Six years ago, President Bill Clinton signed legislation overhauling part of the nation's welfare system. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-193) replaced the failed social program known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) with a new program called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). The reform legislation had three goals: (1) to reduce welfare dependence and increase employment; (2) to reduce child poverty; and (3) to reduce illegitimacy and strengthen marriage.

At the time of its enactment, liberal groups passionately denounced the welfare reform legislation, predicting that it would result in substantial increases in poverty, Hunger, and other social ills. Contrary to these alarming forecasts, welfare reform has been effective in meeting each of its goals.

- Overall poverty, child poverty, and black child poverty have all dropped substantially

Although liberals predicted that welfare reform would push an additional 2.6 million persons into poverty, the U.S. Bureau of the Census reports there are 3.5 million fewer people living in poverty today than there were in 1995 (the last year before the reform). - Some 2.9 million fewer children live in poverty today than in 1995

- Decreases in poverty have been greatest among black children

In fact, the poverty rate for black children is now at the lowest point in U.S. history. There are 1.2 million fewer black children in poverty today than there were in the mid-1990s. - Hunger among children has been cut roughly in half

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), there are 420,000 fewer hungry children today than at the time welfare reform was enacted. - welfare caseloads have been cut nearly in half

and employment of the most disadvantaged single mothers has increased from 50 percent to 100 percent. - The explosive growth of out-of-wedlock childbearing has come to a virtual halt

The share of children living in single-mother families has fallen, and the share living in married-couple families has increased, especially among black families.

Some attribute these positive trends to the strong economy in the late 1990s. Although a strong economy contributed to some of these trends, most of the positive changes greatly exceed similar trends that occurred in prior economic expansions. The difference this time is welfare reform.

welfare reform has substantially reduced welfare's rewards for non-work, but much more remains to be done. When TANF is reauthorized next year, federal work requirements should be strengthened to ensure that states require all able-bodied parents to engage in a supervised job search, community service work, or skills training as a condition of receiving aid. Even more important, Congress must recognize that the most effective way to reduce child poverty and increase child well-being is to increase the number of stable, productive marriages. In the future, Congress must take active steps to reduce welfare dependence by rebuilding and strengthening marriage.

PREDICTIONS OF SOCIAL DISASTER DUE TO WELFARE REFORM

Six years ago, when the welfare reform legislation was signed into law, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) proclaimed the new law to be "the most brutal act of social policy since reconstruction."1 He predicted, "Those involved will take this disgrace to their graves."2

Marian Wright Edelman, president of the Children's Defense Fund, declared the new reform law an "outrage...that will hurt and impoverish millions of American children." The reform, she said, "will leave a moral blot on [Clinton's] presidency and on our nation that will never be forgotten."3

The Children's Defense Fund predicted that the reform law would increase

child poverty nationwide by 12 percent...make children hungrier...[and] reduce the incomes of one-fifth of all families with children in the nation.4

The Urban Institute issued a widely cited report predicting that the new law would push 2.6 million people, including 1.1 million children, into poverty. In addition, the study announced the new law would cause one-tenth of all American families, including 8 million families with children, to lose income.5

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities asserted the new law would increase the number of children who are poor and "make many children who are already poor poorer still.... No piece of legislation in U.S. history has increased the severity of poverty so sharply [as the welfare reform will]."6

Patricia Ireland, president of the National Organization for Women, stated that the new welfare law "places 12.8 million people on welfare at risk of sinking further into poverty and homelessness."7

Peter Edelman, husband of Marian Wright Edelman and then Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the Department of Health and Human Services, resigned from the Clinton Administration in protest over the signing of the new welfare law. In an article entitled "The Worst Thing Bill Clinton Has Done," Edelman dubbed the new law "awful" policy that would do "serious injury to American children."8

Peter Edelman believed the reform law would not merely throw millions into poverty, but also would actively worsen virtually every existing social problem. "There will be more malnutrition and more crime, increased infant mortality, and increased drug and alcohol abuse," claimed Edelman. "There will be increased family violence and abuse against children and women." Moreover, the bill would fail even in the simple task of "effectively" promoting work because "there simply are not enough jobs now."9

In the six years since the welfare reform law was enacted, social conditions have changed in exactly the opposite direction from that predicted by liberal policy organizations. As noted above, overall poverty, child poverty, black child poverty, poverty of single mothers, and child Hunger have declined substantially. Employment of single mothers increased dramatically, and welfare rolls plummeted. The share of children living in single-mother families fell, and -- more important -- the share of children living in married-couple families grew, especially among black families.10

Opponents of reform would like to credit many of these positive changes to a "good economy." However, according to their predictions in 1996 and 1997, liberals expected the welfare reform law to have disastrous results during good economic times. They expected reform to increase poverty substantially even during periods of economic growth; if a recession did occur, they expected that far greater increases in poverty than those mentioned above would follow. Thus, it is disingenuous for opponents to argue in retrospect that the good economy was responsible for the frustration of pessimistic forecasts since the predicted dire outcomes were expected to occur even in a strong economy.

Less Poverty

Since the enactment of welfare reform in 1996, the poverty rate has fallen from 13.8 percent in 1995 to 11.7 percent in 2001. Liberals predicted that welfare reform would push an additional 2.6 million people into poverty, but there are actually 3.5 million fewer people living in poverty today than there were when the welfare reform law was enacted.11

Less Child poverty

The child poverty rate has fallen from 20.8 percent in 1995 to 16.3 percent in 2001. In 1995, there were 14.6 million children in poverty compared with 11.7 million in 2001. Though liberals predicted that welfare reform would throw more than 1 million additional children into poverty, there are some 2.9 million fewer children living in poverty today than there were when welfare reform was enacted.12

Less Black Child poverty

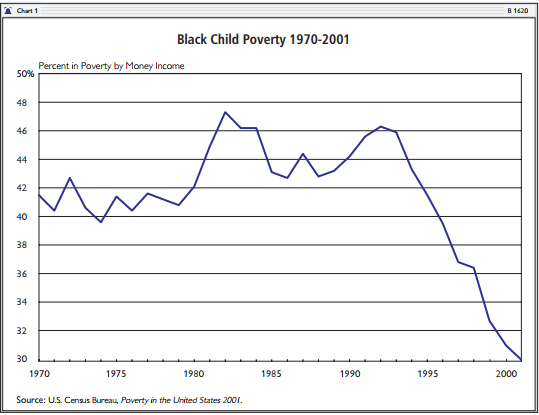

The decline in poverty since welfare reform has been particularly dramatic among black children. As Chart 1 shows, for a quarter-century prior to welfare reform, there was little change in black child poverty. Black child poverty was actually higher in 1995 (41.5 percent) than in 1971 (40.4 percent).

With the enactment of welfare reform in 1996, black child poverty plummeted at an unprecedented rate, falling by more than a quarter to 30.0 percent in 2001. Over a six-year period after welfare reform, 1.2 million black children were lifted out of poverty. In 2001, despite the recession, the poverty rate for black children was at the lowest point in national history.13

Less Poverty Among Children of Single Mothers

Since the enactment of welfare reform, the drop in child poverty among children in single-mother families has been equally dramatic. For a quarter-century before welfare reform, there was little net decline in poverty in this group. poverty was only slightly lower in 1995 (50.3 percent) than it had been in 1971 (53.1 percent). After the enactment of welfare reform, the poverty rate for children of single mothers fell at a dramatic rate, from 50.3 percent in 1995 to 39.8 percent in 2001. In 2001, despite the recession, the poverty rate for children in single-mother families was at the lowest point in U.S. history.14

Dramatic Reduction in Child Hunger

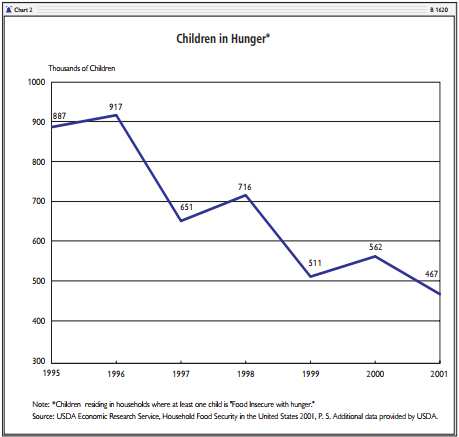

The number of children who are "hungry" has been cut roughly in half since the enactment of welfare reform, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The USDA reports that in 1995, the year before welfare reform was enacted, 887,000 children were hungry; by 2001, the number had fallen to 467,000.15 In percentage terms, the numbers fell from 1.3 percent of children in 1995 to 0.6 percent in 2001. Overall, there are more than 400,000 fewer hungry children today than at the time welfare reform was enacted. (See Chart 2.)

