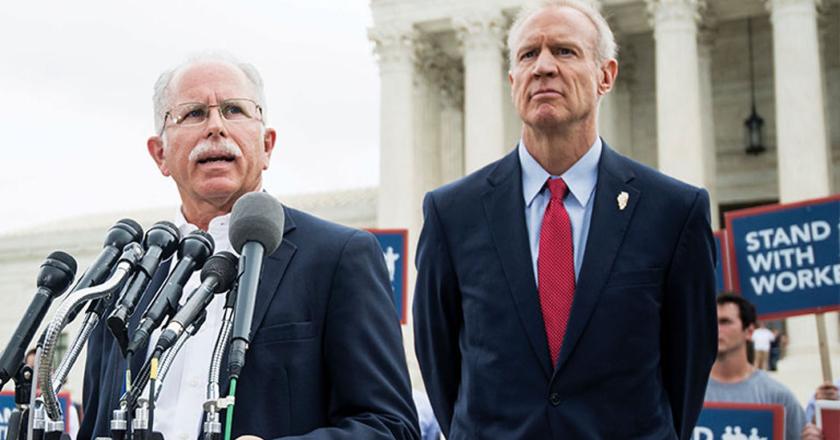

The Janus repercussions continue. States have been busy passing legislation in response to the Supreme Court’s Janus decision that ended the agency-fee setup for public employees. Some have been defensive of union privileges; others more friendly to worker rights. From Priya Brannick, here is an update on the trends in labor laws post-Janus:

Twenty-four states legally require government agencies to bargain collectively with labor unions. An additional 20 states permit collective bargaining.

Twenty-seven states provide for binding arbitration, either mandatory or at unions’ request.

Two new states, Florida and Missouri, now require incumbent government unions to go through a recertification election or process. This is in addition to Iowa and Wisconsin [...]. Still, most government unions nationwide were certified in the 1960s or 1970s when public sector collective bargaining arose and have never faced an election.

Union dues are implicitly political because they may fund ideologically partisan issues and independent expenditure committees, or Super PACs.

Only two states allow multiple unions to negotiate compensation and work conditions for public sector workers. In Missouri, employers largely determine whether teachers and police officers—who are covered by case law rather than state collective bargaining statute—may have multiple union representatives. Tennessee awards unions that earn 15 percent or more of employees’ votes proportional representation at the bargaining table. States overwhelmingly give a single union the designation of “exclusive bargaining representative” for all employees in a unit of similar workers.

Ten states have some form of paycheck protection. Five states have full paycheck protection, which we define as a complete prohibition of the payroll deduction of union dues and political contributions. These states are Wisconsin, Iowa, Michigan (for teachers and other public school employees), Oklahoma (whose 2015 statute covers state employees), and Indiana (which banned dues deductions for state workers by executive order in 2005).

Union dues are implicitly political because they may fund ideologically partisan issues and independent expenditure committees, or Super PACs. Alabama, Idaho, Kansas, Tennessee, and Utah all prohibit unions from using taxpayer-funded government payroll systems to collect political contributions or funds to be used for political purposes. Additionally, Kentucky passed a version of paycheck protection that prohibits that automatic deduction of union dues and political contributions without authorization from members.

In 2018, one new state, Missouri, joined 12 others that require union contract negotiations to be open to the public, without limiting the option of agencies to go into executive session. The others are Colorado (for public schools only), Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. Indiana also passed important new transparency measures for school district collective bargaining. While the law does not require negotiations themselves to be open to the public, school officials must call a public meeting 72 hours before a tentative proposal is ratified, and also post the proposed agreement online. [Priya M. Brannick, “Worker Freedom in the States: The Janus Impact and Grading of State Public Sector Labor Laws,” Commonwealth Foundation, August 2019]

Getty Images

Getty Images

A lack of property rights, not environmental regulation, is the real cause of forest fires in Brazil. Webb Beard writes:

[Brazil’s space research center (INPE)] claims the true cause of the unusual numbers of fires this year is ranchers and farmers using fires to clear land that they use for themselves. The INPE claimed up to 99 percent of the fires can be attributed to these people. However, this might suggest that only one thing may be to blame: the tragedy of the commons. [...]

When something is owned by everyone, such as a public highway or pond, in practice it is owned by no one. No one has an incentive to maintain or take care of the good because they receive no benefit from doing so. But when there are property rights over something,

such as the piece of land you live on, you have an incentive to take care of it because you directly benefit from it.

Economists have observed this phenomenon hundreds, if not thousands of times. Ted Turner

and buffalo ranchers brought the buffalo population back from the brink of extinction because of property rights. Fishermen almost fished the population of British Columbia halibut into extinction, and property rights brought their population back. […]

Something similar could be achieved in the Amazon rainforest. The rainforest covers part of nine countries, but roughly 60 percent of it is in Brazil. Brazil makes a claim to ownership of the Amazon. But Brazil and the other countries don’t have the resources or proper incentive structures to take care of the Amazon. The answer could be property rights. [Webb Beard, “How Property Rights Can Help Preserve the Amazon Rainforest,” Foundation for Economic Education, August 28]

Getty Images

Getty Images

States are using Obamacare waivers to reduce premiums. Doug Badger writes:

Average premiums for benchmark plans—exchange-based policies whose rates are used to compute federal premium subsidies—were 76 percent higher in 2018 than in 2014. That trend did not continue in 2019, when premiums for benchmark plans fell by 0.83 percent, the first such decline recorded.

That result defied forecasts of double-digit premium increases, which many analysts predicted would result from repeal of tax penalties on the uninsured and liberalization of federal rules governing short-term, limited duration policies. The Congressional Budget Office, for example, projected that 2019 premiums would rise by an average of 16 percent as a result of those and other changes.

The standard explanation for why these predictions proved erroneous is that insurers “overshot” their rate hikes in 2018 and adjusted them downward in 2019. While broadly correct, [there is] another critical factor. [...]

[P]remiums declined significantly in the seven states that obtained federal waivers to operate risk-stabilization programs (median reduction of 7.48 percent), and increased in the 44 states and the District of Columbia that did not have such waivers in place (median increase of 3.09 percent). [Doug Badger, “How Health Care Premiums Are Declining in States that Seek Relief from Obamacare’s Mandates,” The Heritage Foundation, August 13]

Getty Images

Getty Images

Natural gas is a booming industry for the United States. Nicolas Loris writes:

According to a new report published by the International Energy Agency, the United States could become the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas as soon as 2024. [...]

Before the shale revolution, it appeared as though the United States would become a massive natural gas importer. In fact, the most recent export terminal built in Louisiana in 2008 was originally constructed as an import terminal.

However, smart extraction technologies created an economic boom and catapulted the United States to be the world’s largest natural gas producer for more than a decade. Last year, the United States produced more natural gas than the entire Middle East combined.

The industry is expected to support 3 million jobs by next year. This new energy market will also contribute $62 billion in federal and state tax revenues in gas-producing states.

Along with leading the way in natural gas production, the United States is increasingly becoming a global leader in natural gas exports.

According to the Department of Energy, in 2018, the United States exported 700 billion cubic feet of liquefied natural gas to 27 countries on five continents. Japan currently accounts for 37 percent of the global liquefied natural gas market, but China’s growing energy needs will soon make that country the largest importer of liquefied natural gas in the world. [...]

A strong liquefied natural gas trade policy that removes burdensome regulations and empowers the states will strengthen our global energy leadership and protect our allies abroad

from manipulative energy suppliers, such as Russia and Iran. [Nicolas Loris, “How Natural Gas Exports Are Giving America a Key Edge,” The Daily Signal, July 29]

Getty Images

Getty Images

Dependency is down. John Merline writes:

As of June, there were 5.6 million more people with jobs than when President Trump took office—despite claims by prominent economists that the economy was already at full employment when he was sworn in.

The healthy labor market has resulted in something even more important yet little noticed: A sharp trend away from dependency on federal welfare and other benefits.

Take a look at the numbers:

Food Stamps. The Department of Agriculture reports that April enrollment in food stamps—which is officially called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—was down more than 308,000.

So far this year, SNAP enrollment has declined by nearly 1.2 million. And since Trump took office, the number of people collecting food stamps has plunged by more than 6.7 million.

Enrollment is now lower than it’s been since August 2009.

Disability. The number of workers on Social Security’s Disability Insurance program has sharply declined as well. It went from 8.8 million in January 2017 to 8.49 million as of May. That’s the lowest it’s been since August 2011.

Some of that decline is because beneficiaries who turn 65 shift over to regular Social Security. But the data also show that new disability applications are down. Average monthly applications for SSDI this year is 9 percent below where it was in 2016, government data show.

The healthy labor market has resulted in something even more important yet little noticed: A sharp trend away from dependency on federal welfare and other benefits.

Medicaid. Enrollment in Medicaid also has dropped sharply since Trump took office—despite the fact that Virginia decided to expand its program under Obamacare, which added some 300,000 to its Medicaid rolls over those years.

As of this March, the total number of people on Medicaid and [the Children’s Health Insurance Program] was down by 2.5 million.

Obamacare. The number enrolled in Obamacare has declined every year since Trump took office as well, and is now 1 million below where it was at the end of 2016.

Welfare. The number of those collecting welfare—either on the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or what are called “separate state programs”—has dropped by more than 800,000 under Trump. [John Merline, “Government Dependency Plunges Under Trump—Why Aren’t We Celebrating?” Issues and Insights, July 7]

Getty Images/Chip Somodevilla/Staff

Getty Images/Chip Somodevilla/Staff

Most government is unconstitutional. Nick Sibilla writes:

The U.S. Supreme Court made it much easier for federal agencies to create new crimes and prosecute them, rejecting a constitutional challenge based on the separation of powers. In an unusual split that saw Justice Samuel Alito join the Supreme Court’s liberal wing, Gundy v. United States upheld the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA), a “comprehensive national system” Congress established in 2006 to register sex offenders, which gave the attorney general vast powers of rulemaking and enforcement. [...]

Thanks to SORNA’s broad transfer of power, the Justice Department previously acknowledged that the attorney general “could require some but not all to register (or comply with some but not all of the registration requirements); he could do nothing at all or wait several years before acting; or he could change his mind at any given time or over the course of different administrations.” Moreover, SORNA “does not require the attorney general to act within a certain time frame or by a date certain; it does not require him to act at all.”

Yet under the Constitution, “all legislative powers” are “vested” in Congress, while Congress cannot “delegate” or outsource those powers to another branch of government. As anyone who’s seen “Schoolhouse Rock” may recall, the federal government is a system of checks-and-balances: The legislature (Congress) makes the law, the executive (president) enforces the law, and the judiciary (Supreme Court) interprets the law. [...]

As [Justice Neil] Gorsuch argued, letting the attorney general “write the criminal laws he is charged with enforcing” would “mark the end of any meaningful enforcement of our separation of powers and invite the tyranny of the majority that follows when lawmaking and law enforcement responsibilities are united in the same hands.”

“If the separation of powers means anything, it must mean that Congress cannot give the executive branch a blank check to write a code of conduct governing private conduct for a half-million people,” he added.

Justice Elena Kagan didn’t agree. [...]

Kagan called the delegation at stake in Gundy “distinctly small-bore.” “Indeed, if SORNA’s delegation is unconstitutional, then most of Government is unconstitutional—dependent as Congress is on the need to give discretion to executive officials to implement its programs,” Kagan quipped.

Of course, for many Americans that would be a feature, not a bug, of a reinvigorated nondelegation doctrine. [Nick Sibilla, “Gorsuch Slams the Supreme Court for Turning a Blind Eye to Overcriminalization,” Forbes, June 21]