One of the most crucial factors that determine a child’s ability to move up the economic ladder is education. Today, completing high school is essential for any chance to achieve financial success in life. College experience is important, but failing to graduate from high school is likely to be economically disastrous. Despite the overwhelming evidence that high school completion leads to greater earnings and happiness in adulthood, thousands of students drop out every year, due to a variety of factors. This Discussion Paper examines barriers to high school completion that create barriers to economic mobility.

The question is not whether a child is intelligent enough to complete high school. With the proper resources and support, almost every child is capable of earning a high school diploma. The question is which skills a student must develop in order to succeed in high school. Despite recent upward trends in high school graduation rates, it is still unclear whether students are developing the non-cognitive skills during high school that will enable them to survive setbacks, including during their high school career, and to persevere through life’s challenges in order to prosper economically and socially. If one can identify the non-cognitive skills that are needed to succeed in school, and how to foster them, high school completion rates can increase. Social skills, perseverance or “grit,” ambition, and a strong set of values are all components of a child’s personality that are essential to success. However, many schools—especially public schools serving low-income communities—fail to develop these skills and leave their students with the options of dropping out or graduating with a meaningless diploma. As the late Gary Becker, a Nobel-prize winner in economics, wrote, “The degree of mobility would increase significantly if ways could be found to efficiently lower the high school dropout rate.”[1] Indeed, economic mobility for low-income children would greatly improve if they could achieve the significant step of earning a (meaningful) high school diploma.

In order improve high school graduation rates and education quality across the country, the first thing to do is to identify who drops out of high school and why. Then, policymakers can investigate how to nurture an environment conducive to education in schools and communities to foster the non-cognitive skills needed for success. Teachers, parents, and school administrators must pay special attention to the non-academic reasons a child may have for underperforming in school, such as family, neighborhood, or community influences. Once these factors are identified and considered, better policies can be implemented to remove the barriers to high school completion.

Why Education Is Necessary for Economic Mobility

In order for a child in any income bracket to achieve financial stability as an adult, he must be brought up in a strong educational environment. Economic mobility requires different forms of “capital.” Stuart Butler, Bill Beach, and Paul Winfree write that social, financial, and human capital are all indicators of upward economic mobility. Social capital may be gained from interactions with one’s family or community that provide the framework for success. Financial capital can be passed from parents to children through savings and wealth accumulation. Human capital, the skills and traits one earns through education, is invaluable for economic mobility. The Pew Research Center finds that “[e]ducation is the largest known factor in explaining the connection between parents’ earnings and their children’s.”[2]

There is growing concern over the low social and human capital accumulated by many young people in the United States, with educational quality at the forefront of the debate. In order to improve educational outcomes in the United States, special attention must be paid to social and cultural factors that contribute to a child’s ability to succeed. Even a child from the wealthiest family can drop out of high school if he or she is not given proper guidance or support from family, community, or school. Indeed, social capital and social mobility, rather than income inequality, should be the focus of current debates over economic mobility.

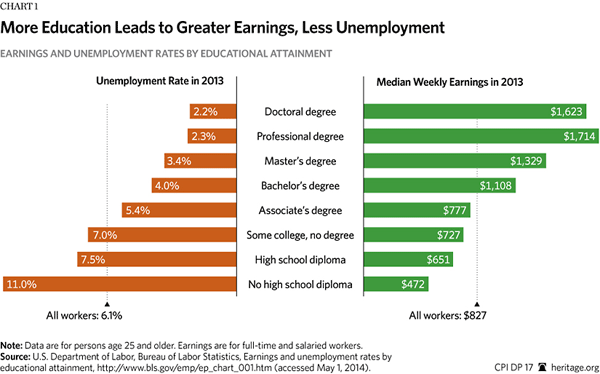

While family and neighborhood conditions heavily influence the future prospects of children, parental education levels or family income need not be the defining factor in a child’s ability to move up the economic ladder. Failing public schools set up their students for failure in life. The Pew Economic Mobility Project has analyzed a wide variety of factors affecting the probability that a child will move up the economic ladder as an adult. Pew cites educational attainment as critical, finding that “those who graduate from college with a bachelor’s degree will make an average of 70 percent more than those with only a high school diploma.”[3] But, the earnings of those with a high school diploma are significantly higher than for those without. Anthony Carnevale of Georgetown University found that a “high school dropout can expect to earn $973,000 over a lifetime. Someone with a high school diploma can expect to earn $1.3 million over a lifetime.”[4] So, students must be encouraged to finish high school if there is to be any change in higher education attainment and, hence, upward mobility for millions of young Americans. The Manhattan Institute’s Diana Furchtgott–Roth, citing the Bureau of Labor Statistics, explains that “getting children to complete high school raises average weekly incomes by $9,400 a year.” Similarly, the nonpartisan partner of the National Governors Association, Achieve, Inc., found:

Thirty years ago, most teenagers who dropped out of high school could expect to find a well-paying job, and most who worked hard could expect to climb the economic ladder. But the world has changed. Today, high school dropouts face diminishing opportunities and a lifetime of financial struggle. In fact, the median earnings of families headed by a high school dropout declined by nearly a third between 1974 and 2004.[5]

Yet, despite the economic necessity of a meaningful education, a significant number of students still drop out of high school every year, slashing their future earnings potential significantly.

Not only do high school dropouts jeopardize their chance at achieving upward mobility, but studies show that their children will have problems moving up the economic ladder as well. Pew finds that “[e]ducation explains about 30 percent of the relationship between the income of parents and their children, more than any other observable factor.… [O]ut of every 100 high school students, roughly 50 will make it to college.” High dropout rates hurt the economy significantly. In 2001, 40 percent of high school dropouts received federal aid. Additionally, the government spends between $1.7 million and $2.3 million per dropout who turns to drugs or crime over the course of his lifetime.[6] Overall, “high school dropouts may—taken together—represent billions of dollars annually in lost revenue for the U.S. economy.”[7] It is in the interest of the nation to identify students who are at risk for dropping out and help them stay on the right path. In order to end the cycle of social immobility, policymakers must remove the barriers to high school completion that exist in the American education system.

How can that be done? Reviewing the research on success, Paul Tough argues in his book How Children Succeed that it is not pure knowledge or intelligence that allows a child to complete high school and attend college.[8] Specifically, Tough emphasizes the need for schools to build character, because therein lies the secret to success. Developing skills such as self-control, will power, self-discipline, motivation, and the University of Pennsylvania’s Angela Duckworth’s well-documented “grit,”[9] significantly contribute to a child’s future success. Duckworth defines grit as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Grit entails working strenuously towards challenges, maintaining effort and interest over years and despite failure, adversity and plateaus in progress.”[10] Given the difficult and oftentimes tedious nature of academia, a student must have grit to appreciate the value of his education. Tough writes, “Grit, Duckworth discovered, is only faintly related to IQ—there are smart gritty people and dumb gritty people—but at Penn, high grit scores allowed students who had entered college with relatively low college-board scores to nonetheless achieve high GPAs.”[11] When given the right tools, “gritty” students can succeed in the classroom. We must develop programs that foster character building among potential dropouts.

Who Drops Out of High School?

The best-known group that is at risk for dropping out of high school is boys. Boys consistently drop out of high school at a higher rate than girls, with male dropout rates higher than those for females in every single state. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the female graduation rate in 2012 was 85 percent, while the male graduation rate was just 78 percent.[12] This has had very negative impacts on men’s economic standing. A Brookings Institution report found that since the 1970s, the “earnings of the median male high-school dropout who works full time have declined by 38 percent, while the earnings of the median male with only a high-school degree have fallen by 26 percent.”[13]

While the general pattern of incomes over the period is a matter of debate, this pattern of divergence is large and very troubling. Clearly, more attention should be paid to the specific problems that young men are facing in school. American Enterprise Institute scholar Christina Hoff Sommers goes so far as to claim this pattern is effectively a “war against boys” being waged in America’s public schools.[14] She argues that schools need to acknowledge that girls and boys are different. Hoff Sommers is a strong advocate of vocational programs aimed at keeping boys in high school, despite strong opposition from women’s advocacy groups.

Second, there is a large difference in the dropout rate among racial groups, often referred to as the racial achievement gap. For decades, black and Hispanic children have been performing much worse in school than their white or Asian counterparts. Disturbingly, this gap is now seen by many educators as a pre-determined given, without a proper focus on its causes. For the 2011–2012 school year, the adjusted cohort graduation rates (ACGR)[15] for black and Hispanic students were 69 percent and 73 percent, respectively. This is starkly different from the ACGR of white students, at 86 percent, or Asian students, 88 percent.[16] The achievement gap discourages many students from thinking they could ever succeed in school. Social science research indicates that this creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, meaning that the presence of the achievement gap has a strong psychological effect on minority children: “Self-fulfilling prophecies can have long-term and negative influences on the outcomes of targets who are perceived unfavorably, ultimately widening the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged groups.”[17] It is the achievement gap itself, regardless of its initial cause, that can cause students to expect little from themselves. In conjunction with a lack of expectations at home, children can easily lose motivation to succeed academically.

The third group at high risk of dropping out is children who come from poor homes. Children from low-income families find it extremely difficult to achieve the same quality of education as their middle-class peers. In the 2011–2012 school year, the ACGR for economically disadvantaged students was 72 percent, compared to the national average of 80 percent.[18] Sean Reardon’s 2011 study revealed that a parent’s income may be a much higher predictor of a child’s educational attainment than many other factors that were previously held to be high predictors, such as the parents’ education level or race. Reardon found that the “achievement gap between children from high- and low-income families is roughly 30 to 40 percent larger among children born in 2001 than among those born twenty-five years earlier.”[19] In contrast to the racial achievement gap, which has been slowly but surely closing over the past 50 years, the income achievement gap seems to only have gotten worse.

Barriers to High School Completion

Low-Quality Schools. Liberals and conservatives alike agree that many parts of the public school system in America are failing, especially in low-income communities. Too many young students are trapped in failing public schools simply because of where they were born. Place of birth should not be a life sentence to low economic mobility. The Brookings Institution Education Choice and Competition Index highlights the poor opportunities that American children face all over the country, especially in public schools.[20]

Public high school graduation rates are on an upward trend, reaching 80 percent[21] in 2012, an achievement that should be celebrated with caution. Graduation rates alone are not a reliable indicator of a quality education and future success. It could be that while completion rates have slightly increased, the value of a high school degree has not. Indeed, according to the American Diploma Project, launched by the Achieve Organization, more and more students are heading to college without the skills necessary to complete college coursework. Over half of college students take a remedial English or math class.[22] Students who go directly from high school to the workforce are not faring much better. The American Diploma Project finds that employers are also disappointed that high school graduates are not skilled for the jobs for which a high school diploma should qualify them: “More than 60 percent of employers rate graduates’ skills in grammar, spelling, writing and basic math as only ‘fair’ or ‘poor.’”[23]

Family Conditions. It is a fact that children need a stable home in order to succeed in the classroom. Students often find it difficult to focus on schoolwork when their family life is stressful. Indeed, the best safeguard against child poverty is two-parent families. Research indicates that family structure in America has shifted dramatically over the years. According to the Pew Economic Mobility Project, the percentage of children born to single mothers has been rising since the 1950s.[24] The evidence shows that a single-parent household tends to have a negative impact on a child’s economic mobility. Pew found that “regardless of race, children raised in single-parent households are more likely to live in poverty and are less likely to do well in areas that influence future economic mobility, such as educational attainment.”[25] Even if a child is lucky enough to attend a high-quality public school, his future may still be in jeopardy if he was not raised in a stable family structure.

Boys are more affected by unstable family structure than girls, adding to their risk of dropping out. As Isabelle Sawhill and others at the Brookings Institution have written, children born to poor, never-married mothers face enormous problems in school and later life.[26] Similarly, Michael Jindra of the Institute for Family Studies notes that “among less educated Americans, men raised by single parents are unlikely to reap the gains of a lasting marriage themselves.” Moreover, for young men, “unstable family dynamics lead individuals to seek connections and groups where they can fit in, and contemporary society offers a plethora of subcultures that supply this need. In the inner city, gangs are often a family substitute, a way to connect with other males. White working-class males are prone to take on a ‘southern rebel identity’ that rejects middle-class roles and education, career, and family.”[27] Such behaviors can make it very difficult to succeed in school.

Parents serve as irreplaceable role models for their children. Children who see their parents work hard and take advantage of their educational attainments are more likely to see the value in education. Conversely, if parents do not stress the importance of education and consider dropping out an acceptable alternative, children are likely to act accordingly.

Social and Neighborhood Factors. The zip code a child is born into should not determine his future earnings. The community culture and expectations of an entire neighborhood have significant effects on a child’s ability to succeed in school and in life.

In his book Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960–2010,[28] the American Enterprise Institute’s Charles Murray paints a bleak picture of the drastic effects that increasingly polarized neighborhoods generally have on children’s success. In Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality,[29] New York University sociologist Patrick Sharkey similarly discusses how a very poor neighborhood can produce barriers to economic mobility due to a unique combination of social factors. The evidence that a child’s neighborhood can have lasting effects on mobility is staggering. Sharkey found that “[in] neighborhoods where less than 10 percent of the population was poor; the typical child who started in the bottom two income quintiles had a 61 percent chance of moving up one quintile in adulthood. If those children had grown up in a neighborhood with a poverty rate of 20 to 30 percent instead, only 50 percent would have been upwardly mobile.”[30] Why is it that children who come from poorer neighborhoods have significantly lower chances at upward mobility? The best explanation may be that a child’s choices and prospects result from a combination of peer pressures, whether from friends, schools, gangs, or parents. In one of the studies for the Pew Economic Mobility Project, former director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Data Analysis William Beach and his co-authors note that “peer interactions may reinforce negative behavior. There has been growing concern among middle-class African American parents, for instance, that their efforts to raise the expectations of their children and encourage success at school are blunted by discouraging peer pressure among other African American children—especially boys—at high school.”[31]

Such patterns are evident in inner city public schools, such as those in Washington, D.C. The District of Columbia has one of the lowest high school graduation rates in the country, at just 59 percent in 2012.[32] This low graduation rate comes in tandem with a dismally low culture of expectations. If a child’s parents, friends, and neighbors never graduated from high school, and no one expects him or her to be any different, this child will have very low life goals. The Heritage Foundation’s Stuart Butler writes that a culture of expectations has an extremely strong effect on a neighborhood and those who live in it. High schools in particular have a unique way of shaping a child’s path in life, says Butler: “If the culture at a high school encourages immediate gratification rather than studying and working for good grades, or if gangs in a neighborhood are strong while churches and other supportive associations are weak, the research indicates that a young person is very unlikely to do well in life.”[33] Harvard’s Roland Fryer describes how the social stigma associated with being a good student can discourage young blacks and Hispanics in certain school settings from succeeding.[34]

While many children are frustrated when their parents constantly push them to succeed, it turns out that those children will be much better off in life than those whose parents or peers expect little of them.

Drug Markets. Drugs act as a barrier to students completing high school and disproportionally affect minority and low-income students—directly, through the drug use itself, and indirectly, by becoming entangled in the juvenile justice system. Too many teens find themselves in serious trouble with the law or with school due to drug use. Anna Aizer of Brown University and Joseph Doyle of MIT have found that “four of every five children and teens (78.4 percent) in juvenile justice systems … are under the influence of alcohol or drugs while committing their crime, test positive for drugs, are arrested for committing an alcohol or drug offense, admit having substance abuse and addiction problems, or some share combination of these characteristics.”[35]

If a student gets caught up in drugs, his or her priorities quickly move away from school. Students will often skip class, lose any motivation to succeed, and do not develop such habits as saving money for future use. All of these traits represent reduced non-cognitive skills, or “grit.” Pew found, “Seventy-one percent of children born to high-saving, low-income parents move up from the bottom income quartile over a generation, compared to only 50 percent of children of low-saving, low-income parents.”[36] The very act of saving money also represents a kind of responsibility and maturity, the kind needed to prepare for success in the future. Drugs destroy a child’s ability to focus on developing such important tools for success.

High school drug users are found disproportionately among minority and low-income students. While teenagers of all races use drugs, minority youths are arrested far more often for drug-related crimes.[37] This may in part explain the disparity between white dropout rates and black and Hispanic rates. In a recent study, William Evans of Notre Dame University, Craig Garthwaite of Northwestern University, and Timothy Moore of George Washington University write, “Our results show that crack markets explain most of the stalled progress in black male educational outcomes.”[38] Crack cocaine in particular plagues high schools across the country and contributes greatly to the racial achievement gap: “Differences in male graduation rates narrowed before crack cocaine arrived, in line with literature on convergence. The 18-year-old black male graduation rate starts to fall two years after crack markets emerge.”[39] The entire culture surrounding the drug market, particularly crack cocaine, creates a strong barrier to mobility by getting in the way of education.

The barriers extend beyond simple addiction: “Crack markets had three primary impacts on young black males: an increased probability of being murdered, an increased risk of incarceration, and a potential source of income. Each limits the benefits of education.”[40] Aizer and Doyle also found that 53.9 percent of teens who are arrested test positive for drugs at the time of their arrest, suggesting that drug use may have influenced the inclination to commit a crime.[41] Students who get involved in drug dealing also see immediate financial gains that undermine the sense of value associated with their education. The culture that surrounds drug use undermines the values of hard work and delayed gratification that teens should gain from a high school experience.

Violence in School. Violence in schools does not receive nearly as much attention as it deserves. It may be a major reason for students dropping out of high school. The KIPP School’s Benning Road Campus in Washington, D.C., found that unless they provided safe passage for their students between home and school, children would not come to school. So the school worked with local law enforcement to get drugs and crime off the local streets so students could walk to school safely and focus on their education.[42]

Unfortunately, gang violence dominates inner city schools, which further divides classrooms and creates hostility, a problem that particularly involves male students.

Parental concern over gang violence reached a new level recently in Chicago when the city closed almost 50 low-enrollment public schools. Students who had attended these schools were required to attend different schools and travel farther, and through different neighborhoods, to get to school. This would simply boil down to an inconvenience if not for the horrifying gang violence that followed. Despite the creation of Chicago’s “Safe Passage Zones,” which were meant to offer students a safe route to school, violence plagues Chicago’s youngsters and afflicts many neighborhoods. Last December, a 15-year-old girl was brutally beaten and raped about a half a block from a Safe Passage Zone. Chicago parents are increasingly concerned about the safety of their children, considering that “about 12,000 students are attending new schools this year because of the budget crisis, and many of them must walk through some of Chicago’s most violent neighborhoods.”[43] Safety is not just a problem that plagues Chicago. A survey of parents whose children are enrolled in the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program indicated safety as the number one factor they consider when choosing a school.[44]

What can be done to mitigate the effect of violence on attendance and graduation? Jeffrey Sprague at the University of Oregon and his co-authors trace the effects of school violence intervention in two middle schools that suffered from high rates of violence, crime, and student dropouts. In the first school (the “treatment school”), in a city in the northwestern U.S., the researchers adopted the Student Wide Positive Behavior Support (SWPBS)[45] program as well as the Second Step program[46] to reduce school violence. They then compared the effects to a second school (the comparison school) in the same city, which only adopted SWPBS. Both schools “showed reductions in relative percentage of total overt aggression and covert behavior…. However, the treatment school showed a higher reduction (-35 percent) in overt aggression than the comparison school (-26).”[47] SWPBS provides a clear definition of what is expected of the students, and a clear definition of unacceptable behavior as well as the consequences. It provides regular instruction on positive social behaviors, staff training, data-based feedback, and coaching on effective implementation and intervention. The second program, Second Step, is a Web-based information system that advises schools on how to design school-wide and individual student interventions. Both schools benefited greatly from the anti-violence measures they implemented. The success of these programs stems from their attention to behavioral patterns, rather than academic abilities. It is the development of non-cognitive skills such as perseverance and obedience that cause students to behave appropriately in school and graduate.

The Center for Neighborhood Enterprise (CNE), founded by Robert Woodson, the “godfather” of promoting social change through neighborhood organizations, has addressed the problem of youth violence in low-income communities since the 1980s. Before the CNE’s intervention in the Benning Terrace neighborhood in Washington, D.C., high-school-age teens could hardly avoid the gang-ridden lifestyle. After a 12-year-old boy was killed in a gang dispute, Woodson and his organization stepped in to “help craft a peace agreement between the factions whose conflicts had caused more than 50 youth deaths in years before.”[48] The peace agreement used techniques developed by the CNE from its experience with gang violence in Philadelphia, calling on former gang leaders themselves to help stop the violence. The success of the intervention in Benning Terrace spread first to a high school in Dallas and is now implemented in over 30 troubled high schools across the country.[49]

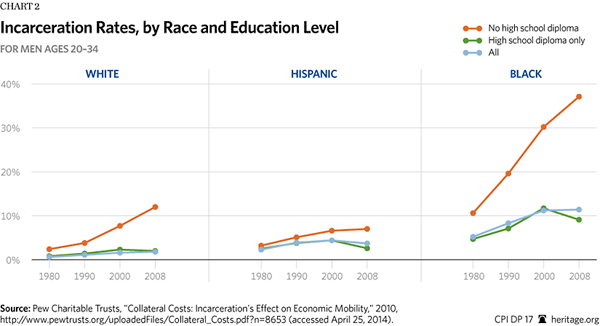

Incarceration. Drug use, gang membership, and school violence often lead to incarceration. Instead of addressing the problem of violence in schools first-hand, the current approach is merely to lock up these young people. But whatever immediate improvement that may achieve in the neighborhood, it typically ruins the long-term prospects of the incarcerated and does not resolve the root cause of school violence. The United States incarcerates more people than any other country and the prison population consists overwhelmingly of racial minorities. The Pew Economic Mobility Project argues that incarceration is detrimental to economic mobility after release, a problem that significantly affects young black men without a high school diploma. “More young (20 to 34-year-old) African American men without a high school diploma or GED are currently behind bars (37 percent) than employed (26 percent),” stated Pew.[50] It is crucial, therefore, to focus on how schools can help young black and other teens in tough neighborhoods to develop the personal traits that will improve their future opportunities.

It is extremely difficult to rebound from trouble with the law as a teen. Aizer and Doyle found that “those incarcerated as a juvenile are 39 percentage points less likely to graduate from high school and are 41 percentage points more likely to have entered adult prison by age 25 compared with other public school students from the same neighborhood.”[51] Even being charged with a crime, without going to prison, can hurt one’s future. The same study found that being merely charged with a crime in court decreases high school graduation by 13 percentage points, and increases chances of being incarcerated as an adult by 22 percentage points. Research by Gary Sweeten at Arizona State University indicates that a “first time arrest during high school nearly doubles the odds of dropout.”[52]

According to the Fight Crime: Invest in Kids Organization, “High School Dropouts are three and one-half times more likely than high school graduates to be arrested.”[53] There is now strong evidence that links higher graduation rates to a reduction in murders and assaults. The same organization found that “[i]ncreasing the nation’s graduation rates from an estimated 71 percent to 81 percent, therefore, would yield 400,000 more graduates annually and prevent more than 3,000 murders and nearly 175,000 aggravated assaults each year.”[54]

Schools need to make sure that at-risk youth do not get distracted and commit crimes that would prevent them from graduating and place themselves in trouble with the law.

Can a GED Make Up for Dropping Out?

Since prevention is generally much better than cure, it might be thought that successfully encouraging school dropouts to obtain a General Educational Development certificate (GED) can make up for lost ground in high school. That does not tend to be the case—which provides additional insights about the importance of non-cognitive skills for success.

States adopted the GED as a “second chance” option for dropouts who wanted to receive a high school credential without finishing high school or after dropping out. However, the evidence seems to suggest that the availability of a GED certification does not encourage further educational attainment, and may actually encourage students to drop out of high school.

Research conducted by the University of Chicago’s James Heckman, for instance, found that students who received their GED are not all that different than high school dropouts in their future life trajectory.[55] Heckman attributes this to similar lack of motivation and non-cognitive skills that tend to lead to dropping out school. Heckman and others found that while students who take the GED have very similar grades to those who complete high school, the salary earnings of those who take the GED look very similar to regular dropouts, meaning that GED attainment has little value in terms of future earnings. The data therefore seems to suggest that taking the GED instead of staying in high school does not have an economic benefit.

GED recipients tend to have lower success rates later in life, which could be attributed to a lack of non-cognitive skills. Heckman and his co-authors also found that “the marginal benefit of increasing non-cognitive ability for GEDs, especially in the bottom two deciles, is greater than the marginal benefit of increasing a decile of cognitive ability.”[56] In other words, non-cognitive ability goes further in terms of educational attainment than cognitive ability. So the GED seems to serve as an outlet for students who find themselves frustrated with school or want a quicker way out of high school, and these tend to be students who have not developed the non-cognitive skills needed to complement the cognitive skills that lead so success. Only 31 percent of GED recipients enrolled in college, of which 77 percent attended only there for a semester. Heckman found that 31.7 percent of high school graduates completed a four-year degree, compared to 6 percent of GED recipients.[57] It appears that students who take the GED do so in large part because they find themselves frustrated with education, so it is not surprising that they become frustrated with college

Moreover, GED acquisition distorts high school graduation data, making it appear as if U.S. graduation rates have improved over recent years. Heckman found that “removing GEDs lowers overall graduation rates by 7.4%...8.1% for males, 6.6% for females, 10.3% for black males, and 8.7% for black females.”[58] Even more troubling, Heckman warns that many GED credentials even have misleading names, which further distorts the data: “Many state-issued GED certificates have names such as Kansas State High School Diploma or Maryland High School Diploma which misleads students into false expectations of equivalence with traditional high school.”[59] If the goal is to improve high school graduation rates, schools must have a very clear idea of what the data are showing. As long as the GED distorts graduation rates, improvements in education will be difficult to measure.

The GED, then, has become a credential that provides little help for future economic mobility and may exacerbate the problem of low non-cognitive skills by offering would-be graduates an incentive to drop out of high school. It does not seem, in reality, to provide a true second chance or alternative option. Students who drop out and then take the GED may not have the time or motivation to develop the non-cognitive skills for success that should come with a high school diploma. States and local school authorities should focus on the non-cognitive traits that dropouts and GED recipients share, and develop methods for keeping teens in high school instead of dropping out due to frustration.

What Can Be Done?

Given the research, it seems clear that keeping teenagers in high school until graduation starts with character development. Schools must gear their energies toward determining how best to develop the non-cognitive skills associated with success in school and beyond. In How Children Succeed, Paul Tough discusses the character traits associated with children who succeed in school and those who do not, and he gives examples of strategies that build these traits. Too often, unfortunately, the presumption is that academic failures are solely linked to intelligence. Like other analysts, Tough argues that there are many character traits, such as persistence and grit, that are far greater indicators of success than intelligence. Character education, or the idea that schools should foster a child’s non-cognitive skills to promote the education of the “whole person,” is a growing trend in school across the United States. To be sure, character education can be done well and it can be done badly. But research by Angela Duckworth, supporting Tough and others, found that “self-discipline predicted academic performance more robustly than did IQ. Self-discipline also predicted which students would improve their grades over the course of the school year, whereas IQ did not.”[60]

Which approaches may enhance the development of these critical skills and the likelihood of high school graduation? Several approaches look promising.

School Choice. Perhaps the best way to address the problem is to give parents real choice over which school to send their children. School choice is rapidly expanding all over the country. If students are able to attend high-quality public schools or charter schools, regardless of where they live, factors that contribute to the achievement gap such as race or income will start to diminish. Different children thrive in different environments and in different academic areas. School choice gives parents the freedom to match their children to the school that best fits their particular talents and needs. When students are in an environment of their or their parents’ choosing they have more motivation to succeed.

The research seems to support such benefits of choice. A National Bureau of Economic Research study, for instance, found that “winning the lottery to attend a chosen school has an immediate impact on absences and suspensions after notification, and that this result is particularly strong for older male students.”[61] School choice has positive effects on motivation and school performance. The U.S. Department of Education found that simply receiving a scholarship to attend a school of choice increased graduation rates by about 12 percent.[62] These children are doing better in school, and parents reported feeling that their children are in a safer environment. The Education Department’s evaluation revealed, “School safety is a valued feature of schools for the families who applied to the Opportunity Scholarship Program. A total of 17 percent of cohort 1 parents at baseline listed school safety as their most important reason for seeking to exercise school choice—second only to academic quality (48 percent) among the available reason.”[63] (Cohort 1 parents were those who opted for school choice. They found themselves significantly more satisfied with their children’s educational environment than parents who did not choose their children’s school.) The increase in graduation rates alone shows that giving parents a voice in how and where their children receive an education can significantly improve academic outcomes.

Community Schools. Schools have an interesting ability to serve as a cultural and economic center of a neighborhood that may previously have lacked any form of social infrastructure. Community schools build on that ability and add a variety of support services, traditionally unrelated to education, into the academic context.[64] Schools typically collaborate with other institutions, such as health clinics or counseling centers, to create a center of services that is open to the community. The Briya Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., for example, collaborates with Mary’s Center. Mary’s Center provides health services, family literacy classes, and social services in the same building; these services are also available to their surrounding community—including to another charter school and a public school in the neighborhood. Mary’s Center’s presence at the Briya Charter School has significantly impacted the lives of the families they serve. The Briya Charter School is for children up to age five, and Mary’s Center has special programs for teenagers and young adults. This location therefore provides services for a wide range of community members. Ninety percent of teenagers who participate in Mary’s Center programs graduate from high school, and 72 percent attend college.[65] It turns out that an important level of trust and cooperation forms among members of a community when there is a common place where everyone goes for assistance, and where services are integrated. Mary’s Center builds on the social capital and resources provided by Briya and helps to move the neighborhood toward economic stability. If this model is carefully replicated with the specific needs of low-income communities in mind, community schools can significantly impact high school graduation rates.

Dropout Prevention Programs. Some schools across the country are, however, departing from an obsession over IQ and instead focusing their efforts on drug control, violence prevention, and character development, among other things. The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) studied various programs across the country[66] that target at-risk youth and help keep them in school. Here are a few examples:

- The National Guard Youth Challenge Program. The WWC examined whether the National Guard Challenge program improved both the character and educational outcomes of at-risk youth. This program is a 22-week military-style arrangement where students live together in “barracks,” followed by a year of mentoring. These students were subject to military-level discipline. The study found that the Challenge Program increased the percentage of youth who had earned a high school diploma by 46 percent compared to 10 percent for the control group.[67] The character building that took place during the National Guard Youth Challenge Program gave students the skills and motivation to value their education and pursue a degree.

- High school vocational programs that target male completion. Programs focused around a specific career often give students a feeling of direction and purpose that encourages them to stay in school. The WWC recommends that schools “[i]ntegrate academic content with career and skills-based themes through career academies or multiple pathways models. Students should have the opportunity to see the relevance of their academic work by applying academic skills to work-world problems.”[68]

- Violence-Free Zones. Robert Woodson, president of the Center for Neighborhood Enterprise, addressed the problem of school violence head on with the creation of Violence-Free Zones (VFZs). Woodson, like many others, realized that children cannot succeed in school if they are constantly faced with the stress of a hostile environment. The Center for Neighborhood Enterprise collaborates with local community leaders to institute VFZs in high schools that are plagued with violence. The Violence-Free Zone initiative turned students who were previously deemed troublemakers into what Woodson calls, “ambassadors of peace.” These teenagers can offer positive pressure to their peers and spread a positive environment through high schools across America. The Violence Free Zones have helped students all across the country gain a meaningful education without the stress of safety concerns. The Center for Neighborhood Enterprise found, “In the first two years in Dallas, where the VFZ was first piloted, gang incidents were reduced from 113 to 0.” Similarly, the VFZ initiative in Richmond, Virginia, yielded remarkable results. Richmond police reported that “[a]rrests of students at the school were down 38%, and incidents reported by the police School Resource Officer were down 46%.”[69] Through a combination of oversight by youth mentors and program directors, students are given the guidance and motivation to peacefully learn with other students.

Conclusion

Dropping out of high school severely limits the ability to move up the economic ladder and achieve success later in life. Many of today’s schools are not properly geared toward developing non-cognitive skills, such as perseverance, grit, motivation, and organization, which enable children to finish high school and achieve their goals. Minority, low-income, and male students are hit the hardest by the barriers to high school completion.

Administrators and policymakers should focus on strategies that develop the broad range of skills needed for success, thereby developing the whole person. This approach begins with targeting violence, drug use, and other negative community influences that encourage students to drop out rather than make responsible decisions for their future. Several successful programs have been implemented at various high schools around the country. Schools should look within themselves, identify the specific barriers to high school completion that plague their community, and design programs that target the needs of their at-risk youth. Policymakers should foster experimentation to find better strategies, and they should make it much easier for parents to select schools that match the needs of their children.

Education is arguably the most crucial factor that contributes to a child’s ability to move up the economic ladder. For many young Americans, the decision of whether or not to complete high school is the first significant choice they will make in life and it will decisively influence their future. Encouraging students to acquire the skills needed to make the right decision is crucial for their chances of upward mobility.

—Mary Clare Reim is a Research Assistant in the Center for Policy Innovation at The Heritage Foundation.