Inside Defense magazine recently reported that the Department of Defense returned $80 billion to the Treasury in canceled funds over the past six years. That has drawn charges from some corners of Congress that the Pentagon has more money than it knows what to do with.

If only.

While $80 billion is indeed a startling number, the return of canceled funds is more indicative of the byzantine nature of our federal budget than evidence of mismanagement, waste, or excessive appropriations.

Article I of the Constitution states that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” That places Congress, the appropriating branch of government, squarely in the driver’s seat regarding the use of taxpayer dollars.

Congress, therefore, makes rules to ensure that the money it appropriates will be spent on a certain thing during a certain time frame. But while these rules facilitate oversight, they do not ensure efficiency.

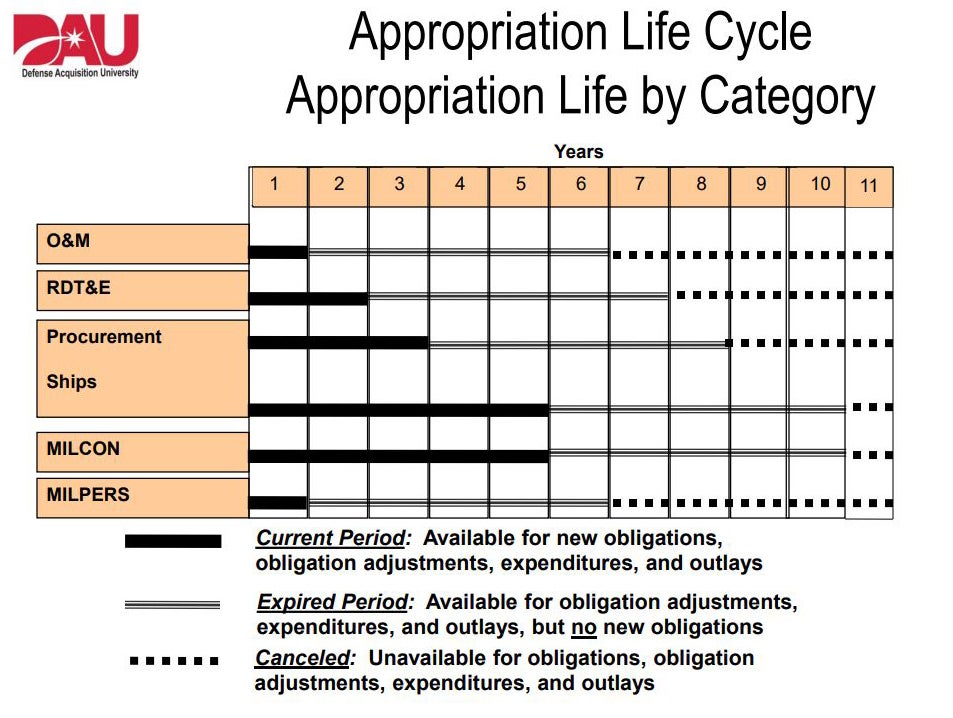

The result is that the defense funds are spread through multiple accounts, each with differing expiration dates and rules. For example, operations and maintenance funds must be obligated in the same year as they are appropriated, whereas military construction funds can be obligated over a five-year period.

After the initial period for all obligating funds, the Defense Department has an additional five years in which it can adjust expenditures and outlays of those funds, but it cannot incur any new obligations.

What the heck does that mean?

Well, suppose that over the five-year period, a project needed less personnel than expected. The Pentagon can’t just take those “savings” and spend it on something else. At the end of the five years, the unspent funds are “canceled” and must be returned to the Treasury.

Those canceled funds, reportedly totaling $80 billion between 2013 and 2018, are the ones that have so recently captured the attention of Congress in news reports.

Naturally, since this is government, it’s not as simple as it sounds. Further complicating the Defense Department’s efforts to budget and spend efficiently is Congress’ all-too-frequent failure to enact appropriations when it’s supposed to.

Too often, lawmakers fail to agree on appropriations by the start of a new fiscal year, leaving government to operate on continuing resolutions—i.e., last year’s budget.

The longer lawmakers dither over appropriations, the less time the Pentagon has to obligate the new fiscal year’s funds. Instead of one year, there might be a little under five months, as was the case in 2017, or nine and a half months, as in 2015.

Adding up all the days spent under a continuing resolution in between 2013 and 2018, the Defense Department lost, on average, four and a half months of every fiscal year.

Considering the reduced time available, it’s impressive that the Defense Department was able to obligate most of one year’s worth of resources in under eight months.

That raises the question of how much does the $80 billion represent of the defense budget. According to the data available, the Department of Defense returned an average of $13.5 billion per year. Over the past six years, the base defense budget (excluding war funding) has averaged $509 billion. Thus, on average, the department had 2.6 percent of its budget canceled.

When you consider that the planning process for the defense budget, under ideal circumstances, starts close to three years before the start of the fiscal year and ends eight months before, getting it 97 percent right is an amazing accomplishment.

If you were budgeting your lunch money for three years from today, you would probably be delighted to get it 90 percent right.

It becomes even more impressive when you consider the volatile and uncertain environments in which the Pentagon operates—namely, war zones, contingency operations, and evolving technologies.

Another important caveat is the “use it or lose it” pressure that exists at every level of every government agency. Washington is littered with stories of financial managers who reach the final months of the fiscal year with leftover money and rush to spend before they have to hand it back.

Economists Jeffrey Liebman and Neale Mahoney have determined that, in the area of information technology, projects approved near the end of the fiscal year have substantially lower quality ratings.

If the choice is between returning the money to the Treasury or making a bad-quality decision with taxpayer dollars, the preference should always be to return the money.

The $80 billion returned to the Treasury is not a sign of waste, mismanagement, or budget padding. Rather, it is a symptom of a budget process that optimizes oversight, not efficiency.

The constraints and limitations that Congress imposes on the Pentagon will inevitably lead to a fraction of the resources being returned to the Treasury. Until we change our current convoluted system, it’s an unfortunate part of the cost of doing business.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal