As they celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next year, many Americans will remember fondly the patriotism and pageantry of the 1976 bicentennial. Few people were even aware of the bicentennial of 1987, the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Constitution.

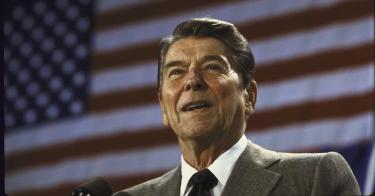

Yet by the end of President Reagan’s administration, the originalist revolution was underway. Indeed, with the benefit of hindsight, the preceding three years changed the course of the Constitution.

First, in 1985, Attorney General Edwin Meese III battled Justice William J. Brennan in a public debate about originalism. Second, in 1986, Reagan, after Meese’s advice, elevated William H. Rehnquist to chief justice and nominated Antonin Scalia to the high court. Third, in 1987, though Judge Robert Bork’s nomination was unfairly blocked, his unapologetic embrace of originalism set the template for future nominees.

The Roberts court turns 20 this year, but we should proudly celebrate the fourth decade of the originalist revolution.

>>> How “Originalism” Became the Prevailing View at the U.S. Supreme Court

When the Declaration of Independence turned 200, constitutional law was in sorry shape. The Warren E. Burger court had just created a right to abortion in Roe v. Wade (1973). Nearly two decades of the Earl Warren court had manufactured out of whole cloth invented dangerous rules of criminal procedure while intervening in nearly every facet of the democratic process. Earlier, the New Deal court vastly expanded the federal government’s powers while radically altering the separation of powers.

It would have been easy to despair at the start of Reagan’s first term, but a constitutional cavalry was on the way.

In July 1985, Mr. Meese fired the shot heard ’round the world. At a meeting of the American Bar Association, he announced that the Department of Justice would “endeavor to resurrect the original meaning of constitutional provisions and statutes as the only reliable guide for judgment.” This speech was the Lexington and Concord for the originalist revolution.

Justice Brennan, the liberal line of the Supreme Court, charged back that originalism was “little more than arrogance cloaked as humility.” In time, Brennan’s activism would be seen as the apex of judicial arrogance. Today, no one on the Supreme Court would publicly reject originalism. Indeed, the liberals at least profess partial fidelity to original meaning.

For more than a decade before becoming chief justice in 1986, Rehnquist had served as the court’s leading, and at times only, originalist. He called on the court to revisit its decisions concerning the separation of powers and rejected the invention of liberal rights. Nominating Scalia to the Supreme Court was also a fateful decision. A former law professor, Scalia would bring the perfect blend of intellect, dedication and charisma to the job.

Over time, Rehnquist became the leader of the federalism revolution, restoring the line between the powers of the national and local governments. Scalia became a constitutional evangelist, writing memorable opinions that were studied by law students. He traveled the country to speak directly to the next generation.

At the time, 1987 may have seemed like a bad year for originalism. Reagan nominated one of the original architects of originalism, Bork, to the Supreme Court. His 1971 article on free speech was one of the first careful studies of how to apply the history behind the First Amendment.

>>>

Bork was unfairly attacked and maligned by Democrats, and his nomination failed, but with the benefit of hindsight, what was perhaps most important about his hearing is that the former law professor was an unapologetic originalist. He didn’t parrot the modern orthodoxy about living constitutionalism. Bork was punished for his honesty and denied a seat on the court, but he set the template for future Supreme Court nominations.

Even as Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. declined to say he was an originalist, all three of President Trump’s nominees proudly embraced originalism. Indeed, even Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said she was an originalist during her confirmation hearing. This turn of events would have been unthinkable in 1987 but would not have been possible without Bork’s candor and fidelity to the Constitution.

As the court continues to decide cases consistent with original meaning and reject precedents made up by legal activists in robes, we should be thankful for the wisdom of these four jurists. In the new edition of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution, which we co-edited, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote, “If we can envision a Mt. Rushmore of originalism, the three visages we would see carved in stone are those of Robert Bork, Edwin Meese III and Antonin Scalia.”

We would respectfully add one more visage to the mountain: Rehnquist. In the mere span of three years, these four individuals set the Constitution on a course correction. In 2037, on the Constitution’s 250th anniversary, there will be a lot more to celebrate.

This piece originally appeared in The Washington Times