A president who never held elected office before occupying the White House faces plenty of enemies, even some skepticism among fellow Republicans and no shortage of investigations during his time in power. Who would guess that when he gets charged, it’s by local law enforcement for what seems like a petty matter?

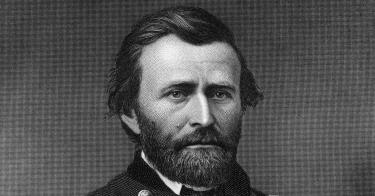

It was 1872 when Washington police officer William H. West stopped President Ulysses S. Grant for speeding in his horse-drawn carriage down the streets of the nation’s capital.

Grant holds the distinction of being the only president ever arrested—even if it was just for speeding. Other presidents and presidential candidates have found themselves in legal jeopardy as well.

Former president Richard Nixon would have faced a likely indictment from Watergate prosecutors had it not been for a pardon from his successor, Gerald Ford. Former president Bill Clinton came even closer to an indictment in the form of an eleventh-hour deal reached with federal prosecutors before leaving office.

In both these cases, the pardon and the deal were struck in the name of helping the country move on. In the case of Trump, the former president is now a candidate for president. Not only that, but at least before Alvin Bragg announced last week that he was indicting him, Trump was neck-and-neck in the polls with President Joe Biden and comfortably leading all other GOP contenders. The prospect of moving on doesn’t apply as much here.

>>> Unsealed Trump Indictment Previews a Case That Puts Us in Uncharted Territory

Trump is certainly not the only candidate for president to ever face criminal prosecution. Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs won almost 1 million votes in the 1920 election from a prison cell, serving a sentence under a Woodrow Wilson-era sedition law for opposing America’s involvement in World War One.

Justice Department policy states, “The indictment or criminal prosecution of a sitting President would unconstitutionally undermine the capacity of the executive branch to perform its constitutionally assigned functions.” This wouldn’t affect the prosecution of a former president, however, nor would it even prevent a local prosecutor from bringing charges against a sitting president. The Manhattan grand jury has quite likely cracked open the door to bigger things in the future.

While it seems almost absurd to say, it’s the Grant arrest for speeding that comes closest to Trump’s indictment for allegedly paying hush money to porn star Stormy Daniels.

There are plenty of differences between the two cases, of course. A big one is that West didn’t set out to arrest Grant. It was a chance encounter and he even felt sorrow—though nevertheless dutybound—when he did so.

By contrast, Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg campaigned on nabbing Trump, for something…anything. It’s also highly unlikely that anyone other than Trump would have been charged under what we’re consistently told is a “novel legal theory.”

Another clear difference is that Bragg, an elected Democrat, has every political motivation to prosecute Trump. Whereas West, the DC police officer, was a black former veteran of the Union Army in the Civil War, giving him every reason to support Grant’s policies.

Another somewhat astonishing difference is that the Grant arrest was kept mostly under wraps until West told the full story to the Washington Evening Star newspaper in 1908.

Again, it was a minor offense, but Grant was up for re-election in 1872. Had it been known at the time, surely his erratic opponent, Horace Greeley, would have made it into an issue—and the New York Tribune, which Greeley edited, would have turned it into a national scandal.

In 1872, the Washington police were getting complaints about speeding carriages, which they sent West to investigate. While there, he saw speeding carriages, one of them carrying the president. “Policeman West held up his hand for them to stop,” the Star story reported.

West told the president: “I want to inform you, Mr. President, that you are violating the law by speeding along this street. Your fast driving, sir, has set the example for a lot of other gentlemen.”

Grant promised not to do it again, which is what we all say when pulled over.

The next day, on the same city block, 13th and M Streets in Washington, West again stopped the president. The Star story said Grant was smiling like “a schoolboy who had been caught in a guilty act by his teacher,” and asked, “Do you think, officer, that I was violating the speed laws?”

West told him, “I am very sorry, Mr. President, to have to do it, for you are the chief of the nation, and I am nothing but a policeman, but duty is duty, sir, and I will have to place you under arrest.”

According to the Star’s story, Grant “admired a man who did his duty,” willingly went to the police station, and chatted with West about his wartime experience. But the six men riding with Grant, some of whom were reportedly high-ranking government officials, didn’t take the episode nearly so well.

>>> Inside the Minds of Trump’s Lawyers—How the Defense Will Unfold

Grant paid $20 in collateral, which he lost by not showing up in court the following day. The other six contested their case and attacked West for “outrageous conduct… in daring to arrest gentlemen out for a pleasant drive.”

One can imagine how the arrests and the spectacle Grant’s friends made of themselves would play on cable news today, with angry pundits leaping into polarized corners. As it turned out, they lost their case.

Should Trump be convicted in the Manhattan case or any other of the investigations happening, there is nothing that would stop him from continuing his campaign for president.

Possibly the nation’s worst president, Woodrow Wilson, signed the Sedition Act of 1918 during World War One, which criminalized speech deemed to be disloyal to the United States government. The most high-profile person convicted was Debs, a perennial presidential candidate for the Socialist Party since 1900. He was sentenced to ten years in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, but that didn’t stop him from running for president in 1920 and winning 919,799 votes—or 3.4 percent of the popular vote—from behind bars. Wilson’s successor, Warren G. Harding, gave a Christmas commutation to Debs in 1921.

It seems likely that if Bragg could have nailed Trump for disloyal speech, or even speeding in his stretch limo, he would have. A sex scandal will have to do for now.

Yet far more so than in the cases of Grant and Debs, the proverbial glass has been broken. We should expect to see similar charges in the future from local prosecutors looking to make a national name for themselves—even if it means more creative novel legal theories. Trump isn’t the first president to face legal scrutiny, but his indictment is still unprecedented.

This piece originally appeared in The Spectator