The U.S. economy has been doing well since Donald Trump settled into the Oval Office. Most recently, he celebrated second quarter GDP growth of 4.1%.

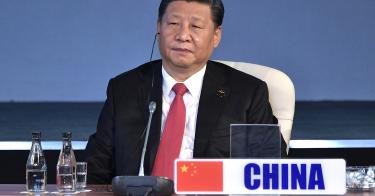

Meanwhile, things are not going so well for President Xi Jinping's China. Cracks are widening for China's economy. Its second quarter GDP growth, officially reported as 6.7%, is slowing markedly.

For those leery of a full-fledged trade war, a strengthening U.S. economy and a weakening Chinese economy represents a worst-case scenario, one that could lead to a protracted trade war instead of fruitful negotiations.

Part of the danger lies in the possibility that economic nationalists in the Trump administration will look at these numbers and wrongly proclaim that the tariffs slapped on select Chinese imports last quarter are, indeed, weakening China's economy. This perception may lead them to recommend that the U.S. double down on its pressure-through-tariffs approach to force China to make reforms.

It is true that tariffs are starting to hurt. But they're hurting both U.S. and Chinese industries caught in the cross fire between Washington and Beijing.

The administration recognizes this. And from the swamp emerges the Washington solution of throwing money at its problems — distributing $12 billion in relief to farmers.

Meanwhile, Beijing is also turning to a Big Government "solution" for its problems. It's looking to ease trade woes and boost domestic growth via monetary policy — injecting $74 billion into the economy to improve liquidity.

On both sides of the Pacific, then, leaders are asking their constituents to buckle down for the greater good.

Amid all the hubbub over trade policy, what's easily overlooked is the fact that America's current economic success — and China's growing problems — arise not from trade but from macroeconomic factors. In both countries, the economies are driven primarily by domestic consumption.

Private consumption accounts for roughly 69% of U.S. GDP and 40% of China's GDP. Total trade makes up only about 26% of U.S. GDP and 37% of China's, respectively. Meanwhile, bilateral trade accounts for only 15 percent of each country's total trade.

To ascribe China's second-quarter stall to U.S. tariffs on select products such as solar panels, steel, and aluminum, is to credit the tariffs with far too much influence. China's economy is much, much bigger than that.

One could argue that the same holds true regarding the effect of the tariffs stateside. Even the potential loss of 500,000 American jobs from tariffs on steel, aluminum, and Chinese imports, though devastating to the workers affected, is a statistical drop in the bucket of U.S. employment — now running at an impressive 156 million.

But the number of jobs at risk could increase dramatically if the administration goes ahead with plans to tax an additional $200 billion worth of Chinese imports or, as the president recently remarked, slap tariffs on every single product imported from China. And dramatically upping the stakes in this fashion is more likely to happen if supporters of tariffs believe they're working.

Behind-The-Scenes Dealing

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is reportedly in "quiet conversations" with Beijing to avert this emerging trade war. Perhaps these behind-closed-door discussions will result in a deal before the end of August, after which new U.S. tariffs could be levied.

A more formal approach might be worthwhile. Taking another crack at the U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue that began and ended last July, or reconvening the Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade would signal willingness to work through the problems together.

On the bright side, China's slowing economic growth could present an opportunity for market reform. Slowing growth was a leading factor in Beijing's decision to join the World Trade Organization and make market reforms in the late 1990s. The U.S. should stand ready now to help China move further along this path.

But a weakening Chinese economy doesn't mean U.S. tariffs are working. And current U.S. policies toward China seem more like American industrial policy than an attempt to reform China.

For now, the combination of a slowing Chinese economy and a growing U.S. economy threatens to lead us into a real trade war.

This piece originally appeared in Investors Business Daily