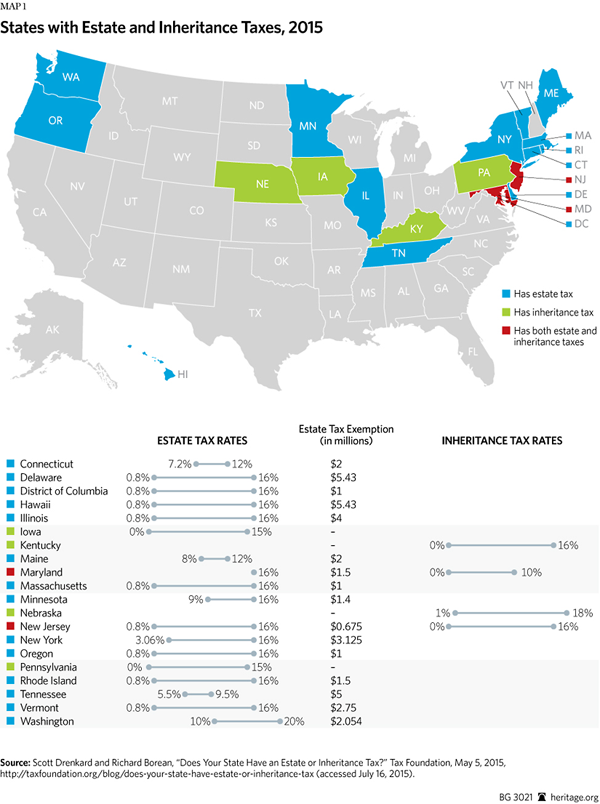

Over the past five years, a handful of states—Indiana, Kansas, Ohio, Oklahoma, North Carolina, and Tennessee—have repealed their death taxes mostly in response to changes in the federal tax treatment of estates, which no longer make it free for states to impose their own death tax. Two more—Maryland and New York—have enacted legislation that will gradually raise their state estate tax exemptions to the federal level by 2019, thereby reflecting the new federal tax regime. In recent weeks, legislation has been proposed in Delaware to eliminate the estate tax as revenues significantly lag predictions. In the meantime, the 13 states that still impose death taxes continue to see a significant outmigration of people and resources, a trend likely to continue. From 2005 to 2014, only five of these states realized net positive domestic migration. Even more telling, nine of the top 10 states in domestic migration imposed no estate or inheritance tax.[1] Every state would be economically wise to eliminate this tax because it impedes growth and leads to an exodus of wealth from the state.

State Death Taxes

Prior to 2001, states could impose an estate tax of up to 16 percent with no extra burden on their residents because a federal tax credit offset state estate taxes. In other words, regardless of whether or not a state imposed an estate tax, a federal tax on estates above a certain level would be paid. The only question was whether those tax proceeds would flow to the federal government or to the state. In the absence of a state estate tax, up to 16 percent of the estate valuation would flow to the federal government. However, a state could impose a tax of its own. Every dollar owed to the state government as a result of this tax could be deducted from the tax owed to the federal government.

But that policy has ended. Now state death levies are paid out of the deceased’s assets rather than diverted from the amount due to the federal government. The only federal tax break related to estate taxes is a tax deduction in the amount of the state estate tax imposed. This tax deduction lowers the valuation of the estate for federal estate tax purposes by the amount of the state estate tax paid. For estates incurring state estate tax liability but falling beneath the federal threshold, this tax deduction does not save an estate a single dime.

As a result of the elimination of the state estate tax credit, the estate tax is no longer “free” to states. Other than the savings resulting from state estate deduction, every dime collected is in addition to any federal estate tax owed.

Furthermore, the amount of an estate “exempted” from taxation at the federal level has risen drastically from $1,500,000 in 2005 to $5,430,000 in 2015. However, not all states have followed suit. For instance, in Nebraska, an estate tax of up to 18 percent must be paid on estates worth as little as $10,000. Simply put, dying in certain states is far more expensive than in others.

Regrettably, state legislators often badly misunderstand the estate tax rules, which might explain why most states with death taxes still apply a 16 percent rate—as if federal rules had not changed. These 13 states and the District of Columbia still impose huge costs on their own citizens at death and thus chase out capital, jobs, and wealthy residents by failing to modernize their state estate tax laws.

The estate tax is an unfair double tax on income that was already taxed when it was earned by the person who leaves an estate for his children. But the estate tax is not just unfair—it kills jobs and incomes. Many studies indicate that the death tax is so inefficient, so adverse to saving and capital investment, and so complicated that the states and the federal government would actually recoup much, if not all, of the revenues lost from repealing this tax through higher tax receipts resulting from long-term economic growth.

