There are four ways in which you can spend money. You can spend your own money on yourself. When you do that, why then you really watch out what you’re doing, and you try to get the most for your money. Then you can spend your own money on somebody else. For example, I buy a birthday present for someone. Well, then I’m not so careful about the content of the present, but I’m very careful about the cost. Then, I can spend somebody else’s money on myself. And if I spend somebody else’s money on myself, then I’m sure going to have a good lunch! Finally, I can spend somebody else’s money on somebody else. And if I spend somebody else’s money on somebody else, I’m not concerned about how much it is, and I’m not concerned about what I get. And that’s government. —Milton Friedman, interviewed on Fox News, May 2004

Just a few years ago, it was hard to find an elected official in either party who didn’t at least pay lip service to fiscal conservatism. Everyone, it seemed, took the above warning from Milton Friedman seriously—and saw the importance of letting people keep their own money. Who can forget the optimistic days of the Tea Party wave, when dozens of new representatives and senators swept into office fired up and ready to slash taxes and spending? Even the gritty standoffs during the Boehner speakership were generally about what the appropriate level of spending reductions should be. Hiking spending was not an acceptable option.

Now, less than 10 years later, those days might as well be a generation ago. Government spending has never been higher, reaching historic highs and supported by majorities in both parties. Two-thirds of it is on autopilot with no reforms in sight, leaping from 31 percent of gross domestic product in 1970 to 62 percent in 2018.

When Congress does take votes, they tend to be on massive packages rather than individual programs and priorities. It has been over 20 years since Congress even finished its own mandated budget process. Instead, most government spending is approved at the eleventh hour, wrapped up in thousand-page omnibus bills that must pass in order to avoid a government shutdown.

In this environment, it’s almost impossible for elected officials to find meaningful ways to cut spending—even if they wanted to.

And it seems not many actually want that at all. Adjusted for inflation, discretionary spending has more than doubled since 1960, increasingly crowding out private sector alternatives in many areas of the economy. The role of government in people’s everyday lives has grown steadily too, with some estimates suggesting that one in three Americans is dependent on government programs in one way or another.

In 2019, the party that swept into office just nine short years ago promising to slash spending now basically ignores the issue altogether. The other major party? Well-known figureheads regularly endorse massive expansions in programs like free four-year college and Medicare for All. The political discussion has shifted so dramatically that 2020 Democratic presidential candidates attempt to distinguish themselves as “moderates” by clarifying that, yes, they do still believe in capitalism.

What’s the Real Problem?

A glance at fiscal policy debates in the United States might give the impression that only one thing matters: Debt and deficits.

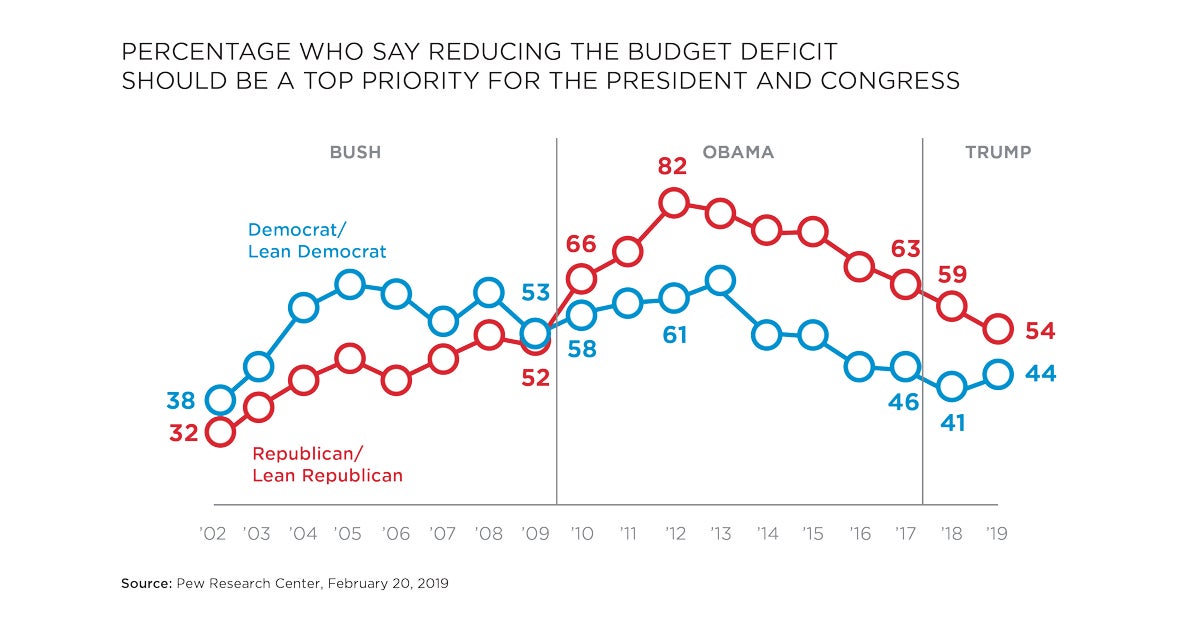

Politicians on all sides beat their chests about the rising numbers—as long as the other party is the one running them up. Public opinion polls are much more likely to ask Americans whether they want to deal with debt and deficits—and they do. That much is obvious and rather consistent across polls and over time. Most recently, a POLITICO/Morning Consult survey showed that about half of Americans want reducing deficits to be a top priority for Congress, while a whopping 81 percent of respondents said the issue was important.

While the level of urgency ebbs and flows (indeed, in 2019, fewer and fewer seem to care about it anymore), a clear majority of Republicans and nearly half of Democrats still want Congress to cut deficits and debt.

But there is a problem.

Few people want to have a serious discussion about the cause of increasing debt and deficits: runaway government spending, and—fundamentally—the expansion of the role of government throughout our lifetimes.

Milton Friedman also famously said:

Keep your eye on one thing and one thing only: how much government is spending, because that’s the true tax […] If you’re not paying for it in the form of explicit taxes, you’re paying for it indirectly in the form of inflation or in the form of borrowing. The thing you should keep your eye on is what government spends, and the real problem is to hold down government spending as a fraction of our income, and if you do that, you can stop worrying about the debt.

Unfortunately, the status quo is not that concerned with keeping its eye on the true tax. In fact, to the degree that commentators talk about the causes of debt at all recently, such discussion has focused exclusively on the impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. While the act is indeed likely to reduce future revenue, this narrative ignores the fact that revenue-to-GDP remains at its historical average and that government receipts have increased in the months since the legislation’s passage.

Meanwhile, it is difficult even to find many recent public opinion surveys that ask about government spending. That’s not to say the American people are opposed to cutting it: A 2017 Pew poll suggested that 45 percent of Americans still support reining in the size and scope of government—with a healthy majority of Republicans and right-leaning independents (74 percent) supporting the goal, even if overall support for big government is on the rise.

But while there might not be overwhelming bipartisan support for belt-tightening, the real problem lies with the other pressures that politicians face.

It is no secret that countless special interests in Washington are dedicated to getting whatever they can out of the federal trough. Likewise, we know that elected officials who publicly support any spending cuts can expect a well-funded and instantaneous backlash claiming that they want to push grandma off a cliff, make America less safe, or whatever else the lobbyists can come up with. It does not take much before most are scared back into line and back into supporting the status quo.

As political scientist David Mayhew famously suggested, politicians act as “single-minded seekers of reelection.” They realize that most of their voters will never know just how much they are voting to spend—and, thanks to special interests, will always know if they ever vote to cut a program. The choice is unfortunately clear.

It is much easier for politicians to simply continue to make vague promises that they will fight for balanced budgets and limited government, and then do little toward accomplishing that goal. Much like a failed dieter going after one last piece of chocolate cake over and over again while pledging to start the diet tomorrow, politicians perpetually promise something in the future and do the exact opposite in reality.

Broken Rules and a Rigged Game

Let us assume for a moment that the long-suffering fiscal conservatives, those beleaguered budget wonks who work in organizations such as The Heritage Foundation and the Institute for Spending Reform, are able to convince most politicians that cutting spending is worth doing.

Let’s imagine that the champions in Congress are no longer a tireless minority but instead a majority ready to make a difference. What has to happen next in order for meaningful reform to become a reality?

First and foremost, Congress has to fix its rules to allow those reforms to happen.

In 1974, coming out of several years of bitter fights with President Richard Nixon on what they saw as abuse of executive power, legislators passed the Budget and Impoundment Control Act, more commonly known as the ’74 Budget Act.

In addition to creating several agencies and limiting presidential power, the act created a system in which Congress passes a budget, a nonbinding roadmap that then guides decisions in 12 appropriations committees that deliberate on exactly how to allocate federal money to various priorities.

Recent research by economists Massimiliano Ferraresi, Gianluca Gucciardi, and Leonizio Rizzo has shown that the ’74 Budget Act was successful in keeping spending lower than it otherwise might have been. However, like most laws, unintended consequences slowly revealed themselves, in the form of increased partisanship in the doling out of federal monies and more frequent brinkmanship between the legislature and the executive.

It has gotten to the point that Congress now rarely follows its own process, and with increasing frequency relies upon continuing resolutions (which are bills that freeze spending at its current level for a set amount of time) or omnibus bills (which roll all spending together into one package that either passes or fails). Most of the time, these packages end up being passed at the last minute before a government shutdown, after being hammered out mostly in secret and being given to legislators just a few hours before they have to take a vote.

The idea of any sort of serious, meaningful spending reform coming out of this system is laughable. A growing majority of spending is not even properly authorized, making even discretionary spending function more like the mandatory programs that are crowding out the budget.

Yet just last year, when legislators had a chance to fix things in the Joint Select Committee on Budget Process Reform, the best they could do was almost agree to a very modest package of reforms that did not contain a real mechanism for restraining spending.

Clearly, reforming the rules is a necessary but insufficient step toward fiscal sanity. Even the best rules are effective only when those to whom they apply feel compelled to abide by them.

Pulling Back the Curtain

The fact is, rules require consequences, and for that reason, fixing the rules and even electing new policymakers will make no difference if their incentives remain the same.

To borrow again from Friedman:

[T]he solution to our problem is [not] simply to elect the right people. The important thing is to establish a political climate of opinion which will make it politically profitable for the wrong people to do the right thing. Unless it is politically profitable for the wrong people to do the right thing, the right people will not do the right thing either, or if they try, they will shortly be out of office.

At present, every incentive in Washington is to spend more. And that’s because for decades, politicians have been able to enter and leave office proclaiming their fiscal conservatism all the while voting for billions upon billions in new spending—and their voters never knew.

Even experts can find it difficult to figure out exactly what might be contained in the things Congress passes, and for everyday voters, it is all but impossible.

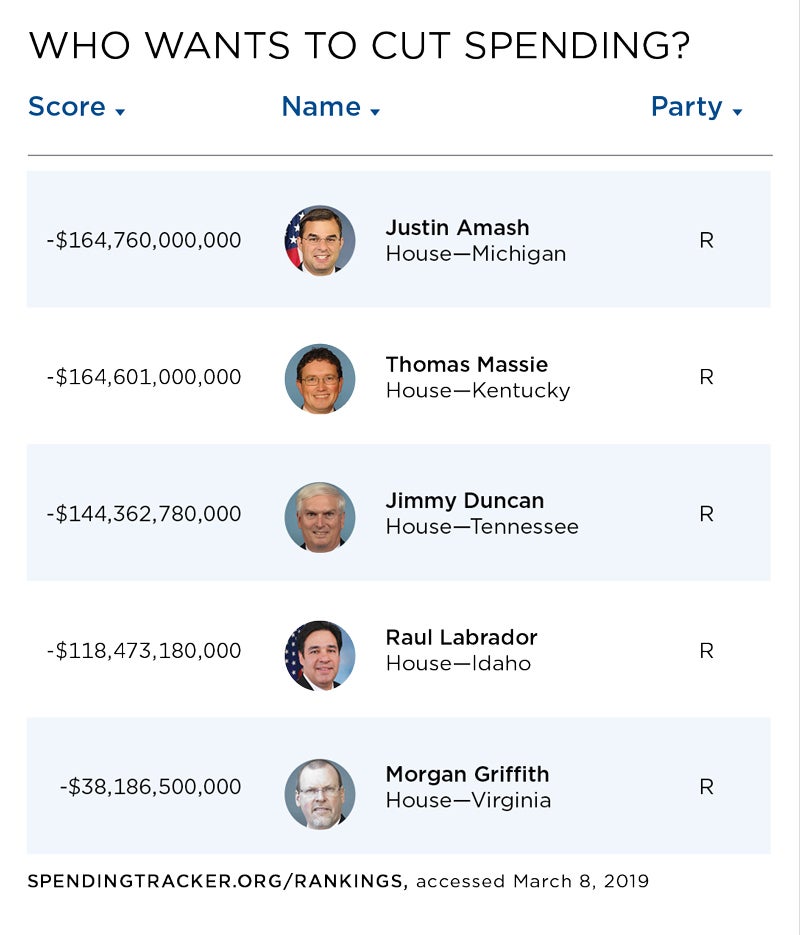

In order to fix this problem, the Institute for Spending Reform created SpendingTracker.org in 2017. This tool is straightforward: It simply tallies every vote for new spending or savings. The results confirm what advocates have long suspected: True fiscal conservatives are few and far between, and perhaps always have been.

In the most recent session of Congress, the 115th, only five members in the House—Justin Amash (R-Mich.), Thomas Massie (R-Ky.), Jimmy Duncan (R-Tenn.), Raúl Labrador (R-Idaho), and Morgan Griffith (R-Va.)—and two in the Senate—Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah)—voted to cut spending on net.

There are, of course, a handful of others who showed restraint. Maybe they did not vote for overall spending cuts, but they worked to reform spending and spent less than others. Overall, though, the picture is bleak. In the 115th Congress, President Trump signed just over $1.7 trillion in new spending into law. The average politician—in both parties—voted to approve just over $1.5 trillion.

Over time, profligacy is common, too. During his time in office, President Obama signed into law nearly $8.5 trillion in spending that otherwise wasn’t slated to occur. As a more specific example, in his last two years, he enacted $1.84 trillion in new spending—of which the median House Democrat voted for $1.81 trillion, and the median House Republican voted for $1.77 trillion. That’s not exactly a stunning difference.

Humorously or sadly—or both, depending on your perspective—current House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has voted for the exact same amount of spending that then-President Obama signed into law.

There are champions in Congress now, just as there have been in the past. But those who are willing to keep spending trillions still remain a clear majority.

What’s the Solution?

For years, fiscally conservative advocates have cried about debt crises, only to be mocked when such crises didn’t occur. We have spoken of the advantages of the free market and the beauty of supply and demand in abstract terms—all while command and control from Washington has been on the march.

In 2019, it seems that fiscal conservatives are at risk of becoming a dying breed, but it does not have to be this way.

In fact, success lies in making the issue real and present for every American. It lies in linking responsibility to every action and highlighting consequences today, not down the road. Now more than ever, we have the tools to do so.

This is not to suggest that we should stop talking about the debt and deficits, but rather, that we do ourselves and our cause a disservice by allowing those issues to distract from the root of the problem: Runaway spending and an ever-

encroaching federal government that knows no limits—regardless of who is in power.

We have to make the case that government spends people’s money badly, regardless of whether the books are balanced.

Every government program, no matter how wasteful or harmful, will have a well-paid defender materialize once it’s at risk of being trimmed. The task, then, is to balance this pressure with real information on the consequences of government spending and who is responsible for it.

In so many walks of life, technology has revolutionized how people think about what is possible. It’s no longer implausible that autonomous vehicles will replace human drivers, or that hyperloops will reinvent transportation altogether. The world of spending policy needn’t be any different. Responsibility may have been impossible a generation ago, but not now.

It is ultimately up to us to make the case why our own generation—not just future ones—is at risk when government grows beyond its proper scope. We must get real with who’s to blame, even if they are on “our side” for other issues. We must take advantage of every tool that new technology offers to help us hold them accountable.

And we must remember that, as Ronald Reagan warned a decade and a half before he first ran for president, freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. So, too, are strong economies, sound money, and the high standards of living that free markets make possible.

Mr. Bydlak is the founder and president of the Institute for Spending Reform, and the creator of SpendingTracker.org.