—Representative Henry Lee, December 26, 17991

Life

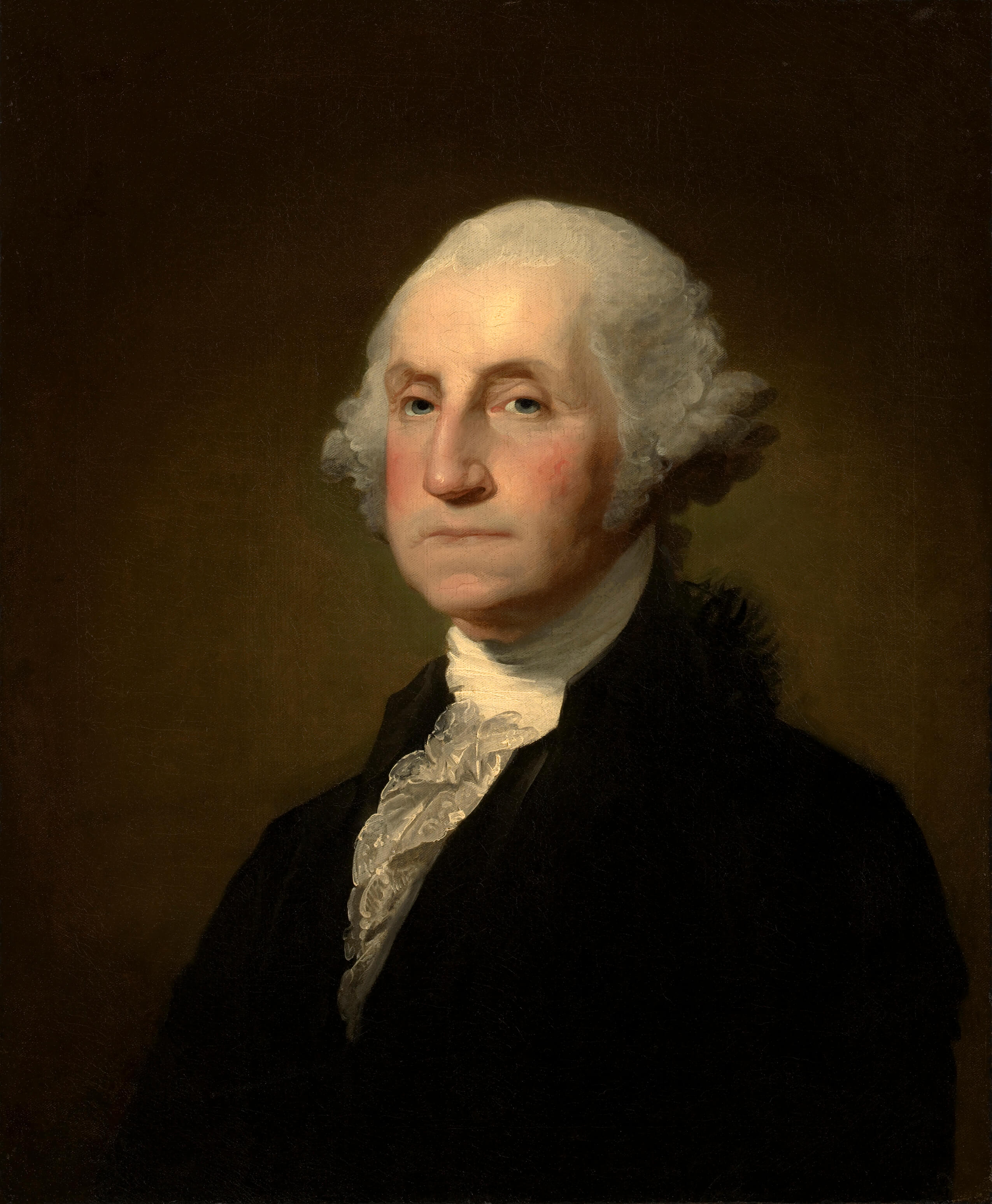

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, near Popes Creek, Westmoreland County, Virginia, the first child of Augustine Washington (landowner, part owner of an iron-works, and county justice of the peace) and Mary Ball Washington. At the age of 26, he married Martha Dandridge Custis on January 6, 1759. He fathered no children but raised two of Martha’s children from her previous marriage (John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis) and two step-grandchildren (George Washington Parke Custis and Eleanor Parke Custis) as his own. Washington died on December 14, 1799, at his home in Mount Vernon, Virginia, where he was buried.

Education

Attended local schools but received little formal education; farmed his father’s land; trained and worked as a surveyor.

Religion

Episcopalian

Political Affiliation

Unaffiliated

Highlights and Accomplishments

1749–1750: Surveyor of Culpeper County, Virginia

1753: Major, Southern District, Virginia miptia

1754: Lieutenant Colonel in the French and Indian Wars

1755–1758: Colonel and Commander, Virginia Forces

1758–1774: Member, Virginia House of Burgesses

1768–1774: Justice of the Peace, Fairfax County

1774: Delegate to the First Continental Congress

1775: Delegate to the Second Continental Congress

1775–1783: Commander of the Continental Army

1787: President of the Constitutional Convention

1789–1797: First President of the United States

George Washington was by all accounts “the indispensable man” of the American Founding.2 An early leader in Virginia’s resistance to British rule, he was the military commander who led a ragtag Continental Army to victory against the strongest and best trained military force in the world. Once the war was over, he resigned his military commission and returned to his home at Mount Vernon. Crucial to the success of the Constitutional Convention, his personal support of the new Constitution more than anything else assured its final approval. His election to the presidency—the office having been designed with him in mind—was essential to the establishment of the new nation.

The singular importance of Washington in the establishment of the American regime cannot be overstated. “[B]e assured,” James Monroe once reminded Thomas Jefferson, “his influence carried this government.”3

A soldier by profession and a surveyor by trade, Washington was first and foremost a man of action. He never learned a foreign language or traveled abroad nor wrote a political tract or a philosophical treatise on politics. Like Abraham Lincoln, Washington had received little formal education. And yet his words, thoughts, and deeds as a military commander, a President, and a patriotic leader make him one of the greatest statesmen—perhaps the greatest statesman—in our history.

The Life of Washington

Born in Virginia in 1732, as the descendant of English farmers, young Washington learned the surveying trade and traveled extensively in the area west of the Appalachian Mountains. At the age of 21, he was appointed a major in the Virginia militia. Later, as a lieutenant colonel, he was sent to the Ohio Valley to challenge a French expedition; the resulting skirmishes marked the opening battles of the French and Indian War (1754–1763).

After resigning from the British military, he served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to British Major General Edward Braddock. In 1755, he was appointed colonel and commander in chief of Virginia’s forces, which made him the highest-ranking American military officer, and for the next three years, he struggled with the endless problems of frontier defense.

From 1758 to 1774, he was a member of the House of Burgesses, the lower chamber of the Virginia legislature. In 1769, he introduced a series of resolutions (drafted by his colleague George Mason) denying the right of the British Parliament to tax the colonists, and in 1774, he introduced the Fairfax Resolves, which closed Virginia’s trade with Britain.

He was elected to the First Continental Congress and spent the winter of 1774 organizing militia companies in Virginia; he attended the Second Continental Congress in military uniform. In 1775, just after the battles of Lexington and Concord, he was appointed general and commander in chief of the Continental Army. For the next eight and a half years, Washington led the colonial army through the rigors of war, from the daring attack on Trenton from across the Delaware River to the trying times of Valley Forge and then the triumph of Yorktown in 1781. Through force of character and brilliant political leadership, Washington transformed an underfunded militia into a capable force that, although never able to take the British army head-on, outwitted and defeated the world’s mightiest military power.

After the War of Independence was won, Washington played a key role in the formation of the new nation. He was instrumental in bringing about the Constitutional Convention of 1787. A conference at Mount Vernon was the stimulus for Virginia to organize the Annapolis Convention of 1786, which in turn called for a convention in Philadelphia. Having been immediately and unanimously elected president of the Constitutional Convention, Washington worked actively throughout the proceedings to support the new Constitution, and an examination of his voting record shows his consistent support for a strong executive and clearly defined national powers. His widely publicized participation and endorsement gave the resulting document a credibility and legitimacy it would otherwise have lacked. The vast powers of the presidency, as one delegate to the Constitutional Convention wrote, would not have been made as great “had not many of the members cast their eyes towards General Washington as president; and shaped their ideas of the powers to be given to a president, by their opinions of his virtue.”4

As our first President, Washington set the precedents that define what it means to be a constitutional executive. He was a strong, energetic President but always aware of the limits on his office; he deferred to authority when appropriate but aggressively defended his prerogatives when necessary. His first term was dominated by the creation of the new government and the debate over Alexander Hamilton’s plan (which Washington supported) to build a national economy; his second was dominated by foreign affairs—mainly the French Revolution, a controversy which he wisely avoided, and the debate over his support of the Jay Treaty with Great Britain. Each of these events divided public opinion and contributed to the rise of the first political parties.

Washington wanted to retire after his first term, but the unanimous appeals of his colleagues induced him to serve again. Four years later—the situation stabilized, two important treaties concluded, and the republic strengthened—he finally decided to step down from the presidency, quit the political scene, and return to private life.

In 1796, on the anniversary of the Constitution, Washington released his Farewell Address, one of the greatest documents of the American political tradition. Best remembered for its counsel concerning international affairs, it also gives Washington’s advice concerning federal union and the Constitution, faction and political parties, the separation of powers, religion and morality, knowledge, and public credit.

During his lifetime, there was hardly a period when Washington was not in a position to bring his deep-seated ideas and the lessons of his experience to fruition, influencing not only events, but also, as his writings attest, the men around him. Four great themes of Washington’s life—individual character, religion and religious liberty, rule of law, and defense of national independence—are particularly reflective of the objectives of his statesmanship and suggest why his example is a prime model for today’s politics.

Character

That Washington is known for his character is no accident. One of his earliest writings was an adolescent copybook record of 110 “Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.” Drawn from an early etiquette book, these social maxims taught lessons of good manners concerning everything from how to treat one’s superiors (“In speaking to men of quality do not lean nor look them full in the face”) to how to moderate one’s own behavior (“Let your recreations be manful not sinful”).5 Simple rules of decent conduct, he always held, formed the backbone of good character.

In his later letters, Washington constantly warned young correspondents of “the necessity of paying due attention to the moral virtues” and avoiding the “scenes of vice and dissipation” often presented to youth.6 Because an early and proper education in both manners and morals would form the leading traits of one’s life, he constantly urged the development of good habits and the unremitting practice of moral virtue. “To point out the importance of circumspection in your conduct, it may be proper to observe that a good moral character is the first essential in a man, and that the habits contracted at your age are generally indelible, and your conduct here may stamp your character through life,” he advised one correspondent. “It is therefore highly important that you should endeavor not only to be learned but virtuous.”7

Washington’s own moral sense was the compass of both his private life and his public life, having become for him a “second” nature. The accumulation of the habits and dispositions, both good and bad, that one acquired over time defined one’s character. In the 18th century, “character” was also shorthand for the persona for which one was known and was tied to one’s public reputation. Washington knew that the best way to establish a good reputation was to be, in fact, a good man. “I hope I shall always possess firmness and virtue enough to maintain (what I consider the most enviable of all titles) the character of an honest man,” he told Hamilton, “as well as prove (what I desire to be considered in reality) that I am.”8

Republican government, far from being unconcerned about questions of virtue and character, was understood by Washington to require self-government. In his First Inaugural, Washington spoke of “the talents, the rectitude, and the patriotism, which adorn the characters selected to devise and adopt” the law. It was here, and not in the institutional arrangements or laws themselves, that Washington ultimately saw the “surest pledges” of wise policy and the guarantee that “the foundation of our national policy, will be laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality.”9

Religion and Religious Liberty

Religion and morality are the most important sources of character, Washington advised, as they teach men their moral obligations and create the conditions for decent politics. They are necessary for the maintenance of public justice. A sense of individual religious obligation, Washington noted in his Farewell Address, is needed to support the oaths necessary in courts of law. But it goes beyond that: “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men & citizens.”10

This holds true despite the theories of academic elites, then or now, who argue that religion is not required to support the morality needed for free government. “And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion.”11 Washington conceded some ground to rationalists—like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson—who seem to have had less personal use for religion but nevertheless insisted on the general argument. “No matter what might be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”12 While there might be particular cases where morality did not depend on religion, this was not the case for the morality of the nation.

Washington’s statements about the importance of religion in politics must be understood in light of his equally strong defense of religious liberty. In a letter to the United Baptists, for instance, he wrote that he would be a zealous guardian against “spiritual tyranny, and every species of religious persecution,” and that under the federal Constitution every American would be protected in “worshiping the Deity according to the dictates of his own conscience.”13

Perhaps Washington’s most eloquent statement is found in his letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island:

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.14

While it is often thought that the separation of church and state marks the divorce of religion and politics in America, Washington’s conception of religious liberty was almost exactly the opposite. His understanding of free government requires the moralization of politics, which includes—and requires—the expansion of religious influence in American politics. For Washington, religious liberty meant that religion, in the form of morality and the moral teachings of religion, was now free to exercise an unprecedented influence over private and public opinion by shaping mores, cultivating virtues, and in general providing an independent source of moral reasoning and authority.

The Rule of Law

Washington led a revolution to root out monarchical rule in America and establish a republican government based on the rule of law. In 1776 and again in 1777, when Congress was forced to abandon Philadelphia in the face of advancing British troops, General Washington was granted dictatorial powers to maintain the war effort and preserve civil society; he gave the authority back as soon as possible. At the end of the war, at the moment of military triumph, one of his colonels raised the possibility of making Washington an American king—a proposal he immediately repudiated. Washington also rejected the option of using military force (with or without his participation) to take control of Congress and force upon it a new national administration. Instead, when the task assigned him was complete, General Washington resigned his military commission and returned to private life.

Americans take for granted the peaceful transfer of power from one President to another, but it was Washington’s relinquishing of power in favor of the rule of law—a first in the annals of modern history—that made those transitions possible. “The moderation and virtue of a single character,” Thomas Jefferson tellingly noted, “probably prevented this Revolution from being closed, as most others have been, by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish.”15 His peaceful transfer of the presidency to John Adams in 1797 inaugurated one of America’s greatest democratic traditions. King George III wrote that Washington’s retirement, combined with his resignation 14 years earlier, “placed him in a light the most distinguished of any living man” and made him “the greatest character of the age.”16

George Washington was a strong supporter of the Constitution. It established a limited but strong national government, created an energetic executive, and formed the legal framework necessary for a commercial republic. By the Constitution, the U.S. government is limited and structured to prevent encroachment, with “as much vigour as is consistent with the perfect security of Liberty” yet strong enough “to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.” As a result, it is the greatest check against tyranny and the best guardian of American freedoms. Washington reminded his fellow citizens that the Constitution deserves support and fidelity. Until it was formally changed “by an explicit and authentic act of the whole People,” he wrote, the Constitution is “sacredly obligatory upon all.”17

Ignoring the Constitution and allowing the rule of law to be weakened, Washington sternly warned, is done at the nation’s own peril. The American people must always guard against “irregular oppositions” to legitimate authority and “the spirit of innovation” that desires to circumvent the principles of the Constitution. Nor should Americans overlook Washington’s abiding concern about the corrupting power of the state. He warned that government tends to encroach on freedom and consolidate power: “A just estimate of that love of power, and proneness to abuse it, which predominates in the human heart is sufficient to satisfy us of the truth of this position.” In the long run, disregard for the rule of law allows “cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men” to subvert the people and take power illegitimately by force or fraud. This, he reminded his fellow citizens, is “the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed.”18

National Independence

In the most quoted—and misinterpreted—passage of his Farewell Address, Washington warned against excessive ties with any country: “’Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent Alliances, with any portion of the foreign world.” He recommended as the great rule of conduct that the United States primarily pursue commercial relations with other nations and have “as little political connection [with them] as possible.”19

Although this statement is often cited to support isolationism, it is difficult to construe Washington’s words as strict noninvolvement in the political and military affairs of the world. The activities of his Administration suggest no such policy; the warning against “entangling alliances,” often attributed to Washington, is found in the 1801 Inaugural Address of Thomas Jefferson.20 President Washington warned against political connections and permanent alliances with other nations, but he also added a hedge: “So far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do.” In order to maintain a strong defensive posture, the nation could depend on “temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.”21

The predominant motive of all of Washington’s policies, both foreign and domestic, was to see America “settle and mature its yet recent institutions” so as to build the political, economic, and physical strength—and the international standing—necessary to give the nation “the command of its own fortunes.”22 Rather than a passive condition of detachment, Washington described an active policy of national independence as necessary for America at some not too distant point in the future to determine its own fate.

Commerce, not conquest or subservience, was to be the primary means by which America would acquire goods and deal with the world. Commercial policy should be impartial, neither seeking nor granting favors or preferences, and flexible, changing from time to time as experience and circumstances dictate. But even under the best circumstances, economic and trade policy should be conducted in ways that maintain American independence.

Washington’s intent was to establish a strong, self-determined, and independent foreign policy, but this idea also encompasses a sense of moral purpose and well-being—sovereignty in the fullest and most complete sense. For America, this means a free people governing themselves, establishing their own laws, and setting up a government they think will best ensure their safety and happiness. Or, as the Declaration of Independence says: “to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God entitle them” and obtain the full power to do the “Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.”

In the end, to have the command of its own fortunes means that America has the full use of its independence—not to impose its will on other nations, but to prove without help or hindrance from other nations the viability of republican government. Washington’s wish, as explained to Patrick Henry, was that the United States be “independent of all, and under the influence of none. In a word, I want an American character, that the powers of Europe may be convinced we act for ourselves and not for others. This in my judgment, is the only way to be respected abroad and happy at home.”23

First in War, First in Peace

The last journeys of Washington’s life were to the army camp at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), and to Philadelphia to consult on military matters. That same year, President John Adams appointed Washington head of a provisional army during a period of tensions with France. But Washington was happily retired at his beloved home, Mount Vernon. A sore throat, the result of inspecting his farm during a snowstorm, quickly worsened, and he died on December 14, 1799.

The news of Washington’s death spread quickly throughout the young nation. Every major city and most towns conducted official observances. Churches held services to commemorate his life and role in the American Revolution. Innumerable pronouncements, speeches, and sermons were delivered to lament the event. From the date of his death until his birthday in 1800, some 300 eulogies were published throughout the United States from as far north as Maine and as far south as Georgia to as far west as Natchez on the Mississippi River.

Congressman Henry Lee III delivered the official eulogy. Although we remember only a few phrases today, it included these memorable words:

First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen, he was second to none in humble and enduring scenes of private life. Pious, just, humane, temperate, and sincere; uniform, dignified, and commanding, his example was as edifying to all around him as were the effects of that example lasting. Correct throughout, vice shuddered in his presence and virtue always felt his fostering hand. The purity of his private character gave effulgence to his public virtues.24

“Let his countrymen consecrate the memory of the heroic general, the patriotic statesman and the virtuous sage,” read the official message of the United States Senate. “Let them teach their children never to forget that the fruit of his labors and his example are their inheritance.”25

President John Adams was more to the point: “His example is now complete, and it will teach wisdom and virtue to magistrates, citizens, and men, not only in the present age, but in future generations, as long as our history shall be read.”26

Selected Primary Writing

Farewell Address (September 19, 1796)27

Friends & Fellow-Citizens

…Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the attachment.