For example, a 1993 study by George Mason University economist Richard Wagner suggests that the death tax causes so much economic destruction in capital formation that states and the federal government would enhance their revenue collections over the long term without the tax.[2] A 2001 study for the American Council for Capital Formation co-authored by Douglas Holtz-Eakin, later head of the Congressional Budget Office, and Donald Marples, later senior economist for the U.S. Government Accountability Office, highlights the negative impact of the estate tax:

Entrepreneurs are particularly hard hit by the estate tax as they face higher average estate tax rates and higher capital costs for new investment than do other individuals.… The estate tax causes distortions in household decision-making about work effort, saving, and investment (and the loss of economic efficiency) that are even greater in size than those from other taxes on income from capital.[3]

States Losing Income and Revenue as Residents Move to Avoid Death Taxes

A 2004 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that states lose up to one-third of their estate taxes because “wealthy elderly people change their state of residence to avoid high state taxes.”[4] That was before the change in federal law when states imposed effective estate tax rates that were only one-third as high as they are now. Under the new soak-the-rich schemes, some states could lose so many wealthy seniors that they may actually lose revenue over time. Not surprisingly, it is generally the liberal, tax-and-spend blue states that are reinstating taxes on death. Over the past 10 years, nearly 1,000 people every day have fled these high-tax states for low-tax states. This is one reason the Northeast has suffered economically and declined politically in terms of electoral votes.

State Death Tax Rules

The worst state for dying is Minnesota. In 2013, it enacted a 10 percent gift tax with a $1 million exemption. A gift tax is a levy on money given away while still alive. This tax is in addition to Minnesota’s 16 percent estate tax. The new law is even more punitive because it applies the 16 percent estate tax (6 percent on top of the earlier 10 percent gift tax) to any gift within three years of death.

Numerous studies, including one by President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of the Treasury Lawrence Summers,[5] suggest that the desire to leave a legacy for one’s heirs—rather than just enjoy a comfortable retirement—incentivizes many to continue to invest in their enterprises and save money throughout their entire lifetime. According to Summers et al.,

The evidence presented in this paper rules out life cycle hump saving as the major determinant of capital accumulation in the U.S. economy. Longitudinal age earnings and age consumption profiles do not exhibit the kinds of shapes needed to generate large amount of life cycle wealth accumulation. The view of U.S. capital formation as arising, in the main, from essentially homogenous individuals or married spouses saving when young for their retirement is factually incorrect.

Intergenerational transfers appear to be the major element determining wealth accumulation in the U.S.[6]

In other words, this desire to leave a legacy accounts for much of the trillions of dollars of wealth passed from one generation to the next. All of society benefits when this wealth remains invested in the productive economy rather than being siphoned into the coffers of inefficient government agencies. Yet the higher the death tax rate, the more this incentive for wealth creation—and legacy creation—is reduced. The combined federal and state death tax rate now approaches 50 percent in many states (after accounting for deductions). This explains why estate tax planning and tax avoidance is a booming industry.

State death taxes are especially futile because residents subject to the tax can avoid it by relocating before they die. No less an ardent liberal than the late Senator Howard Metzenbaum (D–OH), one of the wealthiest Members of Congress, moved to Florida from Ohio after he retired from politics, thereby avoiding millions in estate taxes. For example, a successful New York business owner with $50 million of lifetime savings can move his family and company to Florida, Georgia, Texas, or 28 other states and cut his death-tax liability by more than $7 million.

States That Tax Death

Below are a few examples of how state death taxes are affecting state economic conditions.

Minnesota. Thousands of Minnesota snowbirds move to Florida during the winter months already, so the new tax adds an extra financial incentive not to return. The Center for the American Experiment, a Minnesota research group, found that $3 billion of income was lost to the state between 1995 and 2010 because Minnesotans relocated to Florida and Arizona.[7]

The think tank’s conclusion should be required reading for policymakers in every state still imposing a death tax: “If enough people move away and stop paying Minnesota taxes, then Minnesota could very well experience a net revenue loss due to the estate and gift tax.”[8] This will mean that people making less than $1 million a year will be left paying the tab. Minnesotans already have a strong incentive to become snowbirds and flee because of the cold winters. Now they have two reasons to leave.

New York. In his 2014 State of the State Address, New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo (D) said:

New York is one of only fifteen states with an estate tax and our exemption levels are among the lowest and our rates are among the highest. Let’s eliminate the move-to-die tax where people literally leave our state, move to another state to do estate tax planning. We propose raising New York’s state tax threshold and lowering the rate to put it into line with other states.[9]

Governor Cuomo stated a fundamental economic truth: The death tax levied by states is a primary and underestimated killer of both jobs and businesses. He is spot on that wealthy people do move themselves and their businesses from high-death-tax to low-death-tax states, especially as they grow older. Although New York is now gradually raising the estate tax exemption levels, its 16 percent tax on estate values exceeding this limit is still higher than in the 31 states that have no death tax, whether estate or inheritance.[10]

In New York City, about 40 percent of income tax revenue comes from those earning $1 million or more, according to the latest data (2011) from New York City’s Independent Budget Office.[11] Yet a New York Sun report found that “it has been typical for New York to lose wealthy residents to so-called ‘retirement states’ with warmer climes and more hospitable tax systems.” Estate tax lawyers told the Sun that “the costs of the state estate tax outweigh the benefits…because of loss of income and sales tax receipts as well as the economic loss engendered by the wealthy fleeing the state.”[12] A rational policy for Albany would be to lay down a red carpet to encourage more rich people to move to New York or at least to stay. Instead, with its 16 percent estate tax, Albany politicians have effectively declared: “Invest anywhere but in New York.”

Connecticut. Connecticut is another case study. In 2008, the Connecticut Department of Revenue surveyed 166 estate tax planners, attorneys, and tax accountants in the state and found that 53 percent of their clients leaving Connecticut cited the state’s estate tax. For three of four leaving the state, the estate tax was mentioned as at least a partial reason for leaving. The department estimated that the state lost $1.2 billion in income annually from 2002 to 2006.[13]

The New York Post ran an Associated Press story in February 2015, reporting the state is so dependent on tax revenue from high-income individuals that “Connecticut tax officials track quarterly estimated payments of 100 high net-worth taxpayers and can tell when payments are down.” According to Kevin Sullivan, the state’s commissioner of revenue, “There are probably a handful of people, five to seven people, who if they just picked up and went, you would see that in the revenue stream.”[14]

Scott Frantz, the ranking Republican on the state senate finance committee, said that the state’s dependence on tax revenues from the super-rich is “pretty frightening.”[15] A Gallup Poll in 2014 found that 49 percent of Connecticut residents would leave the state if they could. That was second only to Illinois.[16]

New Jersey. “The average income coming into New Jersey is approximately 50% less than the income that is leaving,” according to a report by the wealth management firm RegentAtlantic. In fact, in the period studied (2009–2010), just five states accounted for 86 percent of this lost income: Florida, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Maryland, and Virginia.[17]

In part, this is due to New Jersey’s dubious status as one of only two states to impose both an estate and a gift tax. Estate values over $675,000 are hit with a 16 percent death tax. RegentAtlantic’s report quoted Sandra Sherman, a partner at Riker Danzig Scherer Hyland Perretti, LLP, noting this “means that if you have a small pension and you have a house in Morris County you are very likely over that limit.”[18]

RegentAtlantic’s New Jersey Wealth Index dipped below 50 in early 2008—indicating a below-average environment for wealth creation—and has eclipsed this pivotal level since.[19]

As RegentAtlantic summarizes, “When it comes to estate taxes, New Jersey or any other state does not compete with the federal government. Instead, the competition takes place on a state-by-state level. Those states with the highest exemption, or no estate taxes, tend to be more attractive to high-net-worth households.”[20]

Rhode Island. According to the Ocean State Policy Institute, from 1995 to 2007, Rhode Island “collected $341.3 million from the estate tax” while it lost $540 million in other taxes “due to out-migration.”[21]

The most significant driver of out-migration is the estate tax, especially considering that the number one destination state for former Rhode Island residents is Florida, a state with no estate tax (or individual income tax).

It is no surprise that after Florida’s estate tax disappeared in 2004, the level of Rhode Island’s out-migration significantly accelerated. In fact, almost $900 million of all income lost (of the $1 billion total) due to out-migration happened after 2004, of which over $400 million went to Florida.[22]

Tennessee. One of the most thorough studies on the impact of estate taxes on migration patterns was conducted in 2012 by the Laffer Center for Supply-Side Economics and Beacon Center of Tennessee.[23] The report compared tax returns in Tennessee with those in other states without an estate tax. The study found before the state enacted legislation terminating the tax, effective January 1, 2016:

Tennessee’s gift and estate tax is the poster boy for bad tax policy. Tennessee is one of only 19 states with a separate estate tax and one of only two states with a gift tax. Tennessee has the single lowest exemptions for both its estate tax and its gift tax.

…

The cost Tennessee has paid for its gift and estate tax in lost economic growth and employment is staggering. Had Tennessee eliminated its gift and estate tax 10 years ago, Tennessee’s economy would have been over 14% larger in 2010 and there would have been 200,000 to 220,000 more jobs in the state. And, the more robust economic growth would have benefited state and local government revenues adding between $7 billion and $7.3 billion to state and local coffers.

…

The average taxable estate in Tennessee is consistently smaller than the U.S. average. In 2010 the average size of a federal estate filed in Tennessee was almost 25% smaller than the U.S. average federal estate, or $1,350,000 less. And, in Tennessee there were over 20% less federal estates filed per 100,000 population than the U.S. average. People really do leave Tennessee because of Tennessee’s gift and estate tax—and they leave in droves.[24]

Estate Taxes Do Not Raise Revenues or Reduce Inequality

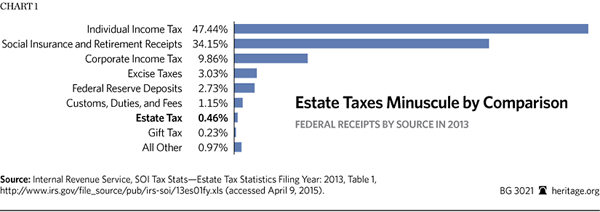

The estate tax is not just immoral and economically harmful. It fails to raise money for the government, or at most it raises a trivial amount.

The latest tax collection data from the IRS make an overwhelmingly persuasive case for eliminating the death tax at the federal level. The federal government would almost certainly collect more revenue if this tax did not exist and if it eliminated the “angel of death” provision of the capital gains tax and then taxed the full appreciation of asset values at the time of sale.

The latest IRS data show that the estate tax raised less than $13 billion in 2013.[25] This is out of nearly $3 trillion in total federal tax collections that year. In other words, a trivial less than 0.50 percent of federal tax receipts came from this tax—less than 50 cents of every $100.[26] Its impact on the federal deficit would be minuscule. If Congress eliminated the tax entirely, the federal government at worst would still collect 99.5 percent of all federal revenues.

This brings us to the stupendous inefficiency of the tax. In 2013, only 4,687 estates paid any federal estate tax.[27] This was about one-fifth of a percentage point of all deaths that year, about two out of every 1,000.[28] Yet nearly every medium-sized estate must waste time and money filling out catalogs of tax forms. The joke in legal circles is that we have an estate tax not to raise money, but to create jobs for thousands of accountants and lawyers.

Most of the billionaire households—e.g., Gates, Buffet, and Rockefeller—will pay almost no estate tax. In the case of Gates and Buffet, billions of dollars of their wealth is sheltered from the IRS through the creation of tax-exempt entities, such as the Gates Foundation. In many cases the income parked there will never be taxed—either while they are alive or after they are dead—thanks to this mother of all tax shelters.

Conclusion

Estate taxes are economically self-defeating. Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz, who served as chairman of Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, once found that the estate tax may increase inequality by reducing savings and driving up returns on capital.[29] Former Clinton Treasury Secretary and Obama economic adviser Larry Summers co-authored a 1981 study finding that the estate tax reduces capital formation.[30] In addition, a 2012 study by the Joint Economic Committee Republicans showed that the estate tax has reduced the capital stock by approximately $1.1 trillion since its introduction nearly a century ago.[31]

This explains why more socialistic nations, such as Sweden and Russia, have abolished their inheritance taxes in recent years. They concluded the tax was economically counterproductive. At the state level, death taxes are self-defeating because they drive out businesses and high-income residents. Even for those choosing to remain in death tax states, the elderly are incentivized to spend down their assets while alive or to find tax shelters, which results in massive disinvestment in family-owned businesses—the backbone of the local economies.

Of course, in America, preventing a state government from confiscating 10 percent to 20 percent of a lifetime estate is easy to do and financially prudent. The person simply needs to move to a state without death taxes. The wonder is not that so many people of wealth leave a state to avoid the estate tax, but that some still have not. One reason to suspect that outmigration from high-estate-tax states will accelerate in the future is that tens of trillions of dollars of wealth will be passed on from one generation to the next over the next two decades. It is no accident that the high-flying states in America are almost all death-tax free.

—Stephen Moore is Distinguished Visiting Fellow in the Project for Economic Growth, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation. Joel Griffith is a Research Associate in the Project for Economic Growth.