I am Rachel Greszler, Senior Policy Analyst in Economics and Entitlements in the Center for Data Analysis at the Heritage Foundation. The views I express in this testimony are my own and should not be construed as representing any official position of The Heritage Foundation.

Vice-Chair Klobuchar, Chairman Brady, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today on the topic of workplace empowerment.

My testimony consists of three components: First, the lack of empowerment that exists for workers without jobs in today’s weak labor market; second, policies that are holding back workplace empowerment; and third, some examples of companies that are leading the way in workplace empowerment.

Workplace Empowerment Is Nonexistent for the Unemployed

Empowerment encompasses a number of qualities including confidence, autonomy, and access to authority and influence. In short, empowerment is the opposite of micromanagement. Empowerment is beneficial for employees and employers alike: It leads to more satisfied and motivated employees and higher levels of productivity and innovation. This, in turn, helps economic growth and government tax revenues.

Employees’ sense of workplace empowerment varies significantly across the labor force, but there is a universal lack of empowerment among the unemployed. Before workers can become empowered, they must first have a job. Government assistance can prevent the unemployed from living in poverty, but it cannot embolden them in the same way as a productive and meaningful job.

With nearly 10 million workers unemployed and another 8 million having left the labor force since the start of the recession, lack of employment is a significant barrier to workplace empowerment.

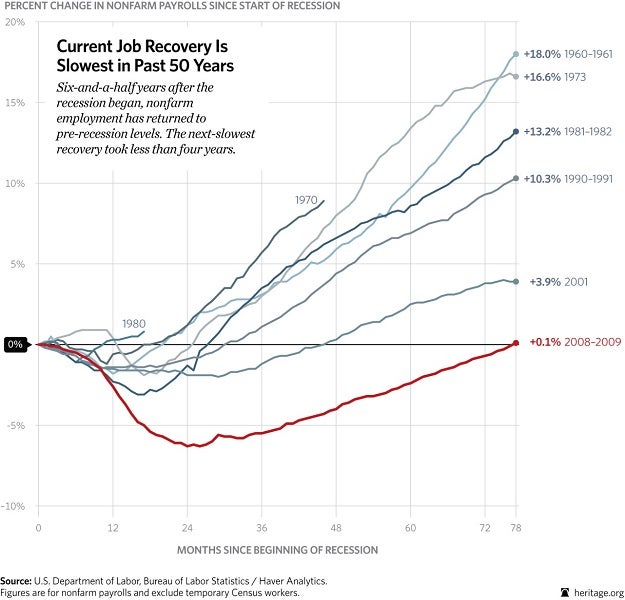

A picture is often worth a thousand words, and the graph I have included below that compares the current labor market recovery to that of other post-WWII recoveries is very telling. Employment during recessions and recoveries typically follows a U-shaped or V-shaped pattern. Declines in employment are typically matched with equal rebounds in employment. On average, it has taken 25 months for employment to return to its pre-recession level. In the current recovery, however, it took three times that amount, or 76 months. Last month, May 2014, was the first month in which total nonfarm payroll employment finally caught back up to its pre-recession level.

While the official unemployment rate has declined, millions of workers have left the labor force. The labor force participation rate today is at a 36-year low of 62.8 percent. While some of the decline in labor force participation can be attributed to demographics—the aging of the baby boomers and changes in college attendance—a study by my colleague James Sherk at The Heritage Foundation shows that only one-quarter of the decline in labor force participation is the result of demographic changes[1] Netting out those demographic effects, the labor force today is nearly 6 million workers below what it would be if labor force participation were at its pre-recession level.[2]

Lower labor force participation translates into lower output, smaller incomes, higher government spending, and lower tax revenues. These are all drains on the economy.

Why Is Employment Lacking?

According to the April 2014 survey by the National Federation of Independent Business, half of small and independent businesses say that it is a bad time to expand facilities while only eight percent say it is a good time[3] When asked to cite their single biggest problem, taxes were the most frequently cited concern, followed by government requirements and red tape.[4]

Obamacare is one policy that has contributed to higher taxes and regulations. According to recent Federal Reserve Beige Books, “[C]ontacts remain concerned about general macroeconomic conditions and uncertainty surrounding healthcare reform,” and “many contacts indicated that non-wage labor costs increased because of higher healthcare premiums.”[5]

Other unnecessary regulations are significantly driving up employers’ costs and reducing employment. For example, Section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act requires publicly traded firms to have an annual external audit of their financial controls. This regulation provides little benefit to shareholders, but it costs an average 0.5 percent of revenues ($1.5 million a year) for small to medium-sized companies. Nationally, Section 404 costs the economy $35 billion a year.[6]

Increased costs and regulations make it harder for businesses to start up and expand. A recent study by the Brookings Institute noted a sharp decline in business dynamism and entrepreneurship over the past decades. According to the report,

Business dynamism and entrepreneurship are experiencing a troubling secular decline in the United States.… [B]usinesses are hanging on to cash, fewer people are launching firms, and workers are less likely to switch jobs or move.[7]

The authors of the report noted that mounting government regulations could be contributing to the decline in dynamism and entrepreneurship as it has become extremely costly for younger and smaller firms to comply with ever-growing regulations.

Not only is it difficult for businesses to expand and hire more workers, but it has become easier for workers to not work. The availability of generous government transfer programs and a permissive disability insurance program make it possible for able-bodied individuals to maintain a comfortable standard of living without working.

Less work means lower economic output. This creates a double whammy for the federal budget; lower output leads to fewer tax revenues, and transfer payments to low-income, unemployed, and disabled workers drive up government spending.

Policymakers need to relieve employers and entrepreneurs of the red tape and economic burdens that are holding them back from investing, expanding, and hiring more workers. On the employee side, policymakers need to create an environment that encourages and rewards work while making it more difficult for able-bodied individuals to choose not to work. Reform of the disability insurance program—to reduce abuse of the program and preserve benefits for the truly disabled—should be the first step.

Empowering Workers Who Have Jobs

For the roughly 146 million workers who are fortunate to be employed today, a number of actions could help empower these workers with more control over their jobs, more input into their companies’ policies and plans, greater opportunities for advancement, and ultimately higher levels of satisfaction and productivity.

Labor Laws. For starters, U.S. labor laws are outdated. Laws governing labor unions were created in the 1930s for a largely industrial economy that no longer exists. Whereas unions were initially thought to empower workers through collective bargaining, their impact today is more often to impede workers by preventing individual raises and excluding workers from having a formal voice on the job. Furthermore, labor laws were created at a time when few women participated in the labor force, so it is no wonder these laws take little account of the needs of working women.

Unions Restrict Employment. Economically, unions function as labor cartels; they restrict the supply of labor in order to drive up its cost. This also reduces the quantity of labor employers demand. Unions benefit their members by restricting competition and reducing job growth in their industry. The recent union attempts to prevent non-union competitors like Uber and Norwegian Air from entering the taxi and international airline markets, respectively, illustrate this phenomenon.

This also explains why unionized businesses create significantly fewer jobs than non-unionized ones. While manufacturing has been declining for decades in America, the entire decline has occurred among unionized manufacturers. Non-union manufacturing employment in 2013—at 12.6 million—stands at the same level it did in 1977. Unionized manufacturing, however, declined 80 percent over that same period, from 7.5 million to 1.6 million[8]

Union Salary Negotiations Create Winners and Losers. Not only do unions lead to lower employment, but their salary negotiations effectively create winners and losers. By forcing employers to base salaries on seniority, more productive employees cannot be recognized for their contributions while less productive employees receive unmerited pay.

The case of Giant Eagle is a perfect example. In 2011, the Giant Eagle grocery store in Edinboro, Pennsylvania, rewarded two dozen of its hardest working employees with a pay raise above their union rates. However, some of those employees receiving raises lacked seniority in comparison to those who did not receive raises, so the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 23 union filed a grievance.[9] An arbitrator, and later the courts, sided with the union and awarded it exactly what it wanted; Giant Eagle was forced to rescind the pay increases.

Performance pay can raise the incomes of all workers. When employees are paid based on their performance, they tend to be more productive. Additionally, performance pay is associated with higher overall job satisfaction. [10]

Unionized pay scales can be particularly harmful to women because women are more likely to take time out of the labor force to care for children. Time out of the labor force translates to lower seniority, and therefore lower pay.

Policymakers should remove the ability of unions to veto individual raises. Senator Marco Rubio (R–FL) and Representative Todd Rokita (R–IN) have introduced the Rewarding Achievement and Incentivizing Successful Employees (RAISE) Act, which would retain union wages as a wage floor while allowing employers to raise wages above that floor[11] A Heritage Foundation report finds that the RAISE act could increase the average union member’s salary by $2,700 to $4,500 per year.[12]

Unions Restrict Employee-Employer Communication. Federal law prohibits any formal two-way communication between employees and employers over working conditions outside collective bargaining. The union speaks on the workers’ behalves; workers cannot speak on their own and if they do not have a union, they lack an institutional voice entirely—even if both workers and management want such dialogue.

Federal law denies workers who do not want union representation a formal voice on the job, as the recent vote at Volkswagen demonstrated. The company wanted to create a Works Council to expand its employees’ voice in corporate governance. Volkswagen believed this would improve its operations. Volkswagen’s employees, however, did not want the United Auto Workers (UAW) to represent them and voted against unionizing. As one Volkswagen employee told reporters, “We also looked at the track record of the UAW. Why buy a ticket on the Titanic?”[13] Consequently, Volkswagen could not implement a Works Council. Its employees’ aversion to the UAW also prevented them from speaking through formal non-union channels.

It is hard for workers to feel empowered or to have control over their job if they can only approach their employer with a union representative present and if their concerns can only be addressed through a collective bargaining process.

Women are also more likely to be hurt by this lack of direct communication between employees and employers over working conditions. Women are more likely to have individual needs and circumstances that could be easily accommodated through mutual negotiations with an employer. For example, a woman returning from maternity leave may want to work part-time for a short period, or a woman caring for an elderly parent may suddenly need to adjust her schedule or take time off. Universal policies, as negotiated by unions, are unlikely to meet the needs of women who often require greater flexibility in the workplace than men.

Employee-involvement (EI) programs could help give workers a voice on the job. EI programs consist of groups of employees and supervisors—often in the form of committees or teams—that meet to discuss and confront workplace issues. Polls show that 60 percent of workers prefer IE programs over labor unions or government regulations to improve working conditions.[14]

Yet, under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), most EI programs are illegal unless they are run by an outside union.[15]

Congress should remove the section 8(a)(2) proscription on employee involvement programs to allow employees direct access to employers regarding workplace conditions.

Ease Licensure Laws. Licensure laws are requirements, most often by states, to obtain a license to practice a certain trade. Requirements—in terms of training, exams, and other qualifications—vary significantly across professions and across states. Some professions, such as emergency medical technicians and cosmetologists require a license in every state while others, such as fortune tellers and cat groomers, are less likely to require licensure.

Despite the assumption that licensing is necessary for certain professions, evidence suggests that licensing does not improve quality. A study of dental hygienists showed that performance in states that required them to operate under the supervision of a dentist was not superior to performance in states that allowed them to operate separately and refer patients to dentists, but that stricter licensing laws reduced the supply of hygienists and increased the prices of dental care.[16] Additionally, because dentists are predominantly male and dental hygienists are predominantly female, laws that require hygienists to practice under the supervision of dentists tend to benefit males at the expense of females.[17]

Additionally, lack of uniformity in licensing requirements across states suggests that many licensure requirements are unnecessary and onerous. A study by the Institute for Justice looked at 102 licensed occupations with below-average wages. It found that only 15 of the occupations required licensing in 40 states or more, and of 102 total licensed occupations, the average state required licensing for only 22.[18] As the study pointed out, requirements for the same license vary significantly across states: For example, 10 states require manicurists to obtain four or more months of training while others require fewer than 10 days.[19]

Many licensing requirements are arbitrary and irrational. For example, the average cosmetologist spends 372 days in education and training whereas the average EMT spends only 33 days.[20] Excessive requirements for certain occupations restrict the supply of labor for those occupations, driving up wages and prices in those occupations.

Adam Smith described licensure laws as a conspiracy of trades to reduce the availability of skilled craftsmen in order to raise wages.[21] According to a report by the Kauffman Task Force on Entrepreneurial Growth,

Licensing regulation enables incumbent providers to thwart competition and innovation by raising entry barriers to entrepreneurs who may be able to deliver these services at lower cost and/or higher quality[22]

Excessive licensing can reduce employment and incomes and prevent individuals from improving their economic circumstances. A high percentage of licensed occupations are ones that low-income workers and women would find highly desirable and achievable if it were not for the time and costs required to obtain a license. Low-income individuals often lack the resources necessary to obtain a desired license, so they end up staying put in low-paying jobs with little opportunity for advancement. Likewise, it is generally much harder for mothers who want to make some extra money cutting hair to spend the time and money necessary to obtain a barber’s license than it is for a man or childless woman.

States should be encouraged to re-evaluate their licensure laws. Licensing requirements should be eliminated or reduced in accordance with cost-benefit analysis of their public interest and economic consequences. Additionally, states should allow cross-state licensing reciprocity so that a massage therapist who practices in one state would not have to go through the entire licensure process again upon moving to a different state.

Encourage Cash Option in Cafeteria Plan Choices. A lesser known or publicized way to empower workers is by allowing employees to exchange cash wages for cafeteria plan benefit options. Cafeteria plans are compensation options offered by employers to employees in exchange for what is typically a pre-tax reduction in salary. Common cafeteria plan offerings include flexible spending accounts, transportation benefits, and health insurance premiums.

In the case of health insurance premiums, employers often pay thousands of dollars (even upwards of ten thousand) of workers’ premiums. However, if an employee does not elect to sign up for health insurance coverage, they do not receive any additional compensation in return for the savings to their employer.

Women, primarily because of their greater propensity to take time out of the labor force or work part-time, are more likely to turn down employer-provided health insurance because they already have family coverage through their husband. If employers were to give employees the option of cash wages in exchange for not electing employer-provided benefits, many women would be able to garner significantly higher wages. The option of higher wages would also encourage labor force participation.

As an added bonus, allowing employees to choose between cash wages and health insurance benefits could drive down health care costs. Greater awareness of the total cost of health insurance premiums could spur employees to demand less costly, more efficient plans, such as high-deductible and health spending account plans.

Avoid Government Micromanagement of Businesses

Employee empowerment is an important component of workplace empowerment, but if employers are not empowered to run their businesses based on their own needs, workers cannot be empowered. A number of recent proposals and executive actions seek to micromanage employers. Government micromanagement of firms’ employment practices is worse than firm-level micromanagement.

The proposed Paycheck Fairness Act would effectively end performance-based pay. By significantly increasing businesses’ liabilities for pay differentials caused by factors other than sex, the law would effectively force employers to implement one-size-fits-all pay scales that would translate to one-size-fits-all jobs. Few businesses can claim that performance bonuses or flexible workplaces are a matter of “workplace necessity.” Consequently, flexible work arrangements and employee autonomy would fall by the wayside. Despite its name, the Paycheck Fairness Act would be anything but fair to women who have worked long and hard to achieve increased flexibilities and opportunities in the workplace today.

Another proposed policy that would limit employers’ ability to pay employees according to their contributions is the President’s proposal to raise the cap for overtime pay. Currently, salaried employees who earn less than about $24,000 per year must receive overtime pay if they work more than 40 hours per week. Salaried employees who earn more than that are only required to receive overtime if they do not pass the test of having sufficiently advanced job duties, as defined by Department of Labor regulations. The White House has suggested that this cap should be raised to somewhere between $28,600 and $50,440.[23]

These regulations will not accomplish the President’s goal of raising wages. Even Jared Bernstein, the former top economic advisor to Vice President Biden, has written that employers will offset higher overtime costs by reducing base pay rates, resulting in little change to total overall pay.[24] A recent lawsuit illustrates this phenomenon. In a settlement IBM agreed to provide several thousand salaried workers overtime. IBM also cut those employees’ base salaries by 15 percent so that after overtime they received the same as before.[25]

Unfortunately, expanding overtime to every salaried employee making less than $50,000 a year will force their employers to rigorously monitor employee hours to track overtime liability. This would effectively prohibit the flexible work arrangements that many employees—and especially working mothers—value. As a working mother, I negotiated to work from home one or more days per week. I know of many other working mothers who also enjoy the ability of working from home; not only does it save time and money commuting, but the lack of office distractions creates a highly productive environment.

But firms cannot track the hours of employees who work from home. As a result, companies would be less likely to allow employees to telework if they are required to pay them overtime. This was precisely the case with Pitney Bowes, a large manufacturer. This company wanted to allow certain employees to work from home, but that they could not because the employees qualified for overtime and the firm could not track their hours outside the office[26]

Instead of issuing top-down regulations on businesses’ employment practices, the government should instead encourage employers to empower employees with individual choices, flexibility, input, and opportunity. Employers can only provide these things when they are allowed to pay employees based on their individual performance.

Examples of Entrepreneurs and Workplace Empowerment: Etsy, Uber, and Food Trucks

Etsy is an online marketplace where people sell and buy unique, often handmade goods. It was founded in 2005 and did not become profitable until four years later, in 2009. Today, it has 500 employees, more than 1 million active shops/sellers, more than 40 million members, and $1.35 billion in 2013 sales revenues.[27]

Setting up a marketplace to sell one’s goods—either online or in an actual building—typically requires a great deal of time, money, paperwork, and commitment. Etsy provides a marketplace for individuals to sell their goods and services with minimal cost, administration, and bureaucracy. It is a place where individuals can test the waters, work as much or as little as they like, earn pocket money or significant incomes, and act as their own bosses. Etsy is a place where individuals do not have to jump through a bunch of hoops, invest a significant amount of money, or commit to a regular work schedule.

The availability of work options such as Etsy allows individuals who many not otherwise participate in the labor force to do so. Of Etsy’s more than 1 million sellers: 88 percent are women; 74 percent consider their Etsy shops as businesses; and 94 percent desire to increase their future sales. This suggests that nearly all Etsy sellers are willing to work more. I suspect that a significantly smaller portion of all workers in the U.S. would say they want to spend more time in their jobs. When workers have input into their jobs and control over their schedules, they are far more likely to feel empowered and to work more.

Two other examples of entrepreneurship and workplace empowerment exist just outside the steps of Congress: Uber and food trucks. Uber is a software company that contracts with individual drivers who use Uber’s technology in exchange for a cut of the fares they receive. Uber’s unique technology allows individuals searching for transportation services to “request, ride, and pay via [their] mobile phone.” Customers can choose their driver based on proximity, view their driver’s impending arrival, and enjoy cash-less transactions (tips are included in the base fair) through a mobile device app. Uber drivers act as their own bosses, working as much or as little as they like. While individual drivers are not employees of Uber, Uber nonetheless prides itself on employee empowerment. According to its website:

“Every role matters because anything and everything our employees work on affects the daily lives of people around the world.”

“At Uber, the best idea always wins. We empower our teams to find creative solutions to difficult problems.&rdquo[28]

Food trucks are another example of entrepreneurship and empowerment flourishing under fewer government constraints. Because food trucks operate without a brick-and-mortar storefront, they enjoy lower start-up and operational costs, and require arguably fewer regulations.

Both Uber and the food truck industry offer superior customer service, as evidenced by their success, yet these innovative business structures are being threatened by demands—from their competitors—to impose hefty new regulations and costs that will depress their growth and profitability.

Congress, along with state and local policymakers, should refrain from imposing unnecessary and costly regulations on new, innovative companies and should instead look to the success of these businesses as ways to promote greater entrepreneurship and empowerment. When the entrance of new businesses or markets reveals a comparative advantage, policymakers should seek to lift the disadvantaged up to the level of the advantaged by reducing their costs and regulations, as opposed to driving down those with a current advantage through new costs and regulations.

Conclusion

In summary, the first step toward workplace empowerment is for individuals to have a workplace in which they can become empowered. Policymakers should consider cost-benefit analysis of existing regulations and red tape, create greater certainty for businesses through fiscal discipline, and reform programs that discourage work among able-bodied individuals. Second, labor laws should be brought up to date, giving employees an individual voice on the job and the opportunity to be paid according to their work. Third, high marginal tax rates should be reduced and programs that impose disincentives for work should be reformed. Fourth, states should ease restrictions and requirements on licensure laws where evidence shows such laws to be unnecessary and harmful. Fifth, employers should consider allowing employees to choose between employer-provided benefits such as health insurance and cash or other benefits. Sixth, policymakers should look to the successes of less regulated businesses and entrepreneurs as ways to empower existing employers and employees, and should avoid micromanaging employers in ways that will reduce employee empowerment.

The Heritage Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization recognized as exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. It is privately supported and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work.

The Heritage Foundation is the most broadly supported think tank in the United States. During 2013, it had nearly 600,000 individual, foundation, and corporate supporters representing every state in the U.S. Its 2013 income came from the following sources:

Individuals 80%

Foundations 17%

Corporations 3%

The top five corporate givers provided The Heritage Foundation with 2% of its 2013 income. The Heritage Foundation’s books are audited annually by the national accounting firm of McGladrey, LLP.

Members of The Heritage Foundation staff testify as individuals discussing their own independent research. The views expressed are their own and do not reflect an institutional position for The Heritage Foundation or its board of trustees.

Endnotes

[1]James Sherk, “Not Looking for Work: Why Labor Force Participation Has Fallen During the Recession,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 2722, update, September 5, 2013, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2013/09/not-looking-for-work-why-labor-force-participation-has-fallen-during-the-recession.

[2]Author’s calculations. The labor force participation rate was 66.0 percent in December 2012 and 62.8 percent in May 2014. If the May participation rate were 66.0 percent, rather than 62.8 percent, the size of the labor force would be greater by 7.9 million. Netting out a 25 percent demographic factor, the labor force would be higher by 6 million.

[3]William C. Dunkelberg and Holly Wade, “NFIB Small Business Economic Trends,” National Federation of Independent Business, May 2014, http://www.nfib.com/Portals/0/PDF/sbet/sbet201405.pdf (accessed June 13, 2014).

[4]Ibid.

[5]Federal Reserve Board, “Summary of Commentary on Current Economic Conditions by Federal Reserve District,” March 5, 2014, http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/beigebook/files/Beigebook_20140305.pdf (accessed June 16, 2014).

[6]James Sherk, “Avoiding a Lost Generation: How to Minimize the Impact of the Great Recession on Young Workers,” testimony before the Joint Economic Committee, U.S. Congress, May 26, 2010, http://www.heritage.org/research/testimony/avoiding-a-lost-generation-how-to-minimize-the-impact-of-the-great-recession-on-young-workers#_ftn14.

[7]Ian Hathaway and Robert E. Litan, “Declining Business Dynamism in the United States: A Look at States and Metros,” The Brookings Institute, May 2014, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2014/05/declining%20business%20dynamism%20litan/final2_declining_business_dynamism_its_for_real_hathaway_litan.pdf (accessed June 13, 2014).

[8]Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson, Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey, Union Stats, http://www.unionstats.com (accessed June 13, 2014).

[9]James Sherk, “Want to Help Workers? Reinvent the Union,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, May 2, 2014, http://www.heritage.org/research/commentary/2014/5/want-to-help-workers-reinvent-the-union.

[10]Colin Green and John S. Heywood, “Does Performance Pay Increase Job Satisfaction?” Lancaster University, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and University of Birmingham, March 29, 2007, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00649.x/pdf (accessed June 17, 2014).

[11]Rewarding Achievement and Incentivizing Successful Employees (RAISE) Act, S. 1542, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/s1542 (accessed June 17, 2014), and Rewarding Achievement and Incentivizing Successful Employees (RAISE) Act, H.R. 3154, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr3154 (accessed June 17, 2014).

[12]James Sherk and Ryan O’Donnell, “RAISE Act Lifts Pay Cap on Millions of Workers,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 2702, June 19, 2012, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2012/06/raise-act-lifts-pay-cap-on-millions-of-american-workers.

[13]Bernie Woodall, “Loss at Volkswagen Plant Upends Union’s Plans for U.S. South,” Reuters, February 15, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/02/15/us-autos-vw-election-idUSBREA1D1DP20140215 (accessed June 16, 2014).

[14]James Sherk, “Expand Employee Participation in the Workplace,“ Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4169, March 13, 2014, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2014/03/expand-employee-participation-in-the-workplace.

[15]Ibid.

[16]Morris M. Kleiner and Robert T. Kudrle, “Does Regulation Affect Economic Outcomes? The Case of Dentistry,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 43 (October 2000), pp. 547–582, http://pirate.shu.edu/~rotthoku/Liberty/Does%20Regulation%20Affect%20Economic%20Outcomes%20the%20Case%20of%20Dentistry.pdf (accessed June 17, 2014).

[17]Morris M. Kleiner and Kyoung Won Park, “Battles Among Licensed Occupations: Analyzing Government Regulations on Labor Market Outcomes for Dentists and Hygienists,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 16560, November 2010, http://www.nber.org/papers/w16560 (accessed June 16, 2014).

[18]Dick M Carpenter II, Lisa Knepper, Angela C. Erickson, and John K. Ross, “License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing,” Institute for Justice, May 2012, https://www.ij.org/images/pdf_folder/economic_liberty/occupational_licensing/licensetowork.pdf (accessed June 13, 2014).

[19]Ibid.

[20]Ibid.

[21]Morris M. Kleiner and Alan B. Krueger, “Analyzing the Extent and Influence of Occupational Licensing on the Labor Market,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 14979, May 2009, http://www.nber.org/papers/w14979.pdf (accessed June 13, 2014).

[22]The Kauffman Foundation, “A License to Grow: Ending State, Local, and Some Federal Barriers to Innovation and Growth in Key Sectors of the Economy,” Kauffman Task Force on Entrepreneurial Growth, January 2012, http://www.kauffman.org/~/media/kauffman_org/research%20reports%20and%20covers/2012/02/a_license_to_grow.pdf (accessed June 13, 2014).

[23]Zachary A. Goldfarb and Josh Hicks, “Obama’s Expected Change to Overtime Rules Would Make More Eligible for Extra Pay,” The Washington Post, March 12, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/obama-to-order-expansion-of-overtime-pay/2014/03/12/3262d334-a9f2-11e3-8599-ce7295b6851c_story.html (accessed June 13, 2014).

[24]Ross Eisenbrey and Jared Bernstein, “New Inflation-Adjusted Salary Test Would Bring Needed Clarity to FLSA Overtime Rules,” Economic Policy Institute, March 13, 2014, http://www.epi.org/publication/inflation-adjusted-salary-test-bring-needed/ (accessed June 16, 2014).

[25]James Sherk, “Goodbye, Flexible Work Arrangements,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, March 20, 2014, http://www.heritage.org/research/commentary/2014/3/goodbye-flexible-work-arrangements (accessed June 13, 2014).

[26]Ibid.

[27]Etsy, “At a Glance,” https://www.etsy.com/press?ref=ft_press (accessed June 13, 2014).

[28]Uber: Employment, https://www.uber.com/jobs (accessed June 13, 2014).