The Not-So-Great-Society

Lindsey M. Burke, Ph.D., and Jonathan Butcher (Editors)

Facts & Figures

- Head Start has had little to no impact on parenting practices, or the cognitive, social-emotional, and health outcomes of participants.

- Head Start had harmful effects on behavior and peer relations.

- Head Start has cost $240 billion since its inception in 1965.

- Spending per-pupil on K-12 education has quadrupled in real terms since 1960.

- Scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) have changed little since the early 1970s.

- The current gap in learning between students from the highest 10 percent and lowest 10 percent of the income distribution is roughly four years of learning – the same as it was when Johnson launched his War on Poverty.

- The federal government now originates and services nearly 90 percent of all student loans.

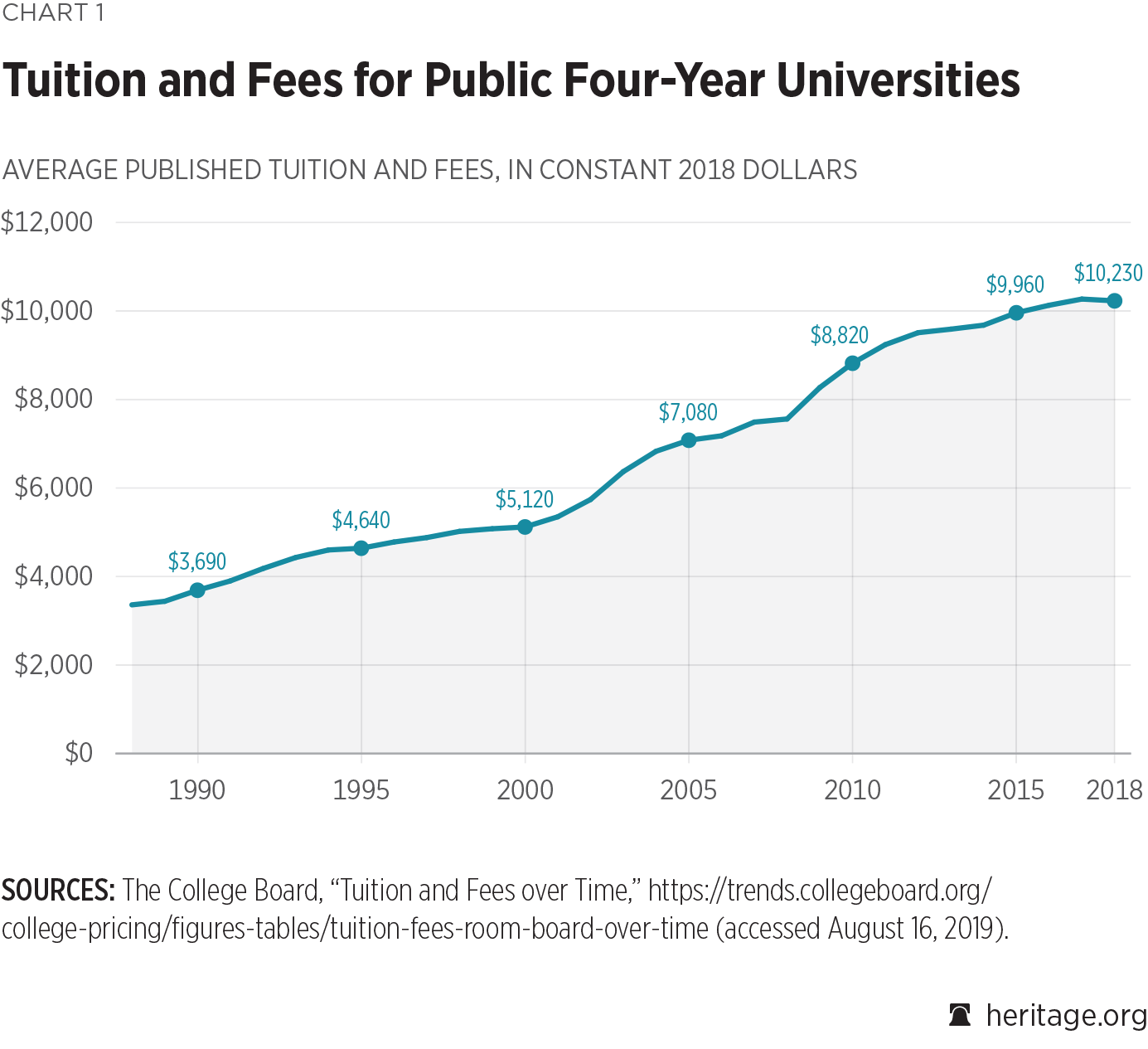

- College tuition at public universities has increased 213% since 1987.

- Americans hold more than $1.6 trillion in outstanding student loan debt.

- 44 percent of college graduates are in jobs that do not require a college degree.

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Note from the Editors

Part I: Half a Century Later, a Clear Failure

- Chapter 1

- The Push for a “Great Society”: Promises and Programs

- Chapter 2

- The Productivity Decline in American Public Schools Since the 1965 ESEA: Trends in Spending, Staffing, and Achievement

- Chapter 3

- The Opportunity Costs of Federal Administrative Compliance Burdens for States and Schools

- Chapter 4

- The Fall of Educational Productivity and Policy Paralysis

Part II: The War on Poverty Hires a Nanny: Federal Early Childhood Education and Care

- Chapter 5

- Head Start: Promise and Failures

- Chapter 6

- Effectiveness of Preschool: The Research Literature

- Chapter 7

- Support Children, Not Child Care

Part III: The War on Poverty in the Classroom: Federal Involvement in Elementary and Secondary Education

- Chapter 8

- Student Achievement Gap Fails to Close for Nearly 50 Years—It Is Time to Focus on Teacher Quality

- Chapter 9

- Explaining the Stagnation of America’s Students: The Education Monopoly and Misaligned Incentives

- Chapter 10

- Classroom Content: A Conservative Conundrum

Part IV: The War on Poverty Goes to College: Laying the Groundwork for Federalized Higher Education

- Chapter 11

- The Johnson Era: Federal Involvement in Higher Education

- Chapter 12

- Do America’s Universities Undermine the Public Good?

- Chapter 13

- ls College Worth It? How the War on Poverty Relates to the “Sheepskin Effect” and Upward Mobility in America

- Chapter 14

- Middle America Pays the Price for War on Poverty Policies—Including in College

Part V: A Comprehensive Conservative Vision for Educational Excellence

- Introduction to Part V

- From the “Great” Society to Civil Society

- Chapter 15

- What Is the Purpose of Education?

- Chapter 16

- Better Options for Better Preschool: Creating the Conditions for Family Care and Private Providers

- Chapter 17

- What Does the Evidence Say About Education Choice? A Comprehensive Review of the Literature

- Chapter 18

- Helping Students Succeed in School and Life with Education Savings Accounts

- Chapter 19

- The Classical Charter Movement: Recovering the Social Capital of K–12 Schools

- Chapter 20

- The Homeschooling Advantage: Examining the Research, Exploring the Future of the Movement

- Chapter 21

- A Better Path Forward: Re-Thinking Government Student Loans and Grants

- Chapter 22

- Conserve Free Speech on Campus

- Chapter 23

- The Comprehensive Conservative Agenda for Restoring Excellence in Education

- Conclusion

- Restoring Education Excellence in America

- Contributors

Foreword

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced his “Great Society” proposal, which would create new welfare programs, expand food stamps, give birth to Medicaid and Medicare, fund the arts, and more. It would also continue the departure from nearly 200 years of American tradition and increase the federal government’s involvement in local education significantly. President Johnson and those who supported his programs believed that greater government involvement in education, especially preschool through high school, could break the cycle of poverty for poor families.

When the President told the American people that they must accept “greater government activity in the affairs of the people,” little did they know how destructive a bargain they were making. In 1965, the Great Society’s “War on Poverty” began a massive infusion of federal tax dollars and involvement into pre-K and K–12 education. It also created new taxpayer-underwritten student loans and grants for the general public to attend college. Since then, federal taxpayers have spent $2 trillion on K–12 education alone—to say nothing of the billions spent annually on student loans and grants.

Introduction

Note from the Editors

This book comes at an important moment in time. Federal education programs and spending formulas that were written when Get Smart, Gunsmoke, and Green Acres led the TV ratings are not working for families today watching reruns of these shows on demand. Americans, rightfully, expect customization and responsiveness on the part of service providers, from hailing a ride with a smartphone to choosing how and where their children are educated.

As the year 2020 approaches, Americans still associate schooling with housing—because the federal government still assigns children to schools based on their families’ ZIP code. This arrangement has not only produced significant inequities in education, but has left low-income children several grade levels behind their peers in math and reading.

Chapter 1

The Push for a “Great Society”: Promises and Programs

In May 1964, more than 90,000 students and guests gathered on the University of Michigan campus to hear newly sworn-in President Lyndon Baines Johnson deliver what would become known has his “Great Society” speech.1 President Johnson began his remarks, delivered as the commencement address to the student body, with the imperative to eliminate racism and poverty. He went on to outline his vision for moving “toward the great society,” which would ultimately include federal subsidies for everything from Medicare and Medicaid to a sweeping program of education spending, beginning with preschool and continuing through college.

A June 1965 ceremony for National Head Start Day, front from left: Timothy Shriver, Robert Shriver, Danny Kaye, Lady Bird Johnson, Mrs. Lou Maginn (Director of a HeadStart project in East Fairfield, Vermont), and Sargent Shriver. Red Room, The White House. Photo by unknown photographer, June 30, 1965, courtesy of LBJ Presidential Library.

On April 11, 1965, at the former Junction Elementary School near Stonewall, TX, President Johnson sits alongside his first school teacher, Kate Deadrich Loney, as he signs into law the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. Photo by Yoichi Okamoto, April 11, 1965, courtesy of LBJ Presidential Library.

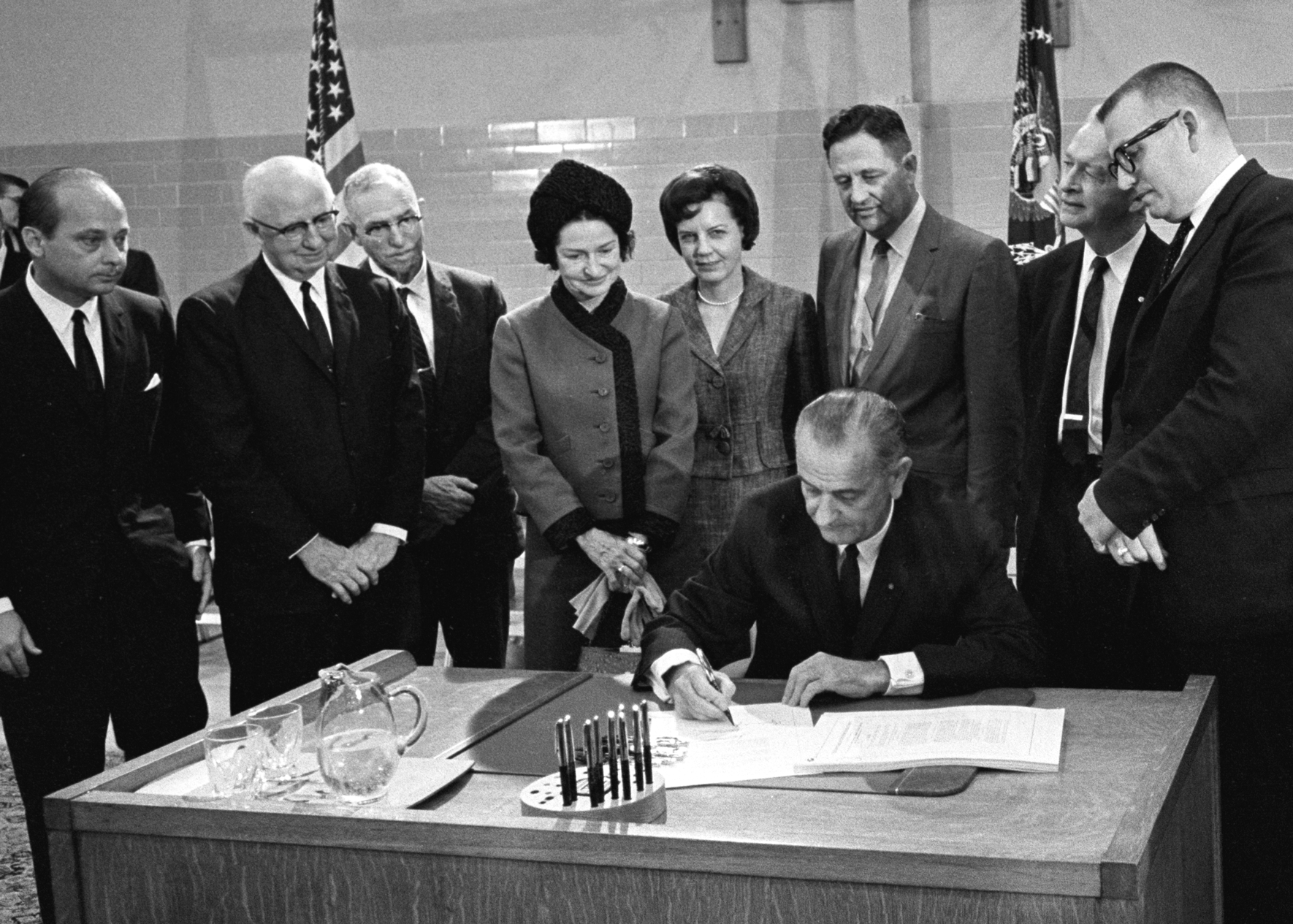

On November 8, 1965, in the gymnasium of his alma mater, Southwest Texas State College, alongside Lady Bird Johnson and other onlookers, President Johnson signs the Higher Education Act of 1965. Photo by Frank Wolfe, November 8, 1965, courtesy of LBJ Presidential Library.

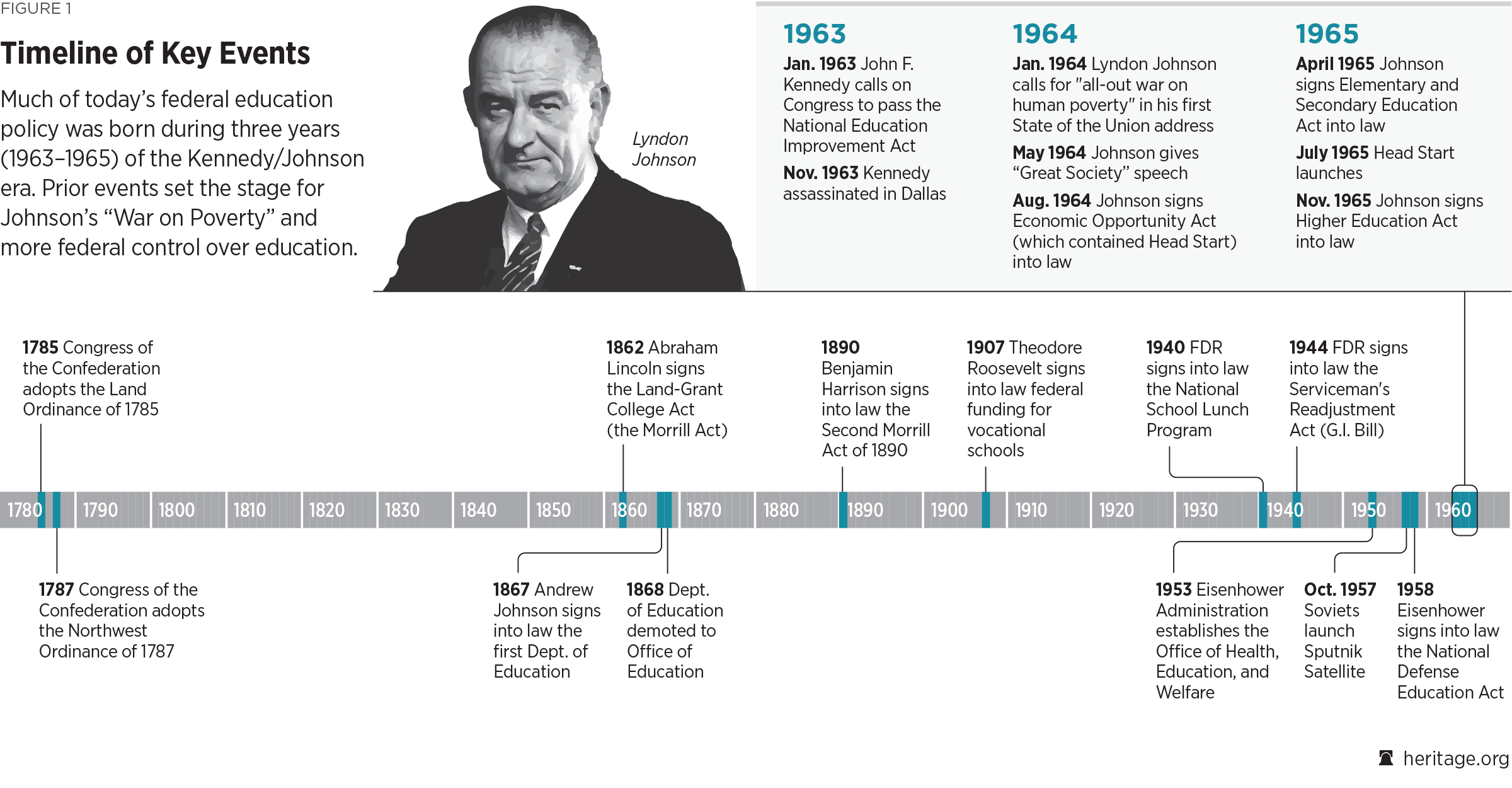

This chapter looks at the creation of the education programs undergirding the Great Society push, including Head Start, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, and the Higher Education Act, putting them in historical context. And importantly, it considers what was a major shift in the very nature of federal involvement in education: a move from education financing as a means to advancing national security interests and fighting a Cold War with the Soviet Union, to fighting a broad “war on poverty” on the domestic front, one-third of which, according to Johnson, would need to be fought in the classrooms of America.

Chapter 2

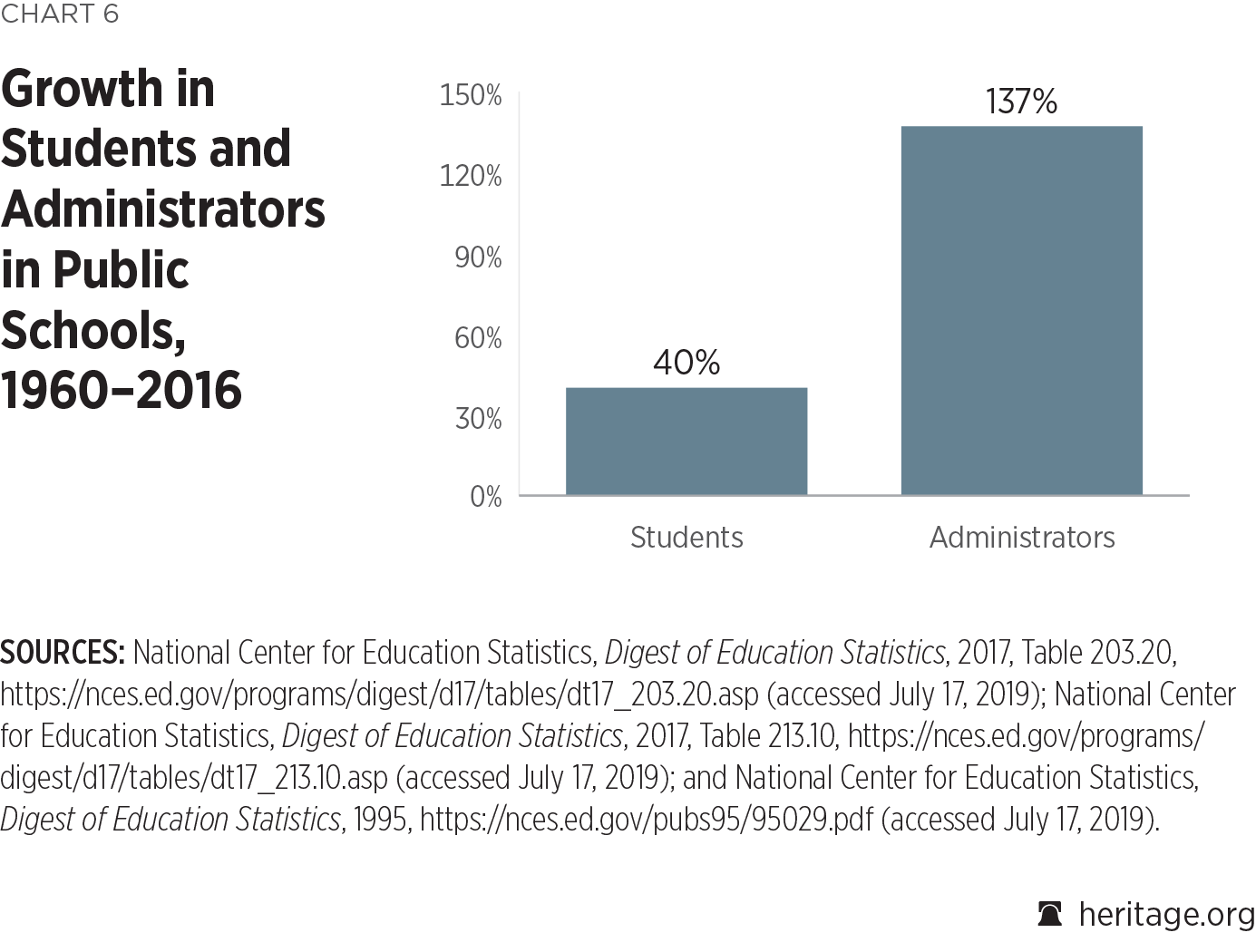

The Productivity Decline in American Public Schools Since the 1965 ESEA: Trends in Spending, Staffing, and Achievement

The passage of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) spawned an era with a tremendous increase in the involvement of the U.S. federal government in America’s K–12 public schools. Between 1964 and 1976, for example, the number of pages of federal legislation affecting K–12 education increased from 80 to 360, and the number of federal regulations increased from 92 in 1965 to almost 1,000 in 1977. Another example of increasing federal involvement in the K–12 public education system is that federal spending on public schools, in nominal dollars, increased almost five-fold between 1960 and 1970, from $651 million to $3.2 billion. The share of public school spending coming from the federal government increased from 4.4 percent to 8 percent over this time period. As of 2016, 8.5 percent of public school revenues came from federal taxpayers.

Chapter 3

The Opportunity Costs of Federal Administrative Compliance Burdens for States and Schools

Since 1965, national policymakers have established federal education laws and programs with the overarching goal of establishing equal opportunity in American education. Congress has enacted laws to assist children who are at risk of being denied equal access to a high quality education, including children from low-income families, children with disabilities, American Indian and Alaska Native children, migrant children, bilingual English-language learners, foster children, and children who are homeless. While the federal government’s share of K–12 education funding remains less than 10 percent,3 five decades of bipartisan federal education policy show sustained national interest in promoting equal opportunity by enabling all children to gain a high-quality education.

Chapter 4

The Fall of Educational Productivity and Policy Paralysis

While there is some small movement up and down over time, the remarkable aspect is that reading and math performance in 2012 looks virtually unchanged from four decades before. Over this time, it is true that the performance of nine-year-olds and of 13-year-olds has improved, but improvements at earlier ages simply have not carried through to the time when students leave school for college and work. This performance would not be a large problem if students were doing extraordinarily well throughout this period. Unfortunately, that is not the case. There are external benchmarks provided by international testing. The PISA results place the U.S. below the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development average in math for 2015—just beating out Greece and falling below Italy and Spain.

Chapter 5

Head Start: Promise and Failures

The early 1960s were a time of national debate about poverty in America. A widely read 13,000-word essay by leftist writer Dwight Macdonald in The New Yorker in January 1963 popularized the 1962 book The Other America: Poverty in the United States, which purportedly laid the groundwork for the War on Poverty. On the heels of J. K. Galbraith’s 1958 The Affluent Society, which contended that poverty in America was no longer “a massive affliction [but] more nearly an afterthought,” socialist author Michael Harrington had penned The Other America, arguing the opposite: that massive poverty was still a reality in America at the time, and that its abatement was not moving as quickly as thought.

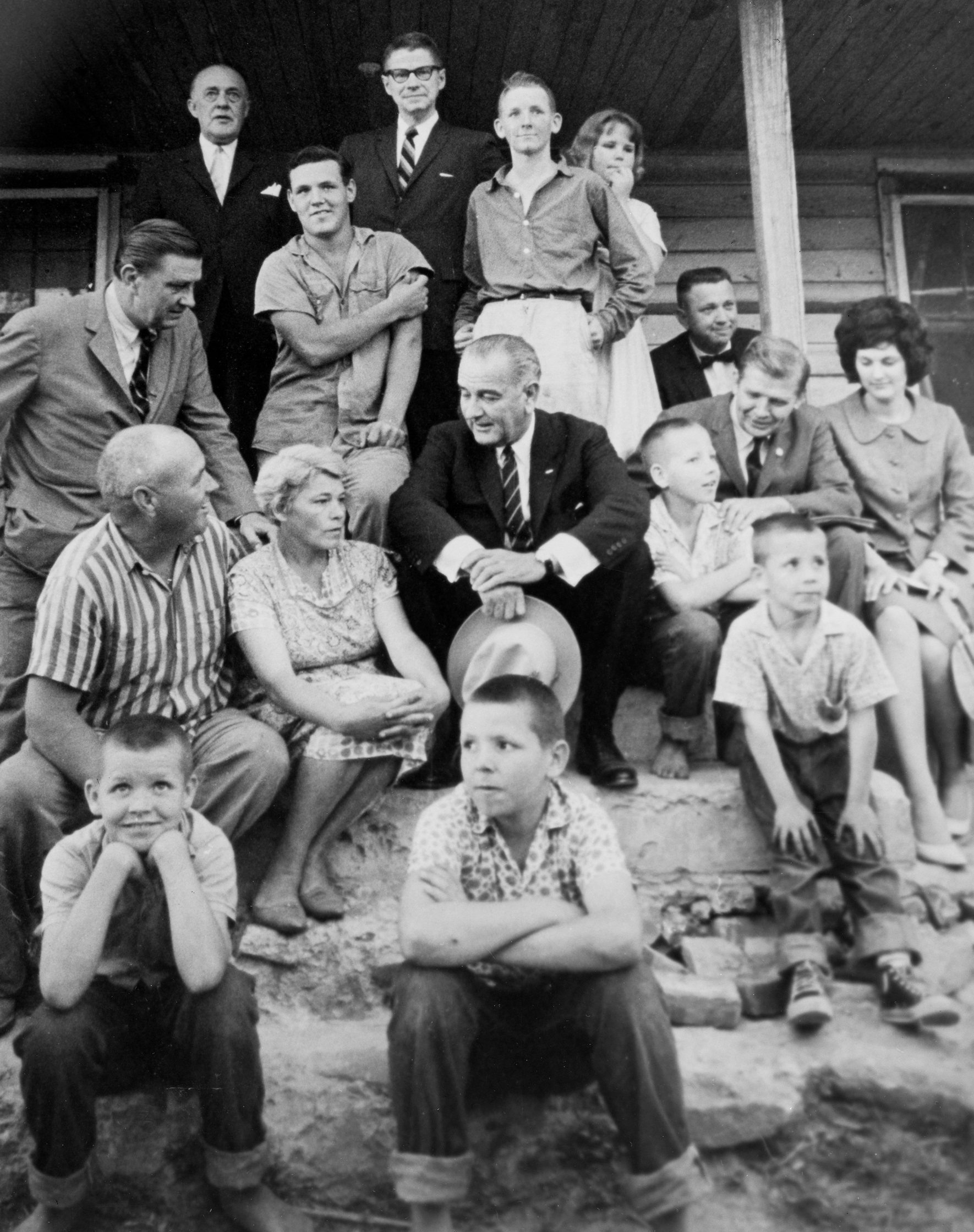

To promote his War on Poverty initiative, President Johnson toured six poverty-stricken Appalachian states including a visit in May 1964 to the home of tenant farmer William David Marlow near Rocky Mount, NC. Photo by Cecil Stoughton, May 7, 1964, courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

The state of poverty in mid-century America had been a concern for President John F. Kennedy, who reportedly crafted his anti-poverty agenda after reading Harrington’s commentary. Walter Heller, Chairman of President Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1961 to 1964, became instrumental in carrying forward President Kennedy’s anti-poverty efforts in the wake of his assassination in November 1963. Heller briefed Lyndon Johnson on a plan that would eventually become the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which included Jobs Corps and education and training programs, including Project Head Start—the focus of this chapter.

Chapter 6

Effectiveness of Preschool: The Research Literature

The effectiveness of pre-K is important for establishing priorities for federal and state budgets, given the intense competition for taxpayer-funded programs—and the critical importance of these developmental years to children’s futures. Programs that are not effective in attaining their objectives must give way to programs that are. This review places major emphasis on recent research and other writings, particularly those following the 2012 publication of the third-grade follow-up of the Head Start Impact Study (HSIS) and a review of related research by this author.

Chapter 7

Support Children, Not Child Care

The first years of life affect human emotional, physical, and psychological development for a lifetime. Everyone wants children well-cared for during these early years so that they are well-adjusted, prepared to learn when they arrive at school, and can grow up to be healthy, functioning, productive members of society.

In hopes of achieving this worthy goal, and in an effort to support working parents, state and federal policymakers have offered or subsidized early learning opportunities and childcare centers. As described in the previous two chapters, governmental preschool and daycare endeavors have yielded disappointing results. Positive impacts tend to be limited to children from disadvantaged backgrounds and even then, those positive effects tend to fade.

Chapter 8

Student Achievement Gap Fails to Close for Nearly 50 Years—It Is Time to Focus on Teacher Quality

The achievement gap in the United States is as wide today as it was in 1971. The performances on math, reading, and science tests between the most advantaged and the most disadvantaged students differ by approximately four years’ worth of learning, a disparity that has remained essentially unchanged for nearly half a century.

In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson announced a war on poverty in which the nation’s education system was expected to play the central role. Since 1980, the federal government has spent almost $500 billion (in 2017 dollars) on compensatory education aid directed toward school districts with large concentrations of low-income students. Another $250 billion has been spent on Head Start programs for low-income preschoolers. Meanwhile, courts have ordered states to equalize funding levels across school districts, thereby shifting still more government resources toward the needs of the socioeconomically disadvantaged. Overall, school spending has tripled over this time period. Yet none of these efforts have altered the size of the socioeconomic status (SES) achievement gap.

Chapter 9

Explaining the Stagnation of America’s Students: The Education Monopoly and Misaligned Incentives

Why is the American education system failing to improve when so many other sectors have seen tremendous increases in productivity over the past half-century? As with any complex system, there are numerous contributing factors, but perhaps the most salient among these is the structure of the public education system itself.

In the United States today, the vast majority of K–12 students attend a government-run school to which they are assigned based on where they live. Because admission to these district schools is offered at no charge (beyond taxes)—and, indeed, is an entitlement for eligible residents— most would-be competition is crowded out, leading to near-monopoly provision of K–12 education. Several unfortunate features of this near-monopoly system impede the fostering of innovation and excellence.

Chapter 10

Classroom Content: A Conservative Conundrum

The content of K–12 education is a minefield for conservatives. Over the past 30 years, education reformers who wanted parents to have choices for their children have tended to focus more on the creation of new public charter schools, or on private school scholarships, than on curriculum and classroom content. They have placed their faith in school choice and the market to create demand for a rich, well-rounded education: Let parents choose and the market provide, and may the best curriculum win.

That faith is largely misplaced. Nearly all—90 percent—of K–12 students in the U.S. attend the public schools to which they are assigned based on their ZIP code.1 Parents and policymakers should also not assume that schools of choice are automatically more sophisticated about curricular content (some are; many are not). There is a foreseeable price to be paid for the reluctance to engage on the foundational question of what the 45 million public school children across the country should know, and leaving it to chance or whim. Doing so risks abandoning the next generation to semi-literacy and, therefore, less than full citizenship. The content delivered in classrooms across the country is a matter that conservatives should not abandon to the Left.

Chapter 11

The Johnson Era: Federal Involvement in Higher Education

Higher Education in America looks remarkably different today than it did 50 years ago. It could be argued that the current structure of American universities can be traced back to three Presidents: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson, and, more recently, Barack Obama. These three Presidents shared a similar governing strategy that involved increased government spending and regulation in the economy. Additionally, each hailed an increased investment in education—specifically higher education—as a significant achievement of their Administration. It is no surprise that the modern Left is now calling for solutions such as “free” public college and student loan forgiveness—a massive federal undertaking.

Prior to the Eisenhower Administration, the federal government had no role in providing loans and grants for students to attend college, and prior to the Roosevelt Administration, provided no major higher education subsidies of any type. In fact, borrowing for college was uncommon until the Johnson Administration.

Chapter 12

Do America’s Universities Undermine the Public Good?

Since the birth of the modern conservative movement in the 1950s, individuals and organizations concerned with civic and liberal education have tried almost everything to reform America’s universities: from William F. Buckley Jr.’s plea for alumni to cease giving money to their alma maters, to funding tenure-track positions, to forming independent centers on campuses that host outside speakers, to organizing external supplementary seminars to make up for what students are not taught in the classroom, to creating new academic departments. Yet 60 years of increasingly sophisticated efforts at reform have largely failed to change the course of America’s universities.

During these decades, many American universities have become the Left’s research and development headquarters, and the intellectual origin or dissemination point for the political and moral transformation of the nation, especially seen in the rolling sexual revolution and the identity politics revolution.

Chapter 13

ls College Worth It? How the War on Poverty Relates to the “Sheepskin Effect” and Upward Mobility in America

In his remarks at the signing of the Higher Education Act (HEA) of 1965, President Lyndon Johnson invoked Thomas Jefferson’s words that “the care of human life & happiness…is the first and only legitimate objective of good government.”1 The point was unmistakable: Federal assistance for students to go to college was an act of caring—it would enable millions to pursue happiness—and no less than Jefferson would agree. But nowhere in the Constitution, from which Washington gets its only (and few) powers, is “education” identified as a matter of federal concern. Nor should it be: It appears federal higher education intervention has launched little happiness, and may have especially hurt the poor.

Jefferson would likely have anticipated this, knowing well the dangers of powerful government. Indeed, Jefferson’s full sentence was “the care of human life & happiness, & not their destruction, is the first & only legitimate object of good government.”2 (Emphasis added.) Jefferson was rejecting “trophies obtained by the blood stained steel, or the tattered flags of the tented field”—war that brought other leaders glory. He was not embracing unfettered government. But it was perhaps fitting that Johnson quoted Jefferson incompletely for an act that wrought very different outcomes than the happiness promised.

Chapter 14

Middle America Pays the Price for War on Poverty Policies—Including in College

Over the past 30 years, the price of attending college in the United States has skyrocketed—having generally tripled at four-year public higher-learning institutions. This cost increase disproportionately affects middle-class families, who end up financing a greater percentage of their education through debt than do their higher-income or their lower-income counterparts. Despite this growing crisis, an ostensibly private, yet federally empowered, regulatory regime discourages boards of trustees—whose duty it is to govern the institutions and who are particularly responsible for fiscal stewardship—from exercising meaningful oversight.

Introduction to Part V

From the “Great” Society to Civil Society

The War on Poverty programs of the second half of the 20th century failed to give children the chance to succeed in school and in life. These programs represent a significant expansion of the welfare state, and accelerated Washington’s change from a government meant to protect liberty to one that tries to solve all societal problems.

Chapter 15

What Is the Purpose of Education?

What is the purpose of education? One might as well ask: What is the purpose of life? These questions are connected because primary and secondary education is preparation for adult life. Education is one of the many things that society does to raise children to be the kinds of people parents and society hope they will become. Since people have legitimate differences about what constitutes a good life and how children can best be raised for that good life, there will be legitimate differences about the content, manner, and goals of education. Just as the U.S. government is committed to respecting different approaches to religion and politics, Americans’ concern for liberty should incline them toward respecting different approaches to education.

Chapter 16

Better Options for Better Preschool: Creating the Conditions for Family Care and Private Providers

The first three to five years of a child’s life are vitally important to the child’s future, as about 85 percent of brain development occurs by age five. It is during this period that children’s interactions— everywhere they go and everyone they see and meet—literally build their brains. Thus, parenting, child care, or preschool are all early childhood education.

Parents are naturally their children’s best advocates. No one cares more about a child’s well-being or knows more about what environment is best for a child than the parents or guardians. That is why parents’ desires should be forefront in any public policy decisions regarding their children’s care and education.

Chapter 17

What Does the Evidence Say About Education Choice? A Comprehensive Review of the Literature

This chapter sets the record straight by reviewing all of the most rigorous evidence regarding private school choice programs in the United States, demonstrating that choice is linked to gains in student test scores, student attainment (high school graduation, college enrollment, college persistence, or college completion), student safety, and student character development (tolerance of others, political participation, voluntarism, charitable activity, crime, or paternity suits).

Chapter 18

Helping Students Succeed in School and Life with Education Savings Accounts

Wealthy families have always had “school choice”—they can move to another school district or send their children to private schools. Over the past 30 years, some 7,000 public charter schools—schools with independent school boards that generally enroll any student who applies, subject to space—have opened around the country to give all students more choices in education, but especially those whose parents cannot find (read: afford) a new neighborhood in which to live.7 More than half of all U.S. states have some form of K–12 private school voucher or other scholarship option—though these options are largely limited to children from low-income families or children with special needs.

Chapter 19

The Classical Charter Movement: Recovering the Social Capital of K–12 Schools

In previous generations, Americans drew social capital from various intellectual authorities, most of whom could be found among the primary sources studied in classical schools. Stretching from antiquity to modernity, the great books of Aristotle, Augustine, Cicero, Descartes, Euclid, Homer, Locke, Shakespeare, and dozens of other canonical works served as the intellectual gold standard for America’s cultural currency.

Unfortunately, over the past century, progressive educational leaders—from John Dewey to David Coleman—have systematically eroded the influence of great books, causing a decisive break with the educational standards of the past. Great works of literature, history, mathematics, and philosophy (many written in Latin or Greek), along with training in the fine arts and the pedagogy of the seven liberal arts, have largely been displaced by contemporary, progressive notions of schooling. Against the perennial, classical approach, progressive education claims a scientific basis for its methods, seeking to construct efficient systems for achieving K–12 literacy and numeracy and to prepare the next generation for success in the marketplace (think “career ready”) and participation in democratic institutions (read: political activism). Replacing great books (classical) education with contemporary “social studies” has become a distinguishing feature of the progressive approach.

Chapter 20

The Homeschooling Advantage: Examining the Research, Exploring the Future of the Movement

As the government grip on education has tightened over the past half-century, more parents are choosing to opt out of conventional schooling in favor of family-centered learning. Homeschooling has grown from a radical act at the time of Johnson’s Great Society to a widely accepted educational option for nearly two million American children. Much has changed in the homeschooling movement since it sprouted from the countercultural Left and expanded through the religious Right. Many families still choose homeschooling for ideological reasons, but the primary catalyst for today’s homeschoolers is the dissatisfaction with the learning and safety environment of government-assigned schools. This chapter traces the history of the modern homeschooling movement from the marginal to the mainstream; highlights current research on homeschoolers’ motivations, practices, and outcomes; and explains how homeschooling is triggering educational innovation and entrepreneurship to bring education freedom to more families.

Chapter 21

A Better Path Forward: Re-Thinking Government Student Loans and Grants

For more than three centuries—from 1636 to 1944—the federal, or earlier colonial, government did virtually nothing to provide direct financial assistance to students attending college.1 Yet the nation’s system of colleges and universities grew to arguably the best in the world, and millions of Americans, many of modest means, graduated. The Serviceman’s Adjustment Act of 1944 (the GI Bill) was designed as a form of deferred compensation for veterans, and was followed in the next decade by the 1958 National Defense Education Act, providing some financial assistance, especially for those pursuing science and engineering careers. But even in 1965, federal student loans totaled a modest $159.2 million—which, after adjusting for inflation, is equal to about one billion dollars in 2019.

Chapter 22

Conserve Free Speech on Campus

Who cares that 20 students at the University of Wisconsin staged a protest in October 2017? Just months earlier, violence broke out at the University of California, Berkeley, after the invitation of a controversial speaker to campus, involving explosives and resulting in some $100,000 in damage to buildings and other facilities. In March, a mob assaulted a Middlebury College professor, sending her to the hospital following a lecture. In May, Evergreen State University cancelled classes and postponed graduation after students occupied administrative buildings and chased a professor into hiding—all of which would make the Wisconsin protest otherwise unremarkable.

Yet the demonstration in Wisconsin has one distinguishing feature that offers hope for the future of academic freedom and the pursuit of truth in the academy. Emotionally charged rallies on college campuses typically do not stop until a scheduled event is disrupted or a building has been occupied. The Wisconsin students, though, said that the University of Wisconsin’s new policies to protect free speech on campus “definitely changed the way” the group acted, according to the school newspaper. The group held a demonstration, but did not delay or disrupt the scheduled event.

Chapter 23

The Comprehensive Conservative Agenda for Restoring Excellence in Education

What is to be done? In education, the first step to improving the quality of pre-K, K–12, and postsecondary learning options is a bold one: eliminating Washington’s involvement. Education in the U.S. should return to its roots from the earliest days of the republic, when parents had a central role in choosing how and where their child learns, then later as state and local officials were the primary policymakers, and if students chose to attend college, they paid their way without making the Faustian bargain of a federal loan.

Conclusion

Conclusion: Restoring Education Excellence in America

As President Lyndon B. Johnson stepped to the podium at the University of Michigan in May 1964 and called for the country to build a Great Society, citing the classrooms of America as one of the pillars of that vision, he lit a federal fuse that ignited half a century of Washington’s ever-growing intervention in education. The spark caught during the John F. Kennedy Administration in the wake of the Sputnik launch. But President Johnson’s declaration that “learning must offer an escape from poverty,” was fostered by a growing national sentiment that poverty in America had become an issue that needed concentrated attention. A seismic shift in the locus of power over educational policy from the states and local communities to the federal government soon followed.

Now, 55 years after President Johnson’s Great Society speech, with more than $2 trillion in taxpayer monies spent on K–12 education—with abysmal results—Americans must sadly echo President Johnson’s refrain: “We are still far from that goal.”

Contributors

Armand Alacbay is Vice President of Trustee and Government Affairs at the American Council of Trustees and Alumni.

Mary Clare Amselem is Policy Analyst in the Center for Education Policy, in the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.

David J. Armor, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

Jason Bedrick is Director of Policy for EdChoice.

Lindsey M. Burke, PhD, is Director of and Will Skillman Fellow in Education in the Center for Education Policy, of the Institute for Family, Opportunity, and Community, at The Heritage Foundation.

Jonathan Butcher is Senior Policy Analyst in the Center for Education Policy, of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.

Corey A. DeAngelis, PhD, is Director of School Choice at the Reason Foundation.

Jay P. Greene, PhD, is the 21st Century Distinguished Professor of Education Policy, and the Chair of the Department of Education Reform, at the University of Arkansas.

Rachel Greszler is Research Fellow in Economics, Budget, and Entitlements in the Grover M. Hermann Center for the Federal Budget, of the Institute for Economic Freedom, at The Heritage Foundation.

Eric A. Hanushek, PhD, is the Paul and Jean Hanna Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University.

Robert L. Jackson, PhD, is Chief Academic Officer of Great Hearts America, and Director of the Institute for Classical Education.

Dan Lips is a Visiting Fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

Carrie Lukas is the President of the Independent Women’s Forum.

Neal McCluskey, PhD, is the Director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom.

Kerry McDonald is a Senior Education Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education, and author of Unschooled: Raising Curious, Well-Educated Children Outside the Conventional Classroom (Chicago Review Press, 2019).

Arthur Milikh is Associate Director of, and Research Fellow in, the B. Kenneth Simon Center for Principles and Politics, of the Institute for Constitutional Government, at The Heritage Foundation.

Paul E. Peterson, PhD, is Senior Editor of Education Next; the Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government, and Director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance, at Harvard University; and a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Michael B. Poliakoff, PhD, is President of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni.

Robert Pondiscio is Senior Fellow and Vice President for External Affairs of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Benjamin Scafidi, PhD is Professor of economics, and Director of the Education Economics Center, at Kennesaw State University.

Richard Vedder, PhD, is Distinguished Professor of Economics Emeritus at Ohio University, and a Senior Fellow at the Independent Institute.

Patrick J. Wolf, PhD, is distinguished professor and 21st Century Chair in School Choice at the University of Arkansas.

Charmaine Yoest, PhD, is Vice President of the Institute for Family, Community, and Opportunity, and the Joseph C. and Elizabeth A. Anderlik Fellow, at The Heritage Foundation.

I predict that all of those of both parties of Congress who supported the enactment of this legislation will be remembered in history as men and women who began a new day of greatness in American society.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson

Remarks on the signing of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in the one-room schoolhouse he attended as a boy, Johnson City, Texas, April 11, 1965.

Existing data do not allow a definitive answer, but a decline in teacher quality, especially of those teachers responsible for the education of disadvantaged students, has almost certainly occurred over this same period of time.”

Paul Peterson, Ph.D.

Harvard University

And where conservatives have grown wary and suspicious of meddling in curricula, activists and advocates on the Left have demonstrated far less reticence about imposing their views, moving further from the unifying impulse undergirding the entire purpose of public education.”

Robert Pondiscio

Thomas B. Fordham Institute

The free market and targeted, choice-based policies are key components to helping families achieve their first choice for child care—whether that be a parent at home or accessible and affordable child care.”

Rachel Greszler

The Heritage Foundation

In all of this, classical schools strive to model excellent thought and practice, such that great ideas are integrated with moral exemplars, where the quality of great books is matched by the caliber of those teaching the books.”

Robert Jackson, Ph.D.

Great Hearts America/Institute for Classical Education

In general, university staffers have benefited more from federal student financial assistance than have the students; students in a sense are a pawn in an elaborate academic rent-seeking exercise.”

Richard Vedder, Ph.D.

Ohio University (Emeritus)

The proposals conserve the idea that the rights to think and speak freely existed before government—and are government’s responsibility to protect.”

Jonathan Butcher

The Heritage Foundation

A third place to build the Great Society is in the classrooms of America. There your children’s lives will be shaped. Our society will not be great until every young mind is set free to scan the farthest reaches of thought and imagination. We are still far from that goal.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson

"Great Society” speech, May 22, 1964

President Johnson, however, left out the most important place in which to foster “great” societies with citizens of character and moral strength: the family.”

Charmaine Yoest, Ph.D.

The Heritage Foundation