—Abraham Lincoln, April 6, 18591

Life

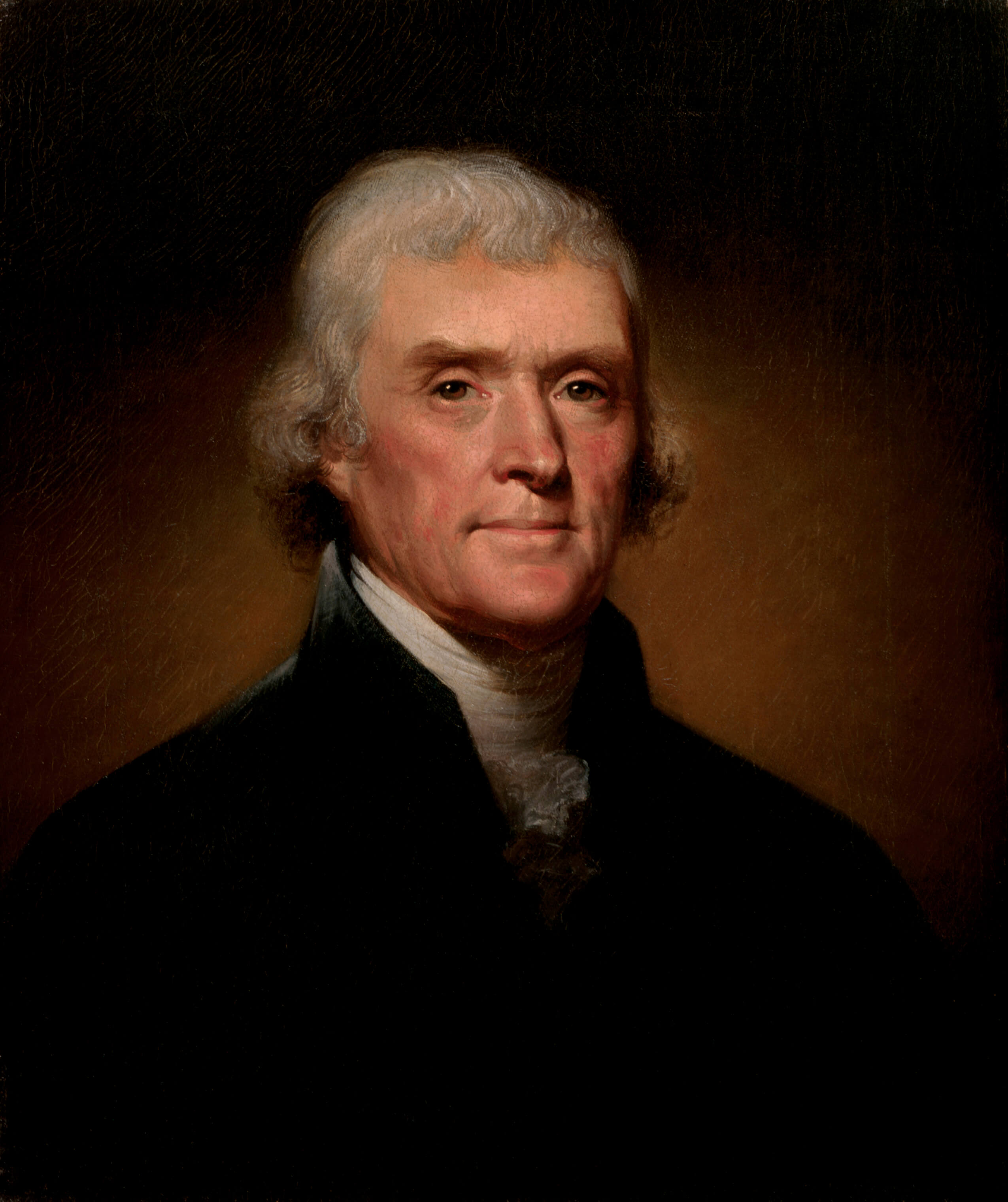

Thomas Jefferson was born April 13, 1743, in Shadwell, Albemarle County, Virginia, the third child of Peter Jefferson and Jane Randolph [Jefferson]. In 1772, he married Martha Skelton Wayles. They had six children, of whom two daughters lived into adulthood. Martha died in 1782. Some historians hold that Jefferson later fathered children by his slave, Sally Hemings; other scholars dispute this claim. Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, at Monticello, his home in Virginia, where he is buried.

Education

Jefferson’s early education was provided by tutors and schools run by Virginia clergymen. He attended the College of William and Mary from 1761–1762 and then studied law under George Wythe.

Religion

Anglican/Episcopalian

Political Affiliation

Co-founder (with James Madison) of the Republican Party in 1792

Highlights and Accomplishments

1769–1775: Virginia House of Burgesses

1775–1776: Virginia Delegate to the Second Continental Congress

1776–1779: Virginia House of Delegates

1779–1781: Governor of Virginia

1782–1784: Virginia Delegate to the Confederation Congress

1785–1789: Minister to France

1790–1793: Secretary of State

1797–1801: Vice President of the United States

1801–1809: President of the United States

1819: Founder, University of Virginia

More than two centuries after his passing, Thomas Jefferson remains one of the most celebrated and consequential statesmen of the American Founding. Jefferson served for more than 30 years in political offices of the highest responsibility. This distinguished career embraced the entire history of the Founding, from America’s quest for national independence to the firm establishment of the system of constitutional self-government that persists to this day. During the American Revolution, Jefferson was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress and then governor of Virginia. Under the Articles of Confederation, he returned to national office as the American minister to France. Finally, after the Constitution was ratified and the new government was put into operation, Jefferson served as the nation’s first Secretary of State, its second Vice President, and its third President, administering the nation’s highest office for two full terms before turning to a lengthy and well-earned retirement.

Over the course of these momentous decades, Jefferson worked closely with—and sometimes against—the other titans of the Founding generation: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison. Amid the controversies that divided the nation in the first few years after ratification of the Constitution, Jefferson emerged as the principal figure in one of the nation’s first political parties. It is a testament to his political stature that this party first took its name from that of its great leader. The Jeffersonians, also called the Jeffersonian Republicans, later were known as Democratic Republicans and then simply as the Democratic Party. Jefferson was thus the founder of the nation’s oldest political party, which still plays a key role in shaping American politics.

These deeds alone constitute a record of achievement that almost any politician would envy. Jefferson’s importance to our country, however, resides not only in his deeds, but also in his thoughts and words—that is, in the political ideas to which he gave such powerful and memorable expression. As the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson formulated the bedrock moral and philosophical principles on which our government rests. Although Jefferson played no direct part in framing the Constitution, his interpretations of it have powerfully shaped the thinking of many Americans, even down to the present day.

Few Americans—and, for that matter, few statesmen anywhere in the world—have left such a lasting impression on their country. Jefferson’s importance is visible in the impressive monuments erected to his memory. He is one of only four Presidents honored on Mount Rushmore and one of only a handful whose memorials surround the National Mall in Washington, D.C. His prominence in the imagination of our people is evident in the vast number of schools, towns, and counties that bear his name. Moreover—and perhaps more important than all these tangible signs of respect—Jefferson’s ideas continue to be invoked and his legacy continues to be debated by generations of Americans born long after he died. It is no exaggeration to say that we cannot fully understand America without understanding Thomas Jefferson’s contributions to its political development.

Natural Rights and Government by Consent

Thomas Jefferson is perhaps most famous as the principal author of America’s Declaration of Independence. The Continental Congress entrusted the important task of developing this pivotal statement to a committee of five men: Jefferson, Franklin, Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. Jefferson’s august colleagues on this committee then selected him to write the initial draft. The final version of the Declaration is not entirely Jefferson’s work. The committee and the Congress made some revisions. Nevertheless, the officially adopted public text closely reflects the work of Jefferson’s pen, and he could claim with just pride to be the “Author of the American Declaration of Independence”—one of the three accomplishments he listed on his tombstone.

As author of the Declaration, Jefferson listed the many specific grievances that the colonists believed justified their decision to break with the mother country once and for all, establishing America as an independent nation. Jefferson also did something else of much greater and more lasting significance: He used the opening paragraphs of the Declaration to express the fundamental moral, political, and philosophical “truths” that “we” Americans “hold…to be self-evident.” These truths are still familiar to and cherished by almost all Americans: “that all men are created equal”; that they are “endowed by their creator” with certain fundamental and “inalienable rights,” including those “to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”; that governments are “instituted” by “the consent of the governed” in order to protect these rights; and that the people may “alter and abolish” their forms of government whenever they become “destructive” of their rights, and institute a new government that they believe will protect their rights more effectively.2 Jefferson was thus instrumental in establishing, or at least in memorializing, something that makes America unusual among the nations: its commitment to a specific political creed that it believes is required by universal principles of justice—its sense that its very identity is bound up with certain political axioms that it cannot betray without betraying itself.

Thanks to Jefferson’s inclusion of this statement of principles, the Declaration has been able to function as a kind of touchstone of American politics, a moral standard that statesmen and citizens can consult from generation to generation, especially when grappling with issues in relation to which the nation seems to have strayed from its Founding commitments. As a result, the Declaration—and Jefferson’s words—have played a key role in many of America’s most important political controversies. In the 1850s, Abraham Lincoln appealed to the Declaration’s doctrines of equality and consent to contend that America could not tolerate slavery’s further extension without undermining the nation’s commitment to freedom and self-government. A century later, Martin Luther King, Jr., cited the claim that “all men are created equal” in his celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech calling for an end to racial segregation.

Some have used the word “radical” to describe the Declaration’s political teaching.3 Is this an accurate characterization? Was Jefferson himself a political radical? These are complicated questions, and it is necessary to explore them to gain a full understanding of the political thought of the Founding and Jefferson’s contributions to it.

The Declaration was certainly radical in its insistence on the centrality of the rights and consent of the people. Here it departed from older traditions of thought that emphasized deference to established forms of government. For many generations, Europeans had tended to think that their ancient monarchical and aristocratic regimes could justly demand the people’s obedience because they were established by divine right, were part of a precious civilizational inheritance built up under the guidance of God’s providence, or (at the very least) were believed to be an immovable fact of life to which people had to submit to maintain any kind of tolerable social order. In contrast to such thinking, the Declaration held that the people have the authority to create their own governments in order to protect their rights.

Nevertheless, neither Jefferson nor anybody else considered these principles radical in the American context. In writing the Declaration, Jefferson had drawn on a body of political thought—especially the work of the English political philosopher John Locke—that had powerfully influenced the American colonists’ thinking over a period of many years. Accordingly, looking back from his retirement, Jefferson remarked that the Declaration had been intended as “an expression of the American mind,” giving “the common sense” on the issues at stake, and not as seeking to “find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of.”4

In fact, there are some senses in which the Declaration’s principles are not radical but conservative in their character. Jefferson was careful to temper the Declaration’s assertion of a popular right to revolution with a reminder that such a right must be exercised with due caution and for sufficiently weighty reasons. Thus, he included in the Declaration the observation that “prudence”—a virtue the Founders recognized as essential to wise statesmanship—“will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes.”

For Jefferson and the Founding generation, revolution was not the first resort every time a government happened to have violated some of the rights of the governed; rather, it was the last resort to which the people were compelled when the government clearly aimed “to reduce them under absolute despotism.” Moreover, by appealing to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God,” the Declaration reflected a kind of thinking—the effort to ground moral and political standards in the order of nature—that had informed Western civilization since the emergence of political philosophy among the ancient Greeks.5 Thus, Jefferson later indicated that the Declaration reflected the teaching not only of the modern “elementary books of public right” by authors such as Locke and Algernon Sidney, but also ancient ones by Aristotle and Cicero.6

The idea that Jefferson himself could be called a radical has some basis in his differences with some of the other Founders. The principles of the Declaration represented a common ground for the Founding generation, but different figures interpreted and applied them differently—and Jefferson can be found sometimes pressing them to extremes that other Founders rejected. Jefferson, for example, once wrote to James Madison that “the earth belongs in usufruct to the living” and that, accordingly, “the dead have neither powers nor rights over it.”7 Jefferson drew the conclusion that constitutions of government and even ordinary laws ought to expire at the end of every generation so that the coming generation has a genuine right to consent to them or to different ones if they so choose. Writing in reply to his friend, Madison suggested that such a doctrine was “liable in practice to some weighty objections.” A constantly changing constitution, Madison observed, would forfeit the habitual respect of the people that is a beneficial support to any government, and the recurring constitutional revisions would create factional conflict and “agitate the public mind more frequently and more violently than might be expedient.”8

Moreover, where men like Washington and Hamilton were horrified by acts of lawless opposition to the government, such as Shays’ Rebellion and the later Whiskey Rebellion, Jefferson was notably more tolerant of such extra-legal assertions of the people’s power, viewing them as necessary to preserve liberty in the face of a potentially overbearing government. “I hold it,” he famously wrote to Madison, “that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.” Accordingly, he continued, “honest republican governors” should be “so mild in their punishment of rebellions, as not to discourage them too much” since they provide “a medicine necessary for the sound health of government.”9

Nevertheless, unlike some later American radicals who have misunderstood or abused the Declaration’s claim that “all men are created equal,” Jefferson was no egalitarian. For him, as for the rest of the Founders, the crucial moral fact that all are equal in their fundamental rights—to life, liberty, and property—did not mean that all would be equal in their accomplishments, status, or power. Jefferson made this clear in his private and public pronouncements. Writing to his friend and former political rival, John Adams, Jefferson admitted that “there is a natural aristocracy among men” based on “virtue and talents.” This aristocracy, he added, was “the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.” Remaining true to the Declaration’s claim that a just government must rest on the consent of the governed, Jefferson never suggested that this natural aristocracy had any right to rule, but he did observe to Adams that the best form of government would provide “most effectually for a pure selection” of the natural aristocrats “in the offices of government” so that their “virtue and wisdom” could be used in managing “the concerns of the society” successfully.10

In a similar spirit, Jefferson, in his Second Inaugural Address as President, expressed it as his “wish”—and the common wish of all Americans—that “equality of rights be maintained,” as well as “that state of property, equal or unequal, which results to every man from his own industry, or that of his fathers.”11 Unlike some contemporary left-wing critics of American society, Jefferson saw nothing morally suspect in the inequalities of wealth that arise in a free society from different degrees of success in work or even from inheritance.

Perhaps slavery, more than any other single issue, best illustrates the ambiguities of Jefferson’s radicalism. On the one hand, Jefferson came from a slave state, Virginia, and was himself a lifelong slave owner. Unlike George Washington, Jefferson made no provision to free his slaves upon his death. Although he urged his home state to adopt a plan of gradual emancipation, the abolition of slavery was no part of Jefferson’s program as a statesman at the national level. On the other hand, Jefferson never let his own or his fellow citizens’ personal economic interest in slavery blind him to its incompatibility with the principles he had expressed for the country in the Declaration of Independence. Nor did he permit such considerations to deter him from openly declaring the injustice of slavery. In his 1774 Summary View of the Rights of British America, Jefferson criticized King George for protecting the slave trade, an “infamous practice” that “deeply wounded” the “rights of human nature.”12 Jefferson included an even stronger denunciation of the slave trade in his original draft of the Declaration, although the Congress removed this language from the final version.13 In his discussion of slavery in his Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson famously remarked: “Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just” and “that his justice cannot sleep forever.”14

As a man and as a politician, Jefferson was a pragmatist whose actions in opposition to slavery were limited by how deeply rooted it was both in his own life and the life of the nation. Nevertheless, he deserves considerable credit for his clear and repeated public condemnations of it, which helped to guide later generations of statesmen like Abraham Lincoln who led the efforts to restrict and finally destroy American slavery.

