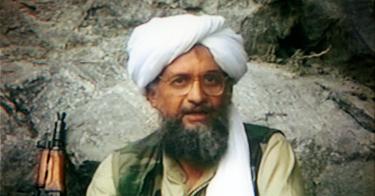

Ayman al-Zawahri, Osama bin Laden’s deputy and a mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks, has been killed in a U.S. drone strike.

The good news is that one of the world’s most notorious terrorists is dead. The bad news is that, one year after the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, Zawahri’s presence in the capital of Kabul confirms fears that the country again would become a safe haven for international terrorists.

For over 20 years, the U.S. government unsuccessfully hunted Zawahri who, like bin Laden, was believed to be in hiding somewhere in Pakistan.

Earlier this year, intelligence revealed Zawahri’s family had moved to a posh neighborhood inside Kabul once used by foreign diplomats. Zawahri later was confirmed to be residing on the premises.

When an opportunity presented itself, the Biden administration approved a CIA operation to strike Zawahri on July 30, likely with two specialized drone-launched Hellfire missiles. A CIA team on the ground reportedly confirmed Zawahri was the only person killed in the strike.

The Taliban denounced the strike, claiming it violated the Doha Agreement that the terrorist group signed with the U.S. to set the terms for the U.S. withdrawal.

Of course, in that same agreement the Taliban pledged to “prevent any group or individual in Afghanistan from threatening the security of the U.S. and its allies, and will prevent them from recruiting, training, and fundraising, and will not host them.” (Emphasis added.)

According to a White House background briefing, senior Taliban figures were aware of Zawahri’s presence in Kabul.

Eliminating one of the world’s most wanted terrorists in an operation with no civilian casualties was an unmitigated victory for the U.S. But the operation—and Zawahri’s presence in Kabul—raises important questions.

The most interesting questions relate to the logistics of the operation and the sources of intelligence: Who tipped off the CIA as to Zawahri’s whereabouts? More interesting, whose airspace was transited to get the drone in position for a strike?

Islamabad insists the Pakistani government was not consulted. Was Pakistani airspace used without the government’s permission? Was a secret deal cut? Or did the drone approach via one of the Central Asian countries with or without their permission?

The far more concerning questions relate to Zawahri’s presence in Kabul, and the nexus between al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and the Haqqani network. When the Taliban marched on Kabul last August, it was quickly evident that the Haqqani network—a hyperviolent terrorist group that predated and later merged with the Taliban—had emerged as the greatest victor of the Afghan war.

Outmaneuvering the traditional Afghan Taliban leadership, Haqqani network leader Sirajuddin Haqqani (son of the group’s infamous founder, Jalaluddin Haqqani) assumed control over internal security in Afghanistan and appointed other Haqqani network leaders to senior posts in the new government.

This was bad news. Throughout the course of the Afghanistan War, the Haqqani network was implicated in the bloodiest and most high-profile terrorist attacks on U.S. and Afghan government targets.

The Haqqani network is also a favored militant group of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Adm. Mike Mullen, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called the Haqqani network a “veritable arm” of Pakistani intelligence and former Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., publicly claimed that the Haqqanis receive protection and medical care inside Pakistan.

The Haqqani network was the first Afghan militant group to embrace suicide bombings and was implicated in the single deadliest attack on the CIA in the organization’s history, as well as multiple attacks on the U.S. and Indian embassies in Afghanistan and an international hotel in Kabul.

After assuming operational leadership of the Haqqani network from his ailing father in the mid-2000s, Sirajuddin published a manifesto advocating global jihad outside Afghanistan’s borders. The Haqqani network ostensibly was overseeing security in the Afghan capital in August 2021 when a suicide bomber killed 13 U.S. military service members and over 170 Afghan civilians at the Kabul airport during the rushed U.S. withdrawal.

Now, take a guess where Ayman al-Zawahri was residing in Kabul? He was in a guest house owned by Sirajuddin Haqqani.

This was foreseeable. In the 1980s, Jalaluddin Haqqani was a key figure in recruiting Arab militants from the Persian Gulf to join the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda’s first training camp was established in Haqqani network territory in Pakistan.

This is why I was deeply concerned about the possibility of an al-Qaeda resurgence after the Taliban-Haqqani takeover of Kabul last August.

In an article I published in November in War on the Rocks, I reviewed how virtually every independent assessment—including from the U.S. government, the United Nations Security Council, and independent researchers at Stanford—had all concluded that the Taliban, and especially the Haqqani network, maintained strong and growing links to al-Qaeda. It was, I wrote, “highly unlikely they will cut ties.”

In 2020, the U.S. Treasury Department concluded that al-Qaeda and the Haqqanis were discussing forming joint units of armed militants. The following year, a U.N. report described the Haqqanis as a “the primary liaison between the Taliban and al-Qaeda.”

In August 2021, President Joe Biden peculiarly claimed that al-Qaeda was “gone” from Afghanistan. But two months later, a senior Biden administration official testified before Congress that not only was al-Qaeda still in Afghanistan, it had the will and was generating the capability to conduct terrorist attacks on the U.S. and its interests abroad.

Again, the good news is that the strike killing Zawahri demonstrated that the U.S.—even after a full withdrawal from Afghanistan, even with Pakistan-U.S. relations in a dysfunctional state, even without formal overflight arrangements with neighboring countries—still enjoys the capability to strike high-value targets in Afghanistan, thanks in large part to the tireless work of the U.S. intelligence community.

The bad news is that the Taliban faction governing Afghanistan today is even more operationally and ideologically aligned with al-Qaeda than the old Afghan Taliban leadership.

The presence of the man who was arguably the world’s most notorious terrorist in a Haqqani-owned safehouse in Kabul only confirms fears that Afghanistan may yet again become a safe haven for international terrorists.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal