Introduction

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled against the use of racial preferences in college admissions, delivering a long-awaited opinion supporting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and upholding the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The decisions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina are necessary, although insufficient, steps for reversing decades of discrimination exercised by college and university administrators who used racial preferences in their admissions decisions. Policy changes will be needed to implement the decision because college administrators have ignored or circumvented laws such as Proposition 209 in California that abolished racial preferences in college admissions and hiring decisions, and because the nation needs clarity on more promising approaches to address the disparities that led to such unfair and discriminatory racial preferences in the first place.

This Special Report documents:

- How racial preferences work in practice;

- The decisions handed down by the Supreme Court in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina;

- The history of racial preferences in federal policy, beginning with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Administration and the history and policies demonstrating that racial and ethnic preferences fail all Americans, including minorities;

- The history of “mismatch” research, a field of study almost as old as the practice of racial preferences in college admissions, and one that has gained significant attention from national civil rights leaders, such as the members of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights;

- How colleges have tried to circumvent the prohibition of racial preferences in the past and how they might continue to try to do so;

- What defines equal opportunity, how can it be measured, and the role that family structure plays in a child’s education;

- Potential criticism of policy recommendations that reject racial preferences; and

- Recommendations for state and federal lawmakers to follow through on the Court’s opinion.

Racial Preferences in Practice

Many Americans may not realize how racial preferences are used in admissions and that they often involve what college admissions officers call “academic index” scores. Although minority racial preferences in college admissions date back at least as far as the early 1960s, college administrators began using academic index scores in the 1980s. A student’s academic index is the numerical score that a college calculates based on an applicant’s grade point average (GPA), college admissions tests, such as the SAT or ACT, and other academic elements, such as class rank. Not every school uses an academic index, and schools calculate the index in different ways, but the practice is not uncommon.

Through the use of academic index scores, officials can award additional points to some minority students, though, as the Students for Fair Admissions cases described below indicate, not all applicants from ethnic or racial minority groups benefit from racial preferences in admissions. But for those who do, college officials sometimes calculate these additional points based on the average numerical difference in academic index scores between minority students and their peers.REF

Today, many colleges—including Ivy League institutions—assign student applicants more than just an academic index score when considering the applicant for admission.REF They add criteria for personality characteristics that suggest whether the applicant will fit in and succeed at the institution.

Researchers have documented achievement gaps in K–12 schools between black students and their non-black peers for decades, along with gaps between students from lower-income families and their peers from middle-income and upper-income homes.REF Proponents of racial preferences, and adherents of the discipline of critical race theory, contend that these disparities are prima facie evidence of the existence of “institutional racism,”REF but in reality these gaps have causes better explained by particular historical and cultural factors than by any present systemic bias.

One may consider, for instance, the effects of family formation. Family intactness is closely correlated to good life outcomes. Nigerian-Americans have rates of family intactness that are nearly equal to that of whites, and their disparities with whites on several cultural indicators are negligible.REF Indeed, at least one study shows that 73.5 percent of U.S.-born Nigerian Americans are college graduates, compared to 32.9 percent of U.S. whites, laying waste to the “systemic racism” explanation for racial disparities, and showing once again the strong impact of family intactness on success. These data also demonstrate the need to move beyond the current monolithic Census racial categories.REF This Special Report discusses the subject of “equal opportunities,” what this term means, and how racial preferences fail to equalize opportunities for black Americans—and all Americans.

Socioeconomic disparities are not present between every white student and every black student. Rather, they manifest themselves in averages. The very calculation of such averages has resulted in black students being treated as a group instead of as individuals with unique needs and abilities just like every other young adult applying to college. According to researcher Richard Sander, policies that apply racial preferences based on the idea that all black students need such help “insulate the black applicants from direct competition” with their peers,REF which is ultimately detrimental to everyone’s development.

And yet, by 1980, more than 75 percent of black students who were accepted at selective colleges received a racial preference.REF These policies rob young people of the opportunity to be judged on their own merits. Not surprisingly, surveys find that most Americans consistently oppose the use of racial preferences in admissions. A Pew Research survey from June 2023 found that 82 percent of adults believe that college officials should not consider race or ethnicity in admissions decisions.REF This is consistent with prior polling: In 2019, Pew Research found that 73 percent of respondents said that colleges should not consider race in admissions.REF

Notably, nearly two-thirds of black respondents agreed, with 62 percent opposing racial preferences. Sixty-three percent of registered Democrats or respondents who leaned Democratic opposed the idea. Sixty-seven percent of total respondents said that high school grades should be the top factor in admissions decisions, making grades the most popular response to the question of what should be the most important factor in college admissions.

This latter figure was only slightly reduced in 2022, to 61 percent, but grades were still the most popular factor among respondents.REF Fifty-nine percent of black respondents said that race should not be a factor, close to the 2019 figure. Sixty-eight percent of Hispanic respondents said that race should not be a factor.

Not only do institutions that use racial preferences treat certain students as inferior based on the color of their skin, and not only is the practice highly unpopular, but racial preferences create a “mismatch” between students and schools.REF According to the research of Richard Sander and others, black students are one-third more likely than white students with similar academic and personal characteristics to start college.REF Yet black students are less likely than their white peers with similar characteristics to finish.

As we explain in this Special Report, the primary reason for this disparity is because academically selective schools leverage racial preferences to admit students who have not been prepared by their K–12 schools to succeed in such institutions. Academically high-achieving black students do enter selective colleges and universities and often perform exceptionally well—and these students demonstrate the requisite aptitude and academic preparation in their applications and thus do not need preferences for admission. Research finds, however, that students who are admitted after being awarded additional points on their academic index often struggle mightily and are unable to complete their course of study.

As Sander explains, “Students who have much lower academic preparation than their classmates will not only learn less than those around them, but less than they would have learned in an environment where the academic index gap was smaller or did not exist.”REF

Racial preferences, then, result in a mismatch, which results in students failing in school, leading to less learning and, ultimately, worse outcomes in the job market. For example, research has demonstrated that black students admitted to law school using racial preferences perform worse on the bar exam, resulting in far fewer opportunities after they graduate.REF This can present additional financial difficulties for those students who borrowed money to finance college or graduate school, only to find themselves struggling to repay their loans. That is one reason why Congress should require colleges to assume financial responsibility for a portion of student loan defaults.

The Harvard/UNC Litigation and the History of Discriminatory Admissions Policies

In two separate lawsuits, Students for Fair Admissions (SFA) sued the University of North Carolina (UNC) and Harvard University on behalf of Asian American college applicants—themselves members of a minority ethnicity in the United States. SFA claimed that the biased admissions policies of both universities, two of the oldest public and private universities in the nation, discriminated against Asian-American students and violated both the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. SFA says: “It turns out that the suspicions of Asian-American alumni, students, and applicants were right all along: Harvard today engages in the same kind of discrimination and stereotyping that it used to justify quotas on Jewish applicants in the 1920’s and 1930’s.”REF

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides that states may not “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Section 601 of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act states: “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”REF

Since both universities receive federal funds either directly or indirectly through grants and student loans, there is no question that this provision of Title VI applies to them. It is also undisputed that both universities give racial preferences to African American, Hispanic, and Native American applicants, such that they are often admitted despite having lower test scores and lower grade point averages than otherwise comparable white or Asian American applicants. However, the universities claimed this was an acceptable practice under applicable court precedent and necessary to achieve a diverse student body. What made the difference at Harvard was the use of subjective personality scores, which were lower for Asian American applicants. But as President John F. Kennedy said in 1963, “Simple justice requires that public funds, to which all taxpayers of all races [colors, and national origins] contribute, not be spent in any fashion which encourages, entrenches, subsidizes or results in racial [color or national origin] discrimination.”REF

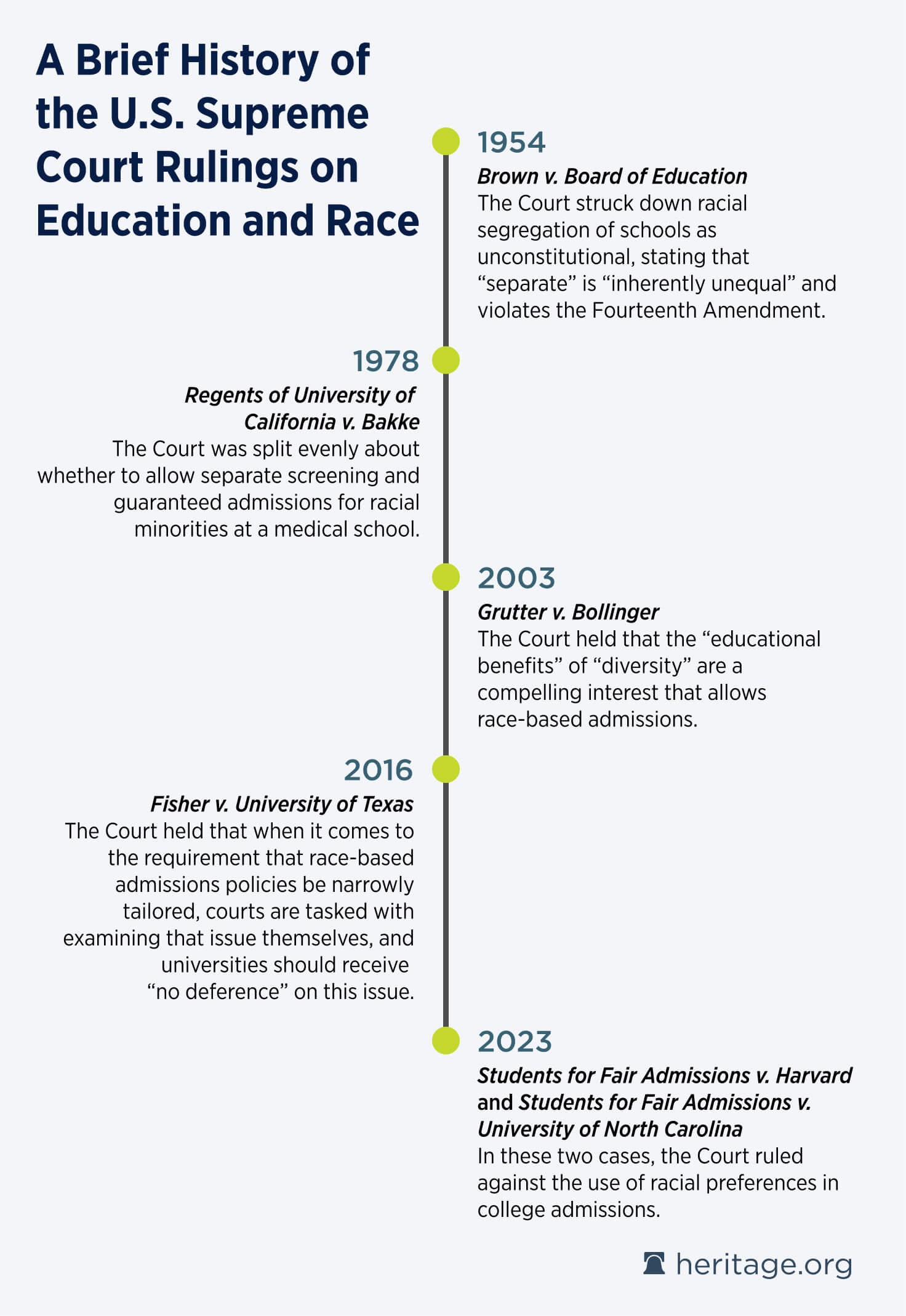

The applicable precedent to these cases brought by SFA representing Asian American students was a series of decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court on the use of race in college admissions. In the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education,REF the Supreme Court overruled its 1896 decision in Plessy v. FergusonREF that had declared that segregated public schools were constitutional as long as they were “separate but equal.” Separate is “inherently unequal” and violated the Fourteenth Amendment said the Court in Brown, the decision that led to the desegregation of the nation’s public schools during the civil rights era.REF That decision led to “massive resistance” from state officials, schools, and universities, led in part by Democratic Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, who organized a coalition “of nearly 100 Southern politicians to sign on to his ‘Southern Manifesto,’ [an] agreement to resist the implementation of Brown.”REF

A series of cases over the use of race in college admissions, including Regents of University of California v. Bakke,REF finally led to the Supreme Court’s decision in Grutter v. BollingerREF in 2003. In Grutter, the Court held that the “educational benefits” of “diversity” are a compelling interest that allows race-based admissions,REF a holding that was just as wrong from a constitutional standpoint under the Equal Protection Clause as the Plessy decision was in 1896.

To meet the compelling-interest standard under strict scrutiny that would allow a public university to consider race, the Court in Grutter said that a university must show that its admissions policy is narrowly tailored to achieve the educational benefits of racial diversity: It can be a “plus” factor but cannot be an application’s “defining feature.”REF Additionally, universities must consider race-neutral alternatives in good faith and diversity-oriented admissions policies should be “limited in time.”REF

In another college admissions case decided in 2016, Fisher v. University of Texas, involving the University of Texas at Austin, the Supreme Court held that when it came to the requirement that race-based admissions policies be narrowly tailored, courts were tasked with examining that issue themselves and universities should be given “no deference” on this issue.REF The Court specifically noted that none of the parties in that case had asked it to reconsider the Grutter decision (that there is a compelling interest in racial preferences in higher education).REF

Despite what the Court said in Fisher, it seems clear that many universities, such as Harvard and UNC, have given only token acknowledgement over the past two decades to the “narrowly tailored” and “race-neutral alternatives” requirements and instead have engaged in wholesale discrimination on the basis of race in their admissions. And the lower courts have gone along with it.