Strict Construction and States’ Rights

Thomas Jefferson’s thought is also essential to understanding our nation’s other most important Founding document: the Constitution. To be sure, Jefferson played no direct role in framing the original Constitution (which was done while he was on the other side of the Atlantic serving as minister to France) or of the Bill of Rights (which was drafted by Congress while Jefferson was serving in the executive branch as the nation’s first Secretary of State). Nevertheless, Jefferson was deeply involved in the country’s early debates over the meaning of the Constitution, and the views he expressed had a lasting influence on many Americans, both in his own time and in later generations.

In general, to use terms popularized later in American history, Jefferson was a proponent of “strict construction” and “states’ rights.” That is, he favored a narrow interpretation of the powers of the federal government, partly out of a desire to protect individual liberty, but partly as a way to safeguard states’ powers from national encroachments. Here it is helpful to think of Jefferson’s position in relation to the contending factions in the great debate over whether to ratify the Constitution in the first place. Jefferson could be counted as a Federalist in the sense that he favored ratification of the Constitution because he agreed that the government under the Articles of Confederation was too weak to govern the country effectively. At the same time, he was also very sympathetic to Anti-Federalist fears of an excessively strong central government that would eventually usurp all political power and destroy the remaining sovereignty of the state governments. In light of these latter concerns, Jefferson favored a more limited interpretation of the federal power under the Constitution than some other leading Founders wanted.

Jefferson first developed his defense of strict construction of the federal power in debates with Alexander Hamilton and later, more generally, in opposition to the policies of the Federalist Party. Jefferson’s constitutional contest with Hamilton deserves to be classed as one of the greatest political rivalries in American history, giving rise to the nation’s first party system, with Federalists favoring an expansive, Hamiltonian reading of the powers of the national government and Jeffersonian Republicans contending for stricter limits. These disputes began to emerge as early as George Washington’s first term as President while Hamilton was serving as Secretary of the Treasury and Jefferson was serving as Secretary of State.

Their first important constitutional disagreement concerned Hamilton’s plan for a national bank. After the law to create this institution was approved by both houses of Congress, President Washington, uncertain of its constitutionality, sought the advice of the members of his Cabinet. In his written opinion submitted to the President, Jefferson argued strenuously that the Constitution gave Congress no power to charter a bank. Such an authority, he noted, was nowhere to be found among the enumerated powers of the federal government: those expressly listed in Article I, Section 8.

This argument, however, was not in itself conclusive. Perhaps the bank could be justified, as Hamilton suggested, under the Necessary and Proper Clause—that provision at the end of the enumeration that gave Congress the power “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers.” According to Hamilton, the bank could be understood as necessary to the successful execution of the federal government’s enumerated powers to raise taxes, borrow money, and regulate commerce among the states. For Jefferson, Hamilton’s argument depended on an unreasonably and dangerously loose interpretation of the term “necessary.” A bank, Jefferson contended, was not really necessary to the execution of these enumerated powers because all of them could be executed without it. It was at best only “convenient” for their execution.15 Hamilton’s interpretation, Jefferson believed, pushed the federal power further than it was intended to go.

A similar dispute arose later over Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures, which called for federal “bounties” or subsidies to promote American manufacturing. Hamilton argued that such a spending policy could be justified under the constitutional provision authorizing Congress to raise taxes and spend money for the sake of the “general welfare.” Jefferson, however, thought that Hamilton was again seeking to take the federal power beyond its proper limits because the Constitution did not expressly contemplate paying out federal money in bounties to private persons.16

For Jefferson, much more than a couple of arguable constitutional violations was at stake in these disagreements. He believed—and argued strongly—that Hamilton’s interpretations tended to destroy the constitutional limits on the federal government’s power. Hamilton’s approach to the Necessary and Proper Clause was so loose that it could justify practically anything because there are innumerable policies that could plausibly be presented as useful or convenient (as opposed to truly necessary) to the execution of the enumerated powers.17 Moreover, Jefferson held that Hamilton treated the General Welfare Clause as a blanket authorization for Congress to do anything that it believed would be good for the United States.18

The effect of Hamilton’s constitutionalism was therefore to destroy the enumeration of powers as a real limit on the authority of the government and thus to undermine one of the main purposes of the Constitution itself. In Jefferson’s view, Hamilton was a threat not only to the Constitution, but even to the fundamental American commitment to republican self-government. Jefferson warned President Washington that he feared Hamilton and his party were seeking to eliminate the Constitution in order eventually to introduce a monarchy in its place.19

As it turned out, Jefferson’s fears for the future of American constitutionalism and republicanism did not end with Hamilton’s departure from national office. In 1798, after Hamilton had left the Treasury and Washington had retired from the presidency, the Federalist Congress passed and President John Adams signed into law the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson, now Vice President under Adams, viewed these acts as another example of the Federalist Party’s willingness to violate the Constitution. In this case, however, Jefferson viewed the danger as so serious that he felt called not only to disagree, but even to encourage resistance. To that end, he drafted for the Kentucky Legislature a set of resolutions urging the state governments to unite in opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts. Here he collaborated with his friend and co-founder of the Jeffersonian-Republican Party, James Madison, who authored a set of protest resolutions for the Virginia Legislature, making arguments similar to (but not identical to) Jefferson’s.

