—City Gazette and Daily Advertiser, Charleston, South Carolina, March 4, 1808

Life

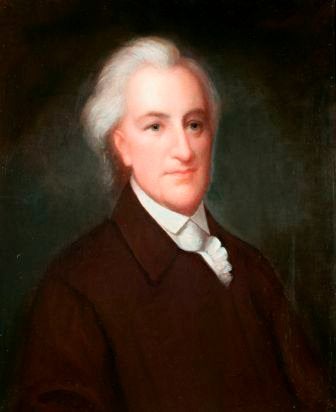

Dickinson was born November 13, 1732, in Talbot County, Maryland, to Samuel Dickinson and Mary Cadwalader Dickinson. He had one full brother, Philemon, and two half-siblings, Henry and Elizabeth. At the age of 38 on July 19, 1770, he married Mary (Polly) Norris, daughter of Isaac Norris, longtime speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly. They had five children: Sally Norris (1771–1855); Mary (1774–1775); John (1778); an unnamed son (1779); and Maria (1783–1860). Dickinson died on February 14, 1808, at his home in Wilmington, Delaware. He is buried in Wilmington Friends Burial Ground.

Education

Dickinson studied under private tutors at home until age 18; read law with former king’s attorney John Moland and passed the bar in Philadelphia (1750–1753); and studied law at the Middle Temple of London’s Inns of Court (1754–1757).

Religion

Unaffiliated; leaned Quaker

Political Affiliation

Republican

Highlights and Accomplishments

1759–1761: Member, Three Lower Counties (Delaware) Assembly

1762–1765: Member, Pennsylvania Assembly

1765: Delegate from Pennsylvania to Stamp Act Congress

1765: Declaration of Rights from Stamp Act Congress

1765: Petition to the King from Stamp Act Congress

1768: Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies

1770, 1774–1776: Member, Pennsylvania Assembly

1774: Delegate from Pennsylvania to First Continental Congress

1774: First Petition to the King

1774: To the Inhabitants of the Colonies

1774: Bill of Rights [and] List of Grievances

1774: Letter to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec

1775–1776: Colonel, First Philadelphia Battalion of Associators

1775–1776: Delegate from Pennsylvania to Second Continental Congress

1775: Second Petition to the King (Olive Branch Petition)

1775: Declaration on the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms

1776: Draft of the Articles of Confederation

1776: Draft of Plan of Treaties

1777: Private, Delaware Militia

1779: Delegate from Delaware to Second Continental Congress

1781–1782: President of Delaware

1782–1785: President, Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania

1786: Chairman, Annapolis Convention

1787: Delegate from Delaware to Constitutional Convention

1788: Letters of Fabius (on ratification of the Constitution)

1791–1792: President, Delaware Constitutional Convention

Despite his present-day relative obscurity, before America declared independence from Great Britain, no American was better known and none was more critical to the cause of resistance and preparation than John Dickinson. Afterward, few were as central to the creation of the new nation. Beginning in 1765 during the Stamp Act crisis and into the era of the early Republic, Dickinson wrote more for the American cause than any other figure, becoming America’s first celebrity and the internationally recognized leader of the response to British measures. His leadership united the colonies and instructed Americans about their rights and how to defend them. As independence looked likely, he restrained separatist impulses among the colonies and worked to build institutions so that a revolution could succeed.

After independence, Dickinson likewise held more public offices at all levels than any other Founder, from the executive office of two states to serving as a private in a state militia. Throughout his life as a lawyer, statesman, and private person, he championed rights not only for the American people as a whole, but also for those with the least power, including laborers, African Americans, women, Native Americans, and criminals. His philanthropy in the early Republic was unsurpassed as he used his vast wealth for the establishment of institutions—including schools, libraries, medical societies, churches, and the first prison reform society—that would serve all Americans. In each capacity, Dickinson attempted to realize the ideal he had set for himself as he finished his legal training: Stand for right and justice whatever the personal cost.

The Life of John Dickinson

John Dickinson was born into a wealthy Quaker family on a Maryland tobacco plantation. His father moved the family to Kent County, one of the Three Lower Counties of Pennsylvania (now Delaware), when Dickinson was seven. At the age of 18, he was apprenticed to former king’s attorney John Moland in Philadelphia, after which he received three years of training at the Middle Temple, one of London’s Inns of Court, to become a barrister. As a lawyer, he imagined himself “defending the Innocent & redressing the Injurd,” because this was the “Noblest Aim of Human Abilities & Industry.”1 In London, he became acutely aware and proud of his American identity, believing virtue and industry were its hallmarks.2 After establishing his law practice in Philadelphia, he rose quickly to prominence, taking all manner of work from lucrative prize cases in the Admiralty Court to trespass cases for yeomen to pro bono cases defending accused murderers.

His career in public service began in 1759 when he was elected to the Assembly of the Lower Counties. The next year, he was reelected and chosen as speaker of the House. He was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1762 and reelected frequently through 1776. His first service to America as a whole was as a delegate to the 1765 Stamp Act Congress in New York, where he was the main draftsman of the Declaration of the Stamp Act Congress and its Petition to the King. In his private capacity, he wrote several treatises concerning British measures and how Americans should resist them peacefully. He was among the earliest American advocates of natural rights.

With the passage of the Townshend Acts in 1767, Dickinson published his most famous document, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, which launched him to international celebrity as the spokesman for the American cause. These 12 letters educated Americans about their rights and how British legislation threatened them, instructed them in peaceful resistance, and taught them to see themselves as Americans with an identity distinct from that of their British cousins. Dickinson’s star status was solidified in the summer of 1768 when he published America’s first patriotic song, the “Liberty Song,” containing the line “By uniting We stand, by dividing We fall,” which became the nation’s first motto. Known as “the Pennsylvania Farmer,” Dickinson was toasted across the colonies; poems were written about him; treatises were dedicated to him; and his likeness was represented in copper, wax, and oil. His name was used to advertise goods and services, from American-made clothing to taverns, ships, and stud horses. Leaders in the other colonies, including Samuel Adams in Massachusetts, the Lees of Virginia, and Alexander McDougall in New York, looked to him for guidance.

In 1770, Dickinson married Mary (Polly) Norris from the most prominent Quaker political family in Pennsylvania. She and their two daughters influenced his thinking on religion, politics, and social justice.

When the First Continental Congress met in 1774, lesser-known men such as George Washington, John Adams, and Patrick Henry sought introductions to the Farmer. Although Dickinson was not initially among the delegates, his agenda for reconciliation and peaceful resistance to British measures dominated. He was the primary draftsman of most of the major congressional documents through 1776. In 1775, his influence continued as Congress pursued his dual plan of seeking reconciliation while preparing for war. At this time, he was the de facto commander of the Pennsylvania militia. Dickinson’s power and influence were such that only George Washington’s rivaled them.

In the winter and spring of 1776, after Thomas Paine’s Common Sense opened the public debate over independence and sentiment shifted in favor of revolution, Dickinson’s influence waned. Yet as his colleagues rushed for independence, Dickinson not only restrained them by prohibiting Pennsylvania from voting for it, but also used that precious time to prepare America to be independent. Had he favored separation in June, he would most likely have been assigned to draft the Declaration. Instead, he drafted the model treaty that became the blueprint for American foreign policy and America’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, although the version implemented in 1781 bore little resemblance to his. On July 1, he gave an eloquent speech against the Declaration and then, knowing both that it would pass and that it should be unanimous, intentionally absented himself from the vote. Because he was not a Quaker and believed in defensive war, he soon deployed to the front, leading his militia unit to face the British.

Dickinson’s public service was no less active after independence was declared. Following his enlistment as a private in the Delaware militia in 1777, he served in Congress in 1779 as a delegate from Delaware. A key member, he sat on nearly 25 committees addressing myriad issues, including corruption in the government, nonpayment of taxes by individuals and the states, negotiations with Britain for peace, and reformation of maritime affairs. In 1781, he was elected to the presidency of Delaware, turning it from a failing to a model state. Before his first term was finished, he was elected president of the Executive Council of Pennsylvania, a state that was in no better shape than Delaware. When he stepped down in 1785, he had resolved several crises that could have damaged the state and nation, including the Mutiny of 1783, which evidence suggests was fomented by Congressmen Gouverneur Morris, William Jackson, and Alexander Hamilton.3

Dickinson then wanted to retire and focus on philanthropy. At this point in his life, he was almost indistinguishable from a Quaker. He used plain speech (“thee” and “thou”); dressed and lived plainly and frugally; and believed deeply in Quaker causes, including abolitionism, poor relief, prison reform, and education. But he was called into public service many more times. In 1786, he was chairman of the Annapolis Convention that met to strengthen the Articles of Confederation. He was an important contributor to the 1787 Federal Convention, offering key concepts, proposals, and solutions for the creation of the Constitution, including the basis for the so-called Connecticut Compromise—the idea that there should be equal representation in one house of the legislature and proportional representation in the other.4 The following year, he wrote nine well-received letters under the pen name “Fabius” to encourage ratification of the Constitution. His constitutional work continued as president of the Delaware constitutional convention of 1791–1792 and the Delaware Senate in the spring of 1793.

In his final years, Dickinson and his wife focused on philanthropy, but he did not abstain from politics altogether. As the first party system took shape, Dickinson identified as a Republican and opposed the policies of Washington and Adams. He led a citizens’ group against the 1794 Jay Treaty, supported the democratic agrarian movement, wrote treatises and odes in support of France and the French Revolution, and served as an informal advisor to President Thomas Jefferson. He also continued to write and advocate legislation for Pennsylvania, Delaware, and the United States.

Over the 15 years of his retirement, Americans never ceased to call for Dickinson’s return to elected office. He obliged them only once. In the fall of 1807, in the wake of the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, he agreed to stand for election to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was not chosen, which at 75 years of age was a relief. On his deathbed, he gave a final oration on the dangers of Napoleon to the United States. After his death, the demonstrations of public grief were second only to those for George Washington and on a par with those for Benjamin Franklin.

Dickinson’s Character

John Dickinson was described by those who met him as gracious, generous, cheerful, and having a “sweet disposition.”5 He made friends easily among all ranks of people wherever he went. Despite occasional health issues, he worked hard; spoke energetically and eloquently about favorite topics, especially politics and religion; and was considered one of the finest orators of the Revolutionary generation. He was also widely seen as a man of the highest character. As a young man studying in England, he was appalled by the corruption in the British political system and spoke of the need for a reformation of manners (that is, morals). Thirty years later, he spoke of the need for a reformation of manners among the American people, which he tried to effect while president first of Delaware and then of Pennsylvania by issuing proclamations on suppressing vice and immorality. Between these times, he attempted to pass legislation in colonial Pennsylvania to prevent politicians—such as Benjamin Franklin, whom Dickinson may have had in mind—from accepting certain offices that would compromise their integrity.

Virtue and honor were not empty talk for Dickinson. He was principled to a fault, refusing so adamantly and consistently to do anything that violated his conscience that he exasperated those closest to him. Honesty and integrity informed all of his work as a statesman, lawyer, and businessman. “[N]o offers however extravagant,” he proclaimed, “shall tempt Me to undertake the sordid Employment of acquiring Gain by violating my Conscience.”6 Nor would he even agree to marry in a Quaker ceremony, despite the love of his life’s requiring this as a condition of marriage. His conscience dictated a civil ceremony, and she eventually obliged.

If there was a single refrain in Dickinson’s life, it was speaking truth to power regardless of the personal cost to himself, his fortune, or his legacy. Innumerable times over his 40-year career, he stood up to assemblies of his superiors and his peers, to judges and juries, even to the American public to say, Martin Luther–like, that here he stood, and his conscience would allow nothing else. He repeatedly made some version of his July 1, 1776, pronouncement: “Silence would be guilt. I despise its Arts. I detest its Advantages. I must speak, though I should lose my Life, though I should lose the Affections of my Countrymen.”7 He embodied the virtue that the Founding generation believed necessary for the survival of the Republic. Defining what it meant to him, he explained that “[a] Man’s Virtue may cost him his Reputation & even his Life. By Virtue, [I] mean an inflexible & undaunted Adherence in public Affairs to his Sentiments concerning the Interests of his Country.”8

Quaker Constitutionalism

Dickinson was influenced by the same sources that influenced other leading Founders, including classical literature, European history, English jurisprudence, and Whig political thought. But the uniqueness of his thought and action stemmed from his Quaker heritage (although it is crucial to remember that Dickinson was not a Quaker himself). Members of the Religious Society of Friends, called Quakers by their enemies, believed in universal salvation, meaning that God’s Light could shine in any properly prepared soul regardless of race, sex, or socioeconomic status. This central theological tenet differed from Calvinism—the religion of many Americans—which held that God predestined some to be saved and others to be damned. Since God’s Light was the same in every individual, Quakers also believed in human equality.9 Moreover, because God might speak through any individual, all should be allowed to preach. Over the centuries, the Quakers’ belief in spiritual equality evolved to become a belief in civil equality. Dickinson believed strongly in these Quaker concepts.

Another key tenet of Quakerism concerned how dissent should occur within the civil constitution: in other words, what a people should do if the government oppressed them. Englishmen generally had two options. Tories believed that the king could do no wrong and must not be resisted. Radical Whigs believed that oppression legitimized violent revolution. Quakers held the middle ground between the Tories and the Whigs. As pacifists, they believed that man should not destroy God’s creations, meaning not just other men, but also the civil constitution—the sacred unity of the polity, but they also advocated a new mode of resistance against brutal religious persecution in the English polity: civil disobedience, the public, nonviolent breaking of unjust laws with the intent of raising awareness of the injustice and achieving their repeal. When Dickinson advocated civil disobedience as a response to the Stamp Act, he was the first person to do so to the general public.

When Quakers had the opportunity to form and control their own government in Pennsylvania, they wrote a constitution (an unusual practice) in 1701 with an amendment clause (a novel inclusion) so that even civil disobedience would be unnecessary because a mechanism for change was built into the new plan of government. Thus, when Pennsylvania politicians Joseph Galloway and Benjamin Franklin attempted in 1764 to abolish the Quakers’ unique 1701 constitution, Dickinson sought to preserve it to protect both religious liberty and civil unity. He took the same approach in leading the resistance to Britain—using peaceful dissent to preserve the British constitution, of which America was a part. In particular, he urged civil disobedience: The colonists should conduct their “business as usual” while ignoring offending legislation, thus repealing it virtually before Parliament would repeal it actually.10

Dickinson may have been inspired by Quaker constitutionalism to contribute to another key American idea: federalism. Whereas before 1787, most Americans scoffed at the idea of divided sovereignty (a state within a state) as a monster with two heads, Dickinson seems to have envisioned exactly that as a possible solution for the problems with Britain. He continued this thinking when he drafted the 1776 Articles of Confederation with a strong central government and subordinate states. Well before the Federal Convention, he depicted that relationship as a solar system with planet-states revolving around a federal sun. In the Convention, he used the solar system metaphor to explain his solution for how representation in the legislature should work—proportional in one house and equal in the other.11

It is not likely a coincidence that Dickinson grew up within the Quaker meeting structure, which is itself a sort of federal system. Organized geographically and temporally, a group of states has an overarching, central governing body in which representatives meet once a year. This yearly meeting presides over constituent quarterly meetings covering smaller regions, which themselves are composed of representatives from local monthly meetings. At all levels, the meetings are egalitarian bureaucracies that form other bodies to accomplish the larger society’s goals. These replicating structures allowed Quakerism to expand easily from England to distant continents and from the East Coast of North America to the West.12

Freedom of the Press, Speech, and Religion

Dickinson was a lifelong champion of the fundamental rights of freedom of the press, speech, and religion. He first gained notoriety in 1758 as defense counsel for Rev. William Smith when Smith was tried for libel of the Pennsylvania Assembly by the Pennsylvania Assembly. Although it was a sham trial and Smith did not prevail, Dickinson risked his own liberty to argue for his rights. “The Freedom of the Press is truly inestimable,” he explained to the Assembly. “It is the Preserver of every other Freedom, & the Antidote to every kind of Slavery. By the Assistance of the Press, the Language of Liberty flies like Lightning thro the Land, and when the least attack is made upon her Rights, spreads the Alarm to all her Sons & raises and rouses a Whole people in her Cause.” He concluded that “Freedom of the Press is so opposite & dreadful to the Usurpers of unjust Power & the Enemies of Mankind, that Liberty however maimd & wounded still breathes & struggles, while that prevails.”13 Forty years later, Dickinson published a pamphlet critical of the Adams Administration, seemingly to test the 1798 Sedition Act.

As a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1764, Dickinson resisted the faction led by Galloway and Franklin that was seeking to remove the Penn family as proprietors of the colony and place it under royal control. Doing so would have meant abolishing the unique Pennsylvania 1701 constitution that protected liberty of conscience. Arguing eloquently to preserve that constitution, he explained that “we here enjoy that best and greatest of all rights, a perfect religious freedom.” Because Quakers refused to swear oaths, elsewhere they were excluded from participation in government. But in Pennsylvania, “posts of honour and profit are unfettered with oaths or tests.”14 For Dickinson, although religion and politics were related, “Religion and Government are certainly very different Things” and “instituted for different ends; the Design of the one being to promote our temporal Happiness; the Design of the other to procure the Favour of God, and thereby the Salvation of our Souls.” Improperly mixing them had “deluged the World in Blood.”15

Dickinson married freedom of religion with freedom of speech in his 1776 draft of the Articles of Confederation. He copied the religious liberty clause from the 1701 Pennsylvania constitution to freeze religious rights where they currently stood in each colony so that, although dissenters might not immediately gain more liberty, neither could they be denied the rights they currently exercised. He also made a significant change to remedy a defect he saw in the text. He initially followed the original clause, writing that “[n]o person or persons in any Colony living peaceably under the Civil Government shall be molested or prejudiced in his or their persons or Estate” but then went back and edited his work: “No person or persons in any Colony living peaceably under the Civil Government shall be molested or prejudiced in his or their persons or Estate….” Moreover, in place of “his or their,” he inserted “his or her.”

With this change, Dickinson’s draft of the Articles of Confederation was the first instance of an Anglo–American constitution protecting a fundamental right of both men and women. But he went further still. The clause continues: “for his or her religious persuasion or Practise.” When specifying that women should be allowed to practice their religion, Dickinson knew that, for Quaker women such as his wife and her female relatives, this meant public preaching. Thus, this clause protected not only women’s freedom to worship, but also their freedom of public speech, a right most women did not imagine they possessed. Though it was not, strictly speaking, illegal for women to speak in public, it was generally considered to be a masculine privilege. Therefore, this clause anticipated the First Amendment, the Fourteenth Amendment that incorporated the First against the states, and state constitutions from the late 20th century that used gender-inclusive language to protect women’s rights.16

The Rights and Welfare of Individuals

Dickinson was a leading advocate of the principles of individual rights stated in the Declaration of Independence even before that document was issued. For example, his concern for improving the situation of women and protecting their rights did not begin with his attempt to protect their freedom of religion and public speech in the Articles of Confederation. Rather, it stemmed from his Quakerly beliefs and close relationships with and admiration for the women in his life. His circle of highly educated female friends and relatives was notably wide and included such luminaries as Susanna Wright, Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, Mercy Otis Warren, and Catharine Macaulay. His erudite and virtuous Quaker mother was a significant influence on him, as was his literary and strong-willed Quaker wife and her many female Quaker relatives who lived with her at the Norris estate and wrote poetry objecting to the inequality of the sexes and the strictures men and a male-dominated society placed on women.17

When John and Polly married, John simply moved in with Polly and joined the Quaker poets’ sorority. His daughter inspired his closer adherence to Quakerism. Owing at least in part to their influence, he was acutely aware of the difficulties women faced in a society in which a woman’s legal identity was subsumed under her husband’s. She had few rights or responsibilities. Dickinson was especially solicitous of poor widows, arguing on their behalf in court and personally providing them with the necessities of life. As president of Pennsylvania, he proposed legislation that would allow women to divorce and receive alimony, and he counseled his daughters never to give any part of their inheritance to a husband.18

Before the Founding and during all of its phases, Dickinson paid special attention to ordinary laboring people without property. In his capacities as statesman, lawyer, and private citizen, he tried to raise up downtrodden and misfortunate individuals. He did this through legislation he wrote and championed throughout his life; pro bono work in his law practice; and philanthropy directed to immigrants, soldiers and veterans, and families of deceased religious ministers. With the help of Benjamin Rush and the Quakers, he founded what is now called the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the first prison reform organization.

Normally, elites believed that people low in the socioeconomic hierarchy did not possess enough virtue to be included in the political process. Nowhere did they have the right to vote. However, in the Farmer’s Letters, Dickinson spoke particularly to the “lower sort” to educate them about the issues of the day. He invited them to contribute to the discussion, saying that although a person might be poor, “let not any honest Man suppress his Sentiments concerning Freedom, however small their Influence is likely to be.”19 Arguing for ratification of the Constitution in 1788, he said, “What concerns all, should be considered by all; and individuals may injure a whole society, by not declaring their sentiments. It is therefore not only their right, but their duty, to declare them.”20

Dickinson also attempted to secure rights for African Americans. Although he had benefited from the institution of slavery and had inherited many enslaved people from his father, he long disliked the institution and the mistreatment of black people. As speaker of the Delaware Assembly at the age of 28, he passed legislation protecting free black people from enslavement, imposing significant fines both on the white enslavers and on the law enforcement officers who assisted them.21 He began to object to slavery publicly beginning in the early 1770s and suggested that it be outlawed in the new United States and Pennsylvania.22 At the earliest opportunity after adoption of the Declaration of Independence, he began the process of freeing the people he enslaved. In 1777, he freed them conditionally upon 21 additional years of service, but his conscience nagged at him, so he freed some unconditionally in 1781 and the remainder in 1786. He then tried multiple times to achieve abolition of slavery in Delaware, but all of his attempts failed. He continued to support elderly, formerly enslaved people for the remainder of their lives.23

Civic Education

Education of young people was a lifelong interest for Dickinson, and one of his most lasting contributions to ordinary Americans was providing them with an education. He had always valued his own liberal education, which he credited with inculcating in him critical thinking, open-mindedness, humility, and a recognition of human equality.24 Even before he had his own children and throughout much of his life, Dickinson was legal guardian of the children of several deceased family friends. Sometimes he took them into his home; sometimes they were placed in other homes. They always received an education, as did many other individuals who applied to Dickinson for assistance. His law practice was a veritable law school for young men in Philadelphia where, following his own mentors, he assigned them work not just in the law books, but also in literature, history, and the classics. When he refused Polly’s request to get married under the care of the Quaker meeting, he lectured her on the benefits of open-mindedness that come from a liberal education rather than the contracted habits of thought created by the Quakers’ “guarded” education.

But more than these efforts relating to individuals, Dickinson and his wife sought to use their vast wealth for the benefit of the least fortunate in society—orphans and children experiencing poverty. They donated land, building materials, and books for schools around the Delaware Valley. In 1796, Dickinson authored a treatise on his ideas of education for youth as a sublime pairing of religious faith and scientific knowledge.

The Dickinsons’ two lasting achievements were Dickinson College, founded in their name by Benjamin Rush, and Westtown School, a Quaker boarding school. Their vision for both was to give students a liberal arts education, which to them meant instruction in the classical languages and literature, history, science, and religion. Their aim was to create virtuous citizens who could contribute productively to American democracy and live peaceably in a religiously diverse society. To Dickinson College, they donated 600 acres in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and a library’s worth of books. Dickinson was also the president of the board of trustees. However, the Dickinsons seem to have become disenchanted with the institution, possibly because of curricular disagreements with Rush, who preferred “useful learning” to the liberal arts, which may explain why they stopped supporting the institution financially. They had a similar conflict with the Quakers over Westtown. The Dickinsons had proposed a boarding school in Chester County, Pennsylvania, for needy children of all backgrounds, insisting on a liberal arts curriculum. The Quakers objected, wanting to protect children from sin with a “guarded education.” They refused to take the Dickinsons’ donations for a decade before finally relenting.

Both Dickinson College and Westtown School flourish today, but Dickinson knew that private efforts for civic education would not be enough. “I look upon the protection of education by government,” he wrote to Benjamin Rush, “as indispensably necessary for… advancing the happiness of our fellow citizens as individuals and for securing the continuance of equal liberty to them in society.”25

The Independence Decision

Dickinson’s refusal to vote on or sign the Declaration of Independence has perplexed and even angered historians for centuries. They have not understood someone who would lead Americans in resistance to Britain and then voluntarily give up his power and influence on the eve of American greatness, but they wrote from a vantage point of knowing the outcome of the Revolution, forgetting that no one on the eve of independence did.

Dickinson did not want American independence from Britain for several quite rational reasons—some practical, others ideological. Most obviously, America was unprepared to wage war against the world’s most powerful military or to function as an independent nation. Contrary to Dickinson’s strategic bluster in the 1775 Declaration on Taking Up Arms, America’s military was immature and untested, in addition to which the country lacked the means to manufacture weapons or munitions at scale as well as foreign support, a unified populace, and a constitution. Dickinson also knew that the people of Pennsylvania—his constituents—were evenly divided on the question of independence and that many more in the Lower Counties were opposed.

Moreover, Dickinson believed that independence was unnecessary. In his speech against it, he argued that when the British lost a couple of campaigns, they would give Americans everything they had sought in their 1774 Petition to the King. He was not wrong. In 1778, after humiliation in the 1777 Battle of Saratoga, the British dispatched a commission to treat with the Americans and accede to all their demands. Dickinson informed them that nothing short of their acknowledgment of America’s independence would suffice.

Dickinson worried for Americans in another way. He thought both war and the threatened loss of the British constitution exposed the rights of the most vulnerable Americans to injury. In particular, he believed that Quakers in Pennsylvania would be persecuted by whichever side prevailed in the war—by the Anglicans if the British won or the Presbyterians if America dominated. This concern is why he wrote an extensive religious liberty clause into his draft of the Articles of Confederation.

Again, he was proven correct. When Quakers refused to engage in displays of patriotism, they were harassed in the streets, and their property was destroyed. In 1777, with John Adams in the lead, Congress acted on a suggestion by Thomas Paine to arrest all the leading Quakers in Philadelphia. Some were Polly’s relatives. They were exiled to Virginia for nine months, during which time some died and their businesses and families languished. The following year, when approximately 130 confessed Loyalists turned themselves in to the Pennsylvania authorities, the only two who were executed were also the only Quakers among them.26

Dickinson also worried about black people. He had taken notice when Somerset v. Stewart (1772), which held that slavery was incompatible with the common law, was decided in England. He had lamented what he considered to be the illegitimate American laws that allowed slavery and began to speak out against the institution and trade. Evidence suggests that Dickinson believed that black people, like religious dissenters, might have a better chance for protection of their most basic rights under the British constitution than under an as-yet-undecided American one.27

On an ideological level, Dickinson was an adherent of Quaker constitutionalism. Of paramount importance in this theologico-political theory was the unity of the polity, or the constitution of the people. Quakers believed that in order to discern God’s will, the sacred constitution must remain intact and dissent must be peaceful. Thus, he counseled against American independence—a move that, from his perspective, would have rent the unity of the British polity and precipitated untold violence throughout the land. But when Dickinson had to choose his primary identity—British or American—he had always been first and foremost an American. Thus, when forced to decide whether to stay with the British constitution or place his faith in an American one, there was no contest. He then withdrew his objection to independence and supported the cause.

Although waging war, even a defensive one, is forbidden by Quakers, Dickinson’s choice to adhere to the decision of Congress otherwise could hardly have been more Quakerly. In the Quaker meeting, after a dissenter has spoken his or her piece and the meeting decides to take a different course, that individual is obliged to step aside and support the meeting in the direction it has chosen. When it was clear that Congress had decided against his position, Dickinson stepped aside. Then he supported the decision by leading his men to the New Jersey front to fight the British. As he explained it,

Though I spoke my sentiments freely, as an honest man ought to do, yet, when a determination was reached upon the question against my opinion, I received that determination as the sacred voice of my country, as a voice that proclaimed her destiny, in which, by every impulse of my soul, I was resolved to share, and to stand or fall with her in that plan of freedom which she had chosen.28

In word and deed, John Dickinson exemplified virtuous democratic deliberation and participation. Disdaining personal advantage, he served his country for over 40 years, encouraging his countrymen to defend their rights and speaking truth to power on behalf of themselves and those who could not advocate for themselves. He recommended to Americans his own way of realizing the foundational principles stated in the Declaration of Independence: “[W]e never consult our own happiness more effectually,” he explained, “than when we most endeavour to correspond with the Divine designs, by communicating happiness, as much as we can, to our fellow-creatures.”29

Selected Primary Writings

“Friends and Countrymen” (November 1765)30

THE critical Time is now come, when you are reduced to the Necessity of forming a Resolution, upon a Point of the most alarming Importance that can engage the Attention of Men. Your Conduct at this Period must decide the future Fortunes of yourselves, and of your Posterity—must decide, whether Pennsylvanians, from henceforward, shall be Freemen or Slaves. So vast is the Consequence, so extensive is the Influence of the Measures you shall at present pursue. May God grant that every one of you may consider your Situation with a Seriousness and Sensibility becoming the solemn Occasion; and that you may receive this Address with the same candid and tender Affection for the public Good by which it is dictated.

We have seen the Day on which an Act of Parliament, imposing Stamp Duties on the British Colonies in America, was appointed to take Effect; and we have seen the Inhabitants of these Colonies, with an unexampled Unanimity, compelling the Stamp-Officers throughout the Provinces to resign their Employments. The virtuous Indignation with which they have thus acted, was inspired by the generous Love of Liberty, and guided by a perfect Sense of Loyalty to the best of Kings, and of Duty to the Mother Country. The Resignation of the Officers was judged the most effectual and the most decent Method of preventing the Execution of a Statute, that strikes the Axe into the Root of the Tree, and lays the hitherto flourishing Branches of American Freedom, with all its precious Fruits, low in the Dust.—

That this is the fatal Tendency of that Statute, appears from Propositions so evident, that he who runs may read and understand. To mention them is to convince. Men cannot be happy, without Freedom; nor free, without Security of Property; nor so secure, unless the sole Power to dispose of it be lodged in themselves; therefore no People can be free, but where Taxes are imposed on them with their own Consent, given personally, or by their Representatives. If then the Colonies are equally intitled to Happiness with the Inhabitants of Great-Britain, and Freedom is essential to Happiness, they are equally intitled to Freedom. If they are equally intitled to Freedom, and an exclusive Right of Taxation is essential to Freedom, they are equally intitled to such Taxation.

What further Steps you can now take, without Injury to this sacred Right, demands your maturest Deliberation.

IF you comply with the Act, by using Stamped Papers, you fix, you rivet perpetual Chains upon your unhappy Country. You unnecessarily, voluntarily establish the detestable Precedent, which those who have forged your Fetters ardently wish for, to varnish the future Exercise of this new claimed Authority. You may judge of the Use that will be made of it, by the Eagerness with which the Pack of Ministerial Tools have hunted for Precedents to palliate the Horrors of this Attack upon American Freedom. After all their infamous Labour, they could find nothing that even their unlimited Audacity could dare to call Precedents in this Case, but the Statute for establishing a Post-Office in America, and the Laws for regulating the Forces here, during the late War.

These Instances were greedily seized upon, and the Press groaned with Pamphlets to prove, that they would justify the Taxation of America by Great-Britain.— But no sooner were these boasted Examples produced to public View, and examined, than the Absurdity of applying them to the present Occasion, appeared so glaring, that they became more the Subject of Ridicule, than of Argument.—

Your Compliance with this Act, will save future Ministers the Trouble of reasoning on this Head, and your Tameness will free them from any Kind of Moderation, when they shall hereafter meditate any other Taxations upon you.

They will have a Precedent furnished by yourselves, and a Demonstration that the Spirit of Americans, after great Clamour and Bluster, is a most submissive servile Spirit.— Ministers will rejoice in the Discovery, and as no Measure can be more popular at Home, than to lessen the Burthens of the People there, by laying Part of the Weight on you, they will of Course be tempted by that Motive, and emboldened by your Conduct, to make you “Hewers of Wood, and Drawers of Water.”

The Stamp Act, therefore, is to be regarded only as an Experiment of your Disposition. If you quietly bend your Necks to that Yoke, you prove yourselves ready to receive any Bondage to which your Lords and Masters shall please to subject you. Some Persons perhaps may fondly hope, it will be as easy to obtain a Repeal of the Stamp Act after it is put in Execution, as if the Execution of it is avoided. But be not deceived. The late Ministry publickly declared, “that it was intended to establish the Power of Great-Britain to tax the Colonies.” Can we imagine then, that when so great a Point is carried, and we have tamely submitted, that any other Ministry will venture to propose, or that the Parliament will consent to pass, an Act to renounce this Advantage? No! Power is of a tenacious Nature: What it seizes it will retain.

Rouse yourselves therefore, my dear Countrymen. Think, oh! think of the endless Miseries you must entail upon yourselves, and your Country, by touching the pestilential Cargoes that have been sent to you. Destruction lurks within them.— To receive them is Death—is worse than Death—it is SLAVERY!— If you do not, and I trust in Heaven you will not use the Stamped Papers, it will be necessary to consider how you are to act. Some Persons are of Opinion, that it is proper to stop all Business that requires written Instruments, subject to Duties.

Against this Proposal there are many weighty Objections. In the first Place, it will be nearly the same Acknowledgment of the Validity of the Stamp Act, and of its legal Obligation upon you, as if you use the Papers. It will also be extremely injurious to Individuals, and I apprehend the Inconveniences arising from the Stoppage of Business will be so great, that many People, whose immediate Interest may have too much Influence on their Judgment, may be induced to believe, that this Obstruction will be more pernicious than the Execution of the Stamp Act; and thus I am afraid, that a mistaken Zeal to avoid the Execution, may really produce it. How long can this Stoppage be endured? Or how long must it be continued? Until we can obtain Relief, by a Repeal of the Law, perhaps some may say. If this should happen, you cannot expect to hear of the Repeal in less than three or four Months. But if you act in this Manner, in my Opinion, you will never hear of it. For as soon as the News of your stopping all Business arrives in Great-Britain, the Parliament, Ministry and People, will be convinced of two Things: first, that you are intimidated to the utmost Degree; and secondly, that your Method of eluding the Act will at length compel you to comply with it.— They will therefore give themselves no further Trouble about you, unless it be to send over a few Regiments, to quicken the Execution.

For these Reasons, and many more, it appears to me the wisest and the safest Course for you to proceed in all Business as usual, without taking the least Notice of the Stamp Act. If you behave in this spirited Manner, you may be assured, that every Colony on the Continent will follow the Example of a Province so justly celebrated for its Liberty. Your Conduct will convince Great-Britain, that the Stamp Act will never be carried into Execution, but by Force of Arms; and this one Moment’s Reflection must demonstrate, that she will never attempt.

As to any Penalties that may be incurred, it will be vain to think of extorting them from the whole Continent, or from a whole Province. It may be objected, perhaps, that our Ships will be liable to Seizure, if their Clearances be not upon Stamped Papers; but I believe no Lawyer will say, that this would be a legal Reason for such Seizures. However, we need be under no Apprehension of this Kind; for proceeding in that Way, would be in Fact a Declaration of War against the Colonies, that at this Time would by no Means suit the Mother Country.—

Thus, my Friends and Countrymen, have I plainly laid before you my Sentiments on your present affecting Situation; and may Divine Providence inspire you with Wisdom to act in such a Manner, as will most advance that Happiness I ardently wish you may enjoy.

“Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, Letter III” (December 14, 1767)31

I rejoice to find, that my two former letters to you, have been generally received with so much favour by such of you, whose sentiments I have had an opportunity of knowing. Could you look into my heart, you would instantly perceive an ardent affection for your persons, a zealous attachment to your interests, a lively resentment of every insult and injury offered to your honour or happiness, and an inflexible resolution to assert your rights, to the utmost of my weak power, to be the only motives that have engaged me to address you.

I am no further concerned in any thing affecting America, than any one of you; and when liberty leaves it, I can quit it much more conveniently than most of you: But while Divine Providence, that gave me existence in a land of freedom, permits my head to think, my lips to speak, and my hand to move, I shall so highly and gratefully value the blessing received, as to take care, that my silence and inactivity shall not give my implied assent to any act, degrading my brethren and myself from the birthright, wherewith heaven itself “hath made us free.”

Sorry I am to learn, that there are some few persons, who shake their heads with solemn motion, and pretend to wonder, what can be the meaning of these letters. “Great-Britain,” they say, “is too powerful to contend with; she is determined to oppress us; it is in vain to speak of right on one side, when there is power on the other; when we are strong enough to resist, we shall attempt it; but now we are not strong enough, and therefore we had better be quiet; it signifies nothing to convince us that our rights are invaded, when we cannot defend them; and if we should get into riots and tumults about the late act, it will only draw down heavier displeasure upon us.”

What can such men design? What do their grave observations amount to, but this—“that these colonies, totally regardless of their liberties, should commit them, with humble resignation, to chance, time, and the tender mercies of ministers.”

Are these men ignorant, that usurpations, which might have been successfully opposed at first, acquire strength by continuance, and thus become irresistible? Do they condemn the conduct of these colonies, concerning the Stamp-Act? Or have they forgot its successful issue? Ought the colonies at that time, instead of acting as they did, to have trusted for relief, to the fortuitous events of futurity? If it is needless “to speak of rights” now, it was as needless then. If the behaviour of the colonies was prudent and glorious then, and successful too; it will be equally prudent and glorious to act in the same manner now, if our rights are equally invaded, and may be as successful. Therefore it becomes necessary to enquire, whether “our rights are invaded.” To talk of “defending” them, as if they could be no otherwise “defended” than by arms, is as much out of the way, as if a man having a choice of several roads to reach his journey’s end, should prefer the worst, for no other reason, but because it is the worst.

As to “riots and tumults,” the gentlemen who are so apprehensive of them, are much mistaken, if they think, that grievances cannot be redressed without such assistance.

I will now tell the gentlemen, what is “the meaning of these letters.” The meaning of them is, to convince the people of these colonies, that they are at this moment exposed to the most imminent dangers; and to persuade them immediately, vigorously, and unanimously, to exert themselves, in the most firm, but most peaceable manner, for obtaining relief.

The cause of liberty is a cause of too much dignity, to be sullied by turbulence and tumult. It ought to be maintained in a manner suitable to her nature. Those who engage in it should breathe a sedate, yet fervent spirit, animating them to actions of prudence, justice, modesty, bravery, humanity and magnanimity.

To such a wonderful degree were the ancient Spartans, as brave and free a people as ever existed, inspired by this happy temperature of soul, that rejecting even in their battles the use of trumpets, and other instruments for exciting heat and rage, they marched up to scenes of havock and horror, with the sound of flutes, to the tunes of which their steps kept pace—“exhibiting,” as Plutarch says, “at once a terrible and delightful sight, and proceeding with a deliberate valour, full of hope and good assurance, as if some divinity had sensibly assisted them.”

I hope, my dear countrymen, that you will, in every colony, be upon your guard against those, who may at any time endeavour to stir you up, under pretences of patriotism, to any measures, disrespectful to our Sovereign and our mother country. Hot, rash, disorderly proceedings, injure the reputation of a people, as to wisdom, valour and virtue, without procuring them the least benefit. I pray GOD, that he may be pleased to inspire you and your posterity, to the latest ages, with that spirit of which I have an idea, but find a difficulty to express. To express it in the best manner I can, I mean a spirit, that shall so guide you, that it will be impossible to determine whether an American’s character is most distinguishable, for his loyalty to his Sovereign, his duty to his mother country; his love of freedom, or his affection for his native soil.

Every government at some time or other falls into wrong measures. These may proceed from mistake or passion. But every such measure does not dissolve the obligation between the governors and the governed. The mistake may be corrected; the passion may pass over. It is the duty of the governed to endeavour to rectify the mistake, and to appease the passion. They have not at first any other right, than to represent their grievances, and to pray for redress, unless an emergence is so pressing, as not to allow time for receiving an answer to their applications, which rarely happens. If their applications are disregarded, then that kind of opposition becomes justifiable, which can be made without breaking the laws, or disturbing the public peace. This consists in the prevention of the oppressors reaping advantage from their oppressions, and not in their punishment. For experience may teach them, what reason did not; and harsh methods cannot be proper, till milder ones have failed.

If at length it becomes undoubted, that an inveterate resolution is formed to annihilate the liberties of the governed, the English history affords frequent examples of resistance by force. What particular circumstances will in any future case justify such resistance, can never be ascertained, till they happen. Perhaps it may be allowable to say generally, that it never can be justifiable, until the people are fully convinced, that any further submission will be destructive to their happiness.

When the appeal is made to the sword, highly probable is it, that the punishment will exceed the offence; and the calamities attending on war out-weigh those preceding it. These considerations of justice and prudence, will always have great influence with good and wise men.

To these reflections, on this subject, it remains to be added, and ought for ever to be remembered, that resistance, in the case of colonies against their mother country, is extremely different from the resistance of a people against their prince. A nation may change their king, or race of kings, and, retaining their ancient form of government, be gainers by changing. Thus Great-Britain, under the illustrious house of Brunswick, a house that seems to flourish for the happiness of mankind, has found a felicity, unknown in the reigns of the Stewarts. But if once we are separated from our mother country, what new form of government shall we adopt, or where shall we find another Britain, to supply our loss? Torn from the body, to which we are united by religion, liberty, laws, affections, relation, language and commerce, we must bleed at every vein.

In truth—the prosperity of these provinces is founded in their dependance on Great-Britain; and when she returns to her “old good humour, and her old good nature,” as Lord Clarendon expresses it, I hope they will always think it their duty and interest, as it most certainly will be, to promote her welfare by all the means in their power.

We cannot act with too much caution in our disputes. Anger produces anger; and differences, that might be accommodated by kind and respectful behaviour, may, by imprudence, be enlarged to an incurable rage. In quarrels between countries, as well as in those between individuals, when they have risen to a certain height, the first cause of dissension is no longer remembered, the minds of the parties being wholly engaged in recollecting and resenting the mutual expressions of their dislike. When feuds have reached that fatal point, all considerations of reason and equity vanish; and a blind fury governs, or rather confounds all things. A people no longer regards their interest, but the gratification of their wrath. The sway of the Cleons and Clodius’s, the designing and detestable flatterers of the prevailing passion, becomes confirmed. Wise and good men in vain oppose the storm, and may think themselves fortunate, if, in attempting to preserve their ungrateful fellow citizens, they do not ruin themselves. Their prudence will be called baseness; their moderation guilt; and if their virtue does not lead them to destruction, as that of many other great and excellent persons has done, they may survive to receive from their expiring country the mournful glory of her acknowledgment, that their counsels, if regarded, would have saved her.

The constitutional modes of obtaining relief, are those which I wish to see pursued on the present occasion; that is, by petitions of our assemblies, or where they are not permitted to meet, of the people, to the powers that can afford us relief.

We have an excellent prince, in whose good dispositions towards us we may confide. We have a generous, sensible and humane nation, to whom we may apply. They may be deceived. They may, by artful men, be provoked to anger against us. I cannot believe they will be cruel or unjust; or that their anger will be implacable. Let us behave like dutiful children, who have received unmerited blows from a beloved parent. Let us complain to our parent; but let our complaints speak at the same time the language of affliction and veneration.

If, however, it shall happen, by an unfortunate course of affairs, that our applications to his Majesty and the parliament for redress, prove ineffectual, let us then take another step, by withholding from Great-Britain all the advantages she has been used to receive from us. Then let us try, if our ingenuity, industry, and frugality, will not give weight to our remonstrances. Let us all be united with one spirit, in one cause. Let us invent—let us work—let us save—let us, at the same time, keep up our claim, and incessantly repeat our complaints— But, above all, let us implore the protection of that infinitely good and gracious being, “by whom kings reign, and princes decree justice.”

Nil desperandum.

Nothing is to be despaired of.

Recommended Readings

- Jane E. Calvert, Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Jane E. Calvert, Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024).

- Jane E. Calvert, ed., The Complete Writings and Selected Correspondence of John Dickinson (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2020– ).

- Richard Alan Ryerson, “The Revolution Is Now Begun”: The Radical Committees of Philadelphia, 1765–1776 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978).

- Charles J. Stillé, The Life and Times of John Dickinson, 1732–1808 (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1891).

- Frederick Tolles, “John Dickinson and the Quakers,” in “John and Mary’s College”: The Boyd Lee Spahr Lectures in Americana (Westwood, NJ: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1956), pp. 67–88.

Notes

[1] John Dickinson to Mary Cadwalader Dickinson, January 22, 1755, in The Complete Writings and Selected Correspondence of John Dickinson, ed. Jane E. Calvert (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2020–), Vol. 1, p. 74, https://www.jdproject.org/_files/ugd/fc1edd_4dde387737094977b8e95a51aa57856b.pdf (accessed May 1, 2025) (hereinafter Complete Writings).

[2] See John Dickinson to Mary Cadwalader Dickinson, May 25, 1754, and February 19, 1755, in Complete Writings, Vol. 1, pp. 36 and 77.

[3] Kenneth R. Bowling, “New Light on the Philadelphia Mutiny of 1783: Federal–State Confrontation at the Close of the War for Independence,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 101, No. 4 (October 1977), pp. 442–443.

[4] See The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, ed. Max Farrand (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911), Vol. 1, p. 87, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1057/0544-01_Bk.pdf (accessed April 17, 2025) (hereinafter Farrand, Debates). Although Roger Sherman is usually credited with this solution, Forrest McDonald recognized that “Dickinson alone” initially perceived how this system could work. See Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1985), p. 215.

[5] John Dickinson to Mary Cadwalader Dickinson, March 8, 1754, in Complete Writings, Vol. 1, p. 17.

[6] John Dickinson to Unknown, n.d., Logan Family Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[7] John Dickinson, “Arguments Against the Independence of these Colonies” [July 1, 1776], Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Gratz Autograph Collection.

[8] Ibid.

[9] On Quaker theology, see Geoffrey Durham, The Spirit of the Quakers (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). On Calvinist theology, see Perry Miller, Errand into the Wilderness (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1956).

[10] John Dickinson, “Friends and Countrymen,” 1765, in Complete Writings, Vol. 3, p. 376, https://www.jdproject.org/_files/ugd/fc1edd_682c269c9c5f478fa65bdfd3db023ed5.pdf (accessed May 1, 2025).

[11] Farrand, Debates, Vol. 1, p. 153.

[12] See Jane E. Calvert, Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 299–310.

[13] John Dickinson, “Draft Transcript of Closing Arguments for the Smith Libel Trial” [January 21, 1758], in Complete Writings, Vol. 1, p. 252. Emphasis in original.

[14] John Dickinson, A Speech, Delivered in the House of Assembly in the Province of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: William Bradford, [June 29,] 1764), in Complete Writings, Vol. 3, p. 67. Emphasis in original.

[15] A.B. [John Dickinson] and Anonymous [Francis Alison?], “The Centinel. No. VIII,” The Pennsylvania Journal, May 12, 1768, in Complete Writings, Vol. 4, forthcoming February 2026, p. 204

[16] See Jane E. Calvert, “The Friendly Jurisprudence and Early Feminism of John Dickinson,” in Great Christian Jurists in American History, ed. Daniel L. Dreisbach and Mark David Hall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 133–159.

[17] See Mary Norris Dickinson et al., “The Rural-Circle, or Band of Friendship, in Familiar Letters Between Several Young Ladies, Interspers’d with a Variety of Valuable Characters” [c. 1760–1768], Library Company of Philadelphia, Dickinson Family Papers; Milcah Martha Moore’s Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America, ed. C. La Courreye Blecki and K.A. Wulf (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997).

[18] See Jane E. Calvert, Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024). pp. 157–161, 336, 416.

[19] A Farmer [John Dickinson], “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. Letter I,” 1767, in Complete Writings, Vol. 4, p. 31.

[20] Fabius [John Dickinson], “Observations on the Constitution Proposed by the Federal Convention, No. 1,” The Pennsylvania Mercury, April 12, 1788. Emphasis in original.

[21] Calvert, Penman of the Founding, pp. 117–118.

[22] Ibid., pp. 215–216, 264, 274.

[23] Ibid., pp. 303, 346–47, 380–385.

[24] Ibid., pp. 62–63, 196–197. See also Complete Writings, Vol. 1, esp. the “London Letters.”

[25] John Dickinson to Benjamin Rush, February 14, 1791, New York Public Library, Bancroft Transcripts.

[26] Peter C. Messer, “‘A Species of Treason & Not the Least Dangerous Kind’: The Treason Trials of Abraham Carlisle and John Roberts,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 123, No. 4 (October 1999), pp. 303–332.

[27] Calvert, Penman of the Founding, pp. 215–217, 264, 274, 283–286, 303, 346–347. See also Jane E. Calvert, “Black Freedom and Its Limits in the Thought of John Dickinson,” in 1776 or 1619: The Challenge of the American Founding, ed. Michael Poliakoff (forthcoming).

[28] John Dickinson, “To My Opponents,” Freeman’s Journal, January 1, 1783.

[29] Fabius [John Dickinson], “Observations on the Constitution Proposed by the Federal Convention, No. III,” The Pennsylvania Mercury, and Universal Advertiser, April 17, 1788.

[30] Dickinson, “Friends and Countrymen,” in Complete Writings, Vol. 3, pp. 374–377.

[31] A Farmer [John Dickinson], “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, Letter III,” December 17, 1767, in Complete Writings, Vol. 4, pp. 52–56. Emphasis in original. Footnotes omitted.