The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) simplified taxpaying for most Americans, cut taxes for individuals and businesses, and updated the tax code so that American businesses and the people they employ are globally competitive. Many of the TCJA’s reforms, however, are temporary and require additional congressional attention. Congress should enhance the TCJA’s success by creating Universal Savings Accounts and reducing subsidy spending in the tax code.

The tax cuts put more money in the pockets of taxpayers, are supporting a healthy economy, and are lifting the wages of working Americans.1 The vast majority of households in every congressional district saw a tax cut in 2018. Average Americans got a $1,400 tax cut, and families of four saved $2,900, primarily through lower employer tax withholdings, which increased after-tax income for workers throughout the year.2

Many Americans are benefiting twice from the tax cuts: first by paying less in taxes and then from the higher wages generated by a faster-growing economy. At the end of 2018, workers received some of the largest wage gains in over 10 years, and unemployment rates were historically low.3 Over the next 10 years, the typical American will benefit from over $26,000 more in take-home pay, or $44,697 for a family of four, because of the larger economy generated by the tax cuts.4

Permanence Is Key

The TCJA reduced federal income tax rates, increased the standard deduction, doubled the child tax credit, repealed the personal and dependent exemptions, and capped the deduction for state and local taxes. Congress made the majority of the TCJA’s provisions temporary, both to comply with procedural rules in the Senate and because of an unwillingness to constrain spending.

Most of the law’s individual tax provisions expire in 2025, and Americans’ taxes are scheduled to increase in 2026. Any budget proposal that does not make the already agreed-upon tax cuts permanent must assume tax increases of over $1,000 for middle-class families.5

Lower tax rates for individuals and businesses have received the most attention from the media, but the TCJA’s adjustments to investment rules bring equally important benefits for American workers through higher wages and more jobs. The U.S. tax code generally imposes years of delay between when businesses pay for an investment and when they can deduct the full cost of that investment on their taxes. This raises the cost of the investment, which slows gains to future worker productivity and thus shrinks incomes.

The TCJA fixed this problem temporarily for some short-lived investments through “expensing,” allowing businesses to write off some new investments immediately. Buildings, such as new manufacturing floor space and storefronts, still have to use the costly and complicated pre-TCJA system, characterized by arbitrary depreciation schedules concocted by federal bureaucrats who often have little to no business experience. The budgetary cost of expanding expensing to all investments is high in the first few years of the reform because of transition costs, but the economic benefits of the new system are well worth the short-term budget impact.

In addition to protecting Americans’ paychecks from higher taxes, a permanent version of the TCJA could increase the size of the economy and further boost Americans’ paychecks. Permanent tax cuts could boost the size of the economy by 2.8 percent over the pre-TCJA baseline, according to an estimate made when the law was passed.6 That is a full percentage point more—or thousands of dollars of additional income per American household—than the expected result of the temporary provisions under current law.

The fiscal year (FY) 2020 Blueprint for Balance recommends that Congress extend the major provisions of the TCJA permanently, reducing revenues by $299 billion in 2029 and $849 billion over 10 years below the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) current-law baseline. Congress should also consider expanding the TCJA expensing provisions, which could temporarily reduce revenues further in the short term.

Universal Savings Accounts and Other Important Reforms

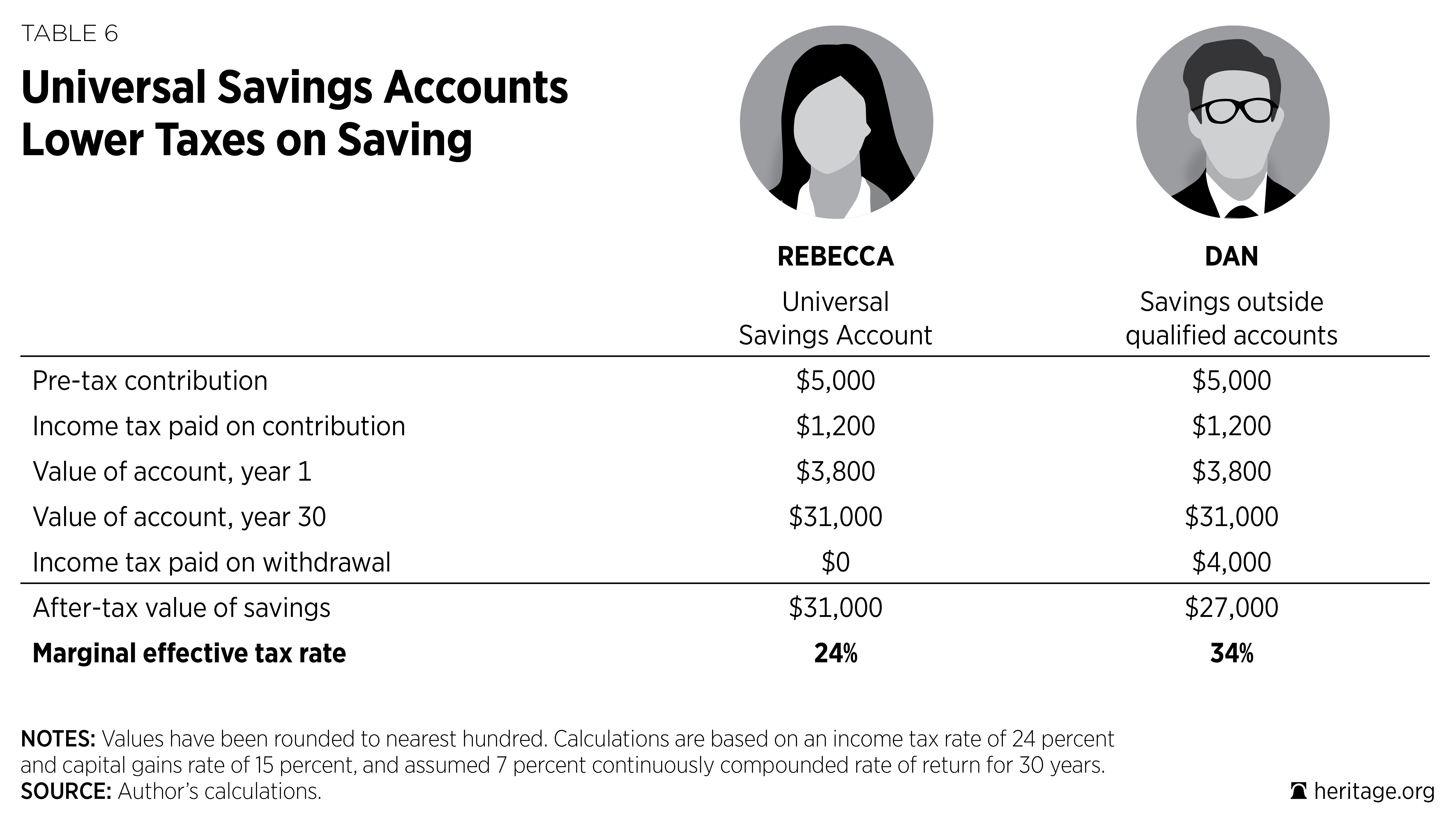

Universal Savings Accounts (USAs) reduce taxes on savings for typical Americans and help families build their own financial security through a single, simple, and flexible account. Unlike holders of existing retirement savings accounts, USA holders would not be bound by limits on when savings can be withdrawn or the purposes for which the funds must be used. Individuals would contribute post-tax earnings, all withdrawals from a USA would be excluded from taxable income, and any gains accrued would thus be tax-free. (See Table 6.) USAs allow Americans at all income levels to save more of their earnings with fewer restrictions on where and when they can spend their own money.7 The limited $2,500-a-year USA included in the Family Savings Act of 2018 would lower federal revenue by $8.6 billion over 10 years.8

USAs should also be paired with important reforms in existing retirement savings accounts. Most Americans are familiar with personal retirement savings accounts, such as 401(k)s and IRAs, but few take full advantage of their benefits. The main impediment to more widespread use of the accounts is their complexity, the cost of compliance, and the regulatory risk for smaller employers.9 The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) lists more than 16 different private retirement accounts, each with its own eligibility rules, income and contribution thresholds, early withdrawal penalties, and employer requirements.10

Depending on employment status, American savers have access to dramatically different levels of retirement saving ability. The patchwork of rules discourages uptake and subdivides individuals’ savings into multiple accounts, often marooned with past employers. Reform should eliminate the multiple sets of rules that govern similar retirement accounts in favor of a more streamlined system that is not necessarily tied to individual employers.

Retirement and general saving reforms are only two of the many important priorities for Congress to consider in the next pro-growth tax package. The estate tax, alternative minimum tax (AMT), and state and local tax deduction (SALT) all should be completely repealed.11 If Congress can control spending—both traditional outlays and spending in the tax code—taxes should be cut further on personal income, capital gains, and business income. These pro-growth reforms would generate higher wages and greater economic opportunity for American workers.

Reducing Spending In the Tax Code

Each year, the tax code is used to hand out Billions of dollars in subsidies to politically connected interests, picking winners and losers and distorting market outcomes. This spending persists without systematic review or annual appropriation. These programs operate like mandatory spending: outlays for which Congress has passed laws making permanent appropriations that it rarely reviews.

Most tax credits—the most popular way to spend through the tax code—are economically indistinguishable from direct spending. A lawmaker may want to subsidize electric vehicles because a new factory is opening in his district. Congress could propose a new program to send $7,500 checks to qualifying purchasers of new electric cars. To meet the same goal, the same lawmaker could instead propose to cut taxes for those who purchase a new qualifying electric car by creating a $7,500 tax credit.

In both cases, the lawmaker dedicates funding to the subsidy program in the federal budget. In the first case, the appropriations are regularly reviewed as part of the annual appropriations cycle, each cycle presenting an opportunity for a proper analysis of trade-offs between this subsidy and other federal spending priorities. Under a system of tax credits, the same outlay is considered off-budget and therefore not subject to any regular review. By changing how it labels the spending, Congress can relable direct government spending as a tax cut.

Tax Expenditures: Not All Created Equal. The concept of spending through the tax code walks a fine line that must distinguish a taxpayer’s retention of his or her own money with an actual government expenditure of someone else’s money. All analysis of tax expenditures, taken to its extreme, wrongly assumes that the government is entitled to spend the entirety of some arbitrarily defined tax base. However, narrowly tailored tax expenditures, which bestow concentrated benefits on select recipients, should be avoided in favor of better-designed tax policy with well-defined rules broadly applied.

Further complicating the analysis of spending through the tax code, the current baseline for measuring tax expenditures as defined by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) rests on an inconsistent definition of income, rendering tax expenditure analysis entirely subjective and unreliable. The government’s calculation of tax expenditures is misleading because it attempts to describe two separate phenomena. Many tax expenditures work to decrease harmful economic distortions by limiting some forms of double taxation that are built into the income tax system. True spending in the tax code (a subset of tax expenditures) comprises special-interest carve-outs, granting privileges to some at the expense of others.12 Lawmakers should not confuse the two.

To distinguish more precisely between types of tax expenditures, Congress should amend the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 197413 to use a consistent consumption tax base rather than the current hybrid income base used for calculation of tax expenditures. The President’s FY 2020 budget includes a second list of tax expenditures using a consumption baseline, revisiting a similar analysis completed in 2006. The JCT should report a similar list. The 1974 act does not preclude producing an additional, parallel accounting of expenditures.14

Tax Credits. A majority of tax subsidies are designed as tax credits, allowing a taxpayer to reduce his or her final tax bill by a set amount, dollar for dollar. The most numerous of these incentives are intended to encourage energy production and energy conservation.

As a policy tool, tax credits are poorly designed incentives; they introduce unnecessary complexity and ambiguity to the tax code and often poorly target the desired activity. Policymakers do no service to various technologies, workers, or companies by subsidizing them. Tax credits for a specific resource, technology, or narrowly described activity manipulate private-sector investment based on political agendas rather than market realities and create competition for subsidies rather than competitive companies.

Lost economic activity is greatest when the tax code, instead of being applied evenly, is applied through a corrupt political process. The government’s use of the tax code to pick winners and losers has harmful economic effects on American families and businesses by limiting their access to diverse products and fostering a less dynamic economy.

Tax credits also obscure overall levels of true spending and revenue collection. The accumulation of special tax provisions increases the complexity of government activity, thereby increasing information asymmetries between government officials and citizens and allowing government budgets to expand beyond their normal democratic constraints. Tax credits contribute to a “fiscal illusion” whereby taxpayers are under the illusion that taxes are cut and government intervention is shrinking. In reality, deficits increase, new market distortions are introduced, and the subsidy escapes regular congressional scrutiny by being exempt from the annual appropriations process. This results in an accumulation of market distortions that slow growth.

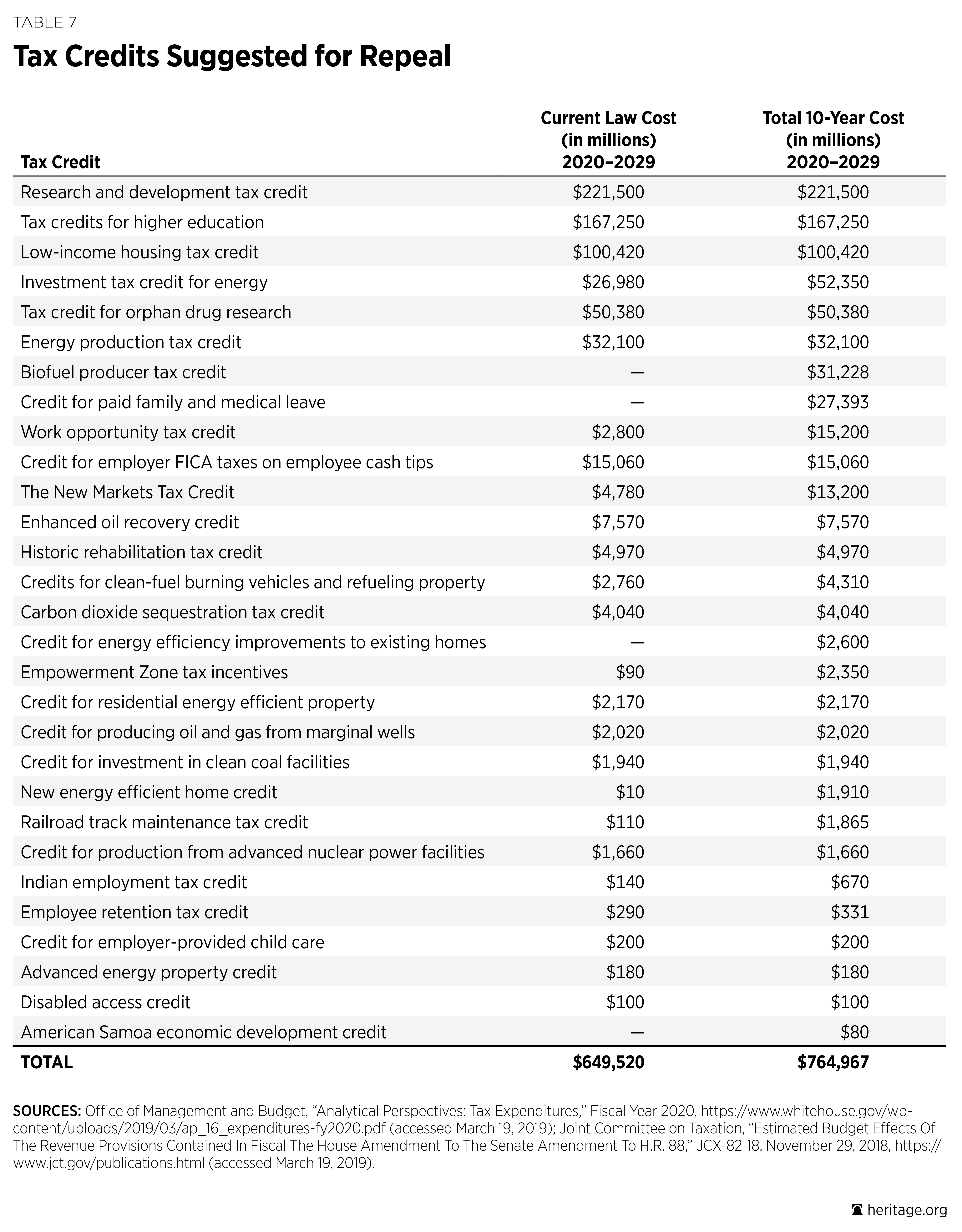

Tax Credits to Repeal. The vast majority of tax credits are narrowly targeted subsidies and should be repealed.15 The Blueprint for Balance recommends repealing the full list of credits in Table 7, the cost of which totals $650 billion over 10 years.16 Many tax credits are authorized only temporarily, but Congress extends them on a recurring basis. The true 10-year cost of these credits, if extended permanently, is $765 billion. Each credit is subject to a variety of specific policy critiques and the more broadly applicable critique that the tax code is not the appropriate tool for distributing subsidies even if they have political or economic benefits. The appendix to this chapter includes details for the individual credits recommended for repeal and their estimated costs.17

Tax Reform Lives and Dies with Spending Reform

Systemic deficits and growing debt will constrain future tax reform efforts and unnecessarily turn any conversation on tax reform into a debate about how to raise additional revenue, imperiling the successes of the TCJA tax cuts. Part of the solution is reducing spending in the tax code, but traditional outlays must also be scaled back. The remainder of this Blueprint offers a wide variety of suggestions for such spending cuts.

The 2017 tax cuts are projected to reduce federal revenues only temporarily. Because many parts of the TCJA were pro-growth (expanding the size of the economy), the tax cuts will raise more yearly revenue by 2024 than was projected before the reform.18 The problems of deficits and debt are driven by too much spending, not too little tax collection.

Chart 5 (see page 15) shows historical and projected spending and revenues under the CBO baseline. Revenues continue to increase as a percent of the economy, but projected spending grows even faster. Without spending-based reforms, it will become increasingly difficult to make the TCJA tax cuts permanent, and as deficits continue to grow, still higher taxes will be required in the future.

Pro-Growth Tax Reform Appendix

Tax Credits Recommended for Repeal and Their Estimated Costs

Tax Credits for Higher Education ($167 Billion).19 The American opportunity tax credit (AOTC) and lifetime learning credit (LLC) are subsidies for higher education tuition and other qualifying expenses. Federal policy should not subsidize any one post-secondary education or training option.

The AOTC is a $2,500 credit, available for the first four years of higher education. If one has a zero tax liability, up to $1,000 of the credit is “refundable,” meaning that it becomes a direct transfer payment. The LLC is a nonrefundable $2,000 credit. Taxpayers cannot claim both credits in the same year, and each has income thresholds at which the benefits phase out.

Much like other federal subsidies for higher education spending, such as federally subsidized loan programs, the AOTC and LLC have contributed to the precipitous rise in the cost of college degrees. The myriad sources of federal funds for higher education have removed any incentive for colleges and universities to keep tuition costs low. The significant increase in college tuition rates only increases student reliance on loans and tax incentives to finance higher education.

Eliminating the AOTC and LLC will help to put pressure on colleges and universities to manage tuition costs and will streamline the tax code by eliminating a source of unnecessary complexity.

Additional Reading

- Mary Clare Reim, “Private Lending: The Way to Reduce Students’ College Costs and Protect America’s Taxpayers,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3203, April 27, 2017.

- Mark J. Warshawsky and Ross Marchand, “Dysfunctions in the Federal Financing of Higher Education,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Mercatus Research, January 2017.

Research and Development Tax Credit ($222 Billion). Capital investments, including research and innovation, are important for a flourishing economy, and tax policy should establish a framework in which such investment is not discouraged. However, tax expenditures should aim to promote neutrality rather than to give some firms or sectors an advantage over others.

The research credit permits a tax credit of up to 20 percent of qualified research expenditures in excess of a base amount and has been shown to have a small and uncertain ability to increase private research spending, amounting to at most a dollar-for-dollar increase in private R&D for each dollar of tax subsidy. Government-incentivized research does not significantly increase measures of innovation and may even reduce the quality of research.20 Low-quality research stems from imprecise definitions of qualified research set by bureaucrats in Washington. It is nearly impossible for governments to target socially beneficial R&D successfully: The best mechanism for development of cutting-edge technologies is the free market, not government bureaucrats.

Because the credit cannot be precisely defined, businesses are incentivized to spend large amounts of time and money lobbying Congress and tax regulators to ensure that the credit is tailored to suit their specific interests. Taxpayers claiming the credit and administrators enforcing it spend large amounts of time and money trying to interpret, litigate, and follow the law. This wastes economic resources that could have gone toward productivity-enhancing investments instead of being expended for rent-seeking.

The complex rules and formulas that govern the R&D tax credit are used chiefly by the largest corporations, leaving smaller competitors at a disadvantage.21 A better and politically neutral way to encourage innovative business investment is to allow all businesses to expense all of their expenditures.

Additional Reading

- Jason J. Fichtner and Adam N. Michel, “Can a Research and Development Tax Credit Be Properly Designed for Economic Efficiency?” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Mercatus Research, July 2015.

Tax Credits for Energy and Environment ($144 Billion). Handouts to the energy industry carry a significant hidden cost to American taxpayers beyond lost revenue. Currently, 13 distinct tax credits for specific energy resources and technologies manipulate private-sector investment based on political agendas rather than market realities.

Private capital is limited. Technologies that do not receive subsidies appear to be more expensive, risky, or unpromising. By shifting the financial risk of energy projects indirectly to the taxpayer through the tax code, the government discourages private investments in projects that lack the government’s blessing but may be more commercially promising. A dollar invested in a company benefiting from a tax credit cannot be invested simultaneously in another company, creating opportunity costs where potentially promising but unsubsidized technologies may not receive investment.

Business models built around taxpayer-funded subsidies also distort the incentive that drives innovation. Preferential tax treatment reduces the necessity for an industry to make its technology cost-competitive, because the tax credit shields a company from recognizing the actual price at which its technology is economically viable. Moreover, targeted tax credits give one technology a government-created price advantage over an unsubsidized competing technology. Companies that do not receive any preferential treatment consequently will lobby for it, demanding a level playing field. The result is a hodgepodge of tax credits that benefit select technologies that Members of Congress support because supporting them benefits their districts or states but harms the country as a whole.

The only way to achieve a truly level playing field is by eliminating all sources of subsidies for all forms of energy. Repealing the following 13 tax credits would be a good first step.

- Investment Tax Credit for Energy ($52 Billion). Tax credits of up to 30 percent of investments in solar and geothermal energy property, qualified fuel cell power plants, stationary microturbine power plants, geothermal heat pumps, small wind property, and combined heat and power property. Phased out by January 1, 2024.

- Energy Production Tax Credit ($32 Billion). Tax credits for certain electricity produced from wind, biomass, geothermal, solar, small irrigation power, municipal solid waste, and hydro. Most expired in 2017 or 2018.

- Biofuel Producer Tax Credit ($31 Billion). Provides a tax credit of up to $1.01 per gallon for qualifying second-generation biofuel.22 Expired on January 1, 2018.

- Enhanced Oil Recovery Credit ($8 Billion). Provides a 15 percent credit for qualified costs, reduced by adjusted value of oil.

- Credits for Clean Fuel–Burning Vehicles and Refueling Property ($4.3 Billion). Tax credit of up to $7,500 for qualifying plug-in electric vehicles. Credit phases out for manufacturers who have sold more the 200,000 vehicles. Credits for two-wheeled vehicles, alternative fuel vehicle refueling property, and fuel cell motor vehicles expired on January 1, 2018.23

- Carbon Dioxide Sequestration Tax Credit ($4 Billion). Tax credit for carbon dioxide captured and disposed of or used as injectant in oil or natural gas recovery.

- Credit for Energy Efficiency Improvements to Existing Homes ($2.6 Billion). Expired on December 31, 2017.

- Credit for Residential Energy-Efficient Property ($2.2 billion). Tax credit for residential purchases of solar panels, geothermal heat pumps, and small wind generators. Expired on December 31, 2017.

- Credit for Producing Oil and Gas from Marginal Wells ($2 Billion). Provides a tax credit for wells that produce less than 1,095 barrel-of-oil equivalents per year.

- New Energy-Efficient Home Credit ($1.9 Billion). Provides contractors a $2,000 tax credit for construction of new energy-efficient homes. Expired on December 31, 2017.

- Credit for Investment in Clean Coal Facilities ($1.9 Billion).

- Credit for Production from Advanced Nuclear Power Facilities ($1.7 Billion). Provides a tax credit of 1.8 cents per kilowatt hour of electricity from an advanced nuclear power facility.

- Advanced Energy Property Credit ($180 Million). Provides a 30 percent investment credit for advanced energy manufacturing projects, up to $2.3 billion in total allocable tax credits.

Additional Reading

- Katie Tubb and Nicolas D. Loris, “Tax Extenders Would Make Energy Companies Dependent, Not Dominant,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3279, January 22, 2018.

Low-Income Housing Tax Credit ($100 Billion). The Low-Income Housing Credit Program (LIHCP) is intended to encourage the provision of low-income rental housing. It achieves its goal poorly and primarily benefits special-interest groups and investors.24

Taxpayers making equity investments in eligible housing projects that offer low-income housing can access a tax credit for a 10-year period. The annual credit is 4 percent of the project cost (a 30 percent subsidy) for projects using tax-exempt bonds and 9 percent for other projects (a 70 percent subsidy). More than two-thirds of the subsidy is captured by investors and parties other than low-income tenants.25

The LIHCP is a complex system that requires developers to expend a considerable amount of energy and money in order to adhere to all of its construction, occupancy, and administrative rules and regulations. LIHCP projects cost 20 percent more per square foot than medium-quality market housing projects and are less cost-effective than other direct subsidy programs.26 The program is widely abused by tenants occupying housing for which they are not eligible, by developers who inflate their costs to receive excess tax credits, and by government officials using their discretionary powers to award credits for personal gain.

The LIHCP should be eliminated, and efforts should be made to increase the supply of affordable housing by reducing the considerable government-imposed barriers to construction.

Additional Reading

- Adam N. Michel, Norbert Michel, and John Ligon, “To Reduce Corporate Welfare, Kill the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4832, March 28, 2018.

Place-Based Tax Incentives ($16.4 Billion). Location-based subsidies have a long history of failing the communities they are designed to help. Government officials, whether in Washington or in state capitals, lack the right knowledge and incentives to centrally plan private investment decisions. The economic literature finds that targeted and place-based economic development incentives are ineffective at meeting their goals and in some cases leave communities worse off than they would have been otherwise.27 Government planning through subsidies breeds local corruption and further reliance on the government. These wasteful programs tend to benefit the well-connected while perpetuating many of the institutional problems that are the cause of economic decline.

Government policy should not pick winners and losers; it should strive to treat everyone equally. The following four economic development tax programs should be repealed.

- New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) ($13.2 Billion). Tax credit worth 39 percent of the cost of qualifying investments in designated Community Development Entities that then invest in low-income census tracts, claimed over seven years.28 The Community Development Financial Institutions Fund (CDFI) within the U.S. Department of the Treasury allocates the $3.5 billion of annual NMTCs through a political application process. The credit expires at the end of 2019.29

- Empowerment Zone Tax Incentives ($2.4 Billion). Employer tax credit worth 20 percent of the first $15,000 in wages of empowerment zone resident workers. Other incentives include tax-exempt bond financing, accelerated depreciation, and capital gains deferral. All incentives expired on December 31, 2017.30

- Indian Employment Tax Credit ($670 Million). Employer tax credit worth 20 percent of the first $20,000 of qualified wages and health insurance costs for Indian tribal members employed on an Indian reservation. Credit expired on December 31, 2017.31

- American Samoa Economic Development Credit ($80 Million). Corporate income tax credit based on business activity in American Samoa.32 Credit expired on December 31, 2017.

Additional Reading

- “Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Communities, and Renewal Communities: Comparative Overview and Analysis,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, February 14, 2011

Tax Credit for Orphan Drug Research ($50.4 Billion). Investments in drugs to diagnose, treat, or prevent qualified rare diseases and conditions are able to claim a tax credit worth 50 percent of qualified clinical testing expenses from the development of what are commonly known as “orphan drugs.” Generally, an orphan drug is designated as such by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Orphan Products Development if it is used for a rare disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people or if there is a reasonable expectation of not recovering the costs of development.

The tax code is not able to provide targeted subsidies to unprofitable products in an appropriate manner. Tax credits are notorious for incentivizing firms to relabel expenditures artificially into the favored class, thereby artificially increasing private tax benefits.33 For example, among a sample of all U.S. pharmaceuticals, 25 percent had one or more orphan drug designations that reached the “blockbuster status” of earning more than $1 billion in profits. Combined, these orphan drugs totaled $58.7 billion in global sales in just one year.34

Additionally, it may not be desirable to increase private expenditures on drugs for a limited number of people. Two scholars writing in the journal Health Policy found that the orphan drug policy has “led to commercial and ethical abuses” by shifting limited resources away from development of drugs that could benefit a broader range of people.35 Redirecting resources away from commercially viable drugs ultimately has unknowable but consequential welfare implications.

Tax Credit for Paid Family and Medical Leave ($27.4 Billion). The TCJA created a new tax credit program for paid family and medical leave. It should be allowed to expire, as it does in current law, in 2020. The employer credit for paid family and medical leave allows a tax credit of up to 25 percent of wages paid to employees on qualifying leave making under $72,000 a year.

The temporary credit is not likely to induce new employers to offer qualifying paid-leave programs. Instead, the benefit will accrue to business owners who already offer such programs as a federally subsidized windfall profit. The narrowly tailored credit rules are likely to derail the impressive expansions of privately provided leave programs that have emerged as a margin of competition for employers to attract talent.

Following in the footsteps of other new federal entitlements, the limited credit is likely to grow over time. In contrast to the seemingly small $2 billion a year cost of the current credit, a credit to fully subsidize 16 weeks of paid leave (the goal of many advocates) would cost well upwards of $300 billion per year or $3 trillion over 10 years.36

Tax Credit for Employer-Provided Child Care ($200 Million). The tax credit for employer-provided child care facilities and services allows employers to claim a tax credit for up to 25 percent of their qualifying child care expenditures, for a credit of up to a $150,000 per year.

The employer-provided child care credit unnecessarily creates an incentive for businesses to compensate their employees with child care services rather than cash wages. All employees, including parents, would be better off if they were allowed to negotiate their compensation mix without mandates and other distortions introduced by government policy. Tying employment to any unrelated service also creates job lock—similar to tying health insurance to employment—whereby employees are less likely to move jobs for fear of losing a particular government-incentivized benefits package.37

Private companies with employees who value the service of onsite child care will still have a private market incentive to provide the benefit absent the federal subsidy.

Tax Credit for Employer FICA Taxes on Employee Tips ($15 Billion). In 1993, Congress created a corporate income tax credit equal to the employer portion of Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) payroll taxes on restaurant employee cash tips over the federal minimum wage.38 This credit effectively allows employers of tipped restaurant employees not to pay their 7.65 percent payroll tax contribution on tip income.

In theory, the credit aligns the IRS and certain employers’ reporting incentives so that the employers have fewer incentives to underreport tip income. In reality, the credit creates yet another administrative hurdle to make paying and collecting business taxes more complicated while subsidizing compensation through tips over traditional wages. Moreover, the credit applies only to the restaurant industry; no other tipped industry receives the subsidy.

The Obama Administration’s FY 2016 Revenue Proposal recommended repealing the credit, explaining that it “costs far more than any positive effect on tax compliance.”39

Railroad Track Maintenance Tax Credit ($1.9 Billion). The tax credit for certain railroad track maintenance (known as the 45G Tax Credit) is equal to 50 percent of qualified railroad track maintenance expenditures and capped at $3,500 per mile of track for class II or class III railroads (regional and short line railroads).40 The credit expired on January 1, 2018. A permanent extension and modification of the credit was included in the first version of the Retirement, Savings, and Other Tax Relief Act of 2018.41

The government should not be in the business of providing subsidies to any private industry, including railroads. Narrowly tailored subsidies to specific industries distort investments by incentivizing companies to invest in otherwise unprofitable businesses. Business should earn enough to cover the maintenance costs of its capital.

Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit ($5 Billion). The federal Historic Tax Credit (HTC) is designed to subsidize the rehabilitation and preservation of historic buildings as certified by the National Parks Service. Following changes in the TCJA, the income tax credit is worth 20 percent of qualifying rehabilitation costs and must be claimed over five years.42

Despite the nostalgic allure of historic preservation, the federal tax credit incentivizes inefficient use of valuable real estate and exacerbates housing supply constraints, raising rental costs. The rehabilitation tax credit subsidizes the preservation of old buildings over new construction. New construction often expands occupancy, increasing supply and lowering prices. The main impediments to new construction are local-level preservation and zoning rules that create historic designations. Without new construction, rental costs rise, and people are quickly priced out of the market, creating large reductions in economic welfare.

The HTC makes existing housing supply problems worse and further entrenches other regulatory impediments to new construction.43 Repealing the credit is a good first step toward making housing more affordable by expanding the housing supply, which will lower rents.

Work Opportunity and Employee Retention Tax Credits ($15.5 Billion). The Work Opportunity Tax Credit, first included in the Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996, is a temporary part of the tax code that has been extended and modified 10 times.44 The credit currently expires on December 31, 2019.

