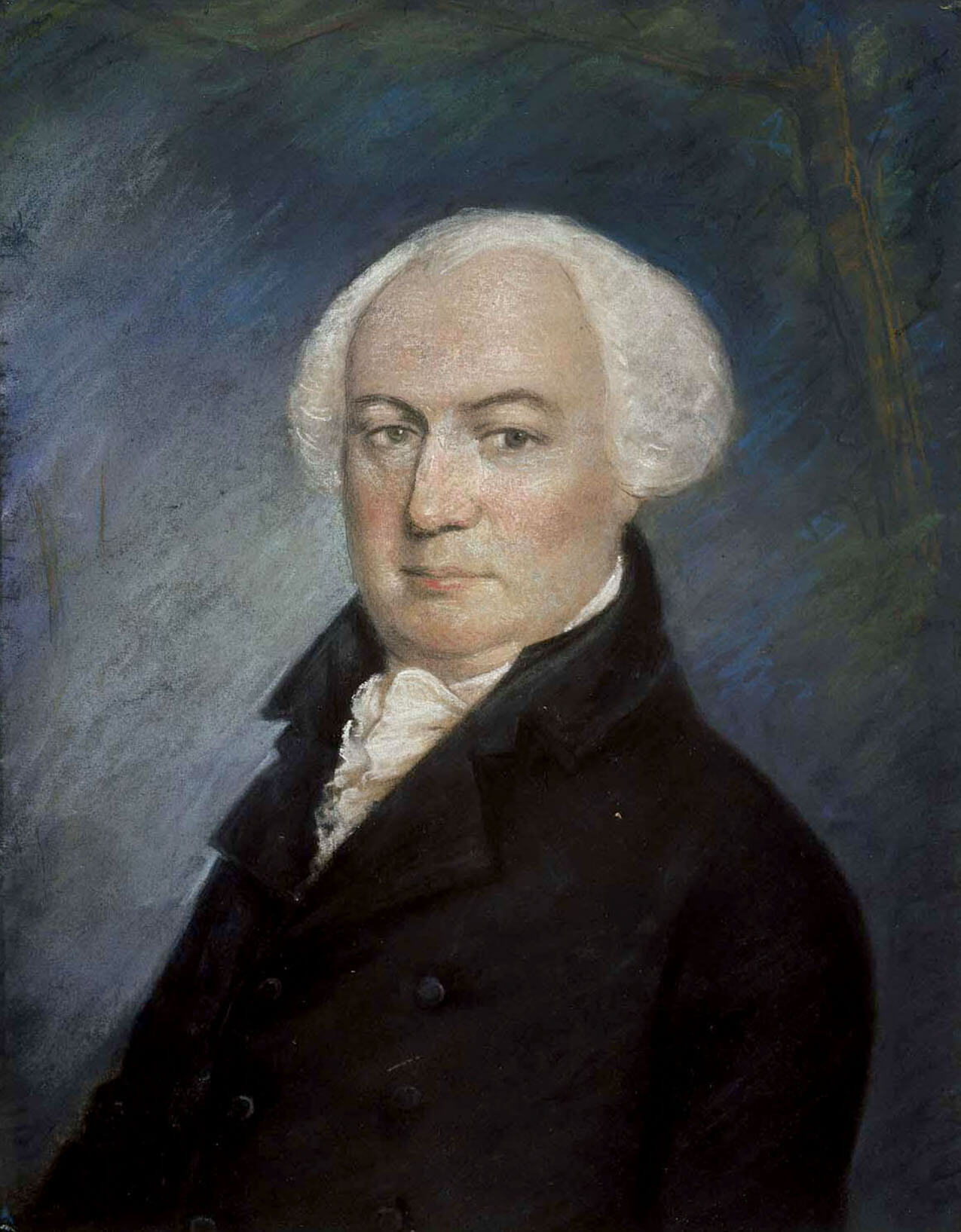

—William Pierce, delegate to the Constitutional Convention from Georgia, 17871

Life

Gouverneur Morris was born January 31, 1752, at Morrisania, the family manor in what is now the Bronx, New York. He was the son of Lewis Morris and Sarah Gouverneur Morris. At age 57, he married Anne Cary (Nancy) Randolph on December 25, 1809; they had one son. Morris died on November 6, 1816, at home in Morrisania.

Education

Rev. Têtard’s academy, New Rochelle; the Academy of Philadelphia; King’s College, BA 1768, MA 1771

Religion

Episcopalian

Political Affiliation

Federalist

Highlights and Accomplishments

1775: First New York Provincial Congress

1776: Third New York Provincial Congress

1777: Continental Congress

1781–1784: Assistant Superintendent of Finance

1787: Constitutional Convention

1792–1794: Minister to France

1801–1803: Senator from New York

1807–1811: Commissioner, New York City Street Commission

1810–1816: President, Erie Canal Commission

Gouverneur Morris is not the best-known of the Founding generation, thanks in part to his own indifference to how he would be remembered. He was convinced that posterity would come to its own conclusions regardless of his generation’s efforts to shape the historical record. Rather than worry about his reputation with later Americans, he set about creating a legacy in public affairs extending from pre-Revolutionary committees of correspondence to the opening of the upper Midwest through the Erie Canal. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress, a member of the U.S. Senate, and U.S. Minister to France through the French Revolution. He was a staunch opponent of slavery, was an equally firm proponent of a vigorous executive, and never doubted that the United States would grow into a world power. He was also witty, sarcastic, and not always aware when his humor had gone too far. He was known or believed to be indiscreet, haughty, and entirely too “fickle and inconstant” to be entirely reliable.2

Morris’s writings reveal a well-educated, shrewd, and consistent perspective on American and world affairs. He began writing for the public as early as 1769 and through his essays and speeches gave voice to a grounded liberalism that emphasized the promise and limits of the human desire for freedom. Believing that too much freedom was as destructive as too little, Morris spent his adult life working to find the happy medium that would permit the full development of the human capacity to live, create, and thrive. Popular government, to be sure, was one way to ensure that balance, but it was not the only way, and Morris thought that Americans who insisted on popular government at the expense of civil rights confused means and ends. Posterity’s neglect of Morris may stem as much from his sober view of the prospects for liberalism—humans can have free government, but they need to overcome their human frailties to be successful—as from his indifference to their judgment.

The Life of Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris was born January 31, 1752, in what is now the Bronx, New York. His family had been prominent in colonial affairs; his grandfather had been governor of New Jersey, and his father was an Admiralty judge and speaker of the New York Assembly. Gouverneur was the only son from his father’s second marriage to Sarah Gouverneur; he had three older half-brothers: Lewis Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence; Staats Long, who became a general in the British Army; and Richard, who became a New York judge. The three older brothers attended Yale College, but their father was unhappy with the education they received and sent Gouverneur to King’s College (now Columbia University) instead. He received his bachelor’s degree in 1768, and a master’s degree in 1771 when he was 19. The orations he gave at both commencements have been preserved.

After college, Morris read law in the office of William Smith, a prominent New York attorney, along with two other aspiring lawyers, John Jay and Robert Livingston. The three became lifelong friends. By this time, the movement toward American independence was well in motion. Morris was on the Westchester County Committee of Safety and was elected a delegate to the First and Third Provincial Congresses. He, Jay, and Livingston were the primary authors of the New York Constitution of 1777, and in early 1778, he went to the Continental Congress, then meeting in York, Pennsylvania.

Appointed to a committee charged with seeing to the condition of the Continental Army, he went to Valley Forge almost immediately to carry out his duty. There he met George Washington again, an encounter that deepened his sincere admiration for the general. Returning to York, Morris threw himself into the work of Congress and for the rest of that year authored many reports and public letters supporting the American cause. Because he favored continental interests over New York’s interests, he was not reappointed in 1779. He chose to stay in Philadelphia to work as an attorney and businessman because his home in New York was occupied by the British.

For the next several years, he lived and worked in Philadelphia and became increasingly involved with the far-flung business interests of Robert Morris (who was not related to him). When Robert Morris was appointed Superintendent of Finance in 1781, he asked Gouverneur to serve as his assistant, to which Gouverneur agreed. Later, when Robert Morris was selected as a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he urged the legislature to add Gouverneur to the list of delegates, which (somewhat to Gouverneur’s surprise) they did.

Although he missed more than a month of the Convention’s deliberations, he eventually spoke more than any other delegate and provided the final wording of the Constitution. He also completely rewrote the Preamble, giving it its majestic opening phrase, “We the People of the United States.” The clear and elegant way Morris laid out the separated powers under the Constitution was unusual for the day. At that time, most state constitutions, like the draft of the Committee of Style, mixed provisions with little attention to strict separation. Morris’s clear delineation of the separation of powers in the Constitution’s first three articles has affected American thinking about the issue ever since then.

Persistent rumors have circulated that Morris was in some way dishonest as the Constitution’s penman and subtly worked to transform selected clauses in a more nationalist direction. James Madison, although by then a political adversary, later defended Morris against those charges.

In 1789, Morris went to Europe to help restore his and Robert Morris’s business interests. He also carried out some confidential missions for President Washington in Britain. He was accused (probably by Alexander Hamilton who, despite this, remained a good friend) of having revealed his mission to the French. Washington overlooked the charge and appointed him to succeed Thomas Jefferson as Minister to France. In his letter informing Gouverneur Morris of his appointment, Washington offered a frank assessment of his character:

I will place the ideas of your political adversaries in the light which their arguments have brought them to my view, viz. that tho’ your imagination is brilliant the promptitude with which it is displayed allows too little time for deliberation or correction, and is the primary cause of those sallies which too often offend, and of that indiscreet treatment of characters…which might be avoided if they were under the guidance of more caution and prudence….3

From 1792 to 1794, he carried out this challenging assignment, at times as the only foreign representative in Paris, through the political twists and turns of the French Revolution.

When he arrived in France, Morris started a diary, which remains one of our best sources for the day-to-day progress of the French Revolution. It recounts quite intimate details of such things as his advice to the king, his assistance (financial and otherwise) to French aristocrats, and his loans and gifts of money to those who were caught up in the Revolutionary turmoil—as well as his active love life. He also helped to look after the interests of American citizens, or those such as Thomas Paine who had (or made) claims to American protection. By 1794, the newest French government was controlled by his enemies, and Morris was recalled, partly as a tit-for-tat response to the recall of Citizen Genêt. In October, he left France but stayed in Europe for the next four years, visiting exiled French friends, meeting with royalty, passing on and receiving intelligence on the political and military situation in Europe, and seeing the sights like any other tourist.

Morris finally left Hamburg in October 1798 after a European sojourn of more than a decade. Once home, he set about putting his Morrisania estate in order after a decade of British occupation and neglect and settled into the life of a local magnate. His business activities flourished, and his land speculations led him to travel extensively. Meanwhile, his political interests led to an extensive correspondence and frequent essays for the New York press. In April 1800, the New York legislature appointed him to fill the U.S. Senate seat vacated by James Watson. He was present through the multi-ballot election of Jefferson as President and later for Jeffersonian attempts to reverse the effects of the Adams Administration.

We have a number of Senate speeches from Morris, including his opposition to repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801. Although Morris and Jefferson were cordial to one another, they were aware that as political adversaries they would not see eye to eye. The exception to this was the Louisiana Purchase, which other Federalists opposed but Morris thought was a welcome development. In his view, opening the West would provide a counterweight to the southern slaveholding states in American politics. By 1806, when Jefferson introduced the Non-Importation Act, and 1807, when it escalated into an embargo, popular sentiment supported the Administration in its attempts to assert American power. Morris disagreed with those assessments and saw the Jeffersonian hostility to England and, more important, to a commercial economy as a destructive force.

When he was in the Senate, Morris had viewed repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 and passage of the 11th Amendment as harbingers of the Constitution’s demise. Eliminating good behavior–tenured judges made Congress practically omnipotent, for it meant no part of the Constitution could be exempt from the majority’s will. Likewise, the increase of state power—the stubborn insistence on the separate and inviolable sovereignty of state governments—meant that the United States remained short of being a nation.

Morris’s forebodings about the future of the American government ultimately led to his cautious support of the Hartford Convention. Morris did not share his biographer Theodore Roosevelt’s consternation at this movement, for it was his settled belief that the Constitution was not a work of genius, but rather the labor of “plain, honest men.” He did not believe it would or should be permanent because he did not believe it was the best that could be devised. As the Constitution’s penman, Morris had given the document its distinctive language and unmistakable logic, but he believed that better proposals would be available at some future date. If the Hartford Convention forced some issues to the table or—worse—should lead to a breakup of the current Union, Morris thought that either might be better than the existing hegemony of the Republican party.

In 1808, Morris became reacquainted with Anne Cary Randolph, known as Nancy, whom he had met 20 years earlier when she was about 14. Nancy was a member of Virginia’s prominent Randolph family but had been driven away following a lurid scandal in 1792. By 1808, she was in New York and penniless. Morris proposed that she should become his housekeeper, and she accepted in April 1809. They were married on Christmas Day 1809, as Gouverneur noted in his diary: “I marry this day Anne Cary Randolph—No small surprise to my guests.”4 The match proved to be a good one. Their son, also named Gouverneur, was born in 1813, and Nancy devoted the rest of her life to raising and educating him.

In his retirement, Morris took on two more public activities. In 1807, he joined with Simeon DeWitt, a surveyor, and John Rutherfurd to plan the growth of New York City. In 1811, the Commissioners produced the regular street design of rectangular blocks we know today. In 1810, Morris accepted a seat on the Erie Canal Commission and was elected president, although the real driver of the Commission was DeWitt Clinton, soon to become governor of New York. With the federal government having declined to fund the project, New York decided to fund the canal itself, and it was duly completed in 1825, nine years after Morris died. Morris’s last years were troubled by illness and his nephew’s debts, but by all accounts, he seems to have had a serene retirement, confident that he had done his best.

Public Finance

It is difficult for modern readers to appreciate how different “political economy” appeared in the last quarter of the 18th century. The first book on the subject, Sir James Steuart’s An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy, was published in 1767, and we know that Gouverneur Morris read it at Robert Morris’s suggestion. Steuart was a moderate mercantilist, and British policy until the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 generally reflected mercantilist thinking. When Adam Smith’s 1776 An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations questioned mercantilist principles, it was not immediately accepted, as it defied conventional thinking about free trade. His experience with government finance in the 1780s led Morris to agree with Smith on free trade. Trade, credit, paper money, and property rights dominated Morris’s activity and writing at this low point in American public finance.

The prevailing mode of business organization at the time was the partnership; the business corporation, with its perpetual life, limited liability, and freedom to acquire unlimited amounts of capital, simply did not exist then. A New York statute passed in 1811 allowed incorporation for manufacturing only. It was not until 1837 that Connecticut law allowed incorporation for any corporation engaged in lawful business. In other words, business in Morris’s day was much more personal and depended far more on the reputation and connections of the business owners. Loans and bankruptcy were personal, not organizational. In an atmosphere that depended on reputation and trust, business depended on the character of those who were engaged in it. For these reasons, Morris thought, rights and property had to be strictly respected because that meant respecting people’s rights to create, produce, and retain the fruits of their efforts.

In early 1780, Morris wrote a series of essays for the Pennsylvania Packet that explored a number of financial themes, including paper money. In these essays, he changed his earlier position and argued that paper money could be made solid and reliable provided it “were emitted in such a form that it could not be well counterfeited, under such circumstances that it would not depreciate, and for sums not expressed by any particular coin.”5 Even though wartime depreciation of United States currency had been severe, Morris had come to believe that new issues of paper could be sufficiently well managed to serve the purpose.

The point, which had been key since 1776 and would remain so until 1790, was that the federal government needed revenue to back its currency as well as to pay its debts. Whether immediate needs were met through foreign or domestic loans, no one would be willing to extend credit to a government that had no ability to repay them. It was as simple as that. Congress eventually agreed to an impost and sent it to the states for approval, but it failed. In the meantime, Robert Morris used his personal credit to support that of the United States. In 1781, he began to issue “Morris Notes”—bills drawn on his own account that effectively became a national currency.6

Among the papers Gouverneur Morris produced while Assistant Superintendent of Finance were letters and a draft of a paper to the French Minister to the U.S., the Chevalier de la Luzerne, in 1783 on trade with the French islands in the Caribbean. Morris discussed trade between the U.S. and the islands within the larger context of trade between the U.S. and France. He made the case for light regulation and advocated something very much like free trade. Morris’s point was that French mercantilist policies were simply ineffective in producing the results they were intended to deliver. French ships would be employed in the trade whether or not American ships were also used, and the increase of trade would increase the number of French vessels and seamen. “The Benefits,” he concluded, “in a Commercial Point of View will be reciprocal.”7 These writings on trade became the basis of French policy in an Arrêt of August 1784 and convinced French policymakers and intellectuals that they reflected Enlightenment ideas. They were the foundation of Morris’s reputation in France as a statesman who could write constitutions and also understand finance and trade.

The Executive Power

Americans’ knowledge of executive power was derived from the British king and their former colonial governors. As a result, Americans commonly thought of severe checks on executive power as the one necessary ingredient of popular government. Morris argued very early on that an effective government needs a strong executive. He knew that liberty needed to be checked so that property rights and other civil liberties could be protected. This meant restricting everyone’s natural freedom for the sake of protecting civil freedom. All of these things demanded an executive power that was able to make and enforce decisions. Morris said that if he were to choose a master, he would prefer “a single Tyrant, because I had infinitely rather be torn by a Lion than eaten by Vermin.”8 If such a strong executive risked tyranny, then so be it.

In his view, the key to controlling executive power was not to divide it but to make it transparent. Thus, the New York Constitution of 1777 provided for the strongest executive with the longest term—three years—in the new American states. Although Morris would have secured a qualified veto and an independent appointing power for the governor, the New York convention would not go that far and instead adopted alternative proposals for a council of revision and a council of appointment.9

Morris thought that the executive should be a figure closely identified with the people. As he said during the Constitutional Convention, the people needed to be able to judge the executive’s actions and to have enough time to evaluate the effects of a series of measures. A single-year term, the norm in most states, was simply not enough time for the people to weigh a governor’s impact. In balancing the powers within the government, it was necessary first to equalize them. An executive needed to be as powerful as the legislature, for there could be no other check on bad laws. The press could be helpful, but the press alone would not be sufficient to check an overbearing legislature.10

It is important to note that by “strong” he did not mean a monarch as his friend Alexander Hamilton had advocated. Morris thought a monarchy was too independent of the people to provide good government. He also thought that an executive elected by the legislature would be too dependent on the legislative branch. His solution was a popularly elected executive with a term that was long enough for people to see and feel the effects of his policies. Against the idea that the country was simply too large for the people to have relevant information, Morris countered that this had not been the case in New York. While it was true that in certain spots “designing men” had misled the people into voting in particular ways, “the general voice of the State is never influenced by such artifices.”11 Moreover, the legislature could conceal its machinations more easily than the people could. The people might be misled or seduced in favor of a candidate—a danger inherent in any democratic system—but they would not be the authors of a conspiracy.

For Morris, a strong executive was imperative to control the likely effort of the rich to establish an aristocracy on the ruins of American democracy. He pointed out that the “Rich will strive to establish their dominion & enslave the rest. They always did. They always will.”12 He was concerned in particular that the wealthy classes would use their influence to control the legislature: “[Mr. Govr. Morris] fears the influence of the rich. They will have the same effect here as elsewhere if we do not by such a Govt. keep them within their proper sphere.” He further warned that “the people never act from reason alone. The rich will take advantage of their passions and make these the instruments for oppressing them.”13

Tying the executive to the people through popular election and providing powerful tools such as the veto power would enable the executive to control the pernicious tendencies of the wealthy.

Liberty and the Rule of Law

Unlike his friend Alexander Hamilton, who admired the form of the British Constitution, Morris appreciated its results. In his estimation, Britain had achieved free government—whether because of or in spite of its form—by adhering to the rule of law and strictly respecting property rights. The end of securing liberty was more important to Morris than the form of government by which it was secured. In the early days of the Revolution, he spent some time thinking through the practical meaning of liberty in its various forms—natural, political, and civil.14 His conclusion was that civil liberty is the essential goal of a free society. This right to property and personal freedom, however, can be preserved only by restricting political liberty—the right to choose the laws under which one lives. When society is organized, political liberty is progressively checked as rules are chosen. Once made, for the sake of protecting the property and civil rights of the people, those choices should not be easily changed.

Morris agreed with Locke that the security of property is the reason people choose to have government in the first place, but recognizing rights to property requires curtailing the liberty of people to change the rules of ownership or enjoyment. Civil liberty and political liberty together form a simple scale: The more of one, the less of the other. “If we consider political in Connection with civil Liberty we place the former as the Guard and Security to the latter. But if the latter is given up for the former we sacrifice the End to the Means.”15 Morris believed that Britain had found the right balance between political and civil liberty, and he worked to provide the same balance for Americans.

Any balance between them, however, was upset by slavery. In Morris’s understanding, slavery destroyed the possibility of balance: Slaveholders had the political liberty to deny basic human rights to others and the civil liberty to treat other human beings as property. All the rights were on one side, and no neutral judgment of a magistrate could intervene. It was a clear contradiction of American principles, as Morris said at the Constitutional Convention:

Mr Govr. Morris…never would concur in upholding domestic slavery. It was a nefarious institution—It was the curse of heaven on the States where it prevailed.… [A]dmission of slaves into the Representation…comes to this: that the inhabitant of Georgia and S.C. who goes to the Coast of Africa, and in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections & damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes in a Govt. instituted for protection of the rights of mankind, than a Citizen of Pa or N. Jersey who views with a laudable horror, so nefarious a practice.16

Morris saw free government in the United States as threatened by slavery, which furnished a telling example of how self-interest could blind men to the reality of their own institutions and principles. This was as clear an illustration as one might find of the danger of maximizing political freedom. A government resting on popular choice risked legitimizing choices made when the people were not thinking clearly, perhaps in a fearful or selfish mood. Finding the right way to minimize these irrational choices would be key to establishing a stable and free government.

Morris had no great faith in forms and believed that any form of government would be strongest if it grew naturally out of the materials society furnished. He thought that in the United States, the strongest materials would be found from the “Spirit of Commerce.” This spirit would lead American society to respect civil liberty, property rights, and the rule of law. Commerce was an outlet for people’s sense of self-interest, but it was also more. It produced “the most rapid Advances in the State of Society” because “once begun [it] is from its own Nature progressive.”17 It also helped to keep a check on political liberty: “Now as Society is in itself Progressive as Commerce gives a mighty Spring to that progressive force as the effects both joint and Separate are to diminish political Liberty. And as Commerce cannot be stationary the society without it may.”18 Finally, “If a Medium be sought it will occasion a Contest between the spirit of Commerce and that of the Government till Commerce is ruined or Liberty destroyed. Perhaps both.”19

Many years later, Morris saw this dynamic in play as the Jefferson and Madison Administrations worked to hobble American commerce. He considered American civil liberty in jeopardy from the hostility to commerce that arose from Jefferson’s favoring of the people’s political liberty. Thus, Jefferson’s Administration marked the decline of the most secure check on the enemies of property rights and civil liberties.

Morris drew a link between the goal of politics—securing property rights—and civil liberty, which allows property to be freely enjoyed. Commerce, he thought, is the thread that commits society both to respect property rights and to moderate the extremes of popular passions. As long as the United States remained a commercial society, there would be powerful social forces that favored the rule of law and protection of property rights.

The Skeptical Democrat

Morris took a detached and amused view of human nature and human beings. It was easy for humans to be misled or confused, especially when personal self-interest encouraged that confusion. People could not always see their best interests, and this blindness was multiplied as the number of actors increased. Democracy, Morris believed, was just as likely to multiply human blindness as it was to enhance human enlightenment.

For this reason, any human institution has a limited life, because every generation brings new and different experiences into play and will make new and different mistakes. This, again, is a constraint imposed by human understanding. We expect tomorrow to be like yesterday, and change upsets and confuses this expectation. The problem is that change, both in the world and in ourselves, is continuous, and our understanding is therefore always struggling to catch up with it. Morris looked upon this human shortcoming with amused tolerance:

Philosophy…may…deduce fair-seeming conclusions from an assumed principle that man is a rational creature. But is that assumption just? Or, rather, does not History show, and experience prove, that he is swayed from the course which reason indicates, by passion, by indolence, and even by caprice?… Such [philosophic] writings, therefore…instead of showing man a just image of what he is, will frequently exhibit the delusive semblance of what he is not.20

In other words, the hardest thing for man to see objectively is man.

Although a reluctant democrat—“In adopting a republican form of government, I not only took it as a man does his wife, for better, for worse, but, what few men do with their wives, I took it knowing all its bad qualities”21—Morris continued to believe (with qualifications) that democracy was the best form for the United States. He understood that people would think what they think regardless of moral or logical restraints and therefore never tried to edit his papers or create institutions that would preserve his legacy. The future would take care of itself without regard to what we might think of ourselves:

He, who looks far forward into probabilities, possessing tolerable knowledge of that motley composition, man, may form a few just expectations of events. If wise, he will confine his conjectures to his own bosom, or entrust them only to the bosom of confidential friendship. The vulgar, great and small, cannot bear truth. It shocks some, frightens many, and pleases few or none. Believe this, however[;] nations acquire the form of government most fit for them….

History had long since told us the tale of Democracy.… I consider it a vain task to preach to unbelievers. They are to be converted only by suffering. They must be schooled with adversity, where their false friends are their teachers. After some smart correction, they may be more manageable, and then, but not before, it may be prudent to attempt such changes in our social organization, as may save us from despotism….22

Deeds rather than words would convince the people. In simpler terms, “the good we hope is seldom obtained, and the evil we fear is rarely realized.”23 To err, as Pope had said, is the human lot, and a government that maximizes human liberty will maximize the other human qualities—good and bad—as well.

