—Richard Stockton, New Jersey delegate to the Second Continental Congress, c. 17761

Life

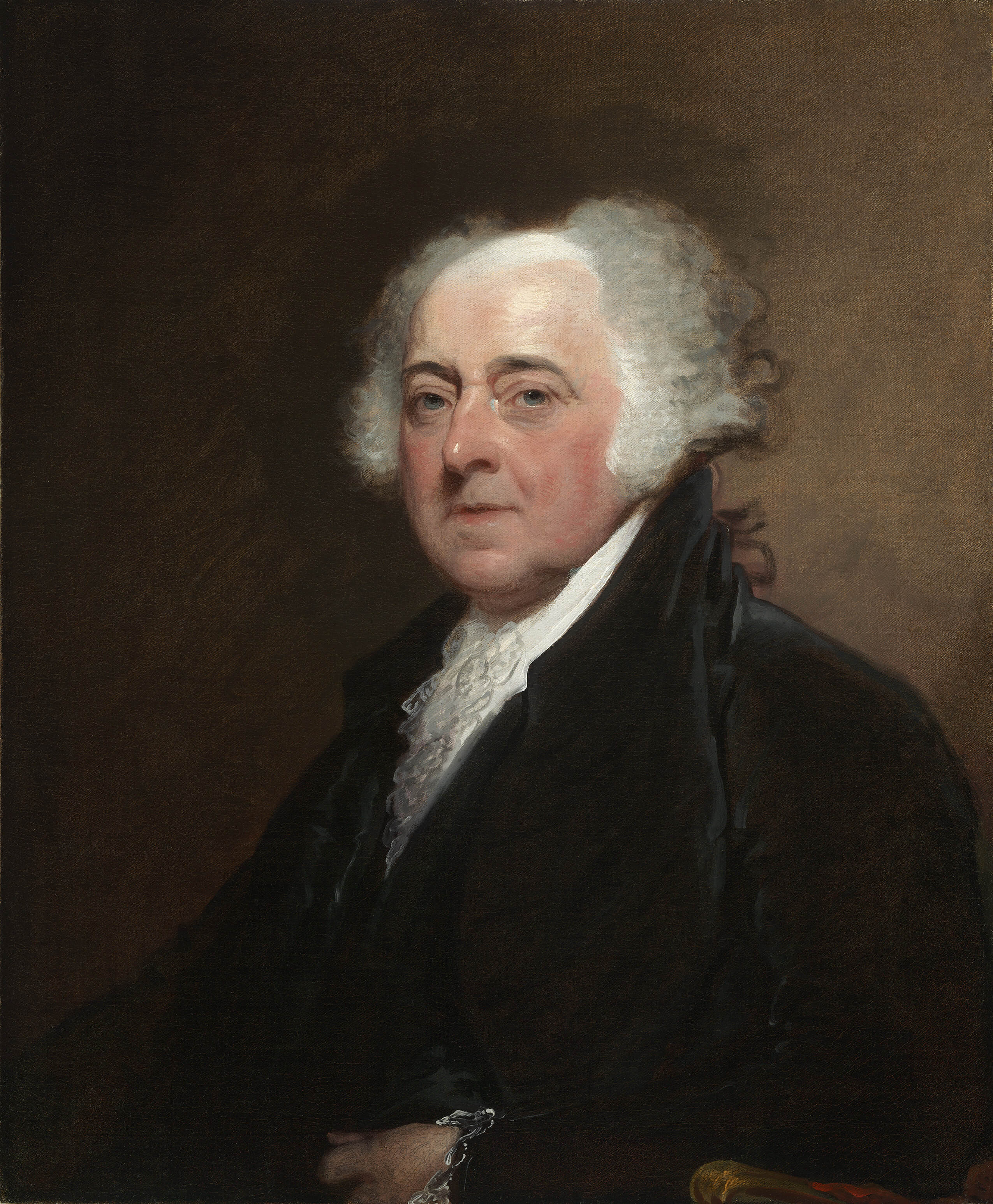

John Adams was born October 19, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts, the eldest son of John Adams Sr. and Susanna Boylston Adams. His father was a farmer, shoemaker, and deacon. He had two younger brothers, Peter and Elihu. Adams married Abigail Smith (1744–1818) on October 25, 1764. They had four surviving children: Abigail, John Quincy, Charles, and Thomas. John Adams died July 4, 1826, at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Education

Adams was educated first at home and then in a neighborhood home school; he graduated from Harvard College with a bachelor’s degree in 1755.

Religion

Congregational/Unitarian

Political Affiliation

Federalist Party

Highlights and Accomplishments

1774–1775: Author, Novanglus Letters

1774–1777: Continental Congress

1775–1777: Justice, Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature

1776: Author, Thoughts on Government

1780: Author, Massachusetts Constitution

1782–1788: First United States Minister to the Netherlands

1785–1788: First United States Minister to Great Britain

1786–1787: Author, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America

1789–1797: First Vice President of the United States

1790: Author, Discourses on Davila

1797–1801: Second President of the United States

John Adams is often overlooked as one of America’s greatest Revolutionary statesmen, yet he was widely regarded as the most learned and penetrating thinker of his generation and played a central role in the American Founding. “The man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of independence is Mr. John Adams,” one delegate to the Second Continental Congress wrote. “I call him the Atlas of American independence.”2

Adams witnessed the American Revolution from beginning to end: In 1761, he assisted James Otis in defending Boston merchants against enforcement of Britain’s Sugar Act, and in 1783, he participated in negotiating the peace treaty with Britain. He was a key leader of the radical political movement in Boston and one of the earliest and most principled voices for independence at the Continental Congress. As a public intellectual, he wrote some of the most important and influential essays, constitutions, and treatises of the Revolutionary period. If Revolutionary leaders like Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry represent the spirit of the independence movement, John Adams exemplifies the mind of the American Revolution.

Of his many significant qualities and contributions to the American Founding, three are most important: his character, constitutional development, and principles of political architecture.

The Life of Adams

John Adams was born on October 19, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts. His life and moral virtues were shaped early by the manners and mores of a New England culture that honored sobriety, industry, thrift, simplicity, and diligence.

After graduating from Harvard College, Adams taught school for three years and began to read for a career in the law. He was admitted to the Boston bar in 1758 and soon settled into a flourishing law practice. In 1764, he married Abigail Smith, to whom he was devoted for 54 years. Together they had five children, including John Quincy Adams, who became the sixth President of the United States.

Passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 thrust Adams into the public affairs of the colonies and the British Empire. In that year, he published his first major political essay, A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, attacking the Stamp Act for depriving the American colonists of two basic rights guaranteed to all Englishmen by Magna Carta: the right to be taxed only by consent and the right to be tried only by a jury of one’s peers.

Between 1765 and 1776, Adams’s involvement in radical politics ran apace with the escalation of events. He was a leader of the radical political movement in Boston, and his Novanglus letters are generally regarded as the best expression of the American case against parliamentary sovereignty. By the mid-1770s, Adams had distinguished himself as one of America’s foremost constitutional scholars.

The year 1774 was critical in British–American relations, and it proved to be a momentous one for John Adams. With Parliament’s passage of the Coercive Acts, Adams realized that the time had come for the Americans to invoke what he called “revolution principles.”3 Later that year, he was elected to the First Continental Congress. Over the course of the next two years, no man worked as hard or played as important a role in the movement for independence. His first great contribution to the American cause was to draft the principal clause of the Declaration of Rights and Grievances in October 1774. He also chaired the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence; drafted America’s first Model Treaty; and, working 18-hour days, served as a one-man department of War and Ordnance. In the end, he worked tirelessly on some 30 committees.

Shortly after the battles at Lexington and Concord, Adams began to argue that the time had come for the colonies to declare independence and constitutionalize the powers, rights, and responsibilities of self-government. In May 1776, due in large measure to Adams’s labors, Congress passed a resolution recommending that the various colonial assemblies draft constitutions and construct new governments. At the request of several colleagues, Adams wrote his own constitutional blueprint. Published as Thoughts on Government, the pamphlet was circulated widely, and constitution-makers in at least four states used its design as a working model for their state constitutions.

Adams’s greatest moment in Congress came in the summer of 1776. On July 1, Congress considered final arguments on the question of independence, and John Dickinson, a delegate from Pennsylvania, argued forcefully against it. When no one responded to Dickinson, Adams rose and delivered a rhetorical tour-de-force that moved the assembly to vote in favor of independence. Years later, Thomas Jefferson recalled that Adams’s speech was so powerful in “thought & expression” that it “moved us from our seats.” He was, Jefferson said, “our Colossus on the floor.”4

In the fall of 1779, Adams drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, which was the most impressive constitution produced during the Revolutionary era. It was copied by other states in later years and was an influential model for the Framers of the federal Constitution of 1787.

Adams spent much of the 1780s in Europe as a diplomat and propagandist for the American Revolution. He succeeded in convincing the Dutch Republic to recognize American independence and negotiated critical loans with Amsterdam bankers. In 1783, he joined Benjamin Franklin and John Jay in Paris and played an important role in negotiating a treaty of peace with England. Adams completed his European tour of duty as America’s first minister to Great Britain.

It was during his time in London that Adams wrote his great treatise in political philosophy, the three-volume A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. Written as a guidebook for American and European constitution-makers, the Defence was influential at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and was used by French constitution-makers in 1789 and again in 1795.

After his return to America in 1788, Adams was twice elected Vice President of the United States. His election to the presidency in 1796 was the culmination of a long public career dedicated to the American cause. Unfortunately, the new President inherited two intractable problems from the Washington Administration: an intense ideological party conflict between Federalists and Republicans and hostile relations with an increasingly belligerent French Republic that, known as the Quasi-War, became the central focus of his Administration. Consistent with his views on American foreign policy dating back to 1776, Adams’s guiding principle was “that we should make no treaties of alliance with any European power; that we should consent to none but treaties of commerce; that we should separate ourselves, as far as possible and as long as possible, from all European politics and wars.”5 The crowning achievement of his presidency was the ensuing peace convention of 1800 that reestablished American neutrality and commercial freedom. When Adams left office and returned to Quincy in 1801, he could proudly declare that America was stronger and freer than it was on the day he took office.

The bitterness of his electoral loss to Thomas Jefferson in 1800 soon faded as Adams spent the next 25 years enjoying pleasures of domestic bliss and a newfound philosophic solitude. During his last quarter-century, he read widely in philosophy, history, and theology, and in 1812, he reconciled with Jefferson and resumed with his friend at Monticello a correspondence that is unquestionably the most impressive in the history of American letters.

Remarkably, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died on the same day: July 4, 1826, 50 years to the day after signing the Declaration of Independence.

Character Matters

Despite his extraordinary achievements, Adams has always posed a genuine problem for historians. From the moment he entered public life, he always seemed to travel the road not taken. Americans have rarely seen a political leader of such fierce independence and unyielding integrity. In debate, he was intrepid to the verge of temerity, and his political writings reveal an utter contempt for the art of dissimulation. Unable to meet falsehoods halfway and unwilling to stop short of the truth, Adams was in constant battle with the accepted, the conventional, the fashionable, and the popular.

When Adams spoke of moral goodness and right conduct, he most often had in mind the ordinary virtues associated with self-rule. Mastery of oneself, for Adams, was the indispensable foundation of a worthy life and the end to which virtues like moderation, frugality, fortitude, and industry are directed.

As a young man, John Adams was always looking inward—surveying, evaluating, and judging the state of his soul. He imposed on himself a strict daily regimen of hard work and spartan austerity. He constantly cajoled and implored himself to rise early, apply himself to a rigid system of work and study, conquer his passions, and ferret out any weaknesses in his character. A 21-year-old Adams resolved “to rise with the Sun and to study the Scriptures, on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday mornings, and to study some Latin author the other three mornings.” In addition, “Noons and Nights I intend to read English Authors. This is my fixed determination, and I will set down every neglect and every compliance with this resolution. May I blush whenever I suffer one hour to pass unimproved.”6

But he did not always succeed. In order to bolster and inflame his flagging spirit after an extended period of lethargy and weakness, Adams sketched a fable of Hercules, adapting the story to his own situation. “Let Virtue Address me,” he wrote:

Which, dear youth, will you prefer? a life of effeminacy, indolence and obscurity, or a life of industry, temperance and honor? Take my Advice…. Let no trifling diversion or amusement, or company, decoy you from your book; that is, let no girl, no gun, no cards, no flutes, no violins, no dress, no tobacco, no laziness, decoy from your books.7

The goal of self-knowledge and self-rule for Adams was rational independence in the fullest sense. He was always demanding of himself that he return to his study to tackle the great treatises and casebooks of the law:

Labor to get distinct Ideas of law, right, wrong, justice, equity. Search for them in your own mind, in Roman, Grecian, French, English Treatises of natural, civil, common, statute law. Aim at an exact knowledge of the nature, end, and means of government. Compare the different forms of it with each other, and each of them with their effects on public and private happiness. Study Seneca, Cicero, and all other good moral writers. Study Montesquieu, Bolingbroke, Vinnius, &c., and all other good, civil writers, &c.8

Like many great-souled men, John Adams was ambitious and desiring of fame, but unlike most such men, he spent a good deal of time thinking about his ambition and its relationship to his moral and political principles. The passion for fame was both an intellectual and a personal problem for Adams because it cut two ways. On the one hand, there is a kind of fame that is benevolent and noble in purpose—the kind associated with Pericles, Cato, and Washington. On the other hand, there is a passion for fame that could also serve malevolent and base ends—the kind associated with Alcibiades, Caesar, and Napoleon.

Adams understood benevolent fame to be motivated by a desire to promote the public good and to be achieved either by performing some great deed or through an act of unusual genius that benefits the commonweal. But he did not simply take the well-being or the opinion of others as his Pole Star. Ultimately, benevolent fame is connected to higher principles that the honorable man seeks for self-interested reasons. As with Aristotle’s great-souled man, such men act because they love that which is noble, good, and just for its own sake.

Never a hypocrite, Adams lived by his own words and avowed principles. He always chose to act in ways he thought right or just, regardless of reward or punishment. The linchpin that united theory and practice in Adams’s moral universe was the virtue of integrity. Success, reputation, and fame were not ends in themselves for Adams; they had to be attached to a moral principle and a noble end and to some virtuous action. He would not violate his strict code of character to achieve the favorable opinion of posterity. Above all else, John Adams was a man of strict principle, a man of unyielding integrity, a man of firm justice.

The Principles of Liberty

During his retirement years, John Adams was fond of saying that the War of Independence was only a consequence of the American Revolution. The real revolution, he declared, began 15 years before any blood was shed at Lexington as an intellectual and moral revolution in the minds and hearts of the American people. Adams played an important role in shaping this intellectual and moral revolution by articulating in his many writings a new theory of constitutional development.

In 1765, Adams responded to the Stamp Act with A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, which was principally a primer on moral education. Its purpose was to rekindle the American “spirit of liberty.”9 But what did Adams mean by a “spirit of liberty”? Spiritedness for Adams united in body and soul certain “sensations of freedom” and certain “ideas of right.”10

Adams meant to inspire the colonists’ sensations of freedom and thus guarantee present freedoms by calling for a remembrance of things past: He implored all patriots to recall the hardships endured by the first settlers and to honor their heroic deeds. On a deeper level, however, the Revolution for Adams was about certain ideas of right, so he appealed to the colonists’ reason, imploring them to study the philosophical foundations of their rights and liberties. The Americans, he wrote, have a “habitual, radical Sense of Liberty, and the highest Reverence for Vertue” that can and must be appealed to in the face of British tyranny.11

Liberty, for Adams, meant freedom from foreign domination, freedom from unjust government coercion, freedom from other individuals, and freedom from the tyranny of one’s passions. A free people ought to be jealous of their rights and liberties and must always stand on guard to protect them. Adams knew that genuine freedom is fragile, fleeting, and rare; few people have it, and those who do must fight to keep it. Ultimately, the spirit of liberty for Adams was a certain kind of virtue: It “is and ought to be a jealous, a watchful spirit.” The maxim that he chose to define the spirit of liberty was “Obsta Principiis,” meaning to resist first beginnings. He implored his fellow citizens to resist the “first approaches of arbitrary power.”12

By 1774, when Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, Adams thought that tyranny no longer threatened America from a distance—it had arrived. But how should the Americans respond? During the 1760s, Adams had attempted to foster an enlightened “spirit of liberty” as an antidote to the “spirit of subservience.” By 1774, however, the time had come for Americans to invoke what he called “revolution principles.” In that moment, Adams ceased to be a conservative defender of colonial rights and liberties and became a revolutionary republican. Adams’s “revolution principles” were guided by what he learned from “the principles of Aristotle and Plato, of Livy and Cicero, and Sidney, Harrington and Locke; the principles of nature and eternal reason; the principles on which the whole over us now stands.”13 But revolutions should not be undertaken for light and transient reasons; they must be pursued with caution, moderation, and prudence. There must be objectively definable principles and observable conditions that justify such a momentous step.

For Adams, the boundary line between resistance and revolution was the constitution. He always sought constitutional solutions to constitutional problems, but when that was no longer possible, a “recourse to higher powers not written” was entirely justified.14 However, he defended resort to what he called “original power” only when fundamental constitutional principles were at stake.15 By 1776, the British constitution was broken, unable to accommodate the new demands being placed on the colonies by the empire. Eventually Adams saw it as fundamentally flawed. In the end, resolution of the conflict between the center and the peripheries of the British Empire was not possible precisely because there was no standard, no higher or fundamental law, no written constitution by which to sort out the conflicting claims of Parliament and the colonies.

During the years of the imperial crisis, Adams developed a radically new theory that sought to identify, protect, and enshrine certain basic rights and liberties—what he called “revolution principles”—from the intrusions of government in written constitutions. As early as 1775, notably in his Thoughts on Government, Adams was arguing that new constitutions be drafted and governments established based on the consent of the governed. For Adams, a written constitution was the product not of history, custom, usage, or the “artificial reasoning” of common-law lawyers, as it was in England, but rather of philosophy and free will, reason and choice, deliberation and consent. What was radically new in all this—and today we take for granted—was that the people’s will was to be captured by special conventions to create and then ratify written constitutions. By lifting the constitutional convention above ordinary acts of legislation, Adams and his fellow revolutionaries created a process by which written constitutions could be sanctified and come to be respected and defended as fundamental law. Elaborating the stages of constitutional development—from the spirit of liberty to the principles of the Revolution to a supreme written constitution as fundamental law—may very well be Adams’s greatest contribution to America.

The Principles of Political Architecture

At the core of Adams’s political theory, elaborated in his great treatise A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, were three basic but essential principles of political architecture: representation instead of direct democracy; separation of the legislative, executive, and judicial powers; and a mixture and balance in the legislature between the one, the few, and the many—that is, a mixing of the monarchic, aristocratic, and democratic passions that Adams thought natural to all societies. The combination of these three elements was a true innovation in the history and practice of Western constitutionalism.

Adams’s three principles of political architecture were the foundation and framework on which he thought all constitutions must be constructed. The first two, representation and separation of powers, were distinctly new: Both were logically derived from Lockean natural-rights theory and its corollary theory of consent.

Legitimate political power for Adams rested on the principle of representation, which in turn rested on the more fundamental principles of consent, equality, and self-government. The purpose of political representation is to serve as a guardian of the people’s rights and liberties without being subject to their immediate passions. Separation of powers for Adams is the architectonic principle that defined, shaped, and constitutionalized the republican form of government. The purpose of the separation of powers is to dilute the inherent tendency of all governments—including republics—to centralize political power in the hands of one man or a group of men.

The third principle, however, was hardly a new idea. With its roots in the theory and practice of classical antiquity, the so-called mixed regime rested on an entirely different theoretical foundation. The theory of mixed government was a peculiarly classical notion necessarily related to the question of who should rule; separation of powers was a uniquely modern idea connected to the question of the limits or extent of rule.

From Adams’s perspective, there were two critical problems that must be addressed by all republican constitution-makers. The first was the tendency of democracies to democratize. The great danger associated with the doctrine of equality is that it can generate a downward psychological and moral momentum that is hard to resist or control, destroying old manners and mores and transforming the soul in profound ways. Adams feared that unchecked democratization would eventually liberate passions dangerous to democratic government.

The second problem is the ambition of the exceptional few. Adams was particularly fearful of those men that Abraham Lincoln later characterized as the “tribe of the eagle and the family of the lion”—that is, talented men who were consumed with political ambition. But he also understood that a healthy democratic regime must be able to recognize and appreciate the truly great individuals who elevate and ennoble self-government by reminding us of democratic greatness.

Adams’s solution was to constitutionalize the naturally occurring conflict between the exceptional few and the unexceptional many of any given society by incorporating what he called the “triple equipoise”—a mixing and balancing of the one (a president with a legislative veto); the few (a senate); and the many (a house of representatives)—into the legislative branch. His mixed-government theory would harness, channel, and balance the naturally occurring conflict between the few and the many in politically useful ways, forcing the competing social orders to moderate their passions, look beyond their immediate self-interest, and compromise with rival interests.

The mixed regime attempted to harmonize the competing and ineradicable notions of justice held by different social orders (the few and the many), and separation of powers was about preventing the centralization of government’s coercive power. Adams thought that mixed government and separation of powers could be employed together as overlapping and mutually reinforcing principles. Each order, with its incomplete view of justice, and each branch, with its separate powers, would be forced to moderate and elevate its partial claims, thereby producing and necessitating laws that were just, equitable, and ultimately for the common benefit.

Independence Forever

John Adams had an enormous influence on the outcome of the American Revolution. He dedicated his life, his property, and his sacred honor to the cause of liberty and the construction of republican government in America. The force of his reasoning, depth of his political vision, and integrity of his moral character are undeniable. From the beginning of his public career until the very end, he always acted on principle and from a profound love of country.

We may take the following words that he wrote to a friend during some of the darkest days of the Revolution as a motto to describe who he was as a man and as a patriot: “Fiat Justitia ruat Coelum”—Let justice be done though the heavens should fall.16 To live by such words requires a kind of moral independence that honors doing only what is right and just at all times. “I must think myself independent, as long as I live,” he wrote to his son John Quincy in 1815. “The feeling is essential to my existence.”17

As the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence approached, a 91-year-old Adams was asked to provide a toast for the upcoming celebration in Quincy, Massachusetts. He offered as his final public utterance this solemn toast: “INDEPENDENCE FOREVER.”18 These last words stand as a signature for his life and principles. At a time in our nation’s history when most Americans cynically assume that their political leaders are dishonest, corrupt, and self-serving, we might do well to recall the example of John Adams and restore to posterity the respect and admiration that he so richly deserves.

Selected Primary Writings

Thoughts on Government (1776)19

My dear Sir,—If I was equal to the task of forming a plan for the government of a colony, I should be flattered with your request, and very happy to comply with it; because, as the divine science of politics is the science of social happiness, and the blessings of society depend entirely on the constitutions of government, which are generally institutions that last for many generations, there can be no employment more agreeable to a benevolent mind than a research after the best.

Pope flattered tyrants too much when he said:

“For forms of government let fools contest,

That which is best administered is best.”

Nothing can be more fallacious than this. But poets read history to collect flowers, not fruits; they attend to fanciful images, not the effects of social institutions. Nothing is more certain, from the history of nations and nature of man, than that some forms of government are better fitted for being well administered than others.

We ought to consider what is the end of government, before we determine which is the best form. Upon this point all speculative politicians will agree, that the happiness of society is the end of government, as all divines and moral philosophers will agree that the happiness of the individual is the end of man. From this principle it will follow, that the form of government which communicates ease, comfort, security, or, in one word, happiness, to the greatest number of persons, and in the greatest degree, is the best.

All sober inquirers after truth, ancient and modern, pagan and Christian, have declared that the happiness of man, as well as his dignity, consists in virtue. Confucius, Zoroaster, Socrates, Mahomet, not to mention authorities really sacred, have agreed in this.

If there is a form of government, then, whose principle and foundation is virtue, will not every sober man acknowledge it better calculated to promote the general happiness than any other form?

Fear is the foundation of most governments; but it is so sordid and brutal a passion, and renders men in whose breasts it predominates so stupid and miserable, that Americans will not be likely to approve of any political institution which is founded on it.

Honor is truly sacred, but holds a lower rank in the scale of moral excellence than virtue. Indeed, the former is but a part of the latter, and consequently has not equal pretensions to support a frame of government productive of human happiness.

The foundation of every government is some principle or passion in the minds of the people. The noblest principles and most generous affections in our nature, then, have the fairest chance to support the noblest and most generous models of government.

A man must be indifferent to the sneers of modern Englishmen, to mention in their company the names of Sidney, Harrington, Locke, Milton, Nedham, Neville, Burnet, and Hoadly. No small fortitude is necessary to confess that one has read them. The wretched condition of this country, however, for ten or fifteen years past, has frequently reminded me of their principles and reasonings. They will convince any candid mind, that there is no good government but what is republican. That the only valuable part of the British constitution is so; because the very definition of a republic is “an empire of laws, and not of men.” That, as a republic is the best of governments, so that particular arrangement of the powers of society, or, in other words, that form of government which is best contrived to secure an impartial and exact execution of the laws, is the best of republics.

Of republics there is an inexhaustible variety, because the possible combinations of the powers of society are capable of innumerable variations.

As good government is an empire of laws, how shall your laws be made? In a large society, inhabiting an extensive country, it is impossible that the whole should assemble to make laws. The first necessary step, then, is to depute power from the many to a few of the most wise and good. But by what rules shall you choose your representatives? Agree upon the number and qualifications of persons who shall have the benefit of choosing, or annex this privilege to the inhabitants of a certain extent of ground.

The principal difficulty lies, and the greatest care should be employed, in constituting this representative assembly. It should be in miniature an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them. That it may be the interest of this assembly to do strict justice at all times, it should be an equal representation, or, in other words, equal interests among the people should have equal interests in it. Great care should be taken to effect this, and to prevent unfair, partial, and corrupt elections. Such regulations, however, may be better made in times of greater tranquillity than the present; and they will spring up themselves naturally, when all the powers of government come to be in the hands of the people’s friends. At present, it will be safest to proceed in all established modes, to which the people have been familiarized by habit.

A representation of the people in one assembly being obtained, a question arises, whether all the powers of government, legislative, executive, and judicial, shall be left in this body? I think a people cannot be long free, nor ever happy, whose government is in one assembly. My reasons for this opinion are as follow:—

- A single assembly is liable to all the vices, follies, and frailties of an individual; subject to fits of humor, starts of passion, flights of enthusiasm, partialities, or prejudice, and consequently productive of hasty results and absurd judgments. And all these errors ought to be corrected and defects supplied by some controlling power.

- A single assembly is apt to be avaricious, and in time will not scruple to exempt itself from burdens, which it will lay, without compunction, on its constituents.

- A single assembly is apt to grow ambitious, and after a time will not hesitate to vote itself perpetual. This was one fault of the Long Parliament; but more remarkably of Holland, whose assembly first voted themselves from annual to septennial, then for life, and after a course of years, that all vacancies happening by death or otherwise, should be filled by themselves, without any application to constituents at all.

- A representative assembly, although extremely well qualified, and absolutely necessary, as a branch of the legislative, is unfit to exercise the executive power, for want of two essential properties, secrecy and despatch.

- A representative assembly is still less qualified for the judicial power, because it is too numerous, too slow, and too little skilled in the laws.

- Because a single assembly, possessed of all the powers of government, would make arbitrary laws for their own interest, execute all laws arbitrarily for their own interest, and adjudge all controversies in their own favor.

But shall the whole power of legislation rest in one assembly? Most of the foregoing reasons apply equally to prove that the legislative power ought to be more complex; to which we may add, that if the legislative power is wholly in one assembly, and the executive in another, or in a single person, these two powers will oppose and encroach upon each other, until the contest shall end in war, and the whole power, legislative and executive, be usurped by the strongest.

The judicial power, in such case, could not mediate, or hold the balance between the two contending powers, because the legislative would undermine it. And this shows the necessity, too, of giving the executive power a negative upon the legislative, otherwise this will be continually encroaching upon that.

To avoid these dangers, let a distinct assembly be constituted, as a mediator between the two extreme branches of the legislature, that which represents the people, and that which is vested with the executive power.

Let the representative assembly then elect by ballot, from among themselves or their constituents, or both, a distinct assembly, which, for the sake of perspicuity, we will call a council. It may consist of any number you please, say twenty or thirty, and should have a free and independent exercise of its judgment, and consequently a negative voice in the legislature.

These two bodies, thus constituted, and made integral parts of the legislature, let them unite, and by joint ballot choose a governor, who, after being stripped of most of those badges of domination, called prerogatives, should have a free and independent exercise of his judgment, and be made also an integral part of the legislature. This, I know, is liable to objections; and, if you please, you may make him only president of the council, as in Connecticut. But as the governor is to be invested with the executive power, with consent of council, I think he ought to have a negative upon the legislative. If he is annually elective, as he ought to be, he will always have so much reverence and affection for the people, their representatives and counsellors, that, although you give him an independent exercise of his judgment, he will seldom use it in opposition to the two houses, except in cases the public utility of which would be conspicuous; and some such cases would happen.

In the present exigency of American affairs, when, by an act of Parliament, we are put out of the royal protection, and consequently discharged from our allegiance, and it has become necessary to assume government for our immediate security, the governor, lieutenant-governor, secretary, treasurer, commissary, attorney-general, should be chosen by joint ballot of both houses. And these and all other elections, especially of representatives and counsellors, should be annual, there not being in the whole circle of the sciences a maxim more infallible than this, “where annual elections end, there slavery begins.” . . .

This will teach them the great political virtues of humility, patience, and moderation, without which every man in power becomes a ravenous beast of prey.

This mode of constituting the great offices of state will answer very well for the present; but if by experiment it should be found inconvenient, the legislature may, at its leisure, devise other methods of creating them, by elections of the people at large . . . or it may enlarge the term for which they shall be chosen to seven years, or three years, or for life, or make any other alterations which the society shall find productive of its ease, its safety, its freedom, or, in one word, its happiness.

A rotation of all offices, as well as of representatives and counsellors, has many advocates, and is contended for with many plausible arguments. It would be attended, no doubt, with many advantages; and if the society has a sufficient number of suitable characters to supply the great number of vacancies which would be made by such a rotation, I can see no objection to it. These persons may be allowed to serve for three years, and then be excluded three years, or for any longer or shorter term.

Any seven or nine of the legislative council may be made a quorum, for doing business as a privy council, to advise the governor in the exercise of the executive branch of power, and in all acts of state.

The governor should have the command of the militia and of all your armies. The power of pardons should be with the governor and council.

Judges, justices, and all other officers, civil and military, should be nominated and appointed by the governor, with the advice and consent of council, unless you choose to have a government more popular; if you do, all officers, civil and military, may be chosen by joint ballot of both houses; or, in order to preserve the independence and importance of each house, by ballot of one house, concurred in by the other. Sheriffs should be chosen by the freeholders of counties; so should registers of deeds and clerks of counties.

All officers should have commissions, under the hand of the governor and seal of the colony.

The dignity and stability of government in all its branches, the morals of the people, and every blessing of society depend so much upon an upright and skilful administration of justice, that the judicial power ought to be distinct from both the legislative and executive, and independent upon both, that so it may be a check upon both, as both should be checks upon that. The judges, therefore, should be always men of learning and experience in the laws, of exemplary morals, great patience, calmness, coolness, and attention. Their minds should not be distracted with jarring interests; they should not be dependent upon any man, or body of men. To these ends, they should hold estates for life in their offices; or, in other words, their commissions should be during good behavior, and their salaries ascertained and established by law. For misbehavior, the grand inquest of the colony, the house of representatives, should impeach them before the governor and council, where they should have time and opportunity to make their defence; but, if convicted, should be removed from their offices, and subjected to such other punishment as shall be thought proper.

A militia law, requiring all men, or with very few exceptions besides cases of conscience, to be provided with arms and ammunition, to be trained at certain seasons; and requiring counties, towns, or other small districts, to be provided with public stocks of ammunition and intrenching utensils, and with some settled plans for transporting provisions after the militia, when marched to defend their country against sudden invasions; and requiring certain districts to be provided with field-pieces, companies of matrosses, and perhaps some regiments of light-horse, is always a wise institution, and, in the present circumstances of our country, indispensable.

Laws for the liberal education of youth, especially of the lower class of people, are so extremely wise and useful, that, to a humane and generous mind, no expense for this purpose would be thought extravagant.

The very mention of sumptuary laws will excite a smile. Whether our countrymen have wisdom and virtue enough to submit to them, I know not; but the happiness of the people might be greatly promoted by them, and a revenue saved sufficient to carry on this war forever. Frugality is a great revenue, besides curing us of vanities, levities, and fopperies, which are real antidotes to all great, manly, and warlike virtues.

…A constitution founded on these principles introduces knowledge among the people, and inspires them with a conscious dignity becoming freemen; a general emulation takes place, which causes good humor, sociability, good manners, and good morals to be general. That elevation of sentiment inspired by such a government, makes the common people brave and enterprising. That ambition which is inspired by it makes them sober, industrious, and frugal. You will find among them some elegance, perhaps, but more solidity; a little pleasure, but a great deal of business; some politeness, but more civility. If you compare such a country with the regions of domination, whether monarchical or aristocratical, you will fancy yourself in Arcadia or Elysium.

If the colonies should assume governments separately, they should be left entirely to their own choice of the forms; and if a continental constitution should be formed, it should be a congress, containing a fair and adequate representation of the colonies, and its authority should sacredly be confined to these cases, namely, war, trade, disputes between colony and colony, the post-office, and the unappropriated lands of the crown, as they used to be called. . . .

You and I, my dear friend, have been sent into life at a time when the greatest lawgivers of antiquity would have wished to live. How few of the human race have ever enjoyed an opportunity of making an election of government, more than of air, soil, or climate, for themselves or their children! When, before the present epocha, had three millions of people full power and a fair opportunity to form and establish the wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive? I hope you will avail yourself and your country of that extensive learning and indefatigable industry which you possess, to assist her in the formation of the happiest governments and the best character of a great people….

A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, Vol. 1 (1786–1787)20

The arts and sciences, in general, during the three or four last centuries, have had a regular course of progressive improvement. The inventions in mechanic arts, the discoveries in natural philosophy, navigation, and commerce, and the advancement of civilization and humanity, have occasioned changes in the condition of the world, and the human character, which would have astonished the most refined nations of antiquity. A continuation of similar exertions is every day rendering Europe more and more like one community, or single family. Even in the theory and practice of government, in all the simple monarchies, considerable improvements have been made. The checks and balances of republican governments have been in some degree adopted at the courts of princes. By the erection of various tribunals, to register the laws, and exercise the judicial power—by indulging the petitions and remonstrances of subjects, until by habit they are regarded as rights—a control has been established over ministers of state, and the royal councils, which, in some degree, approaches the spirit of republics. Property is generally secure, and personal liberty seldom invaded. The press has great influence, even where it is not expressly tolerated; and the public opinion must be respected by a minister, or his place becomes insecure. Commerce begins to thrive; and if religious toleration were established, personal liberty a little more protected, by giving an absolute right to demand a public trial in a certain reasonable time, and the states were invested with a few more privileges, or rather restored to some that have been taken away, these governments would be brought to as great a degree of perfection, they would approach as near to the character of governments of laws and not of men, as their nature will probably admit of. In so general a refinement, or more properly a reformation of manners and improvement in science, is it not unaccountable that the knowledge of the principles and construction of free governments, in which the happiness of life, and even the further progress of improvement in education and society, in knowledge and virtue, are so deeply interested, should have remained at a full stand for two or three thousand years?

…Representations, instead of collections, of the people; a total separation of the executive from the legislative power, and of the judicial from both; and a balance in the legislature, by three independent, equal branches, are perhaps the only three discoveries in the constitution of a free government, since the institution of Lycurgus. Even these have been so unfortunate, that they have never spread: the first has been given up by all the nations, excepting one, which had once adopted it; and the other two, reduced to practice, if not invented, by the English nation, have never been imitated by any other, except their own descendants in America.

While it would be rash to say, that nothing further can be done to bring a free government, in all its parts, still nearer to perfection, the representations of the people are most obviously susceptible of improvement. The end to be aimed at, in the formation of a representative assembly, seems to be the sense of the people, the public voice. The perfection of the portrait consists in its likeness. Numbers, or property, or both, should be the rule; and the proportions of electors and members an affair of calculation. The duration should not be so long that the deputy should have time to forget the opinions of his constituents. Corruption in elections is the great enemy of freedom…. We shall learn to prize the checks and balances of a free government, and even those of the modern aristocracies, if we recollect the miseries of Greece, which arose from its ignorance of them. The only balance attempted against the ancient kings was a body of nobles; and the consequences were perpetual alternations of rebellion and tyranny, and the butchery of thousands upon every revolution from one to the other. When kings were abolished, aristocracies tyrannized; and then no balance was attempted but between aristocracy and democracy. This, in the nature of things, could be no balance at all, and therefore the pendulum was forever on the swing.

…Such were the fashionable outrages of unbalanced parties. In the name of human and divine benevolence, is such a system as this to be recommended to Americans, in this age of the world? Human nature is as incapable now of going through revolutions with temper and sobriety, with patience and prudence, or without fury and madness, as it was among the Greeks so long ago…. Without three orders, and an effectual balance between them, in every American constitution, it must be destined to frequent unavoidable revolutions; though they are delayed a few years, they must come in time. The United States are large and populous nations, in comparison with the Grecian commonwealths, or even the Swiss cantons; and they are growing every day more disproportionate, and therefore less capable of being held together by simple governments. Countries that increase in population so rapidly as the States of America did, even during such an impoverishing and destructive war as the last was, are not to be long bound with silken threads; lions, young or old, will not be bound by cobwebs. It would be better for America, it is nevertheless agreed, to ring all the changes with the whole set of bells, and go through all the revolutions of the Grecian States, rather than establish an absolute monarchy among them, notwithstanding all the great and real improvements which have been made in that kind of government….

It is become a kind of fashion among writers, to admit, as a maxim, that if you could be always sure of a wise, active, and virtuous prince, monarchy would be the best of governments. But this is so far from being admissible, that it will forever remain true, that a free government has a great advantage over a simple monarchy. The best and wisest prince, by means of a freer communication with his people, and the greater opportunities to collect the best advice from the best of his subjects, would have an immense advantage in a free state over a monarchy. A senate consisting of all that is most noble, wealthy, and able in the nation, with a right to counsel the crown at all times, is a check to ministers, and a security against abuses, such as a body of nobles who never meet, and have no such right, can never supply. Another assembly, composed of representatives chosen by the people in all parts, gives free access to the whole nation, and communicates all its wants, knowledge, projects, and wishes to government; it excites emulation among all classes, removes complaints, redresses grievances, affords opportunities of exertion to genius, though in obscurity, and gives full scope to all the faculties of man; it opens a passage for every speculation to the legislature, to administration, and to the public; it gives a universal energy to the human character, in every part of the state, such as never can be obtained in a monarchy.

…There can be no free government without a democratical branch in the constitution…. The people in America have now the best opportunity and the greatest trust in their hands, that Providence ever committed to so small a number, since the transgression of the first pair; if they betray their trust, their guilt will merit even greater punishment than other nations have suffered, and the indignation of Heaven. If there is one certain truth to be collected from the history of all ages, it is this; that the people’s rights and liberties, and the democratical mixture in a constitution, can never be preserved without a strong executive, or, in other words, without separating the executive from the legislative power. If the executive power, or any considerable part of it, is left in the hands either of an aristocratical or a democratical assembly, it will corrupt the legislature as necessarily as rust corrupts iron, or as arsenic poisons the human body; and when the legislature is corrupted, the people are undone.

The rich, the well-born, and the able, acquire an influence among the people that will soon be too much for simple honesty and plain sense, in a house of representatives. The most illustrious of them must, therefore, be separated from the mass, and placed by themselves in a senate; this is, to all honest and useful intents, an ostracism. A member of a senate, of immense wealth, the most respected birth, and transcendent abilities, has no influence in the nation, in comparison of what he would have in a single representative assembly. When a senate exists, the most powerful man in the state may be safely admitted into the house of representatives, because the people have it in their power to remove him into the senate as soon as his influence becomes dangerous. The senate becomes the great object of ambition; and the richest and the most sagacious wish to merit an advancement to it by services to the public in the house. When he has obtained the object of his wishes, you may still hope for the benefits of his exertions, without dreading his passions; for the executive power being in other hands, he has lost much of his influence with the people, and can govern very few votes more than his own among the senators.

…The United States of America have exhibited, perhaps, the first example of governments erected on the simple principles of nature; and if men are now sufficiently enlightened to disabuse themselves of artifice, imposture, hypocrisy, and superstition, they will consider this event as an era in their history. Although the detail of the formation of the American governments is at present little known or regarded either in Europe or in America, it may hereafter become an object of curiosity. It will never be pretended that any persons employed in that service had interviews with the gods, or were in any degree under the inspiration of Heaven, more than those at work upon ships or houses, or laboring in merchandise or agriculture; it will forever be acknowledged that these governments were contrived merely by the use of reason and the senses, as Copley painted Chatham; West, Wolf; and Trumbull, Warren and Montgomery; as Dwight, Barlow, Trumbull, and Humphries composed their verse, and Belknap and Ramsay history; as Godfrey invented his quadrant, and Rittenhouse his planetarium; as Boylston practised inoculation, and Franklin electricity; as Paine exposed the mistakes of Raynal, and Jefferson those of Buffon, so unphilosophically borrowed from the despicable dreams of De Pau. Neither the people, nor their conventions, committees, or sub-committees, considered legislation in any other light than as ordinary arts and sciences, only more important. Called without expectation, and compelled without previous inclination, though undoubtedly at the best period of time, both for England and America, suddenly to erect new systems of laws for their future government, they adopted the method of a wise architect, in erecting a new palace for the residence of his sovereign. They determined to consult Vitruvius, Palladio, and all other writers of reputation in the art; to examine the most celebrated buildings, whether they remain entire or in ruins; to compare these with the principles of writers; and to inquire how far both the theories and models were founded in nature, or created by fancy; and when this was done, so far as their circumstances would allow, to adopt the advantages and reject the inconveniences of all. . . . Thirteen governments thus founded on the natural authority of the people alone, without a pretence of miracle or mystery, and which are destined to spread over the northern part of that whole quarter of the globe, are a great point gained in favor of the rights of mankind. The experiment is made, and has completely succeeded; it can no longer be called in question, whether authority in magistrates and obedience of citizens can be grounded on reason, morality, and the Christian religion, without the monkery of priests, or the knavery of politicians. As the writer was personally acquainted with most of the gentlemen in each of the states, who had the principal share in the first draughts, the following work was really written to lay before the public a specimen of that kind of reading and reasoning which produced the American constitutions.

…The systems of legislators are experiments made on human life and manners, society and government. Zoroaster, Confucius, Mithras, Odin, Thor, Mahomet, Lycurgus, Solon, Romulus, and a thousand others, may be compared to philosophers making experiments on the elements. Unhappily, political experiments cannot be made in a laboratory, nor determined in a few hours. The operation once begun, runs over whole quarters of the globe, and is not finished in many thousands of years. The experiment of Lycurgus lasted seven hundred years, but never spread beyond the limits of Laconia. The process of Solon expired in one century; that of Romulus lasted but two centuries and a half; but the Teutonic institutions, described by Cæsar and Tacitus, are the most memorable experiment, merely political, ever yet made in human affairs. They have spread all over Europe, and have lasted eighteen hundred years. They afford the strongest argument that can be imagined in support of the position assumed in these volumes. Nothing ought to have more weight with America, to determine her judgment against mixing the authority of the one, the few, and the many, confusedly in one assembly, than the wide-spread miseries and final slavery of almost all mankind, in consequence of such an ignorant policy in the ancient Germans. What is the ingredient which in England has preserved the democratical authority? The balance, and that only. The English have, in reality, blended together the feudal institutions with those of the Greeks and Romans, and out of all have made that noble composition, which avoids the inconveniences, and retains the advantages of both.

The institutions now made in America will not wholly wear out for thousands of years. It is of the last importance, then, that they should begin right. If they set out wrong, they will never be able to return, unless it be by accident, to the right path….

Recommended Readings

- Joseph J. Ellis, Passionate Sage: The Character and Legacy of John Adams (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1993).

- Jon Ferling, John Adams: A Life (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1992).

- James Grant, John Adams: Party of One (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005).

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001).

- Richard Ryerson, John Adams’s Republic: The One, the Few, and the Many (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

- C. Bradley Thompson, John Adams and the Spirit of Liberty (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998).

- Gordon S. Wood, Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (New York: Penguin Books, 2018).

Notes

[1] “Notes on a Conversation with Thomas Jefferson,” in The Papers of Daniel Webster: Correspondence, ed. Charles M. Wiltse (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for Dartmouth College, 1974), Vol. I, p. 375.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “From John Adams to Moses Gill, 10 June 1775,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0014 (accessed May 16, 2025); John Adams, Novanglus; or, A History of the Dispute with America, from Its Origin, in 1754, to the Present Time, in The Revolutionary Writings of John Adams, selected and with a foreword by C. Bradley Thompson (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2000), p. xii, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/592/0077_LFeBk.pdf (accessed May 16, 2025). Hereinafter Revolutionary Writings.

[4] “Notes on a Conversation with Thomas Jefferson,” Papers of Daniel Webster: Correspondence, Vol. I, p. 375.

[5] John Adams, The Life of John Adams, in The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Vol. I, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1856), p. 200, https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/adams-the-works-of-john-adams-vol-1-life-of-the-author (accessed May 16, 2025). Hereinafter Works.

[6] John Adams, Diary, with Passages from an Autobiography, in Works, Vol. II (1850), p. 22, htps://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/2100/Adams1431-02_Bk.pdf (accessed May 16, 2025).

[7] Ibid., p. 59.

[8] Ibid.

[9] John Adams, A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, in Revolutionary Writings, p. 56.

[10] Ibid., p. 34. Emphasis added.

[11] John Adams, “The Earl of Clarendon to William Pym,” No. II, January 20, 1766, in Revolutionary Writings, p. 50.

[12] John Adams, “Governor Winthrop to Governor Bradford,” in Revolutionary Writings, p. 63.

[13] John Adams, Novanglus, in Revolutionary Writings, p. 15.

[14] John Adams, Diary: With Passages from an Autobiography, in Works, Vol. II, p. 331.

[15] Ibid., p. 328.

[16] “Adams to Elbridge Gerry, 6 December 1777,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-05-02-0206 (accessed May 16, 2025).

[17] “John Adams to John Quincy Adams, May 16, 1815,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-03-02-2869 (accessed May 16, 2025).

[18] “July Fourth Toast by John Adams, June 30, 1826,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-8030 (accessed May 16, 2025).

[19] John Adams, “Thoughts on Government,” in Works, Vol. IV (1851), pp. 193–200, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/2102/Adams_1431-04_Bk.pdf (accessed May 16, 2025).

[20] Ibid., pp. 283–285, 287–294, 297–298.