In 2013, Heather Kokesch Del Castillo found herself in an unfulfilling career and began to question whether she was following her true passion. At the same time, she was growing increasingly dissatisfied with her physical fitness. She joined a local gym to make fitness a priority again.

That choice changed her life. Heather soon felt better than ever. And through her gym, she developed a network of supportive friends who introduced her to new ways of thinking about exercise, health, and nutrition.

Energized to pursue a new direction, Heather left her stagnating career to enroll in the Institute for Integrative Nutrition, a New York City-based school that specializes in training holistic health and wellness coaches. After a year of studying, Heather graduated as a privately certified health coach. Soon after, she founded her company, Constitution Nutrition, in Monterey, Calif.

At first, most of Heather’s clients were local. For many, the results were life-changing. Satisfied customers sang Heather’s praises with five-star reviews on internet ratings sites like Yelp, and many others told friends and family about their positive experience with Heather and Constitution Nutrition.

As word spread, Heather acquired a growing number of out-of-town clients—some from as far away as New York—whom she would coach over the internet or phone. So when her husband, a military officer, was transferred to Eglin Air Force Base in Fort Walton Beach, Fla., in 2015, Heather decided it made sense to continue operating Constitution Nutrition from her new home.

But then the state came knocking in the guise of a prospective client.

In March 2017, Heather received an email from a man calling himself Pat Smith who said he had seen her website and liked what he saw. He said he had tried several weight-loss programs to no avail and asked what information Heather would need from him to personalize a weight-loss plan and what her program would include. Heather responded but heard nothing back until May, when she was served with a cease-and-desist letter ordering her to stop giving dietary advice and fining her $754.

It turned out that Smith, in fact, was not a potential customer but an investigator from the Florida Department of Health. His March email had been part of a sting operation prompted by a complaint filed by a licensed dietitian, alleging Heather had been engaged in the unlicensed practice of dietetics/nutrition.

On average, it takes 12 times as much education and experience to obtain a cosmetology license as it does to obtain an emergency medical technician (EMT) license.

Under Florida law, offering paid, individualized dietary advice requires permission from the government in the form of a dietetics/nutrition license. Obtaining a dietitian license requires a bachelor’s degree in nutrition or a related field, 900 hours of supervised practice, passage of a dietitian exam, and payment of $165–$290 in fees to the state. The unlicensed practice of dietetics/nutrition is a first-degree misdemeanor punishable by up to a year in jail and $1,000 in fines per offense. The Department of Health can also seek civil fines of up to $5,000 per day for each day a violation occurs.

Heather was unwilling to run that risk. Since the only other alternative was to become a fully licensed dietitian/nutritionist—a process that would take years and cost tens of thousands of dollars—Heather had no real choice but to close her business.

credit: Getty Images

credit: Getty Images

Occupational Licensing: A National Problem

Heather’s story is not unique. Today, more Americans than ever are finding they need a government permission slip—in the form of an occupational license—to work. In the 1950s, only about one in 20 American workers needed a license to do their job. That figure now stands at roughly one in four.

But the growth of licensure is only the beginning of the problem. Licensing requirements for lower-income occupations are frequently burdensome and irrational. In the Institute for Justice study License to Work, Lisa Knepper, Kyle Sweetland, Jennifer McDonald, and I gathered the licensing requirements for 102 lower-income occupations across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Those requirements included days devoted to education and experience, number of exams, fees, minimum age, and minimum grade level. We found that, on average, licenses to work in lower-income occupations take about a year of education and experience, one exam, and $267 in fees. This means aspiring workers in fields as diverse as auctioneering, cosmetology, and tree trimming spend significant amounts of time and money earning a license rather than earning a living.

For example, the most onerous license in our study was for interior designers. In the states that license the occupation, aspiring workers typically must spend six years in education and experience, pass a costly national examination, and pay almost $1,500 in fees. Licensing proponents assert these requirements are vital to protect consumers, but the vast inconsistencies we find in licensing requirements cast doubt on such claims.

First, the majority of occupations in our study are unlicensed by at least one state and often by many states. For example, interior designers are licensed by only three states and the District of Columbia. Tree trimmers are licensed by seven states. Furniture upholsterers are licensed by 10 states. If tree trimming were truly risky, we would expect the occupation to be licensed by more than seven states. Put differently, the fact that 43 states and D.C. do not see fit to license tree trimmers suggests they pose no threat to public health and safety; the seven states that license them could likely scrap their licenses and see no ill effects.

credit: Getty Images

credit: Getty Images

Second, state licensing requirements for the same job often vary greatly. Among the 30 states that license auctioneers, for example, Vermont requires only nine days of education or experience, Louisiana requires only seven, and 11 others require none. Yet four states require a year or more. It defies credulity that auctioneering in those four states is so different from auctioneering in the other 26 licensed states that all this additional training is really necessary.

Third, licensing requirements are often out of proportion to the health and safety risks posed by an occupation. For example, on average, it takes 12 times as much education and experience to obtain a cosmetology license as it does to obtain an emergency medical technician (EMT) license. And this is not an anomaly; 73 occupations in our study have greater average training requirements than EMTs.

Inconsistencies like these illustrate how erecting licensing hurdles often have little to do with protecting public health and safety. Instead, occupational licenses seem primarily to serve to keep some people out of occupations so those who are already in can enjoy an economic benefit.

And there’s the rub—licenses are, at their core, anticompetitive. Legislatures create them not at the behest of harmed consumers or concerned citizens, but at the request of those in the industry to be licensed.

These requests, as William Mellor and I detail in our 2016 book, Bottleneckers: Gaming the Government for Power and Private Profit, typically come as part of multi-year industry lobbying campaigns mounted in state capitals. Such campaigns often involve coordinating letter-writing efforts, inviting legislators to the workplace to familiarize them with the occupation and cultivate relationships, making strategic campaign contributions, giving special awards to legislators, and packing legislative hearing rooms with members of the industry during testimony claiming licensing is necessary to protect the public.

Scant support is provided for these assertions, and for good reason—most research has failed to find a connection between licensing and service quality or safety. However, there is ample evidence that licensing comes with significant costs, including higher consumer prices and fewer job opportunities. Indeed, economist Morris Kleiner of the University of Minnesota estimates licensing results in 2.8 million fewer jobs with an annual cost to consumers of $203 billion.

And that is only the beginning. Kleiner and other colleagues have also found licensing restricts interstate mobility. Because of significant variability in licensing requirements, licensed workers moving to another state may discover that their new state imposes heavier requirements, forcing them to acquire additional credentials or even start over. Unlicensed workers may find that they need to become licensed for the first time, even if they led successful careers before moving, or else give up their work. Such licensing barriers often make little sense: workers do not become unqualified by crossing a state border. Moreover, these requirements create a disincentive for people to move to where the jobs are and for entrepreneurs to relocate to more desirable markets.

These barriers are particularly burdensome for military families like Heather’s. When the military relocates service members from one state to another, their spouses may find that their credentials from State A are not recognized in State B or that they need a license from State B to practice an occupation they practiced lawfully and successfully without a license in State A. Obtaining the requisite credentials may be expensive and time-consuming—or even impracticable given the likelihood of subsequent relocations.

Research has also found that licensing laws may contribute to criminal recidivism. Many former offenders lack the resources to navigate the licensing process—even when they are allowed to participate in it. Whether through blanket bans that prohibit anyone with a criminal conviction from obtaining a license or through “good character” provisions that grant licensing boards discretion to deny licenses due to an applicant’s criminal record, states often exclude former offenders from the licensing process—a sad irony given states often spend enormous sums training inmates to acquire job skills. Such regulations make it even harder for former offenders to find meaningful employment and stay on the right side of the law.

Reforming Occupational Licensing

Fortunately, with the growth of licensing has come a greater awareness of its costs; that awareness has led to recent interest in and momentum toward reform. In response to this welcome development, we propose a guiding principle and framework for approaching occupational regulation more generally: Any regulation should be no more burdensome than needed to address present, significant, and substantiated harm from an occupation.

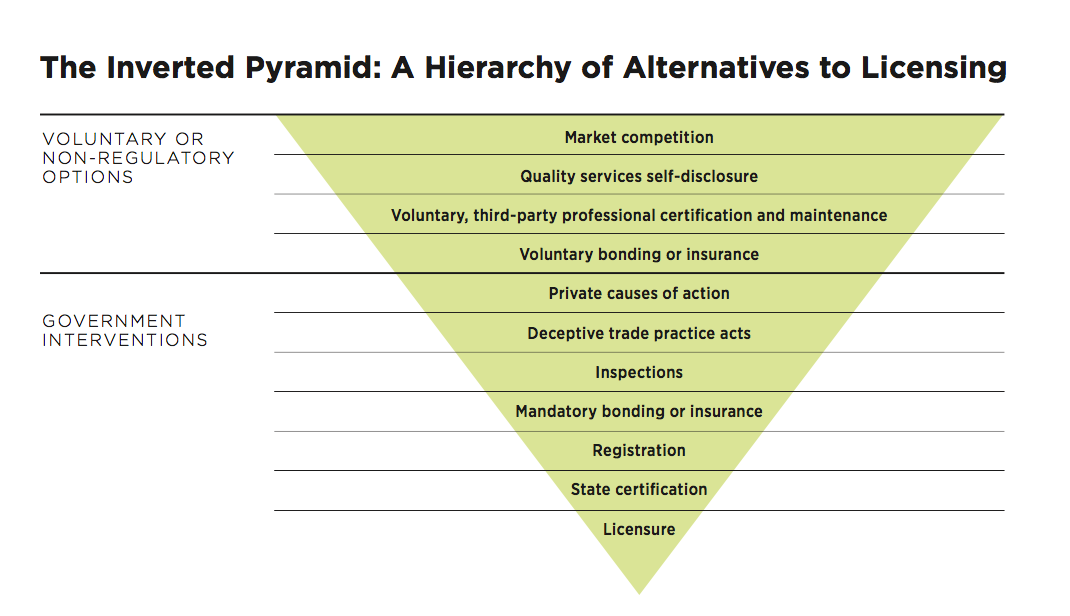

Too often, occupational regulation is seen as a binary choice between no licensing and licensing. Yet this ignores a range of other regulatory options that can protect the public as well as or better than licensing without imposing its costs, which brings us to our proposed framework—the inverted pyramid (see figure on page 24). The inverted pyramid presents 10 alternatives to licensing, ranked from least to most restrictive. The top four options, which can be considered voluntary or non-regulatory are:

1. Market competition. Open markets with no or limited government intervention provide the widest range of consumer choices, allocate resources more efficiently, and give businesses strong incentives to keep their reputations as providers of high-quality services. When service providers are free to compete, consumers weed out providers who fail to deliver safe and quality service by (1) denying them their repeat business and (2) telling others about their experience using social media, advice blogs, and services like Angie’s List, Thumbtack, HomeAdvisor, Houzz, and Yelp. Consumers can also, as Heather’s clients did, use such platforms to drive business to providers with whom they had positive experiences.

2. Quality service self-disclosure. Service providers can facilitate market competition and improve the information available to consumers by proactively sharing information about how previous customers have rated their service quality.

3. Voluntary, third-party professional certification and maintenance. Like licensing, third-party certification sends a signal that a service provider has attained a certain degree of education or experience. But unlike licensing, it does so without creating barriers to entry and the consequent trailing costs. This is precisely the approach Heather took to signal to her potential clients that she possessed specialized training as a health coach.

4. Voluntary bonding or insurance. Some services pose greater risks to consumers than others. Voluntary bonding and insurance allow providers of such services to outsource risk management to a third-party company that has a direct financial stake in preventing consumers from suffering harm or loss.

The next six options are government interventions that, although more restrictive than the preceding options, are nevertheless less restrictive than licensure:

5. Private causes of action. These give consumers the right to bring lawsuits against service providers who have injured them. The existence of such rights may compel providers to adopt standards of quality to avoid litigation and an accompanying loss of reputation.

6. Deceptive trade practices acts. All 50 states and D.C. already have deceptive trade practices acts. These consumer protection laws allow attorneys general and consumers to sue service providers engaged in certain practices deemed false, misleading, or deceptive and permit enforcement agencies to prosecute them.

7. Inspections. In settings where the state may have a legitimate interest in instrument or facility cleanliness, inspections may be sufficient to protect the public. Periodic random inspections could also replace the licensing of various trades where the application of skills is repeated and detectable to the experienced eye of an inspector, such as building contractors.

8. Mandatory bonding or insurance. Voluntary bonding or insurance is generally preferable, but states may prefer a mandatory requirement when the risks associated with the services of certain firms extend beyond just the immediate consumer. For example, the state interest in regulating tree trimmers is in ensuring that the service provider can pay for repairs in the event of damage to power lines or to the home or other property of a neighbor who is not involved in the contract between the trimmer and customer.

9. Registration. Registration requires service providers to provide the government with their name, their address, and a description of their services. Registration can deter fly-by-night operators and complement private causes of action because it often requires providers to indicate where and how they can be notified that they are being sued.

10. State certification. State certification differs from third-party certification in that (1) the certifying body is the government rather than a private association and (2) it restricts the use of an occupational title—though not, as licensing does, the practice of an occupation. Under state certification, anyone can work in an occupation, but only those who meet the state’s qualifications can call themselves “certified.”

credit: Getty Images

credit: Getty Images

Finally, at the bottom of the inverted pyramid’s hierarchy is licensure. Only where there is systematic, empirical proof of demonstrated, substantial harms from an occupation that cannot be mitigated by a less restrictive option should policymakers consider this regulation of last resort.

When considering whether to create a new licensing scheme (or perpetuate an existing one), lawmakers should begin by asking whether there is a demonstrated need for the government to regulate the occupation in question. If there is, they should then use the inverted pyramid to select the least restrictive means of addressing the problem.

Within that general framework, there are at least six specific reforms lawmakers can undertake to rein in licensing. The first is to repeal needless licenses. Lawmakers should scrutinize their states’ licensing laws and eliminate any that do not advance public health and safety, replacing them, if necessary, with less restrictive alternatives. This is the most direct way to free in-state workers and entrepreneurs from licensing red tape. And because the most portable license is the one that does not exist, repealing needless licenses is also the best way to welcome out-of-state workers and entrepreneurs.

The second reform is to roll back license creep, which is the expansion of occupational boundaries and accretion of unnecessary occupational rules that stifle competition. Legislators have the authority to revise and clarify licensing statutes and rules to pare back anticompetitive regulations. They should do so by statutorily exempting distinct fields where licensing is unnecessary, revising occupational definitions to permit lower-cost practitioners to provide services they are trained to provide, repealing regulations that allow licensed practitioners to monopolize harmless occupational practices, and repealing regulations that stifle innovative practices by non-licensees. Exempting hair braiders from cosmetology laws or allowing teeth whitening companies to offer services without a dentist license are just two examples.

The third reform is to codify in statute the right to engage in a lawful occupation and empower the courts to enforce it. This would give workers and entrepreneurs stymied by unnecessary licensing laws a new path to challenge them in court and win.

The fourth reform is to implement meaningful sunrise and sunset reviews for licensing laws. When implemented faithfully, these reviews provide meaningful scrutiny to proposed (sunrise) and already enacted (sunset) licensing schemes. Lawmakers should charge an independent agency with reviewing proposed and existing occupational regulations and give it a mandate to protect competition by favoring regulation only in cases of demonstrated harm and by selecting the least restrictive option to address that harm.

Too often, occupational regulation is seen as a binary choice between no licensing and licensing. Yet this ignores a range of other regulatory options that can protect the public as well as or better than licensing without imposing its costs.

The fifth reform is to rein in anticompetitive behavior of licensing boards by establishing meaningful oversight through an independent office in the executive branch. It should be charged with approving or disapproving boards’ rules, policies, and enforcement actions prior to implementation. The supervisory office should be given a mandate to promote competition and to ensure boards adopt the least restrictive means necessary to address proven public health and safety harms.

The sixth reform is to strengthen rights of people with a criminal record to gain meaningful employment by requiring case-by-case decisions on license applicants, demanding substantial proof of risk of harm to deny a license, and allowing occupational aspirants to petition boards for a written determination of whether their criminal record is disqualifying before they invest in required education and training for a license.

The right to earn an honest living—the “free choice of [our] occupations,” as James Madison called it—has always been a fundamental American right. But in recent decades, this right has become increasingly circumscribed by licensing barriers. Fortunately, this problem is solvable. Policymakers, scholars, and opinion leaders left, right, and center are increasingly coming to understand the drawbacks of licensing and calling for reform.

In 2015, the Obama administration called for reforming occupational licensing and provided its own guidelines for reform in a comprehensive report detailing the evidence of harms caused by overzealous licensing regimes. Among those who agree on the need for reform of occupational licensing are the Trump administration, California’s bi-partisan Little Hoover Commission, the Brookings Institution, The Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, and state leaders across the country. Such agreement on practically anything has become quite rare.

Lawmakers can use the guideline and framework presented here to seize this opportunity to reform occupational licensing. A growing body of evidence indicates such reforms will protect the public from the higher prices and poorer service that follows when professions are shielded from competition. Most of all, reforms will protect the rights of Heather and many others to pursue the occupations of their choice.

Mr. Carpenter is a professor at the University of Colorado and Director of Strategic Research at the Institute for Justice, a public-interest law firm specializing in economic liberty cases.