One might characterize Gouverneur Morris as a rich dilettante, pursuing his own interests without regard to any steady pursuit of a definable career, but the riches came late. Morris had to make his own fortune and therefore held many positions during his life, but he never held one position for long and consistently retreated into his private enterprises. He was a bachelor (and rather a swinging one) until he was 57, but then he was a serious and faithful husband. He composed light verse—doggerel—for the ladies but was also a serious wordsmith to whom people turned when they needed the best penman. He declined only one public assignment— Hamilton’s invitation to contribute to The Federalist—but to the end advised the public through the press. In the words of Theodore Roosevelt, his 19th century biographer:

Perhaps his greatest interest for us lies in the fact that he was a shrewder, more far-seeing observer and recorder of contemporary men and events, both at home and abroad, than any other American or foreign statesman of his time.… He made the final draft of the United States Constitution; he first outlined our present system of national coinage; he originated and got under way the plan for the Erie Canal; as minister to France he successfully performed the most difficult task ever allotted to an American representative at a foreign capital. With all his faults, there are few men of his generation to whom the country owes more than to Gouverneur Morris.24

Selected Primary Writing

“Political Enquiries” (1776)25

Of the Object of Government

Is it the legitimate Object of Government to accumulate royal Magnificence, to maintain aristocratic Pre-Eminence, or extend national Dominion? The answer presents itself: Is it then the public Good? Let us reflect before we reply. Men may differ in their Ideas of public Good. Rulers therefore may be mistaken. In the sincere Desire to promote it just Men may be proscribed, unjust Wars declared, Property be invaded & violence patronized. Alas! How often has public Good been made the Pretext to Atrocity! How often has the Maxim Salus populi suprema Lex esto,26 been written in Blood!

Suppose a man about to become the Citizen of another State and bargaining for the Terms. What would be his Motive? Surely the Encrease of his own felicity. Hence he would reject every Condition incompatible with that Object, and exact for its Security every Stipulation. Propose to him that when Government might think proper he should be immolated for the public Good: would he agree? To ascertain that Compact which in all Societies is implied, we must discover that which each Individual would express. The Object of Government then is to provide the Happiness of the People.

But are Governments ordained of God? I dare not answer. If they are, they must have been intended for the Happiness of Mankind. Hence an important Lesson to those who are charged with the Rule of Men.

Of Human Happiness

We need not enquire whether mortal Beings are capable of absolute felicity; but it is important to know by what means they may obtain the greatest Portion which is compatible with their State of Existence. Three questions arise: What constitutes the Happiness of a Man, of a State, of the World? The same Answer applies to each. Virtue. Obedience to the moral Law. Of avoidable Evil, there would be less in the World if the Conduct of States towards each other was regulated by Justice; there would be less in Society if each Individual did to others what he would wish from them; and less would fall to every Man’s Lott if he were calm temperate and humane. To inculcate Obedience to the moral Law is therefore the best means of promoting human Happiness. Hence a maxim. No Government can lawfully command what is wrong. Hence also an important Reflection. If Government dispenses with the Rules of Justice, it impairs the Object for which it was ordained.

But how shall Obedience to the moral Law be inculcated? By Education Manners Example & Laws. Hence it follows that Government should watch over the Education of Youth. That Honor and Authority should not be conferred on vicious Men. That those entrusted with office should not only be virtuous but appear so. And that the Laws should compel the Performance of Contracts, give Redress for Injuries, and punish Crimes.

Of Public Virtue

Which should be most encouraged by a wise Government public or private Virtue? Another question immediately arises. Can there be any Difference between them? In other Words, can the same thing be right and wrong? If an Action be in its own Nature wrong, we can never justify it from a Relation to the public Interest but by the Motive of the Actor. & who can know his Motive? From what Principle of the human Heart is public Virtue derived? Benevolence knows not any Distinctions of Nation or Country. Perhaps if the most brilliant Instances of roman Virtue were brought to the ordeal of Reason, they would fly off in the light Vapor of Vanity.

A Man expends his fortune in political Pursuits. Was he influenced by the Desire of personal Consideration, or by that of doing Good? If the latter, has Good been effected which would not have been otherwise produced? If it has, was he justifiable in sacrificing to it the Subsistence of his Family? These are important questions; but there remains one more. Would not as much Good have followed from an industrious attention to his own Affairs? A Nation of Politicians, neglecting their own Business for that of the State, would be the most weak miserable and contemptible Nation on Earth. But that Nation in which every Man does his own Duty, must enjoy the greatest possible Degree of public and private Felicity.

Of Political Liberty

Political Liberty is defined, the right of assenting to or dissenting from every Public Act by which a Man is to be bound. Hence, the perfect enjoyment of it presupposes a Society in which unanimous Consent is required to every public Act. It is less perfect where the Majority govern. Still less where the Power is in a representative Body. Still less where either the executive or judicial is not elected. Still less where only the legislative is elected. Still less where a Part of the Representatives can decide. Still less where such Part is not a Majority of the whole. Still less where the Decisions of such Majority may be delayed or overruled. Thus the Shades grow weaker and weaker, till no Trace remains. But is it not destroyed by the first Restriction?

In England, a Majority of Citizens does not elect the Majority of Representatives. A certain Part of those Representatives being met, the Majority of them can bind the Electors. The Decisions of these Representatives are confined to the legislative Department. And the Dissent of the Lords or of the King sets aside what the Commons had determined. The Englishman therefore does not, in any degree, possess the Right of dissenting from Acts by which he is affected, so far as those Acts relate to the Executive or judicial Department. And in respect to the legislature, his political Liberty consists in the Chance that certain Persons will not consent to Acts which he would not have approved. And is that a Right which, depending on a Complication of Chances, gives one thousand against him for one in his favor? Right is not only independent of, but excludes the Idea of Chance.

Of Society

Of these three things Life Liberty Property the first can be enjoyed as well without the Aid of society as with it. The second better. We must therefore seek in the third for the Cause of Society. Without Society Property in Goods is extremely precarious. There is not even the Idea of Property in Lands. Conventions to defend each others Goods naturally apply to the Defence of those Places where the Goods are deposited. The Object of such Conventions must be to preserve for each his own share. It follows therefore that Property is the principal Cause & Object of Society.

Of the Progress of Society

Property in goods is the first step in Progression from a State of Nature to that of Society. Till property in lands be admitted Society continues rude and barbarous. After the lands are divided a long space intervenes before perfect Civilization is effected. The Progress will be accelerated or retarded in Proportion as the administration of justice is more or less exact. Here then are three distinct kinds of Society: 1. rude and which must continue so. 2. progressive towards Civilization. 3. Civilized. For Instances of each take:

1. The Tartar Hords & American Savages. 2. The History of any European Kingdom before the sixteenth century and the present State of Poland. 3ly. the actual Circumstances of France and England.

If the forgoing reflections be just this Conclusion results that the State of Society is perfected in Proportion as the Rights of Property are secured.

Of Natural Liberty

Natural Liberty absolutely excludes the Idea of political Liberty since it implies in every Man the Right to do what he pleases. So long, therefore, as it exists Society cannot be established and when Society is established natural Liberty must cease. It must be restricted. But Liberty restricted is no longer the same. He who wishes to enjoy natural Rights must establish himself where natural Rights are admitted. He must live alone.

If he prefers Society the utmost Liberty he can enjoy is political. Is there a Society in which this political Liberty is perfect? Shall it be said that Poland is that Society? It must first be admitted that nine tenths of the Nation (the Serfs) are not Men. But dignify the Nobles with an exclusive title to the Rank of Humanity and then examine their Liberum Veto.27 By this it is in the Power of a single Dissent to prevent a Resolution. Unanimity therefore being required no Man is bound but by his own Consent at least no noble man. If it be the Question to enact a law this is well. But suppose the Reverse. Or suppose the public Defence at Stake. In both Cases the Majority are bound by the minority or even by one. This then is not political Liberty.

Progress of Society. The Effect on Political Liberty

We find then that perfect political liberty is a Contradiction in Terms. The Limitation is essential to its existence. Like natural Liberty it is a Theory. A has the natural Right to do as he pleases. So has B. A in consequence of his natural Right binds B to an oak. If it be said that Each is to use his right so as not to injure that of another we come at once within the Pale of civil or social Right.

That Degree of political Liberty essential to one State of Society is incompatible with another. The Mohawks or Oneidas may assemble together & decide by the Majority of Votes. The six Nations must decide by a Majority of the Sachems.28 In a numerous Society Representation must be substituted for a general assemblage. But arts produce a Change as essential as Population. In order that government decide properly it must understand the Subject. The objects of legislation are in a rude Society simple in a more advanced State complex. Of two things therefore one. Either Society must stop in its Progression for the Purpose of preserving political Liberty or the latter must be checked that the former may proceed.

Where political Liberty is in excess Property must always be insecure and where Property is not secure Society cannot advance. Suppose a state governed by Representatives equally & annually chosen of which the Majority to govern. Either the Laws would be so arbitrary & fluctuating as to destroy Property or Property would so influence the Legislature as to destroy Liberty. Between these two Extremes Anarchy.

Of Commerce

The most rapid Advances in the State of Society are produced by Commerce. Is it a Blessing or a Curse? Before this Question be decided let the present and former State of commercial Countries be compared. Commerce once begun is from its own Nature progressive. It may be impeded or destroyed not fixed. It requires not only the perfect Security of Property but perfect good faith. Hence its Effects are to encrease civil and diminish political Liberty. If the public be in Debt to an Individual political Liberty enables a Majority to cancel the Obligation but the spirit of Commerce exacts punctual Payment. In a Despotism everything must bend to the Prince. He can seize the Property of his Subject but the Spirit of Commerce requires that Property be secured. It requires also that every Citizen have the Right freely to use his Property.

Now as Society is in itself Progressive as Commerce gives a mighty Spring to that progressive force as the effects both joint and Separate are to diminish political Liberty. And as Commerce cannot be stationary the society without it may. It follows that political Liberty must be restrained or Commerce prohibited. If a Medium be sought it will occasion a Contest between the spirit of Commerce and that of the Government till Commerce is ruined or Liberty destroyed. Perhaps both. These Reflections are justified by the different Italian Republics.

Civil Liberty in Connection with Political

Political Liberty considered separately from civil Liberty can have no other Effect than to gratify Pride. That society governs itself is a pleasing reflection to Members at their Ease but will it console him whose Property is confiscated by an unjust Law? A Majority influenced by the Heat of party spirit banishes a virtuous Man and takes his Effects. Is Poverty or is Exile less bitter decreed by a thousand than inflicted by one? Examine that Majority. In the Madness of Victory are they free from apprehension? What happens this day to the Victim of their Rage may it not happen tomorrow to his Persecutors?

If we consider political in Connection with civil Liberty we place the former as the Guard and Security to the latter. But if the latter is given up for the former we sacrifice the End to the Means. We have seen that the Progress of Society tends to Encrease civil and diminish political Liberty. We shall find on Reflection that civil Liberty itself restricts political. Every Right of the Subject with Respect to the Government must derogate from its Authority or be thereby destroyed. The Authority of Magistrates is taken from that mass of Power which in rude Societies and unballanced Democracies is wielded by the Majority. Every Separation of the Executive and judicial Authority from the Legislative is a Diminution of political and Encrease of civil Liberty. Every Check and Ballance of that Legislature has a like Effect and yet by these Means alone can political Liberty itself be secured. Its Excess becomes its Destruction.

In looking back we shall be struck with the following Progression Happiness the Object of Government. Virtue the Source of Happiness. Civil Liberty the Guardian of Virtue political liberty the Defence of civil. Restrictions on political Liberty the only Means of preserving it.

Recommended Readings

- Mary-Jo Kline, Gouverneur Morris and the New Nation, 1775–1788 (New York: Arno Press, 1978).

- Jared Sparks, The Life of Gouverneur Morris, With Selections from his Correspondence, and Miscellaneous Papers (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1832).

- J. Jackson Barlow, ed., To Secure the Blessings of Liberty: Selected Writings of Gouverneur Morris (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2012).

- Donald L. Robinson, “Gouverneur Morris and the Design of the American Presidency,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Spring 1987), pp. 319–328, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40024718.

- Max M. Mintz, Gouverneur Morris and the American Revolution (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970).

Notes

[1] “William Pierce: Character Sketches of Delegates to the Federal Convention,” in The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, ed. Max Farrand (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1911), Vol. III, p. 92, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1787/0544-03_Bk.pdf (accessed April 14, 2025) (hereinafter Records).

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Enclosure: George Washington to Gouverneur Morris, 28 January 1792,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-23-02-0081 (accessed April 28, 2025).

[4] The Diary and Letters of Gouverneur Morris, ed. Ann Cary Morris (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1888), Vol. II, p. 516, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1170/0215-02_Bk.pdf (accessed May 1, 2025).

[5] An American [Gouverneur Morris], “To the Inhabitants of America,” Pennsylvania Packet, or Advertiser, February 17, 1780, in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty: Selected Writings of Gouverneur Morris, ed. J. Jackson Barlow (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2012), p. 107, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/2623/Morris_SelectedWritings1611_LFeBk.pdf (accessed April 14, 2025).

[6] Mary-Jo Kline, Gouverneur Morris and the New Nation, 1775–1788 (New York: Arno Press, 1978), p. 198.

[7] Gouverneur Morris, “Ideas of an American on the Commerce Between the United States and French Islands As It May Respect Both France and America (1783),” in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty, p. 182.

[8] Gouverneur Morris, “Oration on the Necessity for Declaring Independence from Britain (1776),” in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty, p. 21.

[9] Max M. Mintz, Gouverneur Morris and the American Revolution (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), pp. 74–76.

[10] Farrand, Records, Vol. II, p. 76; Donald L. Robinson, “Gouverneur Morris and the Design of the American Presidency,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Spring 1987), pp. 323–324, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40574454.

[11] Farrand, Records, Vol. II, pp. 30–31.

[12] Farrand, Records, Vol. I, p. 512.

[13] Ibid., p. 514.

[14] Gouverneur Morris, “Political Enquiries (1776),” in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty, pp. 5–11.

[15] Ibid., p. 11.

[16] Farrand, Records, Vol. II, p. 222.

[17] Morris, “Of Commerce,” in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty, p. 10.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., p. 11.

[20] Gouverneur Morris, “An Inaugural Discourse (1816),” in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty, p. 642.

[21] Anne Cary Morris, ed., The Diary and Letters of Gouverneur Morris (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1888), Vol. II, pp. 436, 451–452.

[22] Letter to Jonathan Mason, April 11, 1809, in Jared Sparks, The Life of Gouverneur Morris, With Selections from his Correspondence, and Miscellaneous Papers (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1832), Vol. III, p. 251.

[23] Letter to Henry W. Livingston, November 25, 1803, in ibid., p. 186.

[24] Theodore Roosevelt, American Statesmen: Gouverneur Morris (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1892), p. 364.

[25] Morris, “Political Enquiries (1776),” in To Secure the Blessings of Liberty, pp. 5–11.

[26] “The safety of the people should be the supreme law.” [Barlow editorial note.]

[27] Literally, “I freely forbid it.” Morris reflects the generally held Anglo–American understanding that the liberum veto meant that unanimous consent of the members was required to every act of the Polish Sejm (Parliament). [Barlow editorial note.]

[28] Representatives of the Six Nations to the common council. [Barlow editorial note]