According to Jefferson’s Kentucky Resolutions, the Alien Acts exercised powers not granted by the Constitution. They violated the separation of powers and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment by giving the President broad authority to order certain foreigners to leave the country. The Sedition Act, which punished false and defamatory publications against the government, claimed to exercise a power over the press that was not granted in the Constitution’s enumeration of powers—and in fact was explicitly ruled out by the First Amendment’s prohibition on any law “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” Jefferson went further, however, and put forward a theory proposing that state governments had the authority to judge for themselves whether the federal government had gone beyond its legitimate powers and violated the Constitution.

For Jefferson, the Constitution was properly understood as a “compact” among the states by which they had agreed to create the federal government for certain limited purposes, leaving to themselves “the residuary mass” of authority. Therefore, any act of the federal government that went beyond the “definite powers” delegated to it by the states was “unauthoritative, void, and of no force.” Moreover, Jefferson continued, the Constitution did not make the federal government or any part of it, such as the Supreme Court, “the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself, since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers.” Rather, because the Constitution was a compact among the states, each state, as a party to the agreement, had “an equal right to judge for itself” whether the federal government had violated the Constitution and what “mode and measure of redress” ought to be pursued in such a case. Later in his draft of the resolutions, Jefferson argued that when the federal government acted outside its proper powers, “a nullification of the act” by the state government “is the rightful remedy” because “every state has a natural right” to “nullify” by its “own authority all assumptions of power” within its limits that are not justified by the constitutional compact among the states.20

Jefferson left America a mixed legacy as a strict constructionist and states’ rights constitutionalist. His narrow interpretation of the federal power even complicated his thinking about his greatest accomplishment as President. Because the Constitution did not expressly authorize the government to acquire new territory, Jefferson worried that the Louisiana Purchase, which paved the way for America to become a great and powerful nation, was unconstitutional—although he went ahead with it anyway.21 This example and many others suggest that Jeffersonian strict construction was not adequate to the needs of the nation. The Supreme Court itself came to this conclusion later when, in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819),22 it affirmed the constitutionality of the Second Bank of the United States and explicitly rejected the narrow interpretation of the Necessary and Proper Clause that Jefferson had advanced a generation before. Later Supreme Court rulings also affirmed the constitutionality of federal spending programs that depended on a broad interpretation of the General Welfare Clause.

It would seem, then, that, despite the crushing political blow that Jefferson and his party dealt to the Federalists in the election of 1800, Hamiltonian constitutionalism prevailed in the end. Nevertheless, Jefferson’s concerns and arguments continue to exert influence even today. The need to protect the legitimate powers of the state governments and to avoid interpretations of the federal powers that would render them unlimited in practice has been invoked by the Supreme Court many times in our nation’s history when the federal government has sought to overstep its proper constitutional boundaries.

Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion in McCulloch also made a point of rejecting Jefferson’s compact theory. The Constitution, Marshall observed for a unanimous Court, was an agreement among the people of the United States as a nation, not among the states. Despite this ruling, Jefferson’s account of the Constitution as a compact among sovereign states continued to exert influence—and, one might say, work mischief—for many decades. In the 1830s, the state of South Carolina asserted that its sovereignty as a state included a right to nullify the federal tariff and even to secede from the Union. A generation later, many Southern states, influenced by such thinking, attempted to secede from the Union and thereby precipitated the crisis of the American Civil War—with the Union’s victory finally putting an end to such extreme theories of state sovereignty.

It would be unjust, however, to cast too much blame on Jefferson for the acts of later Americans who carried his arguments further than he had himself. Jefferson explicitly repudiated secession and disunion, saying that those who took such a step would be perpetrating an “act of suicide on themselves and of treason against the hopes of the world.” Moreover, whatever the merits or demerits of Jefferson’s compact theory, we may certainly acknowledge that it is an inherent feature—and advantage—of American federalism that state officials can find ways, without going so far as to claim a power of “nullification,” to shelter their citizens from what they think are abuses of the federal power. Attempts to do so have continued down to the present day.

Church and State, Religion and Politics

As historian Wilfred McClay has observed, America at the time of the Founding was dominated by two “distinctive intellectual currents”: Protestant Christianity and Enlightenment rationalism.23 Jefferson clearly belonged more to the Enlightenment current. This is not to say that Jefferson was irreligious. He was raised in Virginia’s Anglican Church, remained an active member in his young manhood, and attended public religious services during his presidency. Nevertheless, Jefferson’s Enlightenment leanings were evident in his choice to give a prominent place at Monticello to portraits of Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and John Locke—as well as in his remark to Alexander Hamilton that he regarded them as his “trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced.”24 Moreover, Jefferson’s deviation from traditional Christian orthodoxy was displayed in his compilation of the moral teachings of Jesus, carefully omitting references to miracles and claims of Jesus’ divinity, which he believed did not originate with Jesus but had been added by his followers.

