Steven P. Bucci, PhD

In the post-9/11 period of war and subsequent military drawdown, Special Operations Forces (SOF) appear likely to grow in numbers, funding, and importance—but not necessarily in general understanding. One of the most flexible and useful instruments in America’s national security toolbox, SOF are regularly referred to incorrectly, incompletely, and with little depth of knowledge by policymakers.

SOF are neither a panacea nor an insignificant oddity. If utilized correctly, they bring great benefit to the nation; used poorly, their capabilities and sometimes their lives are wasted. How, then, should this nation think about these compelling and often mythologized warriors and their role in supporting America’s vital national interests?

During times of austerity, the government often looks for ways to get “more bang for the buck.”1 When this budgetary philosophy is applied to the military, SOF, with their reputation for doing great things with fewer troops and resources than large conventional forces, seem like a bargain. This vision of a “surgical” capability that is made up of mature, “hard” professionals who make the right choices at the right time and that avoids the need to deploy larger formations of citizen soldiers at great expense can be very compelling.

Given America’s current fiscal difficulties, there is a growing danger of overutilizing or misapplying SOF, but this is not to say that SOF should not be used. In fact, SOF can and should be a major enabler for other elements of power as well as a shaper of security conditions that can minimize the need for larger deployments of conventional military forces. Getting this balance right is the key challenge for the military and policymakers.

This essay will address numerous issues regarding Special Operations Forces while attempting to answer several questions, including:

- How SOF serve as a tool of U.S. military efforts,

- How SOF provide strategic warning and prepare the environment,

- How SOF enable hard power by providing conventional forces a “warm start” and create options not otherwise possible, and

- How SOF amplify the effectiveness of hard power by doing things like leveraging infrastructure and using their ability to exploit actions/successes.

Finally, this essay will review SOF’s potential as a bridging capability during this time of strained resources. SOF will be a key part of America’s ability to meet the challenges of an increasingly worrisome threat environment while its conventional forces are in decline. Although they are not a substitute for other capabilities in the U.S. military, SOF can mitigate risk by helping to set the operating environment in the most advantageous manner possible.

Special Operations: A Primer

The term “Special Operations Forces (SOF)” is the only correct generic term for the organizations being discussed. It includes certain designated units of all services and all capabilities. First and foremost, SOF are the men and women that make up the units. They are, for the most part, mature and highly trained. A typical special operator (regardless of service or specialty) is married with a family; averages 29–34 years old; has at least eight years on active duty in the general purpose forces (GPF); has some cultural and language training (most are masters of cross-cultural communication); has attended numerous advanced-skills schools; and has at least some college education, if not multiple degrees (this includes the enlisted ranks).2

SOF competently operate a great deal of highly advanced U.S military equipment and are also proficient with the equipment of other services and countries. They are valued for their out-of-the-box thinking, imagination, and initiative. SOF can and do operate with a small footprint and can survive and thrive with a very light support tail. These SOF are seen as the consummate military professionals and as such are “detached from Main Street” in ways that the 18–22- year-olds in the general-purpose forces are not.

The Department of Defense defines Special Operations (SO) as operations that:

Require unique modes of employment, tactical techniques, equipment, and training often conducted in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive environments and characterized by one or more of the following: time sensitive, clandestine, low visibility, conducted with and/or through indigenous forces, requiring regional expertise, and/or a high degree of risk.3

There are some who claim that conventional forces can and do handle tasks that SOF handle. Yet SOF are often entrusted to perform missions that exceed the authority given to conventional military units, such as operating in “politically sensitive environments” or executing tasks that require special legal authorities.

Organizational Structure

To appreciate how SOF are “special,” one must understand how these forces are organized and how they operate.

U.S. Special Operations Command. The parent command of all SOF is U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), which is headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida.4 Established in 1987, USSOCOM is responsible for manning, training, and equipping all SOF units. It does this in conjunction with the four services, which also provide the troops to the SOF units. Although not a service branch, USSOCOM has certain service-like responsibilities including the procurement of SOF-specific items as needed.

SOCOM has had some disagreements with the services over funding, authorities, and which units get assigned to USSOCOM; it also has sparred with the Geographic Combatant Commanders (GCCs) over the authority to direct SOF missions. Currently, USSOCOM enjoys the widest operational mandate it has ever had and is seen by both the services and the GCCs as a very positive contributor to national security. USSOCOM maintains manning, training, and equipping responsibilities for deployed forces through the Theater Special Operations Commands (TSOCs) that are under the operational control of each GCC. The GCCs operationally manage the TSOCs, but USSOCOM’s worldwide situational awareness allows them to synchronize operations across GCC boundaries.

There are five major subcomponents to USSOCOM: U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC); Navy Special Warfare Command (NSW); Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC); Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC); and Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC)—one for each service with an additional multiservice special mission command. Each of these organizations contributes something unique to the special operations community. They have different roles and tend to specialize in certain types of missions or areas of operation.

Direct vs. Indirect Approaches

SOF operations fall broadly into two categories: direct and indirect. The direct approach consists of SOF raids and other operations that directly target the enemy, such as an operation executed by Navy SEALs to free American and Danish aid workers held by Somali pirates.5 According to Admiral William H. McRaven, former Commander of SOCOM:

The direct approach is characterized by technologically-enabled small-unit precision lethality, focused intelligence, and interagency cooperation integrated on a digitally-networked battlefield…. Extreme in risk, precise in execution and able to deliver a high payoff, the impacts of the direct approach are immediate, visible to [the] public and have had tremendous effects on our enemies’ networks throughout the decade.6

Such missions are typically brief (even if planning for them can be extensive) and usually carry a higher potential for the use of weapons; to use a popular description, they tend to be more “kinetic.”

The indirect approach is characterized by long-term commitments of SOF to help enable and aid other nations to improve their own military forces and security. McRaven explains:

The indirect approach includes empowering host nation forces, providing appropriate assistance to humanitarian agencies, and engaging key populations. These long-term efforts increase partner capabilities to generate sufficient security and rule of law, address local needs, and advance ideas that discredit and defeat the appeal of violent extremism.7

While the direct approach is focused on addressing immediate situations such as disrupting terrorist operations, the indirect approach is longer-term and seeks to prevent threatening situations from arising or to defuse them with the lowest investment of U.S. assets. One of the main ways it does this is by equipping U.S. partners to address their own security challenges more effectively. This approach can also be a key to ending larger conflicts on favorable terms.

U.S. Army Special Operations Command. The U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) has its headquarters at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and is the largest component of USSOCOM (28,500 troops) with troops spread across the country and some overseas. It has six different types of units under its control: Special Forces, Rangers, Special Operations Aviation, Civil Affairs, Military Information Special Operations, and Special Operations Sustainment.8

U.S. Army Special Forces Command is the parent headquarters of all Special Forces (SF) soldiers, more commonly known as Green Berets.9 They have five active-duty groups. Each is traditionally oriented on a region, but this has been stretched by the wars of the past decade, which required all the SF units to rotate into the fight: Pacific (1st Group); Africa (3rd Group); the Middle East (5th Group); Latin America (7th Group); and Europe (10th Group, Fort Carson, Colorado).10 There are also two National Guard Groups (19th and 20th), which augment their active-duty counterparts.

SF units are generally older and more experienced than their fellow SOF. They are specialists in working with foreign militaries. Green Berets, for example, perform both direct missions and indirect tasks (discussed further below). They operate in 12-man teams, often remote in relation to other American forces.

The 75th Ranger Regiment is another element of USASOC. It is headquartered at Fort Benning, Georgia, and commands three battalions of what are considered the finest special light infantry troops in the world.11 While they are organized much as other light infantry units are organized, the Rangers’ level of training, readiness, and deployability exceeds that of their non-SOF counterparts. Although they are often used in small elements (squad, platoon, or company), the full weight of the Rangers is demonstrated when they perform battalion-level assaults and raids. They operate primarily as a direct action force.

The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) has a variety of highly modified rotary-wing platforms. They are stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and have three battalions organic to the regiment. Known as the Night Stalkers, they leverage not just their advanced and highly specialized equipment, but also their proficiency at operations conducted in the dark. Their aircraft (AH-6/MH-6 Little Birds, MH-60K/L/M Black Hawks, and MH-47 Chinooks) can be refueled in flight, have additional avionics and protective measures beyond the conventional models of these rotorcraft, and have added weaponry. The 160th delivers, provides fire support and supplies to, and (most important) exfiltrates other SOF elements under the most arduous conditions. Their ethos of leaving no one behind makes them a highly sought-after partner for any military operation.

The 95th Civil Affairs Brigade (CA), another resident of Fort Bragg, includes five battalions. Civil Affairs greatly expanded after it was realized in Afghanistan and Iraq that there was a greater need for active-duty units of this sort. There is a great deal of additional CA capability in the U.S. Army Reserve. These troops are specialists in operating with the civilian elements of another country’s government and economy with expertise ranging from airports to water systems. They can be deployed to assess the needs of a certain region pre-conflict, during combat operations, or post-conflict. They can also assist friendly elements in improving foreign civil structures. They support other SOF units but are regularly assigned to support conventional operations as well.

The 4th Military Information Support Group (MISG) is also stationed at Fort Bragg and has two subordinate MISG groups under its command.12 Formerly known as Psychological Operations, Military Information Special Operations (MISO) are highly versatile units that often use persuasive methods to convince targeted audiences to act in ways that are desirable to U.S. objectives. From tactical loudspeaker teams that might ask citizens to evacuate a town to strategic leaflet drops to inform an entire region that it would be beneficial to them to surrender, MISO units can be as powerful a weapon as any kinetic or lethal tool.

Also stationed at Fort Bragg, the 528th Sustainment Brigade has medical, logistics, and signal units that support not only Army SOF, but other elements of the U.S. military as well.13 These troops provide strategic abilities that deploy as often as their more combat-oriented fellow special operators. Two National Guard companies are aligned with the battalion in the 528th.

Naval Special Warfare Command. Naval Special Warfare Command (NSWC), headquartered at Coronado, California, is comprised of nearly 9,000 sailors.14 Its operational arms are the six Naval Special Warfare Groups. Each of these elements is organized differently and home-stationed on either the East or West Coast. They are made up of a combination of Sea, Air, Land (SEAL) operators, Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewmen, and Enablers.

The SEALs are one of the SOF’s best-known elements, renowned for their physical toughness and extremely exclusive selection process. Although clearly specialists at maritime-related operations, they perform operations far from water as well. If Army Special Forces are primarily indirect operators that can also perform direct action missions, SEALs are primarily direct operators who can also perform indirect training missions. Their specialty is small-unit commando actions and support for amphibious operations. As their name implies, they can be deployed through a multitude of means, including the SEAL Delivery Vehicle (a type of open mini-submarine).15

In the same way the SEALs often support the conventional Navy, the Navy often supports the SEALs, providing infiltration platforms such as attack submarines. The NSWC Combatant-craft Crewmen operate multiple vessels such as the MK V Special Operations Craft, the Special Operations Craft Riverine, and NSW Rigid-hull Inflatable Boat that deliver and recover the SEALs.16 The NSW Groups also utilize talented Enablers in communications, intelligence, and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) to augment SEAL operations.

Air Force Special Operations Command. Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC), stationed at Hurlburt Field, Florida, is probably the most diverse among the services’ SOF components. It has 18,000 members spread across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Under AFSOC’s command is the 23d Air Force, three active-duty Special Operations Wings, two Special Operations Groups, one Air Force Reserve Special Operations Wing, and one Air National Guard Special Operations Wing.17

One of AFSOC’s responsibilities is Pararescue, whose personnel are nicknamed “PJs.”18 These highly skilled operators are medical specialists qualified in multiple infiltration techniques to execute recovery operations. Their mission is “To rescue, recover, and return American or Allied forces in times of danger or extreme duress.”19

The Combat Controllers (CCT), another type of AFSOC personnel, are men who specialize in managing air assets from the ground.20 They can guide aerial bombardments or set up expedient airfields and act as the air traffic control tower. CCT include Special Operations Weathermen who habitually infiltrate into denied areas with other SOF elements to provide weather and intelligence support.

AFSOC also includes Combat Aviation Advisors.21 These are pilots and support personnel who work directly with foreign air forces as advisors and trainers. They train to become proficient in whatever systems and aircraft their allies operate. They must also be capable of political, cultural, and linguistic interaction with America’s foreign partners.

Finally, there are all of SOF’s aircrews. These teams operate numerous fixed-wing (such as AC-130H/U gunships, MC-130E/H infil/exfil, EC-130J MISO platform, MC-130P refueler, and MC-130J and MC-130W multipurpose) and tiltrotor-wing (CV-22B Osprey) aircraft. Powerful and versatile, these aircraft are the long-range lifeline of SOF.

Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command. Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC) is the newest of SOF’s service components. Established in 2006, MARSOC recognizes the growing need to provide additional numbers of highly skilled operators who can both teach and train allied foreign military forces while maintaining proficiency in direct action missions. Its mission is “to be America’s force of choice to provide small lethal expeditionary teams for global special operations.”22

While numbering only 2,600, these Marines filled a critical gap and have become an essential part of the special operations community. Headquartered at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, the Command oversees the Marine Special Operations Regiment with three battalions of Critical Skills Operators. They also command an SO Support Group, an SO Intelligence Battalion, and the Marine SO School.

Joint Special Operations Command. Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) is the final component of USSOCOM and is headquartered at Fort Bragg.23 This organization’s primary responsibility is to act as a special test and evaluation element for advanced SOF equipment and techniques.24

JSOC also includes a highly classified unit at the joint headquarters for America’s Tier One Countering Terrorism (CT) Special Mission Units (SMU). They have assigned elements from the other components, notably SEAL Team 6 and 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta. JSOC also has other support (intelligence and communications) units and maintains close relationships with various units from all of the other Commands. The missions given to JSOC are regularly clandestine and are not attributed to its elements.

SOF Operational Methodologies and Ethos: The “SOF Truths”

There is insufficient space here for an in-depth review of the entire history and experience of each element in SOF. It is possible, however, to provide a broad outline of SOF operations.

As noted, all missions assigned to SOF can be categorized as either direct or indirect. Direct missions are executed by the U.S. SOF units themselves, normally unilaterally, and are designed to have a specified result within a well-defined period of time, usually of very short duration. Indirect missions are executed by working with other elements (usually foreign forces aligned with the U.S.) and tend to have longer time horizons.

Each of the various SOF elements focuses closely on some missions while maintaining the ability to perform all others. Specifically:

- U.S. Army Special Forces: Primarily indirect actions; habitually operate in small groups; can also perform direct missions.

- SEALs: Primarily direct actions; operate in small groups, near the water (but also operate on land and at sea as their name indicates); can also perform indirect training missions.

- Rangers: Primarily direct, large-scale operations; can perform smaller operations.

- Marine Critical Skill Operators: Primarily indirect; still maintain capability to perform direct missions.

- Military Information Special Operations: Indirect; can support direct actions of other units (either SOF or General Purpose).

- Civil Affairs: Indirect; can support direct actions of other units (either SOF or General Purpose).

- Air Force Aviation Advisors: Indirect.

- Combat Controllers, Pararescue, Special Operations Weathermen: Direct or indirect; can support any function as well as all missions.

There is, however, another way to encapsulate the approach to their missions that all SOF share. Referred to as “SOF Truths,” the following maxims apply across SOF and help to explain the mindset and ethos of special operators. They are a constant reminder to all members of SOF as to what comprises their professional foundation and what should inform decisions on the use of SOF.25

- SOF Truth #1: Humans are more important than hardware. People—not equipment—make the critical difference in the success or failure of a mission. The right people, highly trained and working as a team, will accomplish the mission with the equipment available. On the other hand, the best equipment in the world cannot compensate for a lack of the right people.

- SOF Truth #2: Quality is better than quantity. A small number of people, carefully selected, well-trained, and well-led, is preferable to larger numbers of troops, some of whom may not be up to the task.

- SOF Truth #3: Special Operations Forces cannot be mass produced. It takes years to train operational units to the level of proficiency needed to accomplish difficult and specialized SOF missions. Intense training, both in SOF schools and in units, is required to integrate competent individuals into fully capable units. This process cannot be hastened without degrading ultimate capability.

- SOF Truth #4: Competent Special Operations Forces cannot be created after emergencies occur. Creation of competent, fully mission-capable units takes time. Employment of fully capable special operations capability on short notice requires highly trained and constantly available SOF units in peacetime.

- SOF Truth #5: Most special operations require non-SOF assistance. The operational effectiveness of deployed forces cannot be, and never has been, achieved without being enabled by all the joint service partners. The Air Force, Army, Marine and Navy engineers, technicians, intelligence analysts, and numerous other professions that contribute to SOF have substantially increased SOF capabilities and effectiveness throughout the world.

These are not mere slogans; they are the principles by which SOF view themselves, their missions, and their world. Taking a moment to digest these ideals is worth the time and will allow for a higher degree of understanding of the men and women who make up USSOCOM. These five truths offer key insights into America’s Special Forces, such as:

- SOF are precious assets that take time, effort, and investment to develop;

- They are not suitable for “big-scale” tasks;

- Suddenly deciding to “make more” of them is a foolish and irresponsible goal; and

- SOF recognize that they are a small part of America’s military strength, not a replacement for any other part of the military.

Policymakers who consider employing SOF operationally must understand these facts lest they gamble with one of America’s most precious assets.

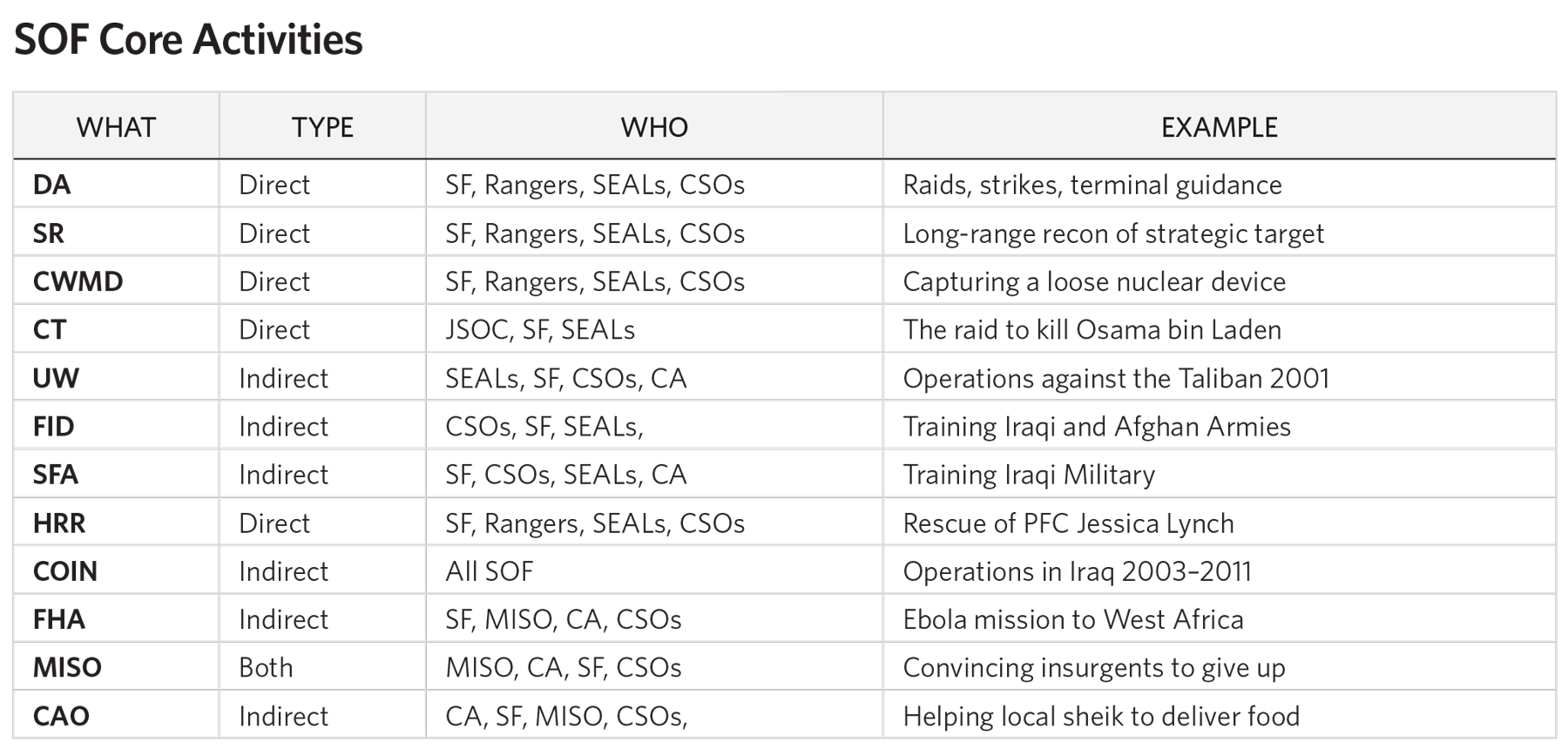

SOF Core Activities

According to the Department of Defense, “USSOCOM organizes, trains, and equips SOF for special operations core activities … and other such activities as may be specified by the President and/or SecDef. These core activities reflect the collective capabilities of all joint SOF rather than those of any one Service or unit.”26 The activities enumerated by SOCOM are:27

- Direct Action (DA). Short-duration strikes in hostile, denied, or diplomatically sensitive environments to seize, destroy, capture, exploit, recover, or damage designated targets.

- Special Reconnaissance (SR). Reconnaissance and surveillance normally conducted in a clandestine or covert manner to collect or verify information of strategic or operational significance, employing military capabilities not normally found in conventional forces.

- Countering WMD Operations (CWMD). Support provided to GCCs through technical expertise, matériel, and special teams to locate, tag, and track WMD and/or conduct DA to prevent use of WMD or to assist in its neutralization or recovery.

- Counterterrorism (CT). Actions taken under conditions not conducive to the use of conventional forces to neutralize terrorists and their networks in order to render them incapable of using unlawful violence.

- Unconventional Warfare (UW). Actions taken to enable an indigenous resistance movement to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power.

- Foreign Internal Defense (FID). Activities that support a country’s internal defense program designed to protect against subversion, lawlessness, insurgency, terrorism, and other threats to the country’s internal security and stability.

- Security Force Assistance (SFA). Activities that contribute to a broad effort by the U.S. government to support the development of the capacity and capability of foreign security forces and their supporting institutions.

- Hostage Rescue and Recovery (HRR). Sensitive crisis response missions in response to terrorist threats and incidents where SOF support the rescue of hostages or the recapture of U.S. facilities, installations, and sensitive material overseas.

- Counterinsurgency (COIN). SOF support to a comprehensive civilian and military effort to contain and ultimately defeat an insurgency and address its root causes. SOF are particularly adept at using an indirect approach to positively influence segments of the indigenous population.

- Foreign Humanitarian Assistance (FHA). SOF support to a range of DOD humanitarian activities conducted outside the U.S. and its territories to relieve or reduce human suffering, disease, hunger, or privation. SOF can rapidly deploy with excellent long-range communications equipment, and they are able to operate in the austere and often chaotic environments typically associated with disaster-related HA efforts. Perhaps the most important capabilities found within SOF for FHA are their geographic orientation, cultural knowledge, language capabilities, and ability to work with multiethnic indigenous populations and international relief organizations to provide initial and ongoing assessments.

- Military Information Support Operations (MISO). MISO are planned to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence their emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behavior of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals in a manner favorable to the originator’s objectives.

- Civil Affairs Operations (CAO). CAO are actions that enhance the operational environment, identify and mitigate underlying causes of instability within civil society, or involve the application of functional specialty skills that are normally the responsibility of civil government.

The varying nature of these activities tends to differentiate between direct and indirect. Furthermore, certain SOF components are more prone to undertake some types of activities over others, although all SOF can be called upon to execute any of these activities if the situation demands. It should be noted that all of the direct missions and some of the indirect missions could and in all likelihood would require support from Army or Air Force aviation assets or NSW craft, as well as PJs, CCTs, and SO Weathermen.

As described, the responsibilities and capabilities of SOF are broad and comprehensive. They play many roles and perform them all with an extremely high level of proficiency. These missions can be simple and tactical, or they can be highly complex and have extremely critical strategic effects. One important thing to note is that SOF never think that they conduct Major Combat Operations alone. This is not humility; it is simple recognition that SOF have their limitations.

How SOF Enables Military Capabilities

SOF are not a panacea for all of this nation’s military challenges. However, when used correctly in conjunction with the rest of the American military in support of U.S. national security objectives, SOF can help to make a difference in achieving strategic objectives.

To illustrate this point, it is helpful to overlay SOF’s direct and indirect capabilities across the phases of a major military operation:

- Phase 0: Shape the situation in the target country (or theater).

- Phase I: Deter the adversary from taking any adverse actions.

- Phase II: Seize the initiative before the adversary can do so.

- Phase III: Dominate the enemy.

- Phase IV: Stabilize the situation.

- Phase V: Enable the friendly civil authorities.

- Phase 0: Return to shaping the situation.

Within each phase, SOF have a role to play that creates conditions for success and amplifies the effects of other elements of national power. For example:

- Phase 0 (Shape)

- Type of Action: Indirect.

- SOF Activities: Information and intelligence gathering; building relationships; conducting training; on-the-ground familiarization; keeping the friendly elements functioning.

- Example of Mission: A rotating training mission conducted on a fairly continuous basis in Kuwait. A small SF training team would provide year-round instruction, tailoring their actions to the specific needs of the Kuwaitis. They also get to know all of the leaders of the units with whom they work.

- Phase I (Deter)

- Type of Action: Primarily indirect.

- SOF Activities: Advising local security forces; helping to eliminate threats to the friendly regime through more direct intelligence support.

- Example of Mission: The forces sent to Mali before the larger intervention by the French as they fought forces backed by al-Qaeda.

- Phases II–IV (Seize, Dominate, and Stabilize)

- Type of Activity: Direct and indirect.

- SOF Activities: Long-range reconnaissance; terminal guidance; deep precision strikes; advisory role with local military; advisory role with coalition partners; advisory role with local civil defense forces; CT hunting; raids; cutting supply lines.

- Example of Mission: In these active combat phases, SOF are often subordinated to conventional forces in the theater and attacks targets at their direction, providing special reconnaissance before conventional attacks. These forces can also be sent after strategic targets such as the elimination or capture of high-value personnel. They can also provide liaison officers to help overcome allied communications difficulties or to aid in managing supporting assets such as close air support.

- Phase V (Enable)

- Type of Activity: Primarily indirect with some isolated direct activities.

- SOF Activities: Continue advisory role; continue gathering intel; bridge the time between the departure of U.S.–Coalition forces and the stepping-up of local capabilities; monitor final resolution of enemy forces or demobilization process.

- Example of Mission: In this phase, SOF can be the key to a smooth turnover of responsibility to the local authorities and departure of American GPF. This was done in Iraq in 2011 as SOF were the last units to leave—an effort to ensure that the Iraqis had the best possible chance of success when the Americans returned home.

- Phase 0 (Shape)

- Type of Activity: Indirect.

- SOF Activities: Return to information and intelligence gathering, the building of relationships and networks, training, on-the-ground familiarization, keeping the friendly elements functioning.

- Example of Mission: A small SF training team would provide year-round instruction, tailoring their actions to the specific needs of the Kuwaitis.

As described, SOF are involved across the spectrum of operations from peacetime to conflict to war and back again. The relationships and intelligence that these operators gain in the pre-conflict Phase 0 are critical in maintaining awareness and supporting stabilizing agents in areas of conflict or interest. If a scenario moves to Phase I, SOF members can act as an early deterrent force, sometimes with their own actions but more than likely by facilitating a local force’s ability to operate more effectively. During Phases II–IV, their direct activities will support conventional general-purpose forces operations, and their indirect ones can keep the host force (be it a resistance force or government forces) in the fight.

The indirect operations of SOF become even more evident in Phase V as U.S. forces try to set the conditions for the general-purpose forces to depart once local authorities no longer need assistance. From there, SOF can stay in smaller pre-conflict numbers to return to their indirect activities and shaping functions.

While SOF may be known publicly more for direct operations such as the bin Laden strike, the indirect shaping activities are arguably more important to long-term U.S. interests and can save a great many lives and assets. As noted, SOF provide strategic warning and, if necessary, prepare the environment for general-purpose forces. SOF enable hard power by providing conventional forces with a “warm start” and can provide options not otherwise possible. Finally, SOF amplify the effectiveness of hard power by doing things like in situ targeting, leveraging of infrastructure, and using their ability to exploit actions based on detailed local knowledge and relationships.

SOF’s Abilities to Execute Missions Effectively

On any given day, U.S. Special Operations Forces are operating in about 75 different countries, mostly in non-combat operations.28 Due to the nature of the many dispersed threats facing the U.S. today, SOF’s unique capabilities are also in higher demand than at any other point in their history.29

Assessing the readiness of SOF involves six key questions:

- Do SOF have the appropriate doctrine: Are the missions the right ones?

- Does USSOCOM have the correct numbers of forces: Are they adequately sized?

- Do SOF have the appropriate diversity of personnel: Is the force mix right?

- Do SOF have the best equipment to do the job: Are the platforms and equipment what are really needed?

- Are all forces appropriately trained and experienced: Do the personnel have the right skills, abilities, and experience?

- Does USSOCOM have the correct authorities: Can SOF legally perform actions required of them?

SOF Doctrine. The SOF doctrine is comprehensive and appropriate. It provides for maximum coverage of the various tasks that SOF are called to execute. Units that can perform the Core SO Activities effectively within the Core SO Operations are provided the tools to complete their tasks.

In the early years of SOF, the doctrine was a mix of different approaches, standards, definitions, and perspectives. USSOCOM’s efforts to reconcile variations has provided a common direction, has established uniformity as and where necessary, and allows the commanders and planners to know what the troops theoretically are capable of doing while giving unit operators exactly the guidance they need to develop their training regimes. Additionally, the doctrine is tied to the wider Defense Department Joint Doctrine in a way that maximizes the ability to leverage SOF to enable the General Purpose Forces (GPF) and to achieve the best support from the GPF for SOF operations.30

Size of USSOCOM. SOF has grown significantly since 9/11, but is that growth enough?31 To make such a determination, one needs to discuss the broader U.S. military reductions that are taking place.32 While reducing the number of conventional ground forces overall—and specifically in the Middle East—is current U.S. policy, such cuts do not make for sound defense policy and, in fact, harm the ability of SOF to do their job in two key ways:

- Since SOF depend so heavily on conventional forces for organic combat support and combat service support,33 the drawdown of Army and Marine Corps end strength “brings up concerns the services might be hard-pressed to establish and dedicate enabling units needed by USSOCOM while at the same time adequately supporting general purpose forces.”34

- Because SOCOM draws its operators and support staff from the various services, a decrease in the size of the conventional force subsequently decreases the recruiting pool on which SOCOM relies for quality personnel.35

With the coming drawdown in Army and Marine end strength but no apparent reduction in the requirements generated by U.S. global strategy, SOF will likely see an increase in operational tempo. The current force is about 67,000 personnel, a figure slated to increase to 70,000 over the next several years, of which around 12,000 can be deployed at any given time.36 However, the strict requirements for entry into the SOF and the emphasis on retaining a top-tier fighting force limit the growth rate for SOF expansion. The maximum growth rate per year without sacrificing quality is about a 3 percent to 5 percent increase in personnel.37

Combined with the greater use of SOF, this low growth rate will put additional pressure on an already stretched force. As Mackenzie Eaglen, defense expert at the American Enterprise Institute, points out:

While some in Congress have been concerned about the readiness of the U.S. military and troops on their fifth or sixth combat tour, many special forces operators have already served 10 or more overseas combat tours. That pace is unsustainable with even marginal growth of SOF.38

One can conclude that despite the growth of SOF (both current and planned), they are probably only marginally at an appropriate size for the present and coming missions. This is a concern because the pressure on SOF to pick up a greater share of duties will be strong. The questions of force size and quality relative to operational demand must be monitored closely.

SOF Diversity of Force Capabilities. There must be sufficient redundancy to meet surge requirements and unforeseen challenges. Events in multiple parts of the world cannot necessarily be dealt with sequentially and often require simultaneous actions. No individual service component has enough forces to ensure that no gaps will ever develop, but as a whole, USSOCOM appears—at present—to have ample diversity to cover its global responsibilities.

The direct and indirect capabilities construct is a useful guide, as the various forces can move between the two methodologies with enough skill to address various challenges. For instance, SEALs are able to fight deep in mountainous terrain, Army Special Forces can execute SCUBA insertions from submarines, and Marine CSOs can train indigenous forces or perform a raid—all examples of this critically important redundancy. Army SOA can deliver SOF personnel from any service on a counterterrorist strike and then operate alongside Air Force CV-22 Ospreys to deliver supplies to a CA team in an urban area.

The bottom line is that the force mixture gives America a great deal of resilience. If troops are lost or needed elsewhere, USSOCOM has multiple options to replace them with forces from multiple sources. Such diversity of force capabilities is one of SOF’s greatest strengths.

SOF Equipment. The units in SOF are more about the people than gear, but operators need specialized tools to perform their specialized tasks; in fact, it is the effective pairing of highly developed skills and the right equipment that enables SOF to do what they do. For the most part, SOF have received the equipment they deem necessary. Their fixed-wing, rotary-wing, and tiltrotor aircraft are typically substantially upgraded versions of GPF models.39 Certain units in SOF have commercially available “add-ons” to weapons and communications gear, but for the most part, SOF carry many of the same items as their conventional counterparts. There is, however, a constant struggle to ensure that they continue to be properly equipped.

USSOCOM has its own acquisition authority (Major Force Program 11) that allows the command to buy items outside of the normal service channels’ acquisition processes.40 While the services are currently excellent at providing for the needs of their component units, if budget reduction trends continue, this support may become problematic, and MFP 11 can help SOF to sustain their ability to provide for their own specialized equipment needs. SOF are therefore adequate in this measurement.

SOF Training and Experience. SOF personnel are experienced and well-trained. The youngest personnel in SOF enter with extensive GPF experience, while the more mature members in some cases have been deployed in combat nearly constantly for more than a decade. It is possible that SOF are the most combat-experienced command in U.S. history.

Yet there is one area in which SOF, due to the high operational tempo in combat operations, lack experience: indirect actions. Army SF personnel in particular (but also some Navy SEALs and parts of AFSOF) have not undertaken indirect activities for years. This presents a potential training challenge for SOF, although a correction may already be underway. Former USSOCOM Commander Admiral William McRaven began working to shift the command from a nearly single-minded focus on counterterrorist, direct action operations back to the critical Phase 0 indirect activities that were not prioritized while the operators fought al-Qaeda in Iraq and Afghanistan (with the exception of some indirect training missions performed in both of those countries).

The current USSOCOM Commander, Army General Joseph L. Votel, appears ready to continue Admiral McRaven’s plans for a global SOF network that would connect America’s special operators with like-minded units from around the world both to improve and to leverage their capabilities.41 Such a network represents classic indirect operational focus; it is safe to assume that in short order, USSOCOM will make up for any training deficiency in its indirect skill set.

In the future, if USSOCOM has its training budget cut in a manner similar to what many GPF are facing, their ability to maintain their absolutely necessary high levels of readiness will be jeopardized. For now, however, this does not seem to be an immediate possibility. That said, any budget cuts must be monitored closely for the simple reason that SOF operators’ unparalleled effectiveness derives primarily from the fact that they shoot more, fly more, and conduct realistic exercises more than any other units in history. Lose that edge, and SOF will lose one of the important characteristics that make them so special.

SOF Authorities Under Which USSOCOM Operates. SOF have largely received the legal authority necessary for them to perform their missions. Under Admiral McRaven, USSOCOM was able to secure expanded authority for SOF operations within the GCC Theaters and receive a consensus approval from the senior military commanders and service chiefs to do so.42 Admiral McRaven also expanded the command’s presence in Washington and across the federal interagency system. USSOCOM now has the ability to synchronize SOF operations around the world, and it does this without overstepping the authorities of the Geographic Combatant Commanders or U.S. ambassadors who represent the U.S. in their respective countries.43

Conclusion

Given SOF’s relatively solid posture and future, as well as their ability to execute subtle yet critical indirect activities, they may be the most advantageous force choice for the difficult period America is entering. Between the lack of appetite in both American government and the public for large-scale force deployments, as well as the fiscal difficulties facing the GPFs, SOF will likely be required to assume increasing amounts of responsibility.

It is hoped that lawmakers will reverse the U.S. military’s decline. Until that time, however, policymakers might be tempted to consider SOF as an alternative way to boost military capacity in the immediate future. The indirect activities performed by USSOCOM will likely be called upon increasingly to provide for the protection of American interests or at least to mitigate the threats to those interests.

In that spirit, the following should be understood about Special Operations Forces:

- There are different types of SOF that have different purposes, values, and skills.

- The health and effectiveness of SOF are tightly linked to the professional health of the conventional forces: One cannot be substituted for the other.

- The nature of SOF and the missions they perform enables the U.S. to engage with the world in ways and to an extent not possible with conventional forces alone.

- Understanding how to use SOF properly preserves conventional force capabilities and capacities.

SOF can prepare areas where the U.S. anticipates that military operations might be necessary, is already conducting operations, or is trying to avoid becoming more involved in a given conflict or operation. Properly used, SOF can preclude problems altogether, reduce the size of conflicts if greater force is deemed necessary, amplify the effectiveness of conventional forces, establish relationships with indigenous forces of both state and non-state actors, provide precise targeting, and give high-resolution awareness that maximizes the likelihood of operational success. They can do all of this with a small footprint and while avoiding unintended or undesired damage.

SOF will be a key part of any bridge strategy as America manages a declining military structure in the midst of a growing threat environment. They can help to set the operating environment in the most advantageous manner possible. They are not, however, a replacement for conventional capabilities.

Indeed, there are numerous missions that SOF cannot perform: They cannot fight pitched battles with heavy forces; they cannot execute naval power projection; they cannot deploy strategic nuclear weapons. Furthermore, without an adequate recruitment base, SOF are hard to sustain, and without adequate conventional support, it becomes more difficult either to deploy SOF or to provide them with adequate support. When used correctly, however, SOF are extraordinarily valuable, even irreplaceable, in advancing U.S. security interests.

Such proficiency does come with a cost, as SOF are an expensive asset when compared “man to man” with conventional forces—and wasteful to taxpayers if they are misused. Policymakers must therefore strike an important balance: correctly deciding where, when, and for what purpose SOF should be deployed. There is simply no substitute for a strong and capable conventional ground force, but the same is true for SOF. Yet these units are not interchangeable, and it is unwise to place additional stress on SOF by expecting them to take on tasks for which they are not intended.

Endnotes

- Today’s austerity is in the form of the Budget Control Act of 2011 and subsequent “sequester” automatic cuts.

- United States Special Operations Command, U.S. Special Operations Command Fact Book 2013, p. 55, http://www.socom.mil/News/Documents/USSOCOM_Fact_Book_2013.pdf (accessed September 10, 2014).

- U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Special Operations, Joint Publication 03-05, July 16, 2014, p. ix, http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_05.pdf (accessed September 10, 2014).

- United States Special Operations Command, “About USSOC,” http://www.socom.mil/Pages/AboutUSSOCOM.aspx (accessed September 27, 2014).

- Jeffrey Gettleman, Eric Schmidt, and Thom Shanker, “U.S. Swoops in to Free 2 from Pirates in Somali Raid,” The New York Times, January 25, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/26/world/africa/us-raid-frees-2-hostages-from-somali-pirates.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all (accessed September 28, 2014).

- Admiral William H. McRaven, USN, Commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, posture statement before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, 112th Cong., March 6, 2012, http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/2012_hr/030612mcraven.pdf (accessed September 28, 2014).

- Ibid.

- United States Army Special Operations Command, “USASOC Headquarters Fact Sheet,” http://www.soc.mil/USASOCHQ/USASOCHQFactSheet.html (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Ibid.

- American Special Ops, “Special Forces,” http://www.americanspecialops.com/special-forces/ (accessed September 16, 2014).

- United States Army Special Operations Command, “75th Ranger Regiment,” http://www.soc.mil/Rangers/75thRR.html (accessed September 29, 2014).

- United States Army Special Operations Command, “4th Military Information Support Group,” http://www.soc.mil/4th%20MISG/4thMISG.html (accessed September 29, 2014).

- United States Army Special Operations Command, “528th Sustainment Brigade, Special Operations (Airborne),” http://www.soc.mil/528th/528th.html (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Naval Special Warfare Command, “Mission,” http://www.public.navy.mil/nsw/Pages/default.aspx (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Navy SEAL Museum, “SEAL Delivery Vehicles Manned Combatant Submersibles for Maritime Special Operations,” https://www.navysealmuseum.org/home-to-artifacts-from-the-secret-world-of-naval-special-warfare/seal-delivery-vehicles-sdv-manned-submersibles-for-special-operations (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Lee Ann Obringer, “How the Navy SEALS Work,” How Stuff Works, http://science.howstuffworks.com/navy-seal14.htm (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Air Force Special Operations Command, “Fact Sheet Alphabetical List,” http://www.afsoc.af.mil/AboutUs/FactSheets.aspx (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Air Force Special Operations Command, “Pararescue,” August 12, 2014, http://www.afsoc.af.mil/AboutUs/FactSheets/Display/tabid/140/Article/494098/pararescue.aspx (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Ibid.

- Air Force Special Operations Command, “Combat Controllers,” August 12, 2014, http://www.afsoc.af.mil/AboutUs/FactSheets/Display/tabid/140/Article/494096/combat-controllers.aspx (accessed September 29, 2014).

- SOFREP (Special Operations Forces Report), “Combat Aviation Advisors: A Day in the Life,” http://sofrep.com/combat-aviation-advisors/a-day-in-the-life/ (accessed September 29, 2014).

- U.S. Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command, “About,” http://www.marsoc.com/mission-vision/ (accessed September 16, 2014).

- GlobalSecurity.org, “Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC),” http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/dod/jsoc.htm (accessed September 29, 2014).

- United States Special Operations Command, “Joint Special Operations Command,” http://www.socom.mil/Pages/JointSpecialOperationsCommand.aspx (accessed September 29, 2014).

- United States Army Special Operations Command, “SOF Truths,” http://www.soc.mil/USASOCHQ/SOFTruths.html (accessed September 29, 2014).

- U.S. Department of Defense, Special Operations, p. II-2.

- These activities and their summarized or restated descriptions are taken from ibid., pp. II-1 to II-18.

- Jim Garamone, “Special Ops, Conventional Forces Work Together, Admiral Says,” American Forces Press Service, February 7, 2012, http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=67097 (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Robert Martinage, “Special Operations Forces: Future Challenges and Opportunities,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2008, http://www.csbaonline.org/publications/2008/11/special-operation-forces-future-challenges-and-opportunities/ (accessed September 29, 2014).

- U.S. Department of Defense, Special Operations.

- Hearing, The Future of U.S. Special Forces: Ten Years After 9/11 and Twenty-Five Years After Goldwater–Nichols, Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, 112th Cong., 2nd. Sess., September 22, 2011, http://fas.org/irp/congress/2011_hr/sof-future.pdf (accessed September 29, 2014).

- For a comprehensive overview of U.S. military capacity and capability across the services, see the “Capabilities” section of this report.

- Michael D. Lumpkin, Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low-Intensity Conflict, “The Future of U.S. Special Operations Forces: Ten Years After 9/11 and Twenty-Five Years After Goldwater–Nichols,” statement in hearing, The Future of U.S. Special Operations Forces: Ten Years After 9/11 and Twenty-Five Years After Goldwater–Nichols.

- Andrew Feickert, “U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF): Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, June 26, 2012, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS21048.pdf (accessed July 22, 2012).

- Ibid.

- Marcus Weisgerber, “Spec Ops to Grow as Pentagon Budget Shrinks,” Army Times, February 7, 2012, http://www.armytimes.com/news/2012/02/defense-spec-ops-to-grow-as-pentagon-budget-shrinks-020812/ (accessed September, 29, 2014).

- McRaven, posture statement before Senate Committee on Armed Services.

- Mackenzie Eaglen, “What’s Likely in New Pentagon Strategy: 2 Theaters, Fewer Bases, A2AD,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, December 20, 2011, http://www.heritage.org/research/commentary/2011/12/whats-likely-in-new-pentagon-strategy-2-theaters-fewer-bases-a2ad.

- American Special Ops, “Special Operations Aircraft,” http://www.americanspecialops.com/aircraft/ (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Defense Acquisition University, “Glossary of Defense Acquisition Acronyms and Terms,” https://dap.dau.mil/glossary/pages/2192.aspx (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Claudette Roulo, “Votel Takes Charge of Special Operations Command,” U.S. Department of Defense, http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=123032 (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Donna Miles, “New Authority Supports Global Special Operations Network,” U.S. Department of Defense, http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=120044 (accessed September 29, 2014).

- Matthew C. Weed and Nina M. Serafino, “U.S. Diplomatic Missions: Background and Issues on Chief of Mission (COM) Authority,” Congressional Research Service, March 10, 2014, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=751906 (accessed September 29, 2014).