The credit is based on a percentage of the employee’s first-year wages, depending on hours worked and group status. It is generally worth between $1,200 and $24,000 annually depending on the eligible targeted populations, which include Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) recipients, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients, certain veterans, ex-felons, residents of special economic zones, youth summer employees, and the long-term unemployed, among others. The employee retention credit is a 40 percent credit for up to $6,000 in wages paid to an employee of a business in a presidentially declared disaster area.45

Historically low employment among each of the targeted populations is a symptom of institutional problems in other policy areas. Regulatory impediments to opportunity should be removed, not papered over with an inefficient and complex tax credit. For example, minimum wages have the largest disemployment effects among young, low-skilled, and disabled job seekers. Most of these populations are also eligible for many other government assistance programs, including other wage subsidy programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

The work opportunity and employee retention tax credits are an unnecessary and highly complex scheme that should be allowed to expire and not renewed again as originally intended.

Disabled Access Tax Credit ($100 Million). The tax credit for expenditures to provide access to disabled individuals was included in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 199046 to help offset employer costs of complying with the new law, which outlaws discrimination in employment and pay for the disabled. Eligible small businesses are able to claim a credit of up to $10,500 for 50 percent of disabled access expenditures.

Following the ADA’s implementation, disabled employment decreased, indicating that the law unintentionally increased the cost of hiring disabled workers. By one estimate, the ADA increased hiring costs by 6 percent–10 percent, largely because of the increased risk of litigation.47 The disabled access tax credit does not address the fundamental problems characteristic of poorly designed federal employment laws, and using the tax code does not alleviate such regulatory burdens effectively.

Endnotes

- Economic Report of the President, Together with the Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisers, The White House, March 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ERP-2019.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Kevin Dayaratna, Parker Sheppard, and Adam N. Michel, “Tax Cuts in Every Congressional District in Every State,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3333, July 23, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/tax-cuts-every-congressional-district-every-state.

- News release, “Employment Cost Index—December 2018,” U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 31, 2019, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/eci.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Dayaratna, Sheppard, and Michel, “Tax Cuts in Every Congressional District in Every State.”

- Adam N. Michel, Kevin Dayaratna, and Parker Sheppard, “Taxes Will Go Up in Every Congressional District If the TCJA Is Repealed,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4908, October 17, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/taxes-will-go-every-congressional-district-if-the-tcja-repealed.

- Adam N. Michel and Parker Sheppard, “Simple Changes Could Double the Increase in GDP from Tax Reform,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4852, May 14, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/simple-changes-could-double-the-increase-gdp-tax-reform.

- Adam N. Michel, “Universal Savings Accounts Can Help All Americans Build Savings,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3370, December 4, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/universal-savings-accounts-can-help-all-americans-build-savings.

- Joint Committee on Taxation, U.S. Congress, “Estimated Revenue Effects of H.R. 6757, The ‘Family Savings Act Of 2018,’ as Amended, Scheduled for Consideration by the House Of Representatives on September 27, 2018: Fiscal Years 2019–2018,” JCX-80-18, September 27, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5147 (accessed March 22, 2019). Revenue for USAs is not included in the 2020 Blueprint baseline.

- David Burton, “The Tax Code as a Barrier to Entrepreneurship,” testimony before the Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, February 15, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/testimony/the-tax-code-barrier-entrepreneurship.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, “Types of Retirement Plans,” last reviewed or updated July 10, 2018, https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-sponsor/types-of-retirement-plans (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Adam N. Michel, “Four Priorities for Tax Reform 2.0—and Seven Supporting Reforms,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4888, July 16, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/four-priorities-tax-reform-20-and-seven-supporting-reforms.

- Veronique de Rugy and Adam N. Michel, “A Review of Selected Corporate Tax Privileges,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Mercatus Research, October 2016, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/mercatus-de-rugy-corporate-tax-privileges-v1.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- H.R. 7130, Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, Public Law 93-344, 93rd Cong., July 12, 1974, https://www.congress.gov/bill/93rd-congress/house-bill/7130 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Adam Michel, “New Measure of Tax Expenditures to Support Pro-Growth Tax Policy,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4951, April 9, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/budget-and-spending/report/new-measure-tax-expenditures-support-pro-growth-tax-policy.

- Not all tax credits should be eliminated. For example, the credit for taxes paid to foreign governments on personal income earned overseas should be retained; it protects U.S. citizens from double taxation under our worldwide tax system and is a desirable feature of the tax code. Alternatively, Congress should eliminate the taxation of American citizens’ worldwide income and tax only income that is earned in the United States. Kurt Couchman, “It’s Time to Free American Expats from Our Ludicrous Extraterritorial Tax System,” National Review, August 15, 2018, https://www.nationalreview.com/2018/08/american-expatriates-deserve-territorial-income-tax-system/ (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Author’s calculations based on expenditure reports from the President’s budget, various JCT reports, and CBO alternative fiscal scenario revenue projections. Individual credit values are summed; however, the economics of each individual credit and how they interact with one another will vary significantly. Chapter 16, “Tax Expenditures,” in Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2020 Budget of the U.S. Government: Analytical Perspectives, pp. 171–228, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/analytical-perspectives/ (accessed March 22, 2019); Joint Committee on Taxation, U.S. Congress, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the House Amendment to the Senate Amendment to H.R. 88 Scheduled for Consideration by the House of Representatives: Fiscal Years 2019–2018,” JCX-82-18, November 29, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5150 (accessed March 19, 2019); Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2019 to 2029: Budget and Economic Data: Revenue Projections, by Category,” January 2019, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#7 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- See Appendix, “Tax Credits Recommended for Repeal and Their Estimated Costs,” infra.

- Tax Foundation, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Special Report No. 241, December 2017, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20171220113959/TaxFoundation-SR241-TCJA-3.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- All costs listed in this appendix represent the total 10-year current policy costs if the provisions were made permanent.

- Christof Ernst, Katharina Richter, and Nadine Riedel, “Corporate Taxation and the Quality of Research and Development,” FZID Discussion Paper No. 66-2013, University of Hohenheim, Center for Research on Innovation and Services (FZID), 2013, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/69739/1/736810501.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Jason J. Fichtner and Adam N. Michel, “Can a Research and Development Tax Credit Be Properly Designed for Economic Efficiency?” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Mercatus Research, July 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Fichtner-R-D-Tax-Credit.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 26 U.S.C. § 40(b)(6)(B), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/40 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 26 U.S. Code § 30D—New Qualified Plug-in Electric Drive Motor Vehicles, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/30D (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Chris Edwards and Vanessa Brown Calder, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Costly, Complex, and Corruption-Prone,” Cato Institute Tax and Budget Bulletin No. 79, November 13, 2017, https://www.cato.org/publications/tax-budget-bulletin/low-income-housing-tax-credit-costly-complex-corruption-prone (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Ed Olsen, “Does Housing Affordability Argue for Subsidizing the Construction of Tax Credit Projects?” March 24, 2017, revised July 26, 2017, prepared for presentation at a conference on housing affordability at the American Enterprise Institute, April 6, 2017, http://eoolsen.weebly.com/uploads/7/7/9/6/7796901/olsenaeihousingaffordabilityconferencepanel12rev.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Michael D. Eriksen, “The Market Price of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2 (September 2009), pp. 141–149.

- Scott Eastman and Nicole Keading, “Opportunity Zones: What We Know and What We Don’t,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 630, January 8, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/opportunity-zones-what-we-know-and-what-we-dont/ (accessed March 25, 2019); [Name redacted on web site], “Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Communities, and Renewal Communities: Comparative Overview and Analysis,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, February 14, 2011, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20110214_R41639_b18ae5bf0fbe93505d7b6c2b13b744b76124b9ed.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- A census tract is a geographic area designated for the purpose of taking the census.

- 26 U.S. Code § 45D—New Markets Tax Credit, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/45D (accessed March 22, 2019); Donald J. Marples and Sean Lowry, “New Markets Tax Credit: An Introduction,” August 31, 2016, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34402.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 26 U.S. Code §§ 1391–1397, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/subtitle-A/chapter-1/subchapter-U (accessed March 22, 2019); [Name redacted on web site], “Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Communities, and Renewal Communities: Comparative Overview and Analysis.”

- 26 U.S. Code § 45A—Indian Employment Credit, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/45A (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Richard Rubin, “If the Tax Overhaul Smells Fishy, It’s Probably the Samoan Tuna Plant,” The Wall Street Journal, November 28, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/if-the-tax-overhaul-smells-fishy-its-probably-the-samoan-tuna-plant-1511813469 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- This phenomenon has been documented in the research and development tax credit. See Bronwyn Hall and John Van Reenen, “How Effective Are Fiscal Incentives for R&D? A Review of the Evidence,” Research Policy, Vol. 29, Nos. 4–5 (April 2000), pp. 449–469, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~bhhall/papers/HallVanReenan%20RP00.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Olivier Wellman-Labadie and Youwen Zhou, “The US Orphan Drug Act: Rare Disease Research Stimulator or Commercial Opportunity?” Health Policy, Vol. 95, Nos. 2–3 (May 2010), pp. 216–228.

- Ibid.

- Rachel Greszler, “Paid Family Leave: Avoiding a New National Entitlement,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3231, July 20, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/report/paid-family-leave-avoiding-new-national-entitlement; Joint Committee on Taxation, U.S. Congress, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, the ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’: Fiscal Years 2018–2027,” JCT-67-17, December 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Harald Dale-Olsen, “Wages, Fringe Benefits and Worker Turnover,” Labour Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1 (February 2006), pp. 87–105.

- H.R.2264, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, Public Law 103-66, 103rd Cong., August 10, 1993, https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/2264 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2016 Revenue Proposals, February 2015, p. 122, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/documents/general-explanations-fy2016.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 26 U.S. Code § 45G—Railroad Track Maintenance Credit, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/45G (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Congressional Budget Office, “H.R. 88, Retirement, Savings, and Other Tax Relief Act of 2018 and Taxpayer First Act of 2018, as Amended by the House Committee on Rules on November 28, 2018,” Cost Estimate, December 7, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2018-12/hr88.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- 26 U.S. Code § 47—Rehabilitation Credit, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/47 (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Emily Hamilton, “Historic Preservation: Bad for Neighborhood Diversity,” Market Urbanism, September 4, 2014, http://marketurbanism.com/2014/09/04/historic-preservation-bad-for-neighborhood-diversity/ (accessed March 22, 2019).

- H.R. 3448, Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996, P.L. 104-188, 104th Cong., August 20, 1996, https://www.congress.gov/104/plaws/publ188/PLAW-104publ188.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019); Benjamin Collins and Sarah A. Donovan, “The Work Opportunity Tax Credit,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress, updated September 25, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43729.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- It was required that eligible wages be paid after the disaster and before January 1, 2018.

- S. 933, Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Public Law 101-336, 101st Cong., July 26, 1990, http://library.clerk.house.gov/reference-files/PPL_101_336_AmericansWithDisabilities.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Daron Acemoglu and Joshua D. Angrist, “Consequences of Employment Protection? The Case of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 109, No. 5 (October 2001), pp. 915–957, https://economics.mit.edu/files/17 (accessed March 22, 2019).