Fundamental tax reform remains a top agenda item for many in Congress, especially for House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R–WI) and Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R–UT). The country needs fundamental tax reform because the tax code is stifling economic freedom and preventing the economy from being vibrant and prosperous. Fundamental tax reform would alleviate the harm caused by the tax system and could realistically increase the size of the economy by up to 15 percent over 10 years.[1] Few economic policy initiatives offer a better chance to improve the incomes of all Americans and enhance economic opportunities. Congress should pursue fundamental tax reform.

Regrettably, there is little reason to believe that the White House will be a willing partner in pursuing tax reform. President Barack Obama has never indicated that he wants to fundamentally reform the entire tax code, nor has he shown any willingness to lead such an effort. In practice, presidential leadership has proved vital for successful tax reform.

However, President Obama has said that he would like to reform only the corporate side of the tax code. In fact, he quietly released a framework for such a plan in 2012.[2] Since then he has done little to push the plan through Congress, except to include it in his past two budgets. The details of the framework are problematic,[3] but it at least shows that the President is willing to consider the issue.

Chairmen Ryan and Hatch as well as other leaders in Congress have expressed willingness to reform the business side of the tax code as a first step to full tax reform. However, before Congress undertakes this difficult endeavor, Members of Congress need to have the proper goal in mind of what the completed plan should look like.

The Necessity of Business Tax Reform

Before reforming business taxes, it is useful to understand why reform of the current system is necessary. Traditionally, the impetus for tax reform has originated from concerns about the individual side of the code. Today, the most important purpose of tax reform is to reform the antiquated business tax system because it is a major impediment to achieving prosperity, economic growth, and higher real wages.

High Tax Rate. The biggest problem with the business tax system is the high tax rate. The U.S. corporate tax rate exceeds 39.1 percent when including the average rate of the states.[4] (The federal rate is 35 percent and the states add an average of more than 4 percentage points.) The U.S. corporate tax rate is the highest rate among the developed nations, defined as the 34 members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The average OECD corporate tax rate is 25.3 percent, placing the U.S. substantially above the norm.[5]

Pass-through entities, usually smaller firms, are subject to tax rates as high as 43.4 percent just at the federal level, although they are not subject to tax at the entity level. In 2011, pass-through entities employed more than 50 percent of the private-sector workforce and earned 64 percent of all business income.[6] According to IRS data, there were 3.2 million partnerships, 4.2 million S corporations, and 1.6 million C corporations in 2011.[7]

These high rates discourage investment in the U.S. businesses by both U.S. and foreign businesses. Less investment in the U.S. means fewer jobs and lower wages for U.S. workers.

Worldwide Tax System. In addition to high rates, the U.S. is effectively the only major developed country that uses a worldwide tax system to tax its businesses on the income earned abroad. Most other countries use a territorial system that taxes businesses on only the income that they earn within the country’s borders. The other six OECD countries that use a worldwide system are Chile, Greece, Ireland, Israel, South Korea, and Mexico. Yet each of these six countries has a top corporate income tax rate that is lower than the U.S. rate, making their worldwide systems less economically damaging than the U.S. worldwide regime.[8]

The worldwide system in the U.S. coupled with the high tax rate means that U.S. businesses pay an extra tax on income that they earn abroad. This extra tax reduces the foreign investment that they are willing to make. This reduces jobs and wages for U.S. workers both because U.S.-owned foreign corporations are more likely to buy from the U.S. and because U.S.-headquartered companies create jobs in the U.S. when they have successful foreign operations.[9]

In the mid-1980s, the U.S. business tax system was in line with international norms. The rate was competitive, and other countries taxed their businesses on a worldwide basis. However, in the roughly 30 years since, other developed countries have aggressively cut their rates and moved to territorial systems because of the tremendous benefits that these policies create for their economies.[10] By standing still during those years, the U.S. has fallen behind. It now has an anachronistic business tax system that is ill suited for the modern global economy.

Cumbersome Depreciation System. The cumbersome depreciation system for capital investments in the U.S. tax code adds to the uncompetitive business environment. The U.S. capital cost recovery system is much worse than the OECD average.[11]

The concept of depreciating assets wrongly leaked into the tax code from financial accounting, which is concerned with determining the financial value of a business. Tax accounting should not necessarily follow the conventions of financial accounting.

When accounting for the capital expenses for tax purposes, businesses should be able to deduct the full cost of assets at the time they purchase them. This is known as expensing. Anything short of expensing, such as current depreciation rules, raises the cost of capital and creates a bias against investment by forcing businesses to delay deducting their capital expenses,[12] sometimes for as long as 39 years.[13] This creates cash-flow problems and, because of the time value of money, makes investments in plants, machinery, equipment, and structures more costly. Higher capital costs reduce investment, therefore reducing the productivity of American workers, slowing economic growth, and harming the competitiveness of U.S. businesses. Furthermore, the artificial depreciation timelines created by Congress can tilt the market in favor of some forms of capital and against others, leading to a less efficient allocation of capital and a smaller economy.

Three Phases to Achieve the Best Business Tax System

Assuming a tax on businesses is necessary, the best business tax system that Congress could establish is a cash-flow tax, also known as an inflow-outflow tax.

A cash-flow tax starts with a business’s gross receipts and allows deductions for all business expenses, including the cost of labor, inputs, and capital investment when the business incurs the expenses. If properly structured, such a tax would eliminate the double taxation of business income. A flat tax rate applies to the remaining income, preferably one that would be competitive with other developed nations.[14]

The Heritage Foundation’s New Flat Tax would establish a cash-flow tax.[15] A cash-flow-type tax can also deny a deduction for labor costs to allow for a significantly lower rate, therefore taxing labor and capital factor incomes equally at the business level rather than just taxing capital income at the business level. This variation is known as a business-transfer tax.[16]

Transitioning to such a system would take time given the political and practical difficulties. Therefore, this paper establishes a three-phase pathway to reforming the business tax code that would go a long way toward simplifying the current system, improving its fairness, and promoting job growth and economic prosperity in America.

Phase 1: Achievable Reforms That Would Begin Unleashing Growth

The business tax system inhibits economic growth, job creation, and wage increases because it levies the highest corporate tax in the world, denies full expensing for business investment, and taxes the foreign earnings of U.S. businesses. Congress should first seek to ameliorate the pain caused by these problems with immediately achievable policies.

Specifically, Congress should:

- Lower the corporate tax rate. The U.S. tax rate of approximately 39 percent is the highest among OECD countries. This high rate is likely the heaviest drag on the economy in the entire tax code. It greatly curtails domestic investment by both U.S. and foreign firms. Lowering the corporate tax rate would greatly improve the economy and job and wage growth for American families.

President Obama’s business reform plan sets the corporate rate at 28 percent. Although that is still too high, it would be better than the current rate and would be a first step to lowering the rate enough to re-establish the competiveness of U.S. businesses in the global economy. It could serve as a starting point for negotiations between Congress and the President. - Tax pass-through and C corporations at the same rate. A potential pitfall to business tax reform is the disparity between the rates that C corporations and pass-through businesses pay. Pass-through entities are subchapter S corporations, limited liability companies (LLCs), and partnerships that do not pay income tax at the entity level. Instead, the owners of the business must report the entity’s income on the owners’ individual tax returns. Sole proprietorships also pay business income taxes on their individual tax returns.

C corporations pay the 39 percent combined federal and state corporate tax rate. Pass-throughs pay the individual rate 39.6 percent at the federal level, plus state income tax rates. Pass-throughs also pay an Obamacare 3.8 percent surtax. When all these taxes are added together, some pass-through businesses pay nearly 50 percent in many states—far in excess of the rates that C corporations pay.[17]

If business tax reform lowered the corporate rate and made no changes to the treatment of pass-throughs, it would greatly exacerbate this already large inequity. Instead, they should be taxed at the same rate.

An additional risk for pass-through businesses is that business tax reform would broaden the business tax base that applies to both C corporations and pass-throughs, but only reduce the C corporation tax rate. This would constitute a large tax increase on pass-throughs, which are often small or start-up companies that are the source of most job creation.

In principle, business tax reform should equalize the rates that all businesses pay and eliminate the double taxation of business income. There are two basic ways to accomplish this result. First, all businesses could be taxed at the entity level and subsequent payments in the form of dividends or distributions from the business to its owners could be free of additional tax.[18] Second, all business entities could be treated as pass-through entities. In general, however, entity-level taxation is administratively more appropriate for larger firms with widely held ownership in which shares are traded often. Pass-through status is more appropriate for closely held businesses in which ownership changes are less frequent.[19] An identical rate for both types of businesses could be established while still adhering to this principle. - Lower taxes on the foreign income of U.S. businesses. President Obama and former Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee Dave Camp (R–MI) both recognized the harmful effects of worldwide taxation, and both included lower rates on certain types of foreign income in their respective business tax-reform plans. President Obama proposed taxing such income at 19 percent in his most recent budget.[20] Camp proposed a 15 percent rate. Whether Congress adopts a rate in this range or a lower rate on all overseas earnings, as long as the foreign tax credit and deferral are maintained, a reduced rate would be a positive step toward a territorial regime and would spark a surge of domestic investment.

Members of Congress have discussed changing the tax treatment of the untaxed foreign earnings of U.S. businesses without fixing the current broken system of international taxation. Some want to lower the tax rate on this income so that businesses will bring it back, either to generate extra revenue to pay for new spending or to spur economic growth. Both justifications are highly dubious.[21]

Given the interest in changing repatriation policy, Congress will likely revive the issue if it embarks on business tax reform. The approaches outlined above are intermediate and would not fix the problems caused by the worldwide system going forward. Congress should change repatriation policy only as part of tax reform that creates a true territorial system that permanently addresses the problems. An intermediate business plan that does not move toward a true territorial system should not include repatriation changes. - Make bonus depreciation permanent. “Bonus depreciation,” more precisely referred to as 50 percent expensing, allows most businesses to deduct 50 percent of most of their capital purchases in the year in which the businesses purchased them. This provision has been law for several years. Allowing it to lapse would move cost-recovery policy in the wrong direction and constitute a substantial tax hike. Congress should improve certainty and solidify the improvement by making 50 percent expensing permanent. This would substantially reduce the cost of capital and would increase investment, productivity, and real wages.

Phase 2: Good Governance

Once Congress makes the changes in Phase 1, it should repair parts of the business tax system that have long needed shoring up. These policies will not have as much positive impact on economic growth as those in Phase 1, but they are important aspects of the current system that hurt economic growth and that Congress has left unaddressed for too long.

Congress should:

- Eliminate unjustified corporate tax preferences. The corporate tax code has many economically unjustified tax preferences, although not as many as is commonly assumed. Notably, provisions that allow businesses to deduct their capital expenses are not tax preferences. Most true tax preferences are provisions used by individuals. Nevertheless, Congress should eliminate these unjustified business tax preferences because it is good policy and will improve economic efficiency.

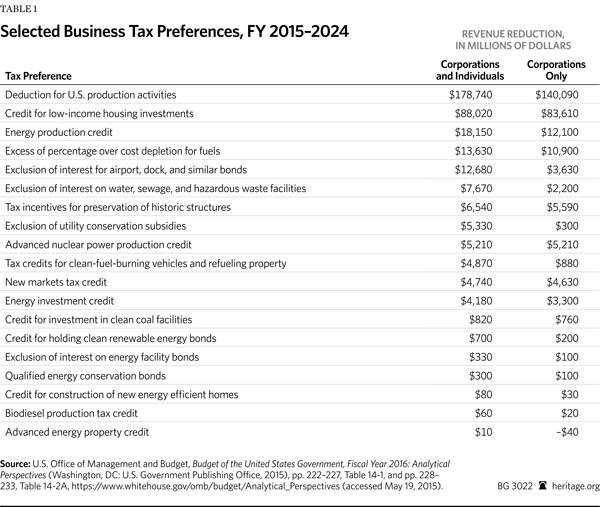

Eliminating business tax preferences would help to offset a portion of the cost of pro-growth advancements on the business side of the tax code. As such, their elimination should not be construed as a tax increase. Yet even eliminating all of the tax preferences listed in Table 1 is unlikely to offset the entire cost of pro-growth policy improvements, especially as scored on a static basis by the Joint Committee on Taxation. Eliminating all of the genuine tax preferences would fund only a small reduction in the corporate rate.[22]

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), tax receipts will comfortably exceed their historical average over the next decade.[23] There is room for a tax cut, especially if in the long run it proves to be small or non-existent on a dynamic basis and would substantially improve economic growth, job creation, and real wage growth.

