On December 14, the Federal Communications Commission voted 3-2 to repeal the Commission’s 2015 order imposing net neutrality rules. The 2015 order had reclassified broadband internet from an information service to a telecommunications service, allowing the FCC to regulate internet service providers as common carriers. The 2015 order had included rules against discriminating against content through blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization. We asked a number of experts what the repeal will mean for internet users.

Robert McDowell

Throughout my career, I have supported federal policies that promote an open and freedom-enhancing internet. These policies were built upon long-standing and bipartisan public policy that insulated the internet ecosphere from unnecessary regulation. Since being privatized in the 1990s, the internet proliferated explosively precisely because of light-touch government policies. In short, it blossomed beautifully in the absence of ex ante economic regulation, such as Title II of the Communications Act.

Prospering in the absence of heavy-handed Depression-era regulations designed for the Ma Bell monopoly, internet markets, consumers, and entrepreneurs alike were protected by nimble and strong antitrust and competition laws that traditionally have been enforced by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. The Federal Communications Commission radically departed from that long-standing bipartisan consensus in 2015 when it classified, for the first time, broadband internet access services under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, a law designed for phones that were held in two hands.

Reclassification of broadband services as “telecommunications services” under Title II has caused market and regulatory uncertainty, consumer confusion, and a slowing of investment. U.S. markets have witnessed a significant reduction in broadband investment in the two years since the FCC adopted its Title II Order. The effect is most evident in the hyper-competitive wireless market. For example, CTIA reports that wireless capital expenditures fell 17.8 percent from 2015 to 2016 alone, from $32.1 billion in 2015 to $26.4 billion in 2016.

The FCC’s action also stripped the FTC of its jurisdiction over broadband markets by triggering the “common carrier exemption.” By reversing its anomalous 2015 Title II Order, the FFC restored the FTC’s jurisdiction. The FCC’s decision also allows state attorneys general to continue enforcing similar state consumer protection laws to protect their constituents. In other words, the FCC repeal of the 2015 Title II Order makes clear that time-tested antitrust and competition laws continue to apply, thus giving market players in the internet ecosphere the certainty and freedom to invest, innovate, and prosper.

U.S. markets have witnessed a significant reduction in broadband investment in the two years since the FCC adopted itsTitle II Order.

We all share the same goals of making sure that every American has access to open and freedom-enhancing networks—and that the United States continues to lead the world in the race to 5G. To achieve those goals, we must rely upon America’s nimble and strong antitrust, competition, and consumer protection laws to address any market failure or consumer harm.

The FCC is wise to return to the bipartisan, light-touch regulatory structure that started during the Clinton administration and fostered the dynamic internet economy for almost 30 years.

Mr. McDowell is a fellow at the Hudson Institute and a partner at Cooley LLP. From 2009 to 2013 he served as a Federal Communications Commissioner.

The Federal Communications Commission’s vote repealed its net neutrality rules like Rome destroyed Carthage. No trace was left. It was “the end of the internet as we know it,” blared identical headlines on CNN.com and MSNBC.com. “[P]rices will go up, variety and diversity will go down and the largest, best-capitalized Internet companies will gain a significant advantage over upstart competitors” reported Rolling Stone. Cutting through the niceties, another commentary announced that FCC Chairman Ajit Pai had “killed” the internet.

Scary stuff. But all total hogwash. The regulations that were repealed on December 14 were in force a total of 30 months, from June 2015 to December 2017. That’s barely enough time for a regulator to write up a Federal Register notice. It is not even as long as it takes for the inevitable litigation to be completed (in fact, the rules were still being considered by the Supreme Court when they were repealed).

The end of this two-year experiment in government-controlled internet service is unlikely to be noticed by users. Websites will not go dark; prices won’t rise; the internet will not die; the world will not end. As FCC Commissioner Michael O’Rielly stated: “[F]or those of you out there who are fearful of what tomorrow may bring, please take a deep breath. This decision will not break the internet.”

In the long-run, however, there will be a difference. The much maligned internet service providers—led by AT&T and Verizon—who have funded the infrastructure of the web as it grew beyond all imagining, and who until last year were the leading capital investors in the U.S. economy, will continue investing in the internet after all. The slow-downs and the congestion with which users would have had to contend will not materialize. Innovation will continue as well—both for ISPs (such as T-Mobile, whose pro-consumer zero-rating program that provided free content to subscribers was on the FCC chopping block) and for small startups looking for new ways to challenge the big internet players such as Google and Amazon.

One prediction is likely to come true, however. The internet as we know it will change. It will grow and evolve and disrupt as it has so beneficially for the past 30 years. The internet is always reinventing itself, improving the world in the process. Let’s hope that regulators in Washington never again adopt a policy that could jeopardize that.

Mr. Gattuso is a senior research fellow in regulatory policy at The Heritage Foundation.

Berin Szóka

Rolling back the Obama Federal Communication Commission’s orders means both less and more than you might think.

Remember: the FCC didn’t have any enforceable regulations on the books until 2015. Yet, somehow the internet flourished. So why wasn’t there rampant blocking, throttling, and censorship by broadband companies?

credit: GURUXOOX/GETTY IMAGES

Some claim it was the looming threat of FCC action over a decade the agency spent grasping for a legal basis to do something about net neutrality. But even under the most sweeping possible authority, the FCC couldn’t have stopped the abuses activists fear.

In 2015, the FCC reclassified broadband providers as common carriers (essentially, utilities) subject to Title II of the 1934 Communications Act—the framework designed for Ma Bell, and the railroads before that. In 2017, the D.C. Circuit upheld this reclassification, with one glaring caveat: “[T]he rule does not apply to an ISP [Internet Service Provider] holding itself out as providing something other than a neutral, indiscriminate pathway—i.e., an ISP making sufficiently clear to potential customers that it provides a filtered service.” So as long as they were upfront about it, broadband providers could have engaged in “editorial intervention, such as throttling of certain applications chosen by the ISP, or filtering of content into fast (and slow) lanes based on the ISP’s commercial interests”—and Title II simply wouldn’t have applied.

The Democratic-appointed judges who wrote that decision went on: “No party disputes that an ISP could [opt out of Title II] if it wished, and no ISP has suggested an interest in doing so in this court. That may be for an understandable reason: a broadband provider representing that it will filter its customers’ access to web content based on its own priorities might have serious concerns about its ability to attract subscribers.” In the most meaningful sense of the term, market forces demanded net neutrality.

In the most meaningful sense of the term, market forces demanded net neutrality.

Of course, the normal antitrust and competition laws applied to check abuse, too—at least until 2015. See, Title II reclassification deprived the Federal Trade Commission of jurisdiction: the FTC can regulate (nearly) everything but common carriers. Moving broadband back to Title I (only public safety FCC regulations, not economic ones) restores the FTC’s jurisdiction. A Ninth Circuit panel had suggested it might not be so simple, but the full appeals court vacated that decision.

The FTC’s baseline deception authority will work essentially the same way Title II would have: “requir[ing] ISPs to act in accordance with their customers’ legitimate expectations,” as the court put it. That’ll be even easier because the FCC will keep mandating ISP transparency (under uncontroversial legal authority). The FTC, the nation’s premiere consumer watchdog, will also have broader authority to punish practices that harm consumers or competition—joined by state attorneys general (of both parties) and the Department of Justice. If anything, net neutrality is on firmer ground now than ever.

credit: LUKE MACGREGOR/REUTERS/NEWSCOM

But it won’t last. The FCC will be sued again, and will win again, for the same reasons they’ve won the last two rounds: Chevron deference to agencies. The next Democratic FCC chairman will reclaim broad powers over the internet. There are only two ways to stop this ping-pong match: The core of net neutrality isn’t controversial and could be codified in statute in exchange for blocking future FCC power grabs. Congressional Republicans proposed doing just that three years ago. Democrats never engaged, and probably won’t now, since this is an electoral winner for them. Or, the Supreme Court could rule that imposing broad internet regulation is a “major question” requiring a clear statement from Congress.

Mr. Szóka is president of TechFreedom, a non-partisan think tank supported by companies on both sides of the net neutrality debate.

Randolph J. May

The Federal Communications Commission’s decision to repeal the net neutrality mandates imposed on internet service providers by the Obama administration FCC is a welcome development for internet users. The Obama-era internet regulations were adopted in 2015 without any evidence of an existing market failure or consumer harm. When regulations address hypothetical instead of real problems, investment and innovation almost always are discouraged to the detriment of consumers.

In this instance, the likelihood of ill-effects was heightened because the FCC imposed public utility-like mandates on internet service providers—the same “command and control” regulatory regime that applied to railroads in the 19th century and Ma Bell in the 20th century. The problem, of course, is that unlike those railroads and Ma Bell, internet providers operate in a largely competitive marketplace environment that is technologically dynamic.

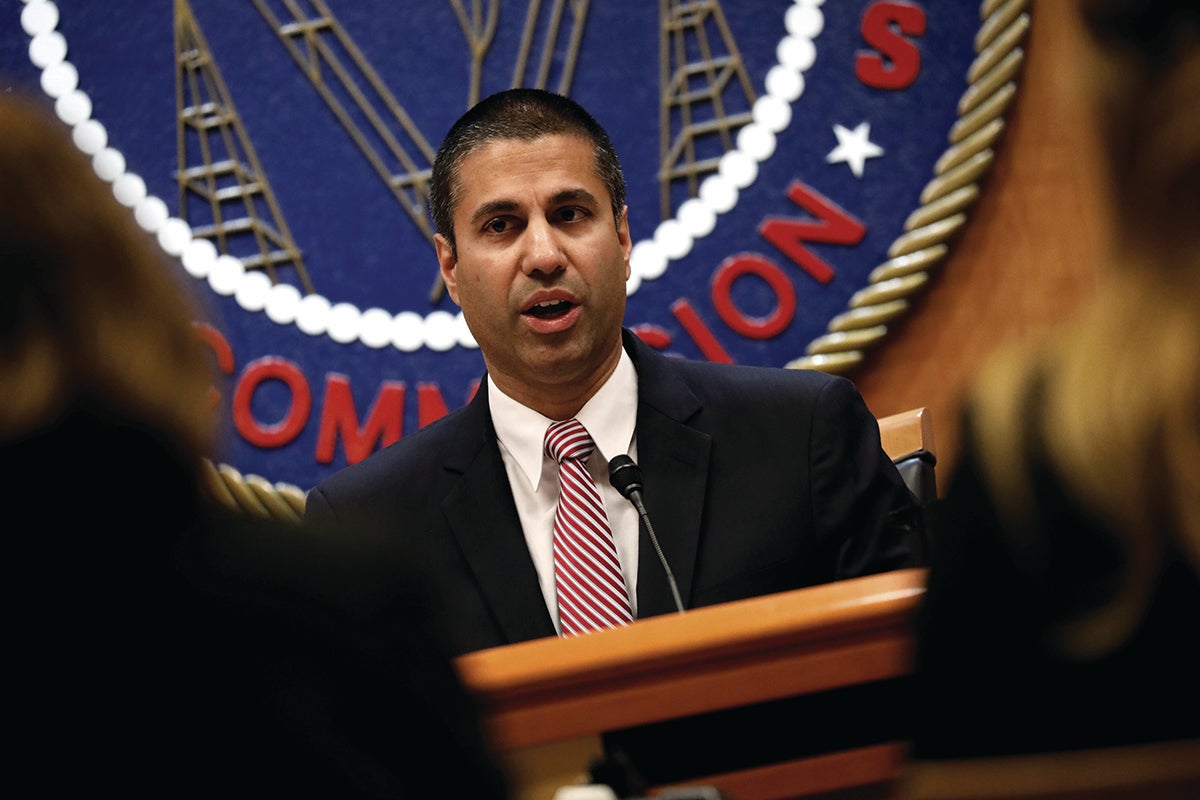

CHAIRMAN AJIT PAI speaks ahead of the vote on the repeal of so-called net neutrality rules at the Federal Communications Commission, December 14, 2017. (credit: AARON P. BERNSTEIN/REUTERS/NEWSCOM)

There is no dispute that between 1996 and 2015 ISPs invested $1.5 trillion in building out advanced broadband networks at a time when broadband deployment and adoption were expanding rapidly. But there is persuasive evidence that since 2015, when the FCC adopted the current public utility regime, ISP investment has declined. For example, a May 2017 Free State Foundation study estimated that capital expenditures for the 16 largest ISPs declined $5.6 billion since 2015 and other studies show similar reductions.

In June 2017, Cisco released its latest internet traffic forecast, projecting that global IP traffic will increase three-fold over the next five years and will have increased 127-fold from 2005 to 2021. As demand for broadband bandwidth continues to increase exponentially, especially with the explosion of the consumption of online video, it is obvious that any decline in investment in advanced broadband networks, or even a decline in the rate of investment, bodes ill for internet users.

When regulations address hypothetical instead of real problems, investment and innovation almost always are discouraged to the detriment of consumers.

Also boding ill is the potential suppression of innovation resulting from public utility-like regulation of ISPs. We have a real-world example. After the FCC adopted its 2015 order, then-Chairman Tom Wheeler ordered an investigation of popular “free data” programs offered by the ISPs. These programs, popularized first by upstart T-Mobile in its effort to challenge its larger wireless competitors, allow subscribers to access certain websites without incurring data usage charges. Shortly after President Trump appointed Ajit Pai the agency’s new chairman, he terminated the investigations, which many ISPs had reported chilled their plans for other innovative offerings.

So, repealing the existing internet regulations is likely to benefit consumers by spurring innovation and investment. But it’s fair to ask whether, after the repeal, consumers will still be protected.

The answer is yes. Under a return to a light-touch regulatory regime, the FCC will continue to enforce transparency rules that require internet service providers to publicly disclose their practices relating to blocking, throttling, or prioritizing internet traffic. If ISPs fail to make the required disclosures, the FCC can impose sanctions. And if they fail to adhere to their representations, the Federal Trade Commission, pursuant to its authority to prevent unfair or deceptive practices, can impose sanctions. The FTC has the experience, expertise, and institutional capabilities to carry out its consumer protection responsibilities effectively.

After the FCC adopted its 2015 order, then-Chairman Tom Wheeler ordered an investigation of popular “free data” programs offered by the ISPs that allow subscribers to access certain websites without incurring data usage charges.

Moreover, the antitrust authorities will be on guard as well to rectify any anticompetitive abuses to the extent that there is a showing of the wrongful exercise of market power. And state officials will retain their traditional powers to enforce state consumer protection laws.

So, internet users remain protected after the repeal of net neutrality regulations. And, importantly, they are likely affirmatively to benefit from the removal of regulations that discouraged investment and innovation.

Mr. May is president of the Free State Foundation, a nonpartisan free market-oriented think.

Larry Downes

The short answer is nothing.

What the Federal Communications Commission has done is to return internet governance to where it was from 1996 until 2015, with the Federal Communications Commission applying a light-touch oversight to broadband, in accord with congressional intent. The Federal Trade Commission will return as principle enforcer, able once again to police ISPs under general laws of antitrust and consumer protection.

ACTIVISTS PROTEST in support of net neutrality outside a Verizon store in Lower Manhattan in New York on December 7, 2017. (Credit: RICHARD B. LEVINE/NEWSCOM)

That long-standing bipartisan approach—the overwhelmingly positive results of which speak for themselves—was undone by an ill-considered and possibly illegal decision, by the FCC in 2015 to reclassify ISPs as public utilities, exposing them to the full range of federal and state regulations designed to manage the former Bell monopoly in the 1930s. At the same time, the FTC’s authority was immediately cut off under a law that prohibits them from regulating public utilities.

Reclassification, the agency said at the time, was needed to give the commission legal cover to enforce specific network management restrictions against blocking, throttling, or otherwise discriminating against internet traffic for anti-competitive reasons. Federal courts had twice rejected these rules as outside the agency’s congressional mandate. Yet in previous efforts to pass them, the FCC acknowledged that broadband ISPs weren’t actually violating the so-called open internet principles. The rules, the agency said repeatedly, were mere “prophylactics.”

Instead, increased competition and the growing leverage of dominant internet content providers was doing a near-perfect job of deterring practices that might harm the open internet—and doing so without the uncertainty, cost, delay, and regulatory capture inherent in the FCC’s radical alternative.

The rules provided no benefit, but imposed considerable cost. The “prophylactic” rules—or more accurately the public utility reclassification—resulted in dramatic decreases in infrastructure investment, just at the time when new mobile networks and U.S. global competitiveness needed more, not fewer, incentives. The 2015 order ended a run of Wall Street exuberance that saw over $1.5 trillion in private spending during the light-touch regulation era.

Net neutrality advocates’ long-term and openly-stated goal all along has been to transform the internet into a nationalized network or quasi- governmental utility.

With the public utility order wisely retired, internet users will in fact have considerably more protections than they did prior to 2015. That’s because the FCC is leaving in place and enhancing one of the five so-called net neutrality rules—one that will require ISPs to disclose their network management practices, with those promises explicitly enforceable by both the FCC and the FTC.

Advocacy groups have been flagellating in recent weeks about the end of the internet, democracy, free speech, and whatever else they think might enrage consumers about the FCC’s common-sense decision to return to a regulatory model that had worked brilliantly. The scare tactics make clear that they were never interested in enforceable net neutrality rules. Their long-term and openly-stated goal all along has been to transform the internet into a nationalized network or quasi-governmental utility. They gambled in 2015 that the next FCC chairman would share their vision. They lost.

Thank goodness they did. A quick look at the state of U.S. electricity, gas, and water utilities, mass transit systems, crumbling roads, bridges, and other national infrastructure should make clear the obvious danger of wheels put well in motion by the FCC in 2015. The agency’s swift reverse course gives consumers hope for continued innovation—even if they won’t realize it until the rhetoric quiets down.

Mr. Downes is Project Director at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy and the co-author of Big Bang Disruption: Strategy in the Age of Devastating Innovation (Portfolio).