The durational limit in Grutter for university policies led to the well-known words from the majority opinion written by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor that the Court expected that “25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.”REF Justice Anthony Kennedy said in his dissent in Grutter that this was the first time that the Supreme Court had set a constitutional precedent with “its own self-destruct mechanism.”REF

Fortunately, that self-destruct mechanism has apparently finally been triggered with the Supreme Court’s decision in the Harvard/UNC case. On June 29, 2023, a majority of the Court in an opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts concluded that the race-based admissions policies of both universities violate the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.REF The Court noted that the admissions process at both universities unlawfully incorporates an applicant’s race throughout and for many applicants “race is a determinative” factor.REF

After going through an extensive history of the Court’s precedents under the Fourteenth Amendment, including its “ignoble history” of allowing the “separate but equal doctrine” of the Plessy decision to “deface much of America,”REF Roberts then proceeded to demolish all of the claims made by the universities to justify their racial discrimination, stating that “[e]liminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.”REF

Roberts pointed out that the Court has permitted race-based admissions only within the confines of very narrow restrictions as outlined in its precedents, including Grutter and Fisher. “University programs,” said Roberts, “must comply with strict scrutiny, they may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and—at some point—they must end.” The discriminatory admissions policies of Harvard and UNC “fail each of these criteria.”REF

Robert’s majority opinion concludes that none of the supposedly compelling goals of discriminating in admissions proffered by Harvard and UNC could be “subjected to meaningful judicial review.” The benefits, said the universities, include “training future leaders,” “promoting robust exchange of ideas,” “producing new knowledge stemming from diverse outlooks,” and “preparing engaged and productive citizens and leaders.” While commendable goals, “they are not sufficiently coherent” to meet the demands of strict scrutiny, and it is unclear how courts “are supposed to measure any of these goals.” Even if they could be measured, “how is a court to know when they have been reached, and when the perilous remedy of racial preferences may cease?”REF

Second, the universities failed to show a connection between the discriminatory means they employ in admissions and their goal of diversity. They use racial categories to measure the racial composition of their classes that in some instances are overbroad (such as not distinguishing between South Asian or East Asian students), arbitrary or undefined (Hispanic), or underinclusive (no category for Middle Eastern students). The universities’ response to this criticism was “trust us,” but the Court held that deference to their decisions must exist within constitutional limits, and the schools have failed to justify separating students on the basis of race.REF

The Court also held that these admissions policies fail the Equal Protection Clause’s twin commands that race may never be used as a “negative” and that it may not operate as a stereotype. But the evidence showed that the colleges’ assertion that race is never a negative factor “cannot withstand scrutiny” given the decrease in the admission of Asian-American students due to these policies. Moreover, the claim that the admissions policies achieve diversity of thought and viewpoint were based on the “offensive and demeaning assumption that [students] of a particular race, because of their race, think alike.”REF

The universities offered no “logical end point” to their racial discrimination. They argued that their use of race will end when there is meaningful representation and diversity on college campuses, based on comparing the student population to “proportional representation” in the general population, but the Court rejected this argument because such racial balancing is “patently unconstitutional.” They also claimed they periodically review their programs to see if they are still needed, but the Court rejected that justification as well, saying that periodic review cannot make “unconstitutional conduct constitutional.” And both universities admitted that their race-based admission policies were “not set to expire any time soon—nor, indeed any time at all.”REF

The majority opinion concludes that:

[T]he Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and will not do so today.REF

The majority opinion did add one proviso about how race can still be indirectly considered in a limited way in the admissions process, seemingly setting up what the topic will be in the future in the essays that many colleges require from students applying for admission. Universities can consider an “applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” However, consideration of that discussion “must be tied to that student’s courage and determination,” or “that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university.” In other words, said Roberts, “the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.”REF

In a scathingly accurate assessment of college administrators everywhere in the final paragraph of the majority opinion, the Court said that ”universities have for too long” not treated students as individuals, but have “concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.”REF

It should be noted that while the majority opinion threw out the Harvard and UNC admissions policies based on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, it explained in a footnote that the Court has previously held that any discrimination that violates the Equal Protection Clause committed by an institution that accepts federal funds also constitutes a violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Justice Neil Gorsuch in his concurrence, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, emphasized that point.

Now that the Court has removed the corner-cutting strategy of racial preferences, which clumsily tried to manage outcomes rather than grapple with the underlying causes of disparity, policymakers can finally approach the matter of family formation. This was the approach intended by one leading Johnson Administration official, Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Policymakers must also try to make it impossible, or as difficult as possible, for university officials to continue, through concealed ways, to discriminate by race through the use of racial preferences in admissions policies.

The Birth of Racial Preferences: How Civil Rights and Social Justice Descended into Racial Preferences

On June 4, 1965, barely 11 months after signing into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson gave the commencement address to the graduating class of Howard University that has become famous for heralding the advent of his Great Society. In the remarks, which he gave before an enormous crowd of 14,000 people and is known to history as the “To Fulfill These Rights” speech (an echo of the Declaration of Independence), Johnson rightly celebrated the fact that the United States had finally put legal and legally mandated segregation behind it.

“We have seen the high court of the country declare that discrimination based on race was repugnant to the Constitution, and therefore void,”REF said Johnson, who had every right to sound triumphant. He had just been elected in a landslide win over Barry Goldwater, and his party had catapulted Democratic candidates to large majorities in the Senate and the House of Representatives. Moreover, the country had become convinced that government had to protect the rights of all American citizens.

That American government at all levels was finally pledging color-blind justice was indeed an achievement and was at the heart of the pledges made by those who promoted civil rights. The phrase “affirmative action,” as contained in one of the first executive orders that President John F. Kennedy signed upon taking office in 1961, promised color-blindness in government contracting: “The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.”REF (Emphasis added.)

Indeed, in his 1963 speech on civil rights, President Kennedy went out of his way to convince the country, parts of which remained wary of racial equality, that color-blindness was going to be the law of the land, as the Constitution dictates. “It ought to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color,” said Kennedy.REF

With that in mind, and in order to address concerns that the Civil Rights Act would turn into a racial spoils system, Minnesota Democratic Senator Hubert Humphrey promised on the floor of the Senate in a 1964 debate that if a “Senator can find…any language which provides that an employer will have to hire on the basis of percentage or quota related to color, race, religion, or national origin, I will start eating the pages one after another, because it is not in there.”REF Humphrey was not just any Senator. By the time President Johnson spoke to the Howard graduates, Humphrey was already his Vice President.

But President Johnson did not just celebrate the fact that government, federal or state, would henceforth observe the constitutional rights of black Americans, a monumental advance. He also attempted to advance two other shifts that were in themselves historic. One, ironically, was to reintroduce the idea that race could now be used again as a cause for government intervention. The speech at Howard, in effect, is known for that, and therefore as the starting point of interpreting affirmative action to ensure racial preferences in employment and school admissions.

Almost always ignored, however, is the second shift the speech heralded. The main speechwriter, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, intended to use racial preferences for something new in America: family policy. The sagacious Moynihan had understood that trouble was brewing within the black family, especially in impoverished black urban areas in the North, and that this was at the heart of widening racial disparities. He wanted the government to address family breakdown.

It is the tragedy of the past 60 years that only racial preferences stuck: Government and the private sector began to react to academic and economic achievement gaps by trying to force particular outcomes, reinforcing the message that black Americans were not ultimately responsible for their own welfare. However, the men surrounding Johnson, and those in the commentariat, dropped the matter of the breakdown of the black family—Moynihan’s main point—as a main cause of the disparities.

Racial Preferences v. Needs-Based Policy. President Johnson did, indeed, reverse course just a few seconds after declaring that racial discrimination was repugnant to the Constitution:

But freedom is not enough. You do not wipe away the scars of centuries by saying: Now you are free to go where you want, and do as you desire, and choose the leaders you please. You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, “you are free to compete with all the others,” and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.REF

It was this statement that, as The Washington Post put it when it marked the half-century anniversary of Johnson’s appearance in 2015, made the “To Fulfill These Rights” speech “widely known as the intellectual framework for affirmative action.”REF

This indication from the highest government official in the land that fairness required a return to the same type of racial discrimination that he had just declared repugnant to the Constitution helped to turn the course of history. It made clear to all that Johnson was now authorizing, encouraging, and even requiring that employers hire and treat employees with regard to their race, color, and national origin. This violated everything that had been promised. But by the time the Supreme Court codified the use of race in university admissions, in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke on June 26, 1978, Humphrey had been dead six months and was not able to answer for his promise that the Civil Rights Act would not be used to impose racial quotas.