When Congress fully establishes a cash-flow system, scrapping unnecessary business tax preferences will not raise enough to offset the entire amount of lost revenue on a static basis. It is important that Congress accept a business tax cut as the price of reversing its policy of forcing American businesses to operate under the least competitive tax system in the industrialized world. Such a tax system would create a strong dynamic feedback for revenues because it would markedly improve economic growth and the incomes and opportunities for all Americans. Both factors should make Congress much more amenable to a business tax cut.

- Retirement account simplification. Few small employers offer retirement accounts because of the complexity, high compliance costs, and regulatory risks.[24] This makes it more difficult for them to attract employees and more difficult for small business owners and their employees to save for retirement. This is one of the most complex areas of the tax law and desperately needs simplification.[25]

One possible solution would be to amend the Internal Revenue Code to create a Small Business Uniform Retirement Account as a voluntary alternative for employers with 500 or fewer employees, which they could choose instead of (1) simplified employee pensions (SEPs); (2) salary reduction SEPs; (3) SIMPLE IRA plans; (4) SIMPLE 401(k) plans; (5) Keogh plans; (6) regular 401(k)s; (7) profit-sharing plans; (8) money purchase pension plans; and (9) employee stock ownership plans. The Small Business Uniform Retirement Account would have (1) check-the-box eligibility; (2) uniform employee eligibility; (3) automatic enrollment of employees with an option to opt out; (4) no nondiscrimination, coverage, or key-employee rules; (5) contribution levels to be chosen by the employee; (6) maintenance through a financial institution; and (7) availability to employees and self-employed persons, including partners and LLC members. - Permit cash-method accounting for firms with up to $10 million in gross receipts. Cash-method accounting is simpler, reduces compliance costs, and aids small businesses’ cash flow.[26]

- S corporation liberalization. Congress should permit S corporations to have more than 100 shareholders, more than one class of stock, and nonresident alien shareholders (subject to 30 percent withholding on dividends). Raising the limit of 100 shareholders is particularly important if S corporations are to have practical access to the crowdfunding or Regulation A+ provisions in the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act,[27] which would allow companies to raise small amounts from a large number of investors using the Internet once the Securities and Exchange Commission promulgates rules implementing the JOBS Act crowdfunding provisions and the new Regulation A+ rules are effective. It is preferable for the S corporation rules to emulate the partnership rules so that there would be no shareholder limit, although S corporation status would not be available to publicly traded corporations.[28]

- Repeal the Obamacare health insurance tax. Obamacare imposes an excise tax on health insurance premiums that effectively targets small businesses because larger firms self-insure (with or without stop-loss insurance) and therefore do not pay health insurance premiums. It is roughly equivalent to a 2.5 percent tax. This tax should be repealed.[29]

- Increase the incentive stock option (ISO) cap limitation from $100,000 to $250,000. Section 422(d) of the Internal Revenue Code limits ISOs to $100,000 in aggregate stock value (not gain). This limits the utility of ISOs as a means to attract talent.

- Full deductibility for health insurance purchased by the self-employed. Currently, health insurance costs incurred by the self-employed, including partners and LLC members, are deductible for income tax purposes, but not for purposes of the 15.3 percent self-employment tax. This creates a special tax burden on the self-employed not borne by anyone else in the economy. There should be parity between the self-employed and those who are employed. Internal Revenue Code §162(l)(4) should be repealed.

- Clarify rules governing the extent to which distributions from pass-through entities are subject to payroll taxes. The issue of how to delineate between labor income (subject to payroll taxes) and capital income (not subject to payroll taxes) has existed since at least the 1980s. and it has never been adequately resolved. The current legal ambiguity causes uncertainty and leads to audits. Reasonable, clear, and uniform rules governing “reasonable compensation” and investment income should be adopted for partnerships, S corporations, and C corporations.

- Clarify employee independent contractor rules. This issue has existed since at least the 1970s and has never been adequately resolved. The current legal ambiguity creates uncertainty and leads to audits. This is of even greater importance given the employer mandate in Obamacare. The rules promulgated under Obamacare incorporated the tax definition of who is or is not an employee. Provisions should be adopted allowing the employer to choose in ambiguous cases, subject to 1099 reporting and moderate backup withholding, whether a payee is an employee or a contractor.[30]

Phase 3: Finishing the Job with a Complete Cash-Flow Tax

In the final phase of business reform, Congress should finish the job by fully instituting a cash-flow system for all businesses. The policies laid out below assume Congress has already applied the same rate to C corporations and pass-through businesses.

Specifically, Congress should:

- Lower the business tax rate to 20 percent. The U.S. tax rate of approximately 39 percent includes an average state corporate income tax of 4 percent. Ideally, the overall U.S. business tax rate should be lower than the OECD average rate of 25 percent. To achieve a combined federal and state corporate income tax rate lower than the OECD average rate, Congress should reduce the federal rate to 20 percent.[31]

- Establish a territorial tax system. A lower tax rate on foreign income would be an improvement, but to fix completely the problems caused by the worldwide tax system, Congress needs to scrap it altogether and replace it with a territorial system. It can do that by establishing a dividend-exemption regime similar to Chairman Camp’s tax reform proposal in 2014.[32] A territorial system would free U.S. businesses to invest more abroad by making investments profitable that are unprofitable under the current worldwide system. The increase in foreign investment would increase domestic investment by businesses in support of their foreign operations and their efficiency and competitiveness as well. This would create jobs and raise wages for U.S. workers.[33]

However, a territorial system requires a robust set of policies to prevent improper base erosion and profit shifting.[34] Without such policies, U.S. businesses could shift income earned in the U.S. to countries with lower tax rates. Shifting income that should be taxable in the U.S. abroad would improperly narrow the tax base and force tax rates to be higher on domestic-only businesses and families. Higher tax rates hurt growth and are therefore antithetical to the core purpose of engaging in tax reform.

Under deferral, foreign corporations owned by U.S. corporations can earn income overseas and much of it is not taxed until it is sent back to the U.S.[35] Some have estimated that U.S. corporations have earned an estimated $2.1 trillion overseas that has not been repatriated and subject to U.S. tax.[36] As part of moving toward a territorial tax system, this income should be deemed to be repatriated and taxed at a reasonable rate. The businesses that earned this foreign source income expected to pay tax on this money eventually and to exempt it from tax entirely would constitute an unwarranted windfall gain. However, because current law allows for deferral and because of the time value of money, taxing this income under a deemed repatriation at the full corporate rate would be equally unfair. The new revenue from this deemed repatriation can make a substantial contribution to funding other positive aspects of business tax reform. - Provide full and immediate expensing. In the modern, technology-focused economy, the rate of capital cost recovery is an afterthought for some. However, it still matters a great deal since investment in capital formation remains immensely important for economic growth. In spite of improvements that 50 percent expensing would represent, the capital cost recovery period under the tax code would still be too lengthy. Consequently, the tax code would still raise the cost of capital and deter U.S. companies from investing. This would slow job creation and wage growth. To fully establish a cash-flow system, Congress would need to allow businesses to deduct the entire cost of capital purchases at the time businesses make them.

Once Congress takes these three important steps, combined with improvements in earlier phases, it will have established a cash-flow tax and modernized the business tax system so that it is once again competitive with other developed countries. The American people will greatly benefit when Congress fully implements these changes because economic growth, job creation, and wages will grow sharply.

Conclusion

The U.S. economy badly needs business tax reform. The U.S. has the least competitive business tax system in the industrialized world, and this is holding back the economy, productivity improvement, and the wages of the American people. Congress and President Obama should seek to fix this by instituting business tax reform in three phases.

In Phase 1, Congress should take a first step toward a cash-flow system by:

- Lowering marginal business tax rates,

- Applying that rate to C corporations and pass-through businesses,

- Lowering taxes on the foreign income of U.S. businesses, and

- Making 50 percent expensing permanent.

In Phase 2, Congress should:

- Improve the efficiency of the tax code by eliminating unjustified tax preferences, and

- Substantially simplify and clarify the tax law in many areas that are long overdue for improvement.

In Phase 3, Congress should finish moving the business tax system to a cash-flow tax by:

- Lowering the rate to 20 percent or less,

- Enacting a territorial regime for the foreign income of U.S. businesses, and

- Allowing businesses full expensing for their capital investments.

These long overdue policy improvements will likely reduce tax revenue even if Congress eliminates business tax preferences. Yet the archaic business tax system is such a drag on the economy that the tax cut would be a small price to pay for the benefits that the American people would enjoy.

—Curtis S. Dubay is Research Fellow in Tax and Economic Policy and David R. Burton is Senior Fellow in Economic Policy in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.