The Unity of Government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so, for it is a main Pillar in the Edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that, from different causes & from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly & insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union to your collective & individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual & immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the Palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our Country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

For this you have every inducement of sympathy and interest. Citizens by birth or choice, of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of AMERICAN, which belongs to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same Religion, Manners, Habits & political Principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together—the independence and Liberty you possess are the work of joint councils, and joint efforts—of common dangers, sufferings and successes.

…To the efficacy and permanency of Your Union, a Government for the whole is indispensable. No Alliances however strict between the parts can be an adequate substitute. They must inevitably experience the infractions & interruptions which all Alliances in all times have experienced. Sensible of this momentous truth, you have improved upon your first essay, by the adoption of a Constitution of Government better calculated than your former for an intimate Union, and for the efficacious management of your common concerns. This government, the offspring of our own choice, uninfluenced and unawed, adopted upon full investigation and mature deliberation, completely free in its principles, in the distribution of its powers, uniting security with energy, and containing within itself a provision for its own amendment, has a just claim to your confidence and your support. Respect for its authority, compliance with its Laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true Liberty. The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their Constitutions of Government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, ’till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole People, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the People to establish Government presupposes the duty of every Individual to obey the established Government.

All obstructions to the execution of the Laws, all combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control[,] counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the Constituted authorities, are distructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force—to put in the place of the delegated will of the Nation, the will of a party; often a small but artful and enterprizing minority of the Community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the Mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the Organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common counsels and modified by mutual interests. However combinations or Associations of the above description may now & then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the Power of the People, & to usurp for themselves the reins of Government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

Towards the preservation of your Government and the permanency of your present happy state, it is requisite, not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority, but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles however specious the pretexts. One method of assault may be to effect, in the forms of the Constitution, alterations which will impair the energy of the system, and thus to undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In all the changes to which you may be invited, remember that time and habit are at least as necessary to fix the true character of Governments as of other human institutions—that experience is the surest standard, by which to test the real tendency of the existing Constitution of a country—that facility in changes upon the credit of mere hypothesis & opinion, exposes to perpetual change, from the endless variety of hypothesis and opinion: and remember, especially, that for the efficient management of your common interests, in a country so extensive as ours, a Government of as much vigour as is consistent with the perfect security of Liberty is indispensable—Liberty itself will find in such a Government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest Guardian. It is indeed little else than a name, where the Government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the Society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.

I have already intimated to you the danger of Parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on Geographical discriminations. Let me now take a more comprehensive view, & warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the Spirit of Party, generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human Mind. It exists under different shapes in all Governments, more or less stifled, controuled, or repressed; but, in those of the popular form, it is seen in its greatest rankness and is truly their worst enemy.

…There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the Administration of the Government and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true—and in Governments of a Monarchical cast, Patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favour, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in Governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency, it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose. And there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be, by force of public opinion, to mitigate & assuage it. A fire not to be quenched; it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming it should consume.

It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free Country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective Constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the Powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create whatever the form of government, a real despotism. A just estimate of that love of power, and proneness to abuse it, which predominates in the human heart is sufficient to satisfy us of the truth of this position. The necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power, by dividing and distributing it into different depositaries, & constituting each the Guardian of the Public Weal against invasions by the others, has been evinced by experiments ancient and modern; some of them in our country & under our own eyes. To preserve them must be as necessary as to institute them. If in the opinion of the People, the distribution or modification of the Constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit which the use can at any time yield.

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men & citizens. The mere Politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect & to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private & public felicity. Let it simply be asked where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths, which are the instruments of investigation in Courts of Justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure—reason & experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

’Tis substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule, indeed, extends with more or less force to every species of free Government. Who that is a sincere friend to it can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric?

Promote then, as an object of primary importance, Institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

…Observe good faith & justice tow[ar]ds all Nations[;] cultivate peace & harmony with all. Religion & morality enjoin this conduct; and can it be that good policy does not equally enjoin it? It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and at no distant period, a great Nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a People always guided by an exalted justice & benevolence. Who can doubt that in the course of time and things the fruits of such a plan would richly repay any temporary advantages w[hi]ch might be lost by a steady adherence to it? Can it be. that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a Nation with its virtue? The experiment, at least, is recommended by every sentiment which ennobles human Nature. Alas! is it rendered impossible by its vices?

In the execution of such a plan, nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular Nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded; and that, in place of them, just & amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The Nation, which indulges towards another a habitual hatred, or a habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. Antipathy in one Nation against another disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable, when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur. Hence frequent collisions, obstinate envenomed and bloody contests. The Nation, prompted by ill will & resentment, sometimes impels to War the Government, contrary to the best calculations of policy. The Government sometimes participates in the national propensity, and adopts through passion what reason would reject; at other times it makes the animosity of the nation subservient to projects of hostility instigated by pride, ambition and other sinister & pernicious motives. The peace often, sometimes perhaps the Liberty, of Nations has been the victim.

So likewise, a passionate attachment of one Nation for another produces a variety of evils. Sympathy for the favorite nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest, in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels & Wars of the latter, without adequate inducement or justification: It leads also to concessions to the favourite Nation of priviledges denied to others which is apt doubly to injure the Nation making the concessions—by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained—& by exciting jealousy, ill will, and a disposition to retaliate, in the parties from whom eq[ua]l priviledges are withheld: And it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favourite Nation), facility to betray, or sacrifice the interests of their own country, without odium, sometimes even with popularity; gilding with the appearances of a virtuous sense of obligation a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good, the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption, or infatuation.

As avenues to foreign influence in innumerable ways, such attachments are particularly alarming to the truly enlightened and independent Patriot. How many opportunities do they afford to tamper with domestic factions, to practice the arts of seduction, to mislead public opinion, to influence or awe the public Councils! Such an attachment of a small or weak, towards a great & powerful Nation dooms the former to be the satellite of the latter.

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake; since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of Republican Government. But that jealousy to be useful must be impartial; else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defence against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another, cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real Patriots, who may resist the intrigues of the favourite, are liable to become suspected and odious; while its tools and dupes usurp the applause & confidence of the people, to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign Nations is in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.

Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence therefore it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations & collisions of her friendships, or enmities.

Our detached & distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one People, under an efficient government, the period is not far off, when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or War, as our interest guided by justice shall counsel.

Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, Rivalship, Interest, Humour or Caprice?

’Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent Alliances, with any portion of the foreign world—So far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it—for let me not be understood as capable of patronising infidility to existing engagements. (I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy.) I repeat it, therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But in my opinion, it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Taking care always to keep ourselves, by suitable establishments, on a respectable defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.

Harmony, liberal intercourse with all Nations, are recommended by policy, humanity and interest. But even our Commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand: neither seeking nor granting exclusive favours or preferences; consulting the natural course of things; diffusing & diversifying by gentle means the streams of Commerce, but forcing nothing; establishing with Powers so disposed—in order to give trade a stable course, to define the rights of our merchants, and to enable the Government to support them—conventional rules of intercourse, the best that present circumstances and mutual opinion will permit, but temporary, & liable to be from time to time abandoned or varied, as experience and circumstances shall dictate; constantly keeping in view; that ’tis folly in one Nation to look for disinterested favours from another—that it must pay with a portion of its Independence for whatever it may accept under that character—that, by such acceptance, it may place itself in the condition of having given equivalents for nominal favours and yet of being reproached with ingratitude for not giving more. There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favours from Nation to Nation. ’Tis an illusion which experience must cure, which a just pride ought to discard.

In offering to you, my Countrymen, these counsels of an old and affectionate friend, I dare not hope they will make the strong and lasting impression, I could wish—that they will controul the usual current of the passions, or prevent our Nation from running the course which has hitherto marked the Destiny of Nations: But, if I may even flatter myself that they may be productive of some partial benefit, some occasional good, that they may now & then recur to moderate the fury of party spirit, to warn against the mischiefs of foreign Intriegue, to guard against the Impostures of pretended patriotism—this hope will be a full recompence for the solicitude for your welfare, by which they have been dictated.

…With me, a predominant motive has been to endeavour to gain time to our country to settle & mature its yet recent institutions, and to progress without interruption, to that degree of strength & consistency which is necessary to give it, humanly speaking, the command of its own fortunes.

Though, in reviewing the incidents of my Administration, I am unconscious of intentional error—I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope that my Country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that after forty five years of my life dedicated to its Service, with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.

Relying on its kindness in this as in other things, and actuated by that fervent love towards it, which is so natural to a man, who views in it the native soil of himself and his progenitors for several Generations; I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat, in which I promise myself to realize, without alloy, the sweet enjoyment of partaking, in the midst of my fellow Citizens, the benign influence of good Laws under a free Government—the ever favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers.

Recommended Readings

- James Thomas Flexner, Washington: The Indispensable Man (New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1984).

- Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father: Rediscovering George Washington (New York: Free Press, 1996).

- Matthew Spalding and Patrick Garrity, A Sacred Union of Citizens: George Washington’s Farewell Address and the American Character (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997).

- Glenn Phelps, George Washington and American Constitutionalism (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1994).

- Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin Press, 2010).

Notes

[1] Major General Henry Lee, “A Funeral Oration in Honour of the Memory of George Washington, 26 December 1799” (Brooklyn, NY: Thomas Kirk, 1800), pp. 14–15.

[2] James Thomas Flexner, Washington: The Indispensable Man (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1984), p. vii.

[3] “To Thomas Jefferson from James Monroe, 12 July 1788,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-13-02-0256 (accessed May 14, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[4] “Pierce Butler to Weeden Butler, Mary-Ville [South Carolina], 5 May [1788],” in The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, ed. John P. Kaminski et al. (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1995), Vol. 17, pp. 381–385, https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ATR2WPX6L3UFLH8I (accessed May 14, 2025).

[5] George Washington, “The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation,” Rules 37 and 109, in George Washington: A Collection, comp. and ed. W. B. Allen (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1988), pp. 8 and 13, https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/848/0026_Bk.pdf (accessed May 15, 2025).

[6] “From George Washington to George Steptoe Washington, 23 March 1789,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0334 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[7] “From George Washington to George Steptoe Washington, 5 December 1790,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-07-02-0017 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[8] “From George Washington to Alexander Hamilton, 28 August 1788,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-06-02-0432 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[9] George Washington, “First Inaugural Address: Final Version, 30 April 1789,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0130-0003 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[10] George Washington, “Farewell Address, 19 September 1796,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-20-02-0440-0002 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “From George Washington to the United Baptist Churches of Virginia, May 1789,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0309 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[14] “From George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, 18 August 1790,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-06-02-0135 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[15] “To George Washington from Thomas Jefferson, 16 April 1784,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0215 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[16] King George III, quoted in Rufus King, memorandum, May 3, 1797, in The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King: Comprising his Letters, Private and Official, His Public Documents, and His Speeches, Vol. III, ed. Charles R. King (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896), p. 545, https://dn790001.ca.archive.org/0/items/rufuskinglife03kingrich/rufuskinglife03kingrich.pdf (accessed May 15, 2025).

[17] Washington, “Farewell Address.”

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Thomas Jefferson, “First Inaugural Address, 4 March 1801,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-33-02-0116-0004 (accessed May 15, 2025).

[21] Washington, “Farewell Address.”

[22] Ibid.

[23] “From George Washington to Patrick Henry, 9 October 1795,” National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-19-02-0024 (accessed May 15, 2025). Emphasis in original.

[24] Lee, “Funeral Oration in Honour of the Memory of George Washington,” pp. 14–15.

[25] Samuel Livermore, President Pro Tempore, U.S. Senate, draft of Senate message to President John Adams on the death of George Washington, in Journal of the Senate of the United States, 6th Congress, 1st Session, December 23, 1799, p. 12, https://www.congress.gov/senate-journal/congress-6-session-1.pdf (accessed May 15, 2025).

[26] John Adams, message to the Senate in response to Senate message on the death of George Washington, December 23, 1799, in ibid., pp. 12–13.

[27] See note 10, supra. Emphasis in original.