President Johnson was not the first to use the unequal race analogy. Moynihan—a wunderkind who had been Kennedy’s Assistant Secretary of Labor, would later advise President Richard Nixon and then become a U.S. Senator. The speech’s other drafter, White House speechwriter Richard Goodwin, surely must have known that Herbert Croly had introduced the race analogy decades earlier. One of the intellectual leaders of the progressive era, Croly had famously employed it in 1909 when he wrote in The Promise of American Life, “The democratic principle requires an equal start in the race, while respecting at the same time an unequal finish.”

However, Croly added, “The chance which the individual has to compete with his fellows and take a prize in the race is vitally affected by material conditions over which he has no control.” The problem, added Croly, was that under “a legal system [such as America’s] that holds private property sacred there may be equal rights, but there cannot possibly be any equal opportunities for exercising such rights.”REF

The idea that equality of outcome was a desired result, and that it required state intervention, had divided liberalism in the 19th century. Liberals entered the 19th century believing, with Adam Smith, that the individual should be given wide sway in determining his self-interest and acting accordingly to improve his own material conditions. However, the enormous wealth that such an approach created, especially when combined with the Industrial Revolution, produced inequalities that were no longer relegated to village life, but were concentrated in urban areas where they could be seen by Charles Dickens and Karl Marx. “The trunk of liberalism now separated into two boughs” in the 20th century, James Traub wrote in The Atlantic in 2018.REF One side remained staunchly free market. That side went with Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and others. The other bough went with Isaiah Berlin, Karl Popper, and journalists like Traub, in the belief that the state should intervene by taxing the successful and transferring that wealth to the less so. Both sides called themselves liberal, creating much confusion.

Under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, these wealth transfers grew, as private property lost some of the sacred character that so irritated Croly and his fellow progressives, and as the principle that the government should step in to help the less fortunate gained wider acceptance. FDR’s 1935 National Labor Relations Act includes the first use of the phrase “affirmative action,” and it compelled employers to take measures to compensate workers whom they had harmed through unfair labor practices, which were usually aimed at union members.REF

Starting with Johnson’s Howard speech, however, the President of the United States was now saying that the qualifying criteria for government intervention would include not just the fluctuating needs of a socioeconomic class but also the fixed identities of race and national origin—to which sex would be added years later.

This introduction of race as a qualifying factor was not haphazard. Moynihan sensed that he was doing something new, as he dwelled on the salience of race at length in subsequent writings. “[T]raditionally, the American legal and constitutional system has been based on a deliberate blindness to any social reality other than the reality of individuals,” Moynihan wrote in Commentary two years after the speech. This individualistic approach, which Moynihan rightly observed derived “partly from the metaphysics of classical liberalism,” had been altered to consider class in the New Deal, but race was still a step too far. “The reality of class had to be acknowledged, for example, in order for the labor movement to make the gains it did under the New Deal. But if this understanding of the Negro in group terms has been widespread enough among scholars, it has not been a consideration in the framing of programs.”REF

All of this made a huge difference and tapped a vein of popular opposition to racially based decisions that has never abated. That government would once again make decisions based on a person’s race has never gained a fraction of the acceptance that needs-based wealth transfers or state intervention to protect workers against unfair labor practices obtained, which is why racial preferences in university admissions have kept returning again and again to the Supreme Court, in the same way that Roe v. Wade did after it was decided in 1973, until it was finally struck down in Dobbs v. Jackson in 2022. In Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003 and in the two Fisher v. University of Texas cases (in 2013 and 2016, called Fisher I and Fisher II), Americans kept coming back to the Court essentially to relitigate Bakke and reverse what they sensed was a grave injustice.

This was not only because making race-based decisions so clearly betrayed all the promises made by Kennedy, Johnson, Humphrey, and all the other promoters of the Civil Rights Act, including Martin Luther King, Jr., who in 1963 longed to live in a nation where his four little children would “not be judged by the color of their skin.” Nor was it just that the Constitution, in its Fourteenth Amendment, prohibits any government from denying “to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,”REF or that the Civil Rights Act itself bans discrimination on the basis of race in employment and institutions of public education. Nor was it just that in a system where race is the deciding factor, a rich member of a given race could be given a benefit denied to a poor member of another. All these arguments weigh heavily, but there was something even deeper. Americans have intrinsically understood that treating people differently because of immutable characteristics violates the principle of equal dignity, upon which a democratic and just society is based.

Family Policy. Moynihan intended to use race only to rescue the black family, especially from the scourge of out-of-wedlock births, which were then rising rapidly among black Americans (though the rate was much lower than it is today). “[I]llegitimacy—which [Gunnar] Myrdal judged the best measure of family stability—is a serious problem for Negroes (and increasingly for whites as well),” Moynihan wrote in Commentary. What he wanted was “to urge consideration of a new and different kind of policy, in addition to the more familiar ones—namely, a national family policy.”REF (Emphasis in original.)

But, family policy was completely struck out of the civil rights movement. Once it became official government policy to ignore the leading cause of racial disparities (family breakdown), all the nation was left with was the concept that the gaps were solely, or at least primarily, caused by discrimination, and that only racial preferences could remedy things.

Johnson, in his Howard speech, dwelled on the black family at length, becoming the first President to speak about the problem in public, according to Moynihan. As he detailed the many reasons why black Americans were falling further behind, Johnson said, “Perhaps most important—its influence radiating to every part of life—is the breakdown of the Negro family structure. For this, most of all, white America must accept responsibility. It flows from centuries of oppression and persecution of the Negro man.”REF

Johnson then announced that in the fall there would be a White House conference of scholars, called “To Fulfill These Rights,” to address the problems of the black family. The problem was “not pleasant to look upon,” said Johnson, but,

it must be faced by those whose serious intent is to improve the life of all Americans.

Only a minority—less than half—of all Negro children reach the age of 18 having lived all their lives with both of their parents. At this moment, tonight, little less than two-thirds are at home with both of their parents. Probably a majority of all Negro children receive federally aided public assistance sometime during their childhood.

The family is the cornerstone of our society. More than any other force it shapes the attitude, the hopes, the ambitions, and the values of the child. And when the family collapses it is the children that are usually damaged. When it happens on a massive scale the community itself is crippled.

So, unless we work to strengthen the family, to create conditions under which most parents will stay together—all the rest: schools, and playgrounds, and public assistance, and private concern, will never be enough to cut completely the circle of despair and deprivation.REF

In fact, the plight of the black family, and what to do about it, was intended to be the central aspect of Johnson’s Howard speech, and to his efforts going forward. Moynihan said that a major report that he had authored at the Labor Department earlier that year, on the troubles brewing in the black family, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” had made it to Johnson’s desk a month before the Howard speech. In his 1987 book Family and Nation, Moynihan said that his report was the “thesis” for the speech.REF In an article he wrote for Commentary in 1967, Moynihan called his report “the original precipitant of the Howard Speech.”REF

Moynihan had been incredibly prescient in his report. Indeed, as its title put it, the report was a call for national action. It was replete with statistics showing how Moynihan had perceived, earlier than most, that the breakdown of black family structure, the rise of out-of-wedlock birth rates, was at the heart of the racial disparities. This was stated throughout. In the report’s very first page, Moynihan wrote:

The gap between the Negro and most other groups in American society is widening. The fundamental problem, in which this is most clearly the case, is that of family structure. The evidence—not final, but powerfully persuasive—is that the Negro family in the urban ghettos is crumbling. A middle-class group has managed to save itself, but for vast numbers of the unskilled, poorly educated city working class the fabric of conventional social relationships has all but disintegrated.REF

So, the country had a chance to recognize and potentially deal with the central problem causing the widening racial gaps. To be sure, Johnson’s speech did contain the initial seeds of government intervention on the basis of race, but it also included a call for a conference of scholars and sages that could have dealt with the central problem, a gathering where Moynihan’s presence would have been large. The country might have solved the problem and brought Americans of all colors to the starting gate with more similar starting conditions. But, instead, the country spent the following 60 years trying vainly to rig outcomes by government fiat through picking participants by race, thereby triggering more division and animosity instead of less.

Moynihan lamented in a letter to journalist Philip Gailey in 1992, “We lost a generation because the White House staff under LBJ simply lost its nerve.”REF

Why that happened is instructive. Two months after his Howard speech, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the other landmark act of the civil rights era, and everything seemed to be on track. But the Voting Rights Act marked “the peak of optimism for the civil rights movement,” as the anti-segregationist Yale historian C. Vann Woodward put it.REF Five days later, the Watts section of Los Angeles, a predominantly black neighborhood, exploded in riots, which went unabated for seven days. Woodward, who had marched with King at Selma, called it the worst racial violence in American history. At the end, 34 people were killed (all but three black), 1,000 were injured, and 4,000 were arrested, with 600 buildings damaged, one-third completely burnt. In the end, it took the Army to end the violence.

The riots “created an atmosphere of fear and threat, and counterthreat, in which the era of good feeling could not survive,” wrote Moynihan.REF The Moynihan Report became the quick explanation as to why such violence had erupted at a time when government was finally recognizing the civil rights of black Americans and had signed acts ending legal discrimination, and despite the fact that black Americans were making real economic advances. And, in effect, the breakdown of the family had indeed contributed to the pathologies that led to Watts. “At the heart of the deterioration of the fabric of Negro society is the deterioration of the Negro family,” Moynihan’s report had warned.REF And Moynihan detailed that the dissolution of the black family was a much greater problem in Northern ghettos than in Southern rural areas.

Watts also created a panic among many sectors, not least among white elites in the North, who in the end chose to placate the loudest, and even separatist, voices in the black communities rather than explore the causes of the trouble with a troublemaker from the Labor Department. “The real blow was Watts,” wrote Moynihan. “Watts made the report a public issue, and gave it a name.”

A whispering campaign began against Moynihan and his report within the civil service—already a problem, which Moynihan’s colleague Arthur Schlesinger was the first to see as a “permanent government” trying to thwart the “presidential government”—because the report and the speech had come from political appointees. Others then piled on.

The Nation accused Moynihan of “subtle racism,” and of seducing “the reader into believing that it is not racism and discrimination but the weaknesses and defects of the Negro himself that account for the present status of inequality.”REF Worse was the indictment from black civil rights leader James Farmer, who said that “Moynihan has provided a massive academic copout for the white conscience and clearly implied that Negroes in this nation will never secure a substantial measure of freedom until we stop sleeping with our wife’s sister and buying Cadillacs instead of bread.”REF

And that was the end of any talk of family dissolution, and what might be done about it. When people did meet at the White House for the conference that Johnson had called for, the issue of family was stricken from the proceedings. Moynihan quoted White House official Clifford Alexander as simply stating, “The family is not an action topic for a can-do conference.”

Nurturing Dreams and Nurturing Society. Once the exploration of family breakdown as the main culprit ceased, schools led the way with racial preferences.

Eventually, a California student by the name of Allan Bakke brought the issue of quotas to the Supreme Court. Litigation was inevitable because, as discussed, they so offend the American ideal of equal dignity that was ratified by the Civil Rights Act. That Americans would reject the use of race had been Moynihan’s biggest blind spot—he seems not to have foreseen that a return to race-based policy would be widely rejected. In a four-four-one decision that is explained below, Justice Lewis Powell made a distinction between outright quotas, which he rightly found unconstitutional, and using race as one of many elements in a holistic approach that had to be narrowly tailored and pass strict judicial scrutiny to be constitutional.

But to get there, the white liberal establishment had to go through logical contortions. In a separate opinion that concurred with a part of Powell’s, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote, for example, that “[i]n order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently. We cannot—we dare not—let the Equal Protection Clause perpetuate racial supremacy.”REF

Here, the justice was echoing an Atlantic article about the Bakke case by McGeorge Bundy, who had written, “Precisely because it is not yet ‘racially neutral’ to be black in America, a racially neutral standard will not lead to equal opportunity. To get past racism, we must here take account of race.”REF

As Moynihan bemoaned in the Commentary piece about the abandonment of family policy, “the misery is that it did not have to happen.” But a coalition had joined hands on not exploring causes, least of all family, and utilizing only the corner-cutting strategies of racial preferences to try to manage outcomes. To Moynihan, the opposition emanated from “Negro leaders unable to comprehend their opportunity; from civil-rights militants, Negro and white, caught up in a frenzy of arrogance and nihilism; and from white liberals unwilling to expend a jot of prestige to do a difficult but dangerous job that had to be done, and could have been done. But was not.”REF

Yale historian Woodward concluded that it was the result of a tacit agreement between the black bourgeoisie, which needed jobs in the bourgeoning civil rights bureaucracy, black separatists who wanted revolution, and a suddenly panicked Northeastern white elite. “For some Yankees,” wrote Woodward in his masterful The Strange Career of Jim Crow, “guilt temporarily got the better of prudence, and at times it was a question of whether it was guilt or cowardice that prevailed.”REF

The dearth of any discussion on family has left the country only with racial preferences as a supposed remedy for disparities that are judged to be proof of racism, these days characterized as “systemic.” As Harvard’s Glenn Loury explained as far back as 1985, “The civil rights approach has two essential aspects: first, the cause of a particular socioeconomic disparity is identified as racial discrimination; and second, advocates seek such remedies for the disparity as the courts and administrative agencies provide under the law.”

The problem is that—as Moynihan discovered as far back as the 1960s, Loury explained in the 1980s, and is much more so the case today—disparities by themselves are not evidence of discrimination. This is why, as Loury continued, using these civil rights strategies “to address problems for which they are ill-suited thwarts more direct and effective action. Indeed, the broad application of these strategies to every case of differential achievement between blacks and whites threatens to make it impossible for blacks to achieve full equality in American society.”REF

Black commentator Shelby Steele says that accepting racial preferences as a strategy for starting out with equal opportunities was the “worst mistake” black America ever made, and charges moreover that Johnson only made the proposal so that U.S. institutions could regain the moral authority they had lost when the nation collectively admitted the great sin of segregation.

“It probably worked out very well, as a program that gained moral authority,” he told C-SPAN in an interview in 2006.REF

Blacks, on the other hand, listening to a president saying “we’re now going to make up to you, we’re going to do right by you, we’re going to bring you up to the starting line,” as he talked about in his Howard University speech, and “we’re going to give you what it takes to compete with others, and so forth,” we made at that moment the worst mistake in our entire history, I believe, which is that we put our faith back into the hands of the society that had just oppressed us for four centuries, and we said, all right, you did it to us and you must now be responsible for getting us out of this circumstance, bringing us to full equality in your society.

Whites, adds Steele, then used that responsibility not to truly help blacks, but “to win moral authority.” What black Americans must tell themselves, continued Steele on C-SPAN, is

We’re free. I’m free. You’re free. There may be a small degree of racism left in American life, but the larger truth is that you are free in this society to make whatever kind of life you want to make for yourself. You can nurture any dreams that you want to nurture in this society, and you are going to be free. Not only are you going to be free to pursue them, but in many cases, this society today is behind you. It’s not in front of you keeping you down. It’s behind you supporting you.

Now that the Supreme Court has removed from the life of the nation the Faustian bargain that racial preferences tempted many with, and if what American society truly wants to do is fulfill the rights of all Americans, then it must reinforce to all Americans that there is equality of opportunity available to all which cannot guarantee equal results. Part of being free is exploring what holds people back and attempting to address it. That, of course, means exploring the questions about family breakdown (and many other issues, such as bad schools, crime, social media, omnipresent pornography, and high divorce rates) that a coalition prevented Moynihan from asking, and which do indeed thwart equal starting conditions.

This does not necessarily mean that the government needs to have a “family policy” now, as Moynihan wanted back then, least of all using preferential treatment based on race. But a different approach to family formation now beckons, as Loury says. This will not be easy. As Moynihan wrote, “It is plain enough that anyone seeking to discredit a political initiative based on as sensitive a subject as family structure, particularly that of Negroes, will have no difficulty devising arguments.”REF And yet there is now no other choice but to go unto that breach. After this Supreme Court decision, the nation must pivot and adopt an all-of-society exploration of the causes of family breakdown, and of remedies that will help the country to end it.

The Mismatch Problem

For decades, researchers and civil rights advocates tried to draw attention to the harm caused by racial preferences. Yale Law School professor Clyde Summers discussed the “mismatch” effect of racial preferences in 1969, shortly after racial preferences became a common practice in higher education.REF Summers, who had previously written in opposition to racial discrimination in labor unions, was not making an ideological point but appeared authentically concerned about the negative effects of racial preferences through student mismatch.

The “mismatch” theory has since been proved time and again by researchers using data from different colleges, universities, and law schools. The concept of mismatch is illustrated as follows: If an institution adds points to a student’s academic index because of his or her race, the student’s academic qualifications may not match the school’s requirements and the qualifications of other students. As a result, the student is more likely to struggle with the academic workload, fall behind others, and even fail to complete his or her degree. As explained earlier, some higher education institutions use racial preferences in their admissions processes by adding points to a student’s academic index scores. This index is often composed of a student’s GPA, high school grades, college or graduate school admissions test scores on the SAT, ACT, or Law School Achievement Test (LSAT), and other factors, such as class rank (a student’s academic achievement).

As Sowell explains, using law schools as an example,

Given that law schools, like the rest of the academic world, have a whole hierarchy of work standards, and a corresponding hierarchy of admissions standards, the issue was not whether a minority student was “qualified” to study law and become a lawyer, but whether his particular qualifications were likely to match or mismatch the institutional pace, level, and intensity of study under preferential admissions policies. While this issue was raised as regards law schools, the principle applies to the whole academic world.REF

Schools calculate applicants’ academic indices in different, though similar, ways. In Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It, Richard Sander and his co-author Stuart Taylor, Jr., provide examples of academic indices that start at 0 and go to 1,000 points.REF Students can receive hundreds of points for their SAT score and high school GPA, and graduate school students receive points for their Graduate Record Exam (GRE) score or LSAT score.REF For example, an applicant’s GPA as measured on a four-point scale is multiplied by a figure to make the value worth hundreds of points. Similar calculations are made using ACT college admissions test results (which are measured on a scale from one to 36) and SAT results so that, when combined, the total is summed to represent a figure on a 1,000-point scale.REF

In No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal, Thomas Espenshade (a supporter of racial preferences, according to Sander) and Alexandria Walton Radford show that racial preferences can result in large increases in a student’s academic index, equivalent to 310 points on the SAT or 155 total points on a student’s index—a 15.5 percent boost. Sander, whose 2005 article in the Stanford Law Review on mismatch attracted the attention of many in the academic world, says that racial preferences are not “tie breakers” between black students and their peers, but clear evidence of priority treatment based on race.REF

Sander began documenting the academic and other harms from mismatch in the late 1990s after California voters approved Proposition 209 in 1996, which prohibited public employers, such as the California university system, from using racial preferences in hiring or admissions. Though university regents rescinded this ban on racial preferences in 2001 (with the support of newly elected Governor Gray Davis), the period between 1996 and 2001 provided a natural experiment on the use of preferences.REF

After Prop 209 passed in 1996, the elimination of racial preferences did not dissuade highly qualified minority students from applying, as some critics had predicted. The percentage of the academically strongest black students applying to the most selective school in the university’s system, the University of California at Berkeley, increased from 58 percent in 1997 to 70 percent in 1998.REF Then, the yield rate—the rate at which students who are offered a seat at a college accept their admissions letter—was 52 percent for black students, “the highest in many years and probably an all-time record,” Sander and Taylor wrote.REF But that is not all.

Sander and Taylor explain that after the passage of Prop 209 and the ban on racial preferences, graduation rates for black students “rose rapidly.”REF Four-year graduation rates for black students increased from 22 percent to 38 percent, and six-year graduation rates increased from 63 percent before the proposition to 71 percent after.REF Other research by economists from Duke University on the University of California system before and after Prop 209 also found increases in graduation rates of three to seven percentage points overall for black, Hispanic, and Native American students after racial preferences were abolished.REF

Fears that eliminating racial preferences would result in fewer black students entering or finishing college were not realized. Why? Because the highest-performing minority students were still admitted to the most competitive institutions—and succeeded there. But the next tier of students was not admitted to the more competitive schools where students with academic records such as theirs had struggled before. Rather, they were admitted to schools that better matched their academic preparation, and so the students were more likely to complete their course of study.

New research from Sander on law school student mismatch finds that “mismatch can account for two-thirds to three-quarters of the Black-white gap [in bar passage rates], as well as more than half of the Hispanic-white gap.”REF (Emphasis in original.) Sander explains that “a student’s degree of mismatch in law school is by far the strongest predictor of whether he or she will pass a bar exam on a first attempt.”REF

The failure to succeed in a school where the rigor does not match a student’s academic ability is the most measurable harm from mismatch. Law schools provide a fitting example, but not the only one. In 1996, Rogers Elliott and A. Christopher Strenta led a team that investigated the use of racial preferences at Dartmouth and found that black students with lower scores in high school were more likely to drop out of rigorous science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) programs at the college.REF These findings were supported in 2004 by research using a much larger dataset from the College Board. Here again, researchers found that prior academic performance helped to predict success in postsecondary STEM programs.REF Significant numbers of minority students were dropping out of STEM fields in college, making this research critical to understanding the causes. To date, college officials and policymakers have not used these findings to revise admissions practices.REF

The mismatch caused by racial preferences also negatively affects black students’ grades and class ranking and potential for dropping out of school.REF Yet in the years following Prop 209, the graduation rate of black students from colleges in the University of California system increased substantially. Sander and Taylor write:

For the six classes of black freshmen who entered UC schools in the years before race-neutrality (i.e., the freshman classes of 1992 through 1997), the overall four-year graduation rate was 22 percent. For the six years after Prop 209’s implementation the black four-year graduation rate was 38 percent.