Decrease in "Severe poverty"

Liberals predicted that welfare reform would increase "the severity of poverty." However, the number of children living in "deep poverty" has declined appreciably. (Families in "deep poverty" have incomes that are less than half the poverty income level.) In 1995, there were 5.9 million children living in deep poverty; by 2001, the number had fallen to 5.1 million.16

Plummeting Welfare Dependence

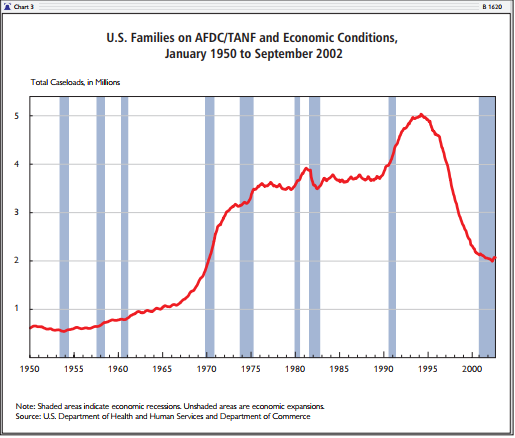

The designers of welfare reform were concerned that prolonged welfare dependence had negative effects on the development of children. Their goal was to disrupt inter-generational dependence by moving families with children off the welfare rolls through increased work and marriage. Since the enactment of welfare reform, welfare dependence has been cut by more than half. The caseload in the former AFDC (now TANF) program has fallen from 4.3 million families in August 1996 to 2.02 million in September 2002. (See Chart 3.)

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the decline in welfare dependence has been greatest among the most disadvantaged and least employable single mothers -- the group with the greatest tendency toward long-term dependence. Specifically, dependence has fallen most sharply among young never-married mothers who have low levels of education and young children.17This is dramatic confirmation that welfare reform is affecting the whole welfare caseload, not merely the most employable mothers.

Strikingly, the TANF caseload has continued to decline even during the current recession. The caseload has fallen from 2.109 million families in April 2001 at the beginning of the recession to 2.017 million in September 2002 (the most recently measured month). This represents a net decline in caseload of 4.4 percent since the beginning of the recession. The continuing decline in welfare dependence during the recession stands in sharp contrast to the 30 percent growth in the AFDC caseload during the economic slowdown of the early 1990s.

Increased Employment

Since the mid-1990s, the employment rate of single mothers has increased dramatically. Again, contrary to conventional wisdom, employment has increased most rapidly among the most disadvantaged, least employable groups:

- Employment of never-married mothers has increased nearly 50 percent.

- Employment of single mothers who are high school dropouts has risen by two-thirds.

- Employment of young single mothers (ages 18 to 24) has nearly doubled.18

Thus, against conventional wisdom, the effects of welfare reform have been the greatest among the most disadvantaged single parents -- those with the greatest barriers to self-sufficiency. Both decreases in dependence and increases in employment have been most dramatic among those who have the greatest tendency to long-term dependence; that is, among the younger never-married mothers with little education.

A Halt in the Rise of Out-of-Wedlock Childbearing

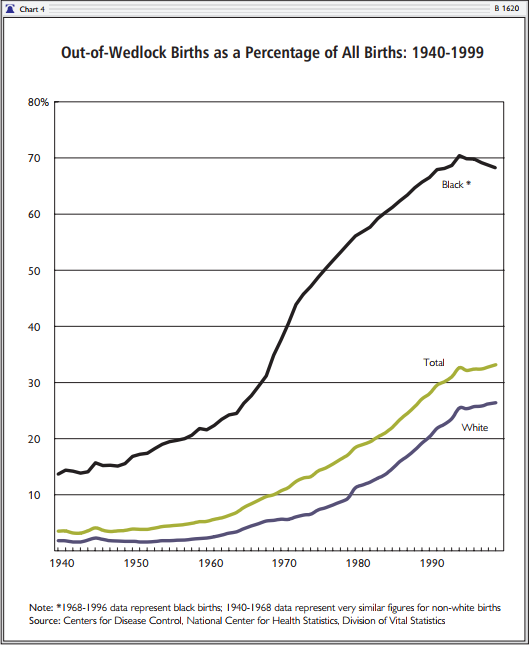

After the beginning of the War on poverty, the illegitimacy rate (the percentage of births outside of marriage) increased enormously. For nearly three decades, out-of-wedlock births as a share of all births rose steadily at a rate of almost one percentage point per year. Overall, out-of-wedlock births rose from 7.7 percent of all births in 1965 to an astonishing 32.6 percent in 1994. However, in the mid-1990s, the relentless 30-year rise in illegitimacy came to an abrupt halt. For the past five years, the out-of-wedlock birth rate has remained essentially flat. (See Chart 4.)

Among blacks, the out-of-wedlock birth rate actually fell from 70.4 percent in 1994 to 68.8 percent in 1999. Among whites, the rate rose slightly, from 25.5 percent to 26.7 percent, but the rate of increase was far slower than it had been in the period prior to welfare reform.

A Shift Toward Marriage

Throughout the War on poverty period, marriage eroded. However, since the welfare reform was enacted, this negative trend has begun to reverse. The share of children living with single mothers has declined, while the share living with married couples has increased.

This change is most pronounced among blacks. Between 1994 and 1999, the share of black children living with single mothers fell from 47.1 percent to 43.1 percent, while the share living with married couples rose from 34.8 percent to 38.9 percent. Similar though smaller shifts occurred among Hispanics.19

While these changes are small, they do represent a distinct reversal of the prevailing negative trends of the past four decades. If these shifts toward marriage are harbingers of future social trends, they are the most positive and significant news in all of welfare reform.

WHO GETS THE CREDIT? THE GOOD ECONOMY VERSUS WELFARE REFORM

Some would argue that the positive effects noted above are the product of the robust economy during the 1990s rather than the results of welfare reform. However, the evidence supporting an economic interpretation of these changes is not strong.

Chart 3 shows the AFDC caseload from 1950 to 2000. On the chart, periods of economic recession are shaded, and periods of economic growth are shown in white. Historically, periods of economic growth have not resulted in lower welfare caseloads. The chart shows eight periods of economic expansion prior to the 1990s, yet none of these periods of growth led to a significant drop in AFDC caseload. Indeed, during two previous economic expansions (the late 1960s and the early 1970s), the welfare caseload grew substantially. Only during the expansion of the 1990s does the caseload drop appreciably.

How was the economic expansion of the 1990s different from the eight prior expansions? The answer is welfare reform.

Chart 3 does show that the national TANF decline has slowed appreciably during the current recession, which began in April 2001. Critics of reform might argue that this shows the state of the economy has been the dominant factor in the reduction of dependence. While it is true that the slowdown in the economy is affecting the decline in caseload, however, it is important to note the vast difference in trends before and after welfare reform. Prior to the mid-1990s, the AFDC caseload remained flat or rose during economic expansions and generally rose to a substantial degree during recessions. Since welfare reform, the welfare caseload has plummeted downward during good economic times and declined more slowly during the recession.

Thus, while the state of the economy does have an effect on AFDC/TANF caseloads, irrespective of economic conditions, the difference in caseload trends before and after reform is enormous. This difference is clearly due to the impact of welfare reform policies.

Another way to disentangle the effects of welfare policies and economic factors on declining caseloads is to examine the differences in state performance. The rate of caseload decline varies enormously among the 50 states. If improving economic conditions were the main factor driving down caseloads, the variation in state reduction rates should be linked to variation in state economic conditions. On the other hand, if welfare polices are the key factor behind falling dependence, the differences in reduction rates should be linked to specific state welfare policies.

In a 1999 Heritage Foundation study, "The Determinants of welfare Caseload Decline," one of the present authors examined the impact of economic factors and welfare policies on falling caseloads in the states.20 This analysis showed that differences in state welfare reform policies were highly successful in explaining the rapid rates of caseload decline. By contrast, the relative vigor of state economies, as measured by unemployment rates, changes in unemployment, or state job growth, had no statistically significant effect on caseload decline.

A recent paper by Dr. June O'Neill, former Director of the Congressional Budget Office, reaches similar conclusions. Dr. O'Neill examined changes in welfare caseload and employment from 1983 to 1999. Her analysis shows that in the period after the enactment of welfare reform, policy changes accounted for roughly three-quarters of the increase in employment and decrease in dependence. By contrast, economic conditions explained only about one-quarter of the changes in employment and dependence.21 Substantial employment increases, in turn, have led to large drops in child poverty.

Overall, the health of the economy in the mid and late 1990s did serve as a positive background factor contributing to positive changes in welfare dependence, employment, and poverty. It is very unlikely, for example, that dramatic drops in dependence and increases in employment would have occurred during a prolonged recession. However, it is also certain that good economic conditions alone would not have produced the striking changes that occurred in the late 1990s. It is only when welfare reform was coupled with a growing economy that these dramatic positive changes occurred.

WELFARE REFORM AND CHILD POVERTY

A recent paper by Dr. Rebecca M. Blank, former member of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Clinton White House, examines the link between welfare reform and child poverty.22 Professor Blank analyzes the income of families with children from 1992 to 2000 and finds that incomes rose for all but the bottom 2 percent of families with children. Moreover, poor families showed greater income gains than higher-income families, "suggesting that most poor families experienced larger income gains than did most middle and upper-middle income families."23

Dr. Blank's analysis shows a direct link between state welfare reform policies and rising incomes among poor families. States with welfare reform programs that offered "strong work incentives" showed greater increases in the income of single parents with children than did states with weak work incentives. Moreover,

at the bottom of the distribution, states with strong work incentives have the smallest share of children in families with negative changes in income, while states with the weakest work incentives show the highest share of children with [decreases in income].24

In other words, states with strong welfare work incentives had fewer families that lost income than did states with weak welfare work incentives. Blank finds that these income differences are the result of state welfare policies rather than differences in state economies.

In addition, Dr. Blank examines the effects of tough welfare reform "penalties" on the incomes of poor single-parent families. Examining the impact of stricter time limits and strong sanction policies that "provide a strong enforcement mechanism for women to participate in welfare-to-work programs," she finds that tough welfare policies had a positive effect in raising the incomes of poor families. Overall, states with stricter time limits and stronger sanction policies were more successful in raising the incomes of poor children than were states with lenient policies. Dr. Blank concludes that

states with strict or moderate penalties for not working consistently show higher income gains among poor children throughout the income distribution than do states with lenient penalties.... [I]t is the more lenient states with softer penalties where children's income seems to have grown least.25

Out-of-Wedlock Childbearing and the Economy

Out-of-wedlock childbearing and marriage rates have never been correlated to periods of economic growth. Efforts to link the positive changes in these areas to growth in the economy are without any basis in fact. The onset of welfare reform is the only plausible explanation for the shifts in these social trends. welfare reform affected out-of-wedlock childbearing and marriage in two ways.

First, even before passage of the law, the public debate about welfare reform sent a strong symbolic message that, in the future, welfare would be time-limited and that single mothers would be expected to work and be self-reliant. This message communicated to potential single mothers that the welfare system would be less supportive of out-of-wedlock childbearing and that raising a child outside of marriage would be more challenging in the future. The reduction in out-of-wedlock births was, at least in part, a response to this message.

Second, reform indirectly reduced welfare's disincentives to marriage. Traditional welfare stood as an economic alternative to marriage, and mothers on welfare faced very stiff financial penalties if they did marry. As women leave AFDC/TANF as a result of welfare reform, fewer are affected by welfare's financial penalties against marriage. In addition, some women may rely on husbands to provide income that is no longer available from welfare. Thus, as the number of women on welfare shrinks, marriage and cohabitation rates among low-income individuals can be expected to rise.

Welfare Reform and the Current Recession

When welfare reform was enacted, liberal opponents predicted that it would yield sharp increases in poverty even in good economic times; the effects of reform during a recession were expected to be disastrous. As noted, liberal predictions about the negative effects of reform during good economic times have been proven completely erroneous. Moreover, the disastrous effects expected of welfare reform during an economic downturn have, at least so far, failed to materialize during the current recession.

Historically, during a recession, overall child poverty rises by two to three percentage points. For example, during the economic downturn in the early 1990s, the overall child poverty rate rose from 14.8 percent to 17.8 percent. Historically, black child poverty rises even more sharply during a recession. During the back-to-back recessions in the early 1980s, for example, black child poverty rose by more than six percentage points, from 41.2 percent in 1979 to 47.6 percent in 1982.

However, during the current recession (which began in April 2001), these traditional negative patterns have not appeared. While the poverty rate for adults rose during 2001 in a manner consistent with prior recessions, the poverty rates for children in general -- and for black children in particular -- differed sharply from prior historical patterns. Despite the recession, from 2000 to 2001, the overall child poverty rate remained flat.26 The poverty rate for black children actually fell by a full percentage point from 31.2 percent in 2000 to 30.2 percent in 2001. Such a decline in black child poverty during a recession is without historical precedent.

While the child poverty figures for 2001 (the first year of the current recession) are unusually positive, a note of caution is warranted. The effects of a recession on poverty often continue and deepen for two or three years after the recession's onset. Thus, when the Census Bureau releases poverty figures for 2002 and 2003, it is quite possible that reported child poverty will increase.27 However, if the unusual poverty figures for 2001 are any indication, the overall increase in child poverty (if any) generated by the current recession is likely to be far milder than in prior economic downturns.

The welfare dependence figures during the current recession also differ sharply from prior recessions. As Chart 3 shows, the AFDC caseload almost always rose during recessions.28 In some cases, the increase in caseload was dramatic. For example, during the early 1990s, the AFDC caseload rose by around 30 percent. However, during the current recession, the TANF caseload has actually declined. Between the beginning of the recession in April 2001 and September 2002 (the date of the most recent available data), the caseload actually fell by 4.4 percent.

The fact that welfare caseloads have, up to now, declined during the current recession is good news. However, a note of caution is, again, warranted. The effects of a recession in increasing welfare dependence may continue for several years after the onset of the recession. Thus, it is possible that TANF caseloads will rise during 2003. However, the recent trends in caseload strongly suggest that, if TANF caseloads do rise in 2003, the increase will be quite small when compared to increases spurred by prior recessions.

The fact that child poverty has not, as yet, risen during the present recession is linked to the continuing decline of TANF caseloads. During previous recessions, large numbers of single mothers left employment and entered the AFDC program. Families on AFDC are almost always poor. Thus, increases in welfare caseloads during prior recessions invariably led to concurrent increases in child poverty. However, the work requirements and time limits established by welfare reform have created strong pressures discouraging single mothers from leaving employment and entering welfare. The fact that TANF caseloads have not risen during the current recession has, in turn, helped to limit any rise in child poverty.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The trends of the past six years have led some of the strongest critics of welfare reform to reconsider their opposition, at least in part. In 1996, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Human Services Policy Wendell Primus also resigned from the Clinton Administration to protest the President's signing of the welfare reform legislation, predicting that the new law would throw millions of children into poverty.

As Director of Income Security at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Primus has spent the past six years analyzing the effects of welfare reform. The evidence has tempered his earlier pessimism. "In many ways," he recently stated, "welfare reform is working better than I thought it would. The sky isn't falling anymore. Whatever we have been doing over the last five years, we ought to keep going."29

Wendell Primus is correct. When Congress reauthorizes the TANF program this year, it should push forward boldly to promote further the three explicit goals of the 1996 reform:

- To reduce dependence and increase employment;

- To reduce child poverty; and

- To reduce illegitimacy and strengthen marriage.

These three goals are linked synergistically. Work requirements in welfare will reduce dependence and increase employment, which in turn will reduce poverty. As fewer women depend on welfare in the future, marriage rates may well rise. Increasing marriage, in turn, is the most effective means of reducing poverty.

Next Steps in Reform

When Congress reauthorizes Temporary Assistance to Needy Families in 2003, it should take the following specific steps.

- Strengthen federal work requirements

Currently, about half of the 2 million mothers on TANF are idle on the rolls and are not engaged in constructive activities leading to self-sufficiency. This is unacceptable. Existing federal work requirements must be greatly strengthened so that all able-bodied parents are engaged continuously in supervised job search, community service work, or training.In addition, some states still provide federal welfare as an unconditional entitlement; recipients who refuse to perform required activities continue to receive most benefits. In reauthorizing the TANF program, Congress should ensure that the law prohibits federal funds from being misused in this manner in the future.

Some might object to toughening work requirements during a recession, but it is important to remember that the TANF reauthorization law will set the rules for the program not for one year, but for the next five years. Provisions to toughen federal work requirements can be phased in so that they do not take effect until 2005 or later, long after the current recession has passed.

- Strengthen marriage

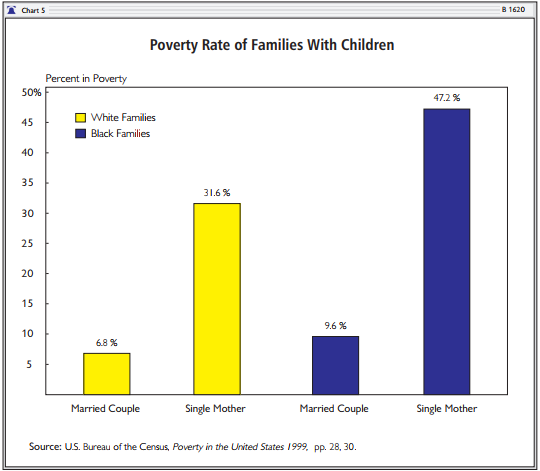

As Chart 5 shows, the poverty rate among single-parent families is about five times higher than the poverty rate among married-couple families. The most effective way to reduce child poverty and increase child well-being is to increase the number of stable, healthy marriages. This can be accomplished in three ways.

First, the substantial penalties against marriage in the overall welfare system should be reduced. As it is currently structured, welfare rewards illegitimacy and wages war against marriage. That war must cease.30

Second, the government should educate young men and women on the benefits of healthy marriage in life.

Third, programs should provide couples with the skills needed to reduce conflict and physical abuse and to increase satisfaction and longevity in a marital relationship.

The 1996 TANF law established the formal goals of reducing out-of-wedlock childbearing and increasing marriage, but despite nearly $100 billion in TANF spending over the past five years, the states have spent virtually nothing on specific pro-marriage programs. The slowdown in the growth of illegitimacy and the increases in marriage have occurred as the incidental byproduct of work-related reforms and not as the result of positive pro-marriage initiatives by the states. The current neglect of marriage is scandalous and deeply injurious to the well-being of children. In future years, at least $300 million in TANF funds should be earmarked for pro-marriage initiatives.

More than 20 years ago, President Jimmy Carter stated, "the welfare system is anti-work, anti-family, inequitable in its treatment of the poor and wasteful of the taxpayers' dollars."31 President Carter was correct in his assessment.

The 1996 welfare reform began necessary changes in the disastrous old welfare system. The rewards for non-work in the TANF program have been substantially reduced. But much more remains to be done. When Congress reauthorizes TANF this year, it should ensure that, in the future, all able-bodied welfare recipients are required to work or undertake other constructive activities as a condition of receiving aid.

But increasing work is not enough. Each year, one-third of all children are born outside of wedlock; this means that one child is born to an unmarried mother every 25 seconds. This collapse of marriage is the principal cause of child poverty and welfare dependence. In addition, children in these families are more likely to become involved in crime, to have emotional and behavioral problems, to be physically abused, to fail in school, to abuse drugs, and to end up on welfare as adults.

Despite these harsh facts, the anti-marriage effects of welfare, which President Carter noted over two decades ago, are largely intact. The current indifference and hostility to marriage in the welfare system is a national disgrace. In reauthorizing TANF, Congress must make the rebuilding of marriage its top priority. The restoration of marriage in American society is truly the next frontier of welfare reform.

Robert Rector is Senior Research Fellow in Domestic Policy Studies, and Patrick F. Fagan is William H. G. FitzGerald Research Fellow in Family and Cultural Issues, at The Heritage Foundation. This paper is an updated version of Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1468, published on September 5, 2001.