Throughout his life, Jefferson considered himself a staunch champion of religious liberty. He was the author of Virginia’s Statute for Religious Freedom, one of the three accomplishments he memorialized on his tombstone. In memorable phrases characteristic of Jefferson’s public eloquence, the Statute denounced as “sinful and tyrannical” any measure “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves” and held that “our civil rights have no dependance on our religious opinions, any more than on our opinions in physics or geometry.” The law went on to provide that “all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion,” which would in no way “diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.”25

Jefferson also showed his understanding of the proper relationship between politics and religion in his conduct of the presidency. Here, too, his choices bring to light differences of opinion among the Founders about the meaning of the Constitution. Both of his great presidential predecessors, George Washington and John Adams, had issued formal Thanksgiving proclamations calling on their fellow citizens to set aside a day for prayer and expressions of gratitude to God for his many blessings upon America. Jefferson declined to do so, believing that the practice was inconsistent with the Constitution. “In matters of religion,” he observed in his Second Inaugural Address, “I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the Constitution independent of the powers of the general government.” Therefore, he explained, he had “undertaken, on no occasion,” to “prescribe” any “religious exercises.”26

Jefferson’s most famous and consequential statement on the question of religion, politics, and the Constitution can be found in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in which he stated that “religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith and worship,” and “that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, not opinions.” Accordingly, he continued, “I regard with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people”—the First Amendment—“which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between church and state.”27

Both Jefferson’s “wall of separation” metaphor and the principles he expressed in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom have powerfully influenced the Supreme Court’s understanding of the First Amendment over the past several decades in cases limiting the government’s ability to promote religion. Contemporary critics of the Court’s Jeffersonian interpretation have appealed more to the precedents set by Washington and Adams, which give more constitutional scope to government encouragement of religion.

In view of this influence, Jefferson has been treated as something of a hero by extreme American secularists who wish to see religion completely banished from public life. Here again, however, Jefferson’s thought is more subtle than might be suggested by those who try to appropriate it for their own purposes.

While Jefferson held that the federal government had no power to promote religion, he did not believe that religion was politically irrelevant. On the contrary, he agreed with most of the other leading Founders that religion is a necessary support to the morality that sustains a free and just society. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, he suggested that “the liberties of a nation” cannot be “secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are the gift of God” and “are not to be violated but with his wrath.”28 Accordingly, Jefferson thought it appropriate to use his First Inaugural Address as an occasion to praise religion by numbering among the nation’s “blessings” a “benign religion, professed indeed and practiced in various forms, yet all of them inculcating honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude and the love of man, acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here, and his greater happiness hereafter.”29

A Complicated Legacy

As the preceding discussion indicates, Jefferson’s legacy is complicated. On the one hand, he is a powerful symbol of what unifies us as Americans. It fell to him at the moment of the nation’s birth to express the fundamental truths on which our political way of life is established. On the other hand, he is also a symbol of division. He became the founder and leader of a great political party, contending for interpretations of the Constitution that clashed with those favored by other important figures among the Founders. That Jefferson was involved in such controversies in no way diminishes his greatness. Politics is inherently controversial, and all of the towering figures among the Founders were parties to these controversies.

In any case, there is no doubt that Jefferson earned lasting greatness through his contributions to both unity and controversy. When called upon to speak for the nation in the Declaration of Independence, he did it in so powerful and memorable a fashion that it is now almost impossible to imagine America apart from the principles he stated and the words he chose to express them. When acting in the realm of constitutional controversy, Jefferson proved himself one of the most energetic and intelligent exponents of ideas that have influenced American politics from his time until our own. No one, not even his critics, can deny that to understand America fully, we must understand the political career and ideas of Thomas Jefferson.

Selected Primary Writings

A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom (1779)30

Section 1. Well aware that the opinions and belief of men depend not on their own will, but follow involuntarily the evidence proposed to their minds; that Almighty God hath created the mind free, and manifested his supreme will that free it shall remain by making it altogether insusceptible of restraint; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments, or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, who being lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in his Almighty power to do, but to extend it by its influence on reason alone; that the impious presumption of legislators and rulers, civil as well as ecclesiastical, who, being themselves but fallible and uninspired men, have assumed dominion over the faith of others, setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and infallible, and as such endeavoring to impose them on others, hath established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world and through all time: That to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors, is sinful and tyrannical; that even the forcing him to support this or that teacher of his own religious persuasion, is depriving him of the comfortable liberty of giving his contributions to the particular pastor whose morals he would make his pattern, and whose powers he feels most persuasive to righteousness; and is withdrawing from the ministry those temporary rewards, which proceeding from an approbation of their personal conduct, are an additional incitement to earnest and unremitting labors for the instruction of mankind; that our civil rights have no dependance on our religious opinions, any more than our opinions in physics or geometry; that therefore the proscribing any citizen as unworthy [of] the public confidence by laying upon him an incapacity of being called to offices of trust and emolument, unless he profess or renounce this or that religious opinion, is depriving him injuriously of those privileges and advantages to which, in common with his fellow citizens, he has a natural right; that it tends also to corrupt the principles of that very religion it is meant to encourage, by bribing, with a monopoly of worldly honors and emoluments, those who will externally profess and conform to it; that though indeed these are criminal who do not withstand such temptation, yet neither are those innocent who lay the bait in their way; that the opinions of men are not the object of civil government, nor under its jurisdiction; that to suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion and to restrain the profession or propagation of principles on supposition of their ill tendency is a dangerous fallacy, which at once destroys all religious liberty, because he being of course judge of that tendency will make his opinions the rule of judgment, and approve or condemn the sentiments of others only as they shall square with or differ from his own; that it is time enough for the rightful purposes of civil government for its officers to interfere when principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order; and finally, that truth is great and will prevail if left to herself; that she is the proper and sufficient antagonist to error, and has nothing to fear from the conflict unless by human interposition disarmed of her natural weapons, free argument and debate; errors ceasing to be dangerous when it is permitted freely to contradict them.

Sect. II. We the General Assembly of Virginia do enact that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.

Sect. III. And though we well know that this Assembly, elected by the people for the ordinary purposes of legislation only, have no power to restrain the acts of succeeding Assemblies, constituted with powers equal to our own, and that therefore to declare this act irrevocable would be of no effect in law; yet we are free to declare, and do declare, that the rights hereby asserted are of the natural rights of mankind, and that if any act shall be hereafter passed to repeal the present or to narrow its operation, such act will be an infringement of natural right.

First Inaugural Address (1801)31

Friends & Fellow Citizens,

Called upon to undertake the duties of the first Executive office of our country, I avail myself of the presence of that portion of my fellow citizens which is here assembled to express my grateful thanks for the favor with which they have been pleased to look towards me, to declare a sincere consciousness that the task is above my talents, and that I approach it with those anxious and awful presentiments which the greatness of the charge, and the weakness of my powers so justly inspire. A rising nation, spread over a wide and fruitful land, traversing all the seas with the rich productions of their industry, engaged in commerce with nations who feel power and forget right, advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of mortal eye; when I contemplate these transcendent objects, and see the honor, the happiness, and the hopes of this beloved country committed to the issue and the auspices of this day, I shrink from the contemplation & humble myself before the magnitude of the undertaking. Utterly indeed should I despair, did not the presence of many, whom I here see, remind me, that, in the other high authorities provided by our constitution, I shall find resources of wisdom, of virtue, and of zeal, on which to rely under all difficulties. To you, then, gentlemen, who are charged with the sovereign functions of legislation, and to those associated with you, I look with encouragement for that guidance and support which may enable us to steer with safety the vessel in which we are all embarked, amidst the conflicting elements of a troubled world.

During the contest of opinion through which we have passed, the animation of discussions and of exertions has sometimes worn an aspect which might impose on strangers unused to think freely, and to speak and to write what they think; but this being now decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the constitution all will of course arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good. All too will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate would be oppression. Let us then, fellow citizens, unite with one heart and one mind, let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection without which liberty, and even life itself, are but dreary things. And let us reflect that having banished from our land that religious intolerance under which mankind so long bled and suffered, we have yet gained little if we countenance a political intolerance, as despotic, as wicked, and capable of as bitter and bloody persecutions. During the throes and convulsions of the ancient world, during the agonizing spasms of infuriated man, seeking through blood and slaughter his long lost liberty, it was not wonderful that the agitation of the billows should reach even this distant and peaceful shore; that this should be more felt and feared by some and less by others; and should divide opinions as to measures of safety; but every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans: we are all federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union, or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated, where reason is left free to combat it. I know indeed that some honest men fear that a republican government cannot be strong; that this government is not strong enough. But would the honest patriot, in the full tide of successful experiment, abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm, on the theoretic and visionary fear, that this government, the world’s best hope, may, by possibility, want energy to preserve itself? I trust not. I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest government on earth. I believe it the only one, where every man, at the call of the law, would fly to the standard of the law, and would meet invasions of the public order as his own personal concern.—Sometimes it is said that man cannot be trusted with the government of himself. Can he then be trusted with the government of others? Or have we found angels, in the form of kings, to govern him? Let history answer this question.

Let us then, with courage and confidence, pursue our own federal and republican principles; our attachment to union and representative government. Kindly separated by nature and a wide ocean from the exterminating havoc of one quarter of the globe; too high minded to endure the degradations of the others, possessing a chosen country, with room enough for our descendants to the thousandth and thousandth generation, entertaining a due sense of our equal right to the use of our own faculties, to the acquisitions of our own industry, to honor and confidence from our fellow citizens, resulting not from birth, but from our actions and their sense of them, enlightened by a benign religion, professed indeed and practiced in various forms, yet all of them inculcating honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude and the love of man, acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here, and his greater happiness hereafter; with all these blessings, what more is necessary to make us a happy and a prosperous people? Still one thing more, fellow citizens, a wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned. This is the sum of good government; and this is necessary to close the circle of our felicities.

About to enter, fellow citizens, on the exercise of duties which comprehend everything dear and valuable to you, it is proper you should understand what I deem the essential principles of our government, and consequently those which ought to shape its administration. I will compress them within the narrowest compass they will bear, stating the general principle, but not all its limitations.—Equal and exact justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, religious or political:—peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none:—the support of the state governments in all their rights, as the most competent administrations for our domestic concerns, and the surest bulwarks against anti-republican tendencies:—the preservation of the General government in its whole constitutional vigor, as the sheet anchor of our peace at home, and safety abroad: a jealous care of the right of election by the people, a mild and safe corrective of abuses which are lopped by the sword of revolution where peaceable remedies are unprovided:—absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority, the vital principle of republics, from which is no appeal but to force, the vital principle and immediate parent of the despotism:—a well-disciplined militia, our best reliance in peace, and for the first moments of war, till regulars may relieve them:—the supremacy of the civil over the military authority:—economy in the public expense, that labor may be lightly burthened:—the honest payment of our debts and sacred preservation of the public faith:—encouragement of agriculture, and of commerce as its handmaid:—the diffusion of information, and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason:—freedom of religion; freedom of the press; and freedom of person, under the protection of the Habeas Corpus:—and trial by juries impartially selected. These principles form the bright constellation, which has gone before us and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages, and blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment:—they should be the creed of our political faith; the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or of alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps, and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty and safety.

I repair then, fellow citizens, to the post you have assigned me. With experience enough in subordinate offices to have seen the difficulties of this the greatest of all, I have learnt to expect that it will rarely fall to the lot of imperfect man to retire from this station with the reputation, and the favor, which bring him into it. Without pretensions to that high confidence you reposed in our first and greatest revolutionary character, whose pre-eminent services had entitled him to the first place in his country’s love, and destined for him the fairest page in the volume of faithful history, I ask so much confidence only as may give firmness and effect to the legal administration of your affairs. I shall often go wrong through defect of judgment. When right, I shall often be thought wrong by those whose positions will not command a view of the whole ground. I ask your indulgence for my own errors, which will never be intentional; and your support against the errors of others, who may condemn what they would not if seen in all its parts. The approbation implied by your suffrage, is a great consolation to me for the past; and my future solicitude will be, to retain the good opinion of those who have bestowed it in advance, to conciliate that of others by doing them all the good in my power, and to be instrumental to the happiness and freedom of all.

Relying then on the patronage of your good will, I advance with obedience to the work, ready to retire from it whenever you become sensible how much better choices it is in your power to make. And may that infinite power, which rules the destinies of the universe, lead our councils to what is best, and give them a favorable issue for your peace and prosperity.

Recommended Readings

- Jeremy D. Bailey, Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- John B. Boles, Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty (New York: Basic Books, 2017).

- Kevin R.C. Guzman, Thomas Jefferson, Revolutionary: A Radical’s Struggle to Remake America (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017).

- David N. Mayer, The Constitutional Thought of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995).

- Garrett Ward Sheldon, The Political Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993).

- Jean M. Yarbrough, Thomas Jefferson and the Character of a Free People (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998).

Notes

[1] Abraham Lincoln, letter to “Messrs. Henry L. Pierce, & Others,” April 6, 1859, Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/letter-to-henry-pierce-and-others/ (accessed April 29, 2025).

[2] Declaration of Independence, First Draft, Reported Draft, and Engrossed Copy, July 4, 1776, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1904), Vol. II, pp. 199–217, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/755/0054-02_Bk.pdf (accessed March 29, 2025).

[3] Jay Cost, “The Declaration of Independence Was More Radical Than Any of the Men Who Signed It,” National Review, July 2, 2018, https://www.nationalreview.com/2018/07/declaration-of-independence-more-radical-than-its-signers/ (accessed March 29, 2025).

[4] Letter to Henry Lee, May 8, 1825, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1905), Vol. XII, p. 409, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/808/0054-12_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[5] See note 2, supra.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Letter to James Madison, September 6, 1789, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1904), Vol. VI, pp. 3–4, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/803/0054-06_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[8] “From James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, 4 February 1790 [Revised Text],” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-13-02-0020 (accessed March 29, 2025).

[9] Letter to James Madison, January 30, 1787, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1904), Vol. V, p. 256, https//oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/802/0054-05_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[10] Letter to John Adams, October 28, 1813, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1905), Vol. XI, pp. 343–344, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/807/0054-11_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[11] Thomas Jefferson, “Second Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1805, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1905), Vol. X, p. 135, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/806/0054-10_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[12] “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” July 30, 1774, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. II, p. 79.

[13] See note 2, supra.

[14] Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” 1782, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1904), Vol. IV, p. 83, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/756/0054-04_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[15] Thomas Jefferson, “Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank,” February 15, 1791, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. VI, p. 201.

[16] Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on the Constitutionality of Bounties to Encourage Manufacturing, [February 1792],” National Archives, Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-23-02-0161 (accessed March 29, 2025).

[17] See note 15, supra.

[18] Thomas Jefferson, “Memoranda of Conversations with the President, 1 March 1792,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-23-02-0167 (accessed March 29, 2025).

[19] Letter to George Washington, May 23, 1792, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. VI, pp. 490–493.

[20] Thomas Jefferson, “Drafts of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798,” November 1798, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, coll. & ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York & London: Knickerbocker Press, 1904), Vol. VIII, pp. 458–479, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/805/0054-08_Bk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[21] Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 371.

[22] 17 U.S. 316 (1819).

[23] Wilfred M. McClay, Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story (New York: Encounter Books, 2019), p. 41.

[24] Letter to Doctor Benjamin Rush, January 16, 1811, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. XI, p. 168.

[25] “A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom,” in The American Republic: Primary Sources, ed. Bruce Frohnen (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002), pp. 330–331, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/669/0082_LFeBk.pdf (accessed March 30, 2025).

[26] Jefferson, “Second Inaugural Address,” in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. X, p. 131.

[27] Thomas Jefferson, letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, January 1, 1802, in The American Republic: Primary Sources, p. 88.

[28] Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. IV, p. 83.

[29] “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1801, Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/first-inaugural-address-8/ (accessed April 29, 2025).

[30] See note 25, supra.

[31] See note 29, supra.