That figure compares to an estimated 57 percent four-year graduation rate among white students.REF Sander and Taylor argue that administrators had been working “to conceal” the use of preferences, which means that the graduation rate for black students could have been even higher absent college officials’ activities.REF Officials at the University of California–Los Angeles, for example, “performed elaborate gymnastics to keep black numbers [for admission] as high as they were [before Prop 209]” by admitting black students with lower SAT scores than those of their white peers.REF

Other university systems and college accreditors have also explicitly pledged to ignore bans on racial preferences. After Michigan voters approved a proposition similar to California’s Prop 209 in 2006, University of Michigan president Mary Sue Coleman said that she would “consider every legal option available” to get around the new ban.REF In her speech following the vote, she said, “I am deeply disappointed that the voters of our state have rejected affirmative action” and “we pledge to remain unified in our fight for diversity,” making no mention of the mismatch research that was the subject of a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR) hearing just five months earlier.REF State and college leaders’ attempts to resist bans on racial preferences have been so significant that we provide a longer discussion of the topic below under “Colleges Will Try to Circumvent the Prohibition of Racial Preferences.”

The last example we provide on the harm from mismatch comes from the testimony of students themselves on the damage to their attitudes and confidence caused by racial preferences. Minority students report lower levels of confidence as they are mismatched to schools that do not align with their abilities and preparations and who therefore struggle after admission. Sander and Taylor write, “We have a terrible confluence of forces putting students in classes for which they aren’t prepared, causing them to lose confidence and underperform even more while at the same time consolidating the stereotype that they are inherently poor students.”REF

Mismatch does not merely create hurt feelings—though it does that. Mismatch demonstrates that academic preparation is essential for success in competitive fields, such as law and science. When students who may have been moderately successful in high school are admitted to more selective colleges, their performance makes them look inadequate by comparison, when the students clearly have abilities to succeed at other colleges. Being relegated to the bottom of the class because of different levels of preparation creates the stereotype that black Americans, as a group, are underperforming, regardless of the level of academic rigor—when, in reality, it reflects the policy of racial preferences matching them with schools that are incompatible with the students’ K–12 preparation.

Summers also observed this problem, years before the mismatch research of the late 1990s and early 2000s by noting an “intense anxiety and threat to the student’s self-esteem” caused by the mismatch.REF “Several studies,” writes Sander, “have found that large racial preferences are directly associated with more negative self-images among the recipients.”REF Again, “self-doubt” is more than merely another example of students taking offense at trivial matters—acting like “snowflakes.” The doubt leads to later academic and professional failures. Student testimonies demonstrate this reality, while also reinforcing the results from mismatch research and the observations of Summers and others. In the USCCR’s report from its 2006 hearing on racial preferences and the American Bar Association, commissioners included an e-mail sent by a student at the University of Colorado School of Law to the school’s dean. The student wastes no time in saying that racial preferences did not help him, but rather hurt his academic career and may have ruined his professional prospects:

I do not believe The University of Colorado School of Law (CU) should have admitted me into this school in the first place. CU has known year after year, decade after decade that underqualified students such as myself consistently fall in the bottom 5 percent of the class and disproportionately fail the Colorado Bar Exam. Nevertheless, CU has done nothing that effectively helps underqualified students receive grades that fall within the “bell curve.”REF

The student then explains that the harm goes well beyond just grades and career opportunities. He writes, “If my brown skin has helped ‘advantaged’ black and brown students feel less isolated (and I really don’t believe they feel isolated) at CU, I am happy for them…. The problem, despite my professed happiness, is that CU has used my skin color against me in order to provide benefits to others.” The student explains that, had he been more properly matched with a school that fit his academic performance, he would be looking forward to graduation, even if he was finishing at a lower-tiered school than the University of Colorado.

Colleges Will Try to Circumvent the Prohibition of Racial Preferences

Although many colleges stand to benefit from the elimination of racial preferences as a result of increased enrollment, some will almost certainly attempt to continue the use of the practice, despite the high court’s decisions. Colleges and universities will continue trying to engineer the racial makeup of their student bodies despite the constitutional prohibition of racial preferences in admissions.The battle for equal treatment will shift to colleges’ new strategies, some of which will be less defensible than others.The battle for equal treatment will shift to colleges’ new strategies, some of which will be less defensible than others.

First, since grit and perseverance are admirable characteristics correlated with an array of positive life outcomes, colleges will continue to seek evidence of hard work and overcoming obstacles that go beyond quantitative grades and test scores. However, this allowance for evidence from personal essays and letters of recommendation is likely to gain heightened prominence in admission decisions, since these documents can often reveal racial identity. Since assessments of virtue tend to be highly subjective, colleges will find ways to hide racial preferences within seemingly race-neutral reviews of personal characteristics. While Harvard University’s data showed abuse of its personality score, a score given to students in the application process based on certain traits, the analysis was complex.REF Colleges will probably try to get away with preferences until they lose in court. Transparency plus severe penalties if caught should help to mitigate such schemes.

Second, pre-admission and post-admission schemes are likely to become more prevalent. Despite the ban on racial preferences in California, the University of California at Berkeley realized that the prohibition only referred to admissions, not recruitment.REF The old form of “affirmative action” that meant, for instance, making sure to advertise in untraditional outlets and recruit from a wide range of high schools in order to find the best candidates wherever they might be, remains legal and desirable. But Berkeley and many other institutions have gone further, running unlawful race-based programs and awarding unlawful race-based scholarships.

Colleges unlawfully discriminate when they offer recruitment or yield programs exclusively or preferentially to non-white students. Such programs must be clearly available to all prospective or admitted students. Likewise, colleges may not have race-based scholarships that give more funding to members of certain identity groups. Moreover, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has long interpreted discrimination by colleges to include advertisements of third-party discriminatory scholarships. Such prohibited advertising would still be unlawful if a registered student organization is enlisted to tell prospective or admitted students about such a scholarship. There is no lawful route for differential treatment of prospective or admitted students by race.There is no lawful route for differential treatment of prospective or admitted students by race.

Instead, any aspect of the admissions process that has a disparate impact by race will be downgraded or removed entirely. This is why, pre-emptively, so many colleges and graduate programs have stopped requiring standardized tests. To the extent that such tests remain reliable indicators of future success at the institution and in one’s profession, removing them is a dire mistake.

For example, colleges may try to make the eligibility provisions for university programs so narrow that the criteria are indistinguishable from policies based on racial preferences. For example, at the University of San Diego, school officials created the Black InGenious Initiative (BiGI) in 2022, which, as the title indicates, was originally created exclusively for black students. The San Diego Foundation’s announcement upon the program’s launch said, “BiGI is designed to uplift Black students in San Diego County.”REF While a private foundation that receives no federal funding can create a program to help individuals based on skin color, a public university cannot enroll students exclusively because of skin color or ethnicity. The OCR opened an investigation into the program, and the university then stated that students from all races were eligible to apply. Yet officials would now select participants based on narrow criteria which make it difficult to distinguish non-black applicants from their black peers.

According to the OCR:

Since opening this complaint for investigation, the University has taken steps to make clear that the BiGI program is open to students regardless of race. Specifically, while designed to uplift “the brilliance of Black students in San Diego County,” the program is open to students from 6th through 12th grade regardless of race.REF

Yet the program’s website stresses that the program is designed to serve black students. In a letter concerning the investigation of the program’s website, OCR officials state that “the focus of the program is on Black student problems and solutions.”REF

For students of other races to be selected, they must demonstrate that they have experienced discrimination similar to the prejudice faced by black Americans. The OCR wrote, “Because of BiGI’s focus on remedying disproportionality, if other non-Black members in the community face similar barriers to academic success, and have documented experiences of significant disproportionality, the BiGI program welcomes their applications too.”REF Thus applicants who are not black must show that their lives and experiences are essentially indistinguishable from black individuals who have faced specifically anti-black discrimination.

Black student applicants, meanwhile, are automatically considered because of their race, regardless of whether they faced discrimination—while applicants of other races have to prove they have experienced discrimination.

The selection criteria are so narrow that they could allow schools to practice racial preferences by automatically making black students eligible but forcing students of other races to demonstrate discrimination similar to that experienced by black individuals of prior generations in order to be competitive in the selection process.

Those monitoring how higher education officials revise school policies in response to the Court’s latest decision must also provide oversight of accreditors. College and graduate program accreditors have pressured colleges and universities into using racial preferences. For example, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights highlighted a brazen policy adopted by the American Bar Association (ABA) in the early 2000s. The ABA, which accredits law schools, adopted an operating policy that stated law schools must show “concrete action” to promote the enrollment of minority law students (called Standard 212). Then, the ABA went further and said that law schools should ignore statutes and even constitutional provisions that prohibit racial preferences. Interpretation 212-1, the first Interpretation of Standard 212, says:

The requirement of a constitutional provision or statute that purports to prohibit consideration of gender, race, ethnicity or national origin in admissions or employment decisions is not a justification for a school’s non-compliance with Standard 212. A law school that is subject to such constitutional or statutory provisions would have to demonstrate the commitment required by Standard 212 by means other than those prohibited by the applicable constitutional or statutory provisions.REF

The ABA even suggested specific ways that schools could take “concrete action,” in addition to racial preferences, such as creating “a more favorable environment for students from underrepresented groups.”REF The USCCR conducted a 2006 hearing that discussed the ABA’s policy because some commissioners believed that the ABA had designed these provisions to go beyond what the ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger allowed. Because the ABA is an accreditor for law schools, giving it significant power to influence school operations in accordance with the accrediting process, some commissioners feared that the ABA’s new policies “would pressure law schools to employ [racial preferences] in admissions.”REF

The ABA showed clear intent to circumvent court rulings that limited the use of racial preferences. In his testimony before the USCCR, George Mason University School of Law (now the Antonin Scalia Law School) professor David Bernstein said, “Ever since the Court decided Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003, ABA accreditation officials have been pressuring law schools to use, or increase the use of, racial preferences, using their accreditation authority to blackmail the schools.”REF The ABA would revise its policies based on modest changes to the interpretations, but its intent was already clear. Accreditation is a powerful cudgel, as it serves as the gatekeeper to federal student loans and grants. Using both overt and covert means, the ABA had told school officials that they should not allow court opinions or laws to prevent them from using racial preferences to manipulate the makeup of their student body.

“Equity” vs. “Equal Opportunity”

Ibram X. Kendi is an influential figure in American politics and culture. He is the founder of the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research and the author of several books, including How to Be an Antiracist. His definitions of “racism,” “antiracism,” “equity,” and “inequity” have been promoted in K–12 education, government, journalism, and corporate America. According to Kendi:

A racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups. An antiracist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial equity between racial groups. By policy, I mean written and unwritten laws, rules, procedures, processes, regulations, and guidelines that govern people. There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.REF

While dictionary definitions of “equity” suggest the “quality of being fair and impartial,” the Kendian version of the term is used most frequently to compare the social outcomes of different ethnic groups. So, in practice, equity must mean that the government or private-sector actor must treat individual Americans differently, and not even according to non-racial criteria, such as need, but based solely on skin color or national origin. This violates American ideals and laws. Kendi, both an author and an activist, and others believe that “Racial inequity is when two or more racial groups are not standing on approximately equal footing.” The justification for racial preferences is largely based on the belief that racist policies, practices, and institutions—both past and present—are the main reason for racial disparities in education outcomes. This is a commonly accepted position among progressives today, but it is important to note that black leaders in previous generations rejected this way of thinking.

Professor S. G. Atkins was founder and president of the Slater Industrial and State Normal School in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the forerunner institution to Winston-Salem State University. Atkins penned a response to the question “Should the Negro Be Given an Education Different from That Given to the Whites?” that appeared in a compilation of essays from African American leaders that were published in 1902:

The great fact is that mind is mind—of like origin and like substance—and that it has been found to yield to like treatment among all nations and in all ages. There is no system of pedagogy that would hold together for a moment if the idea of the unity of the human race and the similarity of mind were invalidated. Philosophy itself would be threatened and all science would be in jeopardy. Investigation and practice never fail to support this theory of the solidarity of the human race. In the schools where it has been tried it has been found not to be a matter of color, nor even of blood—and certainly the differences have not depended on race affiliation. It has been a question of the individual and of local environment.REF

Atkins was born into slavery in 1863, the same year that President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. No one would argue that African Americans are subject to more racism through laws, policies, or social customs today than 160 years ago. Yet despite his social standing, he understood the inherent indignity of creating separate education standards for different groups based on race. Unfortunately, the belief that black students need a different type of education and different standards of evaluation than their white peers is a version of “separate but equal” that is the “progressive” status quo from kindergarten to college.

Conservatives often contrast “equity” with “equality of opportunity.” In the context of K–12 education, “equality of opportunity” is used to describe policies and programs that attempt to get as many students to the “starting line” as possible. This is certainly a more defensible position than changing standards or favoring specific ethnic groups, but it has its own social, economic, and cultural limitations. For instance, no government can guarantee that every child is raised in the same type of family. Some children grow up in homes surrounded by books. Others spend most of their time looking at computer screens and watching television. That said, what government can do is to treat each person equally before the law.

Policy can be designed to address the needs of the disabled. For example, transportation experts use ramps and curb cuts to make sidewalks and buildings accessible to individuals—of every background—who use wheelchairs, walkers, strollers, or have other mobility limitations. No one would suggest that the basis for deploying these measures should be race as opposed to disability.

Equality of opportunity should be characterized by non-discrimination. Its focus in the area of education should allow families and individuals to determine the learning options that will maximize their potential, rather than having the government dictate where they attend school. Equality of opportunity should also acknowledge that even when all these steps have been taken, group outcomes will still differ because American racial categories are composed of different individuals from different regions with different cultures with differences in ability, values, or priorities.

The following hypothetical example demonstrates the difference between “equality” (uniformity of opportunity) and “equity” (uniformity of outcome). A school district’s analysis of SAT results finds significant disparities in scores based on ethnic background and household income. Local stakeholders and media claim that the district is not doing enough to ensure that all children have access to SAT preparation resources. The district responds to these concerns by investing in SAT test prep for low-income students. The classes are free and easy to access, and administrators personally follow up with families about the program. Within three years of implementation, every student in 11th grade and 12th grade has successfully completed at least two SAT preparation classes.