—Daniel N. Robinson, 20161

Life

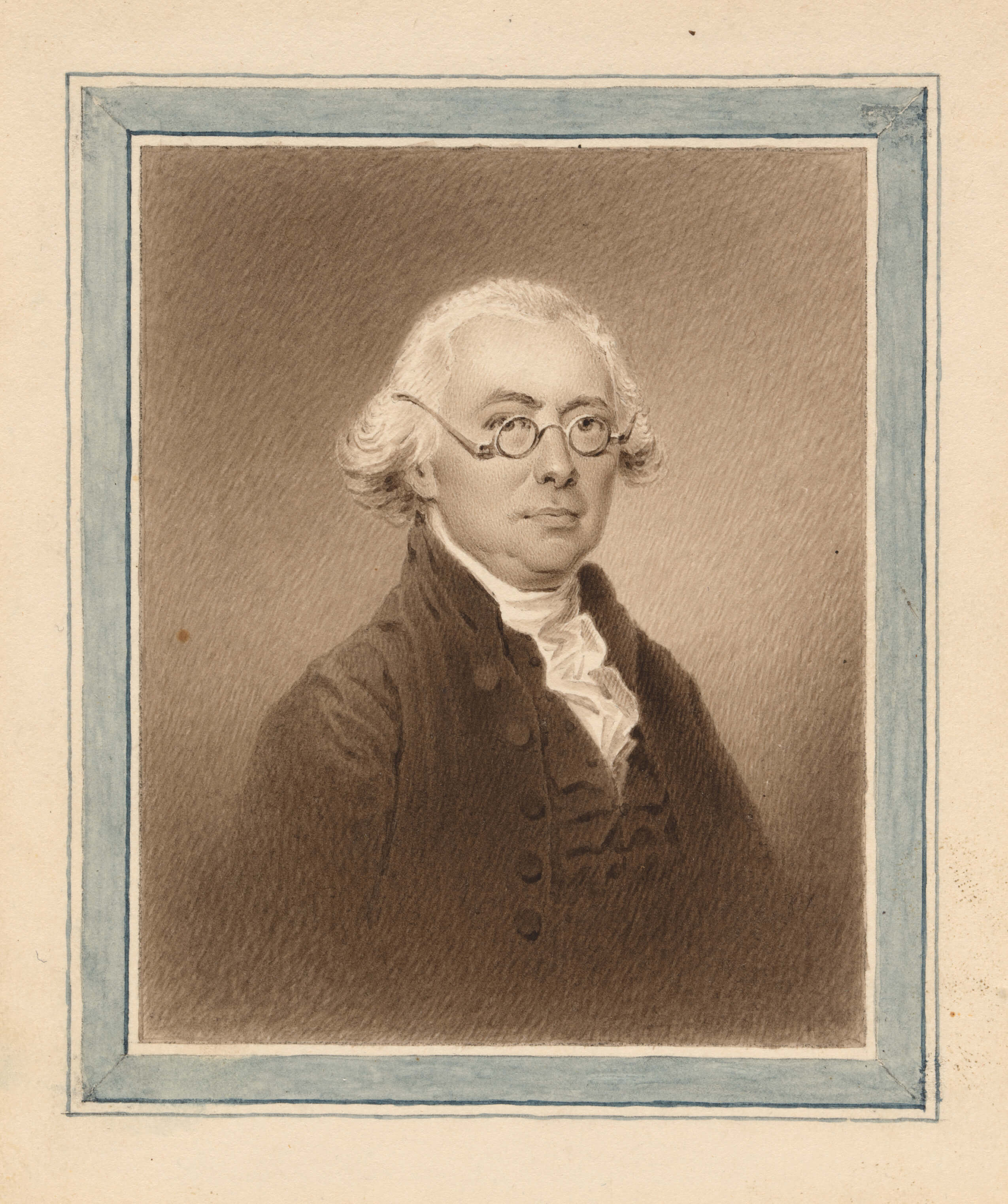

James Wilson was born on September 14, 1742, in Carskerdo, Scotland. He was the firstborn son of farmers William Wilson and Alison Landall Wilson. After finishing his studies, Wilson emigrated from Scotland to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1765. He began as a teacher at the College of Philadelphia and then entered his career in law, first as an apprentice to attorney John Dickinson and later setting up his own law practice. In 1771, he married Rachel Bird, daughter of a wealthy landowner; they had six children together. Rachel died in 1786, and seven years later, Wilson married Hannah Gray. While Wilson spent the last decade of his life as a Supreme Court Justice, he was entangled in financial difficulties caused by the debts he accumulated from his land speculations. He died of malaria on August 21, 1798, at 55 years of age.

Education

Wilson received an early education at a local grammar school before winning a scholarship to the University of St. Andrews at age 15. He also briefly attended the Universities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. He received an honorary master’s degree from the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) and then studied law with John Dickinson.

Religion

Episcopalian

Political Affiliation

Federalist

Highlights and Accomplishments

1774: Author, “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament”

1775–1777: Delegate to Second Continental Congress

1782–1783: Delegate to Confederation Congress

1785–1787: Delegate to Confederation Congress

1787: Delegate to Constitutional Convention

Undated: Signer, Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution

1787: Delegate to Pennsylvania Ratification Convention

1789–1798: Associate Justice, first U.S. Supreme Court

1804: Works and Lectures on Law (published posthumously)

James Wilson had a critical hand in making the America that the world would come to know, yet he prefigured the coming American story because he was not native born. He was born in Carskerdo, Scotland, in 1742, the son of a farmer, and managed to get a classical education at the Culpar grammar school. From there he would spring to a scholarship at the University of St. Andrews in 1757. He had the good fortune to be in the academy in Scotland during the golden years of what would later be called the Scottish Enlightenment. The intellectual air would be vibrant with the works of Francis Hutcheson, Thomas Reid, and Dugald Stuart, whose works would gain a wide and discerning readership in America. The remarkable essays of Reid, so accessibly clear, penetrating, and witty, would come to thread through Wilson’s elegant lectures on law.

With his learning in hand, something in him—some animating ambition and verve—impelled him to America. He landed in America at the time of the Stamp Act crisis when he was 23 years old. His credentials were plausible enough to gain him a position as a tutor in Latin and lecturer in English literature at the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania), but he quickly left those posts to take up the study of law under John Dickinson, who would himself become a leading figure in the cause of independence. Only two years after his arrival in Philadelphia, Wilson was admitted to the bar, and a year later, in 1768, he was already setting himself up in a practice in Reading, Pennsylvania. His industry and ambition at full throttle, he borrowed money and began his first investments in land, an interest that would carry him to his most troubled times.

In 1770, Wilson moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, broadening his practice. He soon married Rachel Bird, the daughter of a wealthy landowner in Berks County; as Kermit Hall has observed, the union “joined her family’s considerable wealth with the young lawyer’s voracious appetite for speculation in land.”2 Six children would come from that 15-year marriage, which lasted until Rachel’s death in 1786. Several years later, he would marry again to a much younger woman who would survive him.

Everything about Wilson seemed to mark drive and energy, and soon he was plunged into the revolutionary politics exploding so near him. In 1774, he became the chairman of the Committee of Correspondence in Carlisle, and the next year he was elected to the provincial Assembly, which in turn led him to the Continental Congress. In the building arguments moving toward independence in 1776, Wilson was initially restrained by the legislature of Pennsylvania from voting for independence, but when the legislature gave its representatives leave to vote their consciences, Wilson switched his vote and ultimately signed the Declaration of Independence—one of only six people to sign both the Declaration and the Constitution.

The very thrust of the Revolution brought forth the sense of nationhood taking hold, and Wilson was moving toward a stronger government at the national level. That conviction would move him forcefully past the Articles of Confederation. He would be a confirmed and ever more affirming nationalist when he joined the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787. On the path to the Convention, he had already begun to put in place the keys to the argument, as shown most notably in the tract he had written in 1774, Considerations on the Nature and Extent of Legislative Authority of the British Parliament.

Through the years, the key line “all men are created equal” has been credited to Thomas Jefferson in his writing of the Declaration of Independence—albeit prefigured in the Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason, declaring that “all men are by nature equally free and independent.” Lincoln took the idea expressed in that line of the Declaration of Independence as the first principle, the defining principle, of the new American regime. It turns out that before Jefferson and Mason put pen to paper, it was Wilson who had written the line containing this idea two years earlier in a passage that filled out quite precisely the meaning that the Declaration sought to convey:

All men are, by nature, equal and free: no one has a right to any authority over another without his consent: all lawful government is founded on the consent of those who are subject to it: such consent was given with a view to ensure and to increase the happiness of the governed above what they could enjoy in an independent and unconnected state of nature.3

However, its more precise argument, the case for natural equality, hinged on the inequalities in nature. As the argument ran, no man was by nature the ruler of other men in the way that God was by nature the ruler of men and men were by nature the rulers of horses and dogs. In contrast to the claims of kings to the standing of sovereign or superiors, Wilson allowed in his lectures on law that the rule of a superior would be eminently fitting for “Him who is supreme.” But if some men were in the position of ruling over others, that state of affairs could not have arisen from nature. It had to arise, as the saying went, by agreement or consent.

And so flowed the conclusion in the Declaration of Independence that the only legitimate governments over human beings “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed.” That condition was attached in turn to the very purpose for which that government was made. It all began in the Declaration with that Creator who endowed us “with certain unalienable Rights,” and “that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men.” Wilson would make the point even more sharply in his lectures on law: We did not bring forth this new government and Constitution in order “to acquire new rights by a human establishment,” but rather “to acquire a new security for the possession or the recovery of those rights” that flowed to us “by the immediate gift, or by the unerring law, of our…Creator.”4

The great Sir William Blackstone had famously written that when men leave the “state of nature” and enter civil society, they surrender those unlimited rights that they had in the state of nature, including the “liberty to do mischief.” They exchange those unlimited rights for a more limited set of rights under “civil society”—call them “civil rights”—which are rendered more secure by the advent of a government with the power to enforce them. To which Wilson replied: When did we ever have a “liberty to do mischief to any one”?5 Or, as Lincoln would later put it, there is no “right to do wrong.”6 Those laws that restrain people from raping and murdering had never restrained them from anything they had a rightful liberty to do. Thus, when the question was raised, “What rights do we give up when entering under this new Constitution?,” the answer tendered by the Federalists at the time was “None.” As Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 84, “Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing.” We did not enter into this new government for the purpose of giving up our natural rights. Therefore, what sense did it make to speak of a codicil, a set of amendments to the Constitution, marking off the rights we had not given up—as though on entering into this Constitution we had surrendered the bulk of our natural rights?7

What needs to be understood about Wilson and Hamilton and the Federalists of that period is that the securing of natural rights was the defining telos or purpose of this new government. Therefore, it was the purpose that attached to every branch of the government—to every member of the executive and legislative branches as well as the judiciary.

On a Right to Revolution Contained in the Law

In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, Blackstone said that it was a solecism to contend that a principle of revolution may be incorporated in the laws. Laws, after all, work to settle things; revolutionary acts of disobedience dramatically unsettle them. In a gesture of striking opposition, Wilson adhered to the teaching in the Declaration and insisted that “a revolution principle certainly is, and certainly should be taught as a principle of the constitution of the United States, and of every State in the Union.”8 America would contain in its constituting character a principle of revolution because in America, there was the keen sense that there could indeed be an unjust law, a law enacted with the trappings of fine procedure but wanting in the substance of justice. It might be wanting, that is, in a serious moral justification for a measure that would remove personal choice and impose an obligation bearing on everyone within the reach of the law. But that state of affairs could exist only because America would begin with a vivid sense of natural rights and natural law: Statesmen in America had access to a body of moral truths quite independent of the positive law, and by those standards, the positive law may be judged for its rightness or wrongness.

All of this described the principles that would mark a popular government with a constitutional order, a regime under the rule of law. These principles were there before Wilson and his colleagues set about the task of deliberating over the structure of a constitution. The task of framing a constitution was to create a structure of governance that was faithful to the defining principles of this political order. The first constitution brought forth the Articles of Confederation, a league of states rather than a real government that could act directly on individuals and enforce its own laws. With discriminatory tariffs and taxes marking the borders of the states, this arrangement would not bring together the people of one nation, but instead would spur on the centrifugal tendencies, driving the states and their people further apart. By the time the delegates were settling in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, there was a sharp sense of what brought them there.

The Constitutional Convention: Setting to Work

The move to the Constitutional Convention was sparked by the leading figures in Virginia, and no one was more leading than George Washington. Governor Edmund Randolph thought it fitting that at the opening of the meetings on May 29, the Virginians would have something serious to offer as an account of why they were there. What were the defects in the Articles of Confederation that brought forth the urgent need for this gathering—and where would the corrections be found? The crisis was marked by a supposed national government that could not summon the authority or power to protect the country from foreign invasion any more than it could restrain quarrels among the states or put down an insurrection. The federal government had no power to extract from the states the funds needed to sustain its operations, to ward off encroachments from the states, or make its own measures paramount to those of the states. Randolph would put forth a plan (largely the handiwork of Virginian James Madison) for a national legislature of two chambers and an independent judicial branch with judges holding their position “during good behavior.” There would be an executive, elected by and therefore dependent on the legislature and ineligible for a second term of office. This would not be the plan that finally emerged from this Convention, and in one of the leading ironies, Randolph himself held back from signing the document that emerged.

But past the strains and balancing, Randolph had put forth the most decisive plan that would separate this new Constitution from the Articles of Confederation. The basis of the remedy for the current discontents would be found in the “republican principle,” and it would be a real government—one that could act directly on individual persons in enforcing its measures while drawing its authority from the “consent of the governed.” It would not be a congress of states where the “citizens” were the states.9

With remarkable celerity, that anchoring pin in the Virginia Plan—that “a national Governt. ought to be established consisting of a supreme Legislative Executive & Judiciary”—was accepted the very next day, May 30.10 Exactly how those branches would be constituted would offer thorny subjects to be explored in the months to follow.

Wilson would sign on at once to a key feature in the plan: the establishment of a real government that could act directly on individuals in enforcing its measures and command the revenue to sustain itself. He was a nationalist at every turn: “We must remember the language with [which] we began the Revolution, it was this, Virginia is no more, Massachusetts is no more—we are one in name, let us be one in Truth & Fact….”11 As recounted in Madison’s notes:

He could not persuade himself that the State Govts. & sovereignties were so much the idols of the people, nor a Natl. Govt. so obnoxious to them, as some supposed. Why [should] a Natl. Govt. be unpopular? Has it less dignity? [W]ill each Citizen enjoy under it less liberty or protection? Will a Citizen of Delaware be degraded by becoming a Citizen of the United States? Where do the people look at present for relief from the evils of which they complain?… It is from the Natl. Councils that relief is expected. For these reasons he did not fear, that the people would not follow us into a national Govt. and it will be a further recommendation of Mr. R[andolph]’s plan that it is to be submitted to them and not to the Legislatures, for ratification.12

The Virginia Plan provided for an executive composed of three persons—Randolph thought that a single executive would become the “fetus of monarchy.”13 However, all of the 13 states had single executives, and Wilson was convinced that concentrating authority in a single figure would sharpen responsibility. For Wilson, that was a step toward a mode of voting through electors, yet whether it was the executive or the legislature, Wilson was for “raising the federal pyramid to a considerable altitude, and for that reason wished to give it as broad a basis as possible. No government could long subsist without the confidence of the people. In a republican Government this confidence was peculiarly essential.”14 He favored popular election for both houses of the legislature and the executive. In regard to the executive, he would come to make his peace with the Electoral College, but he was ever more nationalist and ever more of the conviction that it was the views of the people that are to be represented faithfully, in both chambers of the legislature. Madison recorded his remarks:

Mr. Wilson…wished for vigor in the Govt. but he wished that vigorous authority to flow immediately from the legitimate source of all authority. The Govt. ought to possess not only 1st. the force but 2ndly. the mind or sense of the people at large. The Legislature ought to be the most exact transcript of the whole Society. Representation is made necessary only because it is impossible for the people to act collectively.15

The Virginia Plan engaged the members in conversations for two weeks; then on June 15, William Paterson came forward with a strong alternative, which would be known as the New Jersey Plan or Small State Plan. This plan would offer a dramatic conversion of a Confederation into a real government; it would preserve the main structures of the Articles while trying to strengthen the powers of the federal government. It was a baby step but nonetheless a step.16

Central to Paterson’s plan was equality of voting in the upper chamber. When the small states dug in on this issue, they pushed certain members of the large states to the point of exasperation. Randolph of Virginia spoke of adjourning the Convention, but he quickly backed away from the notion that he was willing to adjourn the Convention sine die—which is to say bring the Convention and the very prospect of a new Constitution to an end—and he and members of the large states reluctantly accepted the “Great Compromise.”

As political scientist John Londregan observed years later, the small states had “cleaned the clock” of the large states. In preserving an equality of voting by states in the upper chamber and having Senators elected by the legislators of the states, the Convention had preserved the federal structure of the Articles of Confederation as a lingering power of restraint. Wilson swallowed hard but managed to put a better face on the outcome: “In the Articles of Confederation, the people are unknown, but in this plan they are represented; and in one of the branches of the legislature, they are represented immediately by persons of their own choice.”17

“The Most Difficult of All on Which We Have Had to Decide”

On the question of the executive, there were many moves back and forth with nearly as many changes of mind by the delegates. Late in the game, on September 4, Wilson said that “[t]his subject has greatly divided the House, and will also divide people out of doors. It is in truth the most difficult of all on which we have had to decide.”18

Wilson declared on June 1 with regard to the executive that “at least…in theory he was for an election by the people; Experience, particularly in N. York & Massts, shewed that an election of the first magistrate by the people at large, was both a convenient & successful mode.” By the next day, he was already moving toward a mediated version of election by the people. He offered a countering motion on the election of the executive: “That the States be divided into districts: that the persons qualified to vote in each district for members of the first branch of the national Legislature elect members for their respective districts to be electors of the Executive magistracy.” The advantage for Wilson was that this was a mode of election “without the intervention of the States.”19 The motion was voted down decisively, with only two states in favor, but for Wilson, that was a step toward a mode of voting through electors.

On September 4, the Committee of Eleven had brought forth its proposal that “[e]ach State shall appoint in such manner as its Legislature may direct, a number of electors equal to the whole number of Senators and members of the House of Representatives, to which the State may be entitled in the Legislature.”20 Wilson “thought the plan on the whole a valuable improvement on the former. It gets rid of one great evil, that of cabal & corruption.”21 If the vote were held in one assembly in a leading city, there would be schemes abounding to control the outcome; with the centers of decision scattered to 13 separate places, the burdens of manipulation were made fittingly harder.

The Culminating Touch

One of Wilson’s most enduring effects on the Constitutional Convention came as a culminating touch, likely to go unnoticed. It came through his work on the Committee of Detail before the text was put into the hands of Gouverneur Morris, joined by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, in the Committee of Style. The Preamble initially settled on for the Constitution read:

We the People of the States of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina and Georgia, do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of ourselves and of our Posterity.22

This passage marked a critical divide among the Framers about the nature of the polity coming into being and the sources of its authority. Wilson’s argument, as it would be Lincoln’s later, was that the Declaration of Independence marked the beginning of a national people.23 The question, then, as historian Jonathan Gienapp has rephrased it, was whether “the government presiding over that nation was the creation not of the people of the separate states but of the sovereign people of the United States.”24 Wilson’s understanding would find a resonating accord with Gouverneur Morris, and when the final draft came from the Committee of Style, the Preamble now read, in the words that have become so familiar today:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

And so, when foreign governments would extend diplomatic recognition to this new Republic, they would not send emissaries to Boston, Hartford, or other major cities within the states. They would send ambassadors accredited to the seat of the one national government.

Years later, in a famous January 1833 Senate speech, Daniel Webster would appeal to the Preamble during the crisis over nullification when states were claiming their rights to declare certain acts of Congress unconstitutional. Webster rejected the notion that the Constitution had come about through a “social compact” among the states. He also rejected the view that the people of the United States made a contract with the government over the rights they would keep or waive; the government of the United States does not stand as an equal contracting party in relation to the people. Rather, the government is an agent in relation to its principal or sovereign. The government began not with a contract, but with the sovereign people “ordaining” and establishing this Constitution for its governance.25 According to Webster, just as the states had not “acceded” to the Constitution, by the same logic the states could claim no right to secede from the Constitution. This logic accords with Wilson’s conviction that the fundamental and only source of constitutional authority resides in the sovereign people.

Tracing the Deep Premises of the Constitutional Order

Wilson’s enduring legacy can be found in the writing he would bring forth when he was appointed to the first Supreme Court and in the elegant lectures he would compose and deliver at the College of Philadelphia when he was honored with a chair there. Much has been made of the attendance for that first lecture on December 15, 1790. President Washington and Vice President Adams were in attendance, as were many members of the Senate and the House. It may be hard to find the proper metric of things, but that singular audience brought out for this inaugural lecture surely provides a telling measure of the place in which that figure on the podium stood in the circle of the American Founding.

Wilson would compose 58 lectures, about half of which he managed to deliver. In these lectures, Wilson accomplished far more than any of his successors in setting forth a body of jurisprudence that would bear the imprint of his name. It was said that Wilson wished to produce a body of work that would displace in America the importance of Blackstone’s Commentaries. At the level of sales, that dream was not realized, but in executing the work, he more than fulfilled his intention. For what he accomplished, more than any other justice or commentator on the law, was to put in place a distinctly American jurisprudence, rooted in the moral grounds of natural law and natural right.

This teaching began right away in one of the earliest cases to be printed in the Supreme Court’s U.S. Reports, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793).26 Chisholm involved the question of whether a state could rightly be sued by a vendor when the state did not fulfill its contract. In resisting the suit, the state asserted a claim of “sovereign immunity,” a right not to be brought into court by a private party.

The term “sovereignty” had been widely used in regard to the supreme ruling power of a state, but Wilson insisted that “[t]o the Constitution of the United States the term SOVEREIGN, is totally unknown.” Wilson explained that:

[S]overeignty is derived from a feudal source; and like many other parts of that system so degrading to man, still retains its influence over our sentiments and conduct, though the cause, by which that influence was produced, never extended to the American States.… In process of time the feudal system was extended over France, and almost all the other nations of Europe: And every Kingdom became, in fact, a large fief.27

That new appellation was planted with a “double operation.” The king, or sovereign, would become the “fountain of justice.” Sovereignty invested “him with jurisdiction over others, [while] it excluded all others from jurisdiction over him.”28 Hence the notion of sovereign immunity. But it marked at once that the law in America would be based on a foundation entirely different from the foundation of the law in England. The law in England proceeded from the “principle…that all human law must be prescribed by a superior.” That superior could not be challenged in court, for he was the source of all law. In America, wrote Wilson, “another principle, very different in its nature and operations, forms, in my judgment, the basis of sound and genuine jurisprudence; laws derived from the pure source of equality and justice must be founded on the CONSENT of those, whose obedience they require. The sovereign, when traced to his source, must be found in the man.”29 He would be found, that is, in the human person tendering his consent to the terms on which he is to be governed.

When seen through this lens, there is a dramatic difference between the old world and the new in the understanding of “that terrain or political order, that is ruled.” In America, the polity is not the possession of a king or sovereign as such. Rather, what is meant by a “state” or polity is “a complete body of free persons united together for their common benefit, to enjoy peaceably what is their own, and to do justice to others.”30 It is a collective of natural persons and yet in its “body politic” is also “an artificial person” that endures through the ages with interests, rights, and obligations:

[I]t has its rights: And it has its obligations. It may acquire property distinct from that of its members: It may incur debts to be discharged out of the public stock, not out of the private fortunes of individuals. It may be bound by contracts; and for damages arising from the breach of those contracts. In all our contemplations, however, concerning this feigned and artificial person, we should never forget, that, in truth and nature, those, who think and speak, and act, are men.31

And because they are men, they may be tasked in their associational form with the same responsibilities that arise for other men. If the question were raised, then, as to whether Georgia as a state, as an association of persons, may be held responsible for its debts, the answer is that it is bound on the same ground as any of its members—real persons—may be bound. “The only reason,” said Wilson, “why a free man is bound by human laws, is, that he binds himself. Upon the same principles, upon which he becomes bound by the laws, he becomes amenable to the Courts of Justice, which are formed and authorised by those laws. If one free man, an original sovereign, may do all this; why may not an aggregate of free men, a collection of original sovereigns, do this likewise?”32

It was critical to Wilson that the American people had not surrendered the bulk of their natural rights upon entering into this new Constitution. That was the key to their aversion to a bill of rights with the lingering implication that the people had indeed waived their fuller, natural rights in exchange for a guarantee of that select list of rights set down in the first eight amendments. The core of the matter came back to that critical mistake made by Blackstone about the source of those rights. Blackstone had mentioned in his Commentaries that “the right[s] of personal security” and “personal liberty” were not “natural rights,” but the “civil liberties” of Englishmen. Blackstone admitted, said Wilson, that these rights “are founded on nature and reason,” but he also insisted that “their establishment, as excellent as it is, is still human.” Blackstone traced these liberties, as other conservatives in our own day have, to the Magna Carta and subsequent laws of England. Natural rights were considered merely as “civil privileges provided by society, in lieu of the natural liberties given up by individuals.” However:

If this view be a just view of things, then the consequence, undeniable and unavoidable, is, that, under civil government, the right of individuals to their private property, to their personal liberty, to their health, to their reputation, and to their life, flow from a human establishment [i.e., the positive law], and can be traced to no higher source. The connexion between man and his natural rights is intercepted by the institution of civil society.33

The point not to be missed here is that Blackstone’s position—finding the ground of our rights traceable back to the Magna Carta and the following expansion of English liberties—is precisely the understanding favored by many conservatives today. In Wilson’s judgment, that was a mark of heresy: It marked a curious failure to take seriously the notion of truths grounded in nature or of a government that found its telos—its governing purpose—in securing those rights that were there before the positive law.

The state, said Wilson, was “made for man.” More than that, it was the finest work of man. But man, “fearfully and wonderfully made, is the workmanship of his all perfect Creator….”34 In the circles of the educated today it is far easier to assume that our civil institutions are the sources of our rights rather than that Creator whom the Founders credited with endowing us with rights. Years later, this connection was made in another, precise way by Pope Leo XIII in his 1881 encyclical on liberty. The pope said that it made no sense to impute property rights to animals, for cows and horses cannot impart a moral purpose to inanimate matter or property. It makes sense to speak of rights only for creatures of reason—beings who can reason about the ground of their own well-being and the well-being of others, moral agents who understand that they may not claim a “right to do wrong” even in the name of their freedom. Only creatures of this kind understand that for every liberty there is a version of license, that any liberty can be used for rightful or wrongful ends.

All of this came, as Thomas Reid and Leo XIII understood, from the Creator who gave us these creatures of reason who alone could understand the laws of reason. Those creatures and the “laws of reason” were part of the same Creation that gave us “the Laws of Nature,” the laws of physics and mathematics. For Wilson and other Founders such as John Adams, all of this made sense. It was atheism that seemed to make no sense or to offer any scheme of moral coherence.

Americans were, of course, divided on contending revelations over the Creator who endowed us with rights, brought the Hebrews out of Egypt, and begot a Son who died on the cross, but there were many things they generally shared in reasoning about God in the manner of natural theology. They reasoned their way to an Uncaused Cause of the Universe, and they knew that God was not material in nature, for matter was ever subject to decomposition.

On the connection between natural law and natural theology, James Wilson leaned on the teachings of Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, especially his treatise on The Principles of Natural Law and Politic Law (1742). In that engaging work, Burlamaqui managed to settle in the most delicate way that enduring question about the source of the law or the grounds of obedience: Even if the law commands what is right and forbids what is wrong, what commands our obligation to respect that judgment? The most familiar answer was that the law emanates from a Lawgiver; we are obliged to obey the One who commands. The other answer was that the law is grounded in the laws of reason, in propositions that we are obliged to respect because they have the sovereign attribute of being true. As Burlamaqui put it, the authority of the Lawgiver may provide the external incentive to obey the law, but that external incentive is given a further, internal support when the law is in accord with the laws of reason. The compelling force of the reason behind the law may augment our confidence that the law must indeed be in accord with the intentions of the Lawgiver.35

Taking Things to the Root

Whether it is natural theology or political philosophy, everything runs back to the anchoring axioms of our reasoning. As Wilson understood, everything begins with the things that we must be able to grasp in the first instance as a matter of common sense, as a self-evident truth, just as we grasp that “every effect has a cause.” René Descartes famously said, “I think, therefore I am,” but Wilson wondered how he could know that thoughts were his if he really wasn’t sure that he himself was there. On the anchoring truth of one’s existence, Wilson said, “I can find no previous truth more certain or more luminous, from which this can derive either evidence or illustration.” This is one of those things that just must be taken as certain, for “some such antecedent truth is necessarily the first link in a chain of proof. For proof is nothing else than the deduction of truths less known or less believed, from others that are more known or better believed.”36

That was the prime lesson he sought to teach in the very opening of his first decision in Chisholm v. Georgia. He noted that we were at the very beginning of the law under this new Constitution, so there were no real precedents upon which to draw. He thought it would be necessary, in approaching these first cases in our law, to return to the “general principles of jurisprudence.” Even before that, he thought it was necessary to remind ourselves of the principles of mind, or the grounds on which we can claim reliably to know anything. He appealed to that “original and profound writer” on “the philosophy of mind,” the great Scot philosopher Thomas Reid, and his “excellent enquiry into…the principles of common sense,” standing against that “sceptical and illiberal philosophy, which under bold, but false, pretentions is liberality, prevailed in many parts of Europe before he wrote….”37 For Wilson, the first step of jurisprudence in America was to detach itself from moral relativism in any of its forms.

What drew Wilson to Reid were his teachings on the precepts of “common sense” that precede all “theories.” They are the things so naturally evident that the ordinary person not only knows them; he takes them as things necessary to know just in getting on with the ordinary business of life: Before the average man would banter, say, with the philosopher David Hume over the meaning of “causation,” he knows his own active powers to cause his own acts to happen.

Wilson pressed persistently to those anchoring grounds of the law, for the various “theories” on offer could not be judged until they were taken back to the root axioms that give them any plausible claim to truth. As he claimed, “first principles are in themselves apparent; that to make nothing self[-]evident, is to take away all possibility of knowing any thing; that without first principles [supplying the ground of our reason], there can be neither reason nor reasoning.…”38

This is to say that Wilson would stand against any of the theories of our own day, claiming our credence about the terms of principle on which we should live. Put another way, Wilson stands for moral realism all the way down, set against the novelties or theories of our own time. He would set himself against any theory that detaches itself from the anchoring ground on which we could judge its truth, for such anchoring truths mark the beginning of everything we would ever claim to know.

Selected Primary Writings

“Of the Natural Rights of Individuals”39

What was the primary and the principal object in the institution of government? Was it—I speak of the primary and principal object—was it to acquire new rights by a human establishment? Or was it, by a human establishment, to acquire a new security for the possession or the recovery of those rights, to the enjoyment or acquisition of which we were previously entitled by the immediate gift, or by the unerring law, of our all-wise and all-beneficent Creator?

The latter, I presume, was the case: and yet we are told, that, in order to acquire the latter, we must surrender the former; in other words, in order to acquire the security, we must surrender the great objects to be secured.…

But all the other rights of men are in question here. For liberty is frequently used to denote all the absolute rights of men. “The absolute rights of every Englishman,” says Sir William Blackstone, “are, in a political and extensive sense, usually called their liberties.”

And must we surrender to government the whole of those absolute rights? But we are to surrender them only—in trust:—another brat of dishonest parentage is now attempted to be imposed upon us: but for what purpose? Has government provided for us a superintending court of equity to compel a faithful performance of the trust? If it had; why should we part with the legal title to our rights?

After all; what is the mighty boon, which is to allure us into this surrender? We are to surrender all that we may secure “some:” and this “some,” both as to its quantity and its certainty, is to depend on the pleasure of that power, to which the surrender is made. Is this a bargain to be proposed to those, who are both intelligent and free? No. Freemen, who know and love their rights, will not exchange their armour of pure and massy gold, for one of a baser and lighter metal, however finely it may be blazoned with tinsel: but they will not refuse to make an exchange upon terms, which are honest and honourable—terms, which may be advantageous to all, and injurious to none.

The opinion has been very general, that, in order to obtain the blessings of a good government, a sacrifice must be made of a part of our natural liberty. I am much inclined to believe, that, upon examination, this opinion will prove to be fallacious. It will, I think, be found, that wise and good government—I speak, at present, of no other—instead of contracting, enlarges as well as secures the exercise of the natural liberty of man: and what I say of his natural liberty, I mean to extend, and wish to be understood, through all this argument, as extended, to all his other natural rights.

This investigation will open to our prospect, from a new and striking point of view, the very close and interesting connexion, which subsists between the law of nature and municipal law.…

“The law,” says Sir William Blackstone, “which restrains a man from doing mischief to his fellow citizens, though it diminishes the natural, increases the civil liberty of mankind.” Is it a part of natural liberty to do mischief to any one?…

In a state of natural liberty, every one is allowed to act according to his own inclination, provided he transgress not those limits, which are assigned to him by the law of nature: in a state of civil liberty, he is allowed to act according to his inclination, provided he transgress not those limits, which are assigned to him by the municipal law. True it is, that, by the municipal law, some things may be prohibited, which are not prohibited by the law of nature: but equally true it is, that, under a government which is wise and good, every citizen will gain more liberty than he can lose by these prohibitions. He will gain more by the limitation of other men’s freedom, than he can lose by the diminution of his own. He will gain more by the enlarged and undisturbed exercise of his natural liberty in innumerable instances, than he can lose by the restriction of it in a few.

Upon the whole, therefore, man’s natural liberty, instead of being abridged, may be increased and secured in a government, which is good and wise. As it is with regard to his natural liberty, so it is with regard to his other natural rights.…

Government, in my humble opinion, should be formed to secure and to enlarge the exercise of the natural rights of its members; and every government, which has not this in view, as its principal object, is not a government of the legitimate kind.

“Of Man, as an Individual”40

“Know thou thyself,” is an inscription peculiarly proper for the porch of the temple of science. The knowledge of human nature is of all human knowledge the most curious and the most important. To it all the other sciences have a relation; and though from it they may seem to diverge and ramify very widely, yet by one passage or another they still return.…

…The statesman and the judge, in pursuit of the noblest ends, have the same dignified object before them. An accurate and distinct knowledge of his nature and powers, will undoubtedly diffuse much light and splendour over the science of law. In truth, law can never attain either the extent or the elevation of science, unless it be raised upon the science of man.…

…Frequent and laborious have been the attempts of philosophers to investigate the manner, in which things external are perceived by the mind. Let us imitate them, neither in their fruitless searches to discover what cannot be known; nor in framing hypotheses which will not bear the test of reason, or of intuition; nor in rejecting self[-]evident truths, which, though they cannot be proved by reasoning, are known by a species of evidence superiour to any that reasoning can produce.

Many philosophers allege that our mind does not perceive external objects themselves; that it perceives only ideas of them; and that those ideas are actually in the mind. When it has been intimated to them, that, if this be the case; if we perceive not external objects themselves, but only ideas; the necessary consequence must be, that we cannot be certain that any thing, except those ideas, exists; the consequence has been admitted in its fullest force. Nay, it has been made the foundation of another theory, in which it has been asserted, that men and other animals, the sun, moon, and stars, every thing which we think we see, and hear, and feel around us, have no real existence; that what we dignify with such appellations, and what we suppose to be so permanent and substantial, are nothing more than “the baseless fabrick of a vision”—are nothing more than ideas perceived in the mind. The theory has been carried to a degree still more extravagant than this; and the existence of mind has been denied, as well as the existence of body. We shall have occasion to examine these castles, which have not even air to support them. Suffice it, at present, to observe, that the existence of the objects of our external senses, in the way and manner in which we perceive that existence, is a branch of intuitive knowledge, and a matter of absolute certainty; that the constitution of our nature determines us to believe in our senses; and that a contrary determination would finally lead to the total subversion of all human knowledge.…

Our external senses are not indeed the most exalted of our powers; but they are powers of real use and importance; and, to powers of a more dignified nature, they are most serviceable and necessary instruments. It has been the endeavour of some philosophers to degrade them below that rank, in which they ought to be placed. They have been represented as powers, by which we receive sensations only of external objects…. The perception of external objects is a principal link of that mysterious chain, which connects the material with the intellectual world. But this … is not the whole of the functions discharged by the senses: they judge, as well as inform: they are not confined to the task of conveying impressions; they are exalted to the office of deciding concerning the nature and the evidence of the impressions, which they convey.…

…Our senses ought to be deemed, as they really are, and as they are intended to be, the useful and pleasing ministers of our higher powers. Let it be remembered, however, that, of the pleasures of sense, temperance and prudence are the necessary and inseparable guides and guardians; detached from whom, those pleasures lose themselves in another nature and in other names: they become vices and pains.

As the external senses convey to us information of what passes without us; we have an internal sense, which gives us information of what passes within us. To this we appropriate the name of consciousness. It is an immediate conception of the operations of our own minds, joined with the belief of the existence of those operations. In exerting consciousness, the mind, so far as we know, makes no use of any bodily organ. This operation seems to be purely intellectual. Consciousness takes knowledge of every thing that passes within the mind. What we perceive, what we remember, what we imagine, what we reason, what we judge, what we believe, what we approve, what we hope, all our other operations, while they are present, are objects of this.

This, like many other operations of the mind, is simple, peculiar, inaccessible equally to definition and analysis. For its existence every one must make his appeal to himself. Are you conscious that you remember, or that you think? We have already seen, that the existence of the objects of sense is one great branch of intuitive knowledge: of the same kind of knowledge, the existence of the objects of consciousness is another branch, more extensive and important still. When a man feels pain, he is certain of the existence of pain; when he is conscious that he thinks, he is certain of the existence of thought. If I am asked to prove that consciousness is a faithful and not a fallacious sense; all the answer which I can give is—I feel, but I cannot prove; I can find no previous truth more certain or more luminous, from which this can derive either evidence or illustration. But some such antecedent truth is necessarily the first link in a chain of proof. For proof is nothing else than the deduction of truths less known or less believed, from others that are more known or better believed. “What can we reason, but from what we know?” The immediate and irresistible conviction, which I have of the real existence of those things, of whose existence I am conscious, is a conviction produced by intuition, not by reason. He who doubted, or pretended to doubt, concerning every other information, deemed himself justified in taking for granted the veracity of that information, which was given to him by his consciousness. He was conscious that he thought; and therefore he was satisfied that he really thought.—“Cogito” was a first principle, which he who pronounced it dangerous and unphilosophical to assume any thing else, judged it safe and wise to assume. And when he had once assumed that he thought, he gravely set to work to prove, that because he thought he existed. His existence was true, but he could not prove it; and all his attempts to prove it have been shown, by a succeeding philosopher, to be inconsistent with the rules of sound and accurate logick. But even this succeeding philosopher, who showed that Des Cartes had not proved his existence, and who, from the principles of his own philosophy could not assume this existence without proof—even this philosopher has assumed the truth of the information given by consciousness. “Mr. Hume, after annihilating body and mind, time and space, action and causation, and even his own mind, acknowledges the reality of the thoughts, sensations, and passions, of which he is conscious.” He has left them—how philosophically I will not pretend to say—to “stand upon their own bottom, stript of a subject, rather than call in question the reality of their existence.” Let us felicitate ourselves, that there is, at least, one principle of common sense, which has never been called in question. It is a first principle, which we are required and determined, by the very constitution of our nature and faculties, to believe. Perhaps we shall find other first principles, which, by the same constitution of our nature and faculties, we are equally required and determined to believe. Such principles are parts of our constitution, no less than the power of thinking: reason can neither make nor destroy them: like a telescope, it may assist, it may extend, but it cannot supply natural vision….

Every free action has two causes, which cooperate in its production. One is moral; the other is physical: the former is the will, which determines the action; the latter is the power, which carries it into execution. A paralytick may will to run: a person able to run, may be unwilling: from the want of will in one, and the want of power in the other, each remains in his place.

Our actions and the determinations of our will are generally accompanied with liberty. The name of liberty we give to that power of the mind, by which it modifies, regulates, suspends, continues, or alters its deliberations and actions. By this faculty, we have some degree of command over ourselves: by this faculty we become capable of conforming to a rule: possessed of this faculty, we are accountable for our conduct.…

Reason is a noble faculty, and when kept within its proper sphere, and applied to its proper uses, exalts human creatures almost to the rank of superiour beings. But she has been much perverted, sometimes to vile, sometimes to insignificant purposes. By some, she has been chained like a slave or a malefactor; by others, she has been launched into depths unknown or forbidden.

Are the dictates of our reason more plain, than the dictates of our common sense? Is there allotted to the former a portion of infallibility, which has been denied to the latter? If reason may mistake; how shall the mistake be rectified? shall it be done by a second process of reasoning, as likely to be mistaken as the first? Are we thus involved, by the constitution of our nature, in a labyrinth, intricate and endless, in which there is no clue to guide, no ray to enlighten us? Is this true philosophy? is this the daughter of light? is this the parent of wisdom and knowledge? No. This is not she. This is a fallen kind, whose rays are merely sufficient to shed a “darkness visible” upon the human powers; and to disturb the security and ease enjoyed by those, who have not become apostates to the pride of science. Such degenerate philosophy let us abandon: let us renounce its instruction: let us embrace the philosophy which dwells with common sense.

This philosophy will teach us, that first principles are in themselves apparent; that to make nothing self-evident, is to take away all possibility of knowing any thing; that without first principles, there can be neither reason nor reasoning; that discursive knowledge requires intuitive maxims as its basis; that if every truth would admit of proof, proof would extend to infinity; that, consequently, all sound reasoning must rest ultimately on the principles of common sense—principles supported by original and intuitive evidence.

In the investigation of this subject, we shall have the pleasure to find, that those philosophers, who have attempted to fan the flames of war between common sense and reason, have acted the part of incendiaries in the commonwealth of science; that the interests of both are the same; that, between them, there never can be ground for real opposition: that, as they are commonly joined together in speech and in writing, they are inseparable also, in their nature.…

…Des Cartes, at the head of modern reformers in philosophy, anxious to avoid the snare, in which Aristotle and the peripateticks had been caught—that of admitting things too rashly as first principles—resolved to doubt of every thing, till it was clearly proved. He would not assume, as a first principle, even his own existence. In what manner he supposed nonexistence could institute, or desire to institute a series of proof to prove existence or any thing else, we are not informed.

He thought he could prove his existence by his famous enthymem—Cogito, ergo sum. I think, therefore, I exist. Though he would not assume the existence of himself as a first principle, he was obliged to assume the existence of his thoughts as a first principle. But is this entitled to any degree of preference? Can one, who doubts whether he exists, be certain that he thinks? And may not one, who, without proof, takes it for granted that he thinks—may not such an one, without the imputation of unphilosophick credulity, take it for granted, likewise without proof, that he exists?

In every just proof, a proposition less evident is inferred from one, which is more evident. How is it more evident that we think, than that we exist? Both are equally evident: one, therefore, ought not to be first assumed, and then used as a proof of the other.

But further; if we attend to the strict rules of proof; the existence of Des Cartes was not legitimately inferred from the existence of his thoughts. If the inference is legitimate; it must become legitimate by establishing this proposition—that thought cannot exist without a thinking being. But did Des Cartes, or has any of his followers proved this proposition? They have not proved it: they cannot prove it. Mr. Hume has denied it; and has triumphantly challenged the world to establish it by proof. The basis of his philosophy is, as we have already seen—“that a train of successive perceptions constitute the mind.”

Let me not here be misunderstood. When I say, that the existence of a thinking principle, called the mind, has not been and cannot be proved; I am far from saying, that it is not true, that such a thinking principle exists. I know—I feel—it to be true; but I know it not from proof: I know it from what is greatly superiour to proof: I see it by the shining light of intuition.

Recommended Readings

- William Ewald, “James Wilson and the American Founding,” in “Symposium: The Life and Career of Justice James Wilson,” Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Winter 2019), pp. 1–21, www.law.georgetown.edu/public-policy-journal/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2019/06/17-1-Ewald.pdf.

- William Ewald and Lorianne Updike Toler, “Early Drafts of the U.S. Constitution,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 135, No. 3 (July 2011), https://doi.org/10.5215/pennmaghistbio.135.3.0227.

- John Mikhail, “The Necessary and Proper Clauses,” Georgetown Law Journal, Vol. 102, No. 4 (April 2014), pp. 1045–1132, https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1083437.

- Kermit L. Hall, Introduction, in The Collected Works of James Wilson, 2 Vols., ed. Hall and Mark David Hall (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2007), https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/garrison-collected-works-of-james-wilson-2-vols.

- Daniel N. Robinson, “Moral Science at the Founding: Ruling Passions,” lecture, Amherst College, October 31, 2003, https://www.amherst.edu/media/view/42591/original/Robinson-Moral.htm.

Notes

[1] Daniel N. Robinson, “Is There Anything ‘Essentially’ Human? James Wilson’s Critique of Locke,” lecture for the James Wilson Institute, March 16, 2016, posted by the Wheatley Institution, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65pLuKMXFQg&ab_channel=WheatleyInstitute (accessed April 26, 2025).

[2] Kermit L. Hall, Introduction to the Collected Works of James Wilson, ed. Kermit L. Hall and Mark David Hall (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2007), Vol. I, p. xvii, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/2072/Wilson_4140.01_LFeBk.pdf (accessed April 26, 2025). Hereinafter Collected Works.

[3] James Wilson, “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament, 1774,” in Collected Works, Vol. I, pp. 4–5.

[4] James Wilson, “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals,” in Collected Works, Vol. II, pp. 1053–1054, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/2074/Wilson_4140.02_LFeBk.pdf (accessed April 26, 2025),

[5] Ibid., p. 1055.

[6] “The Lincoln–Douglas Debates 7th Debate Part II,” October 15, 1858, Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-lincoln-douglas-debates-7th-debate-part-ii/ (accessed April 26, 2025).

[7] For a more detailed statement of the argument here, see Hadley Arkes, “On the Dangers of a Bill of Rights: Restating the Federalist Argument,” Chapter 4 in Beyond the Constitution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), pp. 58–80.

[8] James Wilson, “Introductory Lecture: Of the Study of the Law in the United States,” in Collected Works, Vol. I, p. 443.

[9] For Randolph’s presentation of the Virginia Plan, see The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, ed. Max Farrand (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 1911), Vol. I, pp. 18–23, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1057/0544-01_Bk.pdf (accessed April 26, 2025). Hereinafter Records.

[10] Ibid., p. 35.

[11] Ibid., p. 172.

[12] Ibid., p. 253. Italics in original.

[13] Ibid., p. 66.

[14] Ibid., p. 49.

[15] Ibid., pp. 132–133. Emphasis in original.

[16] Ibid., pp. 243–244.

[17] The Debates in the Several States on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, 2nd ed., ed. Jonathan Elliot (Washington: Printed for the Editor, 1836), Vol. II, pp. 439–440, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1906/1314.02_Bk.pdf (accessed April 26, 2025). Hereinafter Elliot’s Debates.

[18] Records, Vol. II, p. 501.

[19] Records, Vol. I, p. 80

[20] Records, Vol. II, p. 497.

[21] Ibid., p. 501.

[22] Ibid., p. 565.

[23] See Wilson, “Considerations on the Bank of North America” before the Constitution was framed: “Though the United States in Congress assembled derive from the particular States no power, jurisdiction or right, which is not expressly delegated by the confederation, it does not thence follow, that the United States in Congress have no other powers, jurisdiction or rights, than those delegated by the particular States…. [¶] The act of independence was made before the articles of confederation.… [¶] The confederation was not intended to weaken or abridge the powers and rights, to which the United States were previously entitled. It was not intended to transfer any of those powers or rights to the particular States, or any of them. If, therefore, the power now in question was vested in the United States before the confederation; it continues vested in them still. The confederation clothed the United States with many, though, perhaps, not with sufficient powers: But of none did it disrobe them. [¶] It is no new position, that rights may be vested in a political body, which did not previously reside in any or in all the members of that body. They may be derived solely from the union of those members. ‘The case,’ says the celebrated Burlamaqui, is here very near the same as in that of several voices collected together, which, by their union, produce a harmony, that was not to be found separately in each.” Collected Works, Vol. I, pp. 65–67. Footnotes omitted. But see also John Mikhail, “The Necessary and Proper Clauses,” Georgetown Law Review, Vol. 102, No. 4 (April 2014), pp. 1045–1132, https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1083437 (accessed April 26, 2025).

[24] Jonathan Gienapp, Against Constitutional Originalism: A Historical Critique (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2024), p. 128.

[25] Daniel Webster, Speech in the Senate on Nullification, January 1833, The Constitution Not a Compact Between Sovereign States, in Select Speeches of Daniel Webster, 1817–1845, in Project Gutenberg online: “The first question then is, what does [the Constitution] say of itself? What does it report to be? Does it style itself a league, confederacy, or compact between sovereign States?… A constitution is the fundamental law of the state; and this is expressly declared to be the supreme law. It is as if the people had said, “We prescribe this fundamental law,” or “this supreme law,” for they do say that they establish this constitution, and that it shall be the supreme law. They say that they ordain and establish it. Now, sir, what is the common application of these words? We do not speak of ordaining leagues and compacts.” Daniel Webster, “The Constitution Not a Compact Between Sovereign States,” in Select Speeches of Daniel Webster 1817–1845 (Boston: D.C. Heath, 1893), pp. 272–273, https://dn790003.ca.archive.org/0/items/selectspeechesof00websuoft/selectspeechesof00websuoft.pdf (accessed April 26, 2025).

[26] Chisholm v Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793).

[27] James Wilson, Opinion in Chisholm v. State of Ga., in Collected Works, Vol. I, pp. 352 and 356.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., p. 357. Emphasis in original.

[30] Ibid., p. 354.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Wilson, “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals,” in Collected Works, Vol. II, p. 1057.

[34] Wilson, Opinion in Chisholm v. State of Ga., in Collected Works, Vol. I, p. 353.

[35] See “General Rules of Conduct Prescribed by Reason. Of the Nature and First Foundations of Obligation,” Chapter VI in Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, The Principles of Natural and Politic Law, trans. Thomas Nugent, ed. Peter Korkman (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2006), Vol. I, pp. 79–80, and “Of the Foundation of Sovereignty, or the Right of Commanding,” Chapter IX, in ibid., pp. 92–103, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1717/1347_LFeBk.pdf (accessed April 26, 2025)

[36] James Wilson, “Of Man, as an Individual,” in Collected Works, Vol. I, p. 594.

[37] Wilson, Opinion in Chisholm v. State of Ga., in ibid, p. 352.

[38] Wilson, “Of Man, as an Individual,” in Collected Works, Vol. I, p. 603.

[39] Wilson, “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals,” in Collected Works, Vol. II, pp. 1053–1056, 1061.

[40] Wilson, “Of Man, as an Individual,” in Collected Works, Vol. I, pp. 585, 591–595, 601–604, 616–617. Footnotes omitted.