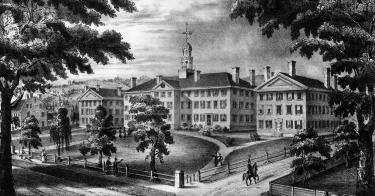

Jeff Clements, author of “Corporations Are Not People,” delivered a lecture of the same title at Dartmouth a few years ago. One wonders if Mr. Clements appreciated the irony. It was in Dartmouth College v. Woodward, decided Feb. 2, 1819, that the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the legal personhood of corporations as an essential principle of American law.

In a decision by Chief Justice John Marshall, the court saved the school from the state of New Hampshire’s hostile takeover. According to Marshall, the court was duty-bound to defend the college’s independence because its corporate charter was protected by the Constitution’s prohibition on state laws “impairing the obligation of contracts.” Dartmouth as an institution—not the teachers, trustees or students, but the corporation itself—had rights the court was obliged to uphold.

Although he did not use the exact words, Marshall clearly affirmed the principle that corporations are legal persons. “A corporation,” he explained, “is an artificial being” existing “in contemplation of law” and possessing a certain “individuality.” Its legal existence necessarily entailed its possession of some rights that are also held by “natural persons,” such as a right to hold and transmit property and a right to sue in the courts in defense of its other rights.

Corporations are essential to a free society. As Marshall observed, Dartmouth was founded not as an arm of the state but as a private charitable institution of the sort that “do not fill the place that would otherwise be occupied by government, but that which would otherwise remain vacant.” Such institutions, however, could not function effectively without the right, bestowed by a corporation’s legal personhood, to “manage” their own affairs and “to hold property” and dispose of it in the pursuit of their missions.

In other words, Marshall—and the founding generation with him—envisioned a country in which much of the good work done on behalf of society is done not by government but by individuals uniting their efforts through legally recognized but private organizations. They emphatically did not envision a society in which government asserts power over everything and nothing gets done without state or federal intervention. Among the lessons of the 20th century is that this American vision is much to be preferred to the statist alternative.

All of us—even those who loudly insist that “corporations are not people!”—have benefited immensely from the legal personhood and rights of corporations. The 200th anniversary of Marshall’s wise Dartmouth College opinion is a good occasion to remember that.

This piece originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal