Successive American presidential Administrations, guided by the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, have recognized that a Taiwan that is free to make its own decisions, free from coercion by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), is in the vital national security interest of the United States. The Taiwan Relations Act, in fact, is explicit about the connection between Taiwan’s fate and the maintenance of “peace, security and stability in the Western Pacific.”[1]

A failure to meet this requirement, thereby allowing Taiwan to be coerced into a closer relationship with China, would be a devastating blow to regional confidence in American leadership as well as the peace, security, and prosperity of the region.

The extent to which the U.S. is effectively meeting Taiwan’s security requirements as outlined by the Taiwan Relations Act is a matter of intense debate. Given less attention in Washington, however, is China’s growing economic clout with Taiwan, and what the U.S. can do to blunt its potential coercive power.

In 2000, total trade between Taiwan and China (including Hong Kong) was only $18.5 billion.[2] By 2013, it had grown to over $165 billion, representing a compound annual growth rate of over 18 percent. China is now Taiwan’s largest trading partner, accounting for 40 percent of Taiwan’s exports.

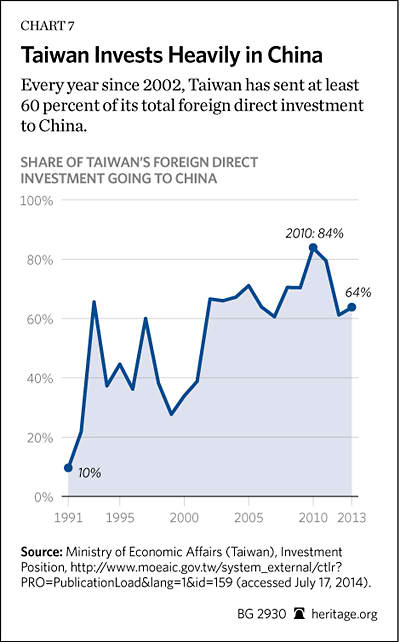

Taiwan has also grown dependent on China for its outward-bound foreign direct investment (FDI). Amounting to only $174 million in 1991, Taiwan’s investment flows into China peaked at approximately $14 billion in both 2010 and 2011. Over this same period, the weight of China in Taiwan’s total outward-bound investment increased from 10 percent to a high of 84 percent in 2010.

The composition of Taiwan’s investment in China has also transformed from labor-intensive industries led by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to high-technology sectors led by large enterprises.[3] Taiwan’s massive investment in manufacturing sectors in China has coincided with its de-industrialization over the past decade.

Largely locked out of the free trade agreements (FTAs) proliferating across Asia, Taiwan is quickly becoming ever more economically dependent on China. Accession to regional economic agreements and economic liberalization would allow Taiwan to create a more diverse, flexible network of economic relationships and fully operationalize its economy’s comparative advantages.

Taiwan’s Relative Economic Decline

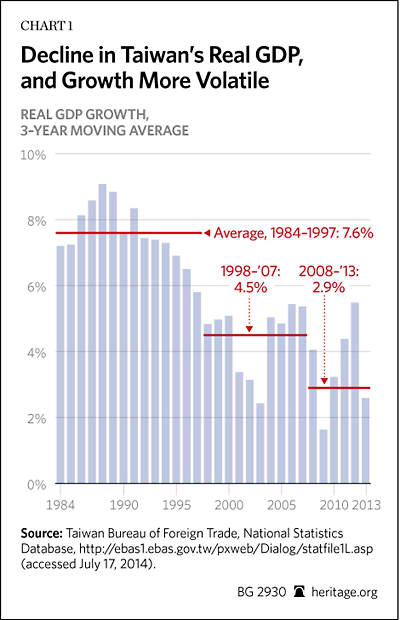

Taiwan has experienced a sharp deceleration in economic growth since the late 1980s and early 1990s when it was averaging lofty growth rates in the high single digits. As Chart 1 illustrates, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth not only decelerated rapidly but also increased in volatility (even with a three-year moving average).

Some of this decline was inevitable given Taiwan’s affluence. It has one of the highest average annual household incomes[4] in the region and a per capita GDP of almost $39,000 measured in purchasing power parity ($21,000 at current exchange rates).[5] That said, Taiwan’s real GDP growth has fallen below expectations in recent years, with growth averaging 5.2 percent from 2002 to 2007, to just 2.9 percent from 2008 to 2013. It has only averaged 2.6 percent during the past three years.

At first glance, the slower economic growth could simply be attributed to a slower post-recession global economy. With exports accounting for approximately 60 to 70 percent of GDP in recent years, Taiwan does remain an export-oriented economy. Closer observation, however, shows that its slower growth cannot be solely attributed to trends in the global economy.

In 2013, the service sector accounted for 69 percent of Taiwan’s GDP while the industry and agricultural sectors accounted for 29 percent and 2 percent, respectively.[6] This is significantly different from the late 1980s when industry accounted for approximately 40 percent of Taiwan’s economy.

While a transition to a service-based economy is a natural progression as economies mature, in Taiwan’s case, the service sector has become Taiwan’s Achilles’ heel. Plagued by low productivity, the country’s service sectors are largely small in scale and domestically oriented. This is in contrast to Singapore and Hong Kong where internationally competitive service sectors have contributed significantly to their economic development.

Moreover, looking toward the future, because so much manufacturing has moved from Taiwan to China, the service industry that supports manufacturing could also move offshore to China in order to be better able to respond to Chinese domestic demand and local economic conditions. China could become more than a basic-components assembler of manufactured goods and transform into a comprehensive supply chain that includes sales and aftermarket services.

Taiwan’s business environment is also facing increased competition from its neighbors in the region. Taiwan ranks a very respectable 16th in the World Bank’s 2014 Doing Business report, but it is scoring below regional competitors, such as Singapore (1st), Hong Kong (2nd), Malaysia (6th), and Korea (7th).[7] During the 1980s, rising labor costs and the appreciation of the Taiwanese dollar were often cited as reasons for Taiwan’s inability to attract foreign businesses relative to their regional peers. Today, however, bureaucratic hurdles, an uncompetitive tax system, weak protection for investors, weak contract enforcements, and relatively poor regional economic integration are believed to be responsible for Taiwan’s lackluster foreign direct investment.

Taiwanese World Trade. As an export-oriented economy, Taiwan has been dependent on external trade to sustain its economic development. The total value of trade increased more than fivefold in the 1960s, nearly tenfold in the 1970s, and then doubled in the 1980s before almost doubling again during the 1990s. In 2013, Taiwanese total trade summed to $574 billion ($305 billion and $269 billion of exports and imports, respectively) or 118 percent of GDP at current exchange rates.[8]

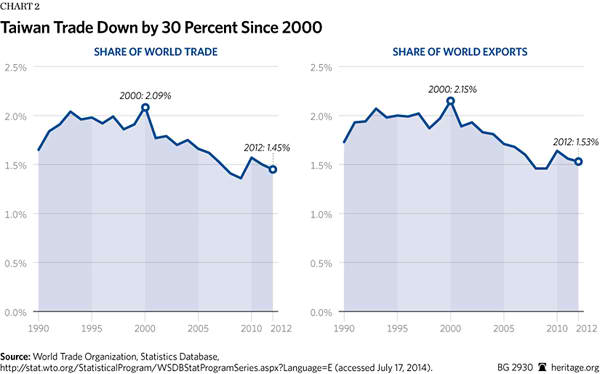

While many of its neighbors’ shares of world trade have risen in recent years, Taiwan’s has declined, suggesting a possible loss in competitiveness.

Taiwan’s global share of world trade and global exports peaked in 2000 at 2.1 percent and 2.2 percent, respectively. By 2012, these shares had fallen to 1.45 percent and 1.5 percent. While seemingly small, this represents a 30 percent decline in Taiwan’s share of world trade over the past decade.

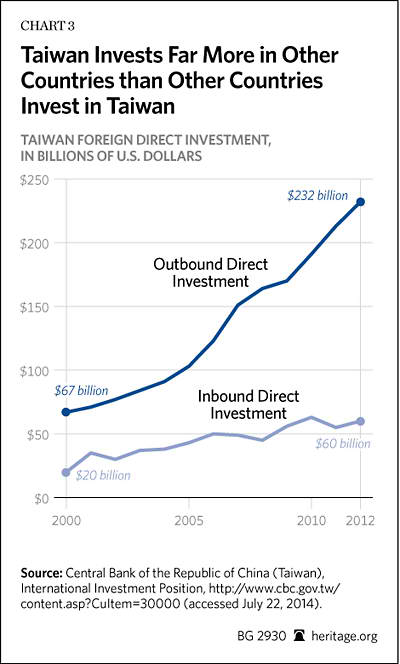

Foreign Direct Investment. The “deindustrialization” of Taiwan is exemplified by the growing disparity between inbound and outbound FDI. With the exception of the semiconductor industry, which continues its investment in R&D and capital equipment for its expansion in high-end production, most of Taiwan’s manufacturing firms have cut their investments at home.[9]

Since 1997, Taiwan’s inbound investment has been consistently less than outbound investment. Between 2000 and 2012, Taiwan’s outbound investment amounted to $165 billion, more than four times the level of inbound investment ($40 billion).

In 2012, Taiwan’s stock of inbound FDI was valued at almost $60 billion—not much more than the $50 billion in 2006. In 2012, FDI flows into Taiwan were $4.7 billion, while they were over $16 billion for Korea, its closest competitor.

Taiwan has also attracted minuscule private equity capital in recent years, depriving the most active channels of investment capital and managerial expertise.

Demographics—Ever Shrinking. Taiwan’s demographic profile is not advantageous for faster economic growth. By 2025, people over age 65 will make up one-fifth of the total population. Meanwhile, Taiwan has historically low fertility rates. It reached its lowest level in 2010 with 0.90 children per female. In 2012 it was 1.3 children.[10]

This trend has made Taiwan one of the fastest-aging countries in the world. The working-age population is set to decline from 2015 after reaching a peak of 17.3 million. The dependence ratio, currently 35 percent, is expected to rise to 53 percent in 2030, and 80 percent by mid-century.[11]

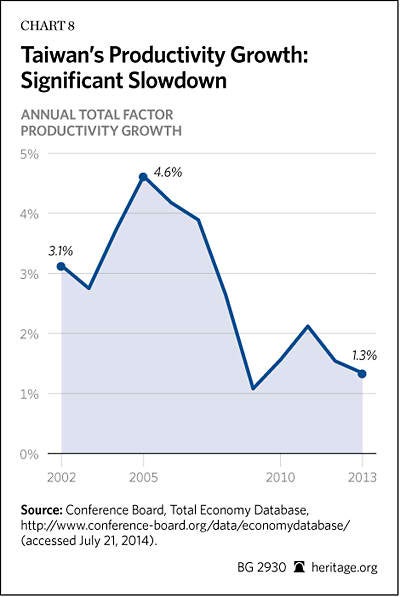

Due to its aging profile, it is estimated that Taiwan’s total population will fall from the current 23 million to 19 million by mid-century. Taiwan’s demographic deficit will deeply diminish the nation’s economic prospects. A shrinking workforce will most certainly rob Taiwan of the human capital it will need in the coming decades. The loss of dynamism that young people bring to a modern economy is virtually incalculable. Taiwan will claim fewer patents, start fewer businesses, and produce fewer artistic achievements. Moreover, with a shrinking workforce, all economic growth must be generated by productivity gains, which have weakened in recent years.

China’s Economic Vassal?

Taiwan’s Growing Economic Interdependence with China. Over the course of a relatively short period, there has been a radical shift in Taiwan’s trade and investment destinations. In 2000, total trade with China (including Hong Kong) was only $18.5 billion. By 2013, total trade with China had grown to over $165 billion ($121 billion in exports to China and $44 billion in imports from China). China is now Taiwan’s biggest trading partner, accounting for 40 percent of Taiwan’s exports and 16 percent of Taiwan’s imports (2013 figures).

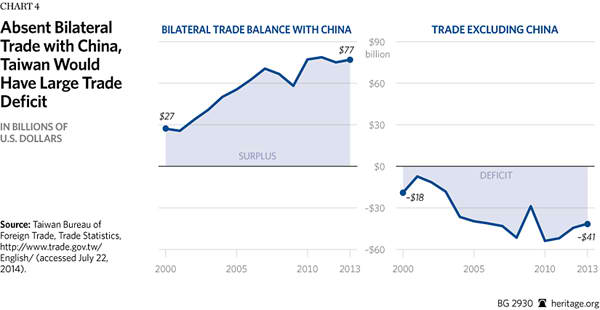

Thanks in part to the enormous differences in size between the two countries, Taiwan has run large trade surpluses with China. Although the surpluses have leveled off, they remain sizable. The $77 billion bilateral surplus with China in 2013 was larger than the $37 billion total surplus in the same year. In other words, with the rest of the world, Taiwan now runs a trade deficit.

Over the same period, Taiwan’s trade relations with the United States moved just as significantly in the opposite direction. In 2000, two-way trade with the United States totaled 41 percent (23 percent of Taiwan’s exports) of Taiwanese total trade. By 2013, total trade with the United States had dropped by roughly half, totaling 21 percent (11 percent of Taiwan’s exports) of Taiwanese total trade.[12]

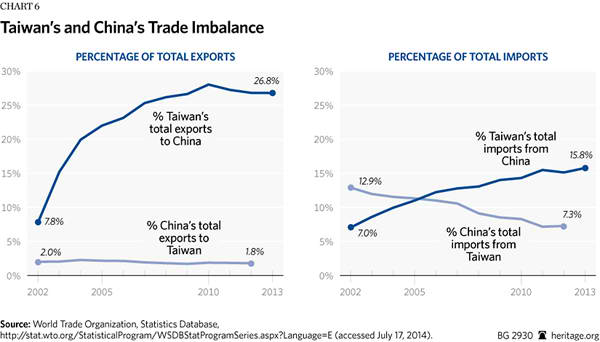

Another way to examine how two-way trade has changed is to compare the trade shares relative to each other’s total trade. Here, the relationship has become asymmetrical. While China has become increasingly important in Taiwan’s external trade, Taiwan’s importance in China’s overall trade is decreasing.

From 2000 to 2013, China’s exports to Taiwan remained fairly steady at around 2 percent of total Chinese exports. The lack of growth in Chinese exports to Taiwan as a share of its total indicates that Taiwan’s small market is currently providing only limited potential for China’s products.

On the other hand, China has become a critical market for Taiwan’s exports, with its share rising fourfold (to 27 percent) over the past decade, although it has leveled off.

Meanwhile, China’s imports from Taiwan as a percentage of its total imports have declined from 13 percent to 7 percent (for 2012), while Taiwan’s import share from China rose to 16 percent by 2013.

According to Min-hua Chiang, a researcher at the East Asian Institute,[13] there are three important reasons why Taiwan is experiencing a falling market for Chinese imports. The first is rising labor and land costs in China. Many Taiwanese companies in China are under cost pressures and have reduced their imports of intermediate goods from Taiwan.

Second, in recent years, many of the mainland-based Taiwanese companies have shifted their preferences for purchasing intermediate goods from China instead of importing them from Taiwan. In 2002, only 15 percent of mainland-based Taiwanese companies procured capital equipment and intermediate goods from local firms in China, but this ratio increased to over 60 percent in 2010.

Third, Taiwan’s falling share in China’s total imports may also be a result of China’s changing overall import structure. China’s import share of mineral products increased from 8 percent in 2002 to 25 percent in 2011, while its imports of machinery (from 43 percent to 32 percent) and electrical equipment (from 25 percent to 20 percent) had decreased. This changing import structure from industrial goods to mineral products implies that if China’s economy continues to move up the value chain, the demand for intermediate goods from Taiwan will continue to diminish.

This trend in two-way trade is not likely to reverse anytime soon. The Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) of 2010 has the potential to open up the vast Chinese market to Taiwan businesses. The economic accord and its constituent agreements are the most significant between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait since the founding of the PRC in 1949. Negotiations continue about follow-on components of the ECFA regarding trade in goods and a dispute resolution mechanism.

Unfortunately, the ECFA also has the potential, over time, to make Taiwan even more dependent on the Chinese market unless Taiwan starts diversifying the destination of its exports by signing FTAs with other nations.

One of the agreements derivative of the ECFA, the Cross-Strait Services Agreement, is a subject of intense controversy in Taiwan and there are some questions whether and in what time frame it will be ratified. Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement protested the treaty in Taiwan’s Parliament during March 2014, in what was the largest student protest in the history of Taiwan. Advocates of the treaty believe it would provide Taiwan’s economy a boost, which it desperately needs. Critics of the treaty are mostly concerned with China’s growing power over Taiwan and the impact that power could have on small and medium-sized Taiwanese enterprises.

This structural shift in two-way trade obviously has both serious political and economic repercussions. If nothing is done to open up alternative patterns of economic activity for Taiwan, China will potentially have enormous leverage over Taiwan.

There is an additional equally obvious economic risk to Taiwan becoming so reliant on the Chinese market. While China avoided a recession during the 2008–2009 financial crisis with an enormous stimulus package, a “hard landing” would have a major negative impact on Taiwan’s exports to China and economic growth at a time when Taiwan’s economy has already slowed down considerably.

Taiwan’s Shifting Investment in China. This increased economic interdependence between China and Taiwan is not limited to two-way trade. When Taiwan lifted its ban on indirect investment in China, the mainland quickly became the most important recipient for Taiwan’s outward FDI.

China’s total outbound FDI has increased from almost nothing in 2000 to $90 billion in 2013. Despite their close economic ties, however, Taiwan is not getting much from the mainland by way of investment. The trifling inflow of Chinese investments so far is largely because Taiwan’s small market holds no interest for China’s giant state-owned enterprises. Moreover, the Taiwanese high-technology sector, which would be of great interest for Chinese investors, is still regulated and closed off.

Amounting to only $174 million in 1991, this figure peaked at $14 billion in both 2010 and 2011. (It has fallen in recent years as Chinese labor costs have increased significantly, making the mainland less appealing for Taiwanese manufacturers.) Over the same period, the weight of China in Taiwan’s total outward investment increased from 10 percent to a high of 84 percent in 2010. Most of Taiwan’s investment is in the manufacturing sector with electronic parts, computer electronics, and optical manufacturing possessing the largest shares.

These investment levels have made China central to the supply chains of Taiwanese manufacturers. They have also generated a high volume of trade between Taiwanese businesses located in China and Taiwan. As a consequence, the lion’s share of Taiwan–China trade falls within the same sectors as Taiwanese outbound investment in China.

Since the ECFA came into effect, approved Chinese investment in Taiwan has increased from $94 million in 2010 to $328 million in 2012. Supporters of the ECFA hope that the trade agreement will serve as a gateway for investment from China.

While Taiwan has its own currency, there is early evidence of increased acceptability of the Chinese renminbi. In 2012, Taiwan’s Central Bank signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on cross-Strait currency settlement with its Chinese counterpart. The MOU allows the direct settlement of the Chinese renminbi and the Taiwan dollar across the Taiwan Strait, which could help develop Taiwan into a local renminbi hub.

Asia’s Regional Economic Integration

Some of the beneficial effects of regional economic integration are the following:[14]

- A regional common market provides a much larger market than that offered by the domestic market of a single country, so economies of scale become possible.

- The larger market created would permit a higher degree of specialization. This would encourage the flow of investment into industries that have a comparative cost advantage, producing greater gains from trade.

- The increased possibilities of competition in a regional common market would ensure that many of the benefits accruing to the producers from the existence of a large market would be passed on to the consumer.

Asia’s movement toward FTAs began taking off last decade as the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Doha round of trade negotiations unraveled and as the U.S. began negotiating FTAs. As a result, according to the Asian Development Bank, as of April 2014, ratified FTAs involving an Asian country numbered 113, up from 36 in 2002. Twenty-two have been signed but are not yet in effect, and 62 are under negotiation.[15] In addition, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) hopes to create a single-market with free movement of goods, services, and investments throughout the 10 ASEAN nations by the end of 2015.

Taiwan has been almost completely absent from this proliferation of Asian FTAs. Initially, Taiwan only managed to negotiate FTAs with its “diplomatic allies” in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. In 2013, these four Central American nations combined represented 0.001 percent of Taiwan’s exports. Only in 2013 did Taiwan conclude FTAs with two countries that do not recognize it diplomatically, New Zealand and Singapore. (Singapore is a much larger trading partner, importing 6 percent of Taiwan’s exports.) While Taiwan joined the WTO in January 2002 (shortly after China’s entry), the growing global trade that is now subject to preferential treatment under FTAs is undermining the value of its WTO membership.[16]

Left out, Taiwan will be harmed by the FTAs’ trade-diversion effect as Taiwan’s exports lose out in FTA markets due to increased competition from imports from other FTA partners. The successful completion by Korea—a competitor with Taiwan across a wide range of products—of FTAs with the European Union and United States provides a useful example of some of the costs to Taiwan of not participating in these Asian FTAs. (In total, Korea has managed to sign eight FTAs covering 46 countries.) As a result, Korean goods now have preferential access to the two largest developed country markets where all tariffs will eventually fall to zero while Taiwanese exports in many cases will face double-digit duties.[17]

This pattern of moving toward China-centric regionalization could have debilitating effects on Taiwan.[18] The inability of Taiwan to participate in FTAs is creating an incentive for Taiwanese businesses to invest in other Asian countries and therefore take advantage of the tariff preference for exports from these countries to other FTA parties. This ongoing process of economic isolation from the rest of the world could undermine investors’ confidence in Taiwan’s economic prospects, and discourage domestic and foreign direct investments in Taiwan—at a time when it needs more investment and research and development to diversify its exports and move to higher value-added goods and services to tackle the challenges of slower economic growth.

What Can be Done? A Market Solution for Taiwan

Economically, since 2000, times have not been good for Taiwan. This is for two primary reasons. First, lackluster economic growth has set in and is beginning to look increasingly permanent in nature. Second, in a relatively short period of time, Taiwan has become deeply dependent on the Chinese market for its exports and investments. This is a serious problem because China’s ultimate end-goal with Taiwan is not economic in nature but largely political. That goal, of course, is the unification of Taiwan with the People’s Republic of China. In the context of an extremely unbalanced economic relationship, it does not take much imagination to predict who will dominate the relationship. One thing is certain: The United States cannot stand idly by unless it wants to lose Taiwan as a security partner and democratic beacon in Asia that is able to determine the nature of its relationship with China according to its own political processes. While current economic trends may lend themselves to a bleak outlook on Taiwan’s autonomy, however, the market may provide a solution.

What Taiwan Needs to Do. The economic reforms required by entry into the WTO in early 2002 boosted Taiwan’s productivity and economic growth. Under the terms of its WTO accession, Taiwan agreed to cut tariffs and non-tariff barriers on a wide range of goods, completely open a number of service sectors, and increase protection for intellectual property rights. Since that time, however, with multilateral trade liberalization dormant (that is, the Doha round), and having little ability to participate in FTAs, economic reforms in Taiwan have stalled, and the efficiency gains from early last decade have dissipated.

Taiwan’s current simple average tariff rate is only 6.3 percent, although non-tariff barriers are still prevalent (for manufacturing goods the simple average tariff is only 3.2 percent).[19] As a consequence, FTAs by themselves, will not be the cure for Taiwan’s ailing economy. What Taiwan critically needs is a domestic reform agenda with a strong free-market disposition. This agenda should include the following:

- Production mix of software and software services. Taiwan is one of the global leaders in information technology (IT) supply chains that cover everything from microchips to mobile phones. IT products account for approximately 40 percent of Taiwan’s exports. Of Taiwan’s IT production, approximately 70 percent is hardware and 30 percent software (in most developed countries this ratio is reversed). There are two problems with this status quo. First, IT hardware is being increasingly produced elsewhere, particularly in China. Second, software and services generally enjoy larger profit margins than manufacturing and generate more jobs and economic growth. While software and services can also be imported, they possess a stronger domestic bias. A greater emphasis on IT software R&D will be vital to developing the local software and service industries.

- Low-cost energy. Cheap energy is a critical input for stronger economic growth. Taiwan’s ability to meet future demand looks uncertain. Strong opposition to its fourth nuclear power plant has raised doubt that it will ever be used, removing a significant source of power capacity from future supply—nuclear power provides 19 percent of Taiwan’s power generation, half the level of two decades ago. All other options are less appealing. Renewable energy sources will not provide enough energy, and liquefied natural gas is expensive. As recommended by the American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei,[20] Taiwan would be wise to employ a balanced combination of energy sources, including nuclear and renewables. Since it can take up to a decade to design and build a power plant, Taiwan should resolve this issue quickly.

- Improved competitiveness. As discussed, Taiwan does not rank well compared to its regional neighbors as a competitive place to do business. In The Heritage Foundation’s 2014 Index of Economic Freedom, co-published with The Wall Street Journal, it scores a very respectable 17th of 186 countries. It scores poorly in labor freedom (126th), however, given that the labor market lacks flexibility. Similarly, in the World Bank’s 2014 Doing Business survey, Taiwan is ranked 16th overall but it scores poorly in the categories of “getting credit” (73rd), “paying taxes” (58th), and “enforcing contracts” (84th).[21] Stagnant wages in recent years have been leading to a brain drain to competing centers of excellence, such as Hong Kong and Singapore.[22]

- Investor protection. Taiwan must do a better job of protecting investors. In the Index of Economic Freedom’s “financial freedom” rankings, Taiwan is only ranked 41[st]. (Hong Kong is ranked first and Singapore fourth.) According to the World Bank’s 2013 Index of Investor Protection, Taiwan is ranked 34th in the world for investor protection. While that is not a poor ranking by global standards (there are 189 countries in the index), Taiwan scores very poorly compared to other East Asian countries. For example, in the World Bank’s index, Singapore is rated second in the world in protecting investors, Hong Kong third, Malaysia a surprising fourth, and Thailand 12[th]. (South Korea is ranked 52nd.) Of the three dimensions of investor protection, Taiwan scores well on the requirements regarding the approval and disclosure of related party transactions, but has mediocre scores for the liability of the CEO and board of directors in related party transactions and the ease with which shareholders can file a lawsuit against the company.

- Rebalanced growth. Taiwanese authorities should also actively seek to reduce Taiwan’s reliance on trade as an engine of growth by increasing domestic consumption and encouraging greater private-sector investment in Taiwan. This includes encouraging Taiwanese firms to invest in Taiwan instead of overseas (mostly China) and greater FDI inflows into Taiwan. Foreign businesses bring in new technology and skills that accelerate innovation and economic growth.

- Consumer-protection laws. Well-intentioned but impractical initiatives in consumer protections are damaging Taiwan’s attractiveness to business without much actual benefit to consumers. These laws need to be scaled back or eliminated.

- More transparent investment process. The level of private-equity engagement in Taiwan has been among the lowest in Asia in recent years. The foreign-investment approval process needs to be made more transparent, predictable, and efficient.

- More inward FDI. Participation in FTAs would also further Taiwan’s goal of increasing inward FDI. As discussed, comprehensive FTAs include commitments to liberalize investment restrictions and include rules on investment protection. Such action should lead to increased FDI into Taiwan. In 2014, Taiwan was only ranked 46th in investment freedom in the Index of Economic Freedom.

- Regional FTAs. Taiwan has explored FTAs with India, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Taiwan should attempt to hammer out separate agreements before the national election in 2016.

- End ban on U.S. pork and beef imports. Taiwan should eliminate its ban on U.S. pork and some beef imports which contain the leanness-enhancing drug ractopamine. The ban has been a major source of contention with the United States for some time now and jeopardizes a future FTA with the U.S. It also casts doubt on Taiwan’s commitment to science-based regulatory standards more generally.

- More Taiwanese. Taiwan’s government needs to make an effort to boost its dangerously low birth rate; otherwise, Taiwan’s economy in the region will likely be marginalized by its shrinking population. Beijing will soon have a larger population than the entirety of Taiwan.

What the U.S. Needs to Do. The U.S. can do the following to help guide Taiwan through the trade liberalization process, including its entry into the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

- In addition to guiding trade negotiators toward genuine trade liberalization, any Trade Promotion Authority approved by Congress should be applicable to a bilateral free trade agreement with Taiwan.

- The U.S. should launch negotiations on a Bilateral Investment Agreement with Taiwan. An agreement would position the U.S. to support Taiwan’s eventual membership in the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The United States should assist Taiwan in making the necessary structural adjustments so it can progress toward TPP standards. The 12 member nations of the TPP, which currently account for 38 percent of global GDP and 25 percent of world trade, offer Taiwan the opportunity to diversify and rebalance its external economic relations. TPP membership would provide Taiwan with a strong external stimulus and vehicle to carry out structural reforms and rebuild people’s confidence in Taiwan’s economic prospects. Market liberalization and economic confidence will be conducive to investments that are critical to Taiwan’s long-term economic competitiveness.

Conclusion

Taiwan is at a crossroad. During much of the Cold War, Taiwan depended on the United States to export its way toward economic development and prosperity. Within a relatively short period of time, that relationship has been supplanted by China.

This has put Taiwan in a precarious position. Being overly dependent on the Chinese economy means that Taiwan’s fate could largely be determined by economic conditions in China and political decisions made in Beijing.

While much of Asia has been rapidly integrating in recent years through FTAs, Taiwan has been left out in the cold. The political isolationism that Taiwan has endured has eventually produced a similar degree of economic isolationism.

The result has been deterioration of Taiwan’s economic fundamentals—such as slower economic and productivity growth, over-reliance on one trading partner, and stagnating wages. While Taiwan remains a wealthy high-tech exporting giant, large cracks are appearing in its gleaming exterior.

Taiwan’s economic status quo is not sustainable; it can be changed with the right combination of policies. The United States should publically encourage Taiwan’s bilateral and multilateral ambitions. Signing a bilateral investment agreement with the U.S. would be a good step toward Taiwan eventually joining the TPP. The domestic economic reforms described here would help resuscitate Taiwan’s economy and provide invaluable support to stability and peace in cross-Strait relations. It would also revitalize U.S. relations with a vital strategic partner in the Pacific.

—William T. Wilson, PhD, is a senior research fellow in the Asian Studies Center, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation.