Second of two articles. The first article can be read here.

Here’s a reality-framing statement for the roughly 190 countries headed to the COP27 climate summit in Egypt that opens on Sunday: Global carbon dioxide emissions in 2022 appear to be higher than pre-pandemic levels, again, and yet, according to the U.N., greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced 43% (relative to 2019 levels) by 2030.

Why is the Conference of the Parties 27 in Egypt likely destined for failure as the summits before it were?

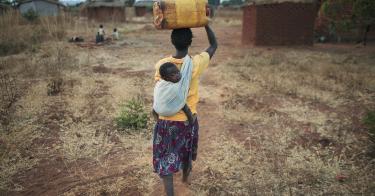

Two-thirds of carbon dioxide emissions growth is coming from developing countries—and for good reason. While many Western nations have enjoyed relatively uninhibited access to energy for more than a century, people in developing countries lack reliable and affordable—or in some cases, any—access to heat, power, and transportation energy.

The demand for reliable, affordable energy is only increasing globally.

An estimated 940 million people around the globe do not have access to any electricity, and roughly 3 billion are without clean cooking fuel.

Lack of access to affordable electricity and fuel has various and wide-ranging consequences. For example, as the World Bank reported in 2013, “more firms cited electricity as a major constraint to doing business than any other factor in nearly [4 out of every 10] client countries for the World Bank Group.”

A provocative—and productive—essay by Vaclav Smil further demonstrates the challenge:

[I]n 2020, the average annual per capita energy supply of about [40%] of the world’s population … was no higher than the rate achieved in both Germany and France in 1860.

In order to approach the threshold of a dignified standard of living, those 3.1 billion people will need at least to double—but preferably triple—their per capita energy use, and in doing so multiply their electricity supply, boost their food production, and build essential infrastructures.

Conventional, carbon-intensive fuels meet 82% of global energy needs, 79% of Americans’ total energy needs, and more than 90% of Americans’ transportation fuel needs. Conventional energy’s share of total global energy consumption has remained roughly unchanged for decades, even as global energy consumption has increased and renewable energy technologies have entered energy markets.

Thousands of products are made with oil, coal, and natural gas as feedstocks, including pharmaceuticals, steel, fertilizers, concrete, and plastics.

Yet, these are the energy resources targeted by the COP summits and by net-zero policies for immediate reductions and ultimately near-elimination from production and use.

The myopic focus of COP summits on reducing greenhouse gas emissions hinders access to affordable energy, particularly for the poorest countries—energy that may ultimately enable them to be more prosperous and, therefore, more resilient against natural disasters. And yet, this fixation has, for example, frustrated construction of a new coal plant in Kosovo to replace “the worst single-point source of pollution in Europe,” and choking off financing for natural gas projects in sub-Saharan Africa.

While those projects (and many others like them) would reduce air pollution, empower those countries to utilize their natural resources, and provide affordable energy, global-warming activists have fixated on emissions from countries that are too poor to even have emissions worth measuring.

Conference of the Parties summits have failed because they presume that the best and only way to understand environmental risk is through the lens of greenhouse gas emissions, and that the best and only way to address that risk is to eliminate use of conventional energy sources for power, heat, and transportation. Consequently, they have attempted to operate independent of physical realities and missed opportunities to improve people’s lives, whatever challenges the future holds.

Acknowledging failure is the first step toward finding a better way. Regardless of how one characterizes global warming as an issue for public policy, policy must be tethered to the realities of how and where people get energy for heat, power, and transportation and what those enable for human well-being.

As aptly stated by one climate scientist: “We need to remind ourselves that addressing climate change isn’t an end in itself, and that climate change is not the only problem that the world is facing. The objective should be to improve human well-being in the 21st century, while protecting the environment as much